World equities – increased risk and return

This chapter is about the main return-generating portion of your rational portfolio, equities. In the chapter I hope to convince you that the only equity exposure you need is one that represents the broadest and cheapest exposure possible; an exposure to a world equity index.

Only buy world equity index trackers

In order to move the portfolio towards the promise of higher returns you need to increase your risk/return profile by buying publicly listed equities. I am not suggesting you buy equities because I have some insight that equities are set to have an outstanding performance relative to other assets. It is because I consider equities to be the highest expected return asset class (at the highest risk) that I think someone without an edge should invest in. But the question is: which equities?

Figure 5.1 is a chart of the Dow Jones, the world’s oldest stock market index that was created to track the US stock market since its inception in 1896. From a start of around 40 in 1896 that index is trading at around 20,000 today.

As I will discuss further in the next chapter, far from all equity markets have been as successful as the Dow and we can’t extrapolate the Dow performance to the wider world. When estimating the return we can expect from investing in equities it is important to incorporate the returns of all equity markets, also the ones that have done badly. That said, it is also clear that investments in equities have been the source of incredible wealth creation for many investors over the past couple of centuries, and remains the major source of prospective investment returns for investors all over the world.

From the perspective of the rational investor, each dollar invested in the markets around the world is presumed equally smart. This means that we should own the shares in the market according to their fraction of the market’s overall value. So if we assume that the market refers only to the US stock market and that Apple shares represented 3% of the overall value, then 3% of our equity holdings should be Apple shares. If we do anything other than this, we are somehow saying that we are more clever, more informed – that we have an edge on the market.

But why stop at the US market? If there is $25 trillion invested in the US stock market and $4 trillion in the UK market there is no reason to think that the UK market is any less informed or efficient than the US one. And likewise with any other market in the world that investors have access to. We should invest with them all, in the proportions of their share of the world equity markets within the bounds of practicality.

Many investors overweigh ‘home’ equities. The UK represents less than 3% of the world equity markets, but the proportion of UK equities in a UK portfolio is often 35–40%. Investors feel they know and understand their home market. Perhaps they think they are able to spot opportunities before the wider market, although in fairness the concentration is often because of investment restrictions or because investors are matching liabilities connected to the local market. Various studies suggest that this ‘home field advantage’ is perceived rather than real, but we continue to have our portfolios dominated by our home market.

If you over- or underweight one country compared to its fraction of the world equity markets you would effectively be saying that a dollar invested in an underweight country is less clever/informed than a dollar invested in the country that you allocate more to. You would essentially claim to see an advantage from allocating differently from how the multi-trillion dollar international financial markets have allocated which you are not in a position to do unless you have an edge.

Consider the following two portfolios: one consists of the world equity portfolio as the global financial market have allocated values to the various countries underlying companies, and the other your portfolio which is allocated differently.

What you immediately spot is that implicit in your portfolio are a bunch of statements that are actually incredibly bold. You have allocated far more of your portfolio to the UK than the financial markets have, which only makes sense if you think the UK market is undervalued and due to outperform the global equity market. Likewise, you think the US and Japanese markets will fare relatively poorly (or you would not have under-allocated to them), India undervalued, etc. You basically claim to know better than the global financial markets, which we earlier discussed not only requires amazing skill and insight, but is also a very expensive way to manage your money.

So besides it being much simpler and cheaper, since investors have already moved capital between various international markets efficiently, the international equity portfolio is the best one.

A major point of this book: A world equity index tracker is the only equity investment a rational investor ever needs to own. Please remember and act on that!

Take my situation as an example. As a Danish citizen who has lived in the US and UK for over 20 years I might instinctively be over-allocating to Europe and the US because I’m familiar with those markets. But in doing that I would implicitly be claiming that Europe and the US would have a better risk/return profile than the rest of the world. This might or might not turn out that way, but the point is that we don’t know ahead of time. Or you could find yourself making statements like, ‘I believe the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries are set to dominate growth over the next decades and are cheap.’ Perhaps you’d be right, but you would also be saying that you know something that the rest of the world has not yet discovered. This does not make sense unless you have an edge.

If you are interested, visit www.kroijer.com for a short video discussing the merits of the world equity index trackers.

The advantage of diversification

The world equity portfolio is the most diversified equity portfolio we can find. To give an idea of the benefits of diversification in the home market consider Figure 5.2, which suggests the benefits decline as we add securities in the home market. This makes sense. Stocks trading in the same market will tend to correlate greatly (they are exposed to the same economy, legal system, etc.), and after picking a relatively small number of them you have diversified away a great deal of the market risk of any individual stock. So you could actually gain a lot of the advantages from the US index funds by picking 15–20 large capitalisation stocks and sticking with them, assuming they did not all act like one. (If you only added stocks from one sector that all moved in the same way the diversification benefits would be far lower.) It is not the rational US portfolio that you have achieved (you claimed an edge by selecting a subset of 15–20 stocks and deselecting the rest of the market), but from a diversification perspective you have accomplished a lot.

By expanding the portfolio beyond the home market we achieve much greater diversification in our investments. This is because we spread our investments over a larger number of stocks but, more importantly, because those stocks are based in different geographical areas and local economies. Decades ago we didn’t really have the opportunity to invest easily across the world, and while it’s still not seamless for investors in many places, investing abroad in a geographically diversified way is a lot easier than it used to be.

So, in summary, the key benefits of a broad market-weighted portfolio are as follows:

- The portfolio is as diversified as possible and each dollar invested in the market is presumed equally clever, consistent with what a rational investor believes. (I bet a lot of Japanese investors wished they had diversified geographically after their domestic market declined 75% from its peak over the past 20 years.)

- Since we are simply buying ‘the market’ as broadly as we can it’s a very simple portfolio to construct and thus very cheap. We don’t have to pay anyone to be smart about beating the market. Over time the cost benefit can make a huge difference. Don’t ignore that.

- This kind of broad-based portfolio is now available to most investors whereas only a couple of decades ago it was not. Most people then thought ‘the market’ meant only their domestic market, or at best a regional market. Take advantage of this development to buy broader-based products.

If for whatever reason you are unable to buy a broad geographic portfolio like the one described above, then buy as broad a geographic portfolio as you can and get as large a fraction of the market as you can. So if you can only buy US stocks, buy the whole market – like a Wilshire 5000 tracker instead of an S&P 500 tracker – if the costs are the same. If you can only buy European stocks, buy that whole market, etc.

Do alternative weightings do better?

Many works on investing suggest that value investments (shares with low price/book or price/earnings ratios) and smaller companies both outperform the general market over time. Various indices and products have been created to cater to this argument.

In short, I don’t think rational investors should buy alternative weighted investments as proxies for their market exposure. By actively de-selecting a portion of the market (the higher growth or larger companies) investors are claiming that others who have invested in those companies are somehow less informed than themselves, which is a grand statement and inconsistent with rational investing. It is probably fair to assume that all those investors in the growth or larger companies are highly experienced and informed, have read all the relevant books on investing and are well aware of all the aspects of historical outperformance of various sectors of the markets. They are not stupid; in fact they are as much a part of the market as the value or smaller company investors are. Do you really think that the trillions of dollars that follow companies like Google and Apple are somehow from ill-informed investors and that you know more about the markets than they do to the extent that you can de-select those stocks?

Anyone who suggests an alternative weighting to that of the overall market looks more like an active investor than a passive one. Likewise, the implicit cost of the part of the portfolio that diverges from the general index can easily approach the fee levels of an actively managed fund. Suppose an alternative weighted index has an overlap of 66% with the wider market, but costs 0.3% more a year to implement. In that case you are paying 1% a year on the part of your investment that is different from the general market, or fees akin to those demanded by some active managers.

I also think that many of these alternative weighted indices are created to match what has had the best historical performance and thus be easier to sell. If stocks with high price/earnings (P/E) and growth rates had been the best performers over the past decades many alternative weighted indices would consist of that market segment, complete with charts outlining the great reasons why that trend could be expected to continue. We would be guilty of fitting the product to past returns and essentially saying that we had the insight that the future would be like the past.

On top of the active de-selection of some parts of the market that it implies, my main issue with small company investing has to do with implementation. Actively implementing a portfolio of smaller companies is very expensive as the execution trade is subject to large bid/offer spreads and price movements if you trade in any size. But even if you could pass the hurdle of costs, you are still left with the same question: do you really know enough about the markets to claim an edge to the extent that you over-weigh these stocks at the expense of other stocks in the market? What is it you know that the wider market doesn’t?

Whether you are picking a North American Biotech index, the Belgian index, an index of commodities stocks, etc. you are essentially claiming an edge and advantage in the market as if you were picking Microsoft shares to outperform.

To ensure that this book is not without a ‘get rich quick’ scheme, here is one. Buy whatever index you think is sure to outperform and sell short the broader index against it with as much money as you can borrow. Now wait for the world to prove you right, ensure you riches and the financial media to turn up and write articles about your investing brilliance.

In summary: stick with the broadest and cheapest market.

What are world equities?

Today, the total value of the equity markets in the world is $75–80 trillion. As you would expect, this value has grown dramatically over the past decades, rendering what seemed like massive drawdowns in 2008–09 appear as minor blips on what looks like a certain upward trajectory.

The increase in the size of the world market capitalisation is not only because share prices went up. Many new shares were listed on the stock exchanges and particularly outside the US and Europe new markets took off in spectacular fashion. There was also an increase in population, an increase in GDP and savings, privatisations of state-owned enterprises, and more countries moving from planned to market economies, all of which contributed to the large rise.1

The US is, by some distance, the largest equity market in the world. The market value of the shares listed in the US is approximately $25 trillion, with Apple and Google as the two most valuable companies at the time of writing. Although the US stocks represent the largest country fraction of world equities this share is smaller than it was even a decade ago as rising emerging markets have come to represent an ever-greater share of world equities.

Market capitalisation data changes continuously, so in looking at the split of current market values for the various countries in the world (see Figure 5.3) bear in mind this could have changed significantly since publication.

While different world indices include country exposures in slightly different ways Figure 5.3 shows roughly the exposure you would have if you buy a product that tracks world equities. Since some ‘world’ indices do not include all the countries with functioning equity markets, the weightings of those that are included are slightly higher. But keep in mind that even if your index tracker only includes the top 35–40 countries, that will still represent will well over 95% of the total world equity valuation and be a plenty fine representation. The list of markets and weightings should be available on the website of any product provider you are considering.

A criticism of many world equity investment products is the overrepresentation of US equities, mainly due to free float, liquidity or poor access to trade securities in other markets. While I agree it isn’t always great, I think the issue is somewhat alleviated by the large non-US business exposure of the largest US companies such as Apple, Google, Microsoft, etc. Also, it is a fair assumption that over time more countries have better access to foreign investors, IPO large previously non-quoted companies, larger free float, and thus become a larger part of the global indices that the product providers try to replicate.

Figure 5.4 Equity market value versus country GDP

Based on data from www.worldbank.org and www.imf.org

It is worth noting that various countries have greater or smaller stock markets relative to their national economies (see Figure 5.4). The US currently represents approximately 35% of world equity markets, but its share of the world GDP is only around 20% (and declining). Some countries have a longer history of stock listings and perhaps a more favourable legal system for publicly quoted stocks. Likewise, because most companies today have significant operations abroad we should not expect the stock market valuation to be a precise reflection of the domestic economy. But whatever the reasons, as a world equity investor you should not expect your geographic exposure to exactly match that of economic output.

While I think it would be ideal if all countries had roughly similar GDP/market value ratios, as then the portfolio would be even better diversified, I think it is more important to be weighted in line with market values in a world index. If there are risk/return benefits from reallocating capital between markets we can trust the efficient markets to do so, and as a result trust our market value-based portfolio to be efficient.

When you buy a world equity product you will naturally incur foreign exchange exposure as the majority of the underlying securities will be listed in a currency other than your own. For example, when you as a UK-based investor buy the sterling-denominated world equity index tracker you will indirectly be buying shares in the Brazilian oil company Petrobras. Petrobras is quoted in the Brazilian currency (the real (R)) so in order to buy the Petrobras shares, the product provider has to take the sterling amount and exchange it for reals, and then buy the stock (see Figure 5.5). Likewise with all the other currencies and securities represented in the index.2

In the example shown in Figure 5.5 you are now exposed both to the fluctuation in the share price of Petrobras and also movements in the GBP/Real exchange rate (see Figure 5.6 for an example).

In this example, I assumed that the Petrobras share price went from R20 to R25 while the £/R rate went from 3.2 to 3.1. The aggregate impact of this on the portfolio was that the £100 investment went up in value to £129 because of the mix of share price appreciation and the £/R currency movement.

The many different stocks and currency exposures in the world equity portfolio add further to the diversification benefits of the broad-based portfolio exposure. If your base/home currency devalued or performed poorly, the diversification of your currency exposure would serve to protect your downside.

Some investment advisers argue that you should invest in assets in the same currency that you will eventually need the money in. So a UK investor should buy UK stocks, a Danish investor should buy Danish stocks, someone who eventually needs money in different currencies should buy a mix (if you have different costs in different currencies), etc. There is some merit in currency matching specific and perhaps shorter-term liabilities, but the matching is better done by purchasing government bonds in your home currency (the minimal risk asset). If you worry that major currencies fluctuate too much for you, I question whether you should be taking equity market risk in the first place.

The broader investment and currency exposure is favourable not only from a diversifying perspective, but also as protection against bad things happening in your home country. Historically, whenever a currency has been an outlier it has performed poorly because of problems in that country (there are exceptions to this rule of thumb), and it is exactly in those cases that the protection of a diversified geographic exposure is of the greatest benefit to you.3

Expected returns: no promises, but expect 4–5% after inflation

The return expectation from equity markets is driven by our view of the ‘equity risk premium’. The equity risk premium is a measure of how much extra the market expects to get paid for the additional risk associated with investing in equity markets over the minimal risk asset. This does not mean that stock markets will be particularly poor or attractive right now; it means that investors historically have demanded a premium for investing in risky equities, as opposed to less-riskier assets. We also assume that investors expect to be paid a similar premium for investing in equities over safe government bonds in future as they have historically.

The size of the equity risk premium is subject to much debate, but numbers in the order of 4–5% are often quoted. If you study the returns of the world equity markets over the past 100 years (see Table 5.1) the annual compounding rate of return for this period is close to this range. Of course it is impossible to know if the markets over that period have been particularly attractive or poor for equity holders compared to what the future has in store.

The equity risk premium is not a law of nature, but simply an expectation of future returns, in this case based on what those markets achieved in the past, including the significant drawdowns that occurred. Economists and finance experts disagree strongly on what you should expect from equity returns in future and some consider this kind of ‘projecting by looking in the rear-view mirror’ wrong. In my view, the long history and volatility of equity market returns gives a good idea of the kind of returns we can expect in future. Equity market investors have in the past demanded a 4–5% return premium for the risks that equity markets entail, and I think there is a good probability that investors in future are going to demand a similar kind of return premium for a similar kind of risk in the equity markets.

Table 5.1 Returns 1900–2015 (%)

Source: Credit Suisse Global Returns Handbook 2016

A criticism of using historical returns to predict future returns is that this predicts higher returns at market peaks and lower returns at market lows.4 Historical returns looked a lot better on 1 July 2008 than on 1 July 2009 (after the crash), and perhaps because you were attracted by the high historical returns in mid–2008 this was exactly the time that you invested in equities. Combining high historical returns with low expected risk at the time made equity markets look very attractive at precisely the wrong moment.

I understand why some criticise the expected return, but think that the length of data mitigates this. With hundreds of years of data across many countries (some have used only US data in the past, but that introduces selection bias by excluding markets that have performed poorly), incorporating great spectacular declines, great rises and everything in between, I think historical data is the best guide to the kind of risk and return we can expect from equity markets in future.

Practically speaking, historically investors were simply unable to buy a world equity index tracker. One of the leading index providers, MSCI, only started tracking a ‘world index’ in late 1960s, but finding liquid products that actually followed this or similar indices did not start in earnest until decades after that. Figure 5.7 shows historical returns for the MSCI World Index since inception. In this case, I think the time horizon is too short (40+ years) to use the data to make predictions about future world equity returns, when we have longer historical data sets (albeit not as an index done at the time).

Lars’s predictions

So, in simple terms, on average I expect to make a 4–5% return a year above the minimal risk rate5 in a broad-based world equity portfolio. This is not to suggest that I expect this return to materialise every year, but rather that if I had to make a guess on the compounding annual rate in future it would be 4–5% (see Table 5.2). Note that while the equity premium here is compared to short-term US bonds I would expect the same premium to other minimal risk currency government bonds because the real return expectation of short-term US government bonds is roughly similar to that of other AAA/AA countries like the UK, Germany, Japan, etc.

Table 5.2 Expected future returns (including returns from dividends) (%)

| Real1 | Risk2 | |

| World equities | 4.5–5.5 | High |

| Minimal risk asset | 0.50 | Very low |

| Equity risk premium | 4–5 |

1After inflation.

2See Chapter 6 for a discussion of issues with risk measures.

For those who consider these expected returns disappointing, I’m sorry. Writing higher numbers in a book or spreadsheet won’t make it true. Some would even suggest that expecting equity markets to be as favourable in the future as in the past is wishful thinking. Besides, a 4–5% annual return premium to the minimal risk asset will quickly add up to a lot; you would expect to double your money in real terms roughly every 15 years!

The power of compounding never ceases to amaze me. If I dropped my daily Starbucks visit and put the £4 daily savings into the equity markets at a 5% annual return I would have about four times the current average national income in the UK in savings on the day I turned 70 (I am 44 now).

Many of you may be uncomfortable with having important stock market expectations simply being based on something as unscientific as historical returns or my ‘guesstimate’ of that data. Perhaps so, but until someone comes up with a reliably better method of predicting stock market returns it’s the best we have and a very decent guide. Also, we know that the equity premium should be something – if there were no expected rewards from investing in the riskier equities we would simply keep our money in low-risk bonds.

Another problem with simplistically predicting a stable risk premium is that we don’t change it in line with the world around us. It probably sits wrong with most investors that the expected returns in future should be the same in the relatively stable period preceding the 2008 crash as it was during the peak of panic and despair in October 2008. Did someone who contemplated investing in the market in the calm of 2006 really expect to be rewarded with the same return as someone who stepped into the mayhem of October 2008?

Someone willing to step into the market at a moment of high panic would expect to be compensated for taking that extra risk, suggesting that the risk premium is not a constant number, but in some way dependent on the risk of the market. At a time of higher expected long-term risk, equity investors will be expecting higher long-term returns. The equity premium outlined above is an expected average based on an average level of risk.

In summary

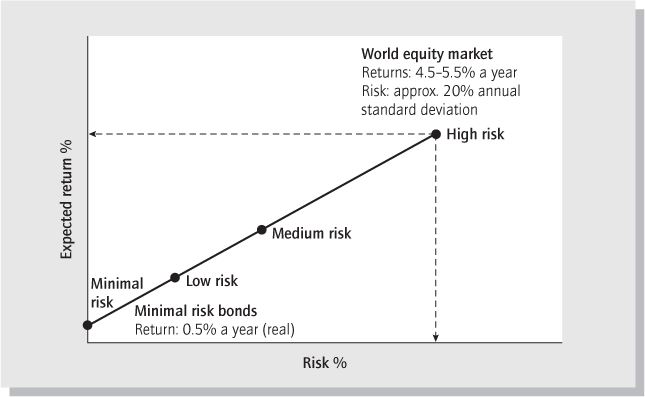

In the interest of making something as complicated as the world financial markets into something almost provocatively simple, Figure 5.8 outlines where we are in terms of returns after inflation.

As an investor who seeks returns in excess of the minimal risk return you can add a broad portfolio of world equities. You can reasonably expect to make a return of 4–5% a year above the rate of minimal risk government bonds, which we expect to be about 0.5% a year, although expect that return to vary significantly for a standard deviation (see Chapter 6) of about 20% a year.

If the world equity markets are too risky for you, combine an investment in that with an investment in the minimal risk bonds to find your preferred level of risk. In brief:

Or you can do any combination of the above that suits your individual circumstances.

Figure 5.8 Risk/return expectations

Buy the broad equity exposure cheaply through index-tracking products. This is important. In the chapter on implementation I will discuss exactly which products you can buy to achieve the exposures above, subject to your tax circumstances (see Chapter 12).

If you do as recommended in this chapter you will, over the long term, do better than the vast majority of investors who pay large fees needlessly and consequently get poorer investment returns. And keep in mind that this portfolio can be created by combining just two index-tracking securities; one tracking your minimal risk asset and one tracking the world equity markets. An excellent portfolio with just two securities (see Figure 5.9): who said investing is difficult?

If this seems too simple, remember that the world equity exposure represents an underlying exposure to a large number of often well-known companies in many currencies all over the world. Your two securities thus get you a mix of amazing diversification along with a minimal risk security that gives you the greatest amount of security possible. How much you want of each depends on the risk/return profile you want.

____________________

1 Some emerging market companies listed their shares on Western exchanges to increase credibility and foreign companies thus make up a meaningful part of some exchanges.

2 The trading set-up may sound cumbersome and expensive, but major product providers naturally have off-setting flows that reduce trading, but are also set up to trade FX (foreign exchange) and stocks very cheaply, or have derivative exposures or sampling that can also reduce costs and keep things simple.

3 Currency-hedged investment products do exist but in my view the ongoing hedging expense adds significant costs without clear benefits, and on occasion further fails to provide an accurate hedge. Besides, many companies have hedging programmes themselves, meaning that a market may already be partially protected against currency moves, or have natural hedges via ownership of assets or operations that trade in foreign currencies (like Petrobras owning oil that trades in US dollars).

4 You can also estimate the equity risk premium by looking at the dividend yield of the stock markets, or the average price/earnings ratio. Combining either of these measures with longer-term earnings growth estimates could also yield an estimate of projected stock market returns. The problem as I see it with either of these measures is that both use quite short-term financial data and combine that with a highly unpredictable long-term growth rate to extrapolate something as uncertain as future stock market returns. Alternatively, some suggest using surveys asking investors what their projections for the market returns are. While interesting (different countries often have very different results) these surveys have been criticised for being heavily sentiment driven and more about a desired return than one actually expected.

5 While the historical risk premium was calculated as a premium to short-term debt, the minimal risk asset return expectation of 0.5% is not as short-term (highly rated real short-term debt returns at the time of writing have negative yields). However, historically the short-term real return has been closer to 0.5% and this is what the equity risk premium is based on. Also, the current yield curve suggests that the negative real interest rate will not last forever.