9

Plans

This chapter covers:

•the role of planning in effective project management

•different types of plan

•product-based planning

•prioritization, estimation and scheduling

•PRINCE2’s requirements for the plans theme

•guidance for effective planning

9 Plans

Key message

The purpose of the plans theme is to facilitate communication and control by defining the means of delivering the products (the where and how, by whom, and estimating the when and how much).

Plans provide the backbone of the management information required for any project; without a plan there can be no control.

Many people think of a plan as just being a chart showing timescales. PRINCE2 takes both a more comprehensive and a more flexible view of plans. A PRINCE2 plan must describe not only timescales but also what will be delivered, how and by whom. Poorly planned projects cause frustration, waste and rework. It is therefore essential to allocate sufficient time for planning to take place.

Definition: Plan

A detailed proposal for doing or achieving something which specifies the what, when, how and by whom it will be achieved. In PRINCE2 there are only the following types of plan: project plan, stage plan, team plan and exception plan.

A plan enables the project team to understand:

•what products need to be delivered

•the risks; both opportunities and threats

•any issues with the definition of scope

•which people, specialist equipment and resources are needed

•when activities and events should happen

•whether targets (for time, cost, quality, scope, benefits and risk) are achievable.

A plan provides a baseline against which progress can be measured and is the basis for securing support for the project, agreeing the scope and gaining commitment to provide the required resources.

Key message

The resources required to deliver a plan need to be committed by those approving that plan to ensure that they are available when needed.

9.1.2 Dealing with the planning horizon

PRINCE2’s principle of manage by stages reflects that it is usually not possible to plan the whole project from the outset. Planning becomes more difficult and uncertain the further into the future it extends. There will be a time period over which it is possible to plan with reasonable accuracy; this is called the ‘planning horizon’. It is seldom possible to plan with any degree of accuracy beyond the planning horizon.

A great deal of effort can be wasted on attempts to plan beyond a sensible planning horizon. For example, a detailed plan to show what each team member is doing for the next 12 months will almost certainly be inaccurate after just a few weeks. A detailed team plan for the short term and an outline plan for the long term is a more effective approach.

PRINCE2 addresses the planning horizon issue by requiring that both high-level and detailed plans are created and maintained at the same time, reflecting the relative certainty and uncertainty on either side of the planning horizon. These are:

•a project plan for the project as a whole. This will usually be a high-level plan, providing indicative timescales, milestones, cost and resource requirements based on estimates

•a detailed stage plan for the current management stage, aligned with the overall project plan timescales. This plan is produced before the start of that stage, and must not extend beyond the planning horizon.

Definition: Project plan

A high-level plan showing the major products of the project, when they will be delivered and at what cost. An initial project plan is presented as part of the PID. This is revised as information on actual progress appears. It is a major control document for the project board to measure actual progress against expectations.

Definition: Stage plan

A detailed plan used as the basis for project management control throughout a management stage.

The management stages make up the project lifecycle and are the fundamental building blocks for the plans and governance of a project. See section 9.3.1.1 for further guidance for designing a plan with management stages.

What is the relationship between project lifecycles, phases and stages?

Project lifecycles are often described in terms of project phases, where the term ‘phase’ is used as an alternative to ‘stage’ or ‘management stage’. For example, BS 6079–1:2010 states:

Most projects, irrespective of size and complexity, will naturally move through a series of distinct phases from conception to completion. This applies as much for sequential development (e.g. analyse, design, build, test) as for iterative and agile development. Generally, the early phases comprise investigative work, which determines the work in the later implementation phases.

In BS 6079 Part 1, there is no assumption regarding the use of the words ‘phase’ or ‘stage’ with respect to level in the work breakdown structure; for example, a stage is not assumed to be a sub-part of a phase or vice versa.

PRINCE2 has a principle to focus on products. The philosophy behind this is that what needs to be delivered (the products) must be identified before deciding what activities, dependencies and resources are required to deliver those products. This approach is called product-based planning.

The benefits of product-based planning include:

•clearly and consistently identifying and documenting the products to be produced by the plan and the interdependencies between them: this reduces the risk of important scope aspects being neglected or overlooked

•removing any ambiguity over what the project is expected to produce

•involving users in specifying the product requirements, thus increasing buy-in and reducing approval disputes

•improving communication: the product breakdown structure and product flow diagram provide simple and powerful means of sharing and discussing options for the scope and approach to be adopted for the project

•clarifying the scope boundary: defining products that are in and out of the scope for the plan and providing a foundation for change control, thus avoiding uncontrolled change or ‘scope creep’

•identifying products that are external to the plan’s scope but are necessary for it to proceed, and allocating them to other projects or organizations

•preparing the way for the production of work packages for suppliers

•gaining a clear agreement on production, review and approval responsibilities.

9.2 PRINCE2’s requirements for the plans theme

To be following PRINCE2, a project must, as a minimum:

•ensure that plans enable the business case to be realized (PRINCE2’s continued business justification principle)

•have at least two management stages: an initiation stage and at least one further management stage. The more complex and risky a project, the more management stages that will be required (PRINCE2’s manage by stages principle)

•produce a project plan for the project as a whole and a stage plan for each management stage (PRINCE2’s manage by stages principle)

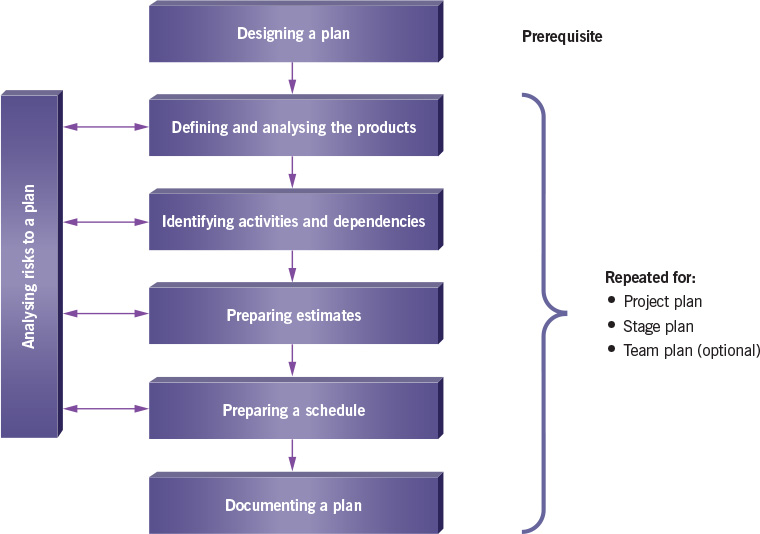

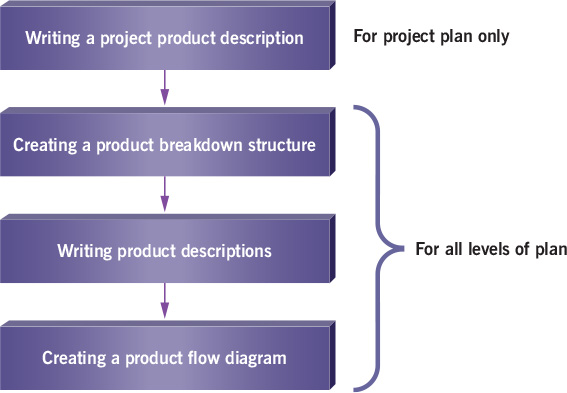

•use product-based planning for the project plan, stage plans and exception plans. It may be optionally used for team plans. PRINCE2 recommends the steps shown in Figure 9.2 for product-based planning although alternative approaches may be used. PRINCE2 recommends the steps shown in Figure 9.6 for defining and analysing the products to produce a product breakdown structure, although alternative approaches may be used

•produce specific plans for managing exceptions (PRINCE2’s manage by exception principle)

•define the roles and responsibilities for planning (PRINCE2’s defined roles and responsibilities principle)

•use lessons to inform planning (PRINCE2’s learn from experience principle).

Key message

PRINCE2 requires a product-oriented approach to decomposing the project product description into a product breakdown structure or a product-oriented work breakdown structure. Where an agile delivery approach is being used, the product breakdown structure could be represented by epics or user stories.

PRINCE2 requires that four products are produced and maintained:

•Project product description A description of the overall project’s output, including the customer’s quality expectations, together with the acceptance criteria and acceptance methods for the project. As such it applies to a project plan only.

•Product description A description of each product’s purpose, composition, derivation and quality criteria.

•Product breakdown structure A hierarchy of all the products to be produced during a plan.

•Plan Provides a statement of how and when objectives are to be achieved, by showing the major products, activities and resources required for the scope of the plan. In PRINCE2, there are three levels of plan: project, stage and team. In addition, PRINCE2 has exception plans, which are created at the same level as the plan they are replacing.

Tip

The terms ‘product breakdown structure’ and ‘work breakdown structure’ can be confusing as definitions of the terminology vary according to different project management professional bodies across the world.

PRINCE2 uses the terminology in the following way:

•A product breakdown structure is a hierarchical breakdown of the products to be produced during a plan; in PRINCE2 a product breakdown structure contains just products.

•A work breakdown structure is a hierarchical breakdown of the entire work that needs to be completed during a plan; in PRINCE2 a work breakdown structure contains just activities.

The PMI’s PMBOK® Guide (Project Management Institute, 2013) defines a work breakdown structure as: ‘A deliverable-oriented hierarchical decomposition of the work to be executed by the project team to accomplish the project objectives and create the required deliverables. It organizes and defines the total scope of work.’

Users of PRINCE2 from a PMI background might find it useful to substitute the phrase ‘product-oriented work breakdown structure’ when they see the term ‘product breakdown structure’ in this manual.

Importantly, both uses of the terminology agree that project managers need to plan by breaking down the products or outputs of the project first and, only then, break down the activity needed to produce the products.

PRINCE2 recommends, but does not require, that an additional product is created and maintained: the product flow diagram. This is a diagram showing the sequence of production and interdependencies of the products listed in a product breakdown structure.

Tip

Although a sequence is implied when defining and analysing products, in practice the product breakdown structure, product descriptions and product flow diagram are often created in parallel.

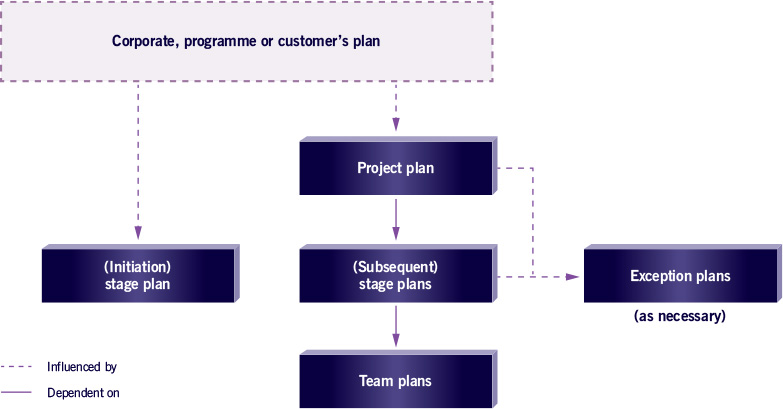

9.2.1 The relationship between the PRINCE2 plans

All PRINCE2 plans have the same fundamental structure and contents; it is the purpose, scope and level of detail in the plans that vary. For this reason, PRINCE2 provides a single ‘plan’ product covering all these plans and Appendix A, section A.16, provides the product description and suggested content.

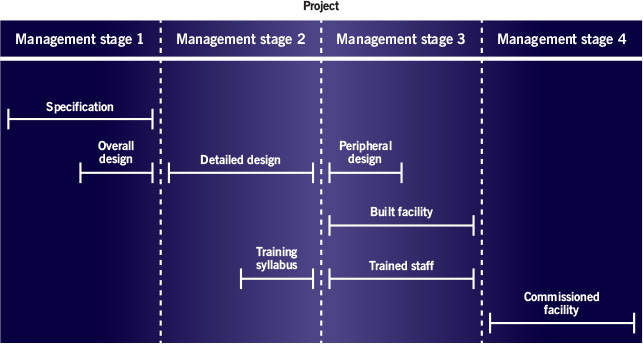

The relationship between these plans is illustrated in Figure 9.1 and each is described below.

The project plan provides a statement of how and when a project’s time, cost, quality and scope performance targets are to be achieved. It shows the major products, activities and resources required for the project and:

•provides the planned project costs and timescales for the business case, and identifies the major control points, such as management stages and milestones

•is used by the project board as a baseline against which to monitor project progress management stage by management stage

•should align with the corporate, programme management or customer plan as appropriate.

The project plan is created during the initiating a project process and updated towards the end of each management stage during the managing a stage boundary process.

A stage plan is required for each management stage. The stage plan is similar to the project plan in content, but each element is broken down to the level of detail required for day-to-day control by the project manager.

A product description is required for all products identified in a stage plan.

The initiation stage plan is created during the starting up a project process, prior to the project plan in the initiating a project process. It is influenced by the corporate, programme management or customer plan (or equivalent) from the organization commissioning the project. All subsequent stage plans are produced near the end of the current management stage when preparing for the next management stage. This approach allows the stage plan to:

•be produced close to the time when the planned events will take place

•exist for a much shorter duration than the project plan, overcoming the planning horizon issue

•be produced with the knowledge of the performance of earlier management stages.

PRINCE2 requires that exception plans are produced where appropriate.

Definition: Exception plan

A plan that often follows an exception report. For a stage plan exception, it covers the period from the present to the end of the current management stage. If the exception is at project level, the project plan will be replaced.

Exception plans must be produced to show the actions required to recover from or avoid a forecast deviation from agreed tolerances in the project plan or a stage plan. See Chapter 12 for more explanation of the use of tolerance in PRINCE2. Exception plans are prepared to the same level of detail as the plan they replace. If approved, the exception plan replaces the plan that is in exception and becomes the new baselined plan.

If a stage plan is being replaced, this needs the approval of the project board. Replacement of a project plan should be referred by the project board to corporate, programme management or the customer if it is beyond the authority of the project board.

Exception plans are not produced for team plans used to manage the delivery of work packages (see section 9.2.1.4).

Each management stage may comprise a number of work packages, each of which may have a detailed team plan.

Definition: Work package

The set of information relevant to the creation of one or more products. It will contain a description of the work, the product description(s), details of any constraints on production, and confirmation of the agreement between the project manager and the person or team manager who is to implement the work package that the work can be done within the constraints.

Definition: Team plan

An optional level of plan used as the basis for team management control when executing work packages.

A team plan is produced by a team manager to facilitate the execution of one or more work packages. These plans are optional and their need and number will be determined by the size and complexity of the project and the number of resources involved. Team plans are created in the managing product delivery process.

There may be more than one team on a project and each team may come from separate organizations following different project management methods (not necessarily PRINCE2). In some customer/supplier contexts it could even be inappropriate for the project manager to see the details of a supplier’s team plan; instead, sufficient, summary information would be provided to enable the project manager to exercise control. The formality of the team plan could vary from simply appending a schedule to the work package to a fully formed plan in similar style to a stage plan.

Should a team manager forecast that the assigned work package may exceed tolerances, they should notify the project manager by raising an issue. If the issue can be resolved within management stage tolerances, the project manager will authorize corrective action by updating the work package or issuing a new work package(s) and instructing the team manager(s) accordingly.

Team managers may create their team plans in parallel with the project manager creating the stage plan for the management stage.

9.2.2 Planning responsibilities in PRINCE2

Responsibilities for planning in PRINCE2 are set out in Table 9.1. As described in Chapter 7, if roles are combined then all the responsibilities in this table must still be covered.

Table 9.1 Responsibilities relevant to the plans theme

Role |

Responsibilities |

Corporate, programme management or the customer |

Set project tolerances and document them in the project mandate or confirm them to the project board for inclusion in the project brief. Approve exception plans when project-level tolerances are forecast to be exceeded. Provide the corporate, programme management or customer planning standards. |

Executive |

Approve the project plan. Define tolerances for each management stage and approve stage plans. Approve exception plans when management-stage-level tolerances are forecast to be exceeded. Commit business resources to stage plans (e.g. finance). |

Senior user |

Assist the project manager in preparing project and stage plans. Ensure that project plans and stage plans remain consistent from the user perspective. Commit user resources to stage plans. |

Senior supplier |

Assist the project manager in preparing project and stage plans. Ensure that project plans and stage plans remain consistent from the supplier perspective. Commit supplier resources to stage plans. |

Project manager |

Design the plans. Prepare the project plan and stage plans. Decide how management stages and delivery steps are to be applied. Instruct corrective action when work-package-level tolerances are forecast to be exceeded. Prepare an exception plan to implement corporate management, programme management or the project board’s decision in response to exception reports. |

Team manager |

Prepare team plans. Prepare schedules for each work package. |

Project assurance |

Review changes to the project plan to see whether there is any impact on the needs of the business or the project business case. Review the management stage and review project progress against agreed tolerances. |

Project support |

Assist with the compilation of project plans, stage plans and team plans. Contribute specialist expertise (e.g. planning tools). Baseline, store and distribute project plans, stage plans and team plans. |

9.3 Guidance for effective planning

9.3.1 PRINCE2’s recommended approach to planning

In the absence of any other approach, PRINCE2 recommends the approach to planning shown in Figure 9.2 and described in the following sections.

The number of management stages

Although the use of management stages in a PRINCE2 project is mandatory, the number of management stages is flexible and depends on the scale, duration and risk of the project. A simple project may only need two stages, the first including initiating the project and the second for undertaking the planned work and closing the project. Larger projects may need additional management stages to enable the project management team to have an optimal level of planning and control.

Defining management stages is fundamentally a process of balancing:

•how far ahead in the project it is sensible to plan

•where the key decision points need to be on the project

•the amount of risk within the project

•too many short management stages (increasing the project management overhead) versus too few lengthy ones (reducing the level of control)

•how confident the project board and project manager are in proceeding.

The length of management stages

PRINCE2 does not define how long a management stage should be. Management stages should be shorter when there is greater risk, uncertainty or complexity (for example, at the beginning of projects). They can be longer when risk is lower, typically in the middle of projects. Factors that will influence this decision include:

•The planning horizon at any point in time The planning horizon may vary depending on the nature of the work being undertaken. For example, the work involved in installing a computer system during an application migration project may be better understood and less risky than the work involved with migrating the application itself.

•The delivery steps within the project The ends of management stages do not necessarily need to occur at the same time as the ends of delivery steps, but there are often benefits if they do. For example, the project board may wish to be able to understand any effects on the business case of the results of a ‘proof of concept’ before committing to a full-scale deployment.

•Alignment with programme activities Programmes may be organized around groups of projects structured around distinct step changes in capability and benefit delivery tranches. It may be a requirement to align the end of a management stage with the end-of-tranche review within the programme. This will allow the project to contribute fully to the assessment of the ongoing viability of the programme itself.

•The level of risk Management stages can be very useful as a means of bringing project board control to risky projects. Management stage breaks can be inserted at key points when risks to the project can be reviewed before major commitments of money or resources.

Management stages and delivery approaches

Another method of grouping work is by the set of techniques used or the products created. This results in a delivery approach covering elements such as design, build and implementation, which are included in the plan as work packages or activities described as delivery steps. Delivery steps are a separate concept from the management stages already introduced, and the work comprising delivery steps is always included within a management stage.

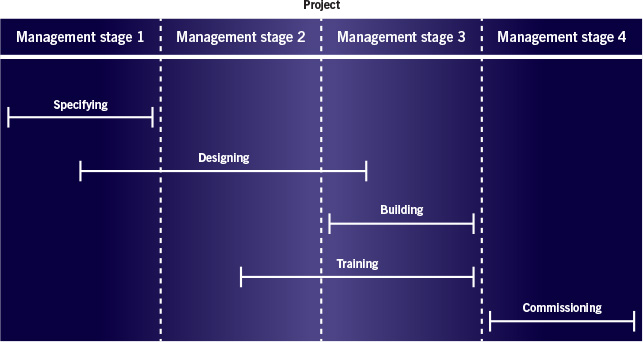

Delivery steps often overlap (as in Figures 9.3 and 9.4) but management stages do not. Delivery steps are typified by the use of a particular set of specialist skills. Management stages equate to commitment of resources and authority to spend.

Often the boundary of the management stage and a delivery step will coincide; for instance, when the management decision is based on the output from delivery activities. However, on other occasions management stage and delivery step boundaries will not coincide; for example, there might be more than one delivery step per management stage.

When a delivery step spans a management stage boundary, the extent to which the product(s) of the delivery step should be complete at the stage boundary should be clear in the product description(s) concerned.

Figures 9.3 to 9.5 give examples of the distinction between management stages and delivery steps. Figure 9.3 shows a project with five delivery steps. The numbered management stages in Figures 9.4 and 9.5 show a sequence of stages within a project (not from the start of the project).

Figure 9.4 shows the same project as Figure 9.3, but broken down into four management stages. Two of the delivery steps span more than one management stage.

Figure 9.5 shows a ‘designing’ delivery step that has been broken into three product groups:

•The overall design now falls within management stage 1.

•Detailed design and training syllabus form the second management stage.

•Peripheral design is scheduled for management stage 3, together with the creation of the built facility and trained staff.

The PRINCE2 approach is to concentrate the management of the project on the management stages because these will form the basis of the planning and control processes described throughout the method. To do otherwise runs the risk of the project being driven by the specialist teams instead of the customer’s management.

The format and presentation of the plan

Decisions need to be made about how the plan can best be presented, depending on the audience for the plan and how it will be used, together with the presentation and layout of the plan, planning tools, estimating methods, levels of plan and monitoring methods to be used for the project.

PRINCE2 does not prescribe a format for a plan. Charts, documents, spreadsheets and plans on whiteboards are all equally valid if they are fit for purpose and appropriate to the scale, planning horizon and complexity of the project.

If the project is part of a programme or portfolio, the programme or portfolio may have developed a common approach to project planning. This may cover standards (e.g. level of planning) and tools. These will be the starting point for designing any project plan. Any project-specific variations should be highlighted and the agreement of programme or portfolio management sought. There may also be a company standard for planning and control aids, or the customer may stipulate the use of a particular set of tools. The choice of planning tool may depend on the complexity of the project and so the choice may need to be deferred until the level of complexity is known.

The estimating methods to be used in the plan may affect the plan design, so decisions on the methods should be made as part of the plan design itself.

The use of planning tools is not obligatory, but it can save a great deal of time if the plan is to be regularly updated and changed. A good tool can also validate that the correct dependencies have been built in and have not been affected by any plan updates.

Tip

The plan for a simple project may be very simple, such as a product checklist or a diagram on a whiteboard in the workroom, which can be photographed from time to time.

9.3.1.2 Defining and analysing the products

PRINCE2 recommends, but does not mandate, the following approach (summarized in Figure 9.6).

Writing a project product description

The project product description is created in the starting up a project process as part of the initial scoping activity. It may be refined during the initiating a project process when creating the project plan. It is subject to formal change control and should be checked at management stage boundaries (during the managing a stage boundary process) to see if any changes are required. It is used in the closing a project process as part of the verification that the project has delivered what was expected of it and that the acceptance criteria have been met.

Although the senior user is responsible for specifying the project product, in practice the project product description is often written by the project manager in consultation with the senior user and executive. The project product description is included as a component of the project brief and is used to help select the project approach defined within the project brief. The project product description defines what the customer is expecting the project to deliver and the project approach defines the solution or method to be used by the supplier to create the project product.

Every effort should be made to make the project product description as complete as possible at the outset. See Appendix A, section A.21, for the suggested composition of the project product description.

Tip

If the project’s scope includes any transition or business change (necessary to deliver outcomes), these should also be defined as specialist products and explicitly covered in the plan.

Creating a product breakdown structure

The plan is broken down into its major products, which are then further broken down until an appropriate level of detail for the plan is reached. A lower-level product can be a component of only one higher-level product. The resultant hierarchy of products is known as a product breakdown structure.

The format and presentation of the product breakdown structure and product flow diagram are determined by personal preference. See Appendix D for examples.

When creating a product breakdown structure, consider the following:

•It is usual to involve a team of people in the creation of a product breakdown structure, perhaps representing the different interests and various skill sets involved in the plan’s output.

•It is common to identify products by running a structured brainstorming session (e.g. using sticky notes or a whiteboard) to capture each product as it is identified.

•When a team is creating a product breakdown structure, there are likely to be different opinions on how to break down the products. For example, if the output of the plan is accounting software, users may want separate modules for accounts payable, accounts receivable, general ledger, etc. The suppliers, however, may prefer screens, reports, databases, etc. Neither breakdown is wrong, but the project management team must agree on which approach will be used in the product breakdown structure (and hence the plan).

•It is useful to identify any products that are required to be created by other projects, or purchased or hired directly from a supplier; these are externally sourced products. The project manager is not responsible for the creation of externally sourced products as they will be supplied by parties outside the project team. The project team will, however, be responsible for the specification of the externally sourced products that are created. Consideration should be given to identifying threats to the plan should the externally sourced products be late or not to the required specification.

•When using product-based planning, it is important to consider whether to include different states of a particular product. An example of product states is ‘dismantled machinery, moved machinery and reassembled machinery’. It could be appropriate to identify the different states as separate products, where each state would require its own product description with different quality criteria and quality controls. This may be particularly useful when the responsibility for creating each state will pass from one team to another. Alternatively, a single product description could be used with a set of quality criteria that the product needs to meet in order to gain approval for each state.

•When presenting the product breakdown structure, consider the use of different shapes, styles or colours for different types of product. For example, a rectangle could be used in a product breakdown structure to represent most types of product, but it may be helpful to use different shapes (such as ellipses or circles) to distinguish externally sourced products. Colours could be used to indicate which team is responsible for the product or in which management stage the product will be created.

•If the project is broken down into several stages, the products for each management stage are extracted from the project product breakdown structure to form the management stage product breakdown structure. These may be expanded to more levels of detail and thus ‘extra products’ may be added to give the detail required of the stage plan. Care must be taken to use the same names in the stage plans as were used in the project plan. The creation of stage plans may cause rethinking that requires further modification of the project plan in order to retain consistency.

•In some cases, the organization’s lifecycle model may have a preset product breakdown structure and product flow diagram for common types of projects and a library of product description outlines for common products. In such cases the steps in the PRINCE2 approach to product-based planning should not be skipped but used to verify the completeness of any library material. As every project is unique, there may be additional product requirements for the project or subtle differences in the quality criteria; the locations may be different, or the people and responsibilities involved may be different. Moreover, lifecycle models frequently address only one aspect of a project’s scope.

Writing product descriptions

A product description is used to understand the detailed nature, purpose, function and appearance of a product. It is produced as soon as the need for the product is identified.

When creating a product description, consider the following:

•Product descriptions should be written as soon as possible after the need for the product has been identified. Initially, these may only be ‘skeletons’ with little more than the title and identifier as information. They will be refined and amended as the product becomes better understood and the later planning steps are done. Therefore, early in planning ‘write’ (as in write a product description) can mean ‘start to write and complete as soon as information becomes available’.

•A product description should be baselined when the plan containing the creation of that product is baselined. If the product is later changed, the product description must also pass through change control.

•Although the responsibility for writing product descriptions rests officially with the project or team manager, it is wise to involve representatives from the area with expertise in the product and those who will use the product in question. The latter should certainly be consulted when defining the quality criteria for the product.

•Successful product descriptions may be reused for other projects within that programme or organization. For this to happen, a library of product descriptions for reuse will need to be established and a mechanism for product descriptions to be placed in the library will also need to be implemented. The project manager should therefore refer to the library in order to see if any of the product descriptions within it are suitable for reuse and/or modification for the project.

•If a detailed requirements specification for a product is already available, this may be used as a substitute for the product description as long as the requirements specification covers the components and meets the quality criteria expected of a product description. Alternatively, a product description should be created referencing the requirements specification contents where appropriate.

•For a small project, it may only be necessary to write the project product description and product descriptions for the major/most important products.

•Quality criteria, aimed at separating an acceptable product from an unacceptable one, need careful thought. One way of testing quality criteria is by asking the question: How will I know when work on this product is finished as opposed to stopped?

•When using an agile approach it is important to remember that the initial versions of product descriptions are likely to only address the purpose and quality criteria for the product, with the rest developed during the execution of the work package.

Creating a product flow diagram

A product flow diagram may be helpful in identifying and defining the sequence in which the products of the plan will be developed and any dependencies between them (see Figure D.4 in Appendix D for an example of a product flow diagram).

The product flow diagram also helps to identify dependencies on any products outside the scope of the plan. It leads naturally to the consideration of the activities required, and provides the information for other planning techniques, such as estimating and scheduling.

When creating a product flow diagram, consider the following:

•Although the project or team manager is responsible for the creation of the product flow diagram, it is sensible to involve those who are to develop or contribute to the products contained in the plan.

•Rather than preparing the product flow diagram after the product breakdown structure has been drawn, some planners prefer to create the product flow diagram in parallel with the product breakdown structure.

•A product flow diagram needs very few symbols. Each product to be developed within the plan in question is identified (e.g. it may be enclosed in a rectangle), and the sequence in which they are to be created is shown (e.g. the rectangles may be connected by arrows). Any products that already exist or that come from work outside the scope of the project plan should be clearly identified as products to be sourced externally to the project (e.g. they may be enclosed in a different shape, such as an ellipse).

•It may be useful to add a starting point in the product flow diagram to which all entry points are attached. There is always one exit on a product flow diagram, but when there are many entrances such a place marker prevents any from being overlooked. The symbol becomes the predecessor for all entry points and would be the only symbol on a product flow diagram that is not on the product breakdown structure.

•The product flow diagram may be derived from a benefits map (linking outputs, outcomes and benefits), thereby ensuring the project product will deliver the outputs and outcomes required in order to realize the benefits.

9.3.1.3 Identifying activities and dependencies

Simply identifying products is not sufficient for scheduling and control purposes. The activities required to create or change each of the planned products need to be identified to give a fuller picture of the plan’s workload.

There are several ways to identify activities, including:

•making a separate list of the activities, while still using the product flow diagram as the source of the information

•taking the products from the product breakdown structure and creating a work breakdown structure to define the activities required.

The activities should include management and quality checking activities as well as the activities needed to develop the specialist products. The activities should include any that are required to interact with external parties; for example, obtaining a product from an external source or converting such externally sourced products into something that the plan requires.

Tip

Avoid a proliferation of activities beyond the detail appropriate to the level of the plan.

After the activities have been identified, any dependencies between activities (and products) should also be identified. It is important that dependencies are captured (e.g. on the product flow diagram or some form of register) and that someone responsible for managing the dependency is identified (the project manager or some other nominated person). Key dependencies should be noted in the project plan. Consideration should be given to identifying threats to the plan related to dependencies.

Definition: Dependency

A dependency means that one activity is dependent on another. There are at least two types of dependency relevant to a project: internal and external.

An internal dependency is one between two project activities. In these circumstances the project team has control over the dependency.

An external dependency is one between a project activity and a non-project activity, where non-project activities are undertaken by people who are not part of the project team. In these circumstances the project team does not have complete control over the dependency.

A decision about how much time and resource are required to carry out a piece of work to acceptable standards of performance must be made by:

•identifying the type of resource required. Specific skills may be required depending on the type and complexity of the plan. Requirements may include non-human resources, such as equipment, travel or money

•estimating the effort required for each activity by resource type. At this point, the estimates will be approximate and therefore provisional.

Tip

Basic rules for estimating

Many books and software packages include some basic rules to help ensure that an accurate and realistic estimate is produced. Examples of such planning rules include the following:

•Assume that resources will only be productive for, say, 80 per cent of their time.

•Resources working on multiple projects take longer to complete tasks because of time lost switching between them.

•People are generally optimistic and often underestimate how long tasks will take.

•Make use of other people’s experiences and your own.

•Ensure that the person responsible for creating the product is also responsible for creating the effort estimates.

•Always make provision for problem-solving, meetings and other unexpected events.

•Cost each activity rather than trying to cost the plan as a whole.

•Communicate any assumptions, exclusions or constraints you have to the user(s).

Estimating cannot guarantee accuracy but, when applied, provides a view about the overall cost and time required to complete the plan. Estimates will inevitably change as more is discovered about the project.

Estimates should be challenged, as the same work under the same conditions can be estimated differently by various estimators or by the same estimator at different times.

A plan can only show the ultimate feasibility of achieving its objectives when the activities are put together in a schedule that defines when each activity will be carried out.

There are many different approaches to scheduling. Scheduling can either be done manually or by using a computer-based planning and control tool.

Defining an activity sequence

Having identified the activities and their dependencies, and estimated their duration and effort, the next task is to determine the optimal sequence in which they can be performed.

This is an iterative task as the assignment of actual resources may affect the estimated effort and duration.

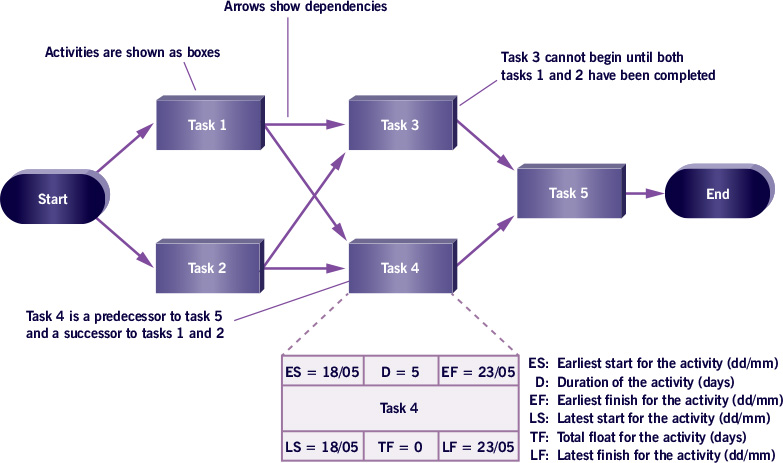

The amount of time that an activity can be delayed without affecting the completion time of the overall plan is known as the float (sometimes referred to as the slack). The float can either be regarded as a provision within the plan, or as spare time.

The critical path(s) through the diagram is the sequence of activities that have zero float. Thus, if any activity on the critical path(s) finishes late, then the whole plan will also finish late (e.g. if task 4 in Figure 9.7 is delayed, then completion of the plan will be delayed).

Identifying a plan’s critical path enables the project manager to monitor those activities that:

•must be completed on time for the whole plan to be completed to schedule

•can be delayed for a time period if resources need to be re-allocated to catch up on missed activities.

Example of activity-on-node technique

An activity-on-node diagram (sometimes called an arrow diagram) can be used to schedule dependent activities within a plan. It helps a project manager to work out the most efficient sequence of events needed to complete any plan and enables the creation of a realistic schedule.

The activity-on-node diagram displays interdependencies between activities through the use of boxes and arrows. Arrows pointing into an activity box come from its predecessor activities, which must be completed before the activity can start. Arrows pointing out of an activity box go to its successor activities, which cannot start until at least this activity is complete (assuming a finish-to-start relationship between the activities). A simple activity-on-node diagram is shown in Figure 9.7.

Assessing resource availability

The number of people who will be available to do the work (or the cost of buying in resources) should be established. Any specific information should be noted (e.g. names, levels of experience, percentage availability, available dates).

Assigning resources

Using the resource availability and the information from the activity sequence allows the project manager to assign resources to activities. The result will be a schedule that shows the loading of work on each person, and the use of non-human resources.

A useful approach is to allocate resources to those activities with zero slack first (by definition they are on the critical path). Those activities with the greatest slack are the lowest priority for resource allocation.

It is important that task owners are defined. If a group needs to complete a task, ask one person from the group to be accountable to the group for that task.

If any of the task owners do not participate in creating the schedule, make sure of their availability and willingness to own the task. Do not assume that putting their names on a plan or schedule will automatically get the work done. Collaborate, communicate and follow up with each task owner to make sure that they understand what it means to complete the task.

When assigning resources, it is important to recheck the critical path because the actual resources assigned may be more or less productive than the assumption made when calculating activity effort and duration.

Levelling resource usage

The first allocation of resources may lead to uneven resource usage or over-utilization of some resources. It may therefore be necessary to rearrange resources; this is called levelling.

Activities may be reassigned, or they may have start dates and durations changed within the slack available. The end result is a final schedule with all activities assigned and resource utilization equating to resource availability.

Agreeing control points

The draft schedule enables the control points to be confirmed by the project board.

Activities relating to the end of a management stage (e.g. preparing the end stage report and the next stage plan) should be added to the activity network and the schedule revised.

One common mistake when creating a schedule is not to allow time for approvals of products or releases.

Defining milestones

A milestone is an event on a schedule which marks the completion of key activities. This could be the completion of a work package, a delivery step or a management stage. In a commercial environment, reaching a milestone may be the trigger for a payment to a supplier.

Breaking the plan into intervals associated with a milestone allows the project manager to have an early indication of issues associated with the schedule itself, and also a better view of the activities whose completion is critical to the timeline of the plan.

Although there is no ‘correct’ number of milestones or duration between them, they lose their value when there are too many or too few. There should be far fewer milestones than deliverables or work packages, but there should be enough milestones at major intervals to gauge whether or not the plan is proceeding as expected.

Calculating total resource requirements and costs

The resource requirements can be tabulated, and the cost of the resources and other costs calculated to produce the plan’s budget. The budget should include:

•costs of the activities (including people, equipment and materials) to develop and verify the specialist products, and the cost of the project management activities

•risk budget (see section 10.3.7)

•change budget (see section 11.3.6)

The use of risk budgets and change budgets is optional.

Having completed the schedule satisfactorily, the plan, its costs, the required controls and its supporting text need to be consolidated in accordance with the plan design. Some examples of schedule presentation techniques are provided in section 9.4.3.

Narrative needs to be added to explain the plan, any constraints on it, external dependencies, assumptions made, any monitoring and control required, the risks identified and their required responses. This initial plan will be reviewed and updated throughout the life of the project as further information clarifies any assumptions made.

Tip

It is a good discipline to keep plans as simple as is appropriate. Consider summary diagrams if the plan is to be presented to the project board.

It may be sensible to have one plan format for presentation in submissions seeking approval, and a more detailed format for day-to-day control purposes. Also consider different levels of presentation of the plan for the different levels of readership. Most planning software offers such options.

9.3.1.7 Analysing risks to a plan

This planning activity will typically run in parallel with the other planning steps, as risks may be identified at any point in the creation or revision of a plan.

Each resource and activity, and all the planning information, should be examined for its potential risk content. All identified risks should be entered into the risk register (or the daily log when planning the initiation stage).

After the plan has been produced, it should still be considered a draft until the inherent risks in the plan have been identified and assessed, and the plan possibly modified.

See Chapter 10 for more details on identifying and analysing risks.

Examples of planning risks

•Omission of plans at the appropriate management level(s).

•Lots of resources joining the project at the same time can slow progress and cause communication issues. For example, plotting an S-curve (see section 12.4.1) for the resource profile over time can identify this; steep curves should be avoided.

•The plan includes unnamed resources, causing the productivity of the actual resource to differ from the estimated productivity in the plan.

•The plan contains a high proportion of external dependencies.

•The plan uses untested suppliers or is dependent on new technologies.

•There is a high proportion of activities on the critical path; a delay to any one of them will delay the plan.

•The plan does not allow for sufficient management decision points such as management stage boundaries.

•There is not much float in the plan (creating a histogram showing the number of activities by amount of float is a useful way of identifying this risk).

•A large number of products are to be completed at the same time.

•The plan is time-bound by fiscal boundaries (e.g. the budget cannot be transferred from this year to the next) or by calendar boundaries (e.g. preparation for a major sporting event).

•The schedule shows that many paths running closely in parallel with the critical path are likely to become critical themselves if there is a minor slip.

9.3.2 Plans for projects within a programme

Any specific standards that the project planners should work to will be described in the programme’s monitoring and control strategy (the document that describes how a programme will apply internal controls to itself).

The programme may have dedicated planners that can help the project manager prepare and maintain the project plan and stage plans.

The programme dependency network will detail which of the project’s deliverables are being used by other projects within the programme. Any such dependencies to or from the project should be incorporated into the project’s plans.

The number and length of management stages will be influenced by the programme plan. It may be desirable or necessary to align stage reviews to programme milestones (e.g. the end of a tranche). The programme may even define a set of standard management stages with which all projects within the programme comply.

9.3.3 Plans when using an agile approach

Product-based planning can be applied very easily to agile delivery and it is important to plan around the requirements being delivered. Many agile techniques and concepts exist in this area. They focus on how much can be delivered over a fixed period of time (e.g. a sprint or a timebox) and often appear in an informal, lowtech, visible format such as a simple list or backlog.

When agile is being used, a common approach would consist of:

•the starting up a project process, producing the vision and product roadmap

•a management stage for the initiating a project process, producing the product backlog

•then a series of delivery management stages containing releases of (groups of) requirements/features.

The first two items could be combined.

There may be other equally valid ways to construct plans for projects using agile delivery approaches.

9.3.4 Plans from a supplier perspective

When tailoring the plans theme for a customer/supplier situation it must be clear, through the contract, how the plans are to be produced and what rights of inspection and audit the customer has. A supplier’s plan should have sufficient activities and/or milestones for the customer’s project manager to maintain their plans.

Plans need to include procurement-related milestones such as purchase orders and milestone payments aligned with each management stage.

Both the customer’s and supplier’s plans may be confidential to the other party as they may contain other information such as dependencies to or from other client projects, subcontractor costs, etc. It is therefore beneficial to prepare non-confidential versions of the plan that can be shared, omitting private information.

9.4 Techniques: prioritization, estimation and scheduling

9.4.1 The MoSCoW prioritization technique

Projects seldom have the money, time or resources to deliver everything wanted by the business, users or suppliers, even if delivery of everything has a business justification.

This means that on most projects acceptance criteria and quality criteria need to be prioritized, with the project attempting to deliver as much as is possible and for which there is a business justification.

In the absence of any other approach, PRINCE2 recommends the use of a technique called MoSCoW as a general prioritization technique. MoSCoW stands for:

•Must have

•Should have

•Could have

•Won’t have.

Only those things identified as ‘must have’ are guaranteed to be delivered by a project.

MoSCoW can be used in a range of prioritization contexts, such as prioritizing issues and changes. In the context of acceptance criteria and quality criteria the following definitions apply:

•Must have The acceptance criteria or quality criteria define what is essential and critical to the business justification of the project. This would include failing to meet a legal or regulatory requirement.

If the business justification for the project is viable without the criteria, even if it would involve undesirable workarounds, then the criteria are not ‘must haves’.

•Should have The acceptance or quality criteria define what is important, but not critical, to the business justification of the project. Their absence materially weakens the business justification.

•Could have The acceptance or quality criteria define what is useful, but not critical, to the business justification of the project. Their absence does not weaken the business justification.

In practical terms the distinction between should have and could have can be difficult to make. In practice it is often determined by:

•a level of impact on the business justification. For example, a criterion might be considered ‘should have’ if it has greater than 1 per cent impact on benefits

•an assessment of the actual or perceived impact of not having satisfied the requirement. For example, a ‘no manual workarounds’ restriction might be the difference between should have and could have.

•Won’t have The acceptance criteria or quality criteria define what has been considered but will not be delivered. Even though it might appear strange to record what is not going to be delivered by a project, doing so is often powerful as it formalizes an agreement to not deliver something. This acts as a reminder that something has been consciously considered and can avoid the requirements being reintroduced at a later date.

MoSCoW can be used for other types of prioritization, such as prioritizing changes, by adapting the criteria as necessary. When MoSCoW is used in this way, the criteria for must have, should have and could have should always be based on the impact on business justification, in line with PRINCE2’s continued business justification principle.

The MoSCoW technique can also help to define scope tolerances, supporting the manage by exception principle.

9.4.2 Estimating techniques Examples of estimating techniques

Examples of estimating techniques

Top-down estimating

When a good overall estimate has been arrived at for the plan (by whatever means), it can be subdivided through the levels of the product breakdown structure. By way of example, historically development may be 50 per cent of the total resource requirement and testing may be 25 per cent. Subdivide development and testing into their components and apportion the effort accordingly.

Bottom-up estimating

Each individual piece of work is estimated on its own merit. These are then added together to find the estimated efforts for the various summary-level activities and overall plan.

Top-down and bottom-up approach

An overall estimate is calculated for the plan. Individual estimates are then calculated, or drawn from previous plans, to represent the relative weights of the tasks. The overall estimate is then apportioned across the various summary- and detailed-level tasks using the bottom-up figures as weights.

Comparative (reference class) estimating

Much data exists about the effort required and the duration of particular items of work. Over time an organization may build up its own historical data regarding projects that it has undertaken (previous experience and captured lessons). If such data exists, it may be useful to reference it for similar projects and apply that data to the estimates.

Parametric estimating

Basing estimates on measured/empirical data where possible (e.g. estimating models exist in the construction industry that predict materials, effort and duration based on the specification of a building).

Single-point estimating

The use of sample data to calculate a single value which is to serve as a ‘best guess’ for the duration of an activity.

Three-point estimating

Ask appropriately skilled resource(s) for their best-case, most likely and worst-case estimates. The value that the project manager should choose is the weighted average of these three estimates.

Delphi technique

This relies on obtaining group input for ideas and problem-solving without requiring face-to-face participation. It uses a series of questionnaires interspersed with information summaries and feedback from preceding responses to achieve an estimate.

Planning poker (when using an agile approach)

A group uses specially numbered playing cards to vote for an estimate of an item. Voting repeats with discussion until all votes are unanimous.

Big/uncertain/small (when using an agile approach)

Items to be estimated are placed by the group in one of three categories: big, uncertain and small. The group starts by discussing a few items together and then uses a divide-and-conquer approach to go through the rest of the items.

Examples of presentation formats for the schedule

Gantt charts

A Gantt chart is a graphical representation of the duration of tasks against the progression of time. It allows the project manager to:

•assess how long a plan should take

•lay out the order in which tasks need to be carried out

•manage the dependencies between tasks

•see what should have been achieved at a certain point in time

•see how remedial action may bring the plan back on course.

Critical path diagram

A critical path diagram highlights those tasks which cannot be delayed without causing the plan to be delayed, and those tasks that can be delayed without affecting the end date of the plan. It helps with monitoring and communication.

Spreadsheets

It is possible to create a list of tasks ‘down’ the spreadsheet and a timeline ‘across’ it, then colour in the cells to represent where the tasks will occur in the timeline, and progress to date. For simple projects where the timeline is unlikely to change, this may be adequate. For large or complex projects, the timeline may change frequently. This means that the project manager may spend a significant amount of time changing the schedule while neglecting the day-to-day tasks required to manage the project.

Product checklist

A product checklist is a list of the major products of a plan, plus key dates in their delivery. An example of a product checklist is shown in the product description outline for a plan in Appendix A, section A.16.