Chapter 10

Dreaming of the Consumer’s Delight: Per fect Competition

In This Chapter

![]() Introducing perfect competition

Introducing perfect competition

![]() Understanding the requirements for a perfectly competitive market

Understanding the requirements for a perfectly competitive market

![]() Explaining why perfect competition is a benchmark

Explaining why perfect competition is a benchmark

Is perfection attainable? Although from time to time you may use the term casually (“I’ve made the perfect cappuccino,” “Reality TV shows are a perfect nuisance,” and of course, “This is the perfect book on microeconomics!”), most people understand that achieving perfection in the real world is impossible. But that doesn’t mean that they can’t imagine the perfect situation.

Perfect competition is the name economists give to a market with many interchangeable firms, none of which can independently influence the market outcome. This scenario isn’t all that likely in the real world, because it depends on a set of conditions that are unlikely to hold. But some markets do get quite close to approximating perfect competition; of course, many others do not come close. When they do get close, they bring a number of benefits, which are most likely to go to consumers.

In this chapter, we look at the equilibrium of output and price in perfect competition — an ideal situation that economists use as a benchmark. We go through some of the conditions that determine which markets are oh so perfect and which fall below the standard. We also discuss the important factors of firm entry and exit, which lie behind the model of the perfectly competitive market. Do we have your attention? Perfect!

Viewing the “Perfect” in Perfect Competition

The word perfect means something very specific to economists. This section outlines what exactly that is and discusses some of the necessary conditions for perfect competition.

Defining perfect competition

By way of an analogy, economists mean perfect competition in the same way as mathematicians describe a perfect circle as exactly satisfying a set of mathematical conditions regarding curvature.

Identifying the conditions of perfect competition

- Each firm is small relative to the market and has no influence on price.

- Firms and products are substitutable.

- Each consumer is small relative to the market and has no influence on price.

- Perfect information about prices and quantities is available.

- There is easy entry into and exit from the market.

We go through them all in a little more detail in this section.

Each firm is small relative to the market

In a perfectly competitive market, no firm is individually able to influence the price or quantity sold of a given good. For this to be the case, each firm has to be a small producer relative to the quantity demanded. Typically, this means there are many firms to supply the market, none of which has a significant share of the market. This is obviously not always the case in many markets, because many markets are dominated by one firm or a small group of firms.

Firms and products are substitutable

Products in a perfectly competitive market are said to be homogenous, that is, indistinguishable from one another. If, for example, you’re shopping at a fruit and veg market with many sellers (so that none can influence the price paid for apples), the apples that each sells must be the same: no better or worse apples and no stalls that are the only ones selling Macintosh or the only ones selling Granny Smith. Instead, all must be selling the same, indistinguishable product.

Similarly, the firms must have the same production technology. If they don’t, long-run differences between firms are possible, which leads to differences between the firms in the market. This would open up the possibility of one firm being different enough from the other firms to be considered as being in a different market altogether and to be able to influence that market.

Each consumer is small relative to the market

A similar issue is the degree to which consumers are small relative to the market. This means that there is not a consumer whose purchasing behavior is able to influence the price. For many markets, this is a pretty plausible condition. A regular at Starbucks does not influence the price of a latte. However, a large pharmacy chain such as CVS is likely to be able to influence the price it pays for the prescribed medications it sells to consumers.

Perfect information about products and prices

A perfectly competitive market contains no hidden surprises. Consumers are perfectly informed about what products are available, the qualities of the products, where they are sold, and at what prices. Thus they’re immediately able to assess whether they want to purchase from one firm or another.

Easy entry and exit

Easy entry into and exit from the market is an extremely important condition. If an entrepreneur sees profits being made in a perfectly competitive market, he’s able to enter that market immediately and begin competing profits away from the firms in the market. Similarly, if he’s in a market and not making profits, he’s able to pack up and leave without his leaving incurring any costs that can’t be recovered.

Putting the Conditions Together for the Perfectly Competitive Marketplace

In a long-run equilibrium in a perfectly competitive market, firms make economic profits (those assessed after all costs have been reckoned) equal to zero and produce output at the minimum possible cost. Zero economic profit does not mean that the shareholders of the firm are losing — rather, it means that the rate of return they are earning is comparable to what they could earn elsewhere in the economy. To see why economic profits are zero and productive efficiency holds in the long-run equilibrium of a perfectly competitive market, this section investigates the equilibrium conditions for perfect competition. (To read more about supply, demand, and equilibrium, check out Chapter 9.)

Seeing the supply side

Firms in perfectly competitive markets are price takers. To understand the competitive position among the firms in a competitive market, it is helpful to look at the supply decisions an individual firm will make. This means that if you want to see what’s happening in the market, you have to return to looking at the firm’s cost curves (see Chapter 7 for a full explanation).

The thing is, in perfect competition the assumption that market entry and exit for firms is costless means that supply in a perfectly competitive market looks a little different. What we’re going to do first is show you how horizontal addition works to get the figure for industry supply in the short run.

We use the example of the paper clip industry. Table 10-1 shows the output of three firms in the paper clip industry for three different values of marginal costs. At a marginal cost of 1, for instance, firm A makes 10 paper clips, B makes 11, and C makes 12. To get the industry supply in the short run, you add up the output of A, B, and C at each of the three marginal costs — so when all competitors produce at a marginal cost of 1, industry supply is 10 + 11 + 12, which equals 33.

Table 10-1 Marginal Cost and Industry Output in the Paper Clip Industry

|

Firm Marginal Cost |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Output per firm |

|||

|

A |

10 |

11 |

13 |

|

B |

11 |

12 |

15 |

|

C |

12 |

14 |

17 |

|

Total |

33 |

37 |

45 |

The supply curve for the industry gives the relationship between output and cost for the industry. Adding up the marginal costs for each of the firms provides the short-run supply curve for the industry.

Now, because firms are price takers, profit maximization means that marginal revenue is equal to price is equal to marginal cost or MR = p = MC. Table 10-2 shows industry output for three different prices. (You may notice that industry output is the same as in the bottom row of Table 10-1. The difference is that we’re using the marginal cost equals price relationship to make the inference that makes up the supply curve.)

Table 10-2 Supply Curve for the Paper Clip Industry

|

Price |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Industry output |

33 |

37 |

45 |

When you plot the output for the three firms, you get the typical upward-sloping supply curve (see Figure 10-1). Using the relationship between marginal cost and marginal revenue equal to price, you can express the profit-maximizing supply with price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis, and lo and behold, you can say that if the market price of a box of paper clips is 3, then the industry would produce 45 boxes. In other words, the sum of the marginal costs of the firms in the industry leads to an output equal to 45 when marginal cost is equal to 3.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 10-1: Adding marginal costs horizontally to make industry supply.

This situation is fine for looking at most cases of industry supply and market demand, but the costless entry and exit condition in the long run (check out the earlier section “Identifying the conditions of perfect competition”) adds something new to how we work out supply in the long run.

Marginal, as usual in economics, means at the margin. At the margin, only one firm is deciding whether to enter the industry, stay in it, or leave it. At equilibrium, the marginal firm will have no preference between those decisions. How can that possibly be the case? Well, given the profit-maximizing rule for firms — that production is set where marginal revenue equals marginal cost (see Chapter 3) — you know that this can happen only when a firm receives exactly as much for its last unit of output as the incremental amount it cost to produce it. At equilibrium in perfect competition, therefore, economists look at the marginal revenue received by the last firm and find that it must equal the marginal cost of producing that output. The marginal condition holds in the short run where capital (for example, production facilities) or the number of firms is fixed and in the long run when the condition refers to the last firm to enter the industry.

Digging into the demand side

The preceding section’s discussion on supply is a start, but you also need to look at the other side of the market — demand — to get the market equilibrium.

Here’s another way of understanding what it means to not be able to influence market price. Imagine that you’re in the middle of an aisle of many vegetable sellers in an outdoor market. They all sell identical yams and tell you their prices by clearly barking them out so that getting that information involves no cost to you. They’re all very near to each other too, so you incur no cost going from one to another to find a yam for your dinner (sounds yummy!).

For argument’s sake, assume that yams are on sale at the market cost of $1 per pound. But then imagine that one seller has the ability to get hold of yams for less and can therefore bring them to the market for 90 cents. You hear his price, and immediately realize (as a rational consumer) that his price being lower means that you can buy more and (following the model of the consumer in Chapters 4–6) make yourself better off by doing so. You’re economically rational, so it’s a no-brainer. You buy from the cheaper seller.

But you aren’t alone in this market — you’re only one of many rational consumers. All the other consumers in the market have also heard his price, and they all want to have more utility rather than less. So they all follow, leaving all the other sellers barking their prices to precisely no one.

When you get to the cheaper seller, you find him looking absolutely exhausted. The entire market has come to him, and he can’t possibly keep up. His stock is going to run out, leaving him scratching around trying to find more yams to sell. What does he do? He has no choice. He’s going to have to put his price back up to the market price — as stated in the earlier section “Identifying the conditions of perfect competition,” he’s a price taker — and return to market equilibrium.

Returning to equilibrium in perfect competition

This section aims to put supply and demand together to get equilibrium (where, of course, supply equals demand). In the earlier section “Seeing the supply side,” we state why we consider the marginal firm. We now combine what we know about the marginal firm with what we deduced about demand to consider what happens when the marginal firm meets the rational consumer in perfect competition.

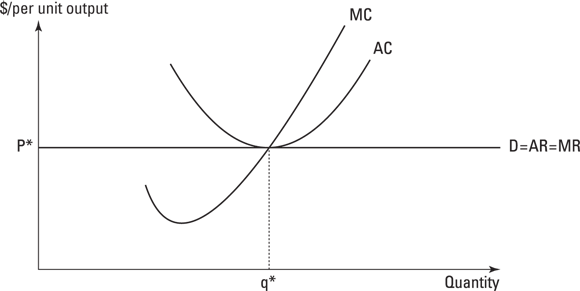

Economists are only interested in the marginal firm out of all the firms, and we can understand the output in the industry by just using the cost curves for that one firm. (To revise cost curves, pop over to Chapters 7 and 8. Don’t worry, we’ll still be here.) Figure 10-2 puts the equilibrium conditions into a picture.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 10-2: Equilibrium for the marginal firm in perfect competition.

The demand curve facing a firm describes not only price or average revenue, but because it’s horizontal and perfectly elastic, it describes the marginal revenue gained from selling an additional unit to a customer. Putting them together, as in Figure 10-2, the marginal firm sets output, assuming it is a rational profit maximizer, so that MC = MR, thus producing where the marginal cost curve crosses its demand curve.

![]()

Π is profit. You can get TR (total revenue) and TC (total cost) from the demand or average revenue function and from the average cost function. If you multiply AC by quantity (q), you get TC. Similarly, if you multiply average revenue (AR) by q, you get TR. Thus you can divide through by taking the quantity out of the cost and revenue terms:

![]()

In a long-run equilibrium, the marginal firm is just indifferent between entering and not entering the market, and this means that it must earn zero profit. Average revenue equals average cost, or that (AR – AC) has to equal zero so that if you multiply zero by quantity, you get zero. Moreover, in the long run, the marginal firm must be producing at the minimum possible average cost (AC) — otherwise, there is potential profit to be earned by changing output and lowering average cost. So there you have it: Profits for the marginal firm in perfect competition have to equal zero, and the firm is producing at minimum average cost.

Now let’s go back to the example of the vegetable sellers from the preceding section. Suppose the equilibrium price of a delicious package of veggies is $10 per package, which is equal to the unit cost of a package, and the seller prices the package at $9. What happens next? Well, first the seller is now pricing in a way that TR < TC. If that’s the case, the seller will make losses and have to decide whether to go on selling in this market.

Now what if the price is above average cost? Well, in this case you can work out from the equation that the seller now makes economic profits above zero. But then other entrepreneurs see the marginal veggie seller making economic profits and so are attracted to enter. They then compete away those profits until the point where the marginal firm is indifferent between staying in the industry and leaving it. In other words, after they enter, the marginal seller or firm, again, makes economic profits of precisely zero.

Thus in the long run — which economists define as that length of time it takes for all production decisions to be changeable — the marginal firm in a perfectly competitive industry makes economic profits of zero.

Examining Efficiency and Perfect Competition

- Allocative efficiency: The market price for a product equals the marginal cost of producing it.

- Productive efficiency: The firm produces for the lowest possible average cost.

Both these conditions are satisfied in perfect competition, which means that from the overall viewpoint of cost, equilibrium in perfect competition is allocatively and productively efficient. Thus, on the grounds of cost, perfect competition produces the most desired products for the lowest possible cost.

Understanding that perfect competition is a boundary case

We draw an analogy with an engineer’s concept of perfect efficiency, where 100 percent of the energy put into a machine gets transformed into useful work. In reality, that’s not true. But investigating the case where it does apply, as a model, the engineer is able to understand the degree to which her machine falls short of ideal and explore the reasons for it.

Economists use the idea of perfect competition in a similar way. Few markets in the world, if any, satisfy all the conditions of a perfectly competitive market, but that’s not why economists are interested in its features. The real reason is to enable some comparison of the efficiency of a given market with that of the perfectly competitive market, and to assess the degree to which it falls short.

Also, although the zero profit condition and selling at a price equal to minimum average cost may sound nice in theory, in practice profits don’t just get stacked in a bank vault. They can also be retained for investment — for instance, in research and development (R&D) of new products. R&D is often an intensive and expensive process, and most economists point out that firms that don’t make long-run profits have less capital to spend on R&D and less incentive to make that investment. Thus high levels of competition may have a drag effect on levels of R&D investment and not be conducive to forming research-intensive companies and developing new technologies.

Considering perfect competition in the (imperfect) real world

Often students ask whether the model of perfect competition is realistic or whether it’s just a textbook case. Our answer is that it may almost happen in some situations, and although they’re interesting, the primary interest in perfect competition is more as a benchmark for understanding the effects of competition. Examples in this chapter include a commodity market (because commodities are homogeneous products) with many buyers and sellers, such as a fruit and vegetable market. Perhaps the closest example is something like Uber offering taxi services in a town where there are many potential drivers and users. In this case, you could expect to get quite close to the perfectly competitive situation. Confronted with a market like this, each driver would be making close to zero economic profits as a whole. They may be making a salary’s worth of money, but remember that the salary is the opportunity cost of their time and car use.

Perfect in the sense of perfect competition means that it fully satisfies a set of conditions that economists have placed on the model.

Perfect in the sense of perfect competition means that it fully satisfies a set of conditions that economists have placed on the model. The term certainly doesn’t mean that in a perfectly competitive market everyone’s always happier. In fact, for producers, a perfectly competitive market may be a difficult one in which to operate, because the forces of competition constrain their behavior.

The term certainly doesn’t mean that in a perfectly competitive market everyone’s always happier. In fact, for producers, a perfectly competitive market may be a difficult one in which to operate, because the forces of competition constrain their behavior. This condition doesn’t mean that starting up involves no costs — just that it doesn’t involve any costs above and beyond those of producing whatever he’s producing in that market: no fees for entering and no costs of closing.

This condition doesn’t mean that starting up involves no costs — just that it doesn’t involve any costs above and beyond those of producing whatever he’s producing in that market: no fees for entering and no costs of closing. This sounds wonderful, but it is important to remember that the key requirement for a perfectly competitive market is that each firm is small relative to the market and cannot influence market price. We live in a world where firms such as Apple, Toyota, Walmart, Anheuser-Busch InBev, and Comcast are large relative to the market and can influence market price. If Toyota stopped producing cars or Walmart shut down all its stores, there would be an impact on market prices. These firms do not face perfectly elastic demand curves — they have market influence or market power.

This sounds wonderful, but it is important to remember that the key requirement for a perfectly competitive market is that each firm is small relative to the market and cannot influence market price. We live in a world where firms such as Apple, Toyota, Walmart, Anheuser-Busch InBev, and Comcast are large relative to the market and can influence market price. If Toyota stopped producing cars or Walmart shut down all its stores, there would be an impact on market prices. These firms do not face perfectly elastic demand curves — they have market influence or market power.