Chapter 3

Looking at the Behavior of Firms: What They Are and What They Do

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding the firm as an economic organization

Understanding the firm as an economic organization

![]() Understanding how microeconomists view firms

Understanding how microeconomists view firms

![]() Thinking about why people form companies

Thinking about why people form companies

One of the key insights into how a market economy organizes production is the concept in microeconomics of a firm: an entity or agent that produces things. This description is very general, necessarily, because in the real world many different types of organization can be called a firm. For simplicity, we start from an assumption that all these firms are of the same type — even if we give them many different names in reality — and share similar essential features.

In this chapter, we expand on the general description and then firm up (sorry!) a few of the concepts that underlie the production that firms undertake. We look at some of the different structures of firms and some of the critical problems associated with organization. After reading this chapter you’ll have a firm (oh no, not again!) grasp of how firms form the backbone of production in a market economy.

Delving into Firms and What They Do

The best approach to start thinking about the firm is in a simple way, by considering the smallest possible unit of production: a single-person-operated firm such as a market stall (in the U.S., this is called sole proprietor). This section also introduces you briefly to other types of firms.

Recognizing the importance of profit

![]()

The equation says that the total profit the firm makes is the difference between all revenues that the firm takes in and all costs that the firm incurs to conduct its activities.

At this stage, you haven’t done anything to break down those costs into corresponding production activities (we do so in Chapter 7), and so for the moment we suggest that the sole proprietor’s costs include not only the cost of goods bought in and the cost of labor, but also the fixed costs of its operation, that is, the rent due on the stall irrespective of how many things are sold individually.

At heart, economists treat every firm in this way. Of course, firms vary considerably in size and complexity, and comparing the activities of a transnational corporation to a market stall trader would be a little simplistic. But all firms share in common the profit motivation, and profit is the indicator of revenues being in excess of costs. A rational firm (in economic terms) seeks to maximize it.

Discovering types of firms

Many firms are of course significantly more complex than the sole proprietor mentioned in the preceding section.

- Partnership: There are several owners of the firm that are permitted to share in any profits generated by its business and are equally liable for all its losses.

- Limited liability company (LLC): An entity that the law defines as owning the profits which may then be redistributed to those who own the company, called shareholders. In a limited liability company, shareholders are only liable for losses up to the stake they hold in the company.

- Co-operative: Owned and operated by its members. Typically, it redistributes profits to those members.

Considering How Economists View Firms: The Black Box

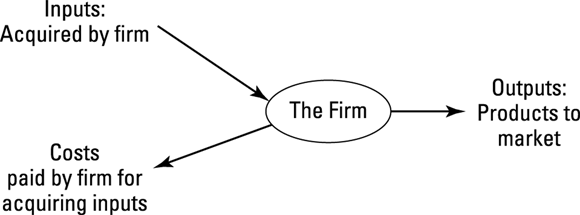

Economists are often accused of treating firms too simply. By disregarding differences in organizational behavior, technology, or place, and by treating firms more simply as a kind of black box that takes inputs in and creates outputs from them, are economists painting a misleading picture that makes firms interchangeable and ignores important differences between them?

Economists have faced this accusation many times, and so in this section we describe why economists view firms as they do.

Seeing why economists think as they do

Economists are interested in how the profit motive affects what a firm would do, first and foremost. When they understand that, they can start to look at how firm behavior differs across different industries or markets.

- You can’t build a model without placing some restrictions on your model. If you rule nothing out, you rule anything in, and before you know it you’ve reenacted the Lewis Carroll story about the map so accurate that it has to be as big as the kingdom it maps.

- You want to compare common features of firms, without focusing on all those details, so that you can zero in on the ones that are most important to building a model of a market.

Peering inside the Black Box: Technologies

The preceding section’s rationale doesn’t mean that economists take the nature of changing inputs into outputs for granted. Since Adam Smith, economists have been describing in various ways the methods a firm can use to transform inputs into outputs, which they call technologies.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-1: The microeconomist’s view of a firm.

The inputs that go into a technology are called the factors of production. The three most common factors of production are

- Land

- Labor

- Capital

Let’s take a closer look at each factor in turn.

Land: They ain’t makin’ any more of it

Land is without doubt an important factor of production, but it tends to be studied apart from other inputs. Land costs can be significant and important to the firm, taking up the greater fraction of operating costs for businesses in some places. Land costs can be made worse by restrictions on bringing new land into use or preventing new uses for old land — for instance, in turning former agricultural land into housing.

Labor: Getting the job done

The human element of production is labor, usually denoted by L and typically measured in man-hours per week. The firm hires labor by paying wages, w, per man-hour to the workers who are hired to do the work. Thus the total a firm pays out in labor costs is w times L, or wL.

To begin with, economists assume that workers are indistinguishable and undifferentiated so that each worker makes the same contribution to output. This is only where things begin, though, because later, when you’ve got the hang of the general picture, you can use a variety of more advanced tools to look at various differences between or among workers and how these differences affect output or costs. But for the moment, assume that workers are the same and that each one is neither harder working nor shirking.

Capital: Tangible and intangible

Labor is important, but workers can’t create an output on their own without at least some equipment. Carpenters need woodworking tools, and authors need nice flashy laptops, or at least yellow legal pads and pens. Therefore, labor has to be combined with the other factor of production: capital.

- Tangible capital: Includes physical capital such as tools, machines, and plant equipment, often measured in machine-hours. A machine is durable and is able to yield a certain number of machine-hours before it breaks down and has to be replaced.

- Intangible capital: Includes such assets as brand value and the knowledge and skills embodied in the firm. (Skills embodied in labor are often called human capital.)

In each case, the capital plus labor combine to make the output, and so capital is generally held to be useless on its own. The cost of a unit of capital is denoted by r. This isn’t quite the same as the interest rate, because it has to cover the opportunity cost of doing something else with your money rather than buying or investing in capital. If r goes up, then the purchase of capital or investment by firms falls because of the following:

- If the firm has to borrow money to increase its use of capital at a higher cost of borrowing, the firm has to borrow more money to invest in the capital it wants.

- If the firm is investing its own money, then a higher cost of capital implies that the opportunity cost of investing is higher and that a firm wants higher returns to capital to compare with other opportunities. Therefore, the firm is likely to use less capital.

You can use a number of techniques to evaluate the costs of using and deploying capital, most of which are based on how investors discount the receipt of revenue earned in the future or discounting the value of future earnings and costs so that future and present costs and benefits can be compared.

Minimizing costs

A firm with a given technology makes a choice about how much of each of the factors of production to use to make how much output — and pays the cost for doing so. The question for the firm is how to use its technology and choose its inputs in order to make its profits as large as possible. The way it does so is to choose its inputs in order to make the costs as small as possible (see Figure 3-2). The technology shown in the figure is a specific form known as a Cobb-Douglas production function.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 3-2: An example of how an economist looks at a technology.

If you’re wondering why economists think this way, consider profit maximization (discussed in detail in Chapter 8). In the following equation (introduced in the earlier section “Recognizing the importance of profit”), profit equals the difference between total revenue and total cost:

![]()

Maximizing profits

When discussing a firm, economists generally assume that the firm wants to maximize profits — in other words, that the difference between total revenue and total costs is positive and as large as possible. Economists don’t think there’s anything immoral about profit maximization. Rather, they believe that profit maximization is a goal that helps a firm be efficient, and firms that don’t make profits tend not to operate as firms for very long.

Of course, some nuances apply to this view of profit. For one, the existence of profits in the economist’s sense says nothing about how those profits may be distributed. For example, an LLC may want to retain some profits for future investment and return some to shareholders as dividends. But although a nonprofit company still intends to make a surplus (as it would be called in the accounts, reflecting the different legal as opposed to economic definition of the company), it does different things with that surplus, which may include distribution to workers or to chosen worthy causes.

- Tax systems where company taxes fall on profits can provide an incentive to declare lower levels of profit.

- Managers may have different incentives than shareholders and prefer to generate higher salaries for themselves than higher profits for the company (managers’ wages here would be a cost to the company).

- A company may prefer to evaluate its performance using some other measure, such as sales or market share, at least in the short run. Some examples include companies in online markets where interim measures commonly used include market share or number of users.

Is this a problem for microeconomists? Not necessarily. In most situations, they want to make a simplification that helps them understand the world instead of covering every possible case. So, when considering different types of markets the benchmark of the profit-maximizing firm helps economists consider how they may be similar or different.

From Firm to Company: Why People Form Limited Liability Companies

Many economic activities require rather more than simply buying something and selling it on. These stages of creating the product involve more complex forms of organization than our example of the sole trader. Consider, for example, the set of production processes involved in making the computers we’re using to write and publish this book: dealing with contractors; managing international product development; creating the complementary products (software and operating systems); and managing the people and processes involved. As a result, a structure that places all these activities into one entity can bring a number of advantages.

Also, the LLC is only one potential structure among many in which people could do this. Over human history, people have used a number of other organizations to arrange production: armies, hierarchies — literally a rule of priests — and various kinds of state actors have all been involved in the production process. Some key advantages, however, apply to arranging production in an LLC:

- Shareholders are liable only for losses up to the extent of their ownership stakes. By having many shareholders, the limited liability company structure allows for the spreading of risk among shareholders, which in turn allows the company to raise capital more easily.

- Having a pool of capital sources for a company to draw upon is important to understanding how firms grow.

Although reasonably compelling reasons exist for some types of investor to favor the LLC structure, pooling activities into a single entity also provides an additional advantage. The eminent economist Ronald Coase first pointed out in the 1960s that in reality, using the market might not be free and costless, especially if you have to search for and transact with many different people in order to do business — which is, in itself, a cost.

Why would anyone want to separate ownership from management? Aside from the advantages of diffusing ownership in an LLC (which includes greater sources of capital for a company and some protection against losses for an owner), a shareholder may have shares in many different companies. Could such a shareholder be able to manage all those companies full time? Not unless the person was some type of shareholding superhero. So in each venture, companies need to appoint professional managers.

But this arrangement doesn’t work perfectly, in all situations. The principal-agent problem is how we describe the kinds of problems that can arise.

Commonly, they choose to reward management with shares in the company, which has the advantage of aligning the interests of shareholders and managers. Steve Jobs, famously, was only paid $1 in salary when he returned to Apple as CEO in 1997 — the rest of his salary was paid in shares.

The evidence on management share schemes or employee share schemes is mixed, with the variation in schemes making it hard to draw an overall conclusion on whether or how these incentive schemes benefit firms.

- The stakeholder model sees the firm as being the nexus of all societal interests.

- The shareholder model sees only shareholders as being relevant or important.

Fashions for describing firms have changed several times in recent history. The American Academy of Management, for instance, pronounced in favor of the stakeholder model in the 1970s, changed to the shareholder model in the 1980s, and then back to the stakeholder model in the late 1990s.

Looking at this sole proprietor firm, an economist would want to make some general statements about what it does, and why it does it. Therefore, microeconomists abstract away any particular features such as special features about its operation that aren’t generalizable across industries or markets unless they’re absolutely necessary. The simplest way to do this is to turn to the foundation of business and accounting and make some general statements about the costs and benefits that accrue. (To find out why economists think of firms this way, check out the later section “

Looking at this sole proprietor firm, an economist would want to make some general statements about what it does, and why it does it. Therefore, microeconomists abstract away any particular features such as special features about its operation that aren’t generalizable across industries or markets unless they’re absolutely necessary. The simplest way to do this is to turn to the foundation of business and accounting and make some general statements about the costs and benefits that accrue. (To find out why economists think of firms this way, check out the later section “ Economists take a more general view on profit than accountants, and to an economist there is only one way to measure profit.

Economists take a more general view on profit than accountants, and to an economist there is only one way to measure profit. Company law distinguishes a few types of firms according to how profits or losses earned by the firm are distributed, including:

Company law distinguishes a few types of firms according to how profits or losses earned by the firm are distributed, including: But beyond this consideration, other reasons may exist why a firm may not be acting as a profit maximizer:

But beyond this consideration, other reasons may exist why a firm may not be acting as a profit maximizer: