2

HOW TO CREATE A CULTURE OF ABUNDANCE

Organizational culture is one of the most important predictors of high levels of performance over time.1 Organizations that flourish have developed a culture of abundance, which builds the collective capabilities of all members. It is characterized by the presence of numerous positive energizers throughout the system, including embedded virtuous practices, adaptive learning, meaningfulness and profound purpose, engaged members, and positive leadership. There is plenty of empirical evidence that organizations displaying a culture of abundance have significantly higher levels of performance than others.2 Since creating a culture of abundance almost always implies culture change, this chapter discusses five basic steps that positive leaders can use to facilitate such a change: creating readiness for change, overcoming resistance to change, articulating a vision of abundance, generating commitment to that vision, and making the new culture sustainable over time.

WHAT IS ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE?

When we speak of an organization’s culture, we are referring to the taken-for-granted values, expectations, collective memories, and implicit meanings that define that organization’s core identity and behavior. Culture reflects the prevailing ideology that people carry inside their heads. It provides unwritten and usually unspoken guidelines for what is acceptable and what is not. Culture is largely invisible until it is challenged or contradicted. We do not wake up each morning, for example, making a conscious choice to speak our dominant language—in my case, English. We are not aware that we speak a certain language until we meet someone who does not, calling our attention to what we take for granted. And because culture is undetectable most of the time, it is difficult to manage or change.

At the most fundamental level, culture can be characterized as the implicit assumptions that define the human condition and its relationship to the environment. Figure 5 illustrates the different levels and manifestations of culture, from the taken-for-granted and unobservable elements to the more overt and noticeable elements.

At the very foundation of culture lies human virtues—what all human beings consider to be right and good, and what allows human beings to be their very best. These are implicit assumptions. Freedom, justice, compassion, kindness, faith, charity, courage, and love are among the attributes that all human beings assume to be right and good. Implicit assumptions and values give rise to social contracts and norms. These are the conventions and procedures that govern how humans interact—including rules of etiquette, civility, and courtesy. Artifacts are manifestations of culture that are more observable and overt, such as the buildings in which we live, the clothes we wear, the entertainment we enjoy, and the logos, flags, graffiti, and decorations we use to identify ourselves. The most obvious manifestation of culture is the explicit behavior of members of the culture. In a group or organization, this is the way in which people interact, the language that is expected, or the ways in which relationships are formed.

FIGURE 5

Organizational Culture

When leaders attempt to foster a change in culture, they usually begin by encouraging change in overt behaviors and observable features. By themselves, these kinds of changes do not signal a cultural shift, but they begin the process of deeper and more fundamental culture change. The challenge for positive leaders is to ensure that these initial efforts to establish abundance become embedded and institutionalized, so that culture change actually occurs. The sustainability of abundance is the goal. A quote from Mahatma Gandhi describes this process: “Keep your thoughts positive, because your thoughts become your words. Keep your words positive, because your words become your behavior. Keep your behavior positive, because your behavior becomes your habits. Keep your habits positive, because your habits become your values. Keep your values positive, because your values become your destiny.”3

Positive leaders know that a culture change has occurred when members of the organization begin to think in new ways, change their paradigms or the categories they use to make sense of their environments, alter the meaning associated with their activities, focus on possibilities instead of just probabilities, and experience a change in ideology.

AN EXAMPLE OF CULTURE CHANGE: GENERAL MOTORS

In the 1980s General Motors built a production facility in Fremont, California, where the Chevrolet Nova auto-mobile was assembled. The plant operated at a disastrously low level of productivity. Absenteeism averaged 20 percent, and approximately five thousand grievances were filed each year by employees at the plant—the same as the total number of workers. Three or four times each year, workers just walked off the job in wildcat strikes. Sales were trending downward, and ratings of quality, productivity, and customer satisfaction were the worst in the company. Because of this disastrous performance, GM shuttered the plant and laid off all the workers.

Then, in the interest of trying to create a culture change, General Motors approached Toyota to design and build a car as a joint venture. Toyota jumped at the chance to work with what was at the time the world’s largest auto company. The Fremont facility was selected as the site for this joint venture, and approximately eighteen months after being idled, the plant was reopened. Two years after the restart of operations, absenteeism was 2 percent, no strikes had occurred, and sales, productivity, quality, and customer satisfaction were the highest in General Motors.

One of the production employees who had worked at the plant for more than twenty years, both under the old regime and then in the new joint venture, was asked to describe the changes that occurred after Toyota and General Motors joined forces. Before the plant was closed, employees felt they had no real stake in the organization; consequently, many of them would deliberately think up ways to mess up the system. This employee would leave part of his sandwich behind the door panel of a car, for example. A month later, the customer who bought the car would notice a terrible smell but not be able to figure out where it was coming from. Or he would put loose screws in a compartment of the frame that was to be welded shut so that the rattle could be heard throughout the entire frame of the car.

After the plant reopened under the joint venture, a new company culture was created in which employees were encouraged to adopt positive ways of thinking about the company and their role in it. For example, each employee was allowed to choose his or her job title. This worker, whose job was to monitor robots that spot-welded parts of the frame together, selected the title, “Director of Welding Improvement.” All employees were given business cards with their new title as a symbol of a new culture of abundance. One result was a dramatic change in the sense of ownership and engagement: “Now when I go to a San Francisco 49ers game or a Golden State Warriors game or a shopping mall,” this worker said, “I look for our cars in the parking lot. When I see one, I take out my business card and write on the back of it, ‘I made your car. Any problems, call me.’ I put my card under the windshield wiper. I do it because I feel personally responsible for those cars.”4

This example illustrates a fundamental culture change—a gut-level, values-centered, in-the-bones change in what is assumed to be right and acceptable. Employees adopted a different way to think about the company and their roles in it, with the result that productivity, quality, efficiency, and morale improved significantly. Ample empirical evidence confirms that an abundance culture and virtuous practices in organizations lead to dramatic positive impacts on performance and effectiveness.5

In the rest of this chapter you will find a series of practical steps shown in Figure 6 for developing a culture of abundance: creating readiness, overcoming resistance, articulating a vision of abundance, generating commitment, and fostering sustainability. It is important to stress that each of the steps is necessary—each relies on and reinforces the ones that come before. This means that if any one step is skipped, culture change will not occur. It is also essential to note that although these steps stimulate the process of culture change, they do not guarantee it. Culture change takes time and persistence, but applying these steps is a proven way to produce a culture of abundance.

FIGURE 6

Creating a Culture of Abundance

CREATING READINESS

One way to create readiness for culture change is to compare current levels of performance to the highest standards you can find. Identifying who else performs at spectacular levels, studying those best practices in detail, and then identifying ways to exceed them permits you to set a standard toward which people can aspire. It identifies a target of opportunity.

Identifying best practices does not mean copying or mimicking. Rather, it means capturing new information, new ideas, and new perspectives and learning from them.

Here are several kinds of standards you can use for comparison.

Comparative standards: comparing current performance to leading individuals or organizations (e.g., “How are we doing relative to our best competitors?”)

Goal standards: comparing current performance to publicly stated goals (e.g., “How are we doing compared to the aspirational goals we have established?”)

Improvement standards: comparing current performance with improvements made in the past (e.g., “How are we doing compared to our past improvement trends?”)

Ideal standards: comparing current performance with an ideal or perfect standard (e.g., “How are we doing relative to a zero-defect standard?”)

Stakeholder expectations: comparing current performance with the expectations of customers, employees, or other stakeholders (e.g., “How are we doing in helping customers flourish?”)

Activity

Creating Readiness Through Comparisons

To help create readiness for culture change and to identify aspirational standards, consider the following list of activities. Select two or three to implement as an initial step in fostering a culture change.

• Identify others doing the same tasks better than you are.

• Host visitors who can share feedback about your work environment.

• Sponsor learning events such as guest lectures, symposia, or conferences.

• Create study teams and task forces to identify best practices.

• Schedule visits to other sites or locations.

• Identify problems associated with the status quo and advantages of a change.

• Identify WIIFM—What’s In It For Me—for those being affected.

Another way to create readiness for change is to change the language people in the organization use. Over and over again it has been shown that when new language is used, perspectives change. For example, Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus observed that the most successful leaders in education, government, business, the arts, and the military are those who have developed a special language in which the word failure does not appear.6 Instead, they use alternative descriptors, such as temporary slowdown, false start, miscue, error, blooper, stumble, foul-up, obstacle, disappointment, or nonsuccess. These leaders use an alternative language in order to interpret reality for their organizations in a way that fosters a willingness to try again and promotes an inclination toward a culture of abundance.

For example, a variety of organizations refer to employees as teammates, associates, family members, or even (at the Ritz-Carlton hotel chain) ladies and gentlemen. This language is intended to establish a culture of behavioral expectations and values. At the Disney Corporation, employees were hired by “central casting,” not the human resources department. They were referred to as “cast members”; regardless of their jobs, they wore “costumes,” not uniforms; they served “guests” and “audience members,” not tourists; they worked in “attractions,” not offices, stores, or rides; they played “characters” in the show (even as groundskeepers), not merely worked in a job; during working hours, they were “onstage” and had to go “offstage” to relax, eat, or socialize.

The intent of an alternative language is to change the way individuals think about their work, their role, and their values. It places them in a mind-set that they would not have considered otherwise. Changing language helps unfreeze old interpretations and create new ones, and using positive language does that in a positive manner. You may have heard that making people uncomfortable creates readiness for change. Often that does work, but it also leads to defensiveness, fear, crisis, and negative reactions. Developing a culture of abundance, on the other hand, focuses on creating readiness in ways that unlock positive motivations rather than resistance and provides optimistic alternatives rather than fear.

Activity

Creating Readiness Through Language

Select alternative terms for important aspects of your organization or your workplace that capture the values, the feelings, and the culture that you want to reinforce. Most often these alternative terms are words, but you could also use logos or symbols. The intent is to use language or symbols that communicate the culture that you want to build, as in the examples below.

Aspect of Organization |

Alternative Label |

Employees |

Colleagues |

Customers |

Guests |

Work space |

Playground |

Break space |

Fun factory |

Tasks |

Games |

Materials |

Resources |

Outcomes |

Pursuit of perfection |

Measures |

Accountability |

Media |

Image builder |

What language, logos, or symbols might you use to create readiness?

OVERCOMING RESISTANCE

Most changes are uncomfortable, but this is especially true of culture change. Deeply held beliefs and assumptions are challenged, not to mention the disruption of interpersonal relationships, power and status, and routine ways of behaving in organizations. Culture change is usually interpreted as a negative condition, so resistance is likely. The role of the positive leader is to overcome resistance and change it into positive energy.

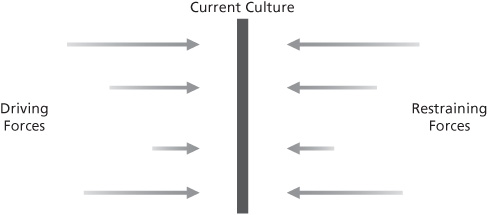

One way to think of resistance is to use Kurt Lewin’s field theory of change.7 This theory uses force field analysis to diagnose and overcome resistance. According to the theory, the current culture is a product of multiple forces working in opposite directions, as demonstrated in Figure 7.

On one side of the model are restraining forces, or resistance factors, that inhibit change. On the other side of the model are driving forces, or motivators, that encourage improvement and culture change. The culture is stable in its present form because the driving forces are exactly balanced with the restraining forces. The lines on each side of the Figure represent forces that are equal and balanced, explaining the organization’s current culture.

Positive culture change results from an imbalance of forces. Overcoming resistance to culture change, therefore, involves weakening or eliminating restraining forces as well as strengthening and adding driving forces (see Figure 8).

FIGURE 8

Force Field Analysis and Culture Change

Reducing Restraining Forces

One well-known strategy for reducing resistance is to involve those who are most affected by the change. They can be asked to gather data, assist in implementation, help project outcomes and consequences, or communicate with others. Resistance is reduced when individuals believe that they have a say in the change agenda, have relevant information available to them, and are given some discretion or choice.

Another frequently used strategy is to find areas of common agreement between those who are pushing for change and those who are resisting it. This builds on the well-known negotiation technique of finding something on which the parties agree and then building from there. This is especially true when the advocates of change display empathy and understanding regarding the opposing point of view. Showing genuine caring for people who are resisting change helps preserve their self-esteem and avoids creating the impression that their point of view is irrelevant, ignorant, or invalid.

Still another strategy is to highlight what will not change even after the new culture is developed. Reinforcing what is familiar and comfortable as well as what will be preserved help reduce ambiguity, uncertainty, and anxiety. Resistors can safeguard at least some elements of the culture that are familiar.

Increasing Driving Forces

A well-known strategy for enhancing and strengthening positive driving forces is to identify benefits, future opportunities, and desirable outcomes. For example, what advantages will be provided by the new culture? A related technique is to highlight past successes and achievements that are linked with the preferred culture. For example, what evidence exists that a change toward the new culture leads to more success or more opportunities to flourish?

The more power and prestige held by the champions of change, the less resistance there will be among other members of the organization. Therefore, another strategy for strengthening driving forces is to obtain the support of powerful or influential individuals, build coalitions of recognized or admired people, and create “change teams” consisting of positively energizing people. People who uplift and energize others can help reduce resistance by being messengers and advocates.

Bennis, Benne, and Chin found that individuals would rather follow leaders who display a consistent set of values—even if they disagree with those values—than leaders whose values are ambiguous or unstable8 Lawrence Kohlberg found that the most influential change agents are those who display a consistent, comprehensive, universalistic set of values that clarify what they stand for.9 Thus, another strategy for increasing driving forces is to clarify and exemplify a core set of values and virtues upon which the new abundance culture will be based. Because virtuousness is heliotropic, people are inclined to follow leaders who create a culture based on core values and virtues.

Activity

Overcoming Resistance

The lists below illustrate some ways to overcome resistance. For your own organization, identify practices that will reduce resistance forces as well as increase drive forces.

Reduce Restraining Forces

• Involve others

• Find areas of agreement

• Identify what won’t change

Increase Driving Forces

• Identify benefits

• Form coalitions and identify champions

• Establish and demonstrate a core set of values

ARTICULATING A VISION OF ABUNDANCE

When you have created readiness and reduced resistance, the people in your organization still need to know what the new culture will be like. This is where articulating a vision of abundance comes in: picturing the organization as a source of flourishing and as an entity that creates a legacy about which people care deeply. This kind of vision helps unleash human potential, since it addresses the basic human desire to do something that makes a difference, something that has enduring impact.

Visions of abundance are different from visions of goal achievement or effectiveness, such as earning a certain level of profit, becoming number one in the marketplace, or receiving recognition. Rather, a vision of abundance speaks to the heart as well as the head. It attracts people by appealing to both the left and right sides of the human brain and by making the vision interesting.

Appealing to Both Sides of the Brain

The brain is divided into two halves. The left hemisphere controls rational, cognitive activities such as sequential thinking, logic, deduction, numeric thought, and so on. Activities such as reading, solving math problems, and rational analysis are dominated by left-brain thinking. The right hemisphere, in contrast, controls nonrational cognitive activities such as intuition, creativity, fantasy, emotions, pictorial images, and imagination. Composing music, storytelling, and artistic creation are tied to right-brain thinking.

Neither hemisphere operates autonomously from the other, and this illustrates why vision statements must appeal to both left-brain and right-brain elements. Targets, goals, and action plans (left-brain components) must be supplemented by metaphors, colorful language, and imagination (right-brain components). Unfortunately, most organizational vision statements are almost exclusively left-brain dominant. They focus much more on objectives, processes, and desired outcomes than they do on emotions, imagery, and virtue.

To articulate the left-brain elements of the vision for your organization, answer the following questions:

• What are our most important strengths as an organization?

• Where do we have a strategic advantage?

• What major problems and obstacles do we need to address?

• What stands in the way of significant improvement?

• What are the primary resources that we need?

• What information do we require?

• Who are our key customers?

• What must be done to respond to stakeholder expectations?

• What measurable outcomes will we accomplish?

• What are the criteria to be monitored?

To articulate the right-brain elements of the vision for your organization, answer the following questions:

• What is the highest aspiration we can achieve?

• What have we done in the past that represents spectacularly positive performance?

• What stories can we tell or events can we describe that illustrate what we stand for?

• What metaphors or analogies can we use that epitomize our ideal future?

• What symbols are appropriate for helping capture people’s imaginations?

• What colorful and inspirational language can exemplify what we believe in?

• What logos or images can people rally around?

• What do we care most deeply about that should be pursued?

Making It Interesting

Murray Davis published a now classic article on what causes some kinds of information to be judged interesting while other information is uninteresting.10 The veracity of the information has little to do with that judgment, according to Davis. Rather, the degree to which information is interesting depends on the extent to which it contradicts weakly held assumptions and challenges the status quo. If new information is consistent with what is already known, people tend to dismiss it as common sense—it is not interesting. If new information is obviously contradictory to strongly held assumptions, or if it blatantly challenges the core values of the organization’s members, it is labeled ridiculous, silly, or blasphemous—and it is also dismissed as not interesting. What is considered interesting is information that helps create new ways to view the future, challenges the current state of things but not core values, and lifts people’s thinking into new realms of what is possible. Interesting information draws people in and creates new insights or uncovers a new way to think.

Visions of abundance are interesting. They contain challenges and prods that confront and alter the ways people think about the past and the future. They are not extreme or threatening in their message, just provocative. Visions such as “a man on the moon by the end of the decade” (President John F. Kennedy), “corporate immortality” (Ralph Peterson, CEO of CH2M HILL), “perfect service” (Mike McCallister, CEO of Humana), and “one person, one computer” (Steve Jobs, founder and CEO of Apple) were all visions that challenged the status quo, but not in outlandish ways. They identified a message that people cared about but which challenged the normal perception of things. The fact that their messages are interesting is what captured attention and positive energy.

Activity

Vision of Abundance

Think of inspiring vision statements you have encountered. Examples might include Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech (http://historywired.si.edu/detail.cfm?ID=501), Nelson Mandela’s “An Ideal for Which I Am Prepared to Die” speech (http://db.nelsonmandela.org/speeches/pub_view.asp?pg=item&itemID=NMS010&txtstr=1963), or Winston Churchill’s “Never Give In” speech (http://www.winstonchurchill.org/learn/speeches/speeches-of-winston-churchill/103-never-give-in). Write a simple paragraph articulating your own vision of abundance. This can be for your organization or for yourself. Make certain that you include at least one story, metaphor, or image. This is not a statement of goal setting or problem solving; rather, it is a statement that leads to abundance. Address this question: “Based on what we/I care most deeply about, what is the highest and most inspiring aspiration we/I can achieve?”

Consider the example of a vision articulated by John Scully, who took over for Steve Jobs in the very early days of Apple Computer’s existence in 1987. It provides just one example of abundance:

We are all part of a journey to create an extraordinary corporation. The things we intend to do in the years ahead have never been done before.… One person, one computer is still our dream.… We want to make personal computers a way of life in work, education, and the home. Apple people are paradigm shifters.… We want to be the catalyst for discovering new ways for people to do things.… Apple’s way starts with a passion to create awesome products with a lot of distinctive value built in.… We have chosen directions for Apple that will lead us to wonderful ideas we haven’t as yet dreamed.11

GENERATING COMMITMENT

Once the vision of abundance has been articulated, positive leaders must help organization members become committed to the vision—to adopt the vision as their own and to work toward its accomplishment. The whole intent of a vision statement is to mobilize the energy and potential of the individuals who are to implement it and who will be affected by it. Developing a culture of abundance depends on commitment to a vision of abundance.

Identify Small Wins

We are all more committed to winners than to losers. Fans attend more games when the team has a good record than when it has a poor record. The number of people claiming to have voted for a winning candidate always exceeds by a large margin the actual number of votes received. In other words, when we see success or progress being made, we are more committed to respond positively, to continue that path, and to offer our support.12

Leaders of positive culture change create this kind of commitment by identifying and publicizing small wins. These can be things as minor as a new coat of paint, abolishing reserved parking spaces, adding a display case for awards, flying a flag, holding social events, instituting a suggestion system, and so on. A small wins strategy is designed to create a sense of progress and momentum by creating minor, quick changes. The basic rule of thumb for small wins is this: Find something that is easy to change. Change it. Publicize it, or recognize it publicly. Then find a second thing that is easy to change, and repeat the process.

Small wins create commitment because (1) they reduce the importance of any one change (“It’s no big deal to make this change”), (2) they reduce demands on any group or individual (“There’s not a lot we have to do”), (3) they improve the confidence of participants (“I can do that”), (4) they help avoid resistance or retaliation (“Even if I disagree, it’s only a small thing”), (5) they attract allies and create a bandwagon effect (“I want to be associated with this success”), (6) they create the image of progress (“Things seem to be moving forward”), (7) if they do not work there are no long-lasting effects (“If it doesn’t pan out, there’s no major harm done”), and (8) they provide initiatives in multiple arenas, reducing the chance of resistance forming in one (“I can’t say no to all of them”).

Demonstrating Public Commitment

Making a public declaration motivates individuals to do what they have said they will do.13 After making public pronouncements, individuals are much more committed to and more consistent in the behavior they have espoused.14

For example, during World War II, good cuts of meat were in short supply in the United States. Kurt Lewin found that a significant difference existed between the commitment level of shoppers who promised out loud to buy more plentiful but less desirable cuts of meat (e.g., liver, kidneys, brains) compared to those who made the same promise in private. In another study, students in a college class were divided into two groups. All students set goals for how much they would read and what kinds of scores they would get on exams. Only half the students were allowed to state these goals publicly to the rest of the class. By midsemester, the students who stated their goals publicly averaged an 86 percent improvement. The students who only set their goals privately averaged a 14 percent improvement.15

Leaders creating a culture of abundance look for opportunities to have others make public statements in favor of the vision or to restate the vision themselves. Assigning individuals to explain the vision to the public, to outside groups, to other employees, or to family members provides opportunities for them to put the vision in their own words. Discussion groups that encourage members to refine or clarify the vision also provide opportunities for public commitment.

Activity

Generating Commitment

As you consider your desired culture of abundance, identify two or three small things that can be easily and readily changed and that will make progress toward that culture—what could be altered beginning Monday morning? What has been accomplished so far—what minor victories can you highlight, and how can you publicize them? What opportunities can you provide for people to publicly express their commitment? Take a few minutes to identify one or two ideas for creating small wins and for generating commitment.

FOSTERING SUSTAINABILITY

The fifth step in the culture change process is intended to push culture change deeper into the organization, ensuring that that culture of abundance becomes institutionalized and can be sustained over time. Culture change will be sustainable when the change extends beyond merely surface-level behavior, and values, ideology, and preferences change at a fundamental level. The United States Army refers to this step as “creating irreversible momentum,” ensuring that positive change is institutionalized so strongly that it cannot be thwarted. The challenge is to separate the vision from the visionary—to get all members of the organization to own and become champions of the change, and to create processes that reinforce the positive change without having to continually rely on the leader. Even if the leader leaves, the positive change will continue because sustainable momentum is in place.

Fostering sustainability does not happen quickly, of course, and the four previous steps in developing a culture of abundance—creating readiness, overcoming resistance, articulating a vision, and generating commitment—must be successfully accomplished first. Sustainability is the final step to ensure that a cultural change will actually occur over time, since culture does not change quickly.

Metrics, Measures, and Milestones

Metrics (specific indicators of success), measures (methods for assessing levels of success), and milestones (benchmarks to determine when detectable progress has occurred) are key to ensuring that change is sustainable. These three factors help guarantee accountability for change, make it clear how much progress is being made, and provide visible indicators that the change is successful. The adage “You get what you measure” is an illustration of this principle. Change becomes sustainable when it is part of what people are held accountable to achieve. Sustaining positive change, then, means that clear metrics are identified, a measurement system is put into place, and a milestone is specified for when the change has been accomplished.

Stories

Culture change is more likely to be sustainable if it is carried and communicated through stories. Just as right-brain elements must be a part of vision statements, culture change must rely on stories to be sustainable.16 The key values, desired orientations, and behavioral principles that are to characterize the new culture are usually more clearly communicated through stories than in any other way. The values and virtues that employees are to exemplify in the new culture are best explained and demonstrated by telling and retelling stories that illustrate the desired behaviors. Ideal stories draw on real experiences, show personal involvement, and illustrate the key attributes of the culture of abundance. The stories do not need to be numerous; just one or two may be sufficient to communicate the desired culture of abundance.

Social Support

People are in most need of social support when they are in the middle of change and uncertainty.17 Culture change is a time when supportive interpersonal relationships are especially critical. Therefore, social events, gatherings, and collective activities are important for fostering sustainability. Building coalitions of supporters and empowering them to communicate and demonstrate key cultural values are also helpful. Especially, identifying and engaging positive energizers and those who will be most affected by the changes deserves special attention. Champions who can influence the opinions of others and serve as role models for the virtues and values associated with an abundance culture must be visible and active.

Leadership

Positive leaders must have the skills to create the consensus and collaboration required for any organization to sustain change. Positive leaders must also develop the competencies necessary to sustain the organization once it has actually developed the desired culture of abundance. They must both lead the change process and be able to reinforce and support the changes that have occurred.

Leaders also must demonstrate personal commitment to and responsibility for the change. One way to do this is to make a visible “sacrifice”—that is, publicly give up something of value (financial, symbolic, or structural) that is associated with the current culture in favor of something that embodies the values and virtues of the new culture. A visible personal sacrifice by the leader not only demonstrates personal responsibility for the change but communicates authenticity, sincerity, and a genuine devotion to the new culture.

Activity

Fostering Sustainability

Consider the following questions that can help ensure sustainable culture change in your organization:

Metrics: What are the key indicators of culture change? How do we know culture change is occurring? What are the indicators of progress toward culture change?

Measures: How will we gather information about our new culture? What will we assess?

Milestones: When will we expect to see noticeable culture change?

Stories: What incidents or events illustrate the key virtues, values, and attributes that will characterize our new culture of abundance? When have we demonstrated this kind of culture in the past?

Social support: In what ways can we bring people together? How can involvement and consensus be facilitated? What can we do to foster stronger social relationships? Who needs to come together to champion the culture change?

Leadership: Where are we strong, and where are we in need of leadership development? What leadership development activities should we sponsor to help leaders build the needed competencies and behaviors? What meaningful and visible sacrifice could be made?

CONCLUSION

Organizations that flourish have developed a culture of abundance, one that both allows its members to flourish personally and makes it possible for the organization to achieve extraordinarily positive performance. The steps described here are not comprehensive, of course, nor do they represent the only possible path toward a culture of abundance. Other models of change and many more suggestions for culture change are available.18 On the other hand, both empirical evidence and multiple intervention experiences in organizations have confirmed that the tools outlined here are an effective way to help develop a culture of abundance in organizations.