6

HOW TO APPLY POSITIVE

LEADERSHIP IN ORGANIZATIONS

Practicing positive leadership involves more than the personal pursuit of excellence or the demonstration of individual capabilities. The organizational context must be taken into account, and organizational behavior entails much more complexity than does individual behavior. Organizations have multiple constituencies that must be addressed; processes, routines, and structures that have to be considered; and cultures, embedded values, and traditions that need to be respected. Employee preferences and relationships must be taken into account, and competitors and customers must be acknowledged. Given all these demands, it is helpful to have a framework to help you identify priorities and trade-offs in applying positive leadership practices in organizational settings.

The framework we will use is called the Competing Values Framework. It was developed 30 years ago as my colleagues and I were studying what makes organizations effective. This framework has become among the most utilized in the world to analyze organizational challenges and lead improvement. It highlights the trade-offs and tensions that exist in every high performing organization.

In this chapter, the framework is used to identify four issues that must be dealt with in every organization—focusing on customers, empowering employees, creating new ideas and innovations, and fostering efficiency. We will explore one positive leadership practice associated with each of these four issues.

These practices will help leaders who face criticism that positive leadership is synonymous with easy-going, smiley-faced, touchy-feely practices. Using the Competing Values Framework will expand their leadership repertoire and produce positive results that are not synonymous with mere softness or sweetness.

POSITIVE LEADERSHIP IN ORGANIZATIONS

As pointed out before, there is abundant empirical evidence that practicing positive leadership produces desirable outcomes in organizations. Studies from the Center for Positive Organizations at the University of Michigan demonstrate that practicing positive leadership in organizations across multiple industries—financial services, health care, military organizations, government agencies, transportation, manufacturing, education, airlines, pharmaceuticals, and families—leads to improved performance. Profitability, productivity, quality, innovation, customer loyalty, and employee engagement all improve.1 One particularly powerful illustration of the effects of positive leadership comes from Jim Mallozzi, a former CEO and senior executive in the financial services industry. In one business, Jim was charged with leading the merger of two very large financial services organizations.

We were trying to merge the two cultures together, and in the beginning it was like trying to merge the Red Sox and the Yankees; we had two distinct cultures—one from New England and the other one from the New York/New Jersey area. Both were very strong, very passionate, and very powerful. As you can imagine, trying to put these two cultures together was a challenge.2

Over a two-year period, Jim and his colleagues systematically implemented positive leadership practices in the company. They began with senior executive retreats, training and development experiences for leaders across departments and functions, and cascading activities that embedded positive leadership practices among all levels of the merged organization.

It was a conscious two-year effort that involved not only the senior leadership who led from the front, but virtually everybody in the entire organization needed to be part of it. It was fun to see all the different groups put their own little twist on positive leadership. There were a variety of tools and techniques that we implemented.… The primary outcome was the assimilation of the two companies. We kept 95 percent of our clients. Our annual employee satisfaction scores and employee opinion survey results increased. We had less voluntary turnover, and the earnings of the company started going up at about 20 percent per annum on a compound rate. It was a real success story. In addition, when the president left to take a job in a different company, the culture and the practices actually stayed in place.3

In Jim’s next assignment, as CEO of another firm, losses amounted to $140 million the year before he arrived and were projected to be $70 million for the current year.

I harkened back to my previous experience and what I learned about positive leadership.… We started with a variety of exercises to show that when you start with the positive, when you ask people to genuinely help you achieve what you’re trying to do, fabulous things can happen … it really was a case of setting an example in a very public way.… As I said, when I took over, the company wasn’t doing very well. We had lost a lot of money. Well, sure enough, we went from a $70 million loss to a $20 million profit, and we actually achieved two times our expected business plan. We doubled our profits from what we’d expected. Our employee satisfaction scores went up in nine out of twelve categories.4

A FRAMEWORK FOR ORGANIZING

POSITIVE PRACTICES

So what was Jim’s secret? How did he achieve such extraordinary results in two large, complex financial services organizations? One valuable tool for him was the Competing Values Framework, which helped him organize his priorities and actions.5

In brief, the Competing Values Framework is based on two dimensions. Specifically, some organizations and some managers are effective if they are stable, efficient, and predictable. Others are effective if they are flexible, dynamic, and creative. These two competing orientations—stability versus flexibility—represent the vertical axis of the framework. In addition, some organizations and some managers are effective if they create integration, unity, and smoothly flowing internal processes. Others are effective if they are competitive, generate independence, and focus on external constituencies. These two competing orientations—internal focus versus external focus—represent the horizontal axis of the framework. Four quadrants are produced by these two dimensions (see Figure 15).

The quadrants of the Competing Values Framework have been found to be very robust, accurately describing a wide variety of individual phenomena (including cognitive processes, information processing, neurological drives, leadership styles, and managerial competencies) as well as organizational phenomena (including culture, structure, quality processes, human resource management practices, and competitive strategy).6 We have conducted about three decades of research on this framework, and it is now used by tens of thousands of organizations worldwide. Most important for our purposes is that these quadrants help organize the major practices that positive leaders can implement to achieve positive performance in organizations.

FIGURE 15

The Competing Values Framework

To be effective, leaders must maintain efficient, predictable, and well-oiled organizational processes. This represents the Hierarchy quadrant with its emphasis on maintaining control. Too much emphasis on stability and control, however, creates a frozen bureaucracy, so leaders must also pay attention to the competing quadrant with its emphasis on creativity—the Adhocracy quadrant. Change, flexibility, and dynamic innovation are also important for effective positive leadership. An overemphasis on creativity and change, however, leads to expensive program-of-the-month dynamics.

Similarly, effective leaders must engender teamwork, cohesion, and cooperative interpersonal relationships—a focus of the Clan quadrant, with its emphasis on collaboration. On the other hand, an overemphasis on these dynamics ignores the need for immediate results, fast action, competition, and attention to external customers.7 The Market quadrant helps balance out the soft approach to leadership with a focus on competition and immediate results. Here, though, an overemphasis on competition leads to an oppressive sweatshop atmosphere. Because of the problems that result from overemphasizing one of the quadrants at the expense of the others, the Competing Values Framework highlights the need to apply positive leadership practices in each quadrant.

One criticism of positive leadership, for example, is that it over-emphasizes soft, touchy-feely, smiley-face, saccharine-sweet, team-focused, cohesive activity. The hard-nosed, competitive, and challenging aspects of leadership are ignored. This criticism is legitimate if positive leadership is limited only to Clan Quadrant practices, but the Competing Values Framework helps remind and guide leaders to be more well-rounded in their implementation.

Not all positive leadership practices can be reliably categorized into one of the four Competing Values Framework quadrants, of course, but many positive practices can be. And this framework can help positive leaders identify which practices are most relevant for their own organizational settings. The framework was one of the key tools used by Jim Mallozzi in guiding his positive leadership turnarounds.

Specifically, Jim organized a change team consisting of positive energizers to disseminate positive leadership practices throughout his organization (see Chapter 3).

They were able to introduce more positive leadership concepts—which in this case was the Competing Values Framework—and it was even more well-received than the initial introduction of positive leadership to the top officers. The team introduced the competing values framework rapidly into our organization. They have now created their own self-sustaining effort in continuing to bring the practices of positive leadership into our organization. It has been fabulous to see.8

EXAMPLES OF POSITIVE LEADERSHIP PRACTICES IN

EACH QUADRANT

While it is not possible to identify a comprehensive list of positive practices across all four quadrants, of course, Figure 15 highlights one exemplary practice in each quadrant.

Market Quadrant: Customer Loyalty

Every organization has customers—defined as those who receive or are affected by the product or service being delivered. Customers can be internal, that is, members of the organization itself, or external, outside the organization. Most organizations are well aware of the need to satisfy their customers. The American Customer Satisfaction Index is a well-known instrument for identifying the extent to which customers are satisfied with various organizations and industries.9 Customer satisfaction scores have been found to be a good predictor of company return on investment, net cash flow, and stock returns.10

Customer loyalty, however, is different from customer satisfaction. Essentially, loyal customers are those that are unlikely to leave, will repurchase goods and services, and will recommend the product or service to others.11 Loyal customers’ commitment to the organization is much greater than the commitment of merely satisfied customers.

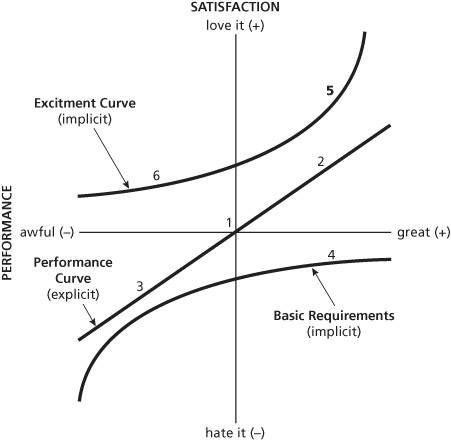

One practical tool for enhancing customer loyalty is based on the Kano model (see Figure 16).12 This model specifies two dimensions—a satisfaction dimension (“I love it” [+] or “I hate it” [−]) and a performance dimension (“Performance is great” [+] or “Performance is awful” [−]).

To illustrate, let us assume that you are in the market for a new automobile, and you visit a dealership to purchase the car. You specify for the salesperson the model you want and the features that you prefer—say, four doors, power package, good gas mileage, and black color. If the salesperson shows you this exact car with these precise features—exactly what you request—your position on the Kano model chart is right in the center of the performance curve (point 1). This curve is based on features that the customer asks for directly. In this case, you are perfectly satisfied—not ecstatic and not disappointed—because the car’s performance matches your spoken expectations. If, however, you discover that the car handles much better, is quieter, and has a more powerful engine than you expected—that is, the car’s performance exceeds your expectations—your position on the performance curve moves up (point 2). You are more satisfied.

If, however, you find that the car has no carpet, no gear shift knob, and no wiper blades, you will probably not want to buy the car. But you would likely never explicitly ask the salesperson for a car with carpet, a gear shift knob, and wiper blades. Those are just basic requirements. If they are not present, dissatisfaction is high (point 3). However, if the salesperson gives you an Elvis Presley rhinestone-studded gear shift knob, it is unlikely to increase your satisfaction. That is, a great deal of money can be spent trying to improve the performance of basic requirements, but satisfaction is not improved at all. There are some things that must be present, but if they are extraordinary, it does not matter (point 4). Improvement in basic requirements has little payoff after they meet essential needs.

On the other hand, if you find that the car has a voice-activated GPS system, a backup camera with an automatic braking feature, a remote entry and start feature, and free service during the 100,000-mile warranty period—that is, it possesses features that you did not expect and did not request, but which address issues that solve problems for you—your position on the Kano model chart is at point 5. This is the excitement curve. It produces customer loyalty, not merely customer satisfaction. If these features are not present, you are not dissatisfied (point 6). But their unexpected presence produces allegiance to the dealership, the likelihood of future purchases, and increased recommendations to others. Companies can expect a 400 percent increase in revenues when they get customers on the excitement curve.13 The principle is: Solve a problem for a customer that he or she did not expect to be solved and did not request. This represents positively deviant performance and produces customer loyalty.

One caveat in the model is that, over time, excitement factors become basic requirements. Customers come to expect the features that at one time were surprises and delights. This means that the challenge of finding ways to surprise and delight customers, to solve their problems, by identifying features on the excitement curve is never finished.

Consider your areas of responsibility in your organization. Think of both internal and external customers. Select your key customer for this activity. Identify the value you provide in three areas:

1. Basic curve: value you must deliver (implicit)

2. Performance curve: value you should deliver (explicit)

3. Excitement curve: value you could deliver (implicit)

Take these factors into account:

• What does your customer expect from you?

• What problems does your customer face that neither you nor anyone else is expected to solve?

• What excitement factors could you deliver to engender customer loyalty?

Clan Quadrant: Empowerment

A positive leadership practice associated with the Clan quadrant is the empowerment of employees. It is important to point out that while empowerment and power are often confused, they are not the same thing. Power always comes from an external source—it can be bestowed on someone—and is defined as the capacity to get someone else to do what you want them to do. Empowerment, on the other, comes from an internal source—it must be personally accepted—and is defined as the capacity to get others to do what they themselves want to do.14 The leadership challenge, therefore, is to ensure that what others want matches what is best for the organization.

A great deal of research confirms that empowered employees are more productive, more satisfied, and more innovative than unempowered employees.15 Organizational performance is significantly greater when empowerment scores are high among employees, and neither managers nor organizations can experience long-term, sustained effectiveness without a sense of empowerment.16

Based on the research of Gretchen Spreitzer and Aneil Mishra, empowerment is likely to be produced when five factors or dimensions are present.17 Each of these five dimensions is necessary, so if any one is absent, empowerment will not occur.

The Five Dimensions of Empowerment

Dimension |

Explanation |

Self-efficacy |

A sense of personal competence |

Self-determination |

A sense of personal choice |

Personal consequence |

A sense of having impact |

Meaning |

A sense of value in activity |

Trust |

A sense of security |

Self-efficacy: Empowered people feel confident and competent. They have a sense that they have the skills, abilities, knowledge, and resources to successfully accomplish the tasks with which they are faced, and that they have relationships with others that provide support.

Self-determination: Empowered people sense that they have choice and alternatives. They have discretion and options available so they can pursue what they desire, use the methods of their choice, and therefore they can take responsibility for the outcomes they produce.

Personal consequence: Empowered people are aware of the consequences of their actions. They see the effects of their actions on customers and on broader organizational goals, and they receive feedback on their contribution to those outcomes.

Meaning: Empowered people see the meaningfulness of the activities in which they are engaged. They have a conviction that what they do is attached to a core principle, to something they care about, to something worthy of their time and effort—something that can create a legacy.

Trust: Empowered people have a sense of security. They have confidence that they will hear and can speak the truth, that they will not be harmed or personally maligned, and that they will be treated fairly.

Below are several suggestions for facilitating empowerment across these five dimensions, many of which have emerged from empirical research. Of course, this is not a comprehensive list, and the suggestions are provided here primarily as thought starters. For example, self-efficacy can be fostered by providing personal mastery experiences—breaking apart large tasks and assigning one part at a time, or assigning simple tasks before difficult tasks, or highlighting and celebrating small wins.18

Facilitating Empowerment

SELF-EFFICACY (A SENSE OF PERSONAL COMPETENCE)

• Provide personal mastery experiences

• Connect actions to successful outcomes and effects

• Model successful behaviors

SELF-DETERMINATION (A SENSE OF PERSONAL CHOICE)

• Clarify the overriding vision and goals, not actions

• Provide information

• Point out more than one alternative

PERSONAL CONSEQUENCE (A SENSE OF IMPACT)

• Connect with recipients of the outcomes

• Provide resources (time, space, equipment, authority)

• Recognize, encourage, and celebrate successes

MEANING (A SENSE OF VALUE IN THE ACTIVITY)

• Clarify long-term consequences

• Highlight virtuousness and values linked to the activity

• Connect to admired role models and exemplary successes

TRUST (A SENSE OF SECURITY)

• Provide honest feedback using supportive communication

• Offer support for development and growth opportunities

• Exhibit consistency, fairness, and openness

Answer these two questions: (1) What can I do to enhance my own empowerment? (2) What can I do to help create an empowering environment? The first question relates to your own circumstances at work. The other relates to the way in which you can contribute to others.

Share your ideas with colleagues. Ask your colleagues to add at least one new suggestion to your answers for each of the five dimensions of empowerment.

Adhocracy Quadrant:

Generalized Reciprocity

Positive leadership practices that focus on the Adhocracy quadrant are designed, among other things, to enhance innovation and creativity and to uncover unrecognized resources in the organization. One positive practice relies on generalized reciprocity.19 Generalized reciprocity occurs when a person contributes something that is not directly connected to the receipt of something personally beneficial. The contribution occurs because it will be good for someone else.

When Jim Mallozzi had his first meeting as CEO with 2,500 sales personnel in a large auditorium, he asked participants to take out their iPhones and Black-Berrys and text or email one great idea to a special company address for how to get a new client, how to close a sale, or how to keep a customer for life. More than 2,200 ideas were shared, and Mallozzi reported that a number of these ideas were still being actively used fifteen months later.

Generalized reciprocity occurs when one person provides benefit to someone else—such as giving a gift or sharing an idea—without keeping track of its value and without expecting anything in return. The assumption is that the value provided will balance out over time as others provide benefits to their associates.

A positive practice that helps organizations identify new ideas and previously unrecognized resources relies on this principle of generalized reciprocity. Introduced by Wayne Baker, a professor at the University of Michigan, the practice is designed to construct a reciprocity network (see www.humaxnetworks.com).20 Baker found that constructing reciprocity networks in five different organizations produced more than three-quarters of a million dollars in value and saved almost eight thousand hours.21

Reciprocity networks are created among individuals in an organization—even a temporary organization such as a class or a gathering—by having individuals identify needs or requests and then having others in the organization respond to those needs or requests with resources or contacts.

Building a reciprocity network can be done with four steps:

1. Write on a whiteboard or flip chart the names of each of the people in the organization, group, or gathering.

2. Each of those people writes down a specific request, need, or issue with which he or she needs help. These issues may be personal or work-related. The requests must be SMART—that is, they must have the following characteristics:

S = Specific: a resource or resolution to the request must be available

M = Meaningful: the request is not trivial or irrelevant but refers to something important

A = Action-oriented: there must be action that can be taken in response to the request

R = Real need: the request must be tied to a genuine need

T = Time-bound: a time frame is given for when a response to the request is needed

Examples of work-related requests might be: “I need to fill a vacancy in the accounting department with a CPA this month,” “I need a new IT software system to streamline our inventory control,” “I need to become more recognized as a potential leader in my organization,” or “I need to determine how to downsize my unit by 15 percent.”

The individual verbally describes the request to his or her colleagues and posts it below, or next to, his or her name. An easy way to do this is to write the request on a Post-it note.

3. Each colleague identifies the resources (knowledge, information, expertise, budget, product, emotional support, and so on) or contacts (someone he or she knows who can provide the resource) in response to as many requests as possible. These contributions are written on a Post-it along with his or her name so that follow-up connections can be made. Each response is posted below the relevant request. Then, in public, each person takes the time to verbally share his or her contributions to the requests for which he or she can add value. Sharing aloud these contributions tends to stimulate the thinking of others who may also realize some additional resource or contribution.

4. After each person has had a chance to explain aloud his or her contributions, provide time for the people who made the requests to connect with each colleague who offered resources or contacts.

An important outcome of this practice is to uncover new ideas and new resources that were previously unknown or unrecognized. Baker found that individuals who offer the most contributions tend to be rated as more competent leaders, more interpersonally effective, and higher performers in their organizations than others.22 That is, people who are willing to demonstrate generalized reciprocity—to contribute without expecting a personal benefit in return—tend to be more successful as positive leaders.

In your organization, team, or gathering, or even in your family, follow the steps of the reciprocity network exercise. Ask each member to make a request, offer contributions, and connect with newly uncovered resources.

A Process for Building Reciprocity Networks

1. Make a request (identify a need or specify a problem), post it, and explain it briefly.

2. Determine in what ways you might be able to help with what others have requested. What resources do you possess or know about? How might you add value? Post and explain your contributions.

3. Allow time for requesters and providers of resources and contacts to connect.

Hierarchy Quadrant:

Eliminate Inefficiencies

The Hierarchy quadrant, with its emphasis on control, sometimes possesses a negative connotation, since bureaucracy, red tape, and micromanagement are often linked to this quadrant. Positive leaders, however, are cognizant of organizations’ need for measurement, accountability, and efficiency, which help balance out the Adhocracy quadrant’s emphasis on vision, creativity, new resources, and new ideas.

Although a large number of practices are available for ensuring accountability, efficiency, measurement, and control, only one is briefly discussed here. It emerged from studies of organizational downsizing in which organizations sought to increase efficiency and control by eliminating jobs and headcount.23 Downsizing is the single most implemented organizational change strategy in the world, but it is frequently unsuccessful in achieving the desired results. Inefficiency, increased costs, and deteriorating quality are often the consequences.24

One major reason for these negative results was highlighted by an executive whose firm had experienced several rounds of downsizing:

The most cost savings in our organization can be generated by improving coordination, collaboration, trust, communication, and information sharing. Most of our costs reside in these soft factors. Yet these costs are not systematically measured. We really have no process for keeping track of, or for managing, our actual costs. We don’t even really know what our true costs are given these soft factors. Unless we take a very different approach than we have in the past, our downsizing efforts will again be misplaced and will never really be effective.25

Inefficiencies and lack of control in organizations—often called “organizational fat”—frequently remain un-monitored, unmeasured, and even unrecognized. They add costs, create waste, and foster disorganization. Here are a number of examples:

Data Fat: excess programs, unusable information, hard to find data

Idea Fat: suggestions that are never implemented, excessive discussions, dogmatic perspectives

Procedure Fat: excessive audits, documentation, permissions, meetings, paperwork

Career Fat: self-aggrandizement, self-centeredness, lack of teamwork

Belief Fat: uninformed opinions, excess disagreement, recalcitrant positions

Training Fat: unused, irrelevant, or in effective training; no application or follow-up

Supervision Fat: too many administrators, lack of empowerment, centralized decisions

Time Fat: repetition, redundancy, lack of responsiveness, missed deadlines

Learning Fat: redundant first-time learning, excessive re-learning, off-target learning

Launch Fat: new programs, initiatives, or entrepreneurial activity that are launched but not sustained

Leadership Fat: de-energizing, non-empowering, lack of vision, politicized decisions

Activity

Hierarchy Quadrant

Consider the organization in which you are now working. Identify the major sources of organizational fat. What is not properly controlled? What causes inefficiency and waste? Use the list above, but include other sources particular to your organization. Identify one action that you might take or suggest to trim at least one source of fat.

CONCLUSION

Positive leaders must take into account the specific organizational context in which they find themselves, because practices and tools are not universally applicable in every situation. The organization’s customers, processes, routines, employees, and culture all help dictate how effective positive leadership can be practiced. The Competing Value Framework can guide the selection of appropriate positive leadership practices that help address the competing demands in organizations.