3

HOW TO DEVELOP POSITIVE ENERGY NETWORKS

At the heart of positive leadership lies the concept of positive energy. Whereas much popular literature is dominated by discussions about the toll of stress, burnout, depression, tension, anxiety, fatigue, disengagement, and fear, less attention is paid to positive energy, even though it is one of the most powerful and important predictors of organizational and individual success. It is almost impossible to be a positive leader without also being a source of positive energy.

This chapter summarizes evidence that positively energizing leaders create extraordinarily high performance in their organizations and in their people. It provides some tools and practices that have been successfully applied in a variety of settings, such as those associated with recreational work, contributions, and mapping energy networks.

Positive energy is characterized by a feeling of aliveness, arousal, vitality, and zest. It is the life-giving force that allows us to perform, to create, and to persist. It unlocks resources and capacity within us and actually increases our ability to flourish.1 Positive energy is probably the single most important attribute of positive leaders.

TYPES OF ENERGY

To learn how to foster positive energy, we have to distinguish among several familiar but different types of energy: physical, psychological, and emotional.

In the human body, physical energy is associated with the interaction between glucose, the substance that provides the energy for our cells, and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a molecule our cells produce that captures that energy and delivers it to where it is needed.2 Activity, whether it is running a marathon or merely working a long, difficult day, depletes the body of these substances, and we have to restore them through nourishment, relaxation, and sleep.

Psychological energy is associated with mental concentration and cognitive focus. When intense mental effort is expended—as when studying for an exam or engaging in extended concentration on a challenging problem—we become mentally fatigued. Most of us have experienced being so tired that it is difficult even to think. Psychological energy is replenished by mental breaks, relaxation, and by changing the focus of attention to something less tedious.

Emotional energy is associated with the experience of intense feelings. As with physical and psychological energy, emotional energy can be depleted—for example, by impassioned excitement in an athletic contest, intense sadness at the loss of a family member, or the breakup of a relationship—and must then be replenished. Burnout is an example of emotional exhaustion, and like other forms of energy, we need recuperation to replenish and restore this form of energy.

In contrast to these three types of energy, which become depleted when used, relational energy actually increases as it is exercised. Expressing and receiving relational energy through positive interpersonal relationships uplifts, invigorates, and rejuvenates us. It increases rather than diminishes as it is expended. Consider the times you have interacted with a person with whom you have a loving, supportive relationship. Your energy is not diminished or exhausted as a result of the interaction; rather it is renewed and augmented. Experiencing love, nurturing, and support is life-giving rather than life-depleting.

The question this chapter addresses is how leaders of organizations can utilize this positive relational energy and enable others to use it as well.

ENERGY AND MOTIVATION

At first glance, you might think that positive energy is the same thing as mere motivation. A common assumption is that the key challenge of a leader is to motivate others, and indeed there is a large literature on motivation and incentives. However, motivation and energy are not synonymous. Theories of motivation seldom acknowledge energy as the driving force behind action and performance. Instead, they usually assume that people are motivated by need fulfillment, by goals, or by cognitive evaluations.

For example, one set of motivation theories suggests that people are motivated by unfulfilled needs. These needs include existence needs, such as personal safety and physiological needs; relatedness or social needs, such as belonging, affiliation, or self-esteem needs; and growth needs, such as self-actualization and meaning needs.3 Other authors have postulated that the need for power and the need for achievement are the bases of motivation.4 In these theories, an unfulfilled need serves as a motivator. (The exception is self-actualization or growth needs, in which fulfilled needs lead to more motivation.)

Another set of theories suggests that the presence of goals serves to motivate performance. People are motivated by having a clear target or objective that guides task accomplishment. These theories draw on the assumption that if we want high performance, we almost always establish goals as a way to attain it. Goals give people something to strive for.5

A third set of motivation theories, called expectancy theories, suggest that people make cognitive evaluations regarding the circumstances they encounter and are motivated to act based on their appraisal of those circumstances. Specifically, if we have the ability (meaning the aptitude, training, and resources) to succeed, if we have the expectation that by expending effort we can succeed, and if we feel that the task is worthwhile or that it is important, we will be motivated. Cognitive evaluation of each of these various factors is required—though it can be subconscious—for motivation to be present.6

Another example of a cognitive theory associated with motivation is the social comparison theory. Simply put, if I think that I am being treated fairly—for example, if my compensation is similar to that of colleagues doing the same job—I will be motivated. If someone else is being paid more than I for the same work, I will be demotivated.7

None of these motivation theories acknowledges energy as a key source of activation or of enhanced task performance. It is true that leaders and managers must ensure that employees’ needs are met—for example, ensuring a safe and pleasant working environment, ensuring satisfying team dynamics, and providing opportunities for challenge and growth. They must establish goals, targets, and benchmarks against which performance can be measured. They must ensure fair and equitable compensation. And they must make it possible for employees to see the outcomes of their work and experience them as worthwhile. That is, they must manage need fulfillment, goal setting, and people’s expectancies.

However, positive energy is an even more important factor in accounting for high performance. While much of the leadership literature equates leadership and influence (people who influence others are shown to be higher performers)8 and maintains that information is a key attribute of leaders (people who are more informed and knowledgeable than others tend to have higher performance), research has confirmed that positive energy is four times more important in predicting performance than either influence or information. Positive energy trumps most other factors in accounting for organizational success.

Beryl Health, a call center in Texas, is three to four times more profitable than the industry average and enjoys miniscule employee turnover rates. CEO Paul Spiegelman attributes the firm’s success to the development and reinforcement of positive energy in the company. He has appointed one of his senior corporate officers as “Queen of Fun and Growth,” and her role is to organize family fun days and holiday carnivals as well as to foster a climate of non-stop positively energizing interactions. The payoff for Beryl is customer loyalty, fast growth, and a “Best Places to Work” designation.9

THE IMPORTANCE OF ENERGY

My colleagues and I conducted studies in four large organizations with the purpose of assessing positive energy in unit leaders.10 Measuring positive energy is best achieved by asking individuals to assess the extent to which they are personally energized as a result of interacting with another person. As an example, I would rate the extent to which I feel energized and uplifted when I interact with you. Note that I am not rating the extent to which I think you are a positive energizer; rather, I am rating my own feelings and responses. This is a subtle but important distinction. Measuring energy is a personal assessment. I do not know if you are experiencing positive energy, only that I am. So when we measure energy, we ask people to rate their own energy level when interacting with other individuals.

In our study, we found that five items form a reliable and valid measure of positive energy, and you may want to use this scale to assess positive leadership energy in your own organization:

1. I feel invigorated when I interact with this person.

2. After interacting with this person I feel more energy to do my work.

3. I feel increased vitality when I interact with this person.

4. I would go to this person when I need to be “pepped up.”

5. After an exchange with this person I feel more stamina to do my work.

The findings from this study revealed that when individuals are exposed to a positively energizing leader in their workplace, they have significantly higher personal well-being, higher satisfaction with their jobs, higher engagement in their organization, higher job performance, and higher levels of family well-being than those without exposure to positively energizing leaders. Moreover, the organizational unit in which these people work has significantly more cohesion among employees, more orientation toward learning, more expression of experimentation and creativity, and higher levels of performance than units without an energizing leader.11 The impact of having an energizing leader at work, in other words, was found to be extremely strong.

These findings are consistent with the research of Cole, Bruch, and Vogel, who found that positive energy is strongly related to individual goal achievement, engagement, job satisfaction, and firm performance across five different countries.12 They are also reinforced by studies confirming that individuals who positively energize others are higher performers themselves.13

Moreover, positively energized people are more adaptive, more creative, suffer from fewer physical illnesses and accidents, and experience richer interpersonal relationships than others. People tend to avoid and limit their communication with de-energizers, whereas they are attracted to positive energizers.14

CHARACTERISTICS OF POSITIVE ENERGIZERS

It is important to note that being a positive energizer is not the same as being an extrovert, gregarious, charismatic, or perky. The correlation between the Big 5 personality attributes (which include the extraversionintroversion dimension) and positive energy, for example, is low and non-significant. Being the first to speak, the one who dominates airtime, or the social butterfly is not necessarily positively energizing for others. Rather, positive energy is associated with a set of behaviors that are mostly interactive and behavioral and which can be learned and developed.

Listed below are attributes identified by executives when describing positive energizers in their organizations. It is not a comprehensive list, of course, but note that each of these attributes can be cultivated.

Energizers |

De-energizers |

They help other people flourish. |

They mostly see roadblocks and obstacles. |

They are trustworthy and have integrity. |

They create problems. |

They are dependable. |

They do not allow others to be valued. |

They use abundance language. |

They are inflexible in their thinking. |

They are heedful and fully engaged. |

They do not show concern for others. |

They are genuine and authentic. |

They often do not follow through. |

They see opportunities. |

They are self-aggrandizing. |

They solve problems. |

They are mostly somber and solemn. |

They smile. |

They are superficial and inauthentic. |

They express gratitude and humility. |

They are frequently critical. |

The activities listed in the rest of the chapter do not address these attributes individually; rather, they are designed to address positive energy in general and help you foster more positive energy in yourself, as well as to utilize positive energy networks in your organization.

DEVELOPING POSITIVE ENERGY

Because positive energy is synonymous with relational energy, building and nurturing strong interpersonal relationships is a key to fostering and maintaining positive energy.

Value-Added Contributions

Strong interpersonal relationships are most easily built on a foundation of positive feedback rather than criticism. Rather than pointing out weaknesses and deficiencies, positive leaders highlight others’ strengths, capabilities, and contributions and enable others in the organization to do the same. This does not mean being inauthentic or oblivious to flaws, rather it means highlighting the unique expertise upon which others can build.

Activity

Value-Added Contributions

This activity provides an opportunity to identify personal strengths and the contributions of unit members as well as to help individuals unleash latent positive energy in your organization.

1. Feedback

Provide each member of your organization or unit with one blank card or piece of paper for each other member of the organization or unit. For example, if there are ten members of the unit, each member receives nine cards—one for each person in the unit minus him-or herself. For each member’s batch of cards, write the name of each of the other members of the unit on one of the cards. (You can put the name of the person giving the feedback at the bottom of each card, but this is optional.)

On one side of the card, address this issue for the person whose name is on the card: Here are the special contributions that you make to our unit. Here are the unique strengths and capabilities that you demonstrate. Here is what I value regarding you and your contribution.

On the reverse side of the card, address this issue for the same person: If we are to become extraordinary, exceed our aspirations, become the benchmark organization, and achieve positive deviance in our performance, here is what else we need from you. Here is the positive energy you can provide. Here are the contributions you can make.

2. Distribution

Once all the comments have been written down, distribute each card to the individual whose name is on the card. In a ten-person unit, each person should have nine cards. Read the cards with your name at the top, identify the themes and the key points in the feedback those cards contain, and write down your interpretation and response.

3. Interpretations

Write at least one paragraph summarizing your interpretations of the feedback from the first side of the card. Address these questions: What do others especially value about my leadership capabilities? In what ways have I made important and unique contributions? In what ways do I add value? What do others most admire about me? What are my unique strengths?

Write at least one more paragraph summarizing your interpretations of the feedback from the second side of the card. This paragraph should contain your view of the expectations others have for you in order to enhance performance. In what ways can I add positive energy to the unit? If we are to attain our highest potential, and if we are to achieve dramatic success, here is what I need to do. Here is how I can contribute more. Here is how I can capitalize on my strengths.

4. Public Commitments

Read the paragraphs you have written to the other members of the unit. Highlight your commitments for adding value, fostering positive energy, and enabling success. Especially make sure that you identify how you will maintain accountability for following through. Ask other members of the unit to help ensure that you fulfill the commitments you have made in public.

CONTEMPLATIVE PRACTICE

A second way to enhance personal positive energy is through contemplative practices. Now, before you dismiss this as a New Age detour from an otherwise scientifically based approach to positive leadership, consider some recent research that has examined the impact of contemplative practice, especially loving-kindness meditation, on positive energy, positive emotions, and positive relationships.15 Neuroscientists have recently discovered, for example, that the brain actually changes as the result of our thoughts and experiences (a phenomenon referred to as neuroplasticity). In one study, Fredrickson and colleagues conducted a controlled experiment in which some people engaged in six weeks of loving-kindness meditation—designed to help people develop more warmth and tenderness toward themselves and others—and a control group that did not.

Loving-kindness meditation is a well-developed contemplative practice that focuses on self-generated feelings of love, compassion, and goodwill toward oneself and others. Essentially, people contemplate their feelings of positive regard for people close to them and extend them outward to others not so close to them. Similar practices include keeping a “gratitude journal,” engaging in personal prayer, and pondering spiritual inspiration. These practices essentially put people in a virtuous condition in which they represent the best of the human condition on a recurring basis.

The results of Fredrickson’s research are compelling. Dramatic differences were noted in brain functioning, vagal tone (the strength of the heart-body connection that controls cardiovascular and immune responses), and social energy.16 Furthermore, other studies show that regular meditation diminishes stress-related cortisol, insomnia, symptoms of autoimmune illnesses, PMS, asthma, falling back into depression, general emotional distress, anxiety, and panic. Meditation tends to help control blood sugar in type 2 diabetics, increases detachment from negative reactions, enhances self-understanding, and increases general well-being. Links have also been uncovered with various infections and chronic conditions such as high blood pressure, obesity, cancer, and heart disease.17

Regular contemplative practices are linked to increases in gray matter in the areas of the brain that control learning, memory, emotional regulation, self-referential processing, and perspective taking. In other words, contemplative practice literally changes the physical structure of the brain. Self-awareness, empathy for the emotions of others, and the reduction of cortical thinning due to aging all are enhanced.18

In an important finding, researchers discovered a strong interactive relationship between loving-kindness meditation, positive social connections, vagal tone, and positive energy. Positive energy was enhanced when people engaged in loving-kindness meditation, even for short periods of time.19 Practicing loving-kindness meditation for just seven minutes per day for several weeks was found to markedly increase social connectedness and relational energy.20

Activity

Contemplative Practice

Designate some time each day (as little as three minutes to as much as thirty minutes) to engage in a contemplative practice.

Loving-kindness meditation, in brief, requires that you put yourself in a relaxed and quiet state, then focus on your feelings of love, warmth, and positive regard for those closest to you, such as family members. Eventually you extend these feelings outward to those who are less close to you, such as friends and acquaintances.

Alternatively, you can maintain a gratitude journal, recording on a daily basis the things for which you are most grateful and/or the good things that happened to you. You can also spend time contemplating the people to whom you are the closest and recalling the things you love and admire about them, the gifts they have given you, and the ways they give you joy. A third option is to engage in personal prayer, in which you acknowledge and thank God for blessings, strengths, talents, and opportunities. These and similar activities have been shown in controlled experiments to produce remarkably positive consequences, especially if you are consistent in practicing them.

FUN AND RECREATION

In a variety of experiments in Europe, researchers demonstrated how making normally routine activities fun markedly altered the behavior and energy of people. Several of these experiments are visually described at www.thefuntheory.com. For example, 66 percent more people took the stairs than the adjoining escalator after experimenters made the stairs look like a piano keyboard with sounds associated with each step. More than a hundred people recycled glass bottles in a container that provided video-game sounds when a bottle was deposited, compared to only two people using a normal container nearby. Over two and a half times more trash was deposited in a waste can that provided a sound simulating the deposit falling hundreds of feet followed by a boom than in a nearby ordinary waste can. The experimenters demonstrated that making routine activities fun provides a positive experience, engenders positive energy, and alters behavior for the better.

Positive energy and fun are connected.21 Engaging in fun or novel activities not only breaks up routine and boredom but also fosters and enables positive energy, especially when the fun is connected with interpersonal relationships.

You may have heard the truism “People are willing to pay for the privilege of working harder than they will work when they are paid.”22 Consider what happens around mid-November in Utah and Colorado when the first major snowfall graces the ski resorts. Work and school absenteeism skyrockets. People sacrifice a day’s pay, don their $400 skis, their $300 boots, and their $250 ski outfit, buy $80 in gasoline to drive to the nearest ski resort, pay $115 for a lift ticket, eat a $35 hot dog for lunch, and return at the end of the day completely exhausted—having paid for the privilege of working harder than they would work when they are paid.

The question is, why? Why do people spend money to exhaust themselves, endure uncomfortable environmental conditions, and put their bodies at risk when they would not accept the same amount of money to do those things at work? The answer is obvious: because it is fun, not work.

The attributes that make activities fun, however, can be as typical of work as they are of leisure:23

Goals are positive and clearly defined: Recreation is always associated with a goal—winning a game, shooting a low (or high) score, challenging a personal best, improving performance. It is fun to work toward a positive goal. By contrast, the goal of simply avoid losing is not positively energizing, and activity just for the sake of activity rarely lasts. Positive goals make activities fun.

Scorekeeping is objective and self-administered: In recreation, we always know the score. When we do not keep score, we soon lose interest. Even on playgrounds, unorganized activity almost always eventually finds itself organizing into a game where scorekeeping occurs. In athletic contests, when the scoreboard stops working or players lose track of who is ahead, the game usually stops.

Feedback is frequent: In almost all recreation, we know how we are doing at any given moment. That is why organized athletics is played in the presence of fans. Their feedback makes it fun. Home field advantage matters.

Personal choice exists: In recreation, we have the chance to modify our behavior at will. We are not constrained to a specific routine or process that cannot be modified. Being empowered to alter performance is positively energizing when we are doing fun things.

Rules are standard and stable: In recreation the rules are always clear. Out of bounds is always out of bounds. A goal is always a goal. Effort and difficulty do not determine the outcomes. In baseball, a spectacular catch still counts for only one out.

Competition is present: Competition can be against personal past performance or against others, but we always have more fun when we are tested against a standard. If you are an adult, playing ball against third graders is not fun for very long because it is not challenging or competitive.

Social interaction is fostered: Bowling leagues arise because bowling alone is no fun. People play golf in foursomes because playing alone does not provide much positive energy. Recreation and fun are almost always associated with the chance to socialize and interact.

Activity

Recreational Work

Here are a dozen suggestions for experiencing fun and enabling positive energy. Select one or two activities that appeal to you (or come up with your own) and commit to personally engage, or help your organization engage, in them this week.

• Play a game, any game.

• Redesign your work so that it contains attributes of recreation.

• Visit one place you have not visited before.

• Spend some time in the natural, non-built environment.

• Sing.

• Sponsor a social event (even lunch) to which several people are invited.

• Laugh with someone.

• Engage at least once in whole-body physical exercise.

• Learn one new thing.

• Write a gratitude message to one new person.

• Surprise someone with a gift.

ASSESSING POSITIVE ENERGY NETWORKS

One of the key questions about positive energy is how it can be measured. How do you know who are the positive energizers in your organization, and how can you influence the amount of positive energy available? Diagramming a positive energy network is one way to address this issue.

Most of us are familiar with network maps—for example, we see route maps in the back of airline magazines or in bus or subway stations. They show connections among cities or stations, with some being at the center or hub of the network and some being on the periphery. The same kind of network map can be constructed to identify positive energizers, only instead of cities or stations, people are the nodes, and the lines drawn between them represent their relationships. Energy networks help identify which people serve as hubs in the network and which people are on the periphery. The research is clear that positive energizers—or hubs in the network—are not only higher performers themselves but also help elevate others’ performance.24

Three options exist for assessing positive energy networks: statistical mapping, a bubble chart, and a pulse survey.

Statistical Mapping

The most rigorous and sophisticated way to create a positive energy network map is to use statistical software. UCINET, a software application designed to construct network maps, can be downloaded from the Web (www.analytictech.com), and it is not difficult to understand and apply.

To use the software, provide a list of organization (or unit) members to each person in the organization (or unit). Ask each person to use a seven-point scale to evaluate his or her interaction with each of the other persons on the list.

When I interact with _____ , what happens to my energy?

1 = I am very de-energized

2 = I am moderately de-energized

3 = I am slightly de-energized

4 = I am neither energized nor de-energized

5 = I am slightly positively energized

6 = I am moderately positively energized

7 = I am very positively energized

The numbers associated with each name are recorded in the UCINET software, producing an analysis such as the one shown in Figure 9. This particular network map includes only the names of people who received ratings of 6 or 7—in other words, people who were rated as positively energizing.

The connecting lines show how many organization members are positively energized when interacting with each person. The more connecting lines, the more central the person is in the positive energy network. The highest energizers appear in the center of the network diagram. (It is possible, of course, to also create a map identifying those who received scores of 1 or 2. These are the folks who are de-energizers and tend to suck the life out of other members of the organization.)

UCINET also produces a “density score” showing the percentage of possible energizing ties that are present. Of all possible energizing connections, how many actually exist? The greater the percentage of all possible energizing ties that exist, the more effective the organization. (By contrast, the greater the density of de-energizing ties, the less effective the organization.)

One use of energy networks was illustrated by Prudential Financial Corporation, in which employee “change teams” were created to help disseminate information and conduct training associated with a major culture change initiative. The change team members were selected on the basis of their position in the positive energy network, with the highest positive energizers picked for the team. As might be expected, by using a team of positive energizers, the culture change initiative was implemented much more effectively and much more rapidly than normal.

Activity

Network Mapping

Download the UCINET software from www.analytictech.com; instructions are available online. Distribute to each member of your organization (or unit) a list of all members’ names. (This can include a large or small number of people inasmuch as network maps have been created with hundreds of people. You will want to identify the organizational unit that is of most interest to you.)

Have each member of the organization respond to the following question regarding every other person:

When I interact with _____, what happens to my energy?

2 = I am moderately de-energized

3 = I am slightly de-energized

4 = I am neither energized nor de-energized

5 = I am slightly positively energized

6 = I am moderately positively energized

7 = I am very positively energized

Input the data into the software to create an energy network map of the organization. Analyze the network by addressing the following questions:

• Who are the most positively energizing people in the organization?

• What is the density of the energy network, and how can it be enhanced?

• What are the key personal attributes of our most positively energizing people?

• What rewards or recognition should be given to those demonstrating high positive energy?

• What mentoring relationships should be created to take advantage of the positive energizers?

• What teams should be formed to capitalize on the positive energy network?

• What kinds of activities can be conducted to foster more positive energy in the organization?

• What are the leadership training and development implications for the organization?

• What implications for succession planning are implied by this energy network?

In providing feedback using this kind of map, be careful that you do not attach names to the nodes on the map—seeing that one’s position in the energy network is not as expected can cause emotional turmoil or embarrassment. Just use the map to give people a sense of how the organization is functioning, and then use the data to follow up with individuals who are in need of energy development and with individuals whose energy can be better utilized in the group or organization. Positively energizing teams can also be formed using those in the center of the network.

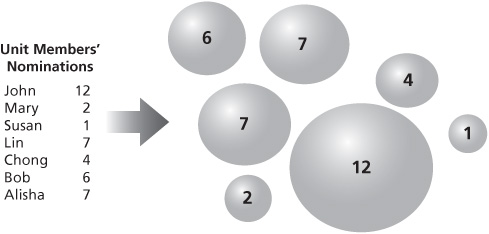

Bubble Chart

A second way to assess positive energy without using a statistical software package is to merely ask organization members to write down the names of the three people (or whatever number you think is appropriate) whom they would rate as the most positive, energizing people in the organization. Then tally the votes and create bubbles whose relative sizes represent the number of votes each person received. This will help you identify the positive energizers in your organization quickly.

The disadvantage of this technique, of course, is that you do not see the totality of the network ties, the density of the network, or the people who are de-energizers or “black holes.” It is just a simple and quick way to identify positive energizers in your organization. If Figure 10 represented the map of your own unit, for example, you would want to think carefully about recognizing and rewarding the energizing people, forming mentoring relationships between positive energizers and less energizing people, creating teams including energizers, leading developmental activities to increase the size of the bubbles, and so forth. Knowing who your positive energizers are gives you a distinct advantage.

FIGURE 10

A Positive Energy Bubble Chart

Activity

Bubble Chart

In your group or organizational unit, ask members to write down the names of three people whom they would rate as the most positive, energizing members. Tabulate the results by identifying the number of nominations received by each person. Create bubbles whose relative sizes represent the number of nominations each person received. There is no special way to arrange the bubbles on the page since their relative sizes provide the most important data.

Once you have developed the bubble chart, consider these questions:

• How many group members received no nominations or were left out? How might they be assisted?

• What is the relationship between hierarchical level in the unit and positive energy? (In some units, some junior-level people are giving energy to the system while some senior-level people are peripheral or are adding little positive energy.)

• Are you thoughtfully managing the energy network in order to capitalize on your positive energizers?

In providing feedback using a bubble chart, be careful that you do not attach names to the bubbles—seeing that one’s bubble is very small can cause emotional turmoil or embarrassment. Just use the chart to give people a sense of how the organization is functioning, and then use the data to follow up with individuals who are in need of energy development and with individuals whose energy can be better utilized in the group or organization.

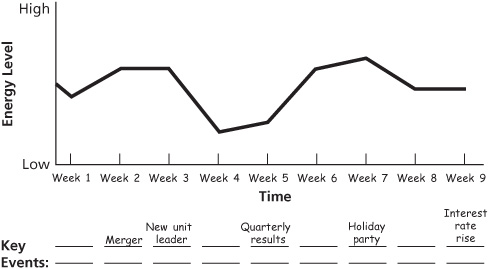

Pulse Survey

A third way to assess energy in your organization is to take a “pulse survey” on a weekly basis, asking employees, “On a 10-point scale, what is the level of your energy today?” Trend lines are tracked and averages are plotted over time for each unit or location. One CEO conducts this survey on a weekly basis and intervenes or provides needed support for units in which positive energy diminishes or in which trend lines turn down.

Use a graph like the one in Figure 11 to keep track of the energy levels of members in your unit over a period of time. Create an average trend line, and where there are significant changes in the trend, either up or down, note what events or incidents occurred around that time. This will help you discover factors that affect energy levels in your organization and identify people who are sources of positive energy as well as who are enablers and disablers of positive energy in the organization.

Now that you have been made aware of the importance of positive energy, you should identify your own key ideas for fostering and unleashing positive energy in your organization. Remember that positive relational energy is primarily a product of flourishing interpersonal relationships and is not the same as mere motivation, incentive systems, or recognition. Positive energy can be taught and learned, and effective positive leaders recognize, reward, and develop positive energizers.

FIGURE 11

Mapping Energy Via a Pulse Survey

CONCLUSION

Most people easily understand the concept of positive energy, but it is almost never consciously managed in organizations. One reason is that we really have not known how to define or assess it until recently. The scientific research is clear: positive energizers are significantly higher performers than their colleagues, and positive energy is, by a large margin, a more significant factor in the performance of individuals and organizations than people’s titles, the information they possess, the influence they exert, or their personality attributes. In my own work, I have found that positive energy is a dramatically underutilized resource and that identifying energy networks and highlighting the major sources of positive energy in an organization have been among the most important ways of improving performance.

In my own academic department at the University of Michigan, positive energy is so important that it is one of the key criteria we use for hiring new faculty members and admitting doctoral students. People have to be net positive energizers—adding more positive energy to the system than they extract—in order to be admitted as members. After twenty years of applying this criterion, it has produced a spectacularly high performing, energizing set of colleagues.

Again, positive energy is primarily a product of flourishing interpersonal relationships and is not the same as motivation, incentive systems, or recognition. Positive energy can be taught and learned, and effective positive leaders recognize, reward, and develop positive energizers.