5

HOW TO ESTABLISH AND

ACHIEVE EVEREST GOALS

Climbing Mt. Everest is among the most challenging activities most people can imagine. It requires supreme planning, training, effort, teamwork, and personal mastery. Very few of us have the physical, mental, and emotional capability to even attempt this level of performance. In organizations, Everest goals share similar attributes—they represent the peak, the culmination, the supreme achievement that we can imagine. They represent accomplishment well beyond ordinary success. But Everest goals are not just fantasies or dreams. They possess special attributes that actually motivate spectacular performance.

Everest goals have been found to help people accomplish outcomes that they never expected to accomplish, and they have helped organizations reach levels of performance previously unimagined.1 This chapter will help you begin the process of identifying an Everest goal for yourself and/or for your organization and assist you in developing a strategy for reaching the goal.

The first step in understanding the role of Everest goals is to understand the importance of goals and goal setting in individual and organizational performance. The chapter helps you identify the extent to which you recognize and utilize effective goals in your own life, and then the unique attributes of Everest goals are explained. Application activities will help you begin the process of establishing an Everest goal for yourself and/or for your organization.

THE IMPORTANCE OF GOALS

A great deal of research confirms that having goals motivates individuals and organizations to achieve higher performance than if they have no goals.2 For example, if you are assigned a task but are given no targets or standards for performance, you are unlikely to perform as well as if you are clear about the objective and the level of performance expected of you. Goal setting is a common strategy for helping individuals improve their performance. If we want high performance, we almost always establish goals as a way to attain it.3

In organizations, the situation is the same. Organizational performance is reliably predicted by the extent to which goals have been established. It is common in organizations, for example, for leaders to establish company goals for the year, goals for each subunit, annual goals for every employee, and long-term goals targeting several years into the future. Goals for motivating performance in organizations are almost universal.

TYPES OF GOALS

The kinds of goals established are important in predicting success. Figure 12 illustrates some of the effects of different types of goals on performance.4

Easy goals: If you are told that most people accomplish ten tasks per day but, because you are such a valuable employee, it is okay if you accomplish five tasks, you will most likely accomplish a number closer to five than to ten. Your performance will not be high with an easy goal.

General goals: If you are given a general goal such as “Do your best” or “Just work hard,” your performance will be higher than if you are given an easy goal. You will not likely slack off, but you will probably not achieve at the highest levels of your potential either.

FIGURE 12

Goal Setting and Performance

Stretch goals and SMART stretch goals: If you are told that you are such a valuable employee that you are sure to exceed the average of ten tasks a day and are given the goal of accomplishing fifteen tasks a day, it is likely that you will achieve a level of performance closer to fifteen tasks than to ten. Stretch goals are especially effective in influencing performance if they have five attributes characterized by the acronym SMART:

• S = Specific (versus general). A specific goal provides a clear standard or level of performance. Specific goals are precise, detailed, and explicit, and they are more likely to be achieved than general goals. For example: “Our goal is 95 percent customer satisfaction” rather than “Our goal is to have satisfied customers.”

• M = Measurable (versus vague). A measurable goal can be clearly assessed and quantified. Being able to measure goal achievement increases the likelihood that it will be achieved. For example: “Our goal is to win twenty games this season” rather than “Our goal is to have a successful season.”

• A = Aligned (versus unrelated). Aligned goals are consistent with the purposes of the organization. Aligned goals are more achievable because they engender support from others in the organization compared to goals that have little relationship to what the organization cares about. When it comes to individuals, such goals are aligned with core values, helping a person make progress on things he or she cares deeply about. For example: “Our goal is to donate ten hours per week for tutoring at-risk children” rather than “Our goal is to give time to community service.”

• R = Realistic (versus impossible to attain). A realistic goal should be difficult—that is, create stretch—but not impossible. Becoming an Olympic athlete by next month, for example, is not realistic for most people. Realistic goals are achievable rather than being merely fantasies or dreams. For example: “Our goal is to conduct at least one food drive every six months” rather than “Our goal is to wipe out poverty in Detroit.”

• T = Time-bound (versus limitless). A time-bound goal identifies a deadline for when the goal will have been achieved. Limitless goals can go on indefinitely with no real sense of whether the goal has been achieved or not. For example: “Our goal is to generate revenues of $15 million by the end of the fiscal year” rather than “Our goal is to reach a $15 million plateau.”

Activity

SMART Goals

Write down one goal that you have for your work, your personal life, or your family. Now, using the rating scale below, analyze your goal statement in terms of the extent to which it is a SMART stretch goal.

For a work-related goal, this activity is even more effective if you have a colleague who will rate your goal. Consider having everyone in your organization share and evaluate goals. That way, colleagues can provide suggestions for improvement to one another regarding the extent to which the goals are SMART stretch goals.

EVEREST GOALS

Everest goals represent a special kind of goals. While they usually have the attributes of SMART stretch goals, they also possess five unique attributes. They:

1. Are positively deviant

2. Represent goods of first intent

3. Possess an affirmative orientation

4. Represent a contribution

5. Create and foster sustainable positive energy

Everest Goals Represent

Positive Deviance

In English, the term deviance usually has a negative connotation. When we label someone a “deviant,” it is usually a criticism. Yet deviance merely refers to a condition that is not normal—an aberration from the standard or something that is unexpected.

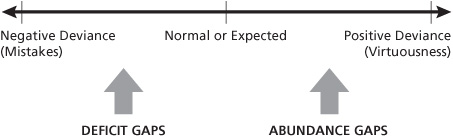

We can think, therefore, of negative deviance, but we can also think of positive deviance. To illustrate what positive deviance means, consider the continuum in Figure 13. A condition of negative deviance (represented by mistakes and errors) is represented on the left, a normal or expected condition is in the center, and a positively deviant or extraordinarily desirable condition is shown on the right. The right-hand point on the continuum can also be referred to as a virtuous state—meaning the best of the human condition or the highest aspirations that human beings hold for themselves.

An obvious example might be physical health. The large majority of medical research, and almost all of medical professionals’ time, is spent somewhere between the left point on the continuum (illness or injury) and the middle point (the normal condition of health), which is defined as an absence of illness or injury. Relatively little scientific attention is given to the gap between normal physical health (the middle point) and extraordinary vitality or, for example, Olympic-level fitness (the right-hand point). The right-hand end of the continuum represents a condition of positively deviant health. Scientifically, we know much less about positively deviant physical health than we do about illness.5

The space between the left-hand side of the continuum and the middle can be called the deficit gap, where there are problems, obstacles, and mistakes. The space between the middle point and the right-hand side can be called the abundance gap. Everest goals focus on the abundance gap rather than the deficit gap. They aim not just to overcome problems and achieve success but to reach extraordinarily high levels of performance—performance that spectacularly and dramatically exceeds normal.6 In this they are similar to an abundance culture in organizations by reaching for the highest aspirations of humankind.

Everest Goals Represent Goods

of First Intent

Everest goals are also virtuous, focusing on achieving the best of the human condition, in that they are similar to what the Greek philosopher Aristotle called “goods of first intent.” Goods of first intent, he proposed, represent that which “is good in itself and is to be chosen for its own sake,” such as love, wisdom, and fulfillment.7 Goods of first intent possess inherent value and are desirable because of intrinsic value. On the other hand, goods of second intent include “that which is good for the sake of obtaining something else,” such as profit, prestige, or power.8 One indicator of the difference between goods of first intent and goods of second intent is that people never tire of or become satiated with goods of first intent. It is not possible to get too much of a good of first intent, such as love or wisdom. This is not true of goods of second intent which can lead to satiation and diminishing returns.

Like Aristotle’s goods of first intent, Everest goals possess inherent meaning and purpose. With an Everest goal, achieving the outcome itself is sufficient; the goal is not a means to obtain another end, such as recognition, reward, or acclaim. The achievement of the Everest goal itself possesses all the value and significance that we need.9 This is very much akin to feeling a sense of calling in work.10

Everest Goals Possess an

Affirmative Orientation

An affirmative orientation refers to an inclination toward positive possibilities—toward “Why not?” rather than “Why?” Everest goals do not merely focus on solving problems, reducing obstacles, overcoming challenges, or removing difficulties. Rather, Everest goals focus on opportunities, possibilities, and potential. Everest goals are more likely to emphasize strengths and capitalize on gifts than address weaknesses and past failures. They affirm an optimistic orientation. They do not merely eliminate problems. With an Everest goal, virtuousness is the desired outcome.11

Everest Goals Represent a Contribution

The achievement of a goal can be thought to provide benefits or rewards either to the person pursuing the goal or to others. Thus, goals can be categorized as achievement goals (when they benefit the person pursuing the goal) or as contribution goals (when they benefit others). Most people pursue both kinds of goals, but one or the other type usually predominates in people and in organizations.

Achievement goals emphasize self-interest, achieving desired outcomes, obtaining a preferred reward, accomplishing something that brings self-satisfaction or enhances self-esteem, and creates a positive image in the eyes of others. Individuals who emphasize achievement goals are primarily interested in proving themselves, reinforcing self-worth, or demonstrating competency. Attaining desired performance outcomes is the primary objective.

Contribution goals focus on providing benefit to others. These goals emphasize what individuals can give compared to what they can get. Contribution goals are motivated more by benevolence than by a desire for acquisition.

Jennifer Crocker and her colleagues found that goals focused on contributing to others produced a growth orientation in individuals over time, whereas self-interest goals produced a proving orientation over time. In studies of individuals tracked over several months, Crocker found that contribution goals led to significantly more learning and development, higher levels of interpersonal trust, relationships that were more supportive, higher performance, and less depression and loneliness than did self-interest goals. Most important, when contribution goals predominated, the meaningfulness of activities was substantially higher than when self-interested goals predominated.12

Everest goals focus on contributions rather than personal benefits, the creation of value rather than personal payback, and ensuring value for others rather than acquisition for oneself. Contribution goals enable the best of the human condition.

Everest Goals Foster Sustainable

Positive Energy

As Chapter 3 mentions, there are several kinds of human energy: physical, emotional, and relational. Of the three types, only relational energy is renewed with use rather than exhausted, and this is why it is associated with positive, supportive relationships. Positively energizing relationships are amplifying in that they create additional energy the more they are used. Loving, caring relationships are renewed the more we engage in them. Moreover, this form of energy is its own reward. People do not pursue relational energy in order to obtain another, more important outcome. It is sufficient in itself.

Similarly, Everest goals are inherently energizing. We are not exhausted by pursuing Everest goals; instead we are uplifted, elevated, and energized. Nor do we need another source of motivation to pursue them: the goal itself provides the necessary positive energy for its pursuit. Ed Deci’s concept of intrinsic motivation shares a similar connotation.13

Everest goals are not the same as personal mission statements, life purpose statements, or statements of what we stand for. Everest goals are also not the same as an organization’s core competencies, a corporate vision statement, or a strategic plan. Such philosophical statements differ from Everest goals because they do not have the five SMART attributes. Everest goals are, first and foremost, goals—they drive behavior.14

AN EXAMPLE OF AN ORGANIZATIONAL EVEREST GOAL

Everest goals are difficult to develop—they usually cannot be developed off the top of the head or after superficial consideration. In fact, most individuals and organizations have never developed these kinds of goals for themselves. Although there is no boilerplate way to determine appropriate Everest goals, it may help to have some examples of Everest goals established by organizations that produced dramatic improvement.

For example, in 1951 the U.S. government established a facility in Colorado to produce the triggers used in the nuclear weapons stockpiled during the Cold War. At the end of the Cold War, the U.S. Department of Energy mandated that the site—labeled by ABC News as the most dangerous place in America due to the amount of radioactive and explosive materials stored on the site, including plutonium, enriched uranium, and dangerous chemicals—be closed and cleaned up. A blue-ribbon panel of experts from around the globe conducted a study to determine how long the cleanup would take and how much it would cost. The most optimistic estimate was seventy years at a cost of $36 billion, although the more realistic estimate was two hundred years and several hundred billion dollars.

The company that won the contract established the following Everest goal—thought at the time by the Department of Energy, the Government Accountability Office, and the other nuclear facilities throughout the country to be delusional: “We will clean up and close the facility in twelve years in order to remove as quickly as possible, and forever, the threat of personal harm, pollution, and the dangers of radioactivity for our children and grandchildren.” The consequence of establishing that goal was that the cleanup and closure actually took only ten years at a cost of $6 billion, and it left the site thirteen times cleaner than required by federal standards.15 Let us highlight this goal’s Everest attributes.

• The original goal of twelve years was positively deviant, as experts considered that time frame to be fantasy.

• The driving motive of the goal, to make the world safe for future generations, was a good of first intent. No more important outcome was needed.

• The goal focused on positive possibilities—to exceed all realistic estimations—despite pervasive opposition from others. Thus, it had an affirmative orientation.

• Workers were making a contribution to others and to future generations. Furthermore, they were willing to sacrifice, for others’ benefit, the extra money they could have earned by stretching out the job.

• The challenge created sustainable positive energy, engendering passion and complete dedication in employees, even to the extent of enthusiastically giving up their jobs.

Another example is the Everest goal established in 2005 by the leadership team at one of the Prudential Financial Services companies. The pressure on this firm from Wall Street to achieve financial success was tremendous. The initial goal, therefore, was stated in financial terms: “We want to earn $10 million in profits by 2010”—at the time an almost impossible goal.

However, after learning about the concept of Everest goals, the leadership team decided to change the wording of the goal. Leaders recognized that few employees get up each morning energized by and passionate about earning $10 million in profits. The goal was altered, therefore, to better reflect the attributes of Everest goals: “We will ensure that ten million people will have secure retirement by the year 2010.” Given performance trends current at the time, this goal represented a positively deviant target in everyone’s minds. Now employees could imagine their grandparents being assured of a reasonable quality of life in retirement: a good of first intent. They could imagine an elderly friend whose medical care was ensured because of the company’s commitment, giving the goal an affirmative orientation. They could envision making a contribution to people they would never meet but whose lives would be better because of their success. And the sustainable positive energy that was generated by this goal led to extraordinarily high performance levels. The trajectory of the firm’s performance changed markedly after its goal became Everest-like.

Other examples of company Everest goals include the following:

• Ford Motor Company: democratize the automobile (early 1900s)

• Boeing: bring the world into the jet age (1950s)

• Sony: change the image of poor quality in Japanese products (1960s)

• Apple: one person, one computer (1980s)

An example of an Everest goal in business that is outside the framework of a single company is the C. K. Prahalad Initiative, which seeks to reframe the way businesses deal with the world’s poorest inhabitants. It asserts that companies can “tap new markets while solving some social problems and empowering the estimated four billion people living on less than $2 a day.”16 Here the goal is to have half a million Indians become employable within ten years.

Everest goals are not the same as mere stretch goals, in that they extend beyond them. Sometimes SMART stretch goals share some of the attributes of Everest goals (most particularly the emphasis on positive deviance), but usually they are lacking some or all of the other four (good of first intent, affirmative orientation, contribution, and sustainable positive energy). You can see the differences when you look at some of the following company stretch goals from the past fifty years that are not Everest goals: GE’s “Be #1 or #2 in every market we serve,” Walmart’s “Become the first trillion-dollar company,” Philip Morris’s “Knock off RJR as the #1 tobacco company,” Nike’s “Crush Adidas,” Honda’s “Destroy Yamaha,” and Giro Sport’s “Become the Nike of the cycling industry” (which, incidentally, built on Nike’s success at its own stretch goal from several decades earlier).

AN EXAMPLE OF AN EVEREST GOAL FOR INDIVIDUALS

Individuals may also identify and pursue personal Everest goals on their own. These have the same attributes discussed above: the same standard of positive deviance, the same inherent meaningfulness, the same affirmative orientation, the same focus on contribution, the same positive energy. Identifying an Everest goal can allow a person to do something he or she would normally consider to be impossible.

One example is Rick Hoyt, then a wheelchair-bound student at South Middle School in Westfield, Massachusetts, due to cerebral palsy. Rick came home from watching a high school basketball game one day and told his father—with the help of a head switch atop his wheelchair—about a charity road race staged to benefit a fellow student who was paralyzed in an auto accident. Rick told his father he wanted to be a part of the race. Dick Hoyt decided to establish an Everest goal. Never mind that he was 40 years old and ran just once a week. Never mind that he only ran a mile at a time, at most. Never mind that he was not only being asked to run five miles but to push his son and a 50 pound wheelchair with him. His son wanted to be a part of this race. That is how the Everest goal got set. Since then, Rick and Dick Hoyt have completed 50 marathons and 121 triathlons. They also crossed the country on a bicycle, completing the 3,700 mile trek in 45 days. Importantly, a key objective of the Everest goal was to break down barriers regarding people with disabilities and to teach people about Everest goals. Everest goal achieved.

Activity

Personal Everest Goal

The questions below are intended to help you clarify and pinpoint an Everest goal for your own life. This is not a personal mission statement or a philosophy of life. Because it is an Everest goal, it has SMART attributes—something that can motivate behavior.

Such a goal may relate to your role at work, your life outside of work, your relationships, or something very personal within you. Do not be frustrated or disappointed if nothing comes immediately to mind. Many people have never identified such a goal for themselves, and it is not a quick and easy task to identify an Everest goal that is real and that is meaningful to you. Sometimes this task takes a great deal of contemplation, feedback, and self-analysis, but the outcomes are worth the effort.

• What represents positively deviant performance—significantly above the norm—for you?

• What do you consider an inherently valuable accomplishment, even if no other benefit accrues to you?

• Are you focusing on an affirmative orientation—on positive possibilities—rather than on solving a problem, on abundance rather than overcoming a deficit?

• What contribution will you make to others by achieving this goal?

• Does the goal provide you with energy, enthusiasm, and excitement even if you have no other incentives besides the goal itself?

• In an area about which you care deeply, what is the best performance you can imagine?

• For what do you have passionate commitment and a willingness to put forth full effort to achieve it?

• Do you have a support system that can assist you with your goal accomplishment?

Activity

Organizational Everest Goal

Everest goals are intended to push individuals and organizations to their ultimate limits. Achieving Everest goals in organizations creates spectacularly positive outcomes, but no organization becomes extraordinary by chance. Either a conscious decision is made to pursue an Everest goal or positively deviant performance is unlikely.

Of course, establishing organizational Everest goals is best performed in collaboration with members of your organization. Any attempt to simply superimpose an Everest goal on an organization is doomed to failure. This is because the attributes of Everest goals must be clarified, approved, and shared among those who will be accountable for the organization’s performance.

Coming up with an organizational Everest goal will take multiple meetings and intensive discussions among the relevant constituencies. Considering the following questions, however, will give you a head start on that process.

• What achievement represents the culmination—the very best—our organization can be?

• What would create passion among employees?

• What does our organization care deeply about?

• What represents our organization’s ultimate destiny?

• What legacy would we like our organization to leave?

• What human benefits do we want to produce?

• What core values and virtues do we represent?

• How can we have an impact that extends beyond immediate outcomes?

• What ripple effects can we create?

• What do our customers or clients care deeply about?

• What outcome is more important than the organization’s success?

• What is the best possible outcome we can imagine?

ACHIEVING EVEREST GOALS

Merely establishing an Everest goal is no guarantee that performance will change in any way, of course. Goal statements must be accompanied by additional assistance. Specifically, the goal must be integrated with a set of action steps and accountability mechanisms.

Some years ago, before gastric bypass surgery was invented, a young woman became so depressed that she made the decision to commit suicide. She wanted nothing more than to be married and have children, but she weighed more than four hundred pounds, and she felt that, given her size, it was highly unlikely that she would find a marriage partner and be healthy enough to have children. She had tried stretch goals, SMART goals, incentive systems, therapy, and a host of fad diets to try to change her size, but nothing worked. Finally, in a tremendous amount of emotional and psychological pain, she decided to give up.

Before she was able to put her suicide plan into action, however, she became aware of the concept of Everest goals. With the assistance of a coach and counselor, she decided to see if this tool could help her. The Everest goal she established was to lose a hundred pounds in the next twelve months. Now, this might ordinarily be labeled as merely a SMART stretch goal, but she had been living with those kinds of goals for many years without any progress. For her, only when the goal of losing weight was consciously attached to the five attributes of Everest goals did it change in its character. Such a large weight loss in such a short time was obviously a positively deviant goal, but she also found ways to associate the goal with a good of first intent, an affirmative orientation rather than merely a problem-solving approach, a contribution rather than the pursuit of purely personal benefits, and a source of sustainable positive energy rather than a tortuous journey. The goal took on a much broader meaning than simply to become physically smaller.

She checked with a physician to ensure that this would not be dangerous to her health, and she garnered the assistance of a large social support network to assist her. It was not enough for this network of supporters to merely cheer her on, give her moral support, and be there for her. She already had moral support and friendships, and those had not been enough for her to accomplish an Everest goal.

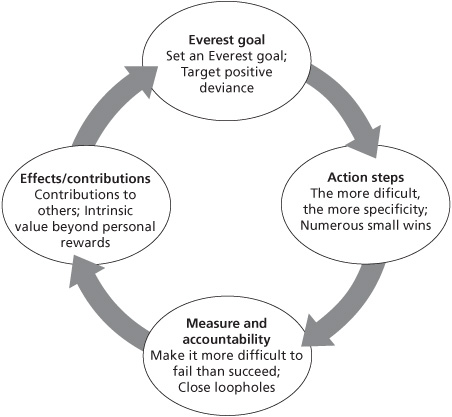

Instead, she put the following process into place as summarized in Figure 14:

1. Set an Everest goal

2. Identify multiple specific actions

3. Make it more difficult to fail than to succeed

4. Determine effects

The first step, of course, is to establish an Everest goal. But to achieve that goal, three more steps are crucial. The second step involves identifying multiple, specific action steps. The principle is that the more difficult the goal, the more numerous and more specific the action steps must be. For example, this young woman determined that she would not shop for food alone, and she would not shop without a menu. She would meet a friend each morning before work to go to an exercise class. She would carry only enough money in her purse for bus fare, not enough for a hamburger or a bag of donuts. Someone would eat lunch with her each day to ensure that she kept to her targets for portion control. She would only watch television while walking on a treadmill. And, she regularly attended support group meetings. These were just a few of her action steps—the list came to more than twenty. This meant that by the end of each day, she had achieved numerous small victories. These small wins, rather than failures and embarrassments, began to dominate her life. The victories contributed to sustainable positive energy.

FIGURE 14

Achieving Everest Goals

The third step, making it more difficult to fail than to succeed, is important because when most of us face a challenge to reach positive deviance, we frequently figure out loopholes that allow us to avoid having to really accomplish the goal. This step closes those loopholes. The young woman in the example took measures that made it more difficult to stay the same weight than to lose weight. Activities included a contract with her supervisor at work to cut her salary in 10 percent increments if she did not achieve weight loss benchmarks; scheduling public weigh-ins at work; an agreement that if she did not lose the weight by the end of the year, her physician would hospitalize her and put her on an intravenous diet until she lost the weight—at a cost to her of $400 per day; and many other activities. She had at least a dozen similar accountability mechanisms, all designed to make it more expensive, more embarrassing, and more difficult to fail than to succeed. This meant that she had both positive incentives and the threat of negative incentives associated with the pursuit of her goal.

The fourth step emphasizes the contribution and the intrinsic motivation associated with the Everest goal. As explained earlier, contribution goals produce more success than achievement goals, and the inherent meaningfulness of the activity produces the positive energy necessary to follow through. For the young woman in the example, staying alive trumped all other outcomes, but that is not all. She turned her attention to contributing to the welfare of others, investing in inherently meaningful activities, and focusing on the long-term, multigenerational effects of her actions.

Did she succeed? Not only did she lose a hundred pounds in twelve months, she went on to eventually lose more than 50 percent of her starting weight.

Activity

Action Steps and Accountability

For either your personal Everest goal or your organizational Everest goal, write down several specific action steps (with corresponding small wins) and the accountability mechanisms (measures, metrics, milestones) you can put into place to help ensure progress toward your Everest goal.

CONCLUSION

Goal setting is a common technique for motivating performance and for maintaining accountability, but as this chapter has highlighted, there are differences between normal goals and Everest goals. Everest goals possess the same attributes as SMART goals—they are specific, measurable, aligned, realistic, and time-bound—but Everest goals possess five additional attributes that make them unique. Everest goals are associated with positive deviance—extraordinarily positive performance. They are associated with Aristotle’s goods of first intent, which have inherent value and a sense of calling associated with their pursuit. Everest goals possess an affirmative orientation rather than a problem-solving orientation—the pursuit of the good trumps the mere elimination of a problem. They aim to provide a contribution regardless of personal benefit. And, Everest goals create and foster sustainable positive energy. They require a support system and a process for maintaining focus, but the pursuit of the goal itself is energizing.