5

Types and Examples of Unethical Conduct and Corruption

The educated citizen has an obligation to uphold the law. This is the obligation of every citizen in a free and peaceful society, but the educated citizen has a special responsibility by the virtue of their greater understanding. For whether they have ever studied history or current evets, ethics or civics, the rules of a profession or the tools of the trade, they know that only a respect for the law makes it possible for free people to dwell together in peace and progress.

John F. Kennedy

5.1 Introduction

The above statement from the former President of the United States of America typifies the degree to which upholding the law and not breaching legal or ethical standards is so important for the societies we live and work.

This chapter of the book will identify the various types of unethical and illegal practices from misuse of power to serious fraud. It will articulate what constitutes each type of unethical and illegal practice and how they can occur in a business context. It will provide a list as part of a toolkit and practical guide for what to do and what not to do for ethical compliance. Furthermore, it will explain how construction professionals can decipher what represents unethical conduct and practices in an attempt to regulate their behaviours and actions and those of others. In this regard, as a practical guide it will offer both hypothetical and real-life examples of situations and scenarios where breaches of ethical standards and illegal activity has ensued. Furthermore, it will identify and discuss the damage that can be caused, both at an individual and organisational level, in such cases as a deterrent to bad practices.

The chapter will discuss how the type of unethical or illegal behaviours could vary between different roles and responsibilities within the construction industry from clients down to subcontractors and suppliers in the order of hierarchy. Finally, the measures that can be adopted to reduce unethical and illegal practices across the world will be highlighted with reference to some initiatives that have been spearheaded in the developing world.

5.2 How Should Construction Professionals Recognise Unethical Conduct and Practices?

There is a major issue and potential problem relating to the question of what constitutes unethical behaviour in practice. As previously highlighted in Chapter 3 there is no universal theory of ethics with different cultures existing within the construction industry and this creates problems and dilemmas in what is ethical or non-ethical (Liu et al. 2004). Clearly this reinforces the need for construction professionals to have a consistent approach to ethics which can be applied across the whole industry. Liu et al. (2004) explained, however, that this notion of achieving consistency is linked to the different cultures which exist within the construction industry and this may make boundaries between ethical and non-ethical behaviour become blurred at times. A practical example of this could include the boundary between receiving a seasonal gift as a polite gesture and what is deemed to constitute an act of bribery to influence an award of a contract for instance and this was covered in the last chapter. Vee and Skitmore (2003) attempted to address this potential grey area and offered clarity on the boundary between gifts and bribery. They concluded that gift-giving transfers become an illegal act of bribery when they compromise relationships between the gift giver and receiver and favour the interests of the gift giver. This is an important aspect for construction clients, especially at tender stages when bidders may offer them gifts or invitations to corporate functions, to gain competitive advantage over their competitors. It is normal for construction professionals to have to sign up to anti-bribery legislation and declare gifts to avoid accusations of impropriety in such cases. Other forms of unethical behaviour could include breach of confidence, conflict of interest, fraudulent practices, deceit and trickery. What constitutes unethical behaviour in practice is not always black and white and can come in many shades of grey owing to interpretation difficulties. For instance, less obvious forms of unethical behaviour could include presenting unrealistic promises, exaggerating expertise, concealing design and construction errors or overcharging (Vee and Skitmore 2003).

5.3 Examples of Acts of Unethical Behaviour and Corruption

It has been argued that the construction industry provides a ‘perfect environment for ethical dilemmas, with its low-price mentality, fierce competition and paper-thin margins’. Transparency International which represents a global coalition against corruption found that 10% on the total global construction expenditure was lost to some form of corruption in 2004, which is staggering and further depletes the reputation of the industry. There have been growing reports over the years that unethical behaviours and practices are still in some areas of the construction industry are still common, and this is taking a toll on public confidence and trust. FMI Capital Advisors (2004) undertook a survey which concluded that 63% of construction professionals felt that unethical conduct was still a problem for the industry. This clearly demonstrates that some improvement measures are required.

According to Parson (2005) unethical behaviours have received negative press coverage and have had a detrimental reputational effect on those organisations involved. Financial irregularities, scandals, blacklisting and what could the press have referred to as ‘dirty tricks’ have brought the UK construction industry into disrepute in recent years. Many cases of financial impropriety, false reporting and fraud have entered into the courtroom sometimes resulting in fines, and in extreme cases imprisonment.

In the construction industry, ethical behaviour is measured by the extent by which integrity and trustworthiness is inherent within business conducted by individuals and organisations (Parson 2005). It is particularly complicated in the sector when one considers the different and sometimes conflicting relationships between the project owners (clients), design consultants, main contractors, subcontractor and suppliers. From ‘The Survey of Construction Industry Ethical Practices’ conducted by FMI Capital Advisors on a large variety of construction stakeholders, the most frequent and reported issues of unethical behaviours related to such activities as overcharging, unfair claims for additional works and bid shopping. The extent of each of these reported practices varied between stakeholder groups. For instance, clients reported their main concern as being overzealous’ claims conscious’ main contractors whereas subcontractors reported their main issue as late payment, even when main contractors have been paid on time. Main contractors reported that bid-shopping, the practice of clients divulging solicited bids as leverage to encourage them to reduce their lower their prices, was the most concerning for them. According to Parson (2005), this illustrates that the nature and importance of unethical practices changes between the different stakeholders. The other complication revealed by the survey is that the degree to which respondents felt one practice to be unethical is dependent on the type of stakeholder. For instance, the majority of clients felt that the practice of bid-shopping was not unethical but good business practice, and the same was true when main contactors responded to them being ‘claims conscious’ on projects. Accordingly, this demonstrates that the level of acceptability for certain practices lie in the eyes of the beholder, which will vary between the different parties to the construction process. Subcontractors, who are conscious that they are relatively low down on the food chain sometimes feel that they are the ones who bear the brunt of financial burdens to cut costs on projects, which is commonly referred to as ‘value engineering’.

A lot of gamesmanship on construction contracts occurs because the different players have varying degrees of understanding of what constitutes the regulations and rules, especially where tendering and procurement practices are concerned. Accordingly, one party may consider one practice to be acceptable and ethical, whereas another may find it totally unacceptable and unethical. This presents an ethical dilemma for the industry especially as there are no universal standards which offer clarity in this regard. For instance, in some countries reverse bidding, which could be compared with auction sites in reverse, is viewed as acceptable practice, especially amongst construction clients. These individuals might consider that such bidding makes good business sense in securing the best price for the work, but others who feel this is an immoral way to procure tendering processes. Some have argued that reverse bidding could be regarded as ethical as long as the rules were clearly set down to all bidding contractors; however, some would challenge this on the grounds of fairness and transparency.

Another example of questionable behaviour is over-bidding whereupon main contractors and subcontractor charge their clients more than the value of the works they have undertaken, especially at early stages of contracts. This is sometimes facilitated by them ‘front-end loading’ their financial valuations to reflect being paid more at the start than the end of construction periods. Some contractors would argue that this is a necessary and acceptable practice to maintain their cash flow, especially where clients pay them late and deduct monies as retentions in some cases. This may have some legitimacy as most cases of insolvency, especially those smaller construction companies, have been attributed to late payments by their clients.

From a survey carried out by Vee and Skitmore (2003) on construction professionals in Australia, all those interviewed had witnessed or been privy to some degree of unethical behaviours in the past. Such behaviours and practices from the survey are reported in Table 5.1 with percentages relating to how frequent respondents had witness that particular category of unethical conduct.

| Category of Unethical Conduct | Survey Percentage |

|---|---|

| Negligence | 67% |

| Unfair conduct | 81% |

| Fraud | 35% |

| Violation of environmental ethics | 20% |

| Bribery | 26% |

| Conflict of interest | 48% |

| Collusive tendering | 44% |

| Confidentiality and propriety breach | 32% |

Clearly the above data is quite alarming when considering the frequency percentages that respondents had witnessed the various forms of unethical conduct in the construction industry.

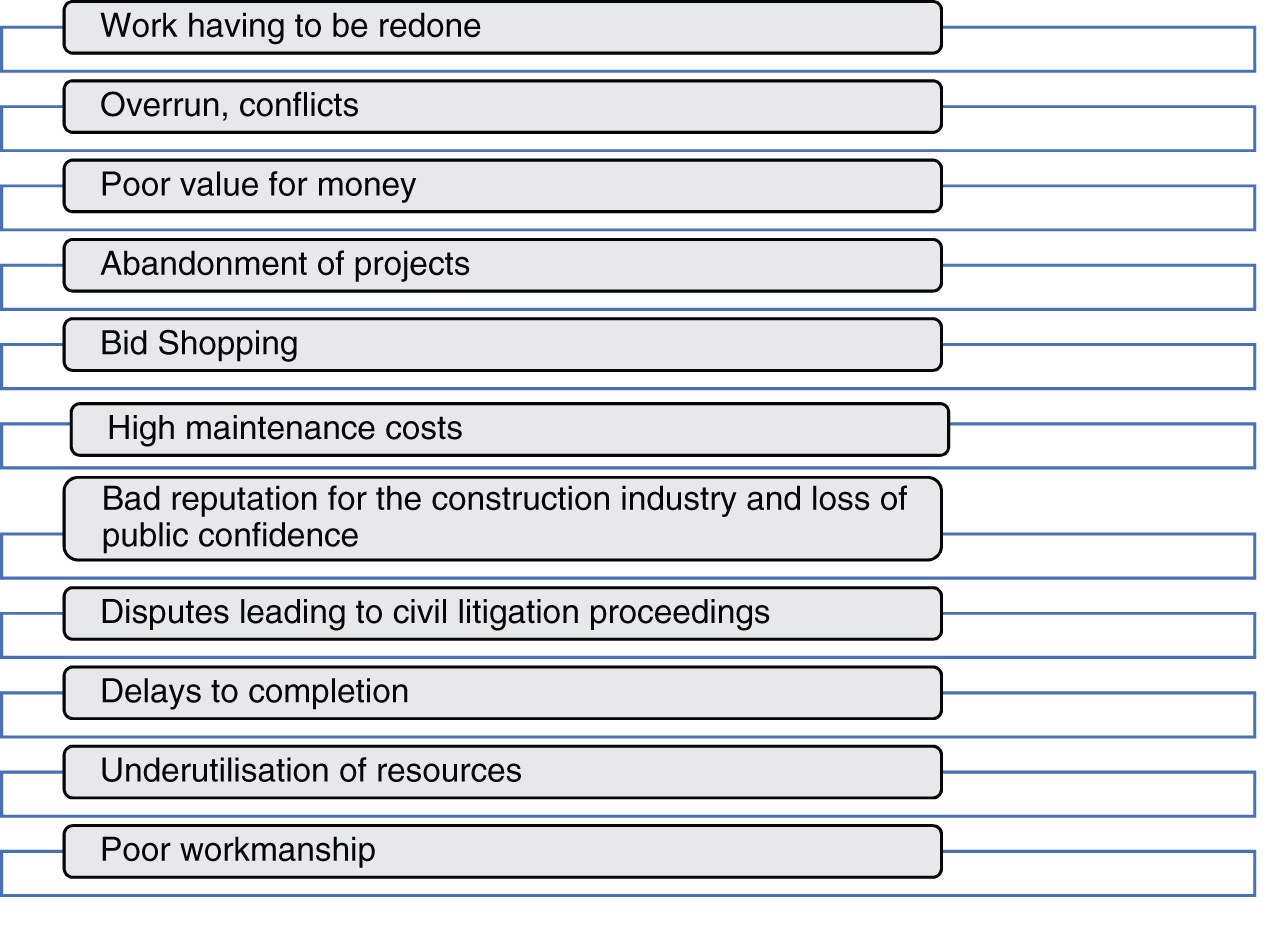

One attempt to address unethical behaviour in this way comes from The Global Infrastructure Act Anti-Corruption Centre, which published a guide with examples of corruption in the infrastructure sector to assist practitioners. It identified the different criminal acts of fraud including collusion, deception, bribery, cartels, extortion, offences at pre-qualification and tender and dispute resolution (Stansbury 2008). In addition, a survey was conducted by Abdul-Rahman et al. (2007) which looked at ethical problems on building projects in Malaysia and some of the examples of unethical and illegal practices are illustrated in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Examples of unethical and illegal practices on building projects in Malaysia. Based on Abdul-Rahman et al., 2007.

5.4 Misuse of Power

Other less obvious examples of unethical behaviour could emanate from the misuse of power within organisations. This could relate to a manager making unfair or unreasonable demands on one of their subordinates or displaying intimidating behaviour or undermining their staff. In some organisations power can come from an ‘illegitimate’ form (Walker 2009). This type of power exists outside the formal (or legitimate) authority structure such that the individual exercising power imposes their will on others in the organisation. An example could be an individual who has influence on a senior manager sometimes coined as having ‘the ear of the boss’. In such cases, this individual could strongly influence the senior manager’s own opinions or actions against another member of staff which can be extremely damaging. This can sometimes occur where there is a relationship or marriage between the individual exerting illegitimate power and the senior manager. Such power can be utilised from an unethical standpoint to further the objectives of the individual rather than those of the organisation. For this reason and coupled with fact that the power is gained outside of the formal line management structure, it can exert a feeling of disquiet in a business context. According to Walker (2009) another category of power that could be regarded as unethical could be ‘Coercive’ power and is associated with bullying and controlling.

Considering the above, it is perhaps not surprising that the reputation of the construction industry has been tarnished over many years, which has culminated in a general lack of trust and confidence (Challender 2019). This has been a worrying trend and measures are required to address this problem. In instances where ethics have not been maintained this frequently leads to disputes between construction professionals. Some have argued that new players in the construction industry could be emerging with a general lack of appreciation of construction ethics with greed as their main driver. Their conduct in this way can not only affect project outcomes but their ability to manage such aspects as health and safety at work and prevent accidents on site. This is especially relevant for the construction industry given that those people employed in construction contracting are twice as likely to be killed in accidents when compared with the average for all other industries. Accordingly, many individuals have lobbied for the industry to undertake reforms to root out those organisations and people who have breached ethical standards and remove them from the market.

5.5 Corruption

Corruption can be defined as a form of dishonesty or criminal offence undertaken by a person or organisation entrusted with a position of authority, to acquire illicit benefit or abuse power for their own private gain (Fewings 2009). Strategies to counter corruption are often summarised under the umbrella term ‘anti-corruption’. Corruption can be grouped into two main areas. The first, ‘administrative corruption’, is the corruption and bribing of officials, to be treated more favourably. Such officials could include clients for awarding of contracts or local authority representative for receipt of planning permissions or licenses. Moreover, state corruption is associated with individuals trying to change laws or avert the course of justice and can also apply to political figures who act in a biased way to support a particular party who is bribing or lobbying them. Although corruption in not endemic in the UK, there are significant problems which need to be addressed to understand where, why and how it is happening in order to address it. Reasons for corruption are varied but especially in undeveloped economies could be related to underprivileged and underpaid government officials who see acts of bribery as a means to bolster their incomes. However, corruption can ensue in all economies, rich or poor, for reasons of greed and desires linked to furthering their own private interests.

Corruption can be divided into four main categories and these are extortion, bribery, concealment and fraud. Extortion is where a payment is demanded through means of blackmail and where those affected are forced to comply with demands or face the consequences. An example could involve someone gaining personal information on another and uses this information to threaten to disclose this unless a cash payment is given. Bribery is associated with giving or receiving a reward in order to facilitate favours from an individual or organisation. Bribery normally transcends into fraud through false accounting or falsifying documentation for a particular purpose. Tax evasion and wrongfully approving sub-standard work for personal financial gain is treated in the courts as fraudulent activity. Concealment can be associated with corruption and normally involves an agent who facilitates bribe payments. This practice sometimes involves subsidiary companies and transferring and concealing money in offshore accounts for tax evasion purposes. Corruption can take the form of corrupt power where normal competition rules are breached and distorted by a few influential and privileged companies. These can take the form of cartels and serve to increase prices to the detriment of their clients and competitors. These practices can commonly be associated with procurement of building projects at tendering stages and thereby requires robust governance, close scrutiny, reporting and audit to counter such opportunities.

The principle of fair transaction and competition is placed at the heart of ethics and ethical behaviours in a concerted attempt to eliminate corruption. Organisations seek to become transparent in their business dealings to avoid the risk of accusations of unfair or illegal dealings, and therein improve their trading reputation. In some cases, the degree of transparency has to be balanced against the need to maintain client confidentiality which is also a professional responsibility. For regulation of activities there are many areas of business where close scrutiny is called for. These include audit, financial reporting, procurement and remuneration. The concept of transparency is a critical tool in avoiding corruption practices but relies on the principle of eliminating unfair advantage.

Transparency International is a global civil society organisation leading the fight against corruption, and it promotes anti-corruption measures by working in close collaboration with construction participants worldwide. It concurs that it is imperative that all participants in construction projects co-operate in the development and implementation of effective anti-corruption actions in order to eliminate corruption and to address both the supply and demand sides of corruption . The Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre, (GIACC 2008) has provided 47 examples of construction related activities that are construed as being corrupt and related to the criminal offences of collusion, extortion, fraud, deception, bribery, cartels or similar offences. These are included in Figure 5.2 and are categories into the three categories, namely Pre-qualification and Tendering, Project Execution and Dispute Resolution.

Figure 5.2 Examples of corrupt construction-related activities (adapted from GIACC 2008).

Some hypothetical examples in each of these three categories applied to the construction industry are provided below.

Whilst the above cases are hypothetical, there have been many reported real-life examples of fraudulent activity in the construction sector. Where this has occurred, it has been very damaging for the reputation of those organisations, with them being found guilty of breaching ethical standards and committed criminal offences. The case of construction and professional services company Sweett Group PLC in February 2016 was one such example on a global scale, where they were sentenced and ordered to pay £2.25m after a bribery conviction. The case involved their failure to prevent an act of bribery in the United Arab Emirates to secure the award of a contract for the building of a hotel in Abu Dhabi. The Serious Fraud Office (SFO) uncovered that a subsidiary company, Cyril Sweet International Limited, had made corrupt payments to a Real Estate and Investment arm of Al Ain Ahlia Insurance Company (AAAI). The Director of the Serious Fraud Office David Green QC articulated after the case that:

Acts of bribery by UK companies significantly damage the country’s commercial reputation. This conviction and punishment, the SFO’s first under Section 7 of the Bribery Act, sends a strong message that UK companies must take full responsibility for the actions of their employees and in the commercial activities act in accordance with the law.

This caused worldwide negative for the organisations involved and the construction industry at large. Sweet Group PLC were ordered to write to all their existing clients to provide a full and comprehensive account of the conviction which led to extremely bad press for them. The full details of this case will be covered later in this chapter. This potentially could have caused them to become insolvent, due to reputation damage and significant decrease in work as a consequence.

5.6 Fraud

According to Fewings (2009) fraud can pose one of the biggest risks to organisations. Fraud can take many different forms but most prevalent in the UK is cybercrime. In the past, there have been instances where emails have been received that have stolen the identities of organisations. Where clients have large construction projects on site, it can be sometimes a magnet for acts of fraud to be enacted. This could start with a perpetrator calling the client and pertaining to be the contractor, advising that their bank details have changed and requesting that the client make the necessary changes on their finance system. Procedures should be in place not to comply with bank change requests of this nature but nevertheless a financial controller should not make the changes without adherence to special controls and procedures. Coupled with the change of bank details, frauds of this nature involve the raising of a bogus invoice claiming to be from the contractor, after which bank transfers are made to them and the monies fraudulently channeled through to the criminal organisation. In such circumstances money transfers normally are wired oversees and the Serious Fraud Squad in the UK find it extremely difficult to identify the perpetrators who have taken on a false identity. Retrieval of any funds transferred can be even harder and insurers do not normally cover organisations for such loses. This can leave a company in a poor financial position as a consequence of the financial loss. In a construction context consider the hypothetical example below:

5.7 Bribery

One of the most common forms of unethical conduct is bribery which is described as:

Offering some goods or services for money to an appropriate person for the purpose of securing a privileged and favourable a privileged and favourable consideration of one’s product or corporate project.

Vee and Skitmore (2003)

Bribery relates to a conscious effort to influence another person or organisation with a gift or payment that generates an unfair advantage. It normally involves moving from a position of providing an acceptable payment for goods or services to an attempt to distort an outcome to generate an advantage (Fewings 2009). According to Usman et al. (2012) there are two types of bribery; ‘Active’ and ‘Passive’. Active bribery relates to the promise or offer of any financial or other advantage, directly or indirectly with the intention to induce or reward a person for the improper performance of a function. Passive bribery relates to the request, acceptance or agreement to receive any financial or other advantage, directly or indirectly, as a reward intending that a relevant function will be performed improperly.

The offering of bribes could be considered as inducements to someone in a position of authority and trust in getting them to do something for the person offering the bribes, which they would not otherwise be entitled. The Bribery Act 2010 makes it an offence to accept or give or receive in kind inducements to receive favours. Notwithstanding this premise, supported by the Law, Vee and Skitmore (2003) opined that this is an area where there are seldom scenarios of ‘black and white’ but more so lots of cases where grey areas exist. This is related to the fact that persons in authority frequently receive what could be described as ‘gifts’ in the form of ‘hospitality’. The question therefore arises when does ‘gift giving’ become bribery. Some would argue that this depends on the extent and degree of such gifts or hospitality (Vee and Skitmore 2003). By way of examples, many organisations have policies on gifts and hospitality and have procedures in place which place limits on the value of such offerings. Other companies may have rules which places requirements on staff to declare anything that they receive from third parties. Notwithstanding, these management systems and procedures for dealing with gifts and hospitality, do rely on the interpretation and the discretion of the individuals receiving them. The aforementioned grey area that surrounds this subject matter, has forced some organisations to have a zero tolerance on any form of hospitality or receipt of gifts. This may be regarded as an extreme measure especially where with disciplinary measures for those who choose not to abide by the organisational mandate. However, some would argue that it is the only way to ensure that abuse of such offerings does not take place.

According to Johnson (1991), the following criteria has to apply for gifts or hospitality to be deemed the illegal act of bribery:

- The gift or hospitality must be of a non-token nature that it considered reasonable to provide the giver with privileged status or

- The beneficiary of the gift may consciously or otherwise to favour the interests of the gift giver.

Some organisations have allowed gifts to be received and gift making to their clients as long as the above two conditions have not been breached.

Bribery laws and associated ethical practices apply to all organisations and their employees. It also applies to senior managers who ‘turn a blind eye’, suppliers and potential suppliers. There are many different risk areas where bribery can frequently take place and where there are temptations for potential bribery in the construction industry. Procurement is one of these key risk areas especially when large multi-million-pound contracts are being awarded. There have been many international cases that have occurred and been widely publicised. The Sweett Group PLC is one such case where fines of £2.25m were imposed after a conviction under the Bribery Act. The details of the case are detailed below:

The Sweett Group PLC is not an isolated case and in recent years there have been many more examples. The individual consequences can have devastating effects on individuals and organisations. These include the following:

- Damage to reputation (personal and organisational)

- Liberty (maximum 10 years prison sentence)

- Financial implications (unlimited fines and compensation orders)

- Inability to participate in public contracts for organisations

According to Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre (GIACC 2008), in terms of learning lessons from previous examples of bribery, there may be a list of what to do and what not to do and these are contained in Table 5.2.

| Things to Do | Things Not to Do |

|---|---|

| Be aware and sensible | Be naive |

| Be transparent | Think you are doing the organisation a favour |

| Get authorisation |

Be prepared to accept anything without checking such as: Regulations Code of conduct Your line manager Independent advice |

| Apply the ‘sniff test’ | Do something which you would not want publicising |

5.8 Conflicts of Interest

An issue that has a link with corruption is a conflict of interest. According to Fewings (2009) a conflict of interest is ‘…the conflict where a single person has obligations to more than one party to the contract, or there is a clash of private or commercial interest with a person’s public position of trust’. Conflict of interest could be defined as an interest, which if pursued, could keep professionals from meeting one of their obligations. Sometimes conflicts of interest could relate to the right of an employee to refuse to conduct unethical behaviour. Such refusal could relate to an individual not wanting to partake in an activity that they regard as immoral or one that they believe is fundamentally wrong.

Notwithstanding the above definitions, a conflict of interest could also be defined as a clash of commercial and private interests by individuals who hold a position of authority and trust. It could also be synonymous with an individual who has interests or obligations to two or more parties to a contract. Sometimes large national or global consultancies find themselves in instances where they are representing two different organisations who may be involved in the same project or party to the same contract. In most cases, this may cause the consultancy to withdraw from one party to avoid becoming conflicted. Notwithstanding this more common scenario, it is sometimes commonplace for those same consultancies to accept both commissions and form a ‘Chinese wall’ between two parts of their organisation to deal separately with the two clients. There are ethical questions as to whether this type of practice is acceptable. What is of paramount importance in such scenarios is that their clients are consulted to make them aware of the possible conflict of interest and give them the powers to withdraw them from acting for a client in such cases. If their client’s approval is expressly given, then it is imperative that the Chinese wall maintains a completely independent position for both clients without collusion and even contact in some instances. Notwithstanding the above, most lawyers would not advocate the use of the same consultancy to represent two parties to the same contract. Afterall it could become very complicated and convoluted if there was a dispute between the two contracting parties and the same consultancy representing both parties was required to give evidence in court. The author is not aware of any such cases but with such a known risk, many consultancies should steer clear from such practices just in case to avoid potential reputational damage.

In some cases, client’s boundaries have become blurred when working with their supply chain and this can result in a conflict of interest. An example could be a client representative who asks a contractor that they have appointed and worked with on construction projects to price an extension on their own house. This request is not strictly speaking the client seeking a financial concession on this private work and as such they may believe that this is not unethical in any way. Possibly this could be a classic case of an ethical dilemma brought about by self-delusion as discussed in the last chapter. The fact that the client has chosen to use a known contractor who they hold influence over and who is reliant on them for work could be perceived to be morally wrong. The contractor may feel they cannot refuse to provide a quotation for the works but could also believe that they would be expected to undertake the work for a lower price than the market would dictate. This puts both the client and the contractor in a compromised position where favours are given and expected in return. Therein lies the real problem in this area in that, certainly in a business context, people do not normally do things for nothing and there is a reciprocal reward that is sought at a later stage. Using the same example this could involve an obligation for the client to provide the contractor with a future contract award. This notion is captured by the phrase ‘you stroke my back and I’ll stroke yours’. Accordingly, the safest position is to separate business and private dealings especially when you an individual is working from a position of authority and influence and ‘better to be safe than sorry’. Two different examples of conflicts of interest are described below:

5.9 Ethics and Negligence Linked to the Design and Construction of Buildings

Cases of negligence could be unearthed in the whistle-blowing procedures of organisations as discussed previously in Chapter 4. Such procedures are clearly designed to eliminate or reduce bad practices and short cuts that could lead to claims for damages against those organisations. Negligence in this regard could be described as:

The failure to exercise that degree of care which, in the circumstances, the law requires for the protection of those interests of other persons which may be injuriously affected by the wants of such care.

Delbridge et al. (2000)

The above quotation, in the context of negligence within the construction industry could be extremely relevant. Where contractors or designers have compromised the health, safety and well-being of individuals, including members of the public, this could have catastrophic results with potential loss of life. Some examples of catastrophic cases involving accusations of negligence are contained below:

The above examples are clearly related to negligence associated with design and construction flaws, but it is interesting to also consider ethics from a construction, health and safety at work perspective. This is particularly pertinent to the UK construction industry where 2019 annual figures from the Health and Safety Executive showed that 30 people were killed on construction sites between April 2018 and March 2019. The leading causes of construction worker deaths were falls from height, which continue to be the biggest cause of death on construction sites despite calls for more safety procedures in previous years. These cases in totality accounted for more than half of the construction death reported in 2019 and were followed by impact from objects and electrocution. An example of a health and safety case breach which transcended into criminal proceeding is detailed below:

The above case studies should provide the food for thought on how such blatant examples of negligence and unethical practices, with such obviously devastating consequences, should be avoided in the future. This area will be covered later in the book in Chapter 6 around regulation and governance of ethical standards and expectations to counter unethical behaviour.

5.10 Global Corruption in the Construction Industry

A study by Usman et al. (2012) looked at unethical practices in the management of construction projects in Nigeria. According to them approximately 10% of the value of construction projects undertaken by the government of Nigeria is used to bribe government officials as ‘kick backs’ for granting work orders. This has had the overall effect of influencing government officials to initiate some projects for the financial benefits they could benefit from in this regard. Whilst some would argue that this is accepted as normal practice in Nigeria it is nevertheless an illegal and highly immoral practice which needs to be outlawed and prevented from occurring. They are benefiting a small minority of influential people at the expense of most of the population and in the process adversely affecting the fortunes of the country.

A further study by Abdul-Rahman et al. (2007) presented findings against frequency of unethical conducts in the Malaysian construction industry. These are illustrated in Table 5.3 and grouped into 11 categories ranging from acts of under bidding to bribery in the extreme. They also classified these categories against a frequency scale, based on Never, Sometimes, Often and Very Often, for each of these practices to ascertain the scale of their occurrence. Their analysis found that the top two ranked most unethical practices, classified as an ‘Often’ occurrence, related to what could be described as serious unethical practices around under bidding, bribery and corruption. This could be regarded as quite controversial and damaging for the reputation of the construction industry, certainly within a Malaysian context. Moreover, the next three most ranked unethical conducts, based around negligence, claims and payment games were found to have occurred ‘Sometimes’.

Table 5.3 Ranking of unethical conduct by construction players (adapted from Abdul-Rahman et al. 2007). Rank No. 1 = Most frequent. Rank No. 11 = Least frequent.

| Categories of Unethical Conducts | Rank |

|---|---|

| Underbidding, bid shopping, bid cutting | 1 |

| Bribery, corruption | 2 |

| Negligence | 3 |

| Front loading, claim game | 4 |

| Payment game | 5 |

| Unfair and dishonest conduct, fraud | 6 |

| Collusion | 7 |

| Conflict of interest | 8 |

| Change order game | 9 |

| Cover pricing, withdrawal of tender | 10 |

| Compensation of tendering cost | 11 |

Each year Transparency International scores countries on how corrupt their public sectors are seen to be. It sends a powerful message and governments have been forced to take notice and act. Behind these numbers is the daily reality for people living in these countries. The index cannot capture the individual frustration of this reality but does capture the informed views of analysts, businesspeople and experts in countries around the world. The Construction Perception Index (CPI) scores and ranks countries and territories based on how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be by experts and business executives. It is a composite index, a combination of 13 surveys and assessments of corruption, collected by a variety of reputable institutions. The CPI is the most widely used indicator of corruption worldwide. The top 17 countries in the CPI survey for 2019 are shown in Table 5.4. These countries scored above 75 in their index, with Denmark and New Zealand topping the list of countries with scores of 87 and four others namely Finland, Singapore, Sweden and Switzerland scoring 85 or above. The UK came at rank number 15 with a score of 77. Moreover, the bottom 17 countries in the CPI are shown in Table 5.5. These countries scored a CPI of 20 or less and included those countries that had undergone political and economic turmoil in recent years, mostly resulting from wars and instability.

Table 5.4 Top 17 construction perception index (CPI) scores and rankings by country.

| Country | Ranking | CPI Score | Number of Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 1 | 87 | 8 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 87 | 8 |

| Finland | 3 | 86 | 8 |

| Singapore | 4 | 85 | 9 |

| Sweden | 4 | 85 | 8 |

| Switzerland | 4 | 85 | 7 |

| Norway | 7 | 84 | 7 |

| Netherlands | 8 | 82 | 8 |

| Germany | 9 | 80 | 8 |

| Luxemburg | 9 | 80 | 7 |

| Iceland | 11 | 78 | 7 |

| Australia | 12 | 77 | 9 |

| Austria | 12 | 77 | 8 |

| Canada | 12 | 77 | 8 |

| United Kingdom | 12 | 77 | 8 |

| Hong Kong | 16 | 76 | 8 |

| Belgium | 17 | 75 | 7 |

Table 5.5 Bottom 17 construction perception index (CPI) scores and rankings by country.

| Country | Ranking | CPI Score | Number of Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | 197 | 20 | 5 |

| Burundi | 197 | 20 | 6 |

| Congo | 199 | 19 | 6 |

| Turkmenistan | 199 | 19 | 5 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 201 | 18 | 9 |

| Guinea Bissau | 201 | 18 | 6 |

| Haiti | 201 | 18 | 6 |

| Libya | 201 | 18 | 5 |

| North Korea | 205 | 17 | 4 |

| Afghanistan | 206 | 16 | 5 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 206 | 16 | 4 |

| Sudan | 206 | 16 | 7 |

| Venezuela | 206 | 16 | 8 |

| Yemen | 210 | 15 | 7 |

| Syria | 211 | 13 | 5 |

| South Sudan | 212 | 12 | 5 |

| Somalia | 213 | 9 | 5 |

To reduce corruption and restore trust in politics, Transparency International recommends that governments:

- Reinforce checks and balances and promote separation of powers.

- Tackle preferential treatment to ensure budgets and public services are not driven by personal connections or biased towards special interests.

- Control political financing to prevent excessive money and influence in politics.

- Manage conflicts of interest and address ‘revolving doors’.

- Regulate lobbying activities by promoting open and meaningful access to decision making.

- Strengthen electoral integrity and prevent and sanction misinformation campaigns.

- Empower citizens and protect activists, whistle-blowers and journalists.

In any country, especially those experiencing a high level of development opportunities, it is imperative to have a high level of ethical standards in construction management, as clearly construction plays a major role in economic development. For this reason, construction professionals need to demonstrate and abide by a high standard of social responsibility and behaviour. This should extend to individual judgement, expertise and accountability with regard to the implementation and management of construction projects. In Malaysia, a governing body was established in partnership with stakeholders from industry, namely the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB). The aim of this board was designed to tackle unethical practices and promote good ethical values in the construction industry, and they have developed the Construction Industry Master Plan (CIMP) as a route map in this regard. The underlying aim of this revolved around improving service quality outcomes and professionalism for the benefit of all stakeholders and communities.

5.11 Effect of Unethical Practices and Corruption

Apart from human values and morality issues, there can be significant damage for organisations in terms of economic loss, lawsuits and settlements from ethical breaches. Costs to businesses from unethical practices and behaviours can also affect employee relationships, damage reputations and reducing employee productivity, creativity and loyalty (Weiss 2003). Within the context of the construction industry, one of the dilemmas and challenges is that firms solely focus on the ethical behaviours of their own organisation. Construction companies normally have large supply chains that have to be part of the business ethics model. For this reason, they sometimes have an ethical and moral responsibility for the behaviour of their suppliers, subcontractors and other stakeholders. This could provide a positive way of influencing other organisations down the chain for reforming and educating the construction industry.

According to Inuwa et al. (2015) there has been little research undertaken in the past relating to the effects of professional ethics on the performance of construction projects. In developing countries especially, there have been examples of corruption severely affecting the quality and in some cases compliance of buildings with current regulations. In some cases, this has resulted in adverse events as show in Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.5 Examples of adverse extreme events resulting from corruption.

In extreme events this has resulted in the following outcomes as show in Figure 5.6.

Figure 5.6 Examples of extreme negative events resulting from corruption.

5.12 Remedies for Unethical Behaviours and Corruption

A high level of professionalism is expected of construction professionals in discharging their duties and strictly adhering to ethical standards. However, this chapter has highlighted many different examples of unethical practices, arguably more frequent in developing countries, which can be very harmful to the outcome of construction projects and ultimately their respective economies (Inuwa et al. 2015).

In the case study of Nigeria, Inuwa et al. (2015) reported that there is a general lack of punishment for unethical practices including corruption and this is one of the major factors that has been responsible for the state of the construction industry. Other problems that have historically played a part in unethical practices include the lack of continuity in government programmes, loss of money through changes in government and political leadership and availability of loopholes in project monitoring. Causes of corruption can be exacerbated by factors such as greed, poverty, politics in the award of building contracts, professional indiscipline and favouritism. Inuwa et al. (2015) articulated that in such developing countries the construction industry is more susceptible to ethical problems than that of other industries. This could be explained by the value of the construction industry, and the potential financial benefits from corruption. There are also many different stages in the process from planning a project to completion on site, and each one has many different stakeholders involved who could participate in unethical practices. The tendering process has been long associated with corruption, especially where officials representing clients are empowered to award-building projects to contracts in exchange for bribes.

5.13 Summary

The construction industry provides a perfect environment for ethical dilemmas, with its low-price mentality, fierce competition and paper-thin margins. In addition, different cultures exist within the construction industry, and this may make boundaries between ethical and non-ethical behaviour become blurred at times. Categories of unethical behaviour could include breaches of confidence, conflicts of interest, fraudulent practices, deceit and trickery, presenting unrealistic promises, exaggerating expertise, concealing design and construction errors and overcharging. Less obvious examples of unethical behaviour could emanate from the misuse of power within organisations, and this could relate to managers making unfair or unreasonable demands on their subordinates, displaying intimidating behaviours or undermining their staff. There are degrees of understanding of what constitutes ethical compliance around regulations and rules, especially where tendering and procurement practices are concerned. Accordingly, one party may consider one practice to be acceptable and ethical, whereas another may find it totally unacceptable and unethical. This demonstrates that what constitutes unethical behaviour in practice is not always black and white and can come in many shades of grey owing to interpretation difficulties. This is particularly the case where gifts and corporate hospitality are concerned, albeit The Bribery Act 2010 does offer some clarity in the area; making it an offence to accept or give or receive in kind inducements to receive favours.

Some have argued that new players in the construction industry could be emerging with a general lack of appreciation of construction ethics. Notwithstanding this premise, causes of corruption can be exacerbated by factors such as greed, poverty, politics in the award of building contracts, professional indiscipline and favouritism. Corruption is particularly a problem in some developing countries where as much as 10% of total global construction expenditure was lost to some form of corruption. Notwithstanding this premise, corruption is not confined to developing countries and financial irregularities, scandals, blacklisting and what could the press have referred to as ‘dirty tricks’ have brought the UK construction industry into disrepute in recent years. Where corruption has occurred, it can be very damaging for the reputation of those organisations involved, especially where they have been found guilty of breaching ethical standards and committing criminal offences. Many cases of financial impropriety, false reporting and fraud have entered the courtroom sometimes resulting in fines, and in extreme cases imprisonment. The case of construction and professional services company Sweett Group PLC in February 2016 was one such example on a global scale, where they were ordered to pay £2.25m after a bribery conviction. Other non-fine–related consequences for unethical breaches could include damage to reputation (personal and organisational), liberty (maximum 10 years prison sentence) and the inability to participate in tendering for public contracts. It is perhaps not surprising that the reputation of the construction industry has been tarnished over many years, which has culminated in a general lack of public trust and confidence in some countries.

Conflicts of interests have links with corruption and occur where there is a clash of commercial and private interests by individuals who hold a position of authority and trust. It could also be synonymous with an individual who has interests or obligations to two or more parties to a contract. Negligence in the design and construction of buildings represents another type of unethical action. Where contractors or designers have compromised the health, safety and well-being of individuals, including members of the public, through poor design or construction quality this could have catastrophic results with potential loss of life. Some examples of such cases include the partial collapse of Ronan Point tower block in 1968 and more recently the devastating fire spread at Grenfell Tower in 2017.

To reduce corruption across the world and restore trust in politics, it is recommended that global governments reinforce checks and balances around financial auditing, promote separation of powers, tackle preferential treatment, reduce biased towards special interests and prevent excessive money and influence in politics. Finally, other recommendations include managing conflicts of interest, promoting open and meaningful access to decision-making and empowering citizens whilst protecting activists, whistle-blowers and journalists.

References

- Abdul-Rahman, H., Abd-Karim, S.B., Danuri, M.S.M., Berawi, M.A., and Wen Y.X. (2007). Does professional ethics affect construction quality? Quantity Surveying International Conference. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia . Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com [Accessed November 24th, 2019].

- Challender, J. (2019). The Client Role in Successful Construction Projects. London: Routledge.

- Daily Mail (2020). Grenfell builders shunned safer cladding to save cash. Daily Mail 24th October 2020.

- Daily Mail (2021a). Building firm’s £15bn bonanza since Grenfell. Daily Mail 6th January 2021.

- Daily Mail (2021b). Deadly secret of Grenfell firm’s panel test failures. Daily Mail 17th February 2021.

- Delbridge, A. and Bernard, J.R.L. (2000). Macquarie Dictionary, Macquarie Point.

- Fewings, P. (2009). Ethics for the Built Environment. Oxon: Taylor and Francis.

- GIACC Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre (2008). Examples of Corruption in Infrastructure Examples of corruption in infrastructure . from www.giaccentre.org [Retrieved November 6th, 2010].

- Inuwa, I.I., Usman, N.D., and Dantong, J.S.D. (2015). The effects of unethical professional practice on construction projects performance in Nigeria. African Journal of Applied Research (AJAR) 1 (1): 72–88.

- Liu, A.M.M., Fellows, R., and Nag, J. (2004). Surveyors’ perspectives on ethics in organisational culture. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 11 (6): 438–449.

- Stansbury, C.S. (2008). Examples of Corruption in Infrastruture. London: Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre.

- Usman, N.D., Inuwa, I.I., and Iro, A.I. (2012). The influence of unethical professional practices on the management of construction projects in northeastern states of Nigeria (3)2. 124–129.

- Vee, C. and Skitmore, M. (2003). Professional ethics in the construction industry. Engineering,Construction and Architectural Management 10 (2): 117–127.

- Walker, A. (2009). Project Management in Construction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Weiss, J.W. (2003). Business Ethics: A Stakeholder and Issues Management Approach, Third ed. Ohio: Thomson South-Western.