10

Codes of Conduct for Professional Ethics

There is only one ethics, one set of rules of morality, one code: that of individual behaviour in which the same rules apply to everyone alike.

Peter Drucker

10.1 Introduction to the Chapter

This chapter of the book will articulate why there needs to be ethical principles for those professional working in the construction industry and will explain the importance of such principles. It will also highlight the challenges for ethical teaching given that there are no universal standards around the world and between different professional institutions on what constitutes good ethical practices.

The chapter will explain codes of conduct in regulating professional ethics, what these comprise and how they are applied to improve practices and behaviours. In this regard it will discuss the benefits of having codes of conduct and how they vary between different professional bodies and institutions. Penalties and sanction for non-adherence and breaches of professional codes of conduct will be covered in the chapter alongside implications for public trust and confidence for violations of ethical regulations. Alongside this, the importance of maintaining public trust will be discussed given that the construction industry has traditionally been regarded in poorly performing in the past with low levels of client satisfaction. Conversely the reputational benefits of strict compliance with institutional codes of conduct will be articulated and why these are important for maintaining professional standards.

Embedding codes of conduct and ethical behaviours and standards into organisational culture by professional bodies will be examined alongside the factors which are influential for promoting best practices. In this regard strategies and models will be identified and discussed how they are maintained within organisations. Finally, comparisons of many professional bodies will be made in there approaches to professional ethics, standards and behaviours and the differences between their codes of conduct.

10.2 Ethical Principles for Construction Professionals

Owing to increasing concerns in many high-profile cases including those previously referred to in Chapter 5 of this book, demonstrating dishonesty and corruption, it is important for construction professionals to commit to and encourage project teams to comply with sustainable ethical principles. Codes of ethics which have been introduced have provided an indicator that organisations and institutions take ethical principles seriously as they should outline expectations for all personnel with regard to ethical behaviour and intolerance of unethical practices (CMI 2013).

Relationships between construction clients and the professional consultants and contractors they appoint rely on professional ethics and trust especially since fee agreements cannot accurately specify all financial contract contingencies for possible additional services (Walker 2009). The main motivation for the public relying on members of professional bodies relates to them giving advice and practising in an ethical manner (RICS 2010). Accordingly, the RICS has developed 12 ethical principles to assist their members in maintaining professionalism and these relate to honesty, openness, transparency, accountability, objectivity, setting a good example, acting within one’s own limitations and having the courage to make a stand. In order to maintain the integrity of the profession, members are expected to have full commitment to these values.

Arguably the main deficiencies of codes of ethics had emanated from the notion that there are no universal standards and accordingly they vary between countries and different sectors in the building industry. Boundaries and barriers created by fragmentation and differentiation within the construction sector have possibly deterred any common frameworks of professional ethics emerging in the past (Walker 2009). This is an area that demands more attention through multinational dialogue across all areas of the construction sector, to overcome.

10.3 Codes of Conduct to Regulate Professional Ethics

Members of professional bodies are bound by codes of ethics, sometimes referred to as ethical principles, to address the issue of non-ethical behaviour and to attempt to provide a context of governance (Liu et al. 2004). Members of such institutions are usually bound by codes of conduct in the way they practice, and the institutions reserve the rights to take action against members who breach rules and regulations laid down. A professional code of conduct could be described as a minimum level of behaviour which is expected of an individual member of a profession. Normally such behaviour relates to professional practice and compliance with institutional rules and regulate and the intention is to preserve the reputation and good name of a profession through self-governance.

Almost every profession has its codes of conduct to provide a framework for arriving at good ethical choices (Abdul Rahman et al. 2007). In the United Kingdom and indeed worldwide, construction industry professionals have qualifying and professional institutions and bodies that represent each discipline such as RIBA, CIAT, CMI, RICS, CIOB and many more. These institutions have strict charters, professional codes of conduct and ethics, rules and regulations relating to professional standards that individual members are required to follow and adhere to. These may differ in some details from one institute to another, but the majority of them do require members to act professionally and use and apply common ethical and moral principles for conducting business. Professional institutions who introduce and administer the codes of conduct for their members will normally enforce sanctions and disciplinary action on their members for non-compliance. If these individuals fall short of the required standards, they could be subject to a disciplinary committee who in some cases could expel them. For serious cases possibly involving illegal activity, e.g. fraud the institution, could report the perpetrators to the relevant authorities for further action.

Most Institutes and organisations have separated codes of ethics from codes of conducts, and some like Chartered Management Institute (CMI) defines its codes of ethics as ‘a statement of the core values of an organisation and of the principles which guide the conduct and behaviour of the organisation and its employees in all their business activities’ (CMI 2010). One of the reasons that code of professional conduct is applied is to promote good conduct and best practice (RIBA 2005).

It is normal for professions such as the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors to enforce mandatory continuous professional development (CPD) on their members to ensure they keep abreast of skills, education and regulations. These are linked to the professional institutions’ ethical commitments to keep their members attuned to new developments in the sector, especially around their specialist areas of competence and experience. Some of the criticism of codes of conduct have in the past been voiced at the constraints and limits of the codes and the ability to manage behaviours, especially in the construction industry.

Technological and scientific advances in recent decades have led to continued requirements for the review, update and introduction of new codes of conduct by institutions and organisations. Such measures are required in order to respond to changes to aspects of human activities and environmental changes such as global warming and other environmental issues. The construction industry arguably has more relevant to environmental issues than those of other sectors, possibly due to the building process which have traditionally been heavy on carbon generation. In addition, in recent years there has been an increased focus on the construction life cycle costs of building, and so energy efficiency and use of renewable technologies has become more important.

It is important for construction professionals to be aware that adopting the aforementioned codes of conduct gains and maintains respectability and integrity for project teams, and their respective professional institutions and organisations (Vee and Skitmore 2003). Stewart (1995), however, was sceptical of such institutional codes of conduct and explained that these are merely guidelines for professionals to interpret as they wish and do not promote values, ethics and morality accordingly. Clearly corrupt behaviour is subject to more than just policing by professional institutions and in some cases can be deemed criminal offences. This being the case, there is a strong argument to suggest that the law, coupled with institutional sanctions may present an acceptable level of deterrent in that professionals will think twice before committing unethical behaviour if consequences are considered grave enough. Lui et al. (2004) argued, however, that transgression will still prevail if detection of breaches is considered unlikely or disciplinary measures imposed for breaches are regarded as insufficient or too lenient. Conversely, there is an argument that ethical codes of conduct should not be regarded negatively as a framework for punishing breaches but positively in assisting professionals in recognising their own moral parameters (Henry 1995). Accordingly, this raises the question of the role of codes of conduct and whether their purpose should be more closely linked to promoting compliance. This could involve motivating professionals to behave in an ethical manner as opposed to them be seen as frameworks to impose punishments for potential breaches.

Sometimes professional bodies may be accused of compromising governance matters linked with their own codes of conduct. The Independent Review of RICS Treasury Management Audit Issues (RICS 2021) found that the origins of what went wrong within the RICS between 2018 and 2019 laid in the governance architecture of the institution. A lack of clarity about the roles and responsibilities of the Boards, the senior leadership and the management left cracks within which the Chief Executive and his Chief Operating Officer had become used to operating with little effective scrutiny. The release of the report on 9th September 2021 culminated in senior leaders with the RICS stepping down including the Chief Executive, President, Interim Chair of Governing Council and Chair of the Management Board. The 467-page report concluded that 4 non-Executive Board members, who raised legitimate concerns that the audit had been suppressed, were wrongly dismissed from the Management Board and that sound governance principles were not followed.

10.4 Maintaining High Standards of Professional Conduct and Competence

When considering codes of conduct, one needs to determine not only the particulars relating to as particular code but the context of what the code is intended for and the capability to comply with it. Introducing codes of conduct, codes of ethics, rules and regulations by professional institutions is a strong message and indication to members on what is expected of them in terms of behaviour. It also sends a strong signal to other stakeholders that unethical practices will not be tolerated (Fewings 2009).

Codes of conduct developed by professional institutions are designed to provide a strict code of adherence to ethical values whereupon the interests of communities and clients take priority over self-interests of individuals belonging to those professions (Haralambos and Heald 1982). For this reason, the primary reason for having codes of conduct are to ensure and embed governance and regulation of professional ethics. This is an important focus for the book when considering that relationships between clients and their professional contributors has relied in the past on a significant level of trust and professional ethics (Walker 2009). Furthermore, the heart of best practice in construction management is the maintenance of high standards of professional conduct and competence, underpinned by the principles of honesty and integrity (CMI 2010). This view was reinforced by Vee and Skitmore (2003) and they articulated the importance of codes of conduct as the tool to enable such standards. They argued that construction professionals should have the fundamental commitment to professional conscience and professional competence. Professional competence in this context can be defined as the capability to perform the duties of one’s profession generally, or to perform a particular professional task with skill of an acceptable quality (Vee and Skitmore 2003). Furthermore, professional competence is predicated on having the broad skills, attitude and knowledge to work in a specialised profession or area. Disciplinary knowledge and the application of concepts, processes and skills are required as the measure of professional competence in any particular field. Professional competency is one of the five fundamental principles of professional ethics along with integrity, confidentiality, professional behaviour and objectivity. Notwithstanding this, each of the professional institutions have their own lists of technical and professional competencies, which are closely aligned to their institutional rules and regulations.

Another important role for codes of conduct, according to Lere and Gaumnitz (2003) is to influence decision making. Notwithstanding this assertion, the problem has been to establish those codes of ethics which are most effective at promoting ethical decision making. This involves determining those codes of ethics that impact decision making to the effect that they change the values and beliefs of individuals. Furthermore, according to Inuwa et al. (2015) codes of conduct are to ensure clients’ interests are properly cared for, whilst wider public interest is also registered and protected. The RICS have articulated that as client’s expectations have changed, business practices need to change also to respond to these. This could mean that ethical issues need to feature highly on the list of organisational strategies and business drivers. Codes of ethics established by professional institutions such as the RICS can serve as ‘checks and balances’ for individual members to try to curb unethical or immoral behaviours. This could assist in reducing the undesirable practices and behaviours on a global level.

10.5 Governance and Enforcement of Professional Ethics through Codes of Conduct

In practice, as previously referred to, professional ethics are policed by a national or international body to ensure a minimum standard of practice for organisations to strictly adhere to. Such bodies are most frequently professional institutions that seek to ensure that the behaviour of construction professionals is controlled and monitored by a strict code of ethics, which they create and maintain (RICS 2001). These codes of ethics, frequently referred to as codes of conduct, are primarily to ensure that integrity and ethics are maintained at all times. Institutions such as the RICS and RIBA have royal charters which strictly set down rules and regulations relating to professional standards, moral and ethics which all members must comply with. Members of professional bodies are bound by codes of conduct to address the issue of non-ethical behaviour and to attempt to provide a context of governance (Liu et al. 2004). Members of such institutions are then bound by such codes of conduct in the way they practice, and the institutions reserve the rights to take action against members who breach rules and regulations laid down.

Professional ethics through the aforementioned codes of conduct set down acceptable norms and thresholds relating to standards of practice. This creates ethical codes, codes of conduct and sets of rules by which member individuals or organisations are regulated. Furthermore, measures are taken to give more transparency relating to investigation of what could be deemed as behaviour or actions of an unethical nature. This adds robustness and due diligence to the process and could have the effect of boosting public confidence. Codes of conduct can sometimes be synonymous with rules to deal with certain issues and particular situations. Examples could include members of a professional institution maintaining indemnity insurance and processes for reporting malpractice of fellow members. The institutional rules and regulations more often than not cover potential conflicts of interest at an individual or corporate level. This would normally apply where a person or organisation has obligations to more than one party on a commission or contract and from wit her a private or commercial standpoint there is a clash of interests. This has to be considered from the position of trust that lies with that particular individual or organisation and measures to ensure that others are not disadvantages by a lack of impartiality.

There can be deterrents to avoid or reduce unethical behaviours and adherence with codes of conduct and these can be intrinsic to individuals. However, professional institutions or organisations can also impose extrinsic deterrents to such behaviours through enforcement provisions, and these may be made compulsory or voluntary. Individuals will still decide themselves whether to comply with such codes and so they cannot be forced to comply with them. However, professional institutions or organisations can impose strict penalties for codes which are violated. The degree to which individuals view such penalties will affect the extent to which they comply. For instance, if individuals regard the penalties as having negative consequences for them, then they will be more likely to comply and the codes in such cases become compulsory for them. Examples of such penalties could be instant dismissal from an organisation or expulsion from a professional institution. Alternatively, the decision makers regard the penalties as less serious for them, then even the largest penalties may not make compliance compulsory.

It is important for construction professionals to be aware that adopting codes of conduct, gains and maintains respectability and integrity for project teams, and their respective professional institutions and organisations (Vee and Skitmore 2003). Stewart (1995), however, was sceptical of such institutional codes of conduct and explained that these are merely guidelines for professionals to interpret as they wish and do not promote values, ethics and morality accordingly. Clearly corrupt behaviour is subject to more than just policing by professional institutions and in some cases can be deemed criminal offences. This being the case, there is a strong argument to suggest that the law, coupled with institutional sanctions, may present an acceptable level of deterrent in that professionals will think twice before committing unethical behaviour if consequences are considered grave enough. Liu et al. (2004) argued, however, that transgression will still prevail if detection of breaches is considered unlikely or disciplinary measures imposed for breaches are regarded as insufficient or too lenient. Conversely, there is an argument that ethical codes of conduct should not be regarded negatively as a framework for punishing breaches but positively in assisting professionals in recognising their own moral parameters (Henry 1995). Accordingly, this raises the question of the role of codes of conduct and whether their purpose should be more closely linked to promoting compliance. This could involve motivating professionals to behave in an ethical manner as opposed to them be seen as frameworks to impose punishments for potential breaches.

10.6 Misconduct and the Reputation of Professions

Construction projects have traditionally had a reputation for poor performance, coupled with low levels of client satisfaction (Latham 1994). Poon (2003) argued that there is a specific lack of research into the ethical issues of construction management that could be resulting in less than satisfactory project outcomes. This is especially the case as professionals rely on both knowledge and ethical conduct for the general public to have confidence in them. For a professional institution to gain public confidence in this regard, maintaining ethical practices are very important, as they have a direct influence on quality of those services provided to clients and the public image and perception.

Where misconduct and unprofessional behaviours have been identified in the past, this has had negative implications on the way the construction industry has been viewed. In some cases, this has led to public concern and government attention. Conversely, where there is deemed to be a high level of ethical practices adopted and adhered to by a profession, then this would normally imply high performance and low client dissatisfaction levels. When specifically considering the surveying profession one needs to consider those services not specifically related to construction projects but the whole diverse range of property services across the spectrum across the life cycle of buildings. In the past the RICS has focused on trying to improve the reputation of the institution in this regard and distinguish it from other services such as estate agency. This was in a concerted effort to improve trust amongst the public in light of cases of some cases of professional misconduct. Notwithstanding this position, Poon (2003) argued that the focus for training surveyors has traditionally been linked to providing core skills and ‘hands on’ knowledge required to perform their services. Such priorities are not always focused on improving the quality of those services provided and ethical considerations in some cases has been regarded as a sub-strand to working practices rather than a foundation those services are built up on. Perhaps this explains why in the past there have been calls for reforms to training and education programmes for surveyors and how these may assist in improving quality levels.

10.7 Embedding Ethical Codes, Behaviours and Standards into Organisational Culture

Liu et al. (2004) argued that in the construction industry there has been a focus in the past on culturally related attributes of project teams and a general commitment to quality. Notwithstanding this premise, they concurred that there has been evidence to suggest that ethical behaviours and standards are responsible for successful project outcomes.

Professional ethics can be reinforced through professional standards of professional bodies and codes of practice to gain respectability and integrity. However, these codes and standards need to be embodied in management practices and roles and responsibilities assigned to ensure compliance across ethics programmes. As such these codes are insufficient in themselves to ensure ethical conduct and accordingly require to be complemented with organisational responsibilities and employer training programmes. Such positions as ethics officers could be instrumental in ‘turning the tide’ in bringing ethics and ethical values to the forefront of organisational values. Such interventions and measures could shape how organisations are structured and how they function and bring reputational benefits for them. A survey carried out by Vee and Skitmore (2003), of construction professionals in Australia, found that most companies (90%) had subscribed to a professional code of ethics, albeit only 45% had ‘gone the extra mile’ and committed to ethical codes of conduct. Most of the organisations and individual who contributed to the survey agreed that ethical practice is considered to be an important goal for their respective organisations. Furthermore, most of them reinforced the perspective that business ethics should be governed and driven forward by personal ethics.

Professional codes of practice and conduct are committed to by members of institutions as a prerequisite for being a member of that institution. According to Stewart (1995) they should, however, not be used to teach ethics, values or morality. They simply are there to lay down rules of conduct as guidelines for action. Enforcement of the codes can be an important factor, and if there are little or no consequences, then it is unlikely that individuals will always act in the way that a particular institution intends. However, when consequences are grave for a particular breach people will think twice before infringing ethical codes of conduct. A similar phenomenon is apparent when the risk of detection of breaches is low. If individuals believe they can breach ethical codes of conduct and get away with it, with little chance of being found out, then it is more likely that they will commit unethical practices. In this case it can create an environment of opportunism where ethical behaviours are heavily influenced by the organisation. In this way ethical practices and behaviours can be delineated by the climate and culture of the organisations and the boundaries of socially acceptable norms that they operate. Ethical codes do not in themselves always solve moral dilemmas or reduce instances of illegal practices. However, they work best where they are supported by mechanisms and structures that ensure review, adjudication, communication, oversight, review and enforcement.

Liu et al. (2004) created an organisational ethics model, particularly focused on the perspectives of surveyors and data obtained from Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors (HKIS). It analysed several factors under the categories of ethical climate, culture and codes to assess which of the factors were more influential and important in promoting ethical standards and behaviours than others. These are listed in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Model of ethical climate, culture and codes (adapted from Lui et al. 2004).

It was concluded from the research by Vee and Skitmore (2003) that from the perspective of surveyors the dominant factor in both the public and private sectors was Laws and Professional Codes. This was related to surveyors, as professional practitioners, being more conformant to professional institutional standards which act as behavioural norms for them to practice within. Furthermore, the study showed that ethical codes are more effectively implemented in the public sector, where financial and behavioural governance play a very important role in organisational management. These codes are deemed to be less clear in the private sector where their use in some cases could be more related to enhancement of reputation and image. For codes to be effective, it is crucial for them to be communicated down throughout the whole organisation.

10.8 Strategies for Improving Codes of Ethics Implementation in Construction Organisations

At an operational and corporate level within the construction industry there have been widespread and frequent problems in the past associated with business ethics. According to Kilcullen and Kooistra (as cited in Oladinrin and Man-Fong Ho 2014) business ethics are defined as ‘a set of principles that guide business practices to reflect a concern for society as a whole while pursuing profits’. Accordingly, codes of ethics could be described as written organisational policy commitments to ethical conduct. Some examples of unethical practices which was covered in earlier chapters include mismanagement of client resources, poor quality of work and services, improper tender practices, bid cutting, collusion in tendering and improper relations with clients. In the past there have been attempts to explain how and why these practices and behaviours have been allowed to become commonplace. Possible reasons suggested by Oladinrin and Man-Fong Ho (2014) could include deficiencies in ethical codes of conduct embodiment within organisations and ineffective corporate code implementation. The presence of codes of ethics within organisations on their own are not sufficient to ensure that ethical practices and behaviours prosper.

One needs to consider how codes are implemented and thereafter how they are maintained within organisations, especially given that the global construction industry has been characterised in the past as having a poor ethical culture. Figure 10.2 illustrates some areas of implementation in this regard as devised by Svensson et al. (2009, as cited in Oladinrin and Man-Fong Ho 2014). These include ethical tools, ethical bodies, ethical support procedures and ethical usage.

Figure 10.2 Areas of implementation of ethical codes (adapted from Svensson et al. 2009).

These areas should be embedded into the structure and operation of organisations processes and procedures. Measures under each of these areas should include setting up of ethics committees and ombudsman, ethical training, conducting audits, communication with staff on ethical dilemmas and monitoring compliance with ethical codes. There have been other processes for implementation of ethics and the International Project Management Association (IPMA) have advocated and adopted the European Foundation for Quality Management Model (EFQM) in this regard. This is illustrated in Figure 10.3, and it is comprised of key component which are classified as enablers to implementing and embedding codes of ethics into organisations. Such enablers include processes, policy and strategy, leadership, partnerships and resources and people/employee management.

Figure 10.3 Enablers for implementation and embedding of codes of ethics (adapted from Svensson et al. 2009).

Each of these enablers would include six criterion each which represent attributes to stimulate ethical behaviours and improve ethical practices by embedding such codes. Leadership is regarded as being an important enabler as part of the EFQM model. Managers as leaders in their respective organisations are regarded as change agents, crucial to reshaping working practices and reforming cultures from the top down. This involvement of senior management is seen as paramount given that evidence has shown that ethical malpractice has resulted in the reputation of the construction industry being damaged. Accordingly, measures to correct this need to flow from top management with dedication and readiness to address breaches and instil an environment of integrity and due diligence. In addition, it is crucial to have the right and most appropriate strategies and policies in place, as these are regarded as providing the means to deliver missions and visions on ethical reform. These should be supported by the relevant plans, targets, regulatory guidelines for implementing codes of ethics centred on stakeholders’ requirements (Oladinrin and Man-Fong Ho 2014). It is accepted, however, that procedures, processes and regulatory guidelines on their own will not be sufficient without the commitment of employees. For this reason, the importance of human factors cannot be underplayed, especially as staff are positioned at the heart of any organisation and arguably their most important asset. According to Oladinrin and Man-Fong Ho (2014) is the ‘people enabler’ that provide the means for human resource management at all levels within organisations. Measures that could be implemented in this regard could include communication of codes, whistle-blowing protection procedures, appraisal of staff, reward systems and employee self-evaluation. The EFQM also recognises that managing ethics goes beyond the boundaries of organisations and extends to their stakeholders and wider supply chain. The importance of ensure the ethical compliance of subcontractors, suppliers and any other stakeholders that organisations contract within their business dealings is crucial. Accordingly, organisation need to be mindful how they approach the issue of their project participants and external partnerships in terms of their ethical policies and strategies.

10.9 Developing a Model Code of Conduct

Codes of conduct are sometimes anchored around the Seven Nolan Principles and embedded as core requirements for organisational financial regulations. According to Fewings (2009) these principles are detailed in Figure 10.4.

Figure 10.4 The Seven Nolan Principles. Fewings, P. 2009 / Taylor & Francis.

The National Governance Association (NGA) have devised and advocate their Model Code of Conduct for Governing Boards (2019) which is based around the Seven Nolan Principles. They concur that:

The NGA model is designed to help boards draft a code of conduct which sets out the purpose of the boards and which describes the appropriate relationship between individuals, the whole board and the leadership team of organisations. It should be noted that these codes of conduct can be tailored to reflect the specific governing board of particular organisations.

10.10 Chartered Management Institute (CMI) Codes of Ethics Checklist

A ‘Code of Ethics Checklist’ published by the Chartered Management Institute CMI sets down that ethics is particularly relevant to maintaining the reputation of an organisation and inspiring public confidence in it (CMI 2013). For this reason, codes of ethics should reflect the practices and cultures which construction clients want to encourage for their respective organisations and project teams. This is supported by the CMI who advocated that:

A code of ethics is a statement of core values of an organisation and of the principles which guide the conduct and behaviour of the organisation and its employees in all their business activities.

CMI (2013)

In the context of some high-profile cases of unethical behaviour, sometimes involving fraud it is becoming ever increasingly important for firms to fulfill their commitments to ethical business principles. The Code of Ethics Checklist provides clear guidance for employees on what is expected of them in terms of ethical behaviours and practices. This sends a clear signal to other parties including customers and suppliers that unethical practices are not acceptable. The CMI articulates that a code of ethics must be more than just a document. They conclude that it should represent the culture and practice of an organisation and be arrived at through consultation and involvement with staff at all levels within an organisation. The action checklist is shown in Figure 10.5.

Figure 10.5 The Code of Ethics Checklist.

CMI advise that organisations should avoid ignoring the code once it has been introduced, so that it becomes worthless. They also concluded that it should not be used to impose inappropriate values and should not be regarded as a one-off rather than continuous commitment. They concur that it should not be a document that is confusing, vague, ambiguous and not comprehensible and in its creation should involve staff in the process of creating or revising the code.

10.11 The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) Codes of Conduct

The RICS have defined ethics as far as their institution around a set of moral principles and the notion of ‘securing clients interest’. They have established an RICS Professional Ethics Working Party which emphasised the importance of ensuring that the interests of clients are adequately maintained and cared for whilst recognising and respecting the interest of the wider public (RICS 2000). The RICS administer the conduct of their members through the establishment of a set of Rules of Conduct which they stress all members must strictly adhere to, and these have over many years been regularly updated in line with the changing social environment. They cover such areas as conflicts of interest, professional indemnity insurance, professional and personal standards, rules on accounting, lifelong learning and disciplinary procedures. To assist in compliance, they have also published guidance documents with practical recommendations for setting up and governance of surveying practices, procedures for handling complaints, protection against money laundering and management of client confidentiality. The RICS have established nine core ethical principles in conjunction with the aforementioned Rules of Conduct and these are designed to assist members in certain challenging scenarios. These offer helpful guidance on ways and means to manage those difficult circumstances where members’ professionalism may otherwise be compromised. In this way the RICS argue that there is less risk that members will breach ethical standards and therein improve the reputation of the institution and its members. The nine principles are illustrated in Figure 10.6. The nine RICS principles, coupled with the RICS Codes of Conduct, should together ensure that those professional services performed by surveyors are provided to their clients to maintain their interests at all times whilst preserving professionalism and the interests of the wider public.

Figure 10.6 The nine RICS ethical principles (adapted from RICS 2010).

The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors in their publication Maintaining Professional and Ethical Standards articulates that ‘every member shall conduct themselves in a manner befitting membership of the RICS’. To support this, they advocate that ‘members shall at all times should act with integrity and avoid conflicts of interest and avoid actions or situations that are inconsistent with their professional obligations’.

The RICS advocate that behaving ethically is at the heart of what it means to be a professional; it distinguishes professionals from others in the workplace. Furthermore, they require their members to demonstrate their commitment to ethical behaviour by adhering to five global professional and ethical standards and these are:

- Act with integrity. Be honest and straightforward in all that you do

- Always provide a high standard of service

- Act in a way that promotes trust in the profession

- Treat others with respect

- Take responsibility

The RICS have published regulations and guidance notes for clarity on each one of these standards and these are contained in Appendix I.

The RICS Codes of Conduct, in Table 10.1, are built up on the foundations of this commitment to professionalism and lists practical measures to ensure compliance in this regard. They deal with issues which include conflicts of interest, corruption, confidentiality, honesty and integrity. Members of the institution are then bound by such codes of conduct in the way they practice, and the institutions reserve the rights to take action against members who breach rules and regulations laid down. To put this into context the RICS Professional Regulation and Consumer Protection Department have in the past dealt with approximately 21000 cases of professional misconduct mostly related to breaches in regulations, conflicts of interest and accounts breaches (RICS 2010).

Table 10.1 RICS Codes of Conduct.

| RICS Codes of Conduct | Measures to Ensure Compliance |

|---|---|

| Act honourably | Never put your own gain above the welfare of your clients or others to whom you have a professional responsibility. Always consider the wider interests of society in your judgements. |

| Act with integrity | Be trustworthy in all that you do – never deliberately mislead, whether by withholding or distorting information. |

| Be open and transparent in your dealings | Share the full facts with your clients, making things as plain and intelligible as possible. |

| Be accountable for all your actions | Take full responsibility for your actions and don’t blame others if things go wrong. |

| Know and act within your limitations |

Be aware of the limits of your competence and don’t be tempted to work beyond these. Never commit to more than you can deliver. |

| Be objective at all times | Give clear and appropriate advice. Never let sentiments or your own interests cloud your judgement. |

| Always treat others with respect | Never discriminate against others. |

| Set a good example | Remember that both your public and private behaviour could affect your own, RICS’ and other members’ reputations. |

| Have the courage to make a stand | Be prepared to act if you suspect a risk to safety or malpractice of any sort. |

| Comply with relevant laws and regulations | Avoid any action, illegal or litigious, that may bring the profession into disrepute. |

| Avoid conflicts of interest | Declare any potential conflicts of interest, personal or professional, to all relevant parties. |

| Respect confidentiality | Maintain the confidentiality of your clients’ affairs. Never divulge information to others unless it is necessary. |

To support their Codes of Conduct and Professional and Ethical Standards, the RICS have quite helpfully created a decision tree for proceeding or not proceeding with certain courses of action, and for decision making in these situations. This is contained in Figure 10.7 and carefully navigates members through potential ethical dilemmas that they may face in the course of their business dealings.

Figure 10.7 Decision tree for proceeding or not proceeding with certain courses of action (adapted from RICS 2010).

The RICS have also created a Frequently Asked Questions document linked to their Global Professional and Ethical Standards and this is contained in Appendix J. Furthermore, the RICS has regulations which sets down rules in the event that an organisation ceases to trade, in such circumstances related to maintaining professional indemnity, handling complaints and managing clients’ monies. In the former case, professional indemnity ‘run off’ cover needs to be maintained for a minimum of six years following trading. This is to ensure that members and their organisations are not exposed to claims during this period. In the case of handling complaints, members should adopt an effective procedure for handling complaints prior to their organisation ceasing to trade. They should also ensure that clients’ monies are preserved until all monies have been distributed. There is also the RICS Clients’ Money Protection Scheme which provides robust governance in this regard.

10.12 The Royal Institution of British Architects Codes of Conduct

The Royal Institution of British Architects (RIBA) have three principles for their members to strictly adhere to and these are honesty and integrity, competency and relationship. These are built upon the institutional values of concern for others, environment, honesty, integrity and competency (RIBA 2005). These principles are contained in their Code of Conduct in Table 10.2 and are supported by clear rules and regulations around competition, advertising, insurance, complaints and dispute resolution. In addition, the RIBA provide guidance notes covering aspects as maintaining integrity and confidentiality. The Institute has Disciplinary Procedure Regulations that it administers, specifically related for breaches of ethical principles and regulations. It imposes disciplinary measures for contraventions according to the code and professional misconduct can be dealt with through sanction powers and a RIBA hearing panel.

Table 10.2 Code of Conduct; The Royal Institution of British Architects.

|

|

1.1 The Royal Institute expects its Members to act with impartiality, responsibility and truthfulness at all times in their professional and business activities. 1.2 Members should not allow themselves to be improperly influenced either by their own, other’s, self-interest. 1.3 Members should not be party to any statement which they know to be untrue, misleading, unfair to others or contrary to their own professional knowledge. 1.4 Members should avoid conflicts of interest. If a conflict arises, they should declare it to those parties affected and either remove its cause or withdraw from that situation. |

| 1.5 Members should respect confidentiality and privacy of others. |

| 1.6 Members should not offer or take bribes in connection with their professional work. |

|

| 2.1 Members are expected to apply high standards of skill, knowledge and care in all their work. They must apply their informed and impartial judgement in reaching any decisions, which may require members to balance differing and sometimes opposing demands (for example, the stakeholders’ interests with the community’s and project’s capital costs with its overall performance). |

| 2.2 Members should realistically appraise their ability to undertake and achieve any proposed work. They should also make their clients aware of the likelihood of achieving the client’s requirements and aspirations. If members feel they are unable to comply, they should not quote for, or accept, the work. |

| 2.3 Members should ensure that their terms of appointment, the scope of their work and the essential project requirements are clear and recorded in writing. They should explain to their clients the implication of any conditions of engagement and how their fees are to be calculated and charged. Members should maintain appropriate records throughout their engagement. |

| 2.4 Members should keep their clients informed of the progress of a project and of the key decision made on behalf of the client. |

| 2.5 Members are expected to use their best endeavours to meet the client’s agreed time, cost and quality requirements for the project. |

|

| 3.1 Members should respect the beliefs and opinions of other people, recognise social diversity and treat everyone fairly. They should also have a proper concern and due regard for the effect that their work may have on its users and the local community. |

| 3.2 Members should be aware of the environmental impact of their work. |

| 3.3 Members are expected to comply with good employment practice and the RIBA Employment Policy, in their capacity as an employer or an employee. |

| 3.4 Where members are engaged in any form of competition to win work or awards, they should act fairly and honestly with potential clients and competitors. Any competition process in which they are participating must be known to be reasonable, transparent and impartial. If members find this not to be the case, they should endeavour to rectify the competition process or withdraw. |

| 3.5 Members are expected to have in place (or have access to) effective procedures for dealing promptly and appropriately with disputes and complaints. |

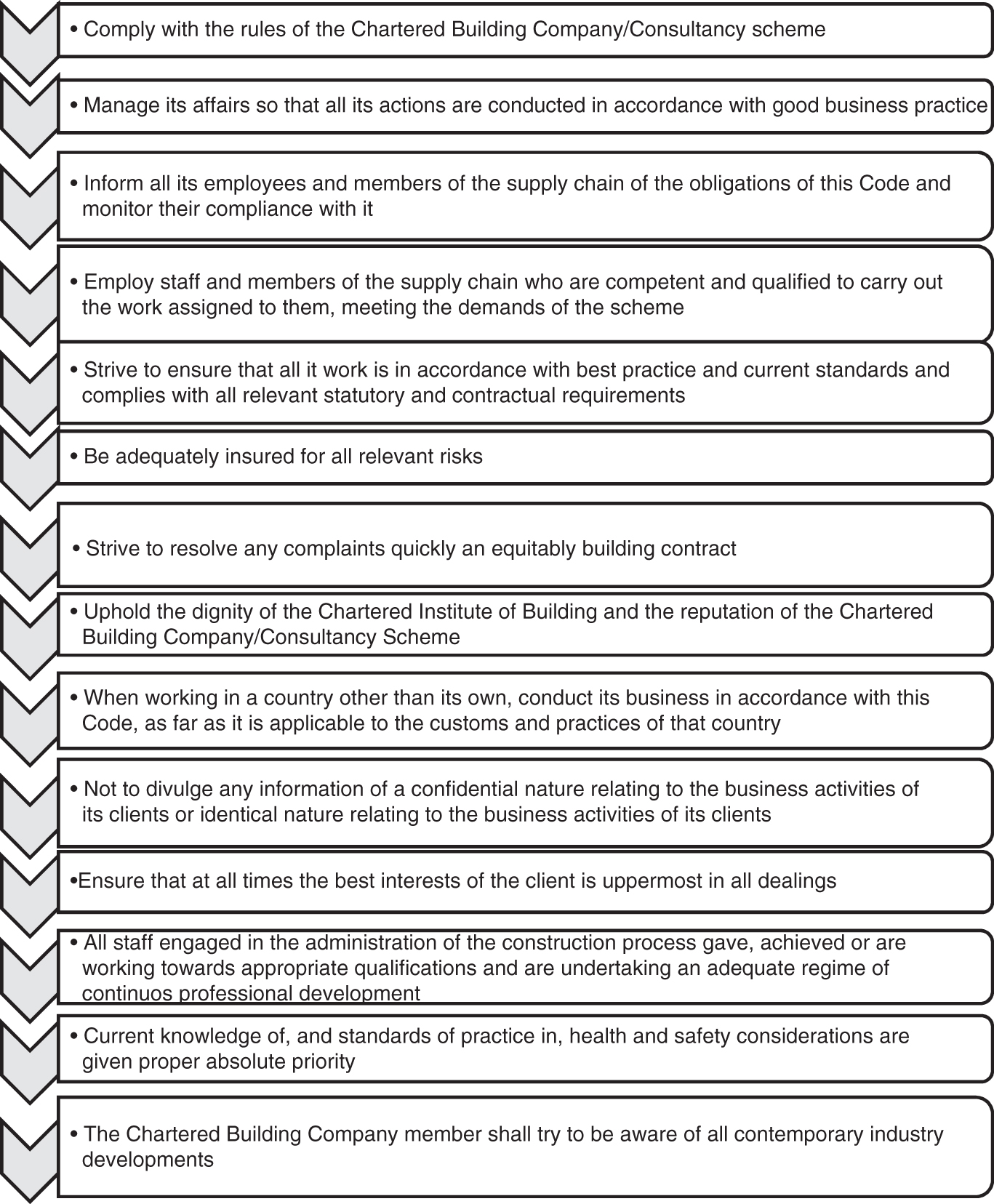

10.13 The Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB) Codes of Conduct

The Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB) sets down its codes of professional conduct based on the institutions and members duties to clients, supply chain and employees. Furthermore, the CIOB recommend and advocate strongly around services needing to be performed to a high-quality standard and to achieve value for money for clients. They have also reinforced the importance of professionalism and duties owed to the general public to enhance the reputation of the construction industry.

The CIOB Rules and Regulations of Professional Competence and Conduct (CIOB 2019) consists of 14 rules governing what members should demonstrate, undertake and fulfill in discharging their duties with complete fidelity and probity. They also include four regulations related to use of distinguishing letters, logo, advisory service and advertising. Figure 10.8 contains some rules related to complying with their conduct for CIOB members in this regard which are predicated on the common premise of competencies, trust, respect, professionalism and honesty.

Figure 10.8 Rules relating to the CIOB codes of conduct.

10.14 Summary

For a professional institution to gain public confidence, maintaining ethical practices are very important, as they have a direct influence on quality of those services provided to clients and the public image and perception. Codes of ethics can be described as a statement of the core values of organisations and of the principles which guide the conduct and behaviour of organisations and their employees in all their business activities. Members of professional bodies are bound by these codes of ethics, sometimes referred to as ethical principles, to address the issue of non-ethical behaviour and to attempt to provide a context of governance. These institutions have strict charters, professional codes of conduct and ethics, rules and regulations relating to professional standards that individual members are required to follow and adhere to and they reserve the rights to take action against members who breach rules and regulations laid down. Accordingly, introducing codes of conduct, codes of ethics, rules and regulations by professional institutions instils a strong message and indication to members on what is expected of them and can serve as ‘checks and balances’ for individual members to try to curb unethical or immoral behaviours. They can also send a strong signal to other stakeholders that unethical practices will not be tolerated, and this could assist in reducing the undesirable practices and behaviours on a global level.

In considering the governance and regulation, professional ethics are policed by a national or international body to ensure a minimum standard of practice for organisations to strictly adhere to. Professional institutions or organisations can impose strict penalties for codes which are violated to deter unethical practices and behaviours. In this sense, however, ethical codes of conduct should not be regarded negatively as a framework for punishing breaches but positively in assisting professionals in recognising their own moral parameters. Clearly corrupt behaviour is subject to more than just policing by professional institutions and in some cases can be deemed criminal offences.

Where misconduct and unprofessional behaviours have been identified in the past, this has had negative implications on the way the construction industry has been viewed and, in some cases, this has led to public concern and government attention. To address this, there has been a concerted effort to improve confidence and trust amongst the general public in light of some cases of professional misconduct. Professional ethics, reinforced through professional standards of professional bodies and codes of practice, have played an important part in gaining this confidence and trust alongside respectability and integrity. However, these codes and standards need to be embodied in management practices and roles and responsibilities assigned to ensure compliance across ethics programmes.

Codes of conduct are sometimes anchored around the Seven Nolan Principles and embedded as core requirements for organisational financial regulations and these are selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership. Codes of ethics should reflect the practices and cultures which construction clients want to encourage for their respective organisations and project teams. The Code of Ethics Checklist devised by the Chartered Management Institute provides clear guidance for employees on what is expected of them in terms of ethical behaviors and practices. This sends a clear signal to other parties including customers and suppliers that unethical practices are not acceptable. To support their Codes of Conduct and Professional and Ethical Standards, the RICS have quite helpfully created a decision tree for proceeding or not proceeding with certain courses of action, and for decision making in these situations.

References

- Abdul Rahman, H., Karim, S., Danuri, M., Berawi, M., and Wen, Y. (2007). Does professional ethics affect construction quality?Retrieved from www.sciencedirect.com [accessed 24th November 2019]

- CIOB. (2019). Rules and Regulations of Professional Competence and Conduct. The Chartered Institute of Building. Retrieved from www.ciob.org accessed 23rd May 2020.

- CMI. (2010). Code of professional management practice . Retrieved October 12, 2010, from www.managers.org.uk/code/view-code-conduct [accessed 24th November 2019]

- CMI. (2013). Codes of Ethics Checklist. London: Chartered Management Institute.

- Fewings, P. (2009). Ethics for the Built Environment. London: Routledge.

- Haralambos, M. and Heald, R.M. (1982). Sociology: Themes and Perspective. Slough: University Tutorial Press Limited.

- Henry, C. (1995). Introduction to professional ethics. Professional Ethics and Organizational Change, 13.

- Inuwa, I.I., Usman, N.D., and Dantong, J.S.D. (2015). The effects of unethical professional practice on construction projects performance in Nigeria. African Journal of Applied Research (AJAR) 1 (1): 72–88.

- Latham, M. (1994). Constructing the Team. London: The Stationery Office.

- Lere, J.C. and Gaumnitz B.R. (2003). The Impact of Codes of Ethics on Decision Making Some Insights from Information Economics. Journal of Business Ethics 48 (4): 365–379.

- Liu, A.M.M., Fellows, R., and Nag, J. (2004). Surveyors’ perspectives on ethics in organisational culture. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 11 (6): 438–449.

- Oladinrin, T.O. and Man-Fong Ho, C. (2014). Strategies for improving codes of ethics implementation in construction organizations. Project Management Journal 45 (5): 15–26.

- Poon, J. (2003). Professional ethics for surveyors and construction project performance: What we need to know. Proceedings of The RICS Foundation Construction and Building Research Conference (COBRA) 1st September to 2ndSeptember 2003 . London. RICS Publications

- RIBA. (2005). Code of Professional Conduct. London: RIBA.

- RICS. (2000). Guidance Notes on Professional Ethics. London: RICS Professional Ethics Working Party.

- RICS. (2001). Professional Regulations and Consumer Protection Department. London: RICS House.

- RICS. (2010). Maintaining Professional and Ethical Standards. London: RICS.

- RICS. (2021). Independent review in respect of the issues raised at RICS in 2018 and 2019 following the commissioning by the RICS audit committee of a treasury management audit. RICS publications

- Stewart, S. (1995). The ethics of values and the value of ethics: Should we be studying values in Hong Kong? In: Whose Business Values, (eds. S. Stewart and G. Donleavy ), 1–18. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Press.

- Svensson, G., Wood, G., and Callaghan, M. (2009). Cross-sector organizational engagement with ethics: A comparison between private sector companies and public sector entities of Sweden. Corporate Governance 9 (3): 283–297.

- Vee, C. and Skitmore, M. (2003). Professional ethics in the construction industry. Engineering,Construction and Architectural Management 10 (2): 117–127.

- Walker, A. (2009). Project Management in Construction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.