chapter six People (In action)

So it is, said the Wise Eagle, that those who cheat succeed, as they get to the Emptiness faster than anybody else does.

Darloz

6.1 Introduction to Chapter 6

In order to verify that a sound work culture (psychodynamic) for a given upcoming project is present, the feasibility analyst tries to detect who is likely to be a top performer, that is, who is or can be a fully efficient Force of Production (FP), as opposed to a costly uncontrolled Force of Production, FPnc. Who is the Star?

There are ways to do this that I address in this chapter: we ought to examine personality from the angle of attachment theory1 and see how the brain, under stress (submitted to some form of threat), elects Hostile or Defensive2 behaviors—these behaviors can be so strong and enduring that they actually become part of the modus operandi of individuals. One refers in this case to so-called Instrumentally hostile (IP) and Defensive positions (DP). We must also look closely at egregious individuals, who are the most dangerous FP—these are people who are fully functional, but who operate based on a hidden agenda that can tarnish any aspect of the project. First, let’s look at commitment.

6.2 Commitment

My six core competencies model suggests that people commit to their tasks. As some people say: “You won’t go to jail if you collaborate!” For sure, collaboration is crucial, but there has to be a direction: that of realizing the project within the triple constraints. Otherwise, collaboration may just be a big party with no palpable results. I set Collaboration as a precedent to Commitment; cooperative team members show each other that they are committed. This tends to reinforce collaboration when the team spirit is positive and strong.

I did not measure Commitment in my various studies, but I believe it is akin to the idea of a cumulative effort as described by the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), with efforts focused in particular on subduing POVs. Efforts expand over time and they tend to reach a plateau as the project nears its deadline. Essentially, I assume that the Commitment curve emulates the Rn–Th curve, with cumulative efforts | constraints being on the y-axis and resources on the x-axis (Figure 6.1). A number of authors spanning across decades and countries have recognized that the issue of resource procurement and handling is important in project dynamics.3

As we have seen in the previous chapter, we already know the function of this curve because we know the function of the Rn–Th curve. The Commitment curve, as I define it here, seems to make sense; if efforts are put in, this implies some form of commitment. But efforts could be spent uselessly. However, if efforts lead to an increasing use of resources, then, most likely, People are committed to the Plan and to finishing the project; otherwise, resources (total resources, that is [R + Rn], or |R) would sit idle and team members would eventually put less effort in and even forget about their initial goals.4 People trade off present and future knowledge (Th), and present and future nonessential resources (Rn) as time goes on; for example, team members (Forces of Production) learn for a while, then relax while the new information sinks in, then they use newly acquired knowledge that complements past knowledge. This process goes on at a shrinking rate because a saturation point5 is eventually achieved, either because of fatigue or because the team members (FP) have learned everything there was to know in order to perform their tasks; say, to operate a particular, recently installed piece of first-aid machinery6 such as a defibrillator. These team members (for instance, being trained in first-aid emergencies) will have to take some time off from learning and practice a bit, before learning new things about the subject and practicing again.

Squirrels in a city park can serve as an example (not in first-aid care!). They eat nuts now (Rpresent), yet they also hide some nuts away in anticipation of future consumption.7 While eating at the present time (Tnow), they cannot dig the ground and hide nuts for future consumption (Tfuture). While they dig, they cannot eat during the present time: present- and future-oriented behaviors are mutually exclusive. In fact, these behaviors compete with each other. This competition is based on a perceived threat (apprehension) and POVs: eventually, the squirrel will be hungry and will need to feed, perhaps despite the presence of predators (the squirrel will then trade off between the risks—the predators—and its vulnerabilities—hunger). Similarly, the team members (Forces of Production) need to acquire new skills because, eventually, they can be replaced by younger, more alert, and technologically advanced employees, or else by robots. External threats such as competition from the outside and internal POVs work together to force direct and indirect resources (|R and |T) to be optimally utilized.8 This dynamic transpires in our six core competencies model: Apprehension, which invariably exists in correlation with POVs, impacts the psychological core of Trust–Fairness–Collaboration, which then, over time, supports commitment, which amounts to efforts being made in using all of the resources efficiently in order to complete the project.9

I hypothesize that saturation points for present and future uses of resources are achieved at the dynamic Point of Equilibrium. Indeed, because resources (direct and indirect) have a life span, that is, as saturation points only last a certain amount of time, the Point of Equilibrium (of homeostasis) can only be dynamic.

This perspective allows me to qualify Commitment as a series of efforts made using a certain number of resources, whether direct (R + Rn = |R) or indirect (T + Th = |T), that are spread along a time line (in reality, that are submitted to the utility drawback) that outlines a competition between present and future use, and that leads to at least one saturation point.

The following is the equation for Commitment, as I assume it to be, with |R and |T:

or

or

Recall that I plotted the R−T and the Rn−Th curves on the same graph to find the point of autonomy and to discuss the dynamic Point of Equilibrium. I assume that I can do the same here: the Commitment curve goes up and the Fairness curve goes down.10 As time goes on, People express more grievances because they discover unheard of POVs that play against their own welfare and hence tend to want better working conditions; at the same time, they must perform and put in more effort (as they operate in a closed dynamic system that is bound by the utility drawback or triple constraints). The point where they feel that they are treated reasonably well while not overextending themselves forms a psychological state conducive to productivity and repellent to counterproductivity. This point is, of course, the dynamic POE (multidimensional Figure 6.2).

It is worth noting that in recent studies (at least, those I have accessed) in the field of project management, the constructs of Control, Trust, Collaboration, and Commitment, all appear as behavioral competencies in IT projects; yet, Transparency and Fairness are ignored.11 Numerous studies on competencies in project management fall short of identifying Transparency and/or Fairness (or the sense of a win-win situation) as being important factors, when in fact it is hard to imagine anyone wanting to commit to a series of tasks and perform at a high level while feeling something is hidden from them or that they are being or will be treated unfairly.

The feasibility analyst may pose three questions when looking at a project proposal:

Are adequate managerial skills in place?

Do all of the stakeholders trust the project and each other?

Are all of the necessary total resources available (|R and |T)?

I assume that these are sine qua non conditions to the feasibility of a project within the triple constraints (Figure 6.3).

Overall, I have hypothesized that Commitment and Fairness share some common grounds: there is an interplay between them that allows me to plot their curves on the same graph.

6.3 Identifying the stars (top performers)

Functional groups are divided differently depending on the author. The PMBOK classifies what I call the “controlled Forces of Production’ (FPc) according to the stage of the transformation process: (1) start (vision), (2) planning, (3) execution (mobilization), (4) monitoring and control (deployment), and (5) closing (completion/evaluation).

Finding the right employees (the “Fits”), and especially the top performers (the “Stars,” those who display the ideal DS and CS curves), for the completion of a project is key to meeting its deadline, budget, and norms of quality. A project may incorporate great employees, but it may also be subject to bad apples or Unfits. Additionally, a project is naturally prone to some forms of defects (POVs). As pointed out by some authors:

(…) based on the interviews with project management professionals, it is clear that project-based work does produce a number of unintended pathogens that can significantly affect both the way in which project management professionals do their work as well as they manner in which they interact with critical stakeholders.12

Not only are projects sensitive to constant changes, but the current world itself sees dramatic turmoil (environmental, legal, and political) that may represent clear and present danger (risk), at a rate probably never seen before. This is even truer in the context of international projects, where stakes are spread across cultures, distances, and time differences.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has developed a “federated approach” that states that effectiveness is (structurally) formed of people’s skills and behaviors; this includes abilities (which I have captured in the construct of Trust), alliances (which obviously are related to the construct of Collaboration); assignments (which are included in my construct of Work or T); and attitude (which I include in my construct of Consideration). All of this ultimately serves to differentiate between functional and dysfunctional People.

Increasingly, projects resort to cross-functional work performed in multiple locations based on a diversity of teams.13 The temporariness and heterogeneity of the workforce renders the working environment more volatile and more vulnerable than before. Inefficient employees (FPnc) may not be promptly detected. Opportunities for conflicts may arise faster because unknown factors surface; this happens within a pressured framework that commands specific deliverables, given time constraints, and a predetermined budget. Many risks hinder project developments. In addition, projects must integrate various areas of knowledge and expertise (Th) in unique ways. This is true for projects of all disciplines (including software projects) from decades of project ventures.14

As such, a project environment is subject to high volatility. One can say that the key characteristic of contemporary projects is, indeed, volatility: a characteristic that did not exist to such an extent in the past and that is likely to rise in intensity in the future. More and more, innovations invade markets, projects are developed internationally, the workforce is multicultural and multidisciplinary, and events succeed each other at high speed given such communication tools as the Internet.

The volatile reality of contemporary project environments suggests a potential for “shocks of personalities” to occur.15 These clashes lead to the rise of insecurities. Indeed, employees sometimes feel threatened by their coworkers, their employers, or their environment. Insecure employees beget more volatility, and as the sense of threat worsens (the threat toward one’s job or safety and security, fear of negative outcomes as a project develops, etc.), employees lose motivation, make more errors,16 and resort to counterproductive behaviors.

A review of actual projects across various countries reveals that both personality (profile of shareholders) and what is called an “attitude toward risks’, are assumed to play a role in project outcomes.17

Indeed, it has been found that “the underlying cause of most disputes was the reaction to the (…) personalities of the key players (…)”18 However, it may not be so much the personality types than the way individuals respond to threats that matter in a project environment. It thus appears important to examine what threats are all about and how individuals process them.

Some authors recognize the fact that “(…) there are at least two quite separate types of threat. On the one hand, there is a definite, localizable, actual threat (…); and, on the other, there is indefinite, diffuse, potential threat, (…).”19 However, the authors also note that “the threat must be only mild if approach is to be a viable option.”20 Transposing this in the reality of a project environment, it may be that an employee who perceives his employer or his environment as a threat will tend to avoid it or else react in a counterproductive manner.

Inasmuch as there is high volatility in contemporary projects, certain pillars of stability provide a base for the development of the project. Managerial tools and techniques such as those promoted by the Project Management Institute (PMI)21 are used internationally. Given that the expression of some emotions (e.g., hostility) is similar among different cultures,22 some managerial techniques that assist with the decoding of verbal and nonverbal cues may deal with them with a certain level of success. These factors of stability help to provide a productive environment, but do not necessarily overcome difficulties arising from employees showing flimsy project capability. Additionally, they take place during the transformation stage, not before. Our objective is to detect and minimize the POVs related to People’s inabilities before the project begins, at the feasibility analysis phase.

The term project capability can be associated with the capacity to adopt “the appropriate knowledge, experience and skills necessary to perform prebid, bid, project and postproject activities.”23 It is to a project what a Dominant Strategy (DS) is to the manager. Project capability is imperiled by exceedingly volatile environments that present previously unseen challenges, hence the importance of the proper screening of employees prior to commencing the project or even during the realization of long-term projects. I assume that there are employees with high and others with medium and low project capabilities and consider that it is important to identify them ahead of time in order to secure proper project evolution and ultimately completion within time and budget constraints.

The project management literature addresses the personality of leaders—especially with respect to leadership style—in an attempt to somewhat explain project capability. On the other hand, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV24 (the most notorious authority in terms of personality assessment) states that personalities contain structural and functional domains, along four levels,25 as follows:

The behavioral level, marked by expressive acts (e.g., impulsivity) and interpersonal conduct (e.g., exploitative).

The phenomenological level, which includes cognitive style (e.g., pessimistic), object representation (e.g., concealed), and self-image (e.g., discontented).

The intrapsychic level, with its morphologic organizations (e.g., divergent) and regulatory mechanisms (e.g., dissociation).

The biophysical level, referring to mood and temperament (e.g., hostility).

I choose to concentrate on a limited version of this appraisal of personality, with the key components put in parentheses—I am searching for top performers, that is, for the Forces of Production (FP) that can most probably swoop down on POVs and lead the project toward its forecasted completion.

In the context of management, it has been shown that control (being assertive, taking charge) and competitiveness (a dislike of losing and willingness to win) are two personality traits that predict whether managers will achieve higher rankings in the organization’s hierarchy; this research covered a seven-year stretch.26 Some authors found that intelligence was to be regarded as “the most important personality attribute (…), followed by physical condition, maturity, sensitivity, emotional stability (…).”27 I argue that intelligence is not, however, a personality attribute.

For the most part, the literature focuses on the technical skills of project managers,28 not on the interpersonal skills of stakeholders, including employees. Technical skills address one of the structural components of Trust (Abilities) but are far from encompassing other psychological variables that form Trust—Benevolence, Affinity and Integrity—or Collaboration—the capacity to be flexible, to exchange information, to solve problems jointly and to be tactful and supportive when interacting with others (so-called consideration).

Various tools are promoted for capturing managers’ personalities, and countless studies have reported results based on the “Myers–Briggs personality test” (MBTI). Many authors29 have resorted in their research to the “Big Five” personality factor theory—agreeableness (friendly/considerate), conscientiousness (efficient/organized), extraversion, openness to experience, and neuroticism (negative emotions)30—and to conflict resolution styles such as accommodating, avoiding, collaborating, and competing31 as well as compromising and enforcing. Various studies report correlations and predictions based upon the Big Five. Yet, it has been noted that “although this model is generally accepted, it has not always been agreed upon that five major factors explain personality, neither has the definition of each factor received consensus.”32

Research has supported the utility of personality assessment tests, but only to a limited degree, alongside other forms of assessment.33 Such tests are recognized as an aid to select employees34; yet, they do not hold strong predictive power.

6.3.1 A personality theory

Coping mechanisms have been acknowledged by many scholars35 by way of an established four-personality model36 (avoiding, anxious, hostile, and stable) under the Attachment theory. Escaping/avoiding personalities tend to run away from the source of threats. Anxious personalities establish shaky relationships with their colleagues. Hostile personalities resort to aggression. Finally, secure (stable) personalities have enduring traits that are most conducive to performance. Several studies (some spanning several decades) have demonstrated that secure individuals tend to be endearing. They stay married longer—in other words, attachment is a good predictor of the length of a relationship.37 It has been found that couples that display communication, intimacy, secure emotional commitment, and trust are more accommodating and caring than others.

Most obviously, a project leader would want to be surrounded by stable personalities and free of pugnacious ones, hence the importance of identifying them. The coping strategies underlying the attachment model have been at the heart of other research. For example, some authors have emphasized the following characteristics: confrontational coping (hostility); escaping, avoiding, and distancing (avoidance); social support–seeking (possibly anxiousness); and finally self-controlling, being responsible, effortful problem-solving, and positive reappraising (stability).38 PMBOK 5 (p. 53) refers to “core personality characteristics.”

The four personalities described in the Attachment theory (anxious, avoidant, hostile, stable) have been heavily documented. Anxious people, for example, make more errors and repeat their errors over time, thus showing poor learning from past experience.39 In particular, research shows that contrasting personalities react differently to trust building and trust violation: more secure individuals tend to favor intimacy in the first case and to talk with a significant other in the second scenario. Avoidant and anxious people long for security in the first case and resort to denial (avoidance) or rumination (anxiousness) in case of trust betrayal.40 Anxious people, in their need to find security, tend to over-trust, that is, to blindly fall into other people’s arms without regard for their own vulnerability.

My own research shows that stable individuals form ideal candidates while unstable individuals see a 20% reduction in their capacity to trust and collaborate with others, versus stable individuals. Stable individuals are likely to deal with conflicts in a fruitful way, to display efficient tolerance to risk, to encourage a means-end approach, and to exercise smarter forms of control. In this book, I do not view being “stable” as a personality trait; rather, I believe it is a condition resulting from well-organized personality traits.

People rarely adopt one single personality trait at once, but experience bouts of these various traits (anxiety, avoidance, etc.) so that an overall balance is established between Hostile and Defensive positions, much in line with a prediction deriving from Lotka–Volterra equations.41 In other words, people tend to be stable. Indeed, stable people make sound decisions and establish durable relationships.

Thus, different strategies aimed at building trust are necessary, with each speaking directly to the particular team member (the one exhibiting offensive42 or defensive behaviors, or else stability43).

The well-known Big Five nomenclature does not allow for differentiating between so-called stable and ill-disposed personalities and hence cannot be used as a valid tool to achieve this, even though it refers somewhat to personality styles as given by the Attachment theory: agreeableness (stability), conscientiousness, extraversion, openness to experience (the reverse of avoidance), and neuroticism (anxiousness). Furthermore, to the best of my knowledge, there is no neurobiological evidence supporting the Big Five theory or other similar theories. However, I can fit some elements of the Attachment theory into the way the brain actually works.

6.4 Hostile and defensive behaviors

I simplify the aforementioned theories by proposing a dual coping mechanism, that of instrumental hostility and defensive hostility. The latter would include anxious (the “maybe”), avoidant (the “I gotta go”), and resistant (the “no”) individuals. I bet that many project managers who read this book recognize these patterns.

A note here to warn the reader to differentiate between Dominant and Contingency or Short strategies, and Instrumentally hostile and Defensive behaviors nested deep in the brain (the hypothalamus). As explained in Chapter 1,44 a Dominant strategy and a Contingency strategy refer to a managerial stance which we compared with strategies wielded by chess players: both positions have value. Hostile and Defensive behaviors refer to behaviors that occur as the result of experiencing Apprehension (a perceived threat, or a vulnerability, e.g., being hungry would lead a tiger to become a ferocious creature). The Dominant strategy, DS, is far from being malignant: it is a strategy adopted to complete the project. Individuals who master Dominant and Contingency strategies (as opposed to Short strategies) have also mastered the art of controlling hostile and defensive behaviors to serve their objectives. On the other hand, defiant behaviors disrupt projects.45 Note that defensive hostile behaviors are temporary in nature.

Hostile and Defensive actions and reactions are coping mechanisms because they are awakened in situations of apprehension (perceived threat). Once coping mechanisms have an enduring presence, I characterize them as (instrumentally) Hostile position (IP) and Defensive position (DP). When the enduring presence appears regularly, at least within the realm of a short- or medium-term project, I qualify the position as profile. When it is part of the personality of the individual (which is divulged most often during long-term projects), I then use the terms (instrumentally) hostile and defensive personalities, which, as mentioned, come in three personality types: anxious (A-X)—the “maybe” people; avoiding (A-V)—the “I gotta go” people; and resistant-defensive (A-R)—the “no” people. To review, we have

Short-term coping mechanisms (reflex-based): (instrumentally) Hostile and Defensive behavioral responses.

Midterm coping mechanisms (including both emotional and cognitive efforts): (instrumentally) Hostile positions, IP, and Defensive positions, DP.

Longer-term coping mechanisms (with their loads of emotional, cognitive, and conative characteristics): (instrumentally) Hostile and Defensive profiles.

Enduring mechanisms (with their set emotional, cognitive, and conative patterns that define individuals): (instrumentally) Hostile and Defensive personalities.

As mentioned, so-called stable personalities are not personality per se in my model; rather, stability is a trait or state that results from people managing all four basic coping mechanisms (instrumental aggression, anxiety, A-X, avoidance, A-V, and resistant-defensiveness, A-R) in an effective way, given the circumstances. It is actually risky to pretend that we can identify personalities without doing long-term, longitudinal research, which we have not done. My results thus focus on positions and profiles rather than on personalities, hence the terms “Instrumentally hostile position”, IP and “Defensive position”, DP.

Also, the reader, who may not be familiarized with the functioning or the anatomy of the brain, may consult Appendix 6.1 and simply view the brain as a mechanism. In Appendix 6.1, I have endeavored to portray the brain much like a machine with its separate parts and underlying constructs (e.g., Trust) in order to ease the understanding. The brain is a convoluted system that is controlled by some set pathways and behaviors, by a clock (in the hypothalamus46 and in genes), and by homeostasis standards (stored in the hypothalamus47).

The key point of this discussion is that a project should be free of spiteful behaviors; they represent significant POVs because hostility elicits hostility (and retaliation), causes instability, and damages trust.

There is neurobiological evidence supporting the four types of coping behaviors that are generated when facing external threats or internal vulnerabilities (in both animals and humans), which, when properly balanced, are assumed to form so-called stable personalities. Consequently, and as mentioned, stable personalities are seen not as personalities per se, but as the result of an individual adequately balancing his reactions or coping mechanisms when experiencing apprehensions.

The hypothalamus is, indeed, the brain structure that governs the four coping responses (also called “adaptive responses”;48 again, see Appendix 6.1 to gather more details on the brain and the hypothalamus). It contains encoded (or “encapsuled”49) patterns that date back to our human phylogenetic ancestors.50 Obviously, they impede on the development of trust, because by definition, they manifest themselves in the presence of perceived or real threats (that cause apprehensions). In a purely raw animal sense, the four patterns can be classified as follows51:

Instrumental aggression52 is commonly called “hostile” (IP). In nature, one calls it predatory behavior: actions are planned and calculated to catch prey by surprise,53 serving the predator’s interest and causing that prey harm or death. One talks of an abrasive personality, or, in psychiatric terms and when pushed to the extreme, of (functional) psychopaths. From a project management perspective, this refers to hostile, feisty individuals.

Freezing, fleeing54, and defensive rage.55 These actually translate into the three following defensive positions: anxious (A-X)—the “maybe” people, avoiding (A-V)—the “I gotta go” people, and resistant-defensive (A-R)—the “no” people.

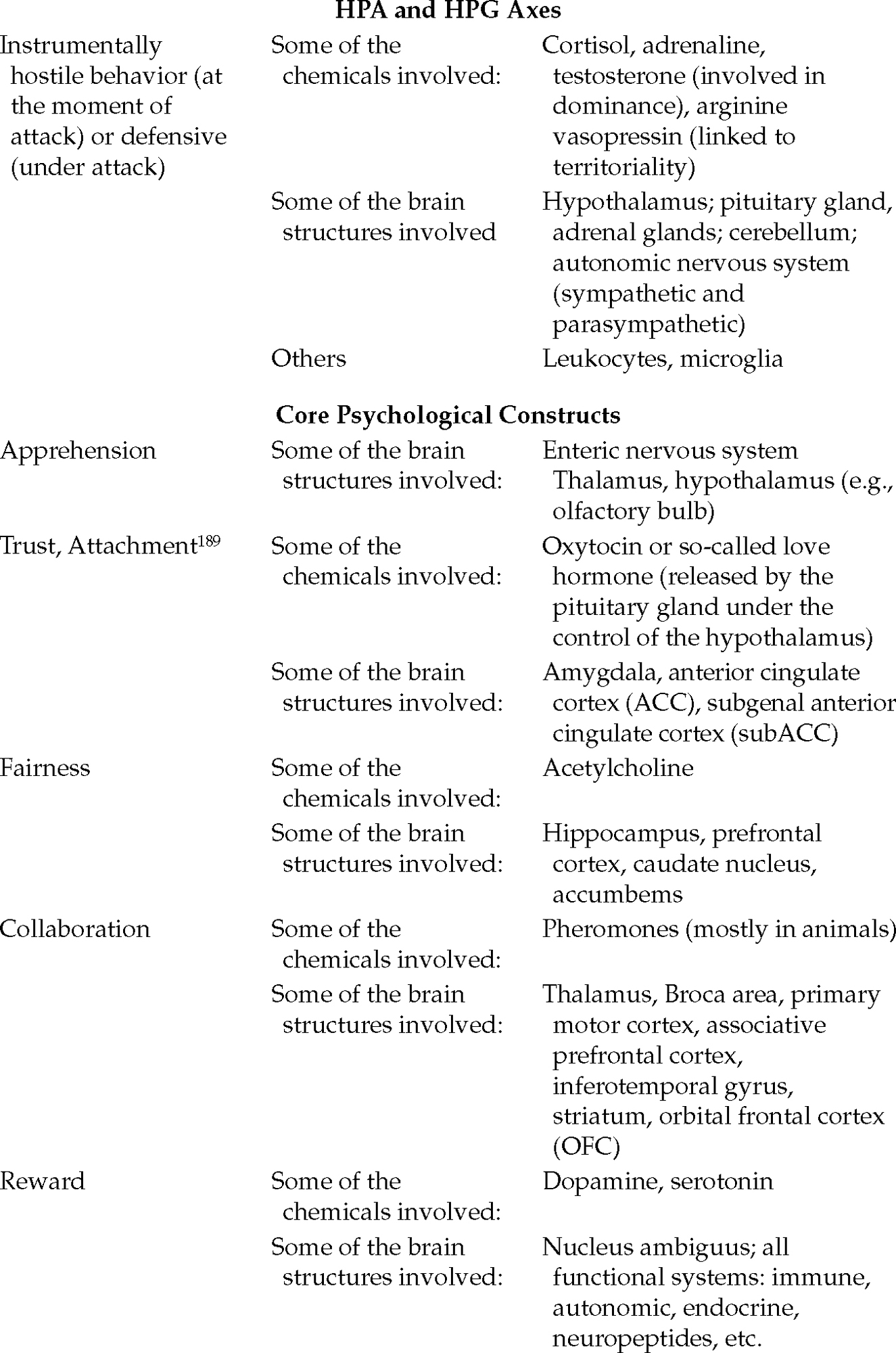

The four behavioral positions model is based on ethological and neurobiological evidence. In short, four responses to threats are recognized, one being purely offensive—instrumental aggression (or IP in the terminology used in this book) and the other three being defensive (freeze, flight, or fight—also referred to as “defensive aggression”). This is represented in Table 6.1, where A-X, A-V, and A-R combine to form a DP in contrast with an IP.

Anxiety (A-X), flight (A-V), and resistant-defensive fight (A-R) are responses to threats that are found in all animals:56 “Fight, flight, and freezing are at the lowest level and result from a contacting or proximate danger, circumstances in which there is little time for analysis of the situation or freedom of action.”57

| High (T/CRT) (steroids) | Low T/CRT) (steroids) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Low impulsivity (slow) | IP: instrumentally hostile | Freeze/Anxious (A-X: anxious) | High (5-HT/OXT) (hormones) |

High impulsivity (fast) | Resistant-defensive fight (attack to resist: A-R) | Flight (escape) (A-V: avoiding) | Low (5-HT/OXT) (hormones) |

Defensive coping mechanisms, transferred into a human context, have been found to be counterproductive in many projects, across decades and across countries (Table 6.2).58

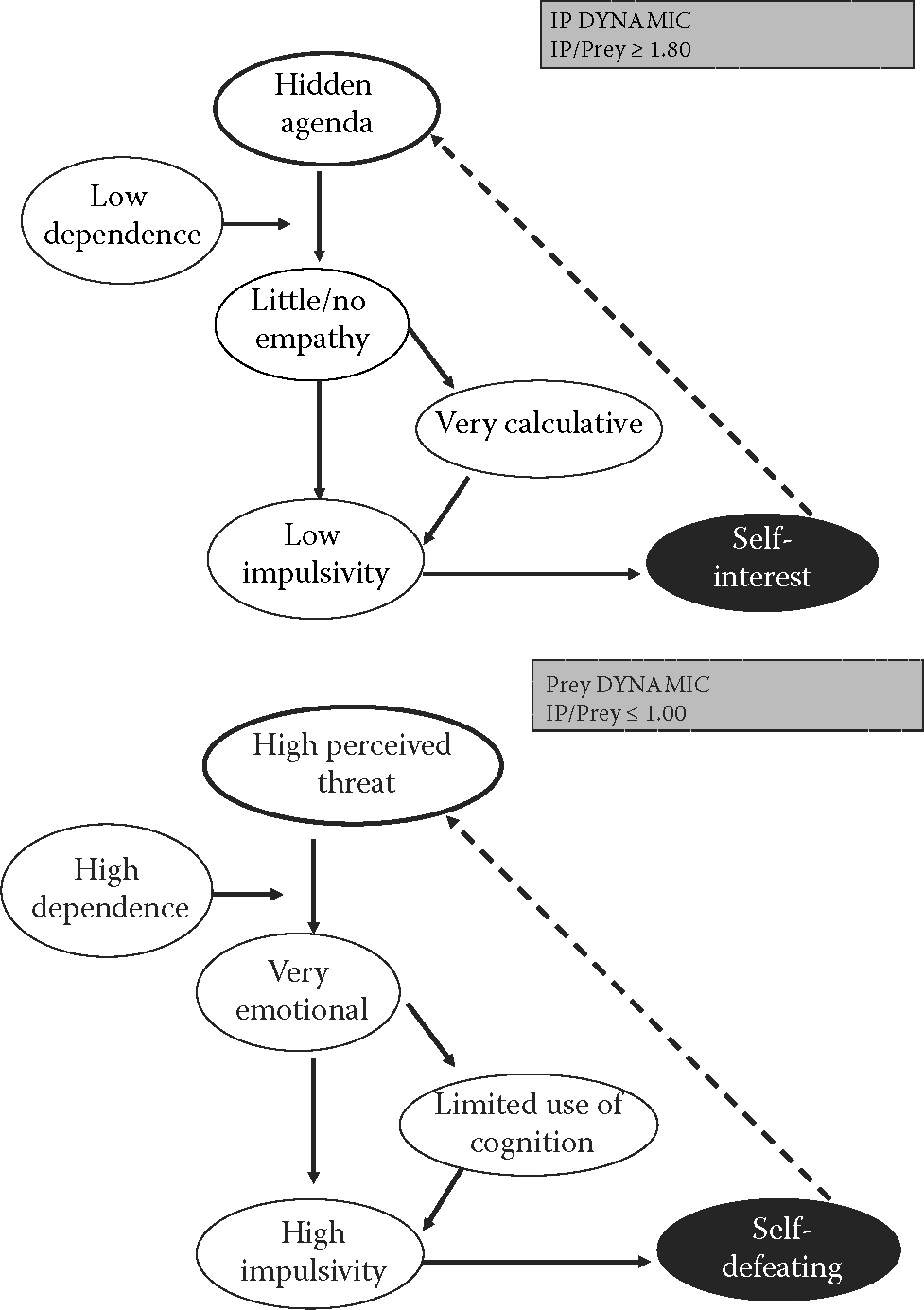

Both instrumental and defensive aggressions have been extensively studied, especially in cats, who, like humans, are also mammals. Recent research provides the evidence59 shown in Figure 6.4.

In the model shown in Figure 6.4, an emotion leads to a response. The response is composed of two mutually exclusive reactions (hence the inhibition-activation mechanism): either offensive (IP—predatory) or else defensive (prey). The periaqueductal gray region (PAG) of the brain serves as an absolute mediator; this means that should the defensive reactions be opted out, the road to the alternative response—offensive reactions—is fully open. To use a mnemonic trick, all there is to remember is that stable people have a talent for balancing their hungry tiger side and their lonely sheep side, with the sheep freezing, fleeing, or resisting depending on which option is readily available in the face of danger. As an exercise, the reader can mentally run through his average day and check when they adopted a hungry tiger behavior (“I planned my used car purchase well in advance so that the salesman didn’t have a chance to argue with me today”) or else a lonely sheep behavior (“Today, I got ripped off by an unscrupulous used car salesman who sold me a lemon”)—most readers will be baffled at the result!

In humans, it remains unclear whether hostile and defensive behaviors are completely exclusive as is the case with cats. In other words, people would be able to stay in a defensive posture while also planning for instrumental attacks in the future. This would be the case of, for example, an employee sparring with his/her colleagues whom they perceive to be a threat, thus being constantly on the defensive, while planning to get them in trouble by way of various means (e.g., hiding some documents). However, the reality is that the individual is just switching from one coping strategy to the next over time rather than opting for them both simultaneously. In fact, when I plot some of my data and contrast the constructs of a Hostile position against a Defensive position, I obtain an R2 of 0.092, which is insignificant, signaling that the two behaviors are mutually exclusive. When I plot natural log functions of the Hostile and Defensive positions, I do obtain a near ascending linear curve as opposed to an elbow curve that would tell the story of mutually exclusive phenomena (see Table 6.1).

Indeed, I can postulate that Instrumentally hostile positions (IP) and Defensive positions (DP) are of two very different natures: they are mutually exclusive (surely in cats; most probably as well as in humans60). I opine that instrumental hostility is simply a delayed response to a defensive condition (we will see in Chapter 7 how I put this mathematically). Indeed, instrumental hostility implies low impulsivity. Some authors offer similar explanations as to how the defensive system works.61 Directed escape is controlled by the medial hypothalamus and undirected escape by the periaqueductal gray, while discriminatory avoidance of danger is the function of the anterior cingulate cortex62 and avoidance by the amygdala. The defense system is viewed as a hierarchy of coping mechanisms that can, in project management terms, lead to resistance. First, an employee says “maybe,” then they say “I gotta go,” and finally they settle for a blunt “no.”

Many brain areas are indeed solicited by hostile and defensive dynamics. Again, contrary to other personality theories, the four-encoded behavior model based on Attachment theory and various other scholarly works63 rests on sound neurobiological foundations.

Indeed, besides from the hypothalamus, the brain structures that participate in defensive responses as well as in instrumental and defensive aggression have been identified. As an example, the amygdala (in the brain) plays a fundamental role in emotions, including in “anticipated frustration.”64,65 This is in line with findings by various authors,66 who report that the amygdala plays a key role in the detection and avoidance of danger (perceived threat)67 and in socialization.

Along these lines, it has been recognized that defensive mechanisms are prompted according to two conditions: the proximity of the threat and the possibility to escape.68 According to this model, the flight response entails that the flight option is available and is more pertinent as the prey is farther away from the predator; failing that, the prey may resort to a defensive threat (resistance in the first stage) and then a defensive attack (resistance in a second stage). On the other hand, and still according to this model, the freezing response is assumed to be an available means only if flight is not an option. Again, the more intense the threat (the closer the predator is), the more the prey will resort, as an ultimate option, to a defensive threat/attack. Tests performed with cats submitted to threatening stimuli show this pattern of reactions: Cats momentarily freeze if the threat is not deemed high. If so, the cats will tend to escape if possible. If not, as the predator gets closer, they’ll make defensive threats and as the predator gets within reach, they’ll attack (defensively) the best way that they can, with the option of escaping as soon as it’s feasible. If, on the other hand, the threat seems high and the predator is distant, cats will not hesitate and run for their lives.

Here, I am telling the story of hostility and resistance so often found in a work project environment, especially when the team is not well glued together.

Defensive behaviors in the context of project management do not represent a substantial POV to the evolution of the project as they are expressed by reactive persons who can generally be controlled through adequate managerial tools such as task design and reward. The most concerning POV for a project comes from people who intentionally plan to disrupt it. This is referred to as “Instrumentally hostile individuals” (IP) or “hungry tigers”, the extremes of which are so-called functional psychopaths. Individuals adopting hostile aggression (IP) plan to stop the project’s development, either by way of, say, the creation of conflicts with stakeholders, information withholding, sabotage, or voluntary delays. This leads to apprehension on the part of other team members: as previously discussed, in the context of project management, apprehension refers to the perception one has that of the vis-à-vis has negative intentions and/or hidden destructive agendas directed against oneself. It is deeply rooted in the brain and is at the core of social behaviors. It affects such feelings as trust and may inhibit such behaviors as collaboration.69 Hence, viperous behaviors have the potential to poison a working atmosphere.

A factorial analysis has been offered that contrasts defensive, instrumental aggression, and stability from a personality point of view.70 According to this model, well-adjusted individuals belong to a group that is separate from a group consisting of individuals who manifest compulsive, paranoid, passive-aggressive, and schizoid behaviors and from another group of individuals generally described as cyclothymic, hysterical, or sociopathic.

IP-associated types of individuals differ from passive (reactive) individuals, they have been described in these terms: “Given an appropriate incentive, they simply exploit whatever resources are available to gain advantage (…)”71 Along these lines, it has also been said of them that they are “Pursuing one’s concerns at the expense of the other party.”72 Hostile personalities are indeed a POV.

The reader can imagine what kind of dynamic is likely to take place within a project should the workforce be plagued with hostile individuals. A concrete example has been provided: “As a result, they developed a closer relationship with the architects and viewed the contractor’s motivations suspiciously, believing they possessed a hidden agenda.”73

In short, defensive personalities are mostly reactive. A proper environment will guarantee that they perform according to plan. Hostile individuals, however, voluntarily try to ruin the project on many fronts, most commonly in viscous ways.

Given that 70% of a project manager’s time is spent communicating with people, and given that we have partly defined collaboration by the capacity to exchange information, hostile individuals—with their hidden agendas—are likely to have a strong negative impact on a project’s evolution and to awaken their coworkers’ defensive mechanisms. Hostile individuals strive on manipulating interpersonal conflicts (sometimes defined as “the perception of interpersonal incompatibility which includes annoyance and animosity among individuals”74 as well as “tension, irritation and hostility among team members”).75

While conflicts associated with tasks are sometimes found to be beneficial—as recognized by many authors76—they are not always productive. In fact, dysfunctional conflicts obliterate trust.

I proceeded to retrieve a database dating back to 2008 with n = 300 in which all four constructs of relevance (Instrumentally hostile position, IP, Defensive position, DP, Collaboration, and Dependence) were measured.77 I performed a number of cluster analyses testing for the most-eloquent scenario. The best output is shown in Table 6.3.

| Class | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 |

Hostile (IP)/Defensive positions (DP): (k’) | 1.55 | 1.30 |

Collaboration/Dependence | 5.67 | 1.22 |

Number of observations | 5 | 295 |

Only a small percentage of individuals (5/300 = 2%) fall into the potentially hostile category (high [Hostile position/Defensive position ratio] with a relatively high [Collaboration/Dependence] ratio), which again is expected, given the voluntary setting (respondents could leave the project if they wanted to). The results show that our measuring system that employs two ratios (Instrumentally hostile position/Defensive position and Collaboration/Dependence) seems to make sense and could be utilized to assess hostility, subject to further research.

The constant k is found with the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio for group 2; k is established at 1.3 for the large majority of participants. It can be inferred that this sample population of n = 300 is representative of the average population.

Interestingly, the corresponding Collaboration/Dependence ratio is similar, at 1.22, to k. Overall, a Hostile position/Defensive position ratio (a proxy for Self-confidence) given a particular Collaboration/Dependence ratio seems to relate to individuals characterized as stable under the Attachment theory. This remains to be probed further.

6.5 Hungry tigers and lonely sheep under stress

When conditions that have favored hostile or defensive (freeze, fight, and flight) actions and reactions persist over time, what amounted to simple reflexes become more enduring traits, at least for as long as those conditions remain. Slowly but surely, individuals adopt their actions and reactions as a means of coping and eventually as a means of being. An individual adopting a DP, for example, is to a certain extent making the choice not to be instrumentally hostile. For those who have seen the movie Silence of the Lambs, this is easy to comprehend: Jody Foster is, for a while, the lonely sheep. While she plays the lonely sheep, she is not out actively chasing the villain. She becomes the hungry tiger toward the end of the movie, when she catches the (dysfunctional) psychopath.

Both perceived and actual threats beget stress in the eye of the receiver. As is well documented, stress may be dysfunctional. High stress levels are known to increase the occurrences of depression and cancer for both animals and humans.78 In laboratory experiments, three-quarters of mice submitted to electric shocks with no possibility of escape eventually suffered from tumors. On the other hand, a quarter of the mice that could escape did not develop such health impairments.79

In the context of projects, stressful events oblige team members to stand hypervigilant, a posture that leads to fatigue, and thus, to lower productivity. Team members (just like animals) adopt two contrasting positions under stressful conditions: one of instrumental hostility and the other defensive (possibly including resistance). Indeed, findings have been reported whereby small changes in posture breed predator (IP) or defensive mental positions, alongside neuroendocrinal changes.80 This is important to know for the project manager: Who hasn’t faced resistance from team members when trying to implement a change in a project?

When I plot the ratio [Hostile position/Defensive position] as a proxy for risks against [100-Trust81], I obtain somewhat of a rectangular hyperbola. Recall that most of my data has been obtained in environments where stress was moderate; I predict that under more stressful conditions, the ratio Hostile position/Defensive position would grow faster than the function [100-Trust] so that the curve would eventually adopt the shape of a rectangular hyperbola.82 We would have Figure 6.5.

This requires further study, but again, finding teams that are willing to be tested while under high levels of stress is quite difficult.83 However, the tests I performed and that are discussed in Chapter 7, point to the fact that under high stress conditions, the element of vulnerability (herewith somewhat expressed by [100-Trust]) is temporarily put aside in favor of an IP response, which tends to shift the U(DS) into the shape of a rectangular hyperbola.

6.5.1 A study

I conducted a study to verify whether I could differentiate between the two positions based on k’ values. I included the construct of Dependence to examine its role in our six core competencies model (Dependence not being a core competency, however).

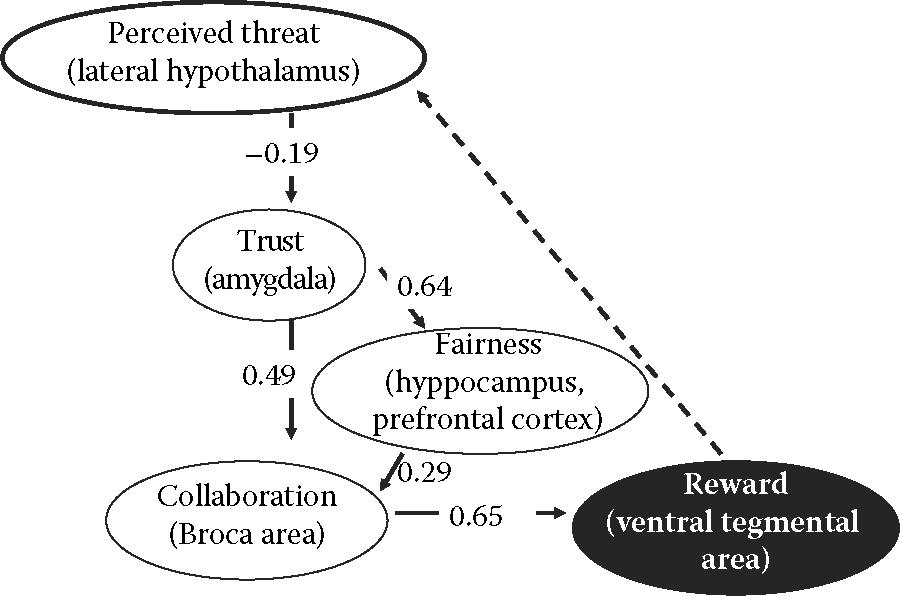

Figure 6.6 exemplifies how I went about adapting the six core competencies model to fit the two positions.

As can be seen from Figure 6.6, the model differs substantially between the two positions—Hostile (instrumentally hostile) and Defensive. Note that I replaced Commitment with Reward because a reward can be measured in the brain: dopamine levels, for example, are an expression of some sense of satisfaction resulting from a reward. Yet, because I tested before the project was completed, I assumed that participants would have left the project if they could not reap any benefit from it. Therefore, that reward was in the end replaced by intention to stay in the project.84

6.5.2 Results

I ran a structural equation modeling (SEM) test on a database of 1324 participants issued from 33 different group projects that I collected over the years, using Amos software (part of my analysis consisted of separating them into two groups—controlled, CG, and uncontrolled, UTG.

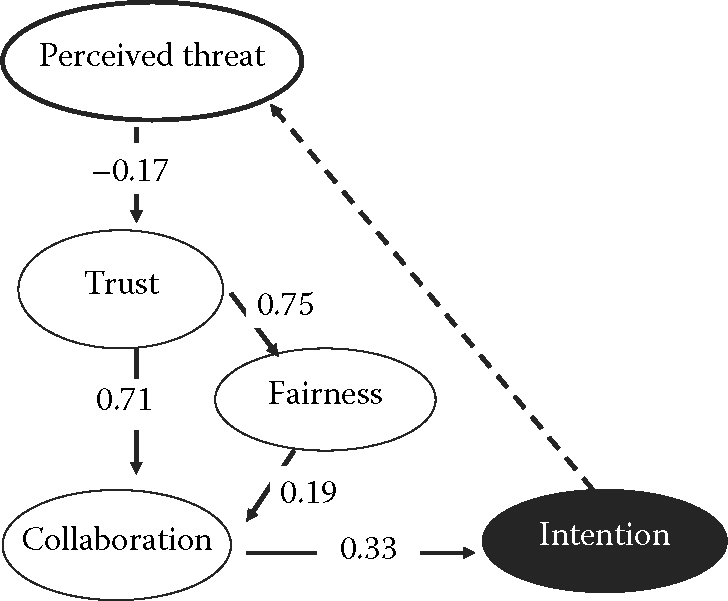

Results, for the entire group, irrespective of the k’ value, are shown in Figure 6.7.

The model presents a good fit.

6.5.2.1 Single regression analysis: Trust => Collaboration

Irrespective of the SEM, I verified that the link between Trust and Collaboration was as per expectation, for the entire group. The group displays a normal distribution: in other words, it behaves normally. It shows a strong correlation between Trust and Collaboration.

The R2 for [Trust => Collaboration] is 0.734 for the CG and 0.917 for the UTG;85,86 both show well-distributed data forming an elliptical shape around the mean (what I call the “football” shape).

6.5.2.2 Factorial analysis

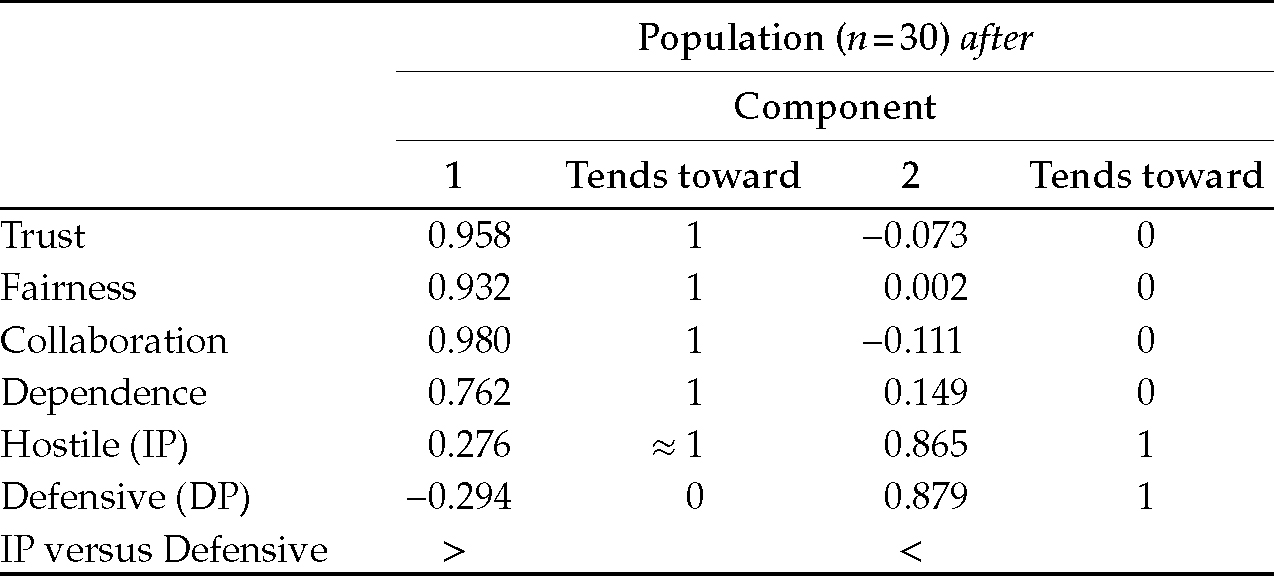

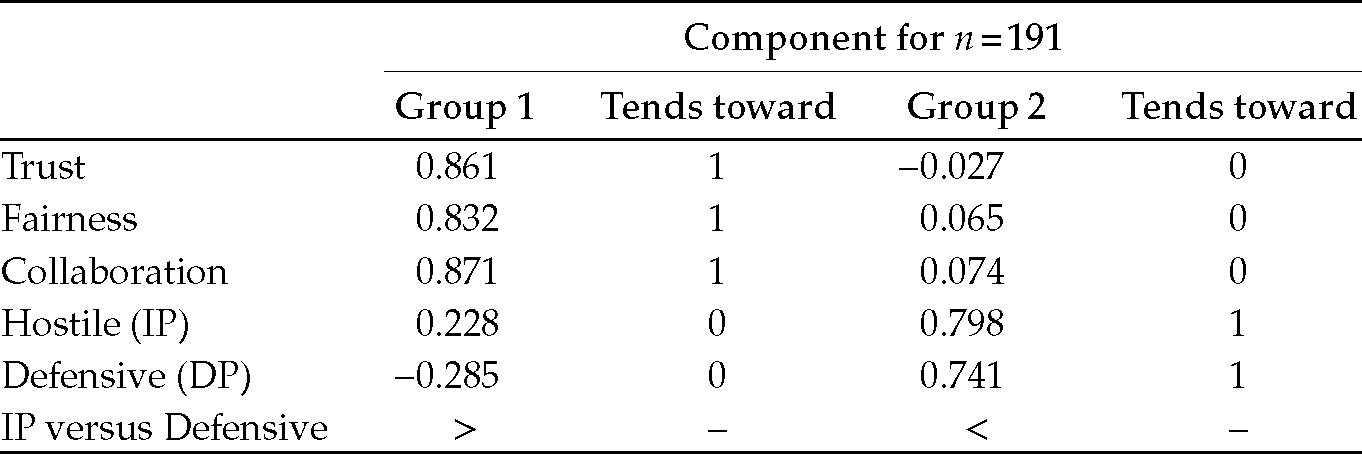

I also wanted to check whether the law of Apprehension—which is at the heart of our model—applied as expected.87 The factorial analysis results are listed as shown in Table 6.4.

In short, the listed results are in line with all of the other groups I have studied over the years. This means that this sample can probably be generalized so that I could pretend it is a fair representation of the population at large (within the limits associated with my research), at least on these important characteristics.

6.5.2.3 Evidence of the two positions

Various results with respect to two ranges of k’ values were obtained. I proceeded this way because my research indicated that a k’ value equal to or higher than 1.80 is indicative of a hostile profile and that a value equal to or lower than 1.0 signifies a defensive profile (Figure 6.8).

Table 6.5 compares the sets of values (indicators linking the constructs).

Some differences are noticeable in the relationship between Apprehension and Trust and between Fairness (win-win) and Collaboration with respect to Hostile and Defensive positions. The Hostile individual pays more attention to changes in Trust, perhaps because he/she checks their Defensive position stubbornly, having ulterior motives (bad intentions). The Defensive individual adopts Blind trust more readily, which eventually leads to their demise. As expected, the Hostile individual is less motivated by an equitable collaborative relationship with the Defensive individual.

6.5.3 Another study

I also tested a group of participants who were organizing a food fair, and who had to work together before, during, and after (to wrap up the event) its implementation. I tested them before they got to know each other and afterward by way of my questionnaire.88 In addition, I measured the level of interdependence to see how it would fit into my model. Note that the group was small, and that it is impossible to draw sound statistical conclusions from it; note also that the group expanded, in fact, it nearly doubled between the start date (sample population = 14) of the project and its completion date (sample population = 30). Yet, I feel authorized to pen down some observations, within the inherent limits of such small (and changing) populations (Tables 6.6 and 6.7).

I observe that participants engaged in the project from an interpersonal point of view (see Appendix 5.3). They were quite excited about the project and tended to trust and collaborate with each other rather readily. After the food fair, levels of most constructs declined to a relational or even an interactional level (see Appendix 5.3). Note that the Hostile position was stronger at first. In the end, the ratio of Hostile position/Defensive position remained about the same, near or at k = 1.3. When the level of interdependence abates, so do the values of Trust, Fairness, and Collaboration.

These results are quite typical of how people react when they engage in a project and when they eventually become part of the transformation stage of the project whereby People’ then interact within the context of active and influential Plans’, Processes’, and Power’ structures. The reduction in levels of intensity for the constructs of Dependence, Trust, Collaboration, and Intention to stay in touch with others after the event is significant between the before and after periods (at p < 0.0589).

The law of Apprehension, checked by way of a factorial analysis, proved true again in the after period, once team members have had a chance to work with each other, as shown in Table 6.8.

Comparing component 1 and component 2, one can suppose that as apprehension (Defensive position/Hostile position) augments, the mobilization of the vital resources by team members fades out.90

I cannot relate these findings directly to Hostile and Defensive positions, but I can “guesstimate” that there is an element of such positioning in the way that team members in the food fair project engaged and disengaged with it. When put in an environment that does not require hostile or defensive reflexes, People still deeply rely on the core principle underlying these two contrasting coping mechanisms by way of adopting, most probably in an unconscious manner, either a Hostile or a Defensive position, or, more realistically, a nonsimultaneous mixture of both (leading to an ideal k ratio of 1.3).

6.6 Identifying hungry tiger (IP) profiles

Ideally, projects must be exempted from hostile individuals (so-called hungry tigers); they represent a considerable POV. It is thus important for the feasibility expert to be equipped with a means of detecting them.

I conducted a study with the objective of measuring Hostile (PIP) and Defensive profiles (A-X, A-R, and A-V), with the former (instrumentally hostile individuals or hungry tigers) measured by four known traits: calculative, cold, egoistic, and cunning. I also sought to measure such constructs as Apprehension, Trust, Fairness, Cooperation, and Intent to stay in the project.

6.6.1 The study

I approached 343 artists from 9 different one-time shows and asked them to evaluate their director using my questionnaire. I merged the results because the responses were almost identical across the nine directors, although I recognize the limits of such a procedure. The questionnaire had been used in a number of studies and had been meticulously tested for its psychometric value. For all constructs, except for the Hostile position/Defensive position, results are given in percentage, computed from a 7-point Likert scale. The constructs of the Hostile position and Defensive position are measured through five items each and results are computed on a 7-point Likert scale, but not transformed into percentages. Results for the Hostile position are also posted on a 7-point scale. The code “stable” refers to a self-assessment of stability.

The research took place during the 2010s in Canada. Fifty-two percent of the participants in the sample were female, 42% male, and 6% did not respond to the question about gender. Forty-two percent were aged between 18 and 30, 15% were aged between 31 and 44, and 43% were between 45 and 65 years old. The 343 participants were composed of nine groups, most of them musicians and other artists as well as support staff (e.g., stage set) who engaged in the project of producing a one-time show involving a choir and/or an orchestra. The team had rehearsals once a week for nearly a year and twice a week in the few weeks prior to the show. I distributed the questionnaire during a break between two sessions of a rehearsal three weeks prior to the concert with the approval of the project director. The team members were to evaluate their director and, embedded in the questionnaire, I included questions about the respondents’ profiles.

The following constructs were measured with respect to how the team members viewed the project director: the Hostile position, the Hostile profile (related to how much Apprehension the project director generated), Trust, Fairness (a sense of a win-win relationship), Cooperation, Conflict, and the Intention to stay in the project. The following constructs were measured with respect to the participants (how they themselves felt toward the project director): the Defensive position, A-X, A-R, A-V, the Stable as well as the Hostile position (potential for instrumental aggression), and Dependence.

My reasoning was that I would see the impact of a Hostile position on the perception of the director taking into account two measures of Apprehension: Hostile position/Defensive position and profile (PIP or “Profile of Instrumental hostility”).

The questionnaires were collected on the spot and analyses were performed using a “Statistical Package for the Social Sciences” (SPSS) 15 as well as Partial Least Square (PLS 4).

6.6.2 Results

I provide an analysis of my key findings segued from identifying the basic emerging model to examining the role of a Hostile position (the way individuals respond to perceived threats by using uncivilized behaviors), the creation of a project capability index (PCI), and the identification of Stars.

6.6.2.1 Main statistics

The main statistics obtained for the entire group was as shown in Table 6.9.91

These results indicate that for the entire team, their relation to the project director is mostly in a transactional/relational mode (with Trust, in particular, being at 75%; see Appendix 5.3), which means that the project director was mostly regarded as a “business” colleague rather than as a friend. I also observe that the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio (the reverse of Apprehension) of 1.3 corresponds to the standard k-value found in other similar research.

6.6.2.2 SEM model

I ran dozens of structural equation modeling (SEM) scenarios with the best model appearing as shown in Figure 6.9.92

The so-called estimators (β values) and the degrees of significance (p-values) indicate that this model is acceptable. The model reads as follows: self-confidence (the ratio of Hostile position/Defensive position, the reverse of Apprehension) has a positive impact on Trust. As Trust builds up, collaborative behaviors increase.93 This is encouraged by a sense of a win-win situation (Fairness) between the parties. As Collaboration takes place, the Intention to stay in the project gains ground; this, in turn, has a positive impact on Self-confidence. Dependence on the director (and hence on the project) serves as a moderating variable.

Conflict also serves as a moderating variable, this time between Collaboration and the Intention to stay. This may be somewhat surprising because many models assume conflicts have a direct negative impact on a group dynamic. However, as noted previously, conflicts within projects can have two sides: functional or dysfunctional. Therefore, it is logical to see that Conflict serves as a moderating variable because it will affect the Intention to stay positively or negatively depending on its nature and intensity. The reader may think of conflicts as if they were hurricanes. North of the equator, hurricanes rotate counterclockwise, but south of it, they spin clockwise, yet they both are hurricanes, which may cause heartbreaking devastation.

These results corroborate findings extracted from various projects that spread across cultures and decades. In the case of the Pendjari National Park Project in Benin in 1993, for example, it has been noted that a sense of trust leads to positive results while conflicts muster delays.94 Countless scholars highlight the fact that trust promotes team integration (Collaboration).95 Some recognize the fact that dysfunctional conflicts bear additional costs.96 Hence, at least two of the three elements of the triangle of constraints (time and budget) are afflicted by the dynamic exemplified in Figure 6.9.

Also of interest is the fact that the Hostile profile (PIP) equally serves as a moderating variable, this time between Trust and Fairness (the sense of a win-win situation). This means that a Hostile profile (in the sense that a profile is composed of a certain number of traits) does not cause conflict by itself, but rather impacts on the emotional (Trust) and cognitive (evaluation of Fairness or the sense of a win-win situation) views of the team dynamic. This also makes sense: for some people, certain personalities will be conducive to better interpersonal relationships, while for others, the opposite view prevails. Hence, profile by itself cannot explain hardships that may arise during the course of a project.

Rather, what seems to count more directly are the levels of self-confidence (the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio) and of the Hostile profile considered jointly. This is what I examine next.

6.6.2.3 The role of hungry tigers

I computed and compared all profile types (IP, A-X, A-V, and A-R; adding Stable as a check measure97). Anxious, escaping/avoiding and resistant-defensive profiles all showed a normal distribution curve when plotting the percentage of individuals versus intensity. PIP (instrumentally aggressive) and stable profiles displayed opposite trends, as shown in Table 6.10.

Unequivocally, when most people claim to be stable, the same people contend not to manifest instrumental aggression.

I ran some factorial analyses98 and found that Hostile position was an excellent discriminator between the groups, as shown in Table 6.11.

I observe that when the Hostile value is higher than the Defensive value, scores for Trust, Fairness (win-win), and Collaboration tend toward 1. However, when the Defensive value is higher than the Hostile value, (i.e., when one feels very vulnerable), the scores for these same constructs tend toward 0. Interestingly, in the first group, the Hostile position is negative and in the second, it is positive.99 This could well be an indication, albeit subject to more verification, that Hostile position is a key marker of the project capability construct.

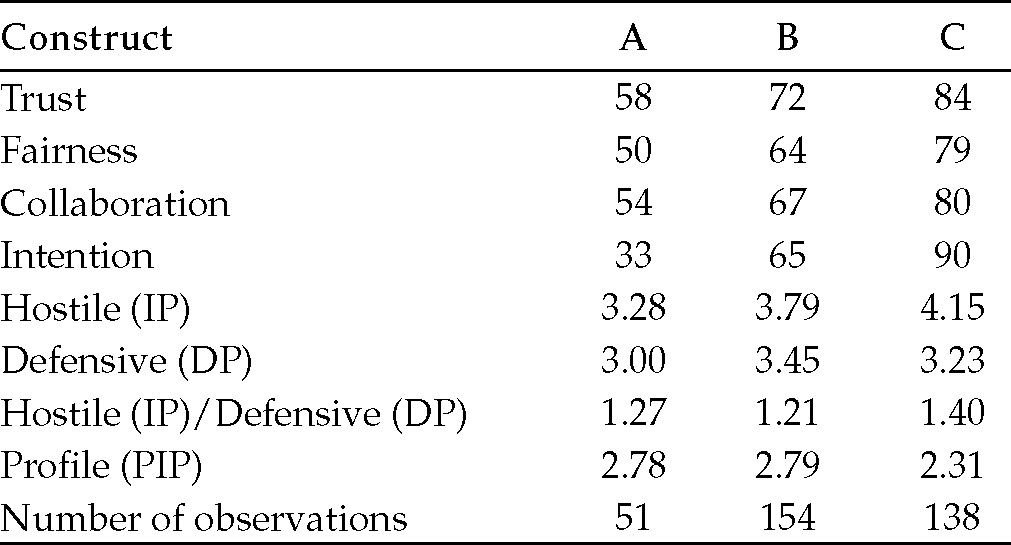

A discriminant analysis further tended to confirm the intricate part that the construct of a Hostile position plays in our six core competencies model (Table 6.12).

I find in the analysis that the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio is quite close for class A and class B; the same applies for PIP. For class C, however, the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio diverges by about 15% versus classes A and B, and the value of the Hostile position differs by about 18%. Furthermore, each class represents the three known interactional modes with class A being transactional,100 class B being relational, and class C interpersonal (see Appendix 5.3).

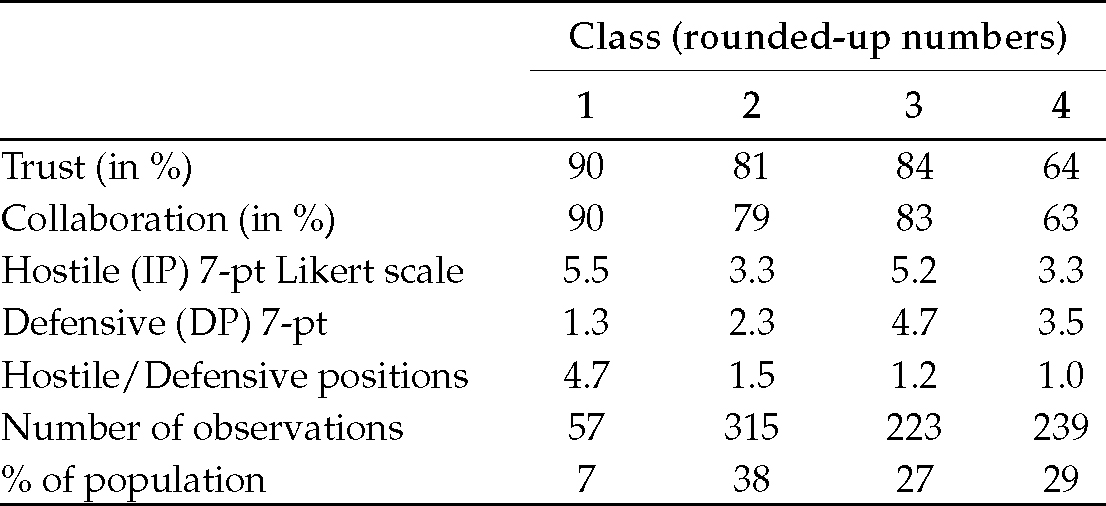

6.6.3 An index to separate the Stars from the average team members

Based on these findings, I developed an algorithm (the project capability index)101 that takes into account the Hostile position and the variance between the functional and actual Hostile and Defensive values, functional and real Hostile position/Defensive position ratios, and the three core psychological constructs: Trust, Fairness (sense of a win-win situation), and Collaboration. Since we had measures of Hostile and Defensive positions and Hostile profiles (PIPs), I suspected that I had enough information to separate exceptional (“top performers” or Stars) from average individuals (“others”).

Results show that the project capability index (PCI) sharply divides the top performers (the Stars and incidentally the most stable people) from the others, as shown in Table 6.13.

As can be seen in Table 6.13, the PCI discriminates well between the Stars (the top performers) and the others. Values of Trust, Fairness, Collaboration, and even the value of Intention, correspond to the most stable individuals, using an interpersonal mode (above 85%). This means that these individuals recognize the efforts for trust building, the sense of a win-win situation, and the collaborative endeavors sustained by the project director and “buy” into his/her performance; their Hostile position/Defensive position ratio is functional, at k’ = 1.56 (see Appendix 5.3). Their PCI value is approximately one-third that of the “other” group, those who are not Stars (not top performers). Standard deviations for the constructs do not have as wide a spread for the Stars (top performers) as for the others, which indicates that the former are more focused.

A factorial analysis further confirms the utility of the PCI, as shown in Table 6.14.

I observe that the “‘Stars 1”’ (top performers) have a higher construct mean (0.649). Also, when the PCI index is positive (0.035), values of Trust, Fairness, and Collaboration tend toward 1. Hence, the PCI index respects the law of Apprehension, which predicts that a functional Hostile position/Defensive position ratio leads to higher values for these important psychological constructs.

I performed another discriminant analysis, this time using the PCI and comparing the three groups (all participants: Stars and others), with the results in Table 6.15.

Since, according to my algorithm, the PCI must be under the value of 25, one can see that the top performers/most stable people are found in classes C (3 participants) and I (14 participants) for a total of 17 individuals out of 343, or 5% of the total participants. These two classes also record the best measures for all constructs as well as for the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio (albeit quite high for class C) and the score for a Hostile position (IP), which is expected since the PCI algorithm is based on these measurements.

Lastly, I decided to reconfirm that the two groups (Stars and others) were indeed significantly different, by performing a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Groups (top performers/stable vs. others) are indeed found to be significantly different at p < 0.05 on all constructs except Defensive Position DP at sig. = 0.999).

The PCI seems to effectively delineate those who are stable (called “top performers” or “Stars”) from those who are not as stable. This PCI allows us to establish subcategories among the “others” group, so that I can identify, say, the next 10 or 20 superior performers below the actual top performers.

6.6.4 Discussion

My results indicate that there are two distinct groups, called “top performers” and “others” (Table 6.16).

Top performers (Stars) display high values for the constructs of Trust, Fairness (win-win), and Collaboration. They tend to want to stay in the project longer than the “others” group. They feel a sense of attachment epitomized by high values of both Trust and Dependence.102 Their value for the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio is 1.3, which equals the standard k-value, and this value is half that of the “others” group (at 2.69). They also display much less standard deviation than the “others” group for all constructs, which means they are more focused. They show an excellent balance between the core constructs that are Trust, Fairness (win-win), and Collaboration. They are not geared toward conflicts.

Overall, the so-called top performers are the ideal employees in projects of any kind. They truly are the Stars.

Table 6.17 shows that for the same Hostile position/Defensive position ratio of 1.3 (the k-value), the two groups diverge quite substantially. The Hostile position and the Hostile profile appear to play a role that could explain this difference.

It can be noted that when the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio equals or tends to equal the value of the Hostile profile (1.29 in the last case, close to the k-value of 1.3), top performers stand out. In other words, stable employees are those who manage to find a fair and harmonious balance between their self-confidence level (Hostile position/Defensive position ratio) and their tendency to respond to threats (Apprehension) by way of instrumental hostility. Those employees are most likely to face project volatility with a mature and efficient response.

It can also be observed that for the same k-value of 1.3, the Stars (top performers) display construct values that are on average approximately 20% higher than that of the “in between” group. The Stars (top performers) tend to see the world in a more positive way and to have, from the start, a lower hostile profile. In other words, when the hostility level doubles, the perception of the world changes by approximately −20%. This tends to confirm a generally accepted view that unstable individuals likely view the world in more negative terms than stable individuals.

Most particularly, stable individuals have been found to share a number of characteristics that are highlighted in my results and discussion. High project capability individuals rank well on Trust, Fairness (win-win), and Collaboration. They are focused; they are well balanced emotionally, intellectually, and from a behavioral point of view (Trust, Fairness, and Collaboration); and they maintain their relationships for longer, and display little resentment. In addition, they have a functional level of self-confidence and are not geared toward conflict; they have a strong sense of attachment with the project and enjoy a positive vision of the world. This likely indicates that they will perform better (hence, my labeling of “top performers”). All these characteristics are in line with theories about secure personalities. In harmony with my argument, some authors make the following comment:

A large literature indicates that secure people engage in positive, intimacy-promoting, and tension-reducing interpersonal behavior, and have a positive memory bias for interpersonal exchanges. In contrast, avoidant people are relatively disengaged during social interactions, easily become bored or tense, and are likely to forget their partner’s feelings and remarks.103

The authors mention that stable people “try not to become either positively or negatively emotional.” Antsy people have a hard time forgiving; they juggle between positive and negative reactions and debate between their need for closeness and their need for self-defense. They resort to negative self-assessment.

Stable individuals are flexible and respond to the needs of others. They privilege people first, rather than tasks. They are predictable and use a heuristic logic, taking into account a large view of the world rather than a padlocked, somber view of it. They do not display episodic mood changes or unexpected variations in their decisions. They are usually better at developing their own talents and tend to excel academically and/or in extracurricular activities. They are able to concentrate, are not bothered by negative thoughts or souvenirs, and don’t feel victimized by events or by others.104 Rather, they show control in their cognitive, emotional, and conative processes. Some authors report quite succinctly on the difference between stable individuals and the “others” by way of the following results obtained from their own research.105 For what I judge the construct of Trust to be, the following traits are proposed (with a valence evaluation in parenthesis): trustworthy (0.95), caring (0.91), responsible (0.91), attractive (0.79), and confident (0.63). For Fairness: emotionally stable (0.91). For Collaboration: sociable (0.90) and intelligent (0.70). Finally, for Hostility: dominant (-0.30), unhappy (-0.70), aggressive (-0.75), mean (-0.78), threatening (-0.78), and weird (-0.85).

In summary, stable individuals have a good grip on their hostile tendencies, both in terms of action (k) and their general demeanor or general level of hostility (IP). These people are likely to outperform others. They represent the ideal candidates that a manager would want in a volatile environment, the likes of which are common in contemporary international projects. They are also the ones that should most likely be identified from the get-go and rewarded so that others can follow their tracks. As a manager, wouldn’t you agree?

I strongly suspect that my measures associated with the Hostile position/Defensive position ratio and Hostile profile are not only ingrained in the brain (most particularly, in the hypothalamus and the PAG for the coping mechanisms), but that they are part of the evolution of human nature. As DSM-IV notes when referring to human beings at an early age: “From the evolutionary model presented earlier, trust and mistrust represent facets of the pleasure and pain constructs, generalized to “adaptational” venues within the physical environment (…).”106

People who have a better perception of the quality of trust to attribute to others are likely to be less defensive, that is, they are likely to be more open and to find instrumental hostility unjustified. This behavioral disposition, in turn, generates a climate that is conducive to a friendly atmosphere,107 which then forges a better working environment.108 People who gain trust and respect interdependence are likely to face risks (and thus the threats that are part of volatile environments) and apprehension most effectively. As it has been pointed out in the context of supply chain management: “Trust must exist in an alliance since there is interdependency between the parties to mutually achieve goals (…) trust needs to exist for allies not only to share critical strategic information.”109

Some scholars have demonstrated that two characteristics of stable individuals—meticulous problem-solving and positive reappraisal—lead to satisfactory outcomes in a significant way when it comes to interpersonal relationships.110 In a more recent study, it has been shown in the context of buyer–supplier industrial relations, that levels of trust are highly correlated to positive performance.111

Overall, it appears fair to say that stable employees are likely to perform better, or at least to engage in more productive relationships with their peers. The PCI seems to be a strong predictor of such a positive outcome.112 Of course, the challenge for the feasibility analyst is to identify the Stars (top performers) ahead of time; this is only achievable by examining past records or by developing tests based on scenarios that would highlight hostile personalities and hostile profiles, as well as through interviews.

6.7 Functional and dysfunctional FPnc

The previous section examined top performers, that is, Forces of Production that excel—the Stars. I now discuss the Unfits (uncontrolled Forces of Production, FPnc): the Forces of Production that may block the development of a project. The Unfits (FPnc) may perform a variety of actions that prevent others from completing their tasks in three ways: they affect their mobility by delaying the action plan or by transmitting erroneous information, they hold possession of assets such as valuable information or even material or equipment, and they slow down or attempt to stop activities scheduled for the day. There are two types of FPnc:

Those that are functional

Those that are dysfunctional

Functional ones have a hostile profile and have found a way to adapt to their environment in order to maximize their selfish gains.

Dysfunctional FPnc present anxious, avoidant, or resistant-defensive profiles that are completely distinct from general behavioral norms and that cannot bring about a positive contribution to a project. Functional FPnc are hard to detect while dysfunctional FPnc stand out. Overall, both types of individuals are Unfits.

Often, functionalnc are willing to wait in order to get a sense of reward from their action. They plan for long-term, self-centered gains. They often go undetected, thus representing a significant POV, because they can at times excel at executive functions and in displaying goal-oriented behavior (which is why they are functional). Functional FPnc display weaker responses than others to disturbing emotional information113 that could affect a project. Because they at times do not seek material gain, longing instead for other forms of gain such as mere power,114 they are not necessarily sensitive to financial rewards and may not be willing to adjust their behaviors to fit the needs of the project. They have their own agendas—they belong to the Instrumentally hostile category. Functional but uncontrolled in some sense, these Forces of Production respect social norms, but will brush them off when convenient to do so.115 They are often charming. They may dream of taking charge of the project, but they don’t tend to reveal their intentions; they may play the “diva” when this meets their objective. They are known to excel at conceptual and linguistic tasks. This alone separates them from the dysfunctional Forces of Production,116 as the latter tends to fuss rather than to charm. If I were to test the functional FPnc, I would probably find that they rate low on the Hare psychopathy checklist—revised (PCL-R) scale117 on dysfunctional psychopathology. Yet, functional FPnc share the four fundamental traits of psychopathology as mentioned before: they are (1) calculative (manipulative) in their collaborative efforts, (2) cold (they show little or no empathy) in their approach to control and transparency, (3) selfish when committing to projects, and (4) sneaky (deceitful) in their trust-based relationships. Some authors refer to Machiavellian tendencies.118 Perhaps this terminology resonates with the reader; in any case, most project managers or team members have been confronted with such types of individuals and their shenanigans.

In stark contrast, dysfunctional FPnc cannot hide; they exhibit their antisocial behavior right away.119,120 They are reactive in nature—they belong to the defensive category as defined previously. They don’t plan; they merely react emotionally to the situation, at times in the extreme.

Recall my model of the six core competencies (Figure 5.4). I found that the construct of Control/Transparency (or equivalently, the Hostile position/Defensive position construct) had a direct one-way link to Trust. There was no direct feedback arrow to the construct of Control/Transparency (Hostile position/Defensive position or the reverse of Apprehension) from the construct of Trust. This forces the entire psychological mechanism to go through the process that sees Trust leading to Collaboration with time, and with Fairness being a mediating variable. Collaboration encourages (C+) Commitment, which then is followed by a feedback loop stretching from Commitment to the construct of Self-confidence (the opposite of Apprehension). This means that functional and dysfunctional Forces of Production (FP) eventually get exposed at some point, most likely during the most pragmatic stages of a project, which call for commitment and whereby tasks are to be completed imperatively. Indeed, there is no other way around it because, again, Trust does not feedback directly to the construct of Self-confidence (or its reverse: Apprehension). I found this by way of numerous macroanalyses spread over many years of research. Interestingly, the anatomy and physiology of the brain corroborate this flow (see Appendix 6.1). As seen before, the hypothalamus (the center for apprehension) does feed the pituitary gland (from which emanates, directly or indirectly, the key hormones relating to the four coping mechanisms), but the pituitary gland does not feed back to the hypothalamus. Hormones have to go through the entire blood system before reaching the hypothalamus again. What I am saying here is that the essence of the six core competencies model may be supported by neurobiological evidence. For me, this is good news: I estimate that the brain works much like a production process121 with its specific parameters (e.g., those ingrained in the hypothalamus such as body temperature, energy level, heart beat, hours of sleep, and sexual desire) and flows of activities (like that of hormones). Naturally, this flow has to transpire in the way people (read: FP) behave, and this is exactly what I have discovered.

As an example, it has been found that antisocial individuals (FPnc) typically show significantly reduced prefrontal activity;122 this is in line with what is to be expected from our model. On the other hand and to paraphrase some authors,123 functional FPnc perform differently; they can meet “specific computational demands” and excel at “representation, valuation, action selection, outcome evaluation and learning.” There are other marked idiosyncrasies between functional Hostile (functional FPnc) and defensive, dysfunctional FPnc. Appendix 6.1 compares hostile (instrumentally hostile individuals) and defensive psychological constructs and their accompanying brain structures. Hostile individuals show little changes in their vegetative system before attacking: a slow cardiac rhythm allows them to tolerate stress more effectively. The ability to keep their “cool” in the presence of high stress conditions may even encourage the employers to hire such individuals as project managers. Indeed, panic leads to more errors in decision-making:124 dysfunctional FPnc threaten projects and, additionally, tend not to learn from negative experiences.125 Overall, functional FPnc seem much more attractive than dysfunctional FPnc; the problem is that they are a potent source of headaches because of their hidden agendas. They are, indeed, invisible POVs.

6.7.1 A study and its results

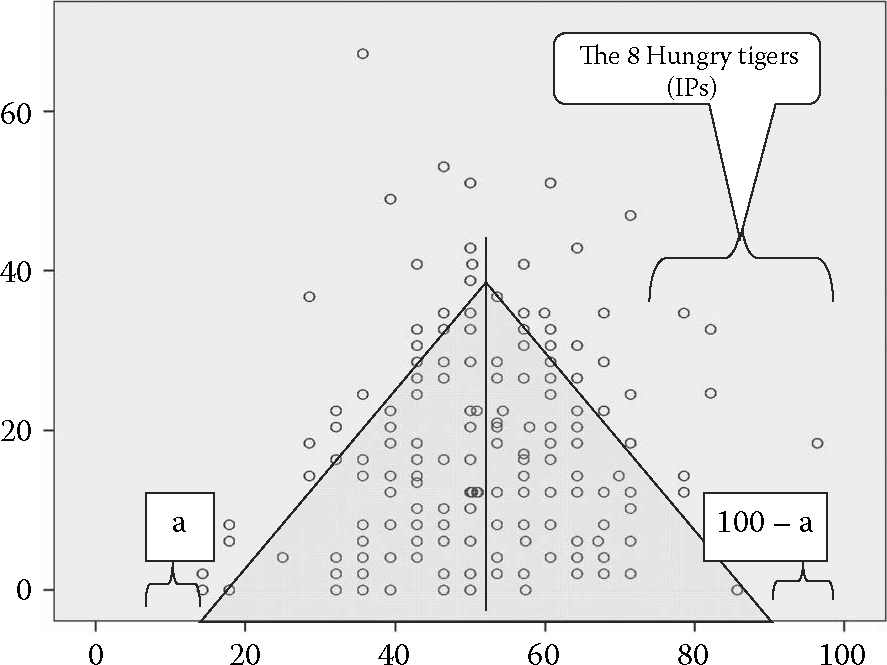

In one of my studies, I found the distribution for a group of 191 participants (shown in Figure 6.10).

Where the x-axis is the self-perceived hostile profile. Eight participants out of 191 definitely fall within the “pure hostile profile” (but none appear at the extreme value of more than 6.75/7.00; this is to be expected, if it were the case, they would have been kicked out of the team and maybe would already be spending time in jail!). This represents roughly 4% of the sample population, that is, 4% of people admitting (unknowingly) to have a pure hostile profile. This is in line with our observation made in Chapter 1 that every project contains at least 4% POVs. Interestingly, 5%–10% is the average known level of violent individuals in most societies since the sixteenth century.126

The majority of people prefer to be seen as “low-hostility individuals”, or else are “low-hostility individuals” because their response is below the middle point of 4 on the Likert scale of 7 points. Yet, the majority of people are neither overly feeble nor overly bellicose. In either case, they would be completely dysfunctional within the project. In fact, most answers range between 2.5 and 4.5, with the majority being close to 3.5 on average, signifying a docile temper that again is to be expected within project teams. I conducted various statistical studies on this sample group (n = 191); I present the results in the next sections.