Budgeting and Baselining Your Project

Projects are investments. In the charter we started to look at the benefits of a project and in the work break structure (WBS) we looked in more depth at exactly what we will create with the project. Now it is time to understand what it will cost us to create all of those deliverables. During project selection and chartering, very rough estimates of cost were considered to determine if the project’s benefits would be worth the investment. Now, in the detailed planning, more comprehensive cost estimates are developed to once again determine if the project’s benefits are worth the investment. Additionally, the project budget will be used to manage cash flow and guide decisions about how to use resources on the project.

Project planning is iterative and, as such, you would likely do a bit of budgeting before you determine all the details of scheduling, assigning workers, and planning for risks. For convenience, we will cover all of the cost estimating and budgeting work in this chapter, but keep in mind the fact that you generally need to finalize the other planning before you can finalize the budget. We will also describe at the end of this chapter how to consolidate the schedule, budget, scope, risk, and resource plans into one integrated whole.

The purpose of this chapter is to help you:

1. Estimate all project costs at the level of detail needed.

2. Assemble all of the costs into a time-phased budget that can be used for project control.

3. Consolidate the completed schedule, budget, scope, risk, and resources into an integrated project plan which you will use to baseline and then kickoff the project.

The completeness and accuracy of the inputs you have in terms of scope, WBS, schedule, and resources will largely determine how accurate your project budget will be.

In estimating project costs, we not only estimate how much it will cost to create all of the project deliverables, but how much it will cost to use them for their intended life and then to dispose of them responsibly. This is called life cycle cost and has become more important as more people and organizations have begun to focus on sustainability.

In the spirit of sustainability, we now frequently use the triple bottom line when we consider project investments. That is, how will this project impact people, planet, and profit? Projects have always sought to generate profit. This has been considered directly in the form of costs (usually in trade-offs with schedule and performance). In recent years, project managers have become more attuned to the needs and desires of various stakeholders including suppliers, customers, neighbors, regulating authorities, team members, etc. The triple bottom line dictates that we understand the costs (financial and other) to each of these stakeholders. Planet is the third part of the bottom line. While some things we may do to help the planet are expensive, other ways of trying to protect the planet can save us money. For example, careful planning helps us to use our resources more efficiently, and considering the life cycle cost of what we create may allow for operational and disposal cost savings that more than offset production cost increases. In addition, this life cycle cost approach is consistent with the Project Management Institute’s Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct in respect to the values of responsibility, fairness, and honesty.1

Costs can be divided simply into direct costs and indirect costs. Direct costs will not be incurred unless the project is undertaken. These include labor and materials. There are often other direct costs such as facilities or equipment that is acquired specifically for a project. Indirect costs, on the other hand, are ones that will be shared by a project, but that the parent organization will incur with or without the project. Utilities and equipment or facilities that are already part of the organization are often treated as indirect costs. These costs are allocated partially to the project and partially to other uses. If project budgets need to be established and monitored in your organization, you should understand what these costs are and how they are determined. Costs can also be divided into fixed costs and variable costs. An example of a fixed cost is purchase of a computer for your project and the cost is the same, no matter how much you use it. An example of variable cost is labor where you pay for each hour of effort.

Three commonly used methods of estimating costs are analogous, parametric, and bottom-up. Analogous estimating means estimating based on data from past, similar work activities. The more similar your past and present projects are—in terms of scope, duration, size, complexity, etc.—the more useful this type of estimate will be. This type of estimating isn’t costly and doesn’t take much time. You simply compare your upcoming project to a recently completed one and ask how the new project is similar to and different than the previous one. You take the actual cost of the previous project as a starting point and ask how is the new one bigger or smaller, more or less complicated, and how much those differences will impact the cost. The flip side to the benefit of being easy is that analogous estimating is not as accurate as other estimating techniques. Unless your project is simple and extremely similar to a past project whose actual cost data is easily referenced, you should probably not rely on analogous estimating as your only tool during this stage. Analogous estimating is often used during project selection, since using ballpark estimates is the only practical method until more project details are decided.

A second common estimating technique used in project management is parametric estimating. Parametric estimating uses historical data and project scope to create a mathematical estimate for duration or cost. For example, on a construction project that is 10,000 square feet, a parametric estimate would multiply the square footage by the given price per square foot to come up with a cost estimate. Or, on a complex software project, you may determine that the average programmer can write 10 lines of code per day, so it will take 80 days’ worth of work to complete 800 lines of code. You may go further if you know you have four available workers by deducing that it will take the four of them 20 days (80/4 = 20). Parametric estimating can be quite helpful, but its results are dependent on good data and knowledgeable application.

Parametric estimating can be taken to another level of detail by asking about features in a project that significantly impact cost. For example, if you were determining the cost to build a house, you would take into account not only total square footage, but also the number of bathrooms, whether the kitchen counters will be granite or a less expensive alternative, whether or not the windows will be high efficiency, etc. These factors collectively will quickly help an estimator develop a more accurate estimate. Depending on the need for accuracy, this may be sufficient or an even more detailed estimate may be needed.

The third method is bottom-up estimating, which includes identifying every element of cost (generally by using the WBS as a reference) and adding them up. This is potentially the most accurate form of estimating as you hopefully include the cost of every single project element. However, it is critical to double check because if any element is missing, that portion of the project is underestimated by 100%. Generally some elements of a project are overestimated and others are underestimated and, if the estimator does not have a consistent bias, they may somewhat offset each other. However, if any element is not included, it would take quite a few overestimates to offset it! Many experienced estimators will conduct both a parametric estimate and a bottom-up estimate, so the parametric one can serve as an indicator that something may have been missing from the bottom-up estimate if there is a large discrepancy.

If you know that you will need to spend money on a particular item, estimate it and include it in your project budget. There are situations, however, in which you may or may not need to spend money. Some are for risks that you know about, but do not know if they will happen. You will need to address these as well. Money for these “known unknowns” is called contingency reserve. The contingency reserve is included in your project budget but is held in reserve until and unless needed. An extremely heavy rain in a climate that may or may not experience such a deluge during the time the project is being conducted is a known unknown.

There are other risks on many projects that are just not envisioned. These “unknown unknowns” are things that seem to come out of the blue. Money for these is considered management reserve. It is not estimated directly—and therefore not included in the project’s budget, but must be considered part of the funding requirements. Therefore, project managers need to forecast based on history of similar projects about how much extra money should be included for management reserve. Generally, before this money can be spent, a project manager needs to justify it with a change order and a sponsor may need to approve it. An earthquake that is completely unexpected where the project is being conducted is an example of an unknown unknown.

If by the time you have estimated all of your costs and considered both types of contingencies, your organization does not have enough money to fully fund your project, one alternative is to conduct value engineering. That is, review the entire project by asking if all of the features and functions are truly necessary and also asking if there is a less expensive way to accomplish any of the project goals. Value engineering may slow the project planning, but it will often save significant money by eliminating nice-to-have features and using alternative approaches.

Many projects are constrained by money—both on an overall basis and on a cash flow basis. Therefore, it is important to understand how the budget will impact both the overall project scope and the day-to-day schedule.

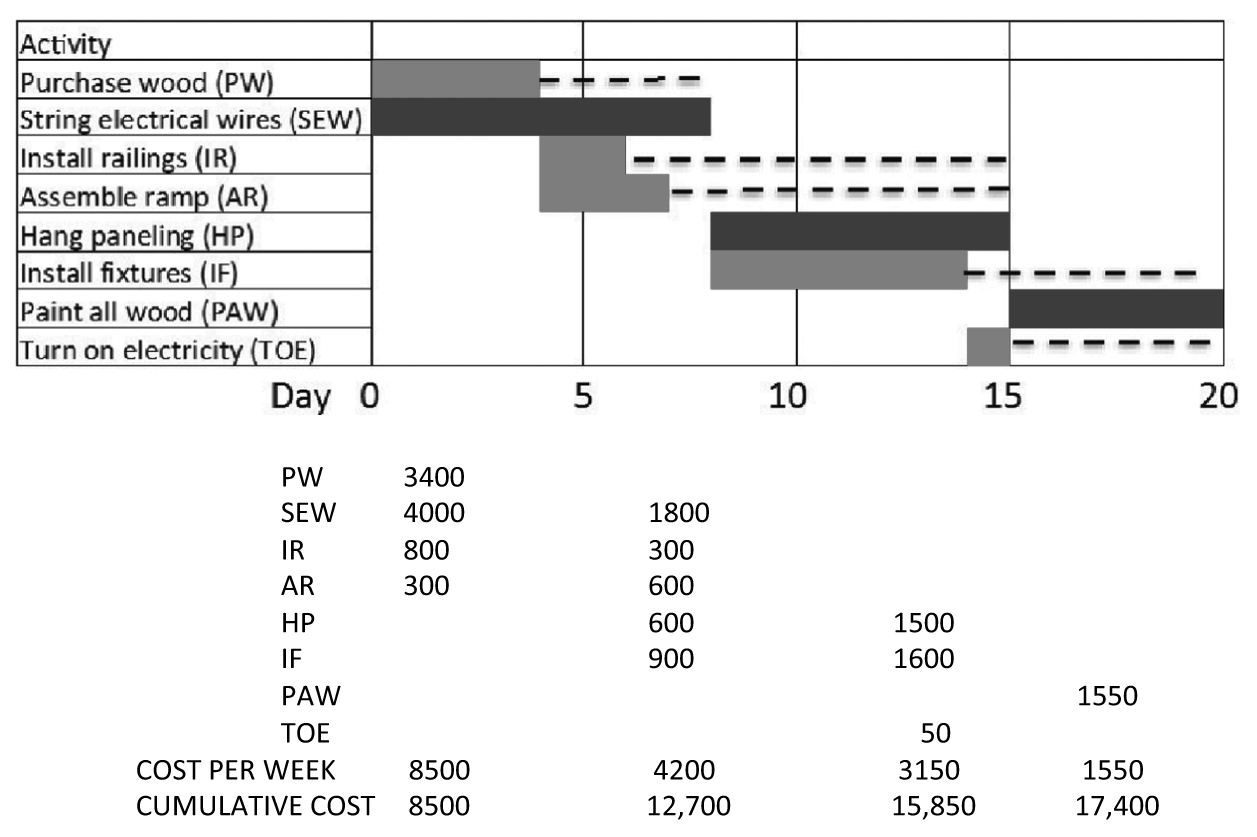

To establish a project budget, you first must know what all of the project deliverables are (identified in the WBS), what activities are required to create those deliverables (identified and put into chronological order in Chapter 5), and when each activity is scheduled. Some activities have only variable cost such as labor, while other activities have both fixed cost (such as equipment) and variable cost. We will continue with the same example we used to demonstrate scheduling. Some activities will have fixed cost and all will have variable cost. For simplicity, the fixed costs will be assigned when the activity starts, while variable costs will be assigned for each day of work. The overall project budget is $17,400 as can be seen in Exhibit 6.1.

Exhibit 6.2 shows the cash flow needed for the project. This example shows the original schedule (without certain activities delayed to level the resource demands). The first part of the exhibit is a Gantt chart that shows when each activity is scheduled. Note the vertical lines denoting weeks. Many project budgets are divided into either weeks or months. Directly below the Gantt chart is a table showing the cost for each activity on a weekly basis. For example, the first activity (PW) has $3000 of fixed cost and $400 of variable cost ($100 per day for four work days) assigned in the first week for a total of $3400. The next activity, string electrical wires (SEW) spans two time periods with the fixed cost and five days of work in the first week and the remaining three days of work in the second week.

Budgets as a Basis for Control

The costs for all of the activities are shown both on a weekly and a cumulative basis. Since there are four activities in the first week, the total cost is $8500. In the second week, an additional $4200 is budgeted, so the cumulative total for the first two weeks is $12,700. This cumulative budget will form the basis of cost control. Note that this project requires quite a bit of cash early on, as there are significant fixed costs for some of the materials during the first week. If the required amount of cash is not available that soon, some activities (and likely the entire project) will need to be delayed. A total cost curve is depicted in Exhibit 6.3 to show the cumulative budget. In Chapter 7, we will use this cumulative budget with earned value to show how to determine how well your project is doing in terms of both cost and schedule.

Project Cash Flow Example

Cumulative Cost Curve

Consolidate Schedule, Budget, Scope, and Resources into Integrated Plan

It is now time to pull all parts of your project plan together into one integrated whole. If your project is small and simple, you may have been integrating cost, schedule, resources, risks, and scope all along. However, on more complicated projects, sometimes different people plan different portions. If so, put them all together and ensure they make sense as a whole.

On a large or prominent project, there may be a ceremonial kickoff/ photo opportunity such as a ribbon cutting or groundbreaking with the company president and a golden shovel. Whether or not your project generates this type of publicity, the most crucial parts of a project kickoff occur behind the scenes.

When you are ready to transition from project planning to execution, you should gather your project team, sponsor, and as many key stakeholders as possible for a kickoff meeting. There you will review the project plan, assign responsibilities, and generate excitement about starting the actual project work.

Baseline Consolidated Project Plan

Once all of your stakeholders have agreed to your project plan, you need to consider the plan a commitment. You have promised to create the listed deliverables to the agreed-upon quality standards, by the agreed-upon date, for the agreed-upon budget, and with the agreed-upon resources. Now you need to deliver on your promises!

The concept of baselining is helpful here. All of the planning documents were drafts until the entire lot was approved. A baselined plan means that from this point forward if anyone requests a change, the request will need to go through a change management process and, if approved, the impact on budget and schedule will change the baselined plan. Just as the agreement means the project manager and team need to deliver as promised, the stakeholders cannot change their minds now without paying for their decision. Thus, the baseline protects both the people conducting the project and the stakeholders of the project.

In Summary

The three types of cost estimating used in project management are analogous, parametric, and bottom-up. You should use one or more than one of these, depending on your project’s size and level of detail needed, to create a cost estimate of all the project work you will be performing. Be sure to consider both indirect costs as well as direct costs and to include both contingency and management reserves proportionate to the risk involved in your project.

In addition to creating an overall budget for your project, you will need to factor in the issue of cash flow. In other words, when do your costs need to be paid and how can you pay them on time to prevent a project delay? Once your project budget is complete, you should consolidate it with your other project plan components, namely the schedule, scope, resource, and risk subplans. Together, these will make up your baselined project management plan that you will use to conduct the rest of the project work and which can only be changed through a formal change control system.

Key Questions

1. What methods do you use to estimate all project costs at the level of detail needed?

2. How do you assemble all of the costs into a time-phased budget that can be used for project control?

3. How do you consolidate the completed schedule, budget, scope, risk, and resources into an integrated project plan which you baseline and then kickoff the project?

Notes

1. PMI Code of Ethics (2015).

1. http://www.pmi.org/About-Us/~/media/PDF/Ethics/PMI-Code-of-Ethics-and-Professional-Conduct.ashx (Accessed May 6, 2015).

2. Goodpasture, J. (2010). Project Management the Agile Way: Making it Work in the Enterprise. Fort Lauderdale, FL: J. Ross Publishing.

3. Maltzman, R. and Shirley, D. (2011). Green Project Management. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

4. Venkataraman, R. and Pinto, J. (2008). Cost and Value Management in Projects. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.