In order to complete project work, a project manager needs to continue to plan, both because there may not have been enough detail for all the required planning in the first place and because things change. The project manager needs to direct the work of the project team; monitor and control that work; and ensure that the quality is shaping up. As project manager, you maintain momentum on the project by monitoring and controlling risks, controlling the schedule and budget, and controlling changes. Project managers need to spend a substantial amount of their time managing communication, both by understanding communication needs and utilizing appropriate methods. Finally, project managers need to close the project by transitioning deliverables to customers; capturing and using lessons learned; and managing a handful of post-project activities.

The purpose of this chapter is to help you:

1. Direct and control the project work and the quality of the deliverables.

2. Maintain project momentum by controlling risks, schedule, budget, and changes.

3. Maintain effective project communications and successfully close the project.

Continued Planning and Directing

Remember some projects are planned in detail before they start (waterfall) and others have only high-level planning for the entire project at the start with more detailed planning in increments (Agile). Many projects use a bit of both methods, with the results of early work providing the needed information to plan later work in detail. That means many projects will require planning for later work as early work is being completed. Also, most projects will have changes in their environment that necessitate changes in plans. On effective projects, project managers will have at least some planning performed in advance but will also have flexibility to conduct additional planning as it is helpful.

On many projects, the project manager may personally perform some of the work activities and usually instructs project team members to perform other activities. Included in this work are to:

• create project deliverables;

• provide, train, and manage the project team;

• obtain, manage, and use needed resources; and

• do all of this while using approved standards.1

Hopefully the project plans have identified the needed people and other resources for the project. However, the project manager needs to continue to make sure each is available when needed and often needs to mentor some of the project team members. One of the standards a project manager should adhere to is whatever ethical guidance is provided within her organization. Some of the actions sponsors take to help project managers during project implementation, a project manager can in turn do on a more limited basis to help project team members. These include empowering individuals to make sensible decisions without second-guessing them, managing organizational politics, and removing obstacles to performance.2

Monitoring and Controlling Project Work

Monitoring a project means continually gathering information and using it to determine how well the project is progressing. Controlling project work is comparing actual work with what was planned and, if the difference is great enough, making needed adjustments. A project manager can accomplish both of these partially by spending little bits of time frequently (often daily) with people doing the project work. Seeing first-hand exactly what is happening is so helpful when making decisions. Some of this work can be accomplished using various tools such as earned value analysis (EVA). We will discuss EVA later in this chapter.

The sooner a project manager realizes a potential problem is brewing, the easier it generally is to solve. Therefore, wise project managers create:

1. a culture on their projects in which people are encouraged to quickly admit a potential delay or quality problem may be starting;

2. a method of clearly and quickly communicating the issue; and

3. a method of providing rapid help.

One method of accomplishing this is the use of a visible cue such as red cards. A worker who feels an activity he is performing may cause problems with either deliverable quality or another activity in the schedule posts a red card near his workstation and the project manager promises that either she or someone else will be there within 30 minutes to collaborate on solving the problem.3

There are two approaches to quality and both are needed. Quality assurance is proactively doing the right things such as having good systems and well-trained workers in place; using adequate materials and machines; and fostering an improvement mindset in which project team members are always asking what is working that can be repeated and what is not working that can be changed. Quality assurance is a forward-looking, managerial approach. Done well, it not only helps to create good quality, but also convinces (assures) stakeholders that the project work is well-planned and the present project manager and team are competent.

The other approach is quality control. This is more technical and backward-looking. Quality control involves looking at a specification and asking if the deliverable in question conforms to that specification. This is the test of whether the project products have been completed correctly. If a project team does a good job with quality assurance, quality control should mostly confirm that the work has been done correctly.

To maintain momentum on a project, a project manager and team need to control risk, schedule, budget, and changes.

Monitoring and Controlling Risks

During both initiating and planning, the project team identified possible risks, assessed them to determine which were great enough to have response plans in place in advance, and created response plans for those big risks. Throughout the entire project, a wise project manager and team periodically do those same three activities: identify more risks that may become known now but were not known during original planning; assess all identified risks to determine if they are significant enough to justify response plans; and create response plans when appropriate. Note, some earlier identified risks may now move from small to big with changing conditions and now need response plans.

Additionally, throughout the project, team members should be assigned to monitor each of the big risks. If there are multiple big risks, it is good practice to have each team member assigned to monitor one or two of the risks rather than make one person keep track of all of them. The person in charge of a particular risk can benefit from looking at an early warning sign, or trigger, that the risk event is about to happen. For example, on a construction project, an early warning sign of severe weather can be a weather forecast. In the same way, for each big risk the person responsible should ask what is an early warning sign and how can I continue to monitor it?

Once a risk event is imminent, the response plan should be put in place. It is often cheaper and easier to respond quickly than after a major problem happens. However, many times a risk event happens without early warning and a team needs to immediately put a response plan into place. Even worse, a risk event may happen that has no predetermined response plan and the team needs to quickly develop and implement a response.

Earned Value Analysis Terms and Definitions4

Earned Value Example Illustrated

Controlling Schedule and Budget

EVA is a technique used to monitor both schedule and budget at the same time. It is important to understand that a project can be doing well on one dimension and OK or poorly on the other. For example, a project could be ahead of schedule but either right on budget or over budget. Depending on your sponsor’s wishes, doing well on one and poorly on the other may be OK, but usually doing poorly on both is not. Some project sponsors are so eager to have a project completed, that if you can finish it early, they are willing to pay more than the original budget. Understanding your sponsor’s desires helps a project manager make decisions based upon EVA.

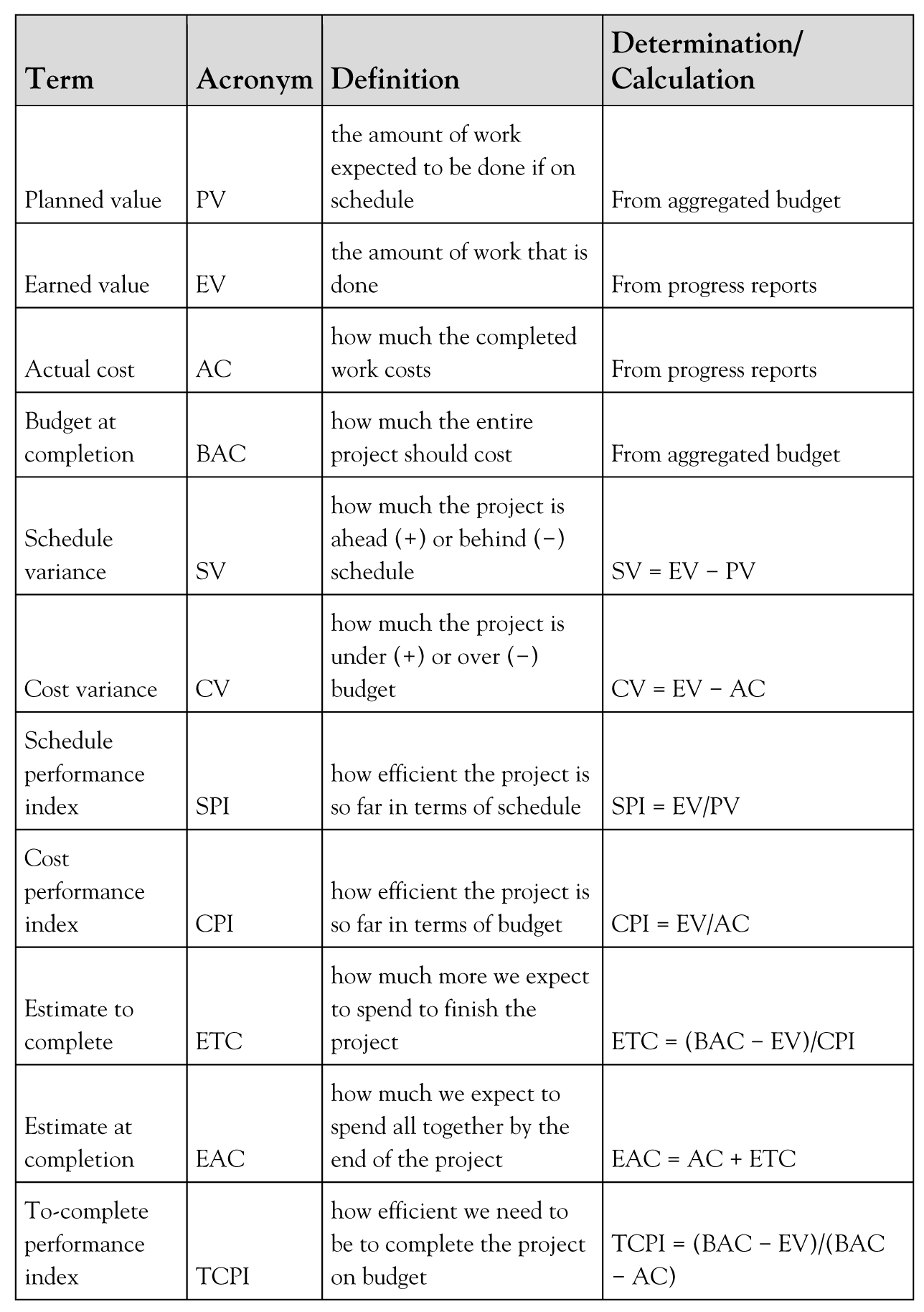

There are many terms used in earned value that require understanding. Exhibit 7.1 lists, briefly defines, and describes how to determine or calculate each of the terms. We will continue to use the same example project to understand schedules and budgets. The cumulative budget is depicted by the line graph in Exhibit 7.2 and the various earned value terms are shown. We will now demonstrate how each is determined.

From the project budget developed in Chapter 6 and shown on the graph, we can see that by now we should have spent and received (PV) $8500 and we can also see that our budget for the entire project (BAC) is $17,400. From progress reports (described later in this chapter) we can see that we have actually spent (AC) $10,000 and the value of the work that was completed as of now (EV) is $6000. Neither is exactly as planned (PV). Now let’s calculate how good or bad we are doing by using the formulas in Exhibit 7.1 and use those calculations to help us predict how we will do overall on the project if we continue our current trends.

SV = EV – PV

$6000 – 8500 = −$2500 (Behind schedule as we have accomplished less than planned)

CV = EV – PV

$6000 – 10,000 = −$4000 (Over budget as we have spent more than planned)

SPI = EV/PV

$6000/8500 = 70% (We have accomplished only 70% of what we planned to date)

CPI = EV/AC

$6000/10,000 = 60% (We have received only 60 cents worth of value for every dollar spent to date)

ETC = (BAC – EV)/CPI

($17,400 – 6000)/.6 = $19,000 (If we continue at our present efficiency, it will cost us an additional $19,000 to complete the project—more than our entire original budget!)

EAC =AC + ETC

$10,000 + 19,000 = $29,000 (If we continue at our present efficiency, the total project will cost $29,000—way more than our budget of $17,400!)

($17,400 – 6000)/(17,400 – 10,000) = 1.54 (We would need to improve our efficiency from our current 60% immediately to 154% to complete the project on budget—a tall order indeed!)

Perhaps when you first looked at Exhibit 7.2 you thought the project was just a little behind schedule and just a little over budget, but no big deal. EVA helps you understand early in a project how your present rate of completing work and spending money can be used to predict what your achievement will be by the time the project ends. It is a very powerful tool. If there are problems, the sooner in a project they are discovered, the sooner adjustments can be made to get back on track.

Many things change during the life of a project, and it is critical to understand which potential changes make sense and which do not. Agile projects handle changes mostly by planning just one iteration at a time in great detail and trying hard not to accept any changes within the iteration. Thus, changes are incorporated into planning for the next iteration.

Waterfall projects, on the other hand, often create plans for the entire project at the outset and need to respond to changes occasionally. Good practice on these projects is that all potential changes need to be requested along with the projected impact they may have on the project. Weighing these criteria, a decision needs to be made whether or not to accept each change. If the change request is accepted, the impacts to budget, schedule, and anything else need to be incorporated into updated plans and communicated to all impacted stakeholders. If the change is not accepted, the project manager needs to communicate that decision as well and make sure the person who wanted the change does not try to sneak it in anyway.

Since many people are busy when working on projects, it is much easier for a project manager to ask people to use simple change request forms such as the one shown in Exhibit 7.3. Note this form asks what the requested change is, why it is being requested, what impact it may have, and who will approve it.

Project Change Request

Date Proposed: October 15, 2015

Description of proposed change: Purchase wood from different supplier

Why is the change needed? The original supplier is both very late and way over the original budget.

Impact on Scope: none

Impact on Schedule: 3 day delay

Impact on Budget: save $2000.

Impact on Quality: none

Impact on Risks: may lessen, as first supplier is unreliable

Impact on Team: none

Date approved by:

Project Manager |

Sponsor |

Customer |

__________ |

__________ |

__________ |

We will continue to use the same project example. Remember, from our EVA we discovered we were both behind schedule and over budget. The carpenter is requesting permission to purchase wood from a different supplier. If this is considered a minor request, the project manager should be allowed to make the decision, but if it is major, it might go to the sponsor. If the project is being conducted for an external customer, perhaps that customer might want to retain the right to make the decision. It would be wise to agree in advance what decisions the project manager will be able to make and what decisions will be reserved for the sponsor or customer.

In your project planning, hopefully you developed a communication matrix as shown in Chapter 3. This outlines who you need to learn from and share with, along with logistical questions such as the most effective timing and methods and who on your project team is responsible. Now that you are implementing the project, it is time to more fully understand the communication needs and to utilize the appropriate methods to fulfill those needs.

Understanding Communication Needs

Many decisions need to be made on projects, and these require accurate, transparent, and timely information. The project manager, team members, sponsor, and other stakeholders all need to make decisions. A key judgment is knowing when enough information is in hand to make the needed decision. Projects often have significant time pressure, and decisions need to be made before all information is available.

Remembering that the most important success factor in projects is customer success, wise project managers try to keep their customers involved throughout the project. This requires frequent communication and effort. If the project manager and team show an eagerness to communicate and collaborate, stakeholders will believe they have first-hand, undistorted information, and they will trust the project manager and team.

Using Appropriate Communications

Three types of communications are especially effective for project managers: face-to-face conversations, stand-up meetings, and progress reports. Effective project managers spend a bit of time nearly every day in informal conversation with both their team and with various stakeholders. Many little things are discussed that would likely not be brought up in a formal report or meeting. Also, these frequent, informal chats are great for relationship building.

Although stand-up meetings have been used in many situations, they have been popularized with Agile projects. The idea is to have the project team get together daily for a short (perhaps 15 minute) meeting. As the name suggests, these meetings are intended to be short enough that no one should take a seat or get too comfortable! Each team member tells what he did the previous day, what he plans to do this day, how his work relates to other work, and any risks or issues he foresees. The meeting is not used to solve problems, but often two people who need to work together will do so right after the meeting.

Both face-to-face conversations and stand-up meetings can be more difficult when a project team is virtual. However, effective project managers will still attempt to accomplish the same goals of frequent exchange of information and relationship building using whatever means and timing they can.

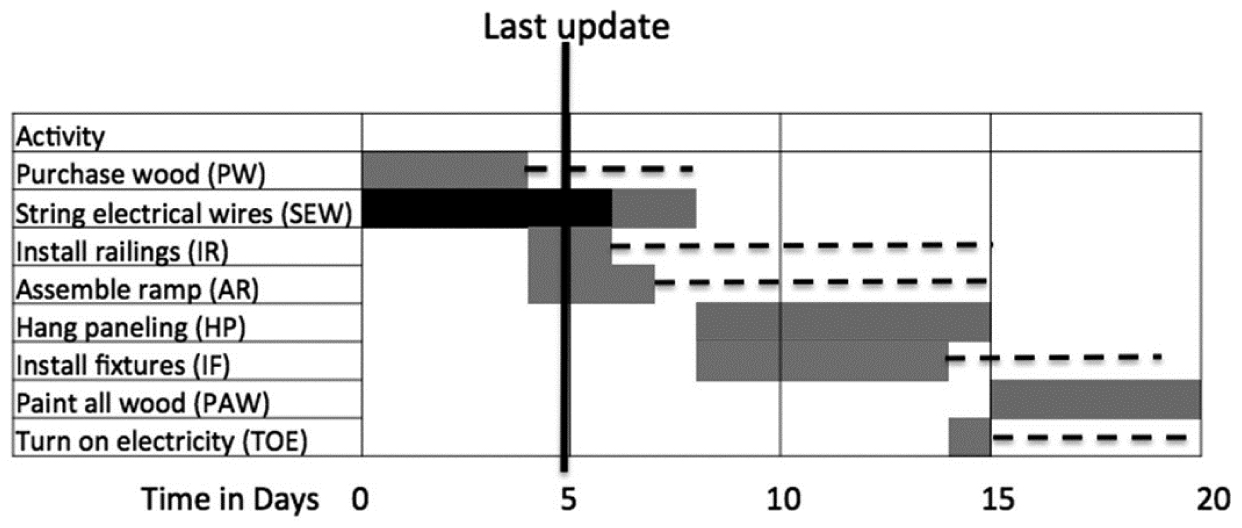

Most project sponsors and customers want to be assured on a regular basis that the project is progressing well. For this reason, progress reports are often used. Progress reports may be used with or without earned value as described earlier. They may also be effective if used with an updated Gantt chart to show how much progress has been made on each activity. An updated Gantt chart for our example project in Exhibit 7.4 shows that the second activity, String electrical wires, is one day ahead of schedule (shown by the bar color turned to black). Since that activity is on the critical path (denoted by the red color), that is good. However, the first activity, Purchase wood, has not even started and is now five days behind schedule. That also means that the next two activities, Install railings and Assemble ramp, are also not started as they need the wood.

One simple way to consider project progress is to look back at the previous time period, directly at the current time period, and forward to the remainder of the project. We will continue to use our example project to demonstrate this in Exhibit 7.5. This progress report spells out much of the detail behind the updates shown in Exhibit 74.

The time periods for this project are in weeks. Let us look back at the end of the first week. In this example, we were ahead on one activity (String Electrical Wires) and behind on the other (Purchase Wood) that were scheduled for this week. We start by reminding our sponsor or customer what they had approved for us to do during this time period and then compare that to what we actually accomplished. Any difference is a variance. Variances can be good or bad—ahead or behind schedule, over or under budget. In this example, we were five days behind on noncritical activity Purchase Wood, but one day ahead on critical activity String Electrical Wires. Although we are pleased to be ahead on the critical activity, we are five days behind on an activity with only four days of slack, so the project is a day behind. Because we do not yet have the wood, the next two activities are delayed.

We then look at the current time period, considering our actual progress to date, not just what we originally planned. For each activity (or milestone if you are reporting at the milestone level), we want to tell our sponsor about any risks that we are concerned about and any issues that will need to be decided. Since one supplier has held up an activity, we may need to consider a replacement. Also, one route for the ramp requires a bush to be removed, and we want the customer to make that decision. If we need to have a change approved from our original plan, now is the time. In our example, we need to find a new wood supplier and purchase the wood very quickly, and this will require approval.

Updated Gantt Chart

Progress Report

Most of our customers are quite concerned with when the project will be done (and often how much it will cost). For this reason, we project the remainder of the project at this point. Two of the remaining activities are not on the critical path, so we are OK with saying they will be behind the original schedule, but will still be completed in plenty of time. The other two activities (Hang Paneling and Paint All Wood) are on the critical path. If we can save one day on either one, we will finish on schedule. We have noted the risk that speeding these activities up may entail.

When a project is making good progress, these reports are simple. When a project is in trouble, these reports generate the kind of discussion that uncovers problems and helps to either get the project back on track or at least to give people realistic expectations going forward. We want to share any bad news early enough that adjustments can be made and the project can still be successful.

The point in time when project execution gives way to project closing is when the primary customer accepts the primary project deliverable. It is helpful to think of this as a transition rather than a single point in time. Project managers also want to capture and share lessons learned and to complete a few necessary post-project activities.

We want to create satisfied and capable customers. If you have kept your customer involved throughout the project, the deliverables are likely to be useful to them. We want to help the customer ensure that the deliverables work correctly and that the promised benefits are achieved. This may require some assistance in the form of demonstrations, instructions, training, and/or a website with frequently asked questions. A well-satisfied customer can be one of the most effective ways to secure future projects. It may be worthwhile after the deliverables have been used for some time (perhaps a few weeks or months) to assess how fully they have delivered on the promises that were made.

Capturing and Sharing Lessons Learned

The end of the project is a terrific time to ask what worked well that should be repeated on a future project and what could be done better on future projects. Capturing the lessons can be as simple as asking each team member to identify one thing that went well to be repeated in the future and one thing that should be done differently. Capturing lessons can be more involved also by reviewing project documents to follow the progress from creating the charter on through the project’s life cycle and asking at each point, what was learned. Project teams can do this on their own, and they can also ask customers, sponsor, and other key stakeholders for feedback.

These lessons should then be organized by topic and stored somewhere that is convenient for people planning and managing future projects. The lessons can be written very briefly, but a good practice is to include the name and cell phone number of the person who submitted the lesson, so future project managers can have an informal conversation when trying to apply the lesson. If your organization has a project management office (PMO), they should instruct you where and how to archive the lessons learned.

Completing Post-Project Activities

Project managers want to make sure they provide feedback on the work of their project team members to their respective supervisors. This may be informal since the supervisor probably is the person who formally evaluates his or her direct reports, but it is still good practice. There may also be some accounting, materials, equipment, or other issues to finish.

In Summary

Once the work of your project is underway, your role as a project manager is to monitor the project’s progress and ensure it is unfolding as planned. To determine progress, you will use a variety of techniques, ranging from informal communication with team members and stakeholders to quantifying your progress using earned value management (EVM). You will need to keep your sponsor and other stakeholders aware of this progress as well as any changes made to your baselined project plan.

To formally close your project, you must obtain acceptance of your project deliverables from your customer. Additionally, you must also close all administrative work and document lessons learned. Finally, best practice suggests you should assist in providing evaluations of your team members and helping them find new work.

1. How do you direct and control the project work and the quality of the deliverables?

2. How do you maintain project momentum by controlling risks, schedule, budget, and changes?

3. How do you maintain effective project communications and successfully close the project?

Notes

1. Adapted from PMBOK® Guide (2013), pp. 80-81.

2. Kloppenborg, T. J. and Tesch, D. (2015), pp. 29-30.

3. Sting, F. J., Loch, C. H., and Stempfuber, D. (2015), pp. 36-37.

4. Adapted from PMBOK® Guide (2013), pp. 217-223 and Kloppenborg, T. J. (2015), pp. 401-405.

References

1. PMBOK® Guide (2013). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (5th ed.) Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

2. Kloppenborg, T. J. and Tesch, D. (2015). How Executive Sponsors Influence Project Success. MIT Sloan Management Review 56(3), 27-30.

3. Sting, F. J., Loch, C. H., and Stempfhuber, D. (2015). Accelerating Projects by Encouraging Help. MIT Sloan Management Review 56(3), 33-41.

4. Kloppenborg, T. J. (2015). Contemporary Project Management 3rd ed. Mason, OH: Cengage Learning.

5. Marnewick, C. and Erasmus, W. (2014). Improving the Competence of Project Managers: Taking an Information Technology Project Audit. Proceedings Project Management Institute Research and Education Conference, Limerick, Ireland.