Partnership in Mental Health and Child Welfare: Social Work Responses to Children Living with Parental Mental Illness

SUMMARY. Mental illness is an issue for a number of families reported to child protection agencies. Parents with mental health problems are more vulnerable, as are their children, to having parenting and child welfare concerns. A recent study undertaken in the Melbourne Children’s Court (Victoria, Australia) found that the children of parents with mental health problems comprised just under thirty percent of all new child protection applications brought to the Court and referred to alternative dispute resolution, during the first half of 1998. This paper reports on the study findings, which are drawn from a descriptive survey of 228 Pre-Hearing Conferences. A data collection schedule was completed for each case, gathering information about the child welfare concerns, the parents’ problems, including mental health problems, and the contribution by mental health professionals to resolving child welfare concerns.

The study found that the lack of involvement by mental health social workers in the child protection system meant the Children’s Court was given little appreciation of either a child’s emotional or a parent’s mental health functioning. The lack of effective cooperation between the adult mental health and child protection services also meant decisions made about these children were made without full information about the needs and the likely outcomes for these children and their parents. This lack of interagency cooperation between mental health social work and child welfare also emerged in the findings of the Icarus project, a cross-national project, led by Brunel University, in England. This project compared the views and responses of mental health and child welfare social workers to the dependent children of mentally ill parents, when there were child protection concerns.

It is proposed that adult mental health social workers involve themselves in the assessment of, and interventions in, child welfare cases when appropriate, and share essential information about their adult, parent clients. Children at risk of abuse and neglect are the responsibility of all members of the community, and relevant professional groups must accept this responsibility. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2004 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Parental mental health, child welfare, social work decision-making, child protection, mental health social work, child protection social work, children’s courts

Meeting the needs of children in families with parental mental illness is a recognised and increasing problem. Developments in the mental health field have meant that more people with mental illness are being managed in the community. Moreover, contemporary social policy emphasises that people with mental illness should be maintained in the community and that those who are parents should be better supported to retain their children in their care. Parents with mental illness who have dependent children need considerable support and are therefore likely to be involved with a range of professionals and services. The precarious nature of mental illness can bring these families to the attention of child welfare services when the parent’s mental illness interferes with their capacity to appropriately care for their children. However, an awareness of the strong association between parental mental illness and difficulties in the development and psychosocial adaptation of their children has yet to lead to broad support for service initiatives that address the needs of both mentally ill parents and their children (Falkov 1999:7). Clearly not all children whose parents are mentally ill will experience difficulties. What is important to identify is what constellation of social and psychological factors in combination with parental mental illness will impact on child care and parenting and contribute to child abuse (Stanley and Penhale 1999).

Mental illness is an issue for a number of families reported to the Child Protection Service in Victoria (Australia) (Buist 1998), and the difficulties such families encounter challenge not only the families themselves but also the professionals who work with them. Community studies in the UK (Iddamalagoda and Naish 1993) have shown that around 60% of women with serious chronic illness have children under the age of 16 years; the same result was found from a 1998 survey of inpatients at Maroondah Hospital Area Mental Health Service (Victoria). Parental mental health problems were encountered in two of the major research studies included in the British Department of Health’s examination of the workings of the child protection system (Stanely and Penhale 1999:35). Gibbons, Conroy and Bell (1995) found that 13% of children of children on the child protection register across eight English counties were living in a family where their parent had been treated for mental illness. Lewis and Shemmings (1995) found a similar association: Nearly 20% of the 220 child protection cases they studied involved a parent with a mental health problem.

What the study reported on today sought to do was investigate to what extent adult mental health problems were present in children’s court matters, what difficulties these cases presented to the court, and child protection, and at how much mental health services involved themselves in the court process. A study I undertook in 1995 at the Melbourne Children’s Court (Victoria, Australia) revealed that the children of parents with a psychological disorder comprised one of the groups of cases that were regularly presented at Court (Sheehan 1997). In fact, twenty-five of the ninety-two child protection hearings observed over a three-month period at the Children’s Court involved parents with very poor parenting skills who might not have a recognised psychological disorder but whose difficulties as parents clearly involved mental health issues. The study reported on today set out to investigate if this is still the pattern.

THE STUDY EXPLAINED

The study findings are drawn from the child protection cases that Magistrates in the Melbourne Children’s Court, Victoria, referred to a pre-hearing conference during the first six months (January-June) of 1998. Magistrates refer child protection matters to a pre-hearing conference when a parent or parents dispute the need for the Court to make a child protection order. Pre-hearing conferences are conducted by a Convenor who generally has social work or legal training. Convenors’ appointments are formally made by the parliament but in practice are managed by the Victorian Attorney-General. The conference is held prior to any formal hearing so that the family, their legal representatives, and the welfare authority can see whether or not they can negotiate an agreement about a child protection order. Pre-hearing conferences were introduced into the Victorian child welfare legislation in 1994 in the belief that the use of a mediation process, with confidential discussion between the parties, could avoid difficulties inherent in the adversarial nature of court-resolved disputes.

There were 228 Pre-Hearing Conferences held during the first six months of 1998 (January-June). A descriptive survey of the Conferences was undertaken; the Convenors completed a data collection schedule for each case at the completion of the Conference. The data sought was both qualitative and quantitative. The survey schedule asked a series of standard questions about each case: the reasons for the child protection application, the nature of the child protection concerns, who were the participants in the conference, and the conference outcome. The information was drawn from what case information was available on the day of the Conference.

THE STUDY FINDINGS: PROFILE OF CASES

Of the 228 Pre-Hearing Conferences that comprised this study, 40 of these cases (29%) involved parents with mental health problems. The 40 cases involved 59 children. A case was determined to involve mental health issues when parental mental health problems were the basis of, or a significant factor in, the child protection concerns supporting the child protection application. This information was drawn from the child protection court report. Convenors noted on the data collection schedule whether parent mental illness was listed in the child protection service’s Court report as a fact contributing to the child protection application. Whilst the child protection service’s Court report might state that a parent’s mental health status was part of the basis of their concern for a child-or the entire basis of their concern–very often there was no clear diagnostic information presented in the report. Certainly there was no checklist of mental health problems that accompanied the child protection report. Child protection workers often struggled to find out accurate information about a parent’s mental health status, or a parent might conceal a history of mental health problems. Moreover, mental health problems associated with, for example, borderline personality disorder, did not readily fit the criteria for assessment and treatment in the public health mental health service. Child protection workers therefore found it difficult to get confirmation of their concerns or obtain advice about appropriate interventions from adult mental health professionals.

The child protection matters referred to a Pre-Hearing Conference included new child protection applications (n = 137); in 64 cases extensions of orders were sought; in 27 cases a breach of an existing child protection order was brought to court. Cases would either settle at the pre-hearing conference, be adjourned, or be referred to a magistrate for a contested hearing.

Of the 137 new child protection applications that came to a pre-hearing conference, 31 involved parents with mental health problems (43%). Twenty-four of the new child protection applications involved allegations of actual physical harm, or likelihood of physical harm to a child (S 63 (c)); twenty-five applications involved concerns about emotional abuse or the likelihood of emotional harm to a child (S 63 (e)). One case involved abandonment of the child (S 63 (a)); nine cases were based on a parent’s or parents’ inability to care for the child, eight cases involved significant harm, or likelihood of harm, to a child’s physical development or health (S 63 (f)); one case involved allegations of sexual abuse to a child (see Table 1).

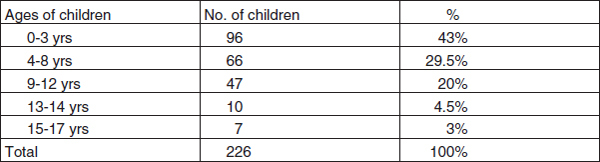

The children who were the subject of the 137 new child protection applications were predominantly very young, generally aged between birth and three years of age (n = 96), and at the pre-school age level (see Table 2).

The Child Protection Concerns

Cases involving parental mental health issues and child protection concerns were characterised by child neglect, domestic violence, financial and accommodation difficulties, family disorganisation, and relationship difficulties. What also emerged was significant substance abuse by the parent who had care of the child, and this appeared to exacerbate mental health difficulties. In the 31 cases that involved parents with mental health problems, from the 137 new child protection applications that came to a pre-hearing conference, concerns were presented to support the child protection application (see Table 3).

TABLE 1. Grounds for new child protection applications referred to a pre-hearing conference January- June 1998, Melbourne Children's Court. The Children and Young Person's Act (Victoria)1989 Section 63 sets out the six grounds on which a child protection application can be made. Very often two or three grounds may be made out to support the application.

Sheppard’s (1997) UK study found that mothers with depression were living in households pervaded by abuse and violence. Falkov (1996) found also, in his study fatal deaths in children, that domestic violence was a significant feature in the context of maternal mental health problems. The child protection concerns, in the majority of cases, in this study were grounded in similar concerns about adult functioning and focussed on the physical and psychological aspects of parenting. The problems included a parent’s incapacity to provide physical care for the child; financial and accommodation difficulties included the inability to maintain accommodation and transience, and consequent social isolation and lack of supports; and poor impulse control leading to unsafe consequences for the child. Family disorganisation and relationship difficulties included issues such as:

TABLE 2. Ages of children who were the subject of the new child protection applications referred to a pre-hearing conference at the Melbourne Children's Court, January-June 1998.

TABLE 3. Child protection concerns listed (number of cases involving parents with mental illness n = 31). Typically there are a number of concerns attached to each case, which are presented in the child protection service court report as the basis for the child protection concerns.

• the chaotic lifestyle of a parent,

• parent’s inability to get the child to school or to child care and to then collect the child, or to keep to access arrangements if a child was in foster care,

• parent’s physical harm to a child,

• parent leaving the child in the care of multiple others,

• exposing the child to physical and sexual harm by others,

• exposing the child to domestic violence,

• exposing the child to inappropriate relationships with others,

• the parent’s poor impulse control leading to unsafe consequences for the child,

• the parent’s overly harsh discipline of the child,

• the poor ability of a parent to understand the consequences of their actions,

• the child having the care of the parent, siblings, meals and other household responsibilities,

• social isolation/lack of stimulation,

• developmental delay in a child.

Other concerns raised by child protection workers, in these cases, included issues such as: a parent’s inability to acknowledge their mental health problems, the inability to negotiate with others about important issues (e.g., child care arrangements) and the lack of insight into their own or their children’s difficulties. Another issue was the unrealistic expectations a parent may have of a child, such as around child behaviour, responsibility, and independence. Older children involved in the cases also identified these issues as concerns and a number did not want to return to their parent’s care until the concerns were resolved. A smaller number of children (over 11 years) were themselves engaging in risk-taking behaviours.

Parental Mental Illness and Child Protection

The mental health concerns that brought the child to the attention of child protection overwhelmingly related to the child’s mother, who tended to have sole care of the child or children. In two cases both parents had a mental illness; in two cases it was the father who had a mental illness. The particular mental health problems present in the cases were variously described as a diagnosed mental illness such as schizophrenia (n = 11) or a psychotic disorder for which the parent (predominantly the mother) was receiving treatment, a personality disorder, in particular borderline personality disorder (n = 7)–which was variously described as depression, attachment difficulties or presented as problems with domestic violence, transience and/or anger management. One mother (of two children aged 4 and 5) with a history of psychiatric disorder was in jail. Three mothers had attempted suicide and had been hospitalised. Other individual cases included the attempted strangulation of a baby; shaken baby; factitious disorder by proxy (n = 2); one case in which the mother held the fixed belief that the father had sexually abused the child (this had been disproved on a number of occasions in the three-year-old girl’s life). The nature of the parental mental illness or psychological disorder was often not specified, unless a psychiatric assessment was attached to the court report or the parent was identified as a client of the adult mental health services.

Other concerns raised by child protection workers, in these cases, included issues such as: a parent’s inability to acknowledge their mental health problems, the inability to negotiate with others about important issues (e.g., child care arrangements), and the lack of insight into their own or their children’s difficulties. Another issue was the unrealistic expectations a parent may have of a child, such as around child behaviour, responsibility, and independence. Older children involved in the cases also identified these issues as concerns, and a number did not want to return to their parent’s care, until the concerns were resolved. A smaller number of children (over 11 years) were themselves engaging in risk-taking behaviours.

The concerns expressed by the child protection service most often related to the nature and consequences of the particular parental mental illness. Issues such as how poor concentration, lack of motivation, medication side-effects, and impulsivity affect a parent’s ability to participate in intervention and therapeutic programmes for their child and to carry through with agreements. Agreements made about, for example, engaging in treatment programmes, counselling services; agreements about the physical aspects of child care such as getting a child to school, etc. Adult mental illness brings with it other psychosocial problems, already noted; problems, perhaps, with financial management, maintaining accommodation, social isolation, maintaining employment. What was often clear in discussions about child protection concerns was that parents with significant psychiatric problems may struggle to understand their child’s developmental needs and struggle to understand how their disorder influences their parenting capacity. What was clear was also that there was a general lack of knowledge, by professionals including legal practitioners, of the long term nature of serious mental illness, its impact on the individual’s day to day functioning, and how that affects parenting. Previous findings by Sheehan (1997), that generally very little expert information was provided to the Court process by mental health practitioners; nor, did the child protection service refer to mental health knowledge and practice to explain their concerns about a child, are again confirmed.

In this study, in two cases, mental health professionals did attend Court, in their role as the case managers for parents. In so doing, they provided important information about a parent’s capacity to care for the child. In general, however, neither professionals nor extended family attended court in these cases, highlighting the lack of support networks and the social isolation that is commented on by professionals and in the literature. Apart from the child protection service and lawyers, only in two cases did grandparents attend. In six other cases, support workers from community agencies attended, and the Salvation Army chaplain attached to the Children’s Court attended as a support for a parent in one case.

The difficulties that bring children of parents with a psychiatric disorder to the attention of the Children’s Court are particularly challenging. The lack of involvement by mental health professionals in the child protection system meant the court was given little appreciation of either a child’s emotional or a parent’s mental health functioning. The lack of effective co-operation between the adult mental health and child protection services also meant decisions made about these children were made without full information about the needs and the likely outcomes for these children and their parents. When mental health professionals did attend court, generally as the case managers for parents, their focus was solely on the adult client, and they appeared to minimise parental responsibilities. There was a lack of expert information for the court about a parent’s capacity for rehabilitation, about the temporary or permanent nature of the disorder, what responds to treatment, what programmes work, and what do not.

How dependent child protection work is on cooperation from other professionals has been well-covered in the literature (Holt, Grundon, and Paxton 1998). Stanley and Penhale (1999), in their study of mental health assessments and child protection, found that social workers were often uncertain about how a mother’s mental health problems were impacting on their child, and that there was no consistency on professional input into assessments even if it was established that there was some impact. This might in part be explained by a sensitivity to maternal mental health problems and how they are characterised.

The different frames of reference and agency functions of adult mental health and child protection services appear to impede communication, and ultimately decision-making, about child protection cases (Holt, Grundon, and Paxton 1998:266). Moreover, how child welfare/child protection is conceptualised by services and their providers has a significant influence on service responses to families with a mentally ill parent. The Australian child protection system looks for single incidents of child abuse, or for actions that have precipitated a crisis in a family, to confirm the need for intervention. However, parents with mental illness, and their dependent children, will often have problems that are ongoing in nature, problems that are poorly accommodated by both child protection and adult mental health services, problems that may very well be exacerbated by bringing such problems to the Children’s Court.

System Responses

This inter-agency cooperation is difficult to obtain and, the literature suggests, bedevils attempts to assess adult mental health implications for dependent children (Holt, Grundon, and Paxton 1998; Reder and Duncan 1997; Buist 1998). However, Byrne et al. (2000) in their recent Australian study found that service providers did acknowledge difficulties and problems specific to parents with a serious mental illness and their offspring. It was the lack of liaison between agencies, and the lack of coordinated service provision, that was the barrier to effective service delivery. They found that, despite an awareness of the overall problem in working with parents with mental illness, very few agencies had written policy guidelines for the management of these clients. In fact details about whether adult clients had parental responsibilities or whether children were present in the home were not recorded on client files (Byrne et al. 2000).

The reasons why effective collaboration between the child welfare and adult mental health services might be difficult were canvassed by the Icarus Project (1998-2000), a cross-national study developed by Brunel University (England), to investigate the nature and level of support in the community for children and parents in families where there is parental mental illness. What was found was that the structural separation between mental health and child welfare services, each with separate governing authorities in Australia, is markedly different from other countries, in particular the Scandinavian and continental European countries. The lack of a shared discourse across the Australian system, and authority to cross service boundaries between child welfare and adult mental health services, means there are differing views about when parental mental illness constitutes a risk to a child. This hinders the development of practices that provide information about the whole family, and a more complete understanding of a family’s functioning, which will assist the legal system in its responses to vulnerable families.

Countries in which the two services were co-located, or where multi-disciplinary teams responded to child and family welfare problems, increased the potential for good communication between professionals (Hetherington et al. 1999). Where the professionals in the team could obtain information about the whole family, then a more complete understanding of a family’s functioning was possible. The more specialised the organisation of child welfare and mental health services became, the more likely it was to have barriers between services, over information, access to resources and to programmes. In Australia, the right of a parent to maintain that information about a mental illness is confidential is a source of conflict for both mental health and child protection services. Child welfare professionals commented that they found it difficult to discuss, and seek information about, the impact of significant mental illness on a parent and other family members. In Australia, many primary health carers would be reluctant to involve child protection services unless it was absolutely necessary, as social workers are regarded with some suspicion and closely identified with child removal.

Statutory intervention in families in Australia has to be legally justified rather than based on social work discretion. There is considerable emphasis on the importance of due process, attention to individual rights and legislative obligation. What this means in practice is a need to establish fault with parents, to permit the involvement of welfare services, rather than propose that need is the basis for the involvement of the child protection service in a family’s life.

How child welfare/child protection is conceptualised appeared also to have a significant influence on service responses to families with a mentally ill parent. The Australian child protection system looks for single incidents of child abuse, or for actions that have precipitated a crisis in a family, to confirm the need for intervention. Parents with mental illness, and their dependent children, will often have problems that are ongoing in nature, problems poorly accommodated by both child protection and adult mental health services.

The significance of developing services that will work together, and share knowledge frameworks and responsibility for children at risk, is pivotal to the effective functioning of child protection. Where the child protection system intersects with the legal system in order to protect a child from harm, it needs to provide the courts with reasons for its actions. To do this effectively and appropriately it needs to draw on the expertise of other professionals who work with families, and this will include mental health professionals, when parenting and family difficulties are the result of parental mental illness. Where there is little inter-agency collaboration, problems such as those evident in the study described herein, impede decision-making.

Falkov (1999:19) identified a number of important principles in working with families in which there is parental mental illness. Principles, which when combined with services that recognise and support parent competencies, and emphasise resilience factors for children, may reduce the need for statutory, and legal, responses:

• Mental illness should be seen as one of a number of adversities that influence the quality of life of many families.

• The health and social care needs of children and parents should be considered jointly.

• A life span perspective that emphasises children’s changing developmental needs over time and recognises the lifelong implications of severe mental illness for all family members. This points to the need for preventative and pro-active interventions that may need to extend beyond crises.

These principles that re-frame how a parent’s, and child’s, needs might be understood and when cases are referred to the Children’s Court, and they involve parental illness, the legal decision-makers have a context in which to decide present an future outcomes for children. Campbell (1999) emphasised that the best place for solving problems is the community where they occur, and where services will work together there is a better chance that problems can be solved this way, leaving only those problems that cannot be resolved for statutory attention.

The Victorian service system has recognised the importance of community-based and multi-disciplinary services and put in place a range of services (for example, the Parent Project, Maroondah Adult Mental Health Service, the Mothers Support Programme, Prahan Mission, Keeping Kidz in Mind, Hidden Children Hard Words MHRI, 1997), that focus on prevention and early intervention to help parents cope with mental illness and its impact upon them and other family members. Child and adolescent and adult mental health services, the child protection service, maternal and child health nurses would also see many of this client group, So too do drug and alcohol services, youth and family services, schools, medical practitioners, and the juvenile justice system. Other initiatives also provide a range of approaches for service cooperation: outposting mental health workers in child protection teams, introducing case review processes to review clients who may require multiple service responses; providing mental health consultation to child protection staff. All provide professionals with the opportunity to develop informal networks that encourage consultation and the exchange of information between mental health and child welfare workers.

CONCLUDING COMMENT

These issues will not receive priority unless attention is paid to the following pivotal issues. First, knowledge of the risks for emotionally abused or stressed children must be shared between all services and providers. Second, adult mental health services must put more emphasis on the parenting responsibilities of their clients with dependent children and have stronger links with family support and child welfare services. Third, mental health must be accepted as everybody’s business although there must also be a realistic acknowledgement of the opportunity and restraints on all. A shared systems interactional “mental model” will see the whole complex picture where multiple needs need to be addressed through “joined up” services. These changes must be driven by social polices that are not just welfare and health based, but include attention to child welfare legislation (Sheehan, Birleson, and Bawden 2001). The development of inter-agency cooperation and inter-professional confidence is essential if families are to receive the support they need, and if the legal system is to have confidence that the best interests of children and vulnerable families are properly met.

Ayre P (1998) “Significant Harm: Making Professional Judgements” Child Abuse Review, Vol. 7, pp. 330-342.

Buist A “Mentally Ill Families: When are Children Safe” Australian Family Physician Vol. 27, No. 4 pp. 261-265.

Campbell L (1999) “Collaboration: Building inter-agency Networks for Practice Partnerships” in Cowling V. (ed.) (1999) Children of Parents with Mental Illness, Australian Council for Educational Research, Melbourne, Victoria.

Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (2000) National Action Plan for

Promotion, Prevention and Early Intervention for Mental Health 2000, Canberra ACT.

Department of Justice, Victoria Statistics of the Children’s Court of Victoria, 1998/9, 55 St Andrews Place, Victoria.

Dingwall R, Eckelaar JM and Murray T (1983) The Protection of Children: State Intervention and Family Life, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1983.

Falkov A (1997) “Adult Psychiatry–A Missing Link in the Child Protection Network: A Response to Reder and Duncan,” Child Abuse Review, Vol. 6, pp. 40-45.

Falkov A (ed) (1999) Crossing Bridges: Training resources for working with mentally ill parents and their children, Department of Health, HMSO, London.

Glaser D and Prior V (1997) “Is the Term Child Protection Applicable to Emotional Abuse” Child Abuse Review, Vol. 6, pp. 315-329.

Glaser D “Defining and Identifying Emotional Harm, Assessment and Notification” Keynote Paper, Working Together for Children at Risk Conference, Monash University, Melbourne, 18-19 November, 1999.

Glaser D and Prior V (1997) “Is the Term Child Protection Applicable to Emotional Abuse” Child Abuse Review, Vol. 6, pp. 315-329.

Hallett C (1993) Inter-agency Work on Child Protection and Parental and Child Involvement in Decision Making in NSW Child Protection Council Seminar Series No. 1, NSW Government Printer.

Hallett C (1995) Interagency Coordination in Child Protection, Studies in Child Protection, HMSO, London.

Hetherington R, Cooper A, Smith P and Welford G (1997) Protecting Children: Message from Europe, Russell House Publishing, Lyme Regis, UK.

Hetherington R, Baistow K and Johanson P (1999) Executive Summary of the Interim Report to the European Commission, May 1999, The Icarus Project, Centre for Comparative Social work Studies, Brunel University, Middlesex.

Hetherington R, Baistow K, Johanson P and Mesie J (2000) Professional Interventions with Mentally Ill Parents and their Children: Building a European Model, Centre for Comparative Social Work Studies, Brunel University, Middlesex.

Holt R, Grundon J, and Paxton R (1998) “Specialist Assessment in Child Protection Proceedings: Problems and Possible Solutions” Child Abuse Review, Vol. 7, pp. 266-279.

Human Services Victoria, Victoria’s Mental Health and Protective Services Working Together: A Guide for Protective Services and Mental Health Staff, February, 1998.

Hunt J and McLeod A (1997) The Last Resort: Child Protection The Courts and the 1989 Children Act 1989, Centre for Socio-legal Studies University of Bristol.

Iddamalogda K and Naish J “Nobody cares about me: Unmet needs among children in West Lambeth whose parents are mentally ill” cited in The needs of children of parents with a mental health problem, (1999) Lanarkshire Health Board, England.

Offord DR, Kraemer AE, Kazdin AE, Jenson PS, and Harrington R (1998) Lowering the Burden of Suffering from Child Psychiatric Disorder: Trade-offs among Clinical, Targeted and Universal Interventions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37: 686-694.

Pietsch J and Cuff R (1995) Hidden Children: Families Caught Between Two Systems. CHAMP Report: Developing Programs for Dependent Children who have a Parent with a Serious Mental Illness. Melbourne: Mental Health Research Institute of Victoria.

Reder P and Duncan S (1997) “Adult Psychiatry–A Missing Link in the Child Protection Network” Child Abuse Review Vol. 6, pp. 35-40.

Rutter M and Quinton D (1984) Parental Psychiatric Disorder: Effects on Children. Psychological Medicine 40: 1257-1265.

Sheehan R (1997) “Mental health issues in child protection cases” Children Australia Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 13-21.

Sheehan R (2001) Magistrates’ Decision-Making in Matters of Child Protection, Ashgate, Aldershot, Hants., U.K.

Sheehan R (2000) “Family preservation and child protection: The reality of Children’s Court decision-making” Australian Social Work, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 41-46.

Sheehan R, Pead-Erbrederis C. and McLoughlin A (2000) The Icarus Project: A Study of Professional Interventions with Mentally Ill Parents and their Children; The Australian Contribution, Dept. of Social Work, Monash University, Melbourne, January 2000.

Sheehan R, Birleson P and Bawden G (2001) “Working Together for Children at Risk” Report on the Conference held at Monash University, Victoria, Australia, 18-19 November, 1999, Children Australia, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 33-37.

Stanley N and Penhale B (1999) “The Mental Health Problems of Mothers Experiencing the Child Protection System: Identifying Needs and Appropriate Responses” Child Abuse Review, Vol. 8, pp. 34-45.

Stevenson O (1996) “Emotional Abuse and Neglect” in Child and Family Social Work, No. 1, pp. 13-18.

Rosemary Sheehan is affiliated with the Social Work Department, Monash University, Caufield, 3145, Victoria, Australia (E-mail: [email protected]).

Presented at the 3rd International Conference on Social Work in Health and Mental Health, July 1-5, Tampere, Finland.

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “Partnership in Mental Health and Child Welfare: Social Work Responses to Children Living with Parental Mental Illness.” Sheehan, Rosemary. Co-published simultaneously in Social Work in Health Care (The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 39, No. 3/4, 2004, pp. 309-324; and: Social Work Visions from Around the Globe: Citizens, Methods, and Approaches (ed: Anna Metteri et al.) The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc., 2004, pp. 309-324. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address: [email protected]].