6. Investors and the Power of Markets

The preceding chapter outlined a framework and set of principles and practices that an organization, particularly a public corporation, can use to effectively manage its ES&G issues and activities. This chapter suggests that implementing this approach, while entailing considerable effort, can be justified. It has been shown to be effective, and it creates the conditions required for the firm to create new financial value. More specifically, I delve into the workings of our capital markets, and I develop and explore one of the major themes of this book: capital markets are reshaping how companies are approaching sustainability. They will drive corporate America toward a more sustainable future, whether or not it is ready to go there. To further support this argument, and particularly for your benefit if you remain unconvinced of the value proposition presented by sustainable business practices, Chapter 7 reviews the established empirical evidence that addresses this issue.

This chapter explores in depth why investors might have an interest in corporate sustainability behavior. It also looks at whether financial market actors appear to consider sustainability endpoints and, if so, how and to what degree. This chapter also explores how market forces appear to be shaping interest in and the practice of corporate sustainability activities. I will show that financial community actors are playing a substantial and growing role. I also will offer some suggestions for appropriate responses on the part of those working in and for companies on sustainability issues.

To begin, I will review some basic information about the financial markets, including their size and prominence, and the primary interests of market participants, focusing on those who play the most pivotal role—investors. This perspective is supplemented by a brief discussion of the evidence that suggests that financial market actors are paying increasing attention to corporate sustainability issues. (This discussion is expanded on in Chapter 7.) I will then examine some of the important requirements and constraints that apply to professional investors and to companies that offer financial securities to investors. This discussion takes place at both a general level and, more specifically, with regard to ES&G considerations. With this foundation, I then describe some of the major evaluation methods investors use. This discussion is followed by a delineation of the major information providers and other intermediaries that serve investors. I also review some important recent developments and major trends that may influence the behavior of both companies and investors with regard to ES&G issues during the next few years. The chapter closes with a summary and discussion of the implications of financial market involvement for those working on sustainability practices both within and outside of the firm.

Market Theory and Underlying Assumptions

For our purposes, I define markets as venues in which buyers and sellers of defined commodities can conduct transactions (purchases and sales) in which there is a high degree of certainty that all parties will honor the agreed-upon terms. Participating sellers using markets receive continual feedback on which products and services are of interest to others, what terms and price(s) are acceptable to buyers, and other information that is crucial to making sound decisions about what to produce and offer for sale, when and where, and under what terms. By participating in markets, buyers receive access to goods and services that they might not otherwise be able to obtain or make/perform. They also can make informed decisions about what to produce internally and what to procure from outside the organization. Indeed, it is widely accepted that well-functioning, competitive markets generally offer the greatest array of products and services at the lowest prices. It is also accepted that the “unseen hand” of the marketplace induces producers to deliver the goods and services consumers want in the appropriate quantities. It also creates “consumer surplus” that increases societal well-being and, over time, leads to the most efficient allocation of investment capital.

These points are elementary and well-known (at least intuitively) to most people. What is less well-understood and often forgotten is that the generally accepted theory of how markets can and do work is based on a number of important assumptions. If these assumptions are violated, it becomes far less clear that markets, even “free” markets, will deliver what their advocates promise.1 In the current context, the more important of these assumptions include the following:

• The market is fully competitive (no monopoly sellers or buyers).

• All participants have perfect information (about prices, availability, product/service features, and so on).

• There are no transaction costs.

• All participants maximize their personal utility (and, presumably, that of their organizations).

If examined closely, each of these assumptions is of dubious validity—at least under conditions that are quite common in a large and diversified economy such as that in the U.S. Competitiveness varies greatly among industries, in some cases because of structural factors and in others as a function of industry maturity. It is widely known that certain types of activities, particularly those that have significant economies of scale, tend to become natural monopolies (or their close cousin, oligopolies). This is why, to promote economic efficiency and societal welfare, we have regulated monopolies to provide such basic goods and services as electric power, natural gas, and other utilities in many parts of the country. Monopolies also can take shape on their own over time. As an industry matures and competitive forces produce stronger and weaker firms and, in turn, growing consolidation (the stronger overcoming [and often buying] the weaker), a smaller number of companies have increasing market power. Recognizing the adverse impacts of increasing industry concentration on consumer choice and prices and more generally on social well-being, U.S. lawmakers enacted federal antitrust laws nearly 100 years ago. This happened precisely because markets cannot be relied on to continuously produce full, open, and fair competition among all participants. There may be a diversity of views on whether U.S. antitrust laws have been enforced adequately or are fully effective. However, I believe that there can be little doubt that they have provided a useful control mechanism for curbing egregious, self-serving corporate behavior and limiting volatility in the supply and price of many goods and services.

It may seem a bit odd to contemplate the availability of information in 2011, more than a decade into the Internet age, when it seems that information is all around us. Nonetheless, it is worthwhile to consider how much of what we see and hear through the Internet and various other media channels is truly useful. In the context of participating in one or more markets, information asymmetry has always existed between and among various buyers, sellers, and intermediaries. Moreover, I believe that most people understand and are comfortable with the fact that some people and organizations work harder and more skillfully to develop facts and insights than others. These attributes allow them to engage in commerce more successfully. In fact, the ability to benefit from one’s own diligence and talents is a major component of our “cultural DNA.” The results of these diverse efforts demonstrate that not all relevant information is instantly available to all market participants, and this evidence is all around us. Indeed, you need look no further than the countless commercial databases, industry-specific publications, membership organizations, books (such as this one), and training courses and seminars available online, in print, and in person. These and other offerings enable the purchaser to obtain insights that he or she did not possess previously and either could not develop independently or could not obtain cost-effectively (make/buy considerations). Many billions of dollars change hands in this country every year to try to correct existing information asymmetries and gain competitive advantage. If anything, such activity is increasing rather than diminishing as information technology advances. Later in this chapter I will return to this topic as it applies to ES&G management and investing.

Given the foregoing, the notion that market transactions are costless seems particularly unrealistic. Yet it is commonly accepted by many people, at least informally. Many transactions between buyers and sellers do not have any definable fees or explicit costs. But in other cases (including purchases of many securities), selling or, more commonly, buying through an intermediary involves a payment or markup. If we then consider the indirect costs of participating in a transaction, such as, purchasing information, time spent performing research/evaluation, travel, shipping, and taxes, it becomes clear that the “friction” surrounding many sales and purchases of goods and services in our economy is not zero. In fact, it may be quite significant.

Finally, one of the cornerstones of market theory is the idea that people are rational and always act to maximize their personal utility. A commonly stated and important corollary is that personal utility means wealth. In other words, people continuously seek greater wealth. In terms of our discussion here, another important implication is that people working in organizations also are rational, informed, utility-maximizing agents who in all cases make optimal decisions to benefit (increase the wealth of) their employer. As noted in Chapter 2, this book doesn’t have enough space to discuss all the flaws in and counter-examples to these related theories of human behavior.

In the context of this chapter, what is most relevant is the notion that people always (or at least routinely) make rational decisions that are in the best interests of their organization. Until the last 15 years or so, this idea had been accepted (indeed, embedded) widely and deeply in the business community. So ingrained was this belief that it was difficult to even have a conversation about advanced ES&G practices with certain constituencies, or to induce public sector entities to entertain the possibility that they could be doing more to promote sustainable business behavior. The emergence of the field of behavioral economics has illuminated the factors that really drive human thinking, decision-making, and behavior. Even so, deep skepticism remains in some quarters that any intervention into the workings of markets or individual companies to promote sustainability or other desirable practices is either necessary or desirable. Such skeptics still voice concerns about whether, for example, an array of public sector programs and partnerships are necessary. They seem unconvinced that these programs produce any significant net benefits and are worthy of support.2 This is true despite the success of initiatives such as the myriad voluntary pollution-prevention programs operated at the state level and the federal Energy Star program, which addresses the energy efficiency of a variety of building types, building components, appliances, electronics, and other goods. These diverse programs share at least one common feature: they provide information and, often, tools and other assistance to companies to help them make environmental and/or health and safety performance improvements in a cost-effective manner. That is, they help produce win-win outcomes by reducing energy use, pollutant emissions, waste, unsafe working conditions, and/or other undesirable aspects in a way that saves money, net of investment cost. They do so by creating open access3 (no competitive barriers), overcoming information asymmetry, reducing transaction costs, and demonstrating, in tangible ways, that the partnering organization may not presently be maximizing its utility. In other words, these programs have proven that there actually are lots of “$20 dollar bills lying on the sidewalk” waiting to be picked up.

Although some of this discussion may seem a bit esoteric, it provides an important foundation for the treatment of capital market (and corporate) behavior that is presented later in this chapter.

Capital Markets

Among the many types of markets that exist in the U.S. and around the world, perhaps the most influential in many respects are the capital markets. Individual entities within the capital markets provide a wide array of financial products, including company equity and debt securities (stocks and bonds, respectively), loans, notes, and insurance policies. Those that are most relevant to the current context are those used by companies to raise capital, either by selling portions of company ownership (stocks) or by issuing tradeable promises to repay invested capital at a specified future time, along with periodic interest payments in the interim (bonds). Because these securities can be traded on organized markets (security exchanges), they can be purchased by and delivered to the buyer quickly at a clear price. They also are highly “liquid,” meaning that an investor can (generally) sell them quickly and receive the sale proceeds without undue delay. These features have helped the financial markets attract investment capital from far and wide, greatly increasing the pool of financial resources available to firms seeking to grow. The continual and often rapid growth of companies using this invested capital has, in turn, greatly accelerated gains in general economic activity and the standard of living in countries with well-functioning financial markets.

Markets for financial securities (such as stocks, bonds, and options) are highly developed and efficient in the U.S. and in many other economically advanced countries. Generally, these securities are traded on exchanges that establish rules concerning how trades are to be made and executed, and they provide guarantees that the promises made by buyer and seller are fulfilled.4 At this point in time, and enabled by the great advances in information technology that have occurred during the past 20 years (including growth of the Internet), it is fair to say that, at any time, one or more stock markets are open and operating somewhere. The importance of international investors to sustainability thinking and practice is discussed later in this chapter.

Companies that participate in these markets compete with one another, offering their bonds or stock as one investment option available among thousands. To be successful in this competitive environment, they must be able to demonstrate a sound business model and “financials” warranting the trust of the investing public.5 Both debt and equity investors are looking for value. Debt, or fixed income, investors obtain value by receiving a predetermined income stream (typically a fixed percentage of the stated value of the debt security) in exchange for a given and generally well-characterized level of risk.6 Equity investors receive no assurance of a positive return on investment but also face no limit on its upside potential. Importantly, under both investment scenarios, it is incumbent upon companies to demonstrate the efficacy and worth of their business models (including ES&G activities and programs, if any) to their investors. Sustainability improvements, just as with any other investment of the firm’s capital, must contribute, if even in an indirect way, to revenue growth, improved profitability, and/or risk reduction. As discussed next, the practice of sustainability investing involves determining the financial value that each firm’s ES&G activities creates (or destroys) and evaluating this net impact along with many other criteria of various kinds.

Who Investors Are and What They Care About

Those who have worked in the environmental, health and safety, and/or sustainability field for any length of time have doubtless heard (and perhaps stated) the proposition that discretionary ES&G initiatives or programs within an organization “add value.” Commonly, value is not defined formally, but it may include such perceived benefits as greater efficiency, improved safety, a more highly skilled and motivated workforce, lower emissions, and the like. I believe that it is appropriate to both consider and seek to obtain such benefits through improved ES&G management practices, as discussed in depth in Chapter 5.

It is vital to understand, however, that such benefits do not comprise “value” to an investor. Instead, value is created through one or more of three distinct means, as illustrated in the following sidebar. This chapter identifies the major types of investors in corporate and other securities and describes how these securities differ from one another. First, however, I review a few fundamentals about how investors think and behave. This foundation is integral to an understanding of whether and under what circumstances an investor might show an interest in ES&G management practices and performance.

Investing is about making money and intrinsically involves making a prediction about the future. No rational investor buys an equity security unless he or she expects that it will be worth more in the future, or unless it yields a stream of dividends that are adequate to offset the absence of a share price increase. Assuming that the market for such securities is efficient and that all relevant information is available to motivated market participants, the market price today reflects the consensus judgment of all buyers and sellers as to any given security’s true worth. Similarly, a rational purchaser of a bond expects that the yield (periodic payments) he or she receives is adequate to compensate for the lack of access to his or her capital for the holding period and to offset the risk of default by the bond issuer. Yield is determined by a bond rating, with riskier securities requiring a higher yield (interest rate) than less-risky securities. Bonds can either be held to maturity, when the original investment amount is repaid, or sold through an exchange on the secondary market, much like a stock. Because most bonds are issued with a fixed yield, changes in interest rates (or riskiness of the issuing entity) induce changes in the bond’s market price. Again, a bond’s market price reflects what the market overall believes is an accurate value, based on the current interest rate climate, company position, and perceived trends.

This means that any information on corporate ES&G posture, activities, and/or performance must tell the investor something about the future. Information on past performance is of interest only to the extent that it helps the investor make an informed judgment about the company’s future. More specifically, such information must be relevant to the prediction of the firm’s future revenues, earnings, cash flow,7 or risk. The extent to which conventional ES&G data responds to these needs is discussed in depth in a subsequent chapter.

Professional investors evaluate these major financial endpoints at several levels.8 First, they generally decide how to invest their capital among the different available asset classes. These include cash and very short-term investments, fixed income (bonds), stocks, options, commodities, and even real estate. Because we are primarily interested in corporate behavior here, I will focus on stocks and bonds. The investor then filters his or her investment choices for whatever capital is to be invested in stocks and bonds by assessing which economic sectors appear to offer the most favorable characteristics. This choice is based on such factors as the current stage of the economic cycle, the interest rate environment, and other macroeconomic characteristics. Finally, within the sectors chosen for investment, the focus turns to individual companies.

Investors maintain a diversified portfolio. That is, they don’t hold a few securities at a time, but rather dozens to hundreds. This is because, as demonstrated by both investment theory and empirical evidence, adding securities to an investment portfolio, at least to a certain point, reduces volatility in returns (risk) without adversely affecting its expected overall return. As discussed further later, the principle of diversification is so widely accepted that it has been adopted as a component of securities law across the U.S.

As discussed previously, investors, even individual investors, often diversify across asset classes. These classes can range from those that pose little or no risk (U.S. government securities) to those that pose minimal to moderate risk (corporate bonds, from “investment grade” to “junk”) to stocks and, finally (in some cases), futures and options. Assuming that markets are working efficiently and assets are not mis-priced, in every case, and for every component of the portfolio, there is a direct relationship between the risk it poses and the potential reward it offers. In other words, the higher the risk, the higher the potential reward, and vice versa. So government bonds pose little or no risk but also do not offer a high potential payoff. Stocks pose a substantial risk, up to and including the loss of your entire investment, but they also offer an unlimited upside that is difficult to replicate using less-risky investment options.

In the context of relating ES&G issues to investing, a key point to consider is how a sector, industry, or company’s ES&G posture and trends may affect future revenues, earnings, and risk to either the organization itself or future cash flows. Another point to consider is whether the current valuation fully and accurately accounts for all important facts, including ES&G issues. Additional returns (above what can be obtained through investing in broad indexes) may be generated by identifying sources of hidden value and investing aggressively in the firms positioned to capture it. Returns also may be generated by identifying underappreciated sources of risk to future returns that result in securities that are currently overvalued. In the latter case, the investor can both divest any securities owned and invest more aggressively by “shorting” the relevant stock(s).9

As you will see shortly, a substantial and growing segment of the investor community is examining specifically how ES&G issues and criteria can help them identify such opportunities to outperform both their competitors and standard investment industry benchmarks.

Size and Composition of U.S. Capital Markets

Notwithstanding the vast trade imbalances and budget deficits of recent years, the U.S. is still by a wide margin the world’s largest capital market. As shown in Table 6-1, as of 2006, the total value of U.S. financial assets was substantially greater than that of the next-largest economy (the Euro Zone). In fact, the U.S. was comparable in size to the Euro Zone and its next-largest competitor (Japan) combined. In recent years, the picture has changed markedly due to the near-collapse of the global financial system in 2008–2009 and significant funds flows, particularly between the U.S. and China. But most of the basic relationships shown in Table 6-1 still hold. Of particular relevance here are the size and prominence of the U.S. markets for equity and private (corporate) debt securities. Quite simply, the U.S. is and is likely to remain the world’s dominant investment market for stocks and bonds for some time.

Table 6-1. Global Financial Assets by Region for 2006 (in Trillions of Dollars)

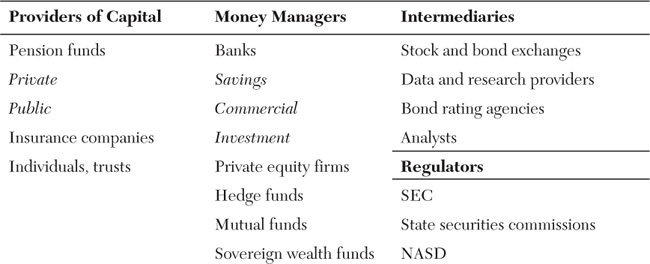

To purchase these debt and equity securities, money managers collect financial capital from a wide array of sources, including public and private (corporate) pension funds, insurance companies, and individuals and trusts. Firms that collect, deploy, and manage this invested capital include commercial and investment banks, private equity firms, hedge funds, and mutual fund companies. A number of intermediary and supporting organizations also play important roles in supporting the functioning of our financial markets. These include the following:

• Stock, bond, and commodity exchanges, on which securities are traded

• Numerous data and research providers, who support investment analysis and decision making by providing crucial data, projections, and other information and tools

• Bond rating agencies, which evaluate the business prospects and risks of organizations issuing debt securities

• Analysts, who evaluate securities and their issuers—some from the standpoint of the issuing companies (“sell side”), and some from the point of view of the prospective investor in the securities (“buy side”)

Finally, several types of organizations play important regulatory roles in ensuring that our capital markets function effectively, efficiently, and transparently. These include the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission at the federal level; state-level securities commissions that exist in every U.S. state; and several voluntary, self-regulatory bodies representing some of the market participants, the most prominent of which is the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD). Table 6-2 summarizes the major types of entities involved in the capital markets and their respective roles.

Table 6-2. Major Capital Market Participants and Their Roles

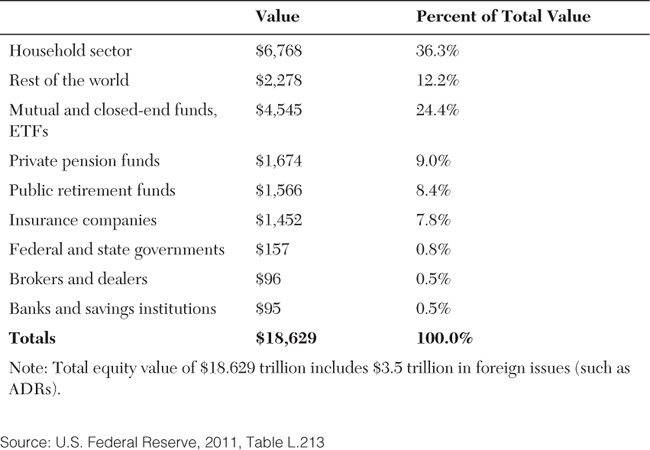

Most of the empirical work linking ES&G improvements and financial value is focused on equities (stocks). In fact, most of the current activity in the ES&G investing space is focused on equity securities. Table 6-3 shows the value and ownership of the U.S. equity market as of mid-2010.

Table 6-3. Value (in Billions of Dollars) and Ownership of U.S. Equity Securities

This table shows that despite the strong recovery of U.S. (and other) equity markets since mid-2009, the total value of U.S. equities still has not reached even 2006 levels, much less the precrash peak of $25.6 trillion observed in 2007. U.S. households directly own about 36 percent of U.S. shares (by value), and mutual and closed-end funds own nearly one-quarter. Together, private and public pension and retirement funds own more than 17 percent, and insurance companies account for an additional 8 percent or so. Governments, brokers and dealers, and banks together account for less than 2 percent of the total. Interestingly, nearly $2.3 trillion in U.S. equity securities, or 12 percent of the total, is owned by investors outside the U.S. Notwithstanding the fiscal and economic difficulties faced by our country, particularly in the long term, the U.S. remains a popular and highly regarded place in which to invest.

Disclosure

As discussed previously, investing in equity or fixed income securities involves finding sources of value through collecting and evaluating relevant information on particular firms’ businesses, capabilities, future prospects, and ability to perform at or beyond anticipated levels. To make such determinations, investors require information, which in many cases can be provided only by the company issuing the securities itself.

Required Disclosure

Because the disclosure of financial and certain operating information is so critical, as a matter of public policy the U.S. and most other advanced economies have established requirements that mandate regular disclosure by all firms that have issued either equity or debt securities that are sold to the investing public. U.S. companies fitting this description are subject to regulations established by the SEC.10 These regulations stipulate that such companies issue every quarter a 10-Q report, as well as an annual report and accompanying 10-K report following the close of each company fiscal year. These documents must include three basic financial statements: the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement. The balance sheet is focused on “stock” measures, and the other two statements are focused on “flow” measures.

Fundamentally, the balance sheet is an end-of-period snapshot. It lists and quantifies what the company owns and what it owes. It provides financial values for the various pieces of the business. This includes both liquid (short-term) assets such as cash on hand, accounts receivable, and inventory, and long-term assets such as land and plant and equipment. On the other side of the balance sheet are listed the firm’s liabilities (what it owes), again subdivided by short- and long-term obligations. Accounts payable, interest owed, and the like are listed here. The difference between the total value of assets and the total value of liabilities is equal, by definition, to the value of shareholders’ equity, or the net value of the business. Healthy businesses have substantial positive net equity. The balance sheet incorporates many assumptions and conventions that have been developed within the accounting profession over the years and commonly includes many explanatory notes. Review and analysis of these notes is a key activity in investment analysis.

The balance sheet also is where any ES&G liabilities are supposed to be identified and quantified. These generally are listed in the Long-Term Debt and Other Obligations category (with the exception of the current portion, if any) and are explained in notes. Such obligations may include responsibility for cleanup of contaminated sites and other liabilities that can be reasonably quantified. As discussed in Chapter 7, however, such liabilities have been chronically under-reported by U.S. companies to this point. To address this problem, several years ago the standards organization of the public accounting profession issued guidance. It made clear that firms were required to analyze and report their contingent liabilities from retired assets (such as idled, potentially contaminated plants and sites) using specified methods. Although it is still early in the process, it does not appear that disclosure of such liabilities in financial statements has increased markedly. I discuss this issue in more depth later.

The income statement quantitatively describes the firm’s activities from an economic perspective. It addresses, in order, revenues (sales), the costs of producing these revenues (labor, materials), the more general costs of operating the firm, and the difference between revenues and costs, which is income (earnings) or loss. Finally, any earnings may be distributed in various ways, including in the form of payments to shareholders through dividends. In contrast with the balance sheet, the income statement considers the period (year or quarter) as a whole. It also commonly includes many explanatory notes.

In similar fashion, the cash flow statement describes the firm’s activities in terms of their cash impacts on the business. These activities are organized into the following categories: Operating activities (conducting the firm’s main business[es]); investment activities, such as purchasing new land, equipment, or other firms; and financing activities, including securing the funds needed to operate the firm, such as through obtaining bank loans or issuing bonds or stock. The cash flow statement collects and tallies all these sources and uses of cash into and out of the firm and again considers the period as a whole.

On a yearly basis, the 10-K versions of these financial statements are incorporated into the firm’s annual report, which also must include a written management discussion and analysis (MD&A). The MD&A often includes crucial information about and insight into the company’s recent experience, future plans, significant challenges, and likely responses. Company senior management is expected to acknowledge and adequately discuss any and all issues that may exert a significant influence (positive or negative) on the firm’s future performance. This includes ES&G issues. Unfortunately, however, again this is an area of relatively clear regulatory coverage that historically has been widely downplayed or ignored.

Together, the three financial statements, along with the annual report, provide much of the key information investors require to make informed decisions about a particular company’s existing businesses, ability to compete successfully and accomplish stated goals and commitments, and prospects for the future. As you will see a bit later, the adequacy of this information to satisfy the needs of all investors, particularly those focused on or interested in ES&G issues, is far from clear. This fact has had several important implications.

Despite clear signs that there were gaps in the coverage and/or enforcement of existing SEC disclosure rules, the requirements just described provided the basic road map for developing and reporting corporate financial information for many decades. Generally, it appeared that most investors were satisfied with the types and depth of information they were provided at quarterly intervals, although some financial institutions were not. These money management firms leveraged their relationships with the senior management of certain publicly traded firms to obtain information that had not been publicly disclosed to that point. In exchange, some touted the shares of these companies over those of competing firms, or otherwise used this information to further their own interests and/or those of their clients.

These and many other abuses came to light about ten years ago in a series of major scandals and the spectacular failures of several previously high-flying firms such as, Enron, WorldCom, Adelphia, Tyco International, and Global Crossing. In the wake of these scandals, the resulting billions of dollars in losses to investors, and the ensuing recession, the U.S. Congress enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (Public Law 107—204). Sarbanes-Oxley, or “Sarbox,” contains three major requirements: disclosure controls and procedures, internal control over financial reporting, and Officers’ certifications of controls. More specifically, Sarbox and implementing regulations require independence of auditors and the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors and effective oversight of the auditing function by the Committee, which must include a financial expert. In addition, to comply with the certification requirement, the company Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and Chief Financial Officer (CFO) must sign a statement of responsibility. In this statement they claim ownership of the completeness and effectiveness of the firm’s internal financial information systems and controls, as well as the accuracy and completeness of its regular (quarterly) financial reports. Notably, Sarbox does not apply to privately held firms. Its purpose is expressly to protect public investors from fraudulent and abusive behavior and to promote effective corporate governance in publicly traded firms. The actual costs and benefits of Sarbox are still being debated, but its enactment has brought a greater focus to information integrity and a better understanding of risks to the firm.

Certain other SEC rules11 also apply to ES&G issues, particularly those concerning impacts on the environment and their consequences. Core SEC requirements include a complete “Description of the Business,” discussion of any legal proceedings (such as for permit violations), and, in the required MD&A, delineation of any risks or opportunities that might be material to the firm’s future prospects. Such risks include contingent liabilities such as possible future contaminated site cleanup responsibilities. Existing SEC rules cover three substantive areas: accrual of liabilities in financial statements, disclosure of these liabilities in financial statement footnotes and SEC filings, and estimations for both accruals and disclosures. Many of these rules apply only to matters that are “material” to the company’s financial condition. Generally, a matter is understood to be material if a prudent investor would reasonably want to know about it. That said, the SEC has consistently declined to define materiality, preferring instead to rely on established case law when and where necessary. As I will demonstrate in the next chapter, in a number of clearly documented instances, one or more ES&G issues have risen to the level at which any rational investor would want to know about them, yet the required disclosure was not made.

Recognizing this problem (or at least some aspects of it), the organization representing the financial accounting profession in the U.S., the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), issued a standard in 2002. It was followed by a more definitive Financial Interpretive Note (FAS 143/FIN 47) that related specifically to environmentally impaired assets and systems. FAS 143/FIN 47 explicitly rejected the generally accepted (and vague) preexisting estimation scheme and replaced it with a mandated approach consisting of a probabilistic analysis of future liability. In other words, it is no longer acceptable to, in effect, throw up your hands and say that there are too many uncertainties to estimate a liability. Rather, the owner of a contaminated property must now use quantitative analysis (such as Monte Carlo simulation modeling) to generate and evaluate probability distributions of the different possible outcomes and generate an expected value of the property’s future liability. This may sound somewhat esoteric, but the net effect of this significant policy shift is to pull liability recognition forward. This may have major income statement and balance sheet implications for affected firms (Smith, 2005).

Not all corporations have contaminated property from legacy operations that is affected by these emerging requirements. Nevertheless, this issue provides a tangible example of how ES&G issues can affect a company’s financial strength and capability and pose financial liabilities that may not be fully recognized or monetized. It also is emblematic of the types of concerns that have prompted interested investors to seek additional disclosure requirements addressing ES&G issues and concerns.

Indeed, pressure from certain portions of the investor community has resulted in several recent steps by the SEC. These measures are intended to compel corporate senior executives to be more forthcoming about how they are addressing ES&G issues and/or to take steps to improve their own structure and performance, particularly in the area of governance. Recent SEC activities include ongoing coordination with the EPA to review and assess conformance with existing SEC disclosure regulations, and the formation of a study group to evaluate whether ES&G disclosure should be made mandatory, as well as formal regulatory activity. In the latter category, the SEC issued proxy disclosure enhancements in December 2009.12 It issued a memorandum “clarifying” that firms have an existing, affirmative duty to disclose the potential impacts of major environmental issues, specifically global climate change, in February 2010.13 And it issued a final rule providing enhanced access for shareholder nominees in December 2010.14 In addition and, in some ways, most importantly, the SEC is still considering petitions submitted by the U.S. Social Investment Forum (SIF) and the NGO CERES urging the SEC to require mandatory ES&G reporting. It seems clear that the SEC under the current presidential administration is far more focused on shareholder rights and transparency than it was during the preceding eight years. But it remains unclear whether the SEC will ultimately require comprehensive ES&G disclosure, reporting on GHG emissions and related issues only, or neither. Those interested in corporate sustainability from any and all perspectives might want to monitor this issue, because it could be a game-changer.

Voluntary Disclosure

Currently, no U.S. legal requirements compel corporations to disclose their ES&G (or component environmental or health and safety) policies, management practices, or performance. But the SEC recently made clear that it expects companies to carefully evaluate the climate change issue and how it might affect their operations. Nevertheless, a number of current and emerging requirements for public reporting affect at least some companies. More generally, participation in voluntary sustainability reporting initiatives is growing both in the U.S. and internationally.

As discussed in Chapter 3, over the past two decades, the members of several industry and trade organizations have developed codes of conduct and standards for managing ES&G issues. Most of them now include provisions for at least limited reporting of results. An example is the global chemicals industry’s Responsible Care program (ICCA and Responsible Care, 2008). Another example is the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) and the Forest Stewardship Council-US standards that have been adopted throughout much of the U.S. forest products industry (SFI, 2010; FSC-US, 2010).

At a more general level, corporate reporting of ES&G performance has been promoted by a range of organizations during the past 20 years or so. Over time, these efforts have consolidated into a small number of prominent and active programs that are now organized as nonprofits. At the same time, the scope of the issues they address has expanded, at least in some respects, to cover not only environmental issues, but also health and safety, social/equity, and economic issues. That is, they now directly take on the issue of corporate sustainability. The most prominent among these are the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), and the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). Table 6-4 describes major features of these programs and how they compare and contrast.

Table 6-4. Comparison of Major Third-Party Programs Influencing Corporate ES&G Disclosure

The GRI and the UNGC are intended to reflect the interests of society at large. They seek to stimulate the adoption of more comprehensive and aggressive management, tracking, and reporting of company responses to a variety of ES&G issues. Both reflect a heavy emphasis on labor rights and the interests of organized labor generally, but they also speak to a number of important EHS issues. The CDP, in contrast, is fundamentally about investments and investors, although its goals similarly are given effect mainly through the use of principles and/or a reporting template.

The GRI, UNGC, and CDP all are targeted at and seek to directly change the behavior of corporations.15 But nominally they have relevance to and can be adopted by other types of organizations as well.

A key feature of each initiative is required (or strongly suggested) corporate reporting. This reflects a shared belief that more consistent, regular, expansive, and meaningful reporting will accomplish the following:

• Offer an impetus for companies to institute stronger and more effective governance practices

• Improve companies’ ES&G management capabilities and performance

• Provide more convincing assurance to investors and other external stakeholders that the firm is upholding its responsibilities and is effectively managing risks and capitalizing on opportunities

This is true despite the disparate goals of the three initiatives.

These initiatives have been highly influential. A strong correlation exists between the indicators suggested by these programs and the information that is actually reported by companies that disclose ES&G data. A few points illustrate this influence:

• The CDP now represents 534 institutional investors with assets of $64 trillion under management. It solicits disclosure of investment-relevant information concerning the greenhouse gas emissions of 3,700 of the largest companies in the world. As of the most recent full report (2008), the CDP had obtained 2,204 responses covering 82 percent of the Financial Times (FT) 500.

• The GRI has grown from a program of an environmental NGO to a stand-alone international organization based in Amsterdam. As of 2008, its members included 507 SRI investors/analysts, NGOs, companies, labor organizations, academics, consultants, and individuals drawn from 55 countries. Reporting guidelines have been in effect for 12 years and have been revised twice. Reporting organizations have increased steadily, although only about 10 percent of these are U.S. companies or other entities. In 2010, 164 U.S. organizations submitted GRI reports; the worldwide total was 1485.16

• As of mid-2009, the UNGC claimed 8,000 participants, including more than 5,300 businesses in 130 countries around the world. U.S. participants numbered 438 as of early 2011, of which 247 were businesses. Interestingly, the UNGC recently expelled 2,048 of its members (about one-quarter) for failing to meet their periodic public reporting obligations (UNGC, 2011). (This type of rigorous enforcement of commitments is quite rare among voluntary ES&G initiatives and perhaps is a harbinger of things to come.)

A subsequent chapter will explore the suitability of the information generated at the behest of these initiatives to investment analysis and decision making. For now, the important point is that, in combination with SEC requirements and conformance to any industry-specific codes of conduct, the GRI, UNGC, and CDP largely define the information developed and reported by companies that is available for use by investors. The following sections examine what types of information are of interest and how it is used to make investment decisions. But first, here are some “rules of the road.”

Institutional Investors and Fiduciary Duty

Having briefly reviewed the landscape of corporate ES&G disclosure and how it does or might inform investor behavior, I now shift the focus back to the types of review and evaluation that investors and analysts perform. I begin by examining some of the constraints and obligations that guide the behavior of these parties, emphasizing particular issues that have some bearing on corporate ES&G behavior and its implications.

Organizations or individuals that manage money on behalf of others have certain obligations under the law. They are defined as “fiduciaries” and, as such, assume an obligation to act in the best interests of the party or parties they represent. Fiduciary duty exists whenever a client relationship involves special trust, confidence, and/or reliance. Fiduciaries are obligated to exercise the duties of using all available skill, care, and diligence when performing their work, and they must maintain a high standard of honesty and full disclosure with their client(s) at all times. They are precluded from obtaining any personal benefit at a client’s expense. That is, in the discharge of their responsibilities, they must always put the client’s interests above their own.

Fiduciary duty is important in the current context because it is the foundation of securities law in the U.S. and many other countries. For example, pension fund trustees have a fiduciary duty to their members and any other beneficiaries to manage the funds entrusted to them with the utmost care and to invest them prudently using all their available skills and effort.

Professional investor behavior also is heavily influenced by the Modern Prudent Investor Rule, which is a fundamental principle of securities law in all or essentially all U.S. states.17 Under this doctrine, investors must do or observe the following:

• They must deploy the assets with which they have been entrusted as if they were their own.

• They must avoid excessive risk. (As a practical matter, this means developing or maintaining a portfolio rather than a single asset or a small number of assets.)

• They must avoid excessive costs.

• Although there is no duty to maximize returns, investors must implement a rational and appropriate investment strategy.

• The portfolio must be diversified unless doing so would be imprudent.

• Prudence and decisions generally are to be judged at the time of investment.

The clear intent here is to ensure that fiduciaries such as money managers understand and abide by a set of behaviors that ensure that the risks taken in investing client funds are reasonable, given the client’s investment objectives and risk tolerance. At the same time, the absence of detailed guidance or more specific requirements gives the professional investor wide latitude in determining the appropriate range of options to consider for a particular client and in choosing the best course of action.

Unfortunately, over time, some common interpretations emerged and received widespread acceptance to the point where they stood largely unchallenged for many years. One such interpretation was that the duty of loyalty owed to the client implied that the money manager was compelled to attempt to maximize returns. This way of thinking became particularly pronounced during the great “bull run” from 1982 through the bursting of the Internet bubble in 1999 and to some degree since. During this period, many individual and other investors became convinced that making money in stocks and, to a lesser extent, bonds was easy and that the markets had only one overall direction—up. In such an environment, investment risk seemed muted. To many, it appeared that the biggest risk was to get left behind as stock prices climbed inexorably higher.

A related factor was an interpretation of modern portfolio theory that held that because diversification lowered investment risk, more diversification (owning more different stocks in a portfolio) always was to be preferred over less diversification. Those who favored socially responsible investing (SRI), or ES&G investing in its formative stages, therefore were confronted by great skepticism. Critics of SRI contended that the use of nonfinancial criteria (such as, environmental performance) that might restrict the number of companies the investor could consider (the “investable universe”) would pose an unacceptable risk to the diversification of the overall portfolio. SRI advocates were not helped by the fact that many of the early SRI screening and evaluation methods were crude. (They often focused on exclusions according to one or a small number of criteria.) This led to the formation of investment portfolios that did not perform well on a relative basis (in comparison with a relevant market benchmark).

Thus, one of the important factors limiting the growth of ES&G investing has been an entrenched interpretation of fiduciary duty as applied to investing. It suggests that factoring environmental, health and safety, social, or broad economic considerations into investment analysis is misguided, improper, and potentially illegal. This belief has been reinforced by the available interpretations of the U.S. federal statute that governs the management of private (corporate) pension funds—the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Interpretations of ERISA made by the implementing government agency (U.S. Department of Labor) have allowed but not encouraged the use of SRI and similar approaches.18

During the past six years, however, the prevailing views on what types of factors investors can and cannot consider have changed significantly. In 2005, a detailed study of investment law in the U.S. and several other countries with advanced capital markets sponsored by the United Nations Environment Programme–Finance Initiative (UNEP-FI) provided a striking and compelling alternative view of the issue. Because the principal authors of the report were attorneys from U.K.-based law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, the report became known as “the Freshfields Report.” It analyzes the evolution of investment law from the standpoint of whether and under what circumstances matters such as environmental, social, and governance considerations may be evaluated by financial fiduciaries as they carry out their duties to responsibly manage their clients’ assets. This document broke some significant new ground and provided the following major conclusions:

• Contrary to conventional wisdom, not only is it acceptable for fiduciaries to consider environmental, social, and governance issues, such issues must be considered when and where they are relevant to any aspect of investment strategy.

• Investment law in the U.S. and most other jurisdictions examined presents no barriers to integrating ES&G considerations into investment fund management activities, so long as the focus remains on the fund beneficiaries and the fund’s purposes (UNEP-FI, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, 2005).

As described next, this report and its conclusions have induced a sea change in how ES&G issues are perceived and managed by both SRI investors and, increasingly, money managers and analysts in some of the world’s largest mainstream financial institutions.

Recognizing these trends, and in the interests of providing more detailed guidance for institutional investors and others who want to incorporate ES&G considerations into their business models, UNEP-FI commissioned an update of the Freshfields Report. It was published in 2009. This study confirmed the findings of its predecessor and also reached a number of profound and wide-ranging conclusions, among them the following:

• Fiduciaries have a duty to consider more actively the adoption of responsible investment strategies.

• Fiduciaries must recognize that integrating ES&G issues into investment and ownership processes is part of responsible investment and is necessary when managing risk and evaluating opportunities for long-term investment.

• Fiduciaries will increasingly come to understand the materiality of ES&G issues and the systemic risk they pose, as well as the profound long-term costs of unsustainable development and its impacts on the long-term value of their investment portfolios (UNEP-FI, 2009).

Accordingly, the nature of the debate has swung from whether considering ES&G factors in investment decision-making is permissible or appropriate to how best to integrate these factors into the data collection, analysis, and investment process. What is particularly noteworthy is the implication that money managers who do not address ES&G issues may become increasingly vulnerable to charges that they have been negligent for not considering reasonably foreseeable risks that may have an adverse effect on the value of their clients’ portfolios. It is probably fair to say that more than a few financial market players remain either uninformed of or unconvinced by the findings of these two reports. Nevertheless, many indicators from the markets show that their impact has been widespread and profound.

In the future, if one or more key actions by U.S. federal agencies were to be taken accepting the reasoning presented in the UNEP-FI analyses, wholesale adoption of ES&G investing in U.S. capital markets could occur quickly. One such action would be a supportive interpretation of ERISA by the U.S. Department of Labor. Another would be action(s) taken by the SEC to either require or strongly encourage regular ES&G reporting by publicly traded corporations. If either were to happen, the sea change that I (and a number of others) have observed beginning to form during the past five years could become a tidal wave.

Traditional and Emerging Security Evaluation Methods

This section briefly profiles some of the major principles and methods that have been applied to professional investing over the past several decades. The purpose here is not to train you to become an investor (or a more successful one), but instead to lay the groundwork needed to illustrate how ES&G issues are relevant to the concerns of investors. Investment theory and practice are complex and the subject of lengthy textbooks, programs of graduate and postgraduate study, and vigorous debate. I have a healthy respect for the knowledge and talents of those involved in the capital markets. Here I simply want to raise awareness of the common interests of investors and other financial market actors with those who promote more thoughtful and effective management of ES&G issues. I also seek to draw some connections between the activities and interests of those who, broadly defined, work in these two disparate worlds.

As discussed previously, investing is about appropriately perceiving risk and reward and making decisions about what (and when) to buy and sell over a period of time. Accordingly, I begin with a review of investment risk, which sounds like a simple concept but is not. I then describe some of the more commonly used techniques to identify and evaluate companies whose securities may (or may not) be appropriate candidates to add to an investment portfolio and to identify portfolio components to which investor exposure should, perhaps, be reduced or eliminated. To do this effectively, you must understand what investment risk is and be able to distinguish among different types and sources of risk to either your own capital or funds entrusted by someone else.

Risk

The value of a share of stock today is, in theory, the net present value of all the future cash flows that will be generated by the company that issued the share, divided by the number of shares. In other words, each share represents the pro rata portion of all the wealth that the company will create in the future, discounted to today. Obviously, a great many factors influence how much actual wealth any particular firm will generate through its activities. The further into the future you extend predictions about any of them, the more uncertain these estimates become.

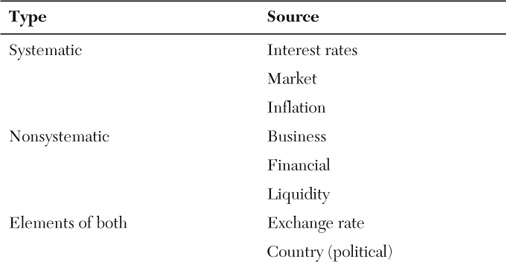

Nevertheless, it is possible to characterize the different factors that may influence a company’s fortunes and to understand how they differ. Table 6-5 shows some of the important distinctions between some of these factors and the risks they imply. Simply stated, systematic risks apply to all companies operating in an economy and include a number of aspects of the overall economic climate, such as interest rates and inflation. No individual firm can entirely escape the influence of these factors, nor can any one company change them. In contrast, nonsystematic risks are specific to a particular firm and include such factors as which lines of business the company chooses to pursue, its financing arrangements, and its management of cash. The remaining factors listed in the table have characteristics of both types of investment risk, in that they are both “macro level” concerns but also can be managed or avoided by choosing in which geographies and economies the firm operates.

Table 6-5. Sources and Types of Investment Risk

To mitigate these risks while seeking and exploiting opportunities to generate positive returns for investors, money managers employ a number of different methods. As discussed previously, one basic strategy fundamental to professional investing is diversification—employing the portfolio approach. Building a portfolio commonly involves diversification across several dimensions: changing the number of securities held, holding different asset classes (stocks, bonds, CDs), and adroit consideration of different economic sectors and industries to both diversify and limit risk to changing economic conditions.

In portfolio development, the investor seeks to position the investment holdings along the “efficient frontier.” Investment theory holds that it is possible to optimize the relationship between risk and reward through diversification. If you were to plot risk versus reward on a line graph, the efficient frontier would be the curved line along which the maximum reward could be obtained for a given level of risk. Conversely, you would find the minimum risk required to generate a given level of reward. All the points along this line yield an identical expected value. Where a particular investor would want to position a portfolio would (or should) be based on his or her investment goals and risk tolerance. An important corollary is that all points off of the efficient frontier represent inferior solutions. This means that investing according to their locations on the graph (such as by investing solely in a small number of very high-growth companies) is likely to yield a suboptimal result. For example, you might take on too much risk in pursuit of large gains, or achieve lower returns than would be possible with an optimally constructed portfolio having the same risk exposure.

The implications of this set of relationships are profound, from the standpoint of constructing and managing an investment portfolio. Accepting the notion of an efficient frontier imposes a discipline on the investor and his or her behavior. This manifests itself in an unwillingness to pay more for a security than is justified by both its future earnings potential and risk profile. Quantitatively, the relationship between risk and reward can be expressed through the use of the Capital Asset Pricing Model. In a simplified, normalized form, it states that the required rate of return for a given security is equal to the market rate of return multiplied by a measure of the security’s systematic risk (called the “beta”).19 Stocks that have higher systematic risk require a higher rate of return than those that have low systematic risk.

In addition, the efficient frontier and Modern Portfolio Theory imply that firm-specific (nonsystematic) risk can be largely removed from an investment portfolio simply by diversifying. This means that professional investors are assumed to be diversified, because by not being diversified, the investor has needlessly taken on a possibly significant source of risk. And as you saw previously, this would be viewed as a breach of fiduciary duty (and possibly state securities law) if the investor is managing funds on behalf of someone else in a fiduciary capacity. Viewed in this context, “risk” is not what we tend to think it is (losing our investment). Instead, it is volatility in returns. Portfolio volatility (or its inverse, stability) is an important concept that the investing public often overlooks—at least when markets are rising.

Reward (Given an Understanding of Risk)

The flip side of risk is, of course, reward. This topic captivates the public and is the focal point of most investor communication with clients. Potential reward to the investor may take one or more forms. The market prices of stocks held in the portfolio may increase, as may dividend payments over time. Bond prices may increase if and as the issuer’s credit rating improves and/or interest rates more generally decline. For these pleasant developments to occur, generally speaking, the firm issuing the securities must achieve sustained improvements among one or more of the three determinants of value highlighted at the beginning of this chapter: revenue growth, earnings or cash flow growth, or risk reduction.

Most of the conventional methods for evaluating and valuing company securities involve assessing these endpoints and/or factors or conditions that have some direct relationship to them. I review some of the more commonly used methods in this section.

One basic approach is technical analysis. This method involves forecasting price fluctuations, focusing on supply and demand conditions that may apply to a particular security. To the technical analyst, sometimes called a “chartist,” the causes of these fluctuations are unimportant. He or she is simply trying to find out whether excess supply (or demand) for a stock can be detected by analyzing patterns of price fluctuations or movement in indicators or rules. Technical analysis focuses on momentum—trends in price and/or earnings growth rather than on more fundamental factors. Because technical analysis is not based on causal factors, its relationship to the ES&G factors considered in this book is minimal, if not nonexistent, so I will not consider it further here. The important point to understand is that investors relying chiefly (or solely) on technical analysis exist, although they are likely to be a small minority. Also, the ES&G value-creation message I promote in this book (and that others share) is not likely to have any influence on this constituency.

The other major approach used in investing is fundamental security analysis. Typically, this method proceeds in steps, as discussed earlier in this chapter, beginning at the top. Analysts examine, sequentially, the economy and market conditions, major sectors and industries, and, finally, individual companies. At the level of the firm, investors and analysts apply several different types of analysis. Typically, these include net present value analysis (again, the current value of future cash flows), multiplier analysis (discussed later), and, in some cases, other techniques.

First, the overall economy and markets are evaluated. This is important because it has been shown empirically that general economic and market conditions typically account for between one-quarter and one-half of the variability in company earnings from period to period. Moreover, in many cases, stock prices have led the wider economy, particularly out of economic downturns. The state of the capital markets and investor confidence (or lack thereof) can affect the rate of return investors require to accept the risk of acquiring certain securities. This phenomenon was vividly illustrated during the recent global economic meltdown when, for example, the interest rate on high-yield corporate securities (junk bonds) soared and prices plummeted, regardless of individual issuer characteristics.

When evaluating the effect of big-picture concerns on an investment portfolio, investors consider such factors as the current stage of the economic cycle (are we in strong growth or facing a looming recession, for example), rates of inflation, interest rates, and the expected overall levels of corporate profits. Although these factors affect all companies, some of them tend to affect certain types of industries (and firms within them) more strongly than others. For example, if inflationary pressures are gathering force and interest rates are rising significantly, many investors avoid companies (and even entire economic sectors) that are sensitive to this factor, such as, residential construction and some types of banking.

The next step of the analysis is performed at the sector and industry level. Depending on the principal information sources used and their own preferences, analysts organize the firms in the economy into approximately 12 sectors, many of which contain a number of distinct industries. Table 6-6 shows commonly evaluated sectors and a sample of the major industries within each.

Table 6-6. Major Economic Sectors and Illustrative Industries

Again, investors will carefully consider which sectors and industries offer favorable prospects in light of macro-level factors and their particular return expectations and risk tolerance. They will evaluate, at the sector and industry level, growth opportunities (as a function of industry/market maturity and other factors), protection against economic downturns, cyclicality of revenue streams, and sensitivity to interest rates and other factors.

In particular, perceived opportunities to grow revenue in a nonlinear fashion can substantially boost the appeal of a particular company or industry with investors. The huge influx of investment funds into many forms of renewable energy during the past several years is a good example. It has in many ways paralleled the growth (and pitfalls) of investing in previous “hot” technologies such as biotechnology, the Internet, and wireless communications.

It is important for those interested in promoting corporate sustainability to understand that, as shown here, investor behavior is influenced by many factors beyond whether and to what extent a particular firm has advanced sustainability management practices. With that said, whatever the circumstances of a particular sector or industry, firms in even less dynamic, slower-growing sectors can show leadership and distinguish themselves among their peers by putting in place the policies, goals, and infrastructure described in Chapter 5. In doing so, it is important that they at least consider how they can improve their performance with respect to some of the factors I will consider next—those that investors use to evaluate individual companies.

As noted previously, as an initial matter, the investor is faced with only one question when considering a particular stock, bond, or other investment for a portfolio: Should I add, remove, or hold this security? The appropriate answer to this question is influenced by two related questions:

• What is it worth?

• Is it priced correctly?

The answer to the second can be readily deduced by comparing the answer to the first (the true value) with the current price on the market, assuming that we are discussing a reasonably liquid security issued on a major market exchange. So essentially, the task (and much of investment analysis) involves determining the security’s true value.

There are several ways to accomplish this. The true value is equal to the net present value of all the firm’s future cash flows, discounted to today’s terms using an appropriate rate. Many professional investors and, certainly, the larger information providers and money managers have detailed knowledge of company operations and sophisticated models with which to perform the necessary calculations. Such discounted cash flow (DCF) models are in common use throughout the financial services industry and in academia as well.

Another approach to both inform the development of estimates to use in DCF models and to perform screening and periodic evaluation of individual securities is to use ratio analysis. I present some commonly used ratios in Table 6-7 and then discuss them briefly.

Table 6-7. Commonly Used Financial Ratios Applied to Company-Level Analysis

In either case, the investor or analyst is seeking hidden value and/or risk. Recall that the market has already rendered a judgment about the current value of any security that is liquid and frequently traded. The question then is, have market participants overlooked anything that might affect the company’s future revenues, earnings, or cash flows? Or have they overlooked latent sources of risk that could jeopardize anticipated financial results? So those seeking to outperform the market are constantly looking for what is unrecognized but important, and also what might change in the future and in what ways. Those interested in corporate sustainability tend to believe that ES&G issues and how they are managed provide significant and tangible examples of some of these latent factors. And based on the published literature (discussed in depth in the next chapter), there is reason to believe that their views have been substantiated. I will introduce and discuss ES&G investing in greater depth shortly. For now, however, it is important to return to the types of endpoints that are familiar terrain for the investment analyst. In this way, as we consider new sources of value that can be created by ES&G improvements, we will be able to put them into terms that will be accessible to and valued by the professional investor.

Again, investors consider both risk and reward and try to strike a reasonable balance between them.20 Typical reward factors include profitability, cash flow, efficiency/productivity, and growth. Risk factors include capital structure, liquidity, and cash flow (or the lack thereof).

Commonly, these factors are evaluated through the use of ratios, which compare one number (such as net profit) to another (such as sales). Most of the data required to compute traditional financial ratios is directly available from the company’s financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement). Because these data must be reported at regular, defined intervals, must be calculated according to certain conventions, and must be independently audited,21 they have certain attributes that are extremely helpful to the analyst.

Specifically, financial accounting data reported by companies are provided on a timely basis and are (presumably) accurate, consistent, comparable across time periods and organizations, reliable, and meaningful within the context in which they are reported and used. Many observers have questioned whether this information set and reporting conventions (which date from the 1930s or earlier) adequately capture the current workings of a company’s operations and performance or provide much insight into its future prospects. This topic is explored further in Chapter 8. In any event, there can be no doubt that having a set of independently validated data describing each company’s financial results is of great utility to the financial analyst or investor.

Some commonly used ratios are listed in Table 6-7. I provide these here without significant elaboration simply to make the point that these types of basic indicators are in widespread use, are limited in number, and are not mathematically complex. Moreover, most can be readily found (already computed) on many investment company and financial web sites (such as, those of Charles Schwab, Morning-star, and the Wall Street Journal). These types of data are part of the common language of “Wall Street” and must be understood, at least at a general level, to address investors’ concerns. In addition, some of the published literature on the relationships between ES&G issues and corporate financial results and investment returns reviewed in Chapter 7 refers specifically to these ratios.

Briefly, the categories listed in Table 6-7 and the ratios within each are meaningful in the following respects:

• Profitability ratios. Return on equity, assets, or sales provides insight into how well the company (and its management) are converting invested capital (equity), materials, plant and equipment, (assets), or funds paid by customers (sales) into profits. High profitability ratios are considered to be a good indication that the firm is converting the resources entrusted to it into profits effectively. A high ROE is particularly prized by investors.

• Efficiency ratios. Sales normalized by inventory, net working capital (which includes inventory), or assets tell the analyst how well and quickly the firm is converting its available resources into new sales. As discussed previously, vigorous and growing sales are the lifeblood of any business, particularly one seeking new investment capital.

• Growth. In a related vein, substantial return opportunity is intimately tied to company growth rates, both in an absolute sense and as indicated by certain key ratios, such as, price/earnings:growth (PEG). The PEG normalizes the P/E multiple (discussed in a moment) by the firm’s growth rate. Firms with a PEG ratio less than unity (ones that are growing faster than their price-earnings multiple) are often viewed as promising investment candidates.

• Liquidity. Although true investors are primarily interested in long-term return prospects, it is widely understood that there will be no long term unless the firm is continuously managed properly in the short term. This includes having adequate liquid financial resources to meet the company’s ongoing needs and obligations. Liquidity ratios, such as, those listed in Table 6-7, provide a quantitative measure of what sort of “cushion” of cash and other liquid assets the company has, relative to its short-term financial obligations. Generally, investors (and most lenders) like to see several times more short-term assets than short-term liabilities. This ensures that it is unlikely that the firm will run short of cash, even in the wake of an emergency or significant unexpected event.

• Other ratios. Several other ratios are important and are often used by analysts and investors to develop a sense of a company’s position and prospects. The debt/equity ratio (or “leverage”) quantifies how much of the firm’s capital has been contributed by investors versus borrowed from lenders or secured by debt. A high debt/equity ratio (high leverage) indicates greater risk, due to the cash drain from the associated regular interest payments, which have the effect of reducing profits. The price/earnings (P/E) ratio is widely followed. It indicates the multiple of a company’s current earnings at which the firm’s stock price (per share) is selling. Historically, the P/E for all publicly traded stocks in the U.S. has averaged about 14, but during bull markets (not to mention market bubbles) the P/E can regularly exceed 20. The bond rating and stock beta (discussed earlier) indicate the risk of a company’s fixed income and equity securities, respectively. Higher bond ratings mean lower interest rates (and costs), due to lower perceived risks of default by the issuer. In contrast, a high beta means higher-than-market stock price volatility (risk), and hence, a higher required rate of return. Finally, a stock’s yield is the value of the firm’s annual dividend payment per share divided by its stock price. The average yield for U.S. stocks in recent years is about 2 percent, which is well below long-term historical averages. It is worthy of note, however, that dividend payments have represented a majority of the total return provided by U.S. stocks over the past 30 years or so.

In addition to these conventional types of financial measures, a number of alternative frameworks and methods have emerged in recent years that provide a means by which investments may be evaluated. I will briefly mention two that have attracted their own following and that may be of interest to particular types of organizations. One is Economic Value Added (EVA), which is a technique invented (and copyrighted) by the firm Stern Stewart. EVA provides a method by which a company, or a component thereof, can be rigorously evaluated according to its value-creation performance. It takes the profit or earnings produced by the company, a market segment, or even a single production line and considers (subtracts) the cost of the capital that was required to produce that profit.22 Entities (or subunits) that have a positive result (that earned more than their cost of capital) have created value. Those with a negative result have, in effect, destroyed a portion of their organization’s available capital, notwithstanding the fact that they generated positive earnings on a financial accounting basis. EVA provides some real analytical power to company and segment evaluation and is in use in a wide array of companies. Those interested in promoting corporate sustainability should be aware of this technique. Its usage involves no new endpoints or variables, but it does bring a tight focus to one of the themes of this book—value creation in a true sense.