9. Better Tomorrow at Sodexo North America

Jan Bell, Weintraub Professor of Accounting, S. Sinan Erzurumlu, Assistant Professor of Technology and Operations Management, and Holly Fowler, Babson College MBA 2010, prepared this case solely from external documents as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

Copyright © 2012 Jan Bell, S. Sinan Erzurumlu, and Holly Fowler. Please do not cite or use without permission.

Introduction

In March 2010, Sodexo, a global leading food and facilities management services company, signed a three-year agreement with World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to work together on environmental and supply chain issues. Suzanne Apple, Vice President and Managing Director, Business and Industry at WWF, was excited about the agreement:

“When we first began talking with Sodexo, it was very much around key areas that they could control in their operations, such as energy and water use. Through this collaboration, we have expanded this focus outside Sodexo to the supply chain on improving the sustainability of key agricultural commodities like beef, dairy, palm oil, soy, and tropical fruits. It’s quite an extensive partnership looking at the source and impacts of food products for Sodexo, its clients, and consumers.”1

1 Sodexo, “Fiscal 2011 Corporate Citizenship Progress Review,” http://onlinereportsfy2011.sodexo.com/corporate-citizenship-report/, p. 5, accessed November 30, 2012.

This agreement marked a milestone in Sodexo’s efforts to become a global sustainability leader that started over a decade ago. In the late ’90s Sodexo actively engaged in philanthropy, but with society’s growing interest in and heightened understanding of sustainability, Sodexo expanded its efforts in the 2000s to include environmental and social issues. The company first appeared in the FTSE4Good Index in 2001, signed the United Nations (UN) Global Compact in 2003, and formally integrated sustainability into its business plan in 2005. Because Sodexo serves more than 50,000 million consumers daily in more than 80 countries, management recognized that the company could significantly impact others through its sustainability efforts.2 Damien Verdier, Sodexo’s Group Executive Vice President, Chief Marketing Officer Client Retention, Offer Marketing, Supply Chain and Sustainable Development, gave his point of view on Sodexo’s potential impact:

2 www.sodexousa.com/usen/aboutus/aboutus.asp, accessed November 15, 2012.

“Companies such as Sodexo are uniquely positioned to identify priorities and establish action plans for improving sourcing and industrial practices. The Corporate sector has a major role to play to lead a current discussion on future challenges. The companies will help to evolve behaviors through their powerful stakeholder network.”3

3 Sodexo, “Corporate Citizenship Progress Review,” p.5.

In 2009, Sodexo announced its strategic sustainability plan, known as the Better Tomorrow Plan (BTP), which encompassed both broad and specific commitments for sustainability and corporate social responsibility.4 The plan was the cornerstone of establishing Sodexo as a responsible company (their “We Are” promise). It contained 14 commitments (see Exhibit 1), each with clear metrics, oriented around three main areas: protecting and restoring the environment, supporting local community development, and promoting health and wellness, composing the “We Do” portion of their strategy. Lastly, the plan promised that Sodexo would dialogue and plan actions jointly with stakeholders, composing their “We Engage” commitment.

4 For a Sodexo video explaining the BTP, go to http://onlinereportsfy2011.sodexo.com/corporate-citizenship-report/.

With the BTP, Sodexo ambitiously set its sustainability targets to substantially increase its performance by 2020. Achievement of targets required not only changes by Sodexo’s external value chain members, most importantly suppliers, clients, and their customers, but also changes in internal operations worldwide. Management was ready to lead this change since they viewed sustainability as a way for Sodexo to become a more socially and environmentally responsible company, to improve their customer value proposition, and to reduce their costs, improve their margins, and increase their profitability.

Sodexo: Corporate Overview

Sodexo, a multinational company founded in 1966 in France by Pierre Bellon, was built on his family’s experience of more than 60 years in maritime catering for luxury liners and cruise ships. By 2012, the company designed, managed, and delivered comprehensive onsite services for corporate, healthcare, assisted living, education, government, defense, sports and leisure, and justice clients. Sodexo contributed to client organizations’ performance in three key areas: their people, processes, and infrastructure and equipment. Michel Landel, the Global (Group) Chief Executive Officer and Member of the Board of Directors of Sodexo, identified Sodexo’s mission as follows: “Since Sodexo’s creation by Pierre Bellon in 1966, our mission has been twofold: to improve the Quality of Life of the people we serve every day and to contribute to the economic, social, and environmental development of the communities, regions, and countries in which we operate.”5

5 Sodexo, “Corporate Citizenship Progress Review,” p. 4.

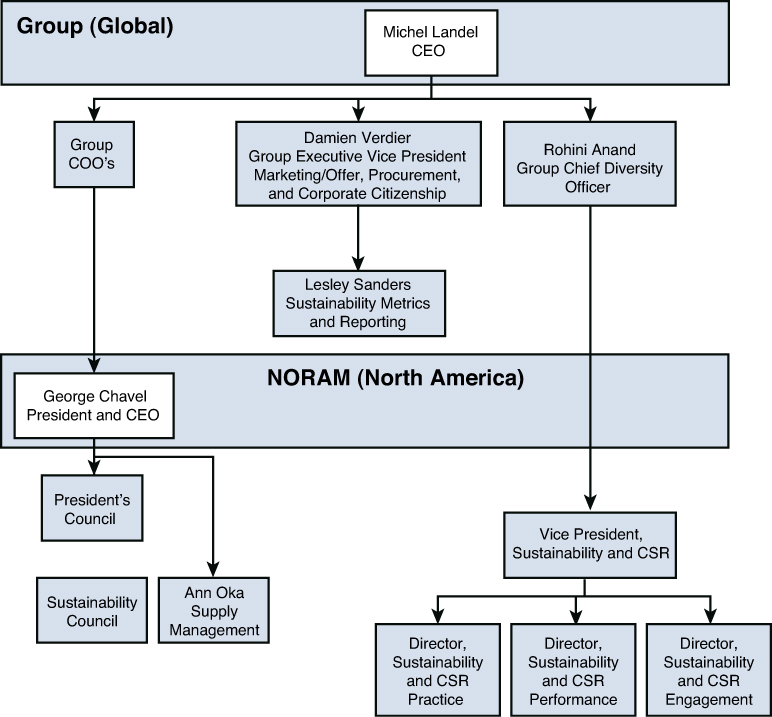

In 2012, Sodexo reported over 18.2 billion euros in consolidated revenues, employed 391,000 people, and operated 33,400 clients’ sites serving 50 million consumers in 80 countries around the world. Exhibit 2 contains Sodexo’s income statement and the breakdown of its revenue by region for the fiscal years 2012 and 2011, and Exhibit 3 presents revenue by market segment for North America. As Sodexo grew internationally, it was organized geographically with presidents and CEOs for North America (NORAM), Europe, and Asia/Australia responsible for Sodexo’s markets (corporate, healthcare, education, and other). Decision making, guided by group strategic plans, was decentralized. These presidents reported to Michel Landel, who oversaw all global functions and operations. Exhibit 4 contains an abbreviated organizational chart for Sodexo’s Group and NORAM operations.

As international attention to environmental and social concerns grew in the 1990s, Sodexo was rapidly expanding. This growth not only propelled Sodexo to the forefront of its industry, but brought with it a new visibility as a global company. With operations in almost 80 counties, hundreds of thousands of employees, and tens of thousands of client sites, Sodexo faced higher scrutiny. Sodexo was increasingly aware that socially and culturally acceptable business practices in some parts of the world put Sodexo’s business integrity at risk. Not surprisingly, the company, with its size and global focus, also felt the pressure of increased demands by external stakeholders for information about its sustainability efforts. In particular, in the early 2000s, the growing interest of clients for sustainable alternatives in their food and facilities management demanded sustainable products and services.

Supply Management Group

With geographically dispersed client sites and the need to provide numerous, diverse items, Sodexo’s supply chain management process was paramount to its success and to the success of sustainability efforts. The Supply Management Group (SMG) managed its clients’ purchase orders and arranged delivery to sites using a network of distributors. Because it consolidated purchases across clients, Sodexo was one of the largest sourcing organizations, a fact that provided significant leverage with all of its vendors. Sodexo’s SMG procured products from a massive network of suppliers efficiently and quickly. Further, SMG played a key role in delivering value to clients through providing favorable product pricing, guiding them to source items that increased gross margin, and reducing their business risks.

Product Pricing

The SMG secured favorable purchase prices for its clients by aggregating volume in its contracts on a national and regional basis through an on-demand electronic communication system. Sodexo would receive contract and performance data about its suppliers. Based on the supplier data, Sodexo not only negotiated competitive pricing for contract requirements but also implemented stringent food safety programs, indemnity and insurance programs, support and data management for its clients. To maintain favorable pricing, the SMG routinely scanned the market for vendors that might be willing to provide favorable pricing and required the reconsideration of all supplier contracts regularly.6

6 www.sodexousa.com/usen/newsroom/press/press11/supplymanagementworldclass.asp, accessed November 30, 2012.

Increasing Gross Margins

The SMG stimulated the sales of specific products and services (produce, packaging, and so on) by educating clients about compliant products and their impact on cost reduction and/or increased sales revenue. Sodexo’s teams of supply managers served as liaisons between the SMG and site managers. This team communicated with site managers regularly to make them aware of the list of approved vendors and preferred products. As a result, purchases generated large vendor allowances for Sodexo, lowered quoted contract prices for the sites, and afforded sites to offer “specials” that stimulated sales. These revenue management actions improved client satisfaction and retention.7

7 http://uk.sodexo.com/uken/about-us/purchasing/purchasing.asp, accessed November 30, 2012.

Reducing Clients’ Business Risk

To ensure sustained quality, availability, and service, the SMG evaluated all existing and potential suppliers regularly on numerous factors, including but not limited to product availability, ability to meet demand, overall value (as defined by product quality over price), service level, and ability to meet Sodexo’s quality requirements. Additionally, all of Sodexo’s selected suppliers were required to sign a Supplier Code of Conduct committing to deliver on these factors and to pass business reviews. In addition, Sodexo designated independent third-party auditing firms to inspect contracted suppliers annually. During this audit, all areas of a supplier’s operations were reviewed from the arrival of raw materials to manufacturing, storage, and shipment.8

8 http://uk.sodexo.com/uken/Images/Supplier%20code%20of%20practice%202011_tcm15-50823.pdf, accessed November 30, 2012.

Taken together, the SMG’s activities had a positive impact on both client satisfaction and retention. The group also contributed to Sodexo’s business model. Vendor allowances increased Sodexo’s own gross margin, because not all the benefit of consolidating demand across clients was flowed through to clients.

The Better Tomorrow Plan

To achieve the BTP’s 14 commitments, in 2009 Sodexo embarked on an internal action plan and started proactively interacting with SMG on issues involving environment, energy and emissions, water and effluents, and materials and waste. Lesley Sander, a global Subject Matter Leader for Sustainable Supply Chain Initiatives, summarized Sodexo’s challenge this way: “Sodexo employs over 391,000 people throughout the world, and millions more work for the companies in our supply chain. Our challenge is to ensure that all the products and services we source are produced according to widely accepted social, environmental and ethical standards.”9

9 Sodexo, “Corporate Citizenship Progress Review,” p. 64.

Sodexo’s supply chain strategy was built for long-term, transparent relationships with a group of suppliers who would provide significant quantities of products for Sodexo’s activities worldwide. Sodexo had to ensure that these products had low impact in accordance with recognized environmental and social standards. This challenge was accepted by George Chavel, Corporate Executive Officer NORAM, and Arlin Wasserman, VP Sustainability North America, who said in 2010, “The products we source, whether food or equipment, are some of the most important parts of our environmental footprint. We are continuing to partner with our suppliers to drive sustainability practices throughout the supply chain. We include sustainability in our regular business reviews with them and last year launched our first ‘Better Tomorrow’ awards for suppliers.”10

10 Sodexo, “North America, 2010 Corporate Social Responsibility Report,” http://bettertomorrow.sodexousa.com/s/, accessed November 30, 2012.

The BTP set out detailed and time-bound objectives that would improve the sustainability of the supply chain. For example, Sodexo made commitments to source only cage-free shelled eggs by July 2014 and to eliminate the use of pig gestation stalls in its supply chain by 2022, plans that were praised by the Humane Society. Sodexo also promised to ensure compliance with a Global Sustainable Supply Chain Code of Conduct in all the countries that the company operated, as well as to source local, seasonal, or sustainably grown or raised products. The company set goals to reduce its carbon and water footprint, and to reduce organic and nonorganic waste in all the countries and at clients’ sites by 2020.11

11 Sodexo, “Corporate Citizenship Progress Review,” p. 39.

To guarantee sustainability throughout the supply chain, Sodexo had to make considerable changes in its supply chain starting with a revision of its Supplier Code of Conduct. The code was extended to include social and environmental factors in its multicriteria supplier assessment. The Group appointed a team to review its Global Supplier Code of Conduct. The extensive review was finalized in April 2011, and the revised document requested that suppliers keep Sodexo informed about their progress on actions and improvement plans to comply. In this new agreement, each supplier would review and improve existing Group supply chain standards relating to nutrition, food safety, the environment, human rights, labor standards, general business ethics, transparency, contaminants, and additives.12

12 Sodexo, “Corporate Citizenship Progress Review,” p. 66.

Sustainability Strategy and Priorities at Sodexo North America

Sodexo North America (NORAM), with roughly 40% of Sodexo’s business activities, formed the Office of Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility in 2007 to respond to the growing demand of NORAM clients for sustainable alternatives in their food and facilities management. Three years later George Chavel, CEO of NORAM, announced, “[In our first performance-based sustainability report for North America] we provide baseline data for key aspects of sustainability performance, the necessary first step to track our progress. The ‘Better Tomorrow Plan’ is designed to leverage our scale by implementing key initiatives across our entire enterprise that includes some 10,000 sites we serve. As a result: Nearly half of our contracted seafood is now sustainably certified; and we almost doubled our percentage of fairly traded coffee purchases between 2009 and 2010.”13

13 Sodexo, “Corporate Social Responsibility Report,” p. 4.

From Chavel’s statement, it appeared that NORAM’s first sustainability priorities had been seafood and fair-trade coffee for clients. While NORAM’s plans and achievements were welcomed, Sodexo’s North American clients might wonder why these particular initiatives were pursued first and what would come next in Sodexo’s efforts. Some clients were already developing their own initiatives specific to their concerns and wanted quick action from Sodexo on issues of importance to them.

NORAM’s actions between 2007 and 2010 followed Sodexo Group’s efforts to establish itself as a sustainable company. Prior to this, NORAM had launched and discontinued a food offering that it advertised as environmentally friendly, but which faced criticism for lacking sound science. To demonstrate its commitment to the environment, NORAM decided that it needed to hire and develop subject matters experts, agree on a sustainability strategy, and establish a decision-making process. The Presidents Council, composed of the markets’ presidents, would make final decisions on sustainability, setting priorities and establishing integrated operational approaches across markets. The President’s Council received recommendations from the Sustainability Council, led by NORAM’s Senior Vice President for Strategy.

The Sustainability Council was composed of sustainability champions from Sodexo’s markets. The Vice President of the Office of Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility, a subject matter expert and a member of the Sustainability Council, facilitated the development of Sodexo’s sustainability strategy through the council. That VP was also responsible for measuring sustainability performance and for leading strategic stakeholder engagement. Those processes informed the Council’s recommendations to the Presidents Council.

To ensure that diverse stakeholder voices informed its sustainability strategy and priorities, NORAM selected Ceres to manage stakeholder engagement. Ceres is a national network of investors, environmental organizations, and other public interest groups dedicated to sustainability. Ceres was responsible for determining the priorities that dominated its stakeholder groups and for ensuring that NORAM’s goals reflected those priorities and not simply what could easily be accomplished.

In its 2010 Sustainability report, Sodexo reported that based on its business model and stakeholder concerns, 16 sustainability issues were important to address through the sustainability strategy in North America:

• Climate Change

• Water Quantity and Quality

• Food Waste

• Packaging Waste

• Fairly and Responsibly Traded Products from Tropical Regions

• Locally Sourced Farm and Ranch Products

• Sustainability in the Mainstream Food Supply

• Sustainable Seafood

• Healthy Food with Reduced Sugar, Salt, and Fats

• Vegetarian and Vegan Options

• Promoting Overall Wellness and Physical Activity

• Diversity

• Supplier Diversity

• Employee Engagement

• Fighting Global Hunger

Guided by the Ceres managed stakeholder panel, in its 2010 CSR report, Sodexo stated that its 2011 focus would be on its strategy for healthy, sustainable food and its approach to energy and climate change. The stakeholder panel narrowed NORAM’s 2011 focus from 16 items to a manageable few so that meaningful performance goals could be established and impact measured.14

14 Sodexo, “Corporate Social Responsibility Report,” pp. 17–19.

“We Do” Protect the Environment at NORAM

In March 2010, the WWF and Sodexo signed a three-year agreement to address environmental and supply chain issues across the globe. The collaboration between the two organizations focused on identifying key areas of concern, promoting sustainable supply chain practices, and measuring the results of practices. Measuring progress and impacts from Sodexo’s operations involved collaboration with suppliers and clients. On the supply side, NORAM used corporate-wide purchasing data to make sustainability changes and track progress on issues that they could influence in their supply chain—for example, fair trade coffee and sustainable seafood.15 These items were easy to track and report because they had well-established standards that defined what terms meant, well-established certifying groups existed that could trace the chain of control and issue compliance certificates, and expenditures on them could be tracked by Sodexo’s systems. But measuring services presented a challenge because NORAM typically operated only a portion of client’s site, and data, if it existed, existed for the entire site. And for certain items, such as “locally grown produce,” no definitions existed that were commonly shared by Sodexo’s stakeholders. But as acknowledged by management, “Sodexo’s measurement tools and practices currently under development will be a key differentiator.”16 In 2010, NORAM focused on measuring baseline performance, whereas in the fiscal year of 2011, Sodexo worked closely with the WWF to define standards and guidelines on environmental issues with an intention to understand the risks and opportunities for Sodexo’s business.

15 Ibid., p. 20.

16 www.sodexousa.com/usen/newsroom/press/press09/bettertomorrowplan.asp, accessed November 15, 2012.

Despite challenges, a close examination of efforts in four key areas targeted in the BTP demonstrates Sodexo’s progress toward its commitments.

Energy and Emissions

Climate change is projected to cause damage to natural ecosystems over the coming decades with rising temperatures and sea levels. The consequences of climate change are expected to become the leading cause of supply chain disruptions in the near future. Reducing the severity of climate change in future years by lowering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is critical to managing risk. Sodexo’s two biggest sources of climate-altering GHG emissions came from their supply chain (particularly the supply chain for agricultural products) and from operating commercial buildings at their clients’ sites. Further, the waste produced at client sites from food operations managed by Sodexo represented another source of GHG emissions.

NORAM launched a twofold effort to measure and reduce its carbon footprint. First, NORAM had to induce clients and suppliers to make basic behavioral changes. This was difficult in NORAM’s food services supply chain because it relied on an agricultural community that directly controlled its production methods. Further, NORAM’s clients wanted variety in food choices that led to energy consumption in both transportation and waste. Second, NORAM advocated site-level actions that would lead to energy efficiency in facilities. These actions ranged from installing energy-efficient equipment to using alternative sources of energy (see Exhibit 5 for an extensive list). Progress in these areas would establish NORAM as an important partner in its clients’ sustainability efforts and could lead to lower operating expenses.

Measuring NORAM’s direct energy consumption for the services they provided was challenging because the company needed to meter the consumption at 700 clients’ sites separately, and they did not yet have a reliable measure of energy use across the clients’ sites.17 The WWF helped Sodexo to develop protocols and establish a framework for measuring and reporting on GHG emissions. As part of its environmental management, Sodexo set up procedures, implemented measures, helped obtain certifications and labels, and, in an increasing number of cases, applied for certification under the international environmental management standards: ISO 14001, HQE, LEED, or equivalent. In the case of tracking Sodexo’s own carbon emissions, NORAM implemented a methodology for the calculation of its Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions that is consistent with World Resources Institute’s (WRI) GHG Protocol. This widely used approach related scope 1 emissions to those released when a fuel was burned at a facility owned by the company; scope 2 emissions to those released, not at the company’s facilities, but at the utility power plants where the electricity purchased by the company was produced; and scope 3 emissions to those released by a company’s suppliers, and other sources. Use of the WRI protocol determined that much of onsite emissions and the supply chain emissions fell into Sodexo’s clients’ scope 1 and 2, and into Sodexo’s scope 3 emission categories. Based on the measurements, NORAM publicly disclosed emission through the Carbon Disclosure Project (see Exhibit 6).18

17 Sodexo, “Corporate Social Responsibility Report,” p. 21.

18 Ibid., p. 22.

Water and Effluents

A third of the world’s population lived in water-stressed countries in 2010, and severe water shortages were growing in the U.S. and around the world due to overabstraction, fragmentation, pollution, climate change, and the ever-increasing demands of a growing global population. According to the UN, although a person needs five liters per day for drinking and daily activities, the energy and products a consumer uses daily take tens of thousands of liters to produce. Consumption will soar further as more people expect Western-style lifestyles and diets; for example, one kilogram of grain-fed beef needs at least 15 cubic meters of water, whereas a kilo of cereal needs only about 3 cubic meters. In 2011, the UN General Assembly declared access to clean water and sanitation a human right, but more than three billion people lacked access to one or both.

Sodexo’s operations depended on an abundant and clean supply of water, and water scarcity would impact its supply chain and pricing as well as the viability of its communities. Many of the actions needed to reduce Sodexo’s impact on water supplies would save money and provide greater value to its clients. Yet only 23% of client sites at NORAM implemented all site-level actions for water conservation, including the installation of water-saving taps, water-efficient equipment, and water recycling systems, or participated in a detailed water-efficiency audit (see Exhibit 7). In 2010, NORAM started collecting the first baseline of performance of water use at Sodexo’s corporate-owned sites where the company had the greatest control. NORAM’s water footprint—the water used in direct operations—was over 500 million gallons used at the laundries, a few conference centers, and other leased spaces in North America. Sodexo also began to track its efforts to influence behaviors and systems that would reduce water consumption.19

19 Sodexo, “Corporate Social Responsibility Report,” p. 25.

Local, Seasonal, or Sustainably Grown or Raised Products

Agriculture consumes a large percentage of the world’s water, produces a large share of GHG emissions, and also provides jobs to a large share of the earth’s population. Lesley Sander, Subject Matter Leader for Sustainable Supply Chain Initiatives, stressed agriculture’s impact on the environment: “Agriculture can have a significant impact over GHG emissions, water consumption, pollution, and deforestation. It also potentially harms health through the use of pesticides, fertilizers, and antibiotics.” The food and agriculture sector took up half of the earth’s habitable land, used two-thirds of the world’s freshwater resources, and consumed more than 10% of all energy in 2011. During that year, at least one in four people in the world was poor and worked in agriculture.

Jim Pazzanese, VP of Supply Chain Management, explained clients’ expectations and Sodexo’s response: “People want to know where their food comes from. At the same time, North American consumers are...increasingly looking to companies like Sodexo to make good choices for them about what to eat. Right now, there’s quite a bit of attention on purchasing local. Sodexo works to integrate local farmers into our existing distribution channels. We are using our size to create demand for local products and then assisting in getting those local products to be warehoused by our produce distributors.”20

20 “Working Toward a Sustainable Supply Chain,” www.bettertomorrow.sodexousa.com/newsletter/694, accessed November 19, 2012.

To encourage local and sustainably grown products, Sodexo helped new and existing suppliers or producers understand the NORAM business requirements, practices, and procedures. Using a database that features more than 600 farmers, NORAM developed a local sourcing strategy by matching local farms to distributors. This action was reinforced by Sodexo group management, which required that regional produce distributors purchase locally grown products. The company launched a new system to create a baseline measure of its success with local sourcing and found that 17% of the sourced produce fit NORAM’s definition of local produce, which is produce coming from the same state or region (see Exhibit 8 for local produce in the U.S.).21

21 Sodexo, “Corporate Social Responsibility Report,” p. 36.

By increasing the procurement of local, fair, and responsibly produced products, the company helped its clients meet a growing demand from its customers and sent an important message to its suppliers about the value of fair wages and environmental practices. For instance, NORAM collected data on NORAM’s purchases of coffee in 2009 and found that 8% and 47% of the dollar amounts purchased in the U.S. and Canada, respectively, were for Fair Trade and Rainforest Alliance–certified coffee. Then in 2010, they found that their spending on fairly and responsibly traded coffee had increased to 14% in the U.S. and 49% in Canada.22

22 Ibid., p. 34.

Sustainable Fish and Seafood

In 2008, seafood was the main source of protein for over 15% of the world’s population, and demand for seafood continues to grow. In January 2011, the USDA and Department of Health and Human Services released new dietary guidelines that encouraged all Americans to eat at least two portions of seafood a week. But overfishing and environmentally destructive fishing methods pose serious threats to the world’s seafood supply and the ocean’s ecosystems. The world’s fisheries are in collapse and, if current trends continued, they would be beyond repair by 2048.23

23 B. Worm et al., “Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services,” Science, November 3, 2006, Vol. 314.

NORAM made a commitment to source 100% of contracted seafood purchases from sources certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) or the Global Aquaculture Alliance’s (GAA) Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) by 2015 (see Exhibit 9 for sustainably certified seafood in the U.S. and Canada). The company focused on seafood products that were sourced “on contract” rather than on the total dollars spent on fish and seafood, because contracted seafood represents items over which the company has the greatest degree of control and influence. The MSC program was a global program of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to recognize sustainable fishing practices, influence consumers’ seafood purchase choices, and work with partners to transform the seafood market to a sustainable basis. When a product with the MSC eco-label was sold, each business in the chain had a Chain of Custody certificate, proving they had demonstrated to independent auditors that MSC-certified fish came from a certified supplier and was kept separate from non-MSC-certified fish.24 The GAA has similar objectives to MSC, but is concerned with certifications for hatcheries, farms, processing facilities, and feed mills. NORAM was able to make its commitment largely because standards existed to define sustainable fish and seafood, certifying agencies existed, and the supply chain was well developed.25

24 www.msc.org/about-us/standards, accessed November 19, 2012.

25 www.gaalliance.org/certification/process.php, accessed November 19, 2012.

Sodexo’s collaborations with global partners could transform the global seafood market, ensuring a safe supply for the future. Meredith Lopuch, Director of Major Buyers Initiative for Fisheries at WWF, addressed this topic this way: “We hope [Sodexo’s] commitments serve as a model for other major brands to follow as a way to reduce impact on the environment and provide customers with responsibly sourced seafood. By supporting fishery improvement projects and engaging with global sustainable seafood organizations like the Marine Stewardship Council and Aquaculture Stewardship Council, Sodexo is demonstrating the true value of collaboration.”26

26 www.sodexo.com/en/Images/more-info-sustainable-seafood342-589978.pdf

Please use this for footnote 27, referenced for Lupoch: http://www.sodexo.com/en/Images/more-info-sustainable-seafood342-589978.pdf.

Moving Forward

When Sodexo’s global management announced the 14 BTP commitments in 2009, they had determined that sustainability was the platform that would make Sodexo a more socially and environmentally responsible company, enabling it to live up to its mission. But they also believed that it would improve Sodexo’s customer value proposition, reduce its costs, improve its margins, and increase its profitability. With 40% of its global business in North America, the developments in NORAM were essential to the success of BTP.

These commitments raised multiple challenges for NORAM’s operations. First, NORAM had to deploy BTP successfully to Sodexo’s large network of suppliers and clients. Some of these commitments, such as the one related to sustainable seafood, had been successful, but the company still had to deliver achievements across all areas of BTP. Were they being opportunistic in selecting priorities and reporting results? How should their priorities be established with so many competing stakeholders’ needs and opportunities? Second, BTP demanded changes to NORAM’s internal operations. It was evident that NORAM had to leverage its sustainability goals and results to improve its client value proposition for profitability to improve and for the BTP to succeed. Third, some items in the BTP would not result in cost savings, and the sustainability goals would be expensive to drive measurable results. Clients might expect NORAM to meet those sustainability goals at its own expense. NORAM would face the option of either meeting the goals by paying the additional expense or displeasing clients by offering the sustainability items only at increased contract prices. NORAM’s site managers had been advocates of sustainability over the years, but the jury was still out to predict the future of sustainability at NORAM.

Exhibit 1 Fourteen commitments of the Better Tomorrow Plan.

Source: www.babsondining.com/sustainability/index.html, accessed November 30, 2012.

Source: Sodexo: “Solid Revenue and Profit Growth in Fiscal 2012,” www.businesswire.com, accessed November 8, 2012.

Exhibit 3 Sodexo North America’s revenues.

Source: Sodexo: “Solid Revenue and Profit Growth in Fiscal 2012,” www.businesswire.com, accessed November 8, 2012.

Exhibit 4 Sodexo Global and NORAM organizational chart.

Source: Developed by authors based on review of various Sodexo public documents, including http://bettertomorrow.sodexousa.com/s/.

http://onlinereportsfy2012.sodexo.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/RA_GB.pdf

http://onlinereportsfy2011.sodexo.com/corporate-citizenship-report/

Exhibit 5 Site-level actions for energy efficiency, Sodexo North America.

Source: Sodexo North America, 2010 “Corporate Social Responsibility Report.”

Exhibit 6 Carbon footprint, Sodexo North America.

Source: Sodexo North America, 2010 “Corporate Social Responsibility Report.”

Exhibit 7 Site-level actions for Water Conservation, Sodexo North America.

Source: Sodexo North America, 2010 “Corporate Social Responsibility Report.”