Interrogate and extrapolate

‘If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.’

ALBERT EINSTEIN

This tool can feel quite different to the others. While many of the others are about dusting off the creative part of your brain, this one can feel more logical and analytical. Which is why some people will love it and others will hate it (I’m back to Marmite again).

It’s also why it won’t work with every problem. But I’ve included it because it would be remiss not to acknowledge that some problems can be solved with rigorous, rational analysis.

Your car engine has broken down: where sidestep the issue would have you cycle or get a taxi instead, interrogate and extrapolate is about taking the engine apart, examining every cog and cable, finding what’s wrong and putting it right.

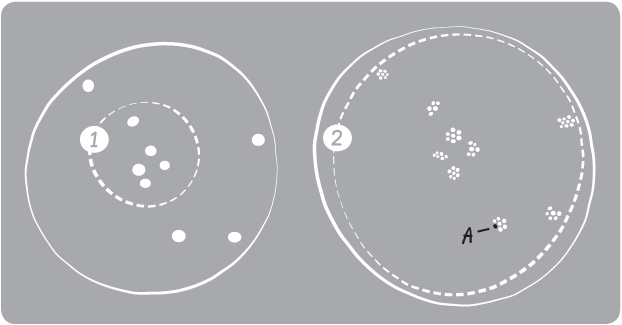

Visual

Analytical problem solving is often like (1) – it doesn’t look widely enough or deeply enough (breaking the parts into smaller elements) so the discrete nub of the issue gets missed. Only by examining every possible area, in the greatest possible detail (2), will you discover the very specific, very manageable problem (A) that needs to be solved for everything else to work.

Theory

The start of this Innovation section was think bigger, taking a step (or several steps, or a leap) back from the original problem.

This tool kind of goes the other way – breaking the problem down into small, manageable pieces and discovering (perhaps) that of those pieces, the problem only resides in one or two of them – so you only need to fix those broken pieces to solve the issue.

How come both tools are valid? Well, the nature of business problems varies wildly. And a few of those problems suit a methodical approach more than a creative one. You might think of it as the difference between something that’s objective and something that’s subjective. When it’s an objective, tangible and clearly quantifiable issue, this interrogative approach can be effective.

Seeing red

For instance, I was doing a press pass at a big printing company and we were talking about colour reproduction and checking colour accuracy. The director told me about a problem they’d had a while back when all of their work was coming out too red.

Now with modern printers (where just one press can cost £3,000,000), colour accuracy is exemplary. And expected. So it’s a whacking great problem if you, the major printer, are suddenly producing work that’s too red. Especially when you don’t know why. Is it the inks? The paper stock? The press computers? The guys operating the press? Too much ink? Too little? The way it’s drying? A problem with the varnish?

In the end, by going through every step of the process and examining them individually, they discovered the problem was … meat lamps.

Let me explain. Printers use viewing booths with special lighting so they can check colours accurately by eye. Your normal office strip lights just aren’t clean enough. Supermarkets use special lighting too, in their meat refrigerators. Lights that emit a lot of red. To make the meat seem … redder. Meatier. The tricksters.

And by mistake somebody had fitted the print viewing booth with those meat lamps. So the work was printing fine. But when they looked at it in their special booth designed to show the work most accurately, the red lights meant they were seeing it the least accurately.

A simple mistake. But one that had people seriously worried. And which could have been very costly.

Now, that problem could have been solved in a number of ways, I’m sure. But it seems to me that they did it the most sensible way: they went through every stage step-by-step and found that there was a genuine, rational issue (the wrong bulbs), which they then swapped for the right ones.

So if we’re going to be simplistic about it, this tool is a bit more left brain than some of the others. And by trialling both left-brain and right-brain approaches, you’ll get a wider range of solutions to choose between.

Action

INTERROGATE AND EXTRAPOLATE TOOLKIT

- Break the problem down into its constituent parts, smaller and smaller, more and more specific.

- Now establish which of those much smaller parts contain the problem and which are adequate (or even successful) as they are.

- Finally, extrapolate out: magnify those problematic elements. Are they faults you can fix in the same methodical, logical way you used to find them? Or do you now need to use another problem-solving tool on them?

Unless you’re really convinced that this tool is the one most likely to work, then I wouldn’t recommend starting with it. Because it’s the more logical approach, it could steer the group down very logical, rational tracks, which may make some of the other tools feel unnatural and difficult to work with afterwards.

But when you do use this tool, it has three simple and appropriately logical steps.

The first two steps

Break the problem down. Discuss it, examine it and write it out in a detailed step-by-step manner. Perhaps there’s someone in the group who is particularly good at teasing through the detail who could lead this action.

Then, interrogate each of those individual parts. Study them, discuss them, understand them and break them down further if needs be.

PROBLEM-SOLVING TIP

This tool can also be a trap. People can gravitate to it instead of the other tools which they find ‘airy fairy’, for one thing. For another, breaking down a problem into smaller parts and seeing which of those parts holds the problem (and therefore needs fixing) can lead to a rather ‘small’ solution. Which is fine, if a bit of correction is all that’s needed (like with the ‘meat lamp’). But it’s less likely to give you a big breakthrough unless you use it in conjunction with other tools.

Now it should be clear which elements hold the issues. It might just be a tiny detail of the process, a small aspect of an individual, a discrete advantage held by the competition.

The problem now feels more manageable. It’s not a big problem like, ‘The competition has a much better product’, it’s ‘The competition has a product which has these three features ours doesn’t have, features which appeal most to people aged 50–65’.

That kind of detail you only get from rigorous interrogation and it can be critical to how you solve the problem.

In the case I’ve just mentioned, you know just to add those three features. Or stop marketing to 50–65-year-olds. Or think of a new feature that appeals to 50–65-year-olds more than those three features would.

PROBLEM-SOLVING TIP

Say your problem was poor sales on your e-commerce site. Interrogating every tiny element, you might notice that your ‘cart’ button was labelled Buy now. Whereas other sites (moderately successful sites like Amazon, for instance) were using Add to basket. You might realise that Buy now sounds like more of a commitment than Add to basket, so some people are put off doing it. So you might change the name of that little button to Add to basket. (In testing, that seemingly trivial change has been found to increase sales by 10 per cent.)

Of course, traditional problem-solving models might start with an approach like interrogate and extrapolate: really studying every contributing element of the problem and analysing it. The issue I have with that is that you can quickly lose the holistic ‘let’s solve the big issue in one staggeringly impactful way’ view, because considering the problem in small pieces can encourage you to just tinker. It also takes up a lot of early energy and effort. That’s why I recommend you use the interrogative approach as a tool in its own right, rather than as an obligatory part of the set-up.

PROBLEM-SOLVING TIP

A ‘spider diagram’ (for a visual, look it up on the web … pardon the pun) can be a great way to explore a problem and break it down into components. At the centre you draw a circle containing the whole problem. Then, as you break it up, each part becomes a new circle (or node) off that centre one. As you break each of those parts into smaller elements, those become new nodes branching off the part they stem from; an ever-growing diagram of smaller and smaller pieces as you move away from the centre. If there’s a link between different nodes, you can draw a line to connect them.

The final step

Once you’ve interrogated the problem and identified the specific issue – the faulty parts, if you like – extrapolate the solution. In other words, discuss the fix, mentally put it in place and run through the scenario again, checking that having corrected those smaller issues, the whole thing works and the problem’s solved. It’s rather like the zany, evergreen board game Mouse Trap, if you know that. You fix the position of the diver so that when the marble hits the board he leaps up and lands in the tub rather than just missing it … and suddenly the whole operation works smoothly from start to finish. You trap the mouse and win the game.

Using this tool in a group session, with a mix of people who have different insights, levels of experience and a range of skills, can be really useful. You’re discussing the aspects of the problem in detail, and by breaking it down into discrete elements everyone can understand, an ‘outsider’ can come up with a way of fixing that one little cog that will get the whole machine working again.

Example

You’re on the motorway and there’s a sign. There’s been an accident and the middle and outside lanes of the road are going to close, 800 metres ahead.

So what do you do?

In England, you do one of two things. You either move into the slow lane straight away, becoming part of a huge, single-file queue.

Or you’re one of those self-centred, sociopathic so-and-sos who speeds down the empty lanes, past the long line of (impatiently) queuing traffic, then tries to force their way in at the last minute. Which the people who’ve been queuing in the slow lane don’t like, so they squeeze up, bumper to bumper to try and keep you out, increasing their risk of having a prang.

It’s stressful for both types of driver, and it’s a potential source of accidents.

Zip it

If you interrogate the flow of traffic, the data, the simple fact that while there are three lanes open it seems odd to have most of the traffic create an extra-long queue in one of them … you’d realise that there was a better way. That way being the late merge (or ‘zipper’ system), as used (by law) in countries like Germany and Austria.

There, you’re expected to keep using all the lanes. Instead of being frowned on for not joining the slow lane a.s.a.p., you stay where you are. Then, when you get to the point where the road actually closes, everybody adopts a ‘zipper’ approach. So if you’re in the slow lane, you let one car in the middle lane filter in. Then you go. Then the car behind you lets one in. And so on. Like a zip.

In fact, the zipper system doesn’t mean more cars get past the road closure in any given time – it doesn’t increase ‘throughput’. But it does reduce the length of the queue (it’s shorter because it’s wider) and it does reduce the difference in speed between the different lanes, which increases safety. And you’d imagine it reduces the stress levels of everyone involved too. Those in the slow lane don’t feel that cars in the other lanes are jumping the queue, while people in the other lanes don’t have to fret about trying to squeeze their way in, because they know they’ll be let in, like the alternating teeth of a zip.

PROBLEM-SOLVING TIP

You can also try making things worse. Take the problem you have and ask: what would make it a bigger problem? Exaggerate the issue, worsen the situation, downgrade the product/service. The group will relish this activity. Once you’ve done it, pause and then reverse the actions people suggested – and you may come up with new ways to lessen the problem. Strangely, people may find it easier to exaggerate a problem first, before they work out how to achieve the opposite.

Several tools in this book might have helped develop the same zipper solution. But interrogate and extrapolate would seem to be a good bet for it. It’s a logical problem, a matter of maths and physics – finding a way to maximise the available space on the road while creating a simple and fair system for drivers to deal with the obstacle.

It can work really well for you too. Just, as I say, don’t turn to it first every time, or you may find you get bogged down in too much detail too early. Because, to offer a conflicting point of view, as Malcolm Forbes (publisher of Forbes magazine) posits, ‘It’s so much easier to suggest solutions when you don’t know too much about the problem.’

Summary

Interrogate and extrapolate is generally more useful for solving problems than capitalising on opportunities. If you use it for innovating, it’s likely to give you incremental improvements rather than transformative ones.

It’s particular useful for problems that seem rational and where you have a lot of information and detail (since you can’t interrogate them if you aren’t able to find out lots and lots about them). Where there are lots of unknowns or things are vague or nebulous, you probably wouldn’t choose this tool first.

In fact, this tool is also often the tool we automatically use when confronted with a problem – but often rather half-heartedly. People just use the information they already have or know, or just do easy, lazy research.

So, to use interrogate and extrapolate successfully, ask:

- Are we being a modern-day Sherlock Holmes, gathering as much data as possible and analysing and understanding and debating everything we possibly can about it?

- Are we drilling down into enough detail? Are we breaking every part into its constituent parts, smaller and smaller, perhaps with a spider diagram?

- Can we find the real nub of the problem – the small part of parts which were hiding within the whole – and solve that, in a similarly logical, analytical way? Or do we now need another tool to solve it?