International Negotiating Styles

International negotiation is about strategies, tactics, cultures, and styles. While it isn’t true that each country has a specific negotiation style, there are some common aspects to the way people from the same country negotiate. Negotiation is a process composed of several steps and requires a lot of time to prepare before you arrive at the negotiating table. In this chapter, you will learn about the features of an international negotiation by walking through the whole process in integrating the cultural aspects.

The Negotiation Process

The most famous authors in the field of negotiation state that negotiation is a fact of life (Fisher and Ury 2011). It is a basic means of getting what you want from others. It is a back-and-forth communication designed to reach an agreement, when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed. People differ, and they use negotiation to handle their differences. In addition, some people will be easy to negotiate with and others will be difficult.

Here is the first aspect of negotiation that you should keep in mind. It is a systemic process composed of interdependent stages. Each stage must be consistent with the others to make sense and to be a real reflection of the negotiation strategy.

Negotiation is defined as a process by which two or more parties reach agreement on matters of common interest. All negotiations involve parties (people dealing with one another), issues (one or more matters to be resolved), alternatives (choices available to negotiators for each issue to be resolved), positions (defined response of the negotiator on a particular issue), and interest (underlying needs a negotiator has) (Cellich and Jain 2003).

Before getting to the core of the negotiation process, let’s talk about the negotiation dilemmas.

Negotiation Dilemmas

When designing their strategies, negotiators go through several questions, doubts, and hesitation. What should be done? How? When? And what if …? The so-called negotiation dilemmas make negotiators think about the actions they should take and the consequences of doing them. There are five main negotiation dilemmas.

The Honesty Dilemma

The honesty dilemma has to do with how much you should tell your counterpart about your intentions, possibilities, and constraints. It is also about the type and amount of information to share with them.

On the one hand, giving too much information can be threatening, as they can take advantage of you. On the other hand, withholding information can result in negative consequences. This can be perceived as a lack of honesty and transparency, and you will be seen as an untrustworthy negotiator. As a result, when preparing your negotiation strategy, you should determine the type and amount of information you want to put on the table and measure the consequences of that choice.

It is worth noting that honesty and transparency are not the same concept, and neither are they universal. Honesty relates to lies or not telling the truth. In some cultures, lying is defined as saying the opposite of the truth, whereas in other cultures, omitting information is lying. So if you are honest, you are supposed to tell the truth; if you are transparent, you are supposed to tell all the truth.

One recommended technique is triangulating the truth. That means you need to check the information that was given to you by several other means. One of them is to keep asking your counterpart questions that relate to the information you need, and look for consistency. The Chinese use this technique at each interaction. Another approach is looking for other sources of information, such as other people who work with them, their direct reports, their website, information from their industry, and so forth (Malhotra and Bazerman 2008).

You also should be able to pick up on nonverbal communication to see whether or not it confirms what was said. In addition, you should watch for responses that don’t answer your questions. Latin Americans often use this technique, either to avoid conflict or because they don’t know the answer to your question and want avoid losing face by admitting this. It is the technique of creating a diversion to avoid the topic. It can also happen that the response you get is true, but it just doesn’t answer your question. Ambiguity is part of the communication game in negotiation, and you need to be ready to cope with that. Finally, you can check reliability by asking questions about what you already know.

The Trust Dilemma

Without trust, you cannot do a deal. And trust is not given but earned. However, trust is not defined or built the same way in different cultures. In low-context cultures, for example, you earn trust from your counterparts by being objective, factual, and by not revisiting contract clauses once you have signed the document.

On the other hand, in high-context cultures, trust is dependent on people, and building relationships is the only way of earning it. Trust is needed for a negotiation to move forward, but you should measure how much trust you can have with someone, and how much you want them to feel they can trust you. Your counterparts will trust you if you are reliable. Reliability might be determined by your ability to tell the truth, be consistent and keep your promises.

Trust is a delicate thing. It requires a long time to build, yet you can blow it in a matter of minutes. All it takes is one incident of behaving inconsistently with what someone considers trustworthy behavior. It has to do with the relationship between pretrust—the belief that you will do what you say—and posttrust—the judgment about what you have done. If you go back on your word, you generate distrust (Blanchard 2013).

When you understand how your behaviors affect others, it’s much easier to gain respect, earn trust, and accomplish mutual goals. Keep in mind that people usually won’t tell you that they don’t trust you. You will need to deduce it based on their behavior.

The ABCD trust model is presented in Table 3.1 (Blanchard 2013).

Table 3.1 ABCD trust model

|

Able |

Believable |

Connected |

Dependable |

|

Demonstrate competence |

Act with integrity |

Care about others |

Maintain reliability |

|

Get quality results Resolve problems Develop skills Be good at what you do Get experience Use skills to assist others Be the best at what you do |

Keep confidences Admit when you are wrong Be honest Don’t talk behind back Be sincere Be nonjudgmental Show respect |

Listen well Praise others Show interest in others Share about yourself Work well with others Show empathy for others Ask for input |

Do what you say you will do Be timely Be responsive Be organized Be accountable Follow up Be consistent |

One of the most convincing ways of motivating someone to do something is to use strategies that lead to early trust, particularly among multiactive and reactive negotiators. Societies can be divided into high-trust and low-trust categories. Members of high-trust cultures are usually linear-active. They assume that people will follow the rules and will trust a person until that person proves untrustworthy. By contrast, members of low-trust cultural groups are often reactives or multiactives. They initially are suspicious, and you must prove to them that you are trustworthy (Lewis 2006).

Research recently conducted with 173 participants from 26 countries demonstrated that trust is not a universal concept, as people can come up with several different definitions of it (Karsaklian 2013). Table 3.2 presents some quotes to illustrate this statement.

Table 3.2 Definitions of trust

|

Definitions of trust |

Country |

|

Trust is the feeling that you can rely on other people. We need some time to trust people here. |

France |

|

We can’t easily trust someone, because people lie. People are very suspicious especially when it comes to money. No trust, money first. |

Cameroon |

|

It is a reliance on people’s integrity, surety, and strength of a person. People who correspond to your expectations. |

Morocco |

|

Trust goes along with reputation and recommendation. |

China |

|

It is what allows you to have meaningful relationships with other people. It is the belief that the other person has your best interest at heart. |

Canada |

|

Belief that one can rely on someone else. |

Sweden |

|

Trust is sincerity. Trust relates to honesty: we should not lie or deceive others. |

Japan |

|

Reliance on and confidence in the truth. Trust covers themes such as loyalty and fairness. |

Australia |

|

Trust, but verify |

Russia |

The Empathy Dilemma

A key factor about human interactions is that people tend to deny or project parts of themselves on other people. This means creating empathy is about building identification and avoiding denial. It is about demonstrating that you and your counterpart share something meaningful, so are able to walk together toward the fulfillment of your respective objectives.

Being empathetic is focusing on the feelings of the other person. It does not have to do with your emotions. Emotion is about your feelings; empathy is about the other party. If you are lucky and have a natural ability to empathize with people, you might get empathy quickly with your counterparts, thanks to shared values and some common ground. It will require less effort from both parties to feel a kind of belongingness and identification.

The Compete or Cooperate Dilemma

Negotiators who see negotiation as a competition have a hard time when their counterparts look for cooperation. Should you really choose one of them? Deals can hardly be totally cooperative, and one party may concede a bit more than the other one. Competition is inherent in negotiation but should not jeopardize the deal or the relationship. Cooperative competition is possible when negotiators establish objectives and rules together, so are connected by a process they both create.

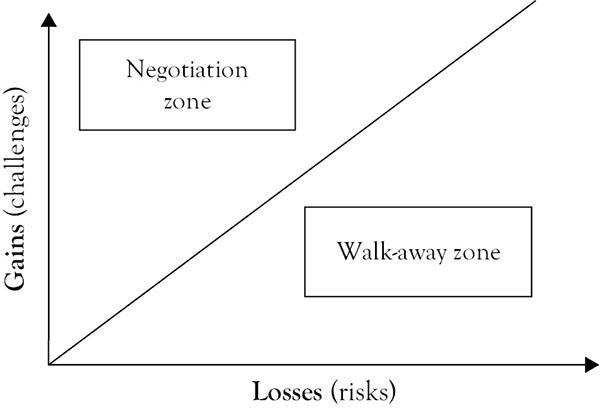

The Strategy or Opportunity Dilemma

You have carefully done your homework and your negotiation strategy is well-designed. You have tried to foresee unexpected situations and are ready to get down to business. But some unexpected opportunities occur as you negotiate, and you want to take advantage of them. Should you really do that? How much risk would you take by deviating from your well-established strategy? How can you measure these risks? Negotiating is about risk taking, but you need to be aware of the consequences of capitalizing on appealing opportunities as they arise. It can be a tempting siren song.

The Role of Emotions in International Negotiation

You might have an angry person before you. It can be a genuine anger or just a tactic to make you feel frightened or angry, too. Don’t try to stop them or to make them be reasonable at that moment. People who are feeling their emotions stop listening. If it is a genuine anger, people need to vent it. They will not hear a single word you say, as they are blinded by what upsets them. Let them say all they have to say. Once they calm down, you may start talking.

Take their anger seriously, and don’t try to minimize what seems to be a relevant issue to them. It would sound like a lack of respect—or worse—like mockery to people who are emotionally shaken.

It would be better to help them release their anger, frustration, and other negative emotions. People get psychological release through the simple process of recounting their grievances to an attentive audience. When they are mad and you tell them to calm down, you devalue them—which makes them more emotional and perhaps even angrier.

Instead, listen to and commiserate with them, and they will calm down by themselves. They want to be listened to as an emotional payment. Don’t avoid negative and stressful situations. Deal with them instead, if you don’t want to increase frustration on the other side. But you should avoid expressing an emotional reaction to it. The consequences can be disastrous if you lose your temper, because emotions make people unpredictable. You can control your emotions but not those from others.

When your thoughts are driven by negative emotions, you are more likely to be anxious, defensive, and view the negotiation as a conflicting, stressful situation. You will be ready to attack instead of compromise. Your reasoning will be more emotional than rational, and you will lose sight of your objectives and might make hasty, poor decisions. Thus, you will be more likely to give up as the negotiation gets tougher, and as your goals begin to look unattainable. It is pointed out that anger can blind, fear can paralyze, and guilt can weaken. You’d better ask for a break or change to another topic, so that you and your counterparts can return to rationality (Ury 2008).

Your thoughts lead to your perception of the negotiation. What you see is not the truth, but your perception of it. This can be either positive or negative, depending upon your state of mind. Some people see financial crisis as a terrible threat. Some others see it as an opportunity. Many companies do much better during tough periods than when everything seems easy for everybody.

It is when things are getting tougher that you need to be more creative. The Chinese understand it very well. The Chinese word for crisis is WeiJi. This word in composed of two words: Wei means danger and Ji means opportunity. Each risky situation holds valuable opportunities ready to be seized by the people who see them. These are the positive thinkers. They take the best spots in the market while others spend time and energy just complaining about how bad things are. Make sure that your thinking supports your actions rather than pulls you down to mediocrity.

Human beings are reaction machines. The most natural thing they do when confronted with a difficult situation is to react—to act without thinking. It is noted that there are three common reactions: striking back (attacking right back or attacking is the best defense), giving in (just to be done with it), and breaking off (abandoning the negotiation). You should not engage in any of them. That is why you need to take rationality as your guide throughout the whole negotiation process. Rationality enables you to have a distant view of close things (Ury 2007).

Mastering your thoughts is mastering your emotions. If you are rational, you are objective and able to get perspective on the opportunities rising before you. Being overcome by emotions will blind you to opportunities, as your mind will be busy thinking how miserable you are, how badly the negotiation is going, and how far away you are from attaining your goals. You will take every single action from your counterpart as a personal attack. As a result, you will increase the size of the problem instead of looking for solutions to it. No problem is permanent or impossible to overcome. Solutions exist, but you must be able to see and use them. However, being optimistic is not enough. You must be able to see problems from different perspectives to find solutions to them.

To do so, you should know what you want and your ability to obtain it. The triangulation between what you want to get, what you have to do, and what you are able to do will show you what you are negotiating for. The want-have-able matrix represented in Figure 3.1 enables you to measure the power of your wants (motivations), your duties (constraints), and your ability to succeed in your negotiations. Ask yourself specific questions about the negotiation you are going to conduct. Insert your answers in the model on a scale of 1 (does not apply at all) to 10 (totally applies). Place a dot in the corresponding degree of the scale in each one of the three dimensions, and then connect them with a line. You will see in which sides the cloud is bigger and thus, more influential in your negotiation.

Figure 3.1 The want-have-able matrix

Source: Adapted from Krogerus and Tschäppeler (2011).

You are always in control of what your mind should focus on. To stay focused, your mind needs to be sure that you know where you are going. This clarity on your ideas and thoughts will prevent you from getting distracted with other factors that might naturally intervene, or be introduced by your counterpart. It will also avoid the periods of inactivity from your counterpart. If your counterparts use emotions just as a tactic to destabilize you, don’t fall in that trap. Let them play their game. Keep your temper and carry on objectively. This is the best way of neutralizing their tactic. They will understand this does not work with you and will give up on it.

One of the worst feelings negotiators have is to feel stuck in the same stage of the negotiation. You need to know how and when to take action. You must make the negotiation evolve at each step. However, this evolution does not always rely on concessions, deals, or contracts. It can also be about building relationships, getting more information, getting more involved in your counterpart’s life and building trust. Whatever it is, make sure that you are getting something worthwhile from each encounter. To do so, you need to understand the value of the intangible.

You are already wondering which types of cultures are more likely to use emotions in negotiation. You won’t be surprised that multiactive and affective cultures use them. It’s an easy way to lead people to do what they would not have done without this kind of emotional pressure. It might work very well when you know how to use it. However, the consequences can also be dramatic when the other side expresses regrets when it later understands that you have manipulated them. This may not be seen as fair play. Be very careful about using and facing emotions during negotiations, because they reduce information-processing abilities, which are critical in negotiation, and destabilize the situation. Use creativity instead of emotions.

Creativity is a key activity in international negotiation. It has been stated that creativity is the consideration of a wide variety of alternatives and criteria and the building of novel and useful ideas that were not originally part of the consideration set (Stahl et al. 2009). Because cultural differences are associated with differences in mental models, modes of perception, and approaches to problems, they are likely to provide strong inputs for creativity. If you are able to list new and old ideas by comparing them, the next step is to place them in the thinking outside the box model between chaos and order. You will then see the emergence of new and viable solutions, as represented in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 The thinking outside the box model

Source: Adapted from Krogerus and Tschäppeler (2011).

The Role of Attitudes in International Negotiation

Negotiators can be in different states of mind, such as happy, sad, depressed, puzzled, and so forth. Among these, he identifies four typical negotiating attitudes (Rich 2013):

•Fusing: This is the one who wants to combine the agendas of both sides to create a common currency for each participant. Fusers bring a positive, confident, and optimistic attitude to the negotiating table, without being intent on putting one over on the other side.

•Using: These people take advantage of the other side. They may bring confidence and self-confidence to the negotiation, but this comes at the expense of the other side’s state of mind. They may be assertive and uncooperative, focusing on their own needs and not caring about their counterparts.

•Losing: Losers come to the negotiation with a defeatist attitude. Often this happens to satisfy the concerns of others.

•Confusing: These people labor under mistaken assumptions, misapprehensions, or prejudices, which may cause them to be losers or users.

Independent of their attitudes, never neglect your counterparts’ problems. Their problems are your problems, because these can get in the way of the agreement you want. Listening to their problems and helping them to resolve these will move your negotiation forward more quickly, and you will be viewed favorably and appreciated by your counterparts.

Listening is the least expensive—and most valuable—concession you can make. We can say that you will have some credit to use with them after that. And, if you are unable to come up with a solution, you can bring more people to the negotiation who would (1) help them with their problems and (2) be your allies for the rest of the process. Your help will add to their well-being and they will be grateful. Do them a favor and they will owe you one.

From Preparation to Closing

If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.

—Benjamin Franklin

You will go nowhere without a well-prepared negotiation. Preparation should take at least 70 percent of the time you allocate to your negotiation process altogether. This includes a number of steps:

•Get extensive information about your counterpart’s company, market, and competitors.

•Analyze all alternatives—besides your offer—that your counterpart would have to satisfy the same needs.

•Know your company, products, market, and competitors very well. It is embarrassing when you learn about your own market from your counterpart. You look unprofessional and unreliable.

•Know about the people you are likely to interact with: their positions within the company, their reputation, their relationships with one another, their preferences, and dislikes.

•Know about your culture and the related stereotypes.

•Know about your counterpart’s culture and create your own do and don’t list.

•Establish your goals by creating your BATNA, your reservation price, and your potential ZOPA.

•List all the concessions you would be able to make and the ones you would find unacceptable.

•List all the concessions you expect your counterpart to make and the arguments you could use to persuade them to give you what you need.

•Choose your negotiation style and design your negotiation strategy.

Try to envision the whole negotiation process when you start preparing it. Think about the information you must have, the way you will use it, what your goals are, the strategies, and tactics you will need. Also consider concessions, closure, follow-up, and possible renegotiations. Think about the whole process, and then work backward. In other words, establish what you want to get and work through everything you need to get it. You can also draft an agreement and follow it to make sure that you are not forgetting anything important.

An effective way of having a good overview of your counterpart’s business environment is performing a Porter’s analysis. The five forces theory to industry structure was developed to help companies survive in a competitive environment. The five forces are (1) the threat of substitutes, (2) the threat of new entrants, (3) the bargaining power of suppliers, (4) the bargaining power of clients, and (5) the intensity of rivalry among competitors, as illustrated by Figure 3.3 (Porter 1980).

Figure 3.3 Porter’s five forces model

You can fill in the bubbles with the information you get from your counterpart’s market. Insert their competitors in the rivalry bubble in the center of the model and you will understand the types of pressure they face. Then list their suppliers and their clients, including you. The more companies you list on each side, the more bargaining power your counterpart has, and vice versa. Finally, assess the barriers to entry by identifying the potential competitors likely to enter the same market, and the alternative products your counterpart might have to satisfy the same types of needs. What your company offers also can be among the alternative products. This analysis of your counterparts’ competitive situation enables you to identify their BATNA, and anticipate their objections to your arguments, which will be extremely useful to you in your negotiation.

In addition, surprise your counterparts by showing how much of their market you know, but avoid any sign of arrogance. You are not there to tell them about their job, but to help them to do it better. Never rely totally on their brief about their market, because it can be misleading for two main reasons. First, they might not disclose some relevant information because they believe it is proprietary. Second, they might have an incomplete or inaccurate perception of their own market.

Know the Market Better Than Your Counterpart

Consider the following situation. A director of an international company asks you to make a presentation to his clients over a lunch he organizes for his clients’ enjoyment. Because there are a couple of topics you can speak to, you ask him to pick the most appropriate one for his clients. He chooses international negotiation. As an international negotiator, you are happy with that. You prepare your 30-minute presentation and fly to his country for that meeting. Nothing can go wrong, because you have mastered your topic, and the company’s director knows his audience very well, as he organizes these events quarterly with different speakers.

Upon your arrival, he asks you to cut some of your slides to allow more time for questions. You would rather not do it. You know the reasons for creating those slides, but again, you think, “He knows his audience and this is the first time we are working together.” Then you make your first concession by deleting the slides.

You give your presentation. Despite your enthusiasm and knowledge, the audience is attentive but there is little interaction. You finish early because there are not many questions from the floor. Why? They were mostly HR managers and not negotiators. Although they found it interesting, the topic wasn’t connected with their day-to-day work life.

You realize you should have talked about other topics that you know well, such as intercultural management (which was among the topics you offered to your client and he did not pick). But should you show him that he has made a bad decision? Does he realize that he committed a strategic error in choosing the wrong topic? No, he does not. He would rather say that people would not have come if they weren’t interested in the topic. Would you agree? And what if people would have come just for the networking, independently of the topic?

At the end of the day, everybody is disappointed. The participants would have rather attended a speech about something closer to their daily work lives. Your host, who paid for your trip, would have preferred to make his clients happy. And you, who had spent a lot of time preparing and traveling to deliver a presentation on a topic you have mastered, would have liked a more receptive audience.

Now that you have this experience, you know that: (1) you always need to check the information you are given, because often people say that they know more about something than they do; (2) in your follow-up, when you get back home, you already suggest some alternative ways of working together next time; and (3) he owes you a concession, and next time you work with him, he will be more willing to consider your advice.

Take your time to perform a Porter’s analysis for your own company to have a better overview of your own competitive situation, too. But make sure that you see the markets as they are, that is, across physical boundaries. You are working in an international environment, so your analysis must not be bound to one country. Analyze all the possible alternatives of being part of your counterparts’ competitive world, and not only his local market. The same applies to your company. If you focus on local competitors, suppliers, clients, potential entrants, and product alternatives, your analysis will be misleading. It will take you away from reality through a phenomenon called myopia.

Beware of Myopia That Can Lead to Negotiation Errors

Myopia is also an illness negotiators suffer from by being self-centered. Their preparation focuses only on how to persuade their counterpart to buy their product. Or, for the purchaser, how to make the seller accept their terms for the negotiations. People rarely take time to see beyond themselves. They don’t know much about the other side, which is a paradox, because they will need the other side’s participation to reach their goals.

This illustrates that preparing your negotiation is defending yourself against losing sight of your negotiation goals. The most common negotiation errors are the following (Cellich and Jain 2003):

•Unclear objectives

•Inadequate knowledge of the other party’s goals

•An incorrect view of other party as an opponent

•Insufficient attention to the other party’s concerns

•Lack of understanding of the other party’s decision-making process

•No strategy for making concessions

•Too few alternatives and options prepared in advance

•Failure to take into account the competition factor

•Unskillful use of negotiation power

•Hasty calculations and decision making

•A poor sense of timing for closing the negotiations

•Poor listening habits

•Aiming too low

•Failure to create added value

•Not enough time

•Uncomfortable negotiations

•Overemphasizing the importance of price

Prepare Your Negotiation

The preparation stage of any negotiation is often overlooked, as people feel that they are too busy to invest time thinking about the deal in advance. Negotiators often are so sure that their strategy will work as well abroad as it has at home that they just take a few minutes to coordinate with the team members on the plane. This is also the moment when they read some tourist guides to learn a bit about the counterpart’s culture before landing.

You understand that this is a very unrealistic and risky approach to international negotiation. When you are seriously preparing your negotiation strategy, start by asking yourself these questions:

•Who will be part of your team? Who should be part of your team? Do you need any experts? Which type of attitude do you want your team to bring to the negotiation?

•What roles are your team members going to play? Who is authorized to make concessions?

•Do you need any materials prepared in advance? Should you send some materials to the other side in advance?

•Where is the negotiation going to take place? Will you make presentations? How long should they take?

•Who is on the other team and how do they work? What do you know about them? Where did your information come from?

•Is there any history between your company and your counterparts’?

•What agenda will you create and how are you going to share it with your counterparts?

•What should you and your teammates know about your counterparts’ culture?

You should make sure that you have all the needed people, each one with their specific competences and roles as negotiators. But other people than negotiators might intervene in some moment as experts. For example, engineers and lawyers are not trained to be business negotiators but their expertise is often needed in moments when the topics put on the table of negotiations become more technical.

In more deal-based cultures like the United States, negotiators talk about contracts from the beginning and to do so they take their lawyers to the table of negotiation at the very first round. This approach might be efficient when dealing with other contract-oriented cultures. However, it is not appreciated in relationship-based cultures. In these cultures, contracts and agreements are the last topic that negotiators talk about and it looks aggressive to bring attorneys from the start. It is perceived as a lack of trust in your counterparts and as if you were a contract hunter with no interest in building human relationship.

It is recommended that negotiators have a devil’s advocate. This person’s job is to criticize your decisions and find faults in your logic (Malhotra and Bazerman 2008). You will often miss some points in your strategy because it is your strategy. Even if you step back and try to get an objective look at your strategy, it is still your creation. Someone else, who is not involved in it, will have a different perception of it. The devil’s advocate is not only useful for finding errors in what you have done, but also may highlight and confirm positive aspects of your strategy. Basically, you need a trustworthy, neutral person reviewing your strategy as an outsider to bring more clarity to it, thanks to an unbiased judgment.

Establish Your Goals

You need to feel that you are in control of yourself to be in control of the negotiation. If you have a clear idea of what you want and where you are going, you will feel much more confident. Make sure that you have listed everything that has to do with your negotiation, so you do not forget.

When you are writing down your negotiation strategy, first establish the different levels of goals you want to reach, and the factors influencing them—both positively and negatively. Then divide the factors into the ones you can control and the ones you can’t. It’s not worth spending time and energy trying to change what you cannot control. This will increase frustration and anxiety. You would be better served by focusing on the important items that you can control. Then you are able to make a difference.

You can even depict goals and factors in a situation and give them the needed importance as your negotiation evolves. Next to each controllable factor, write how and why you can use it. Next to every uncontrollable factor, write how you will deal with it. Give your scheme the shape you like. See the previous Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Example of goals and controllable and uncontrollable factors

|

Goals |

Stage of the negotiation |

Controllable factors and degree of influence |

Uncontrollable factors and degree of influence |

Your reaction to factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legend: ♦♦♦ crucial, ♦♦ strongly influential, ♦ influential, ◊ neutral, ◊◊ not influential

Making it clear what the negotiation is for will help you to persevere and overcome obstacles, because you are well prepared and know where you are going. Persistence is a key factor for your success. You need to be linear and objective to get what you want. But first you need to make sure that you are heading to the right place. Remember that efficiency is doing the right things, while effectiveness is doing things right.

Goals are the focus that drives a negotiation strategy (Lewiki et al. 2011). Determining the negotiation goals is the very first step in developing and executing a negotiation strategy. Then they can focus on how to achieve those goals. There are several types of goals negotiators may aim for: substantive goals (money), intangible goals (building relationships), and procedural goals (shaping the agenda).

Effective preparation for a negotiation includes listing all goals negotiators wish to achieve, prioritizing them, identifying potential multigoal packages, and evaluating possible trade-offs among multiple goals. The authors make it clear that wishes are not goals, and that your goals are often linked to the other party’s goals. Effective goals must be concrete, specific, and measurable.

You should use a great deal of rigor to establish your goals. The Table of the Right Goal will help you to do that by using the smart/pure/clean attributes of your goals, as presented in Table 3.4.

Table 3.4 The table of right goals

|

S |

Specific |

The right goal |

C |

Challenging |

|

|

M |

Measurable |

P |

Positively stated |

L |

Legal |

|

A |

Attainable |

U |

Understood |

E |

Environmentally sound |

|

R |

Realistic |

R |

Relevant |

A |

Agreed |

|

T |

Time phased |

E |

Ethical |

R |

Recorded |

Source: Adapted from Krogerus and Tschäppeler (2011).

Let’s assume that you are negotiating the quantities of products with a purchaser. Table 3.5 is an example of how to establish your goals for that round.

Table 3.5 Example of goals you could have when using the table of the right goal

|

S |

Quantities |

The right goal |

C |

This is the first time we are working with these figures |

|

|

M |

Number of products |

P |

I suggest that you order # products |

L |

We have observed the legal aspects of our deal |

|

A |

Possible to produce |

U |

I understand that this quantity is appropriate to your needs |

E |

All parties will benefit from that |

|

R |

Possible to deliver by the deadline |

R |

This quantity will allow you to benefit from % discount |

A |

We have a formal agreement |

|

T |

In days/weeks/months |

E |

I am giving you the best cost-efficiency ratio |

R |

We have a contract and we follow up |

Use the goals portfolio matrix represented in Figure 3.4 to monitor the evolution of your negotiation toward achieving your goals. Establish your timeframe. Be realistic when doing this: it’s not when you want it to happen, but how long it can really take to get you where you want to go, factoring in your counterpart’s behavior. After each negotiation round, take your goals portfolio matrix and write down what you have achieved. First you need to list your goals, and then place them on the matrix. Some examples of goals in international negotiation are presented here.

Figure 3.4 The goals portfolio matrix

Source: Adapted from Krogerus and Tschäppeler (2011).

List Your Goals and Then Place Them on the Matrix

1. Socializing

2. Getting to an agreement

3. Price figures

4. Delivery terms

5. Quantities

6. Gathering information

Here is an idea to consider. Sometimes, achieving the goal you have written down won’t be the most important or rewarding part of a negotiation. Often it’s the journey that matters. You walk side-by-side with your counterpart. If you don’t reach your initial goals at some stage, you still need to be happy about the journey. In many cases, the journey itself should be your goal. It has to do with building relationships, earning trust, and gathering information. What can look like a waste of time in the short term can end up being the best way of succeeding a negotiation in the long term.

If you have not achieved what you wanted in some round of negotiations, that doesn’t mean you failed. It can mean that your goal was not consistent with that particular stage of your negotiation, and that you needed more time and information to reach it. This also may mean that you will need to review some of your goals to make them more realistic and coherent with this stage of the negotiation process.

In other words, establishing negotiation goals is not enough. They should be realistic and attainable, and you should try to reach them—however you can get there. Sometimes it may take longer; sometimes it may go fast. This depends on several factors, such as the compatibility with your counterpart’s goals, the evolution of the negotiation, your own and your counterpart’s willingness to work together, and so forth.

Establish Your Strategy

In some situations, you will feel you are in a weak negotiating position. There is a common belief that sellers are always in a weaker position, as purchasers hold the power. As a purchaser from a French company once said, “We have our requirements and it is their (suppliers’) job to take them into account.” Sellers often forget to consider the switching costs to the buyer, and the intangible value of what they offer. They feel weaker because they are trapped in the price negotiation.

You can overcome this by leveraging your counterpart’s weaknesses. It will be much easier for you to deal with the balance of power when you develop a SWOT analysis and are clearly aware of the strengths and weaknesses of all parties. Another way to minimize your weaknesses and to increase your strengths is building coalitions with other people who will bring the resources you are missing.

The SWOT analysis is based on a Stanford University study from the 1960s. This analyzed data from Fortune 500 companies and found a 35 percent discrepancy between the companies’ objectives and what was actually implemented. The reasons for the difference were that the objectives were too ambiguous and that many employees were unaware of their own capabilities. Today, the SWOT analysis is an important tool for every person who needs to have a clear overview of the positive and negative aspects of their activities.

SWOT stands for strengths weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. It includes both internal and external factors. The strengths and weaknesses are internal factors that depend on the company’s strategy and are totally controlled by it. They actually are consequences of the company’s strategic choices. In contrast, the opportunities and threats are general tendencies generated by the market itself, over which companies have no control.

The strategic decisions based on a SWOT analysis aim at leading the company toward leveraging its strengths for taking market opportunities and reducing its weaknesses, to be protected from market threats. As for the Porter’s analysis, don’t forget that the markets you are analyzing are not limited by geographical boundaries. Table 3.6 depicts some potential aspects of your offer that you can include when performing a SWOT analysis.

Table 3.6 SWOT analysis

|

Your offer |

|||

|

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

Opportunities |

Threats |

|

• Compatible with your client’s needs • Uniqueness • Quality • Brand name • Company’s reputation |

• Obsolete technology • Lack of accuracy |

• Legislation • Consumption habits |

• Competition • Financial crisis |

The SWOT analysis can be used in several levels: for the company as a whole, one business unit, one line of products, one product, or even one person. Perform a SWOT analysis for yourself as a negotiator. Writing down your strengths and weaknesses will give you a clear overview of your abilities. Use Table 3.7 as an example.

Table 3.7 Your personal SWOT analysis

|

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

Languages you can speak Ability to create empathy Cultural awareness Open-mindedness Technical skills |

Fears Lack of cultural knowledge Lack of autonomy |

Now focus on your strengths. If this comes naturally to you, then you are more likely to be confident, positive, and enjoyable. Use your strengths to leverage your actions as a negotiator and make a difference. In order to fully use them, you must be aware of them. More often than not, people are not conscious of their own strengths and weaknesses, and that is why they cannot identify opportunities and threats. Your strengths are your best assets, and you should rely on them. In addition, they will make you feel more motivated, and you will take negotiation as an enriching human interaction instead of the common classical perception: that it is stressful and confrontational.

When you believe you have done enough preparation, spare some time to rehearse. This may sound useless, or silly, or even appropriate only for junior negotiators. Think again. You will never know how long a presentation will take without rehearsing it, and you don’t know how well your team will perform without putting it in a real-life negotiation situation. In addition, when you rehearse, you may think of some reactions from your counterpart that otherwise might not have occurred to you. As a result, you will look and be much more confident.

Meet Your Counterparts

Now that your preparation is done, you are ready to meet your counterpart. This is the so-called moment of truth. Whatever their culture, spend some time bonding with them. Try to find any common ground that could help you to empathize with them. Start building trust by showing that you have something to share. Build relationships by showing who you are, but avoid actions that could be interpreted as arrogant.

Negotiation is not just a technical problem-solving exercise. It’s a political process in which different parties must participate and craft an agreement together. The process is just as important as the product (Ury 2007).

Negotiators come to the table because they need something from the other side. Your role is to create a favorable environment for both of you to work together and be productive. It’s imperative that both sides feel comfortable and are in good spirits before getting started. Linear negotiators are just starting to understand and value what multiactives and reactives recognized thousands of years ago: investing in good long-term relationship.

There are several things to prepare before meeting your counterparts.

Agenda

The agenda for each meeting establishes what topics will be discussed, and in what order. You should reconcile your agenda with the one from your counterpart by making sure that critical issues are addressed. By doing so, the parties strengthen their confidence in each other. They are equally involved in decisions about the agenda, instead of one of them imposing it on the other. One important criterion to decide is the order of difficulty. Some negotiators might start with the easy topics to create a pleasant beginning and leave the tougher ones to the end. Others would rather get rid of the most complex issues at first and then move smoothly to easiest ones.

However, deciding on the contents and the order of the topics doesn’t mean much in different cultures. Polychronic cultures have a more holistic view of the issues and will move back and forth across the subjects in the agenda. Moreover, what might be seen as peripheral in some cultures can be viewed as pivotal in others.

For example, Chinese negotiators find it relevant to present the history of the company and its founders’ values, because the whole company draws on these values. If you are not patient enough to listen to that, you will not only be perceived as rude, but will also miss valuable information that will be extremely useful to you later in the negotiation. Establish an agenda that will lead you to your goals. Start the meeting with pleasant subjects, and create a collaborative feeling and atmosphere.

Some people confuse pleasant with humorous, and might start a meeting by telling jokes. This is a tricky way of breaking the ice. Humor doesn’t travel well. You never know how jokes will be interpreted. If your joke requires translation, that will take all the fun out of it. In addition, some jokes are ironic or use stereotypes that your counterparts may perceive as humiliating or inappropriate. And how embarrassing is it when you tell a joke and your counterparts keep looking inexpressively at you? Instead of creating a pleasant environment, you are more likely to make everybody feel uncomfortable.

A classic example is the story of an American giving a speech in Japan. He is happy to see his audience nodding at everything he says, as the interpreter translates his words. He decides to close his speech with a joke. Before he has finished telling it, all the floor bursts into laughter. He is flattered and amazed and can’t help going to see the interpreter to congratulate him. “You are so skilled,” he says. “I know that translating jokes is not easy. You did it so well that people were laughing even before I finished!” “Thank you,” replies the interpreter. “It is very nice of you to congratulate me. But you should know that I did not translate anything. I just told the audience that our guest was going to tell a joke and that it would be polite to laugh.”

Establishing a good working environment is not only necessary to get agreements, but also to get through disagreements. The best time to lay the foundation for a good relationship is before a problem arises. This allows you to create a more favorable environment to present your counterarguments and objections, without being aggressive (Ury 2007).

People should be receptive to what you say. But if the atmosphere is already tense, then every disagreement sounds aggressive, and counterparts are more likely to defend themselves than to listen to the other side and try to find solutions together. Don’t attempt to separate substance and relationship, because this is not how people’s minds work. What you say has more to do with you than with what you sell or buy.

Gather Information

While you are talking with your counterparts, try to gather relevant information that would be useful for you during the negotiation. Establish dialogue that allows each of you to ask questions and get answers directly from each other. Negotiation is more about asking than it is about telling. For instance, you may ask how they have been satisfying the need you are supposed to address, about their plans for expansion, the countries they envision reaching, and the ways they will do it (direct investment, alliances, etc.).

To make sure you get the information you need from your counterparts, first prepare a favorable environment for them to talk. Spend as much time as needed to socialize and get to know them. Let them get to know you, too. This phase of the negotiation is important, because it is also when you start creating empathy and building trust. You cannot work with someone who is a complete enigma to you. In addition, people don’t give concessions to people they don’t know. You can’t make a request or present a proposal to someone with whom you have not established any kind of human relationship. Listen actively and acknowledge what was said. Everybody has a deep need to be understood.

Expressing agreement with the other side does not mean suppressing your differences. If you address these openly, it shows the other side that you understand their perspective, and they will welcome your arguments after that. Ury suggests that your counterpart will be positively surprised and might think, “This person actually seems to understand and appreciate my problem. Since almost no one else does, that means this person must be intelligent” (Ury 2007, 73). Then you have opened the door to show that you are, indeed, an intelligent international negotiator.

But realize that the other side will be aiming at gathering information from you as well. One traditional question when you are negotiating abroad is about how long you will stay in the country. Although it might sound just like a courtesy or curiosity question, it might represent important information for their strategy. In several relationship-oriented cultures, negotiators like to drag the other side out until their departure date by avoiding getting down to the core topics all over the time you spend there. They will wait until you are hurried to make you an offer that you might accept just not to go back home empty-handed.

Meeting Site

Decisions about the place to meet for the negotiation are strategic. Doing this on the home turf gives that negotiator a territorial advantage. It is psychologically more comfortable, practical for getting people involved, and gathering additional information—not to mention less costly.

If the meeting takes place in your country, you are responsible for making your counterpart’s stay enjoyable. Think about their well-being in terms of accommodation, food, and visits. People who travel often need to feel comfortable when they are abroad. A bad night might put them in a very bad disposition to work the next day. The more you look after your counterparts, the better spirits you will put them in to work with you. In addition, they will feel valued and grateful and willing to reciprocate in some way.

Many people believe that negotiating in their counterparts’ country puts them in a weaker position. This assumption has not proven true. Negotiating at your counterpart’s place has several positive aspects, too. First, you may visit the facilities and verify statements they might make during the negotiation. Second, you can meet relevant people in addition to the negotiators, and you can get a sense of the company’s atmosphere. Finally, because you invested in a trip, you made the very first concession. Your counterpart already owes you one.

However, there are some logistic aspects that you can’t master if you negotiate at your counterpart’s location. For example, if you need to make a PowerPoint presentation, ask your counterparts if they would agree for you to make a quick presentation at the beginning of your meeting. Follow-up to make sure that the equipment will be available, or bring your own. Don’t forget to include that in the agenda.

Wherever the encounter takes place, be sure that there will be social events associated with work. Few negotiations are effectively conducted in meeting rooms and offices. Lunches, dinners, trips, shows, and karaoke are part of the whole process. Each culture has its own traditions, and you need to be ready to go along with them.

Your counterparts expect you to be an agreeable person, interesting to talk with about other topics beyond work. You should have some general knowledge and be able to discuss different subjects with different people. Nothing is more boring and disappointing than taking someone to a nice place to relax only to have them keep talking about work and deals. Your counterparts also want to know if they can have fun with you and spend pleasant time together. This can really make a difference when they are deciding between working with you or someone else.

You might argue that socializing does not look professional. But remember: negotiation is a human interaction more than anything else. It is imperative that your counterparts appreciate your human side. The more comfortable they feel, the more positive they will be about you and your business. Some negotiators do exactly the opposite. They want to make the other side feel uncomfortable, under pressure, and weak in order to take advantage of them. As an intelligent international negotiator, you want to take your counterparts to the negotiating table, not to a battleground.

Schedule

The time allocated to discuss each topic, as well as for breaks, does not mean much in several cultures. Time pressure is not always productive. The amount of time depends on how many people participate in the negotiation and also on the questions. Be structured with linear-active counterparts, and flexible with multiactive and reactives. In any case, always be punctual. If possible, arrive early to check the meeting room and its facilities.

Now is the moment when you will use your list of concessions and demands. You and your counterpart will try to get what you both had planned during the preparation phase. There will be arguments and counterarguments. Depending on your counterpart’s culture, this phase may be more or less time-consuming and might require a few or several rounds.

Master the Bargaining Phase

You know that it is impossible to reach any deal alone. Negotiation is a collective activity. There should be at least two parties to create a deal. The other parties have to be as involved in the process as you, if you want to work toward a deal. You have strings linking you to your counterpart. If each one of you pulls too hard, the string is more likely to break and both will be left with nothing. The classic image of the two donkeys linked by ropes and wanting to eat on their own sides at the same time is a good illustration of a negotiation, as represented in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5 The donkeys and the food

Concessions and Reciprocating

Negotiators are often reluctant to make concessions because they think that is a sign of weakness. They believe that if you give a hand, next time they will ask you for the whole arm. This makes them afraid of not being in control of escalation. So when they make one concession, they expect their counterparts to immediately reciprocate. But there is a value attached to each concession.

If you want your counterpart to understand what a concession means to you—and what it should mean to them—then you need to label it. People tend to undervalue or ignore the concessions of others just to escape the obligation to reciprocate. Instead of simply giving something away, you should make it clear that your action has a cost to you, whether monetary or nonmonetary. Then it becomes embarrassing to your counterpart to justify nonreciprocity (Malhotra and Bazerman 2008).

However, make sure that all parties understand what reciprocating is supposed to mean. Even if the other side acknowledges your concession, they might still try to reciprocate with something of lower value. Your job is to eliminate all sources of ambiguity and state the level of reciprocity you expect. It is recommended that negotiators make contingent concessions, that is, that you explicitly tie your concessions to specific actions by the other party. Although this strategy may guaranty balanced concessions in your negotiation, it might reduce your opportunities for building trust, and developing and strengthening your relationship with your counterparts. They should be used at the right moment and for the right reasons. Do not overuse them.

Negotiation helps to create value through agreements that make both parties better off than they were before. Sometimes what you want to earn from a negotiation is not vital to you. You could keep going alone, but it makes you better if you work together with a counterpart because this enhances performance and quality.

The Importance × Strategy Matrix represented in Figure 3.6 will help you to assess the value of each concession you might be able to make during your negotiations. There is a cell in which you will place every aspect of your negotiation that is not negotiable, because it is highly important and strategic. Very high-value concessions should be traded with other highly valuable concessions from your counterpart. The same is true for high-value concessions. Finally, you can play with the low-value concessions by using them at opportune moments throughout your negotiation.

Figure 3.6 The importance × strategy matrix

Introducing New Ideas

If you are conducting your negotiation the way you wish—based on dialogue and mutual understanding—a new proposition should not come as a surprise. This will flow from the work you have been doing with your counterpart so far. The more what you present dovetails with your counterparts’ interests, the easier it is to introduce new ideas.

Sometimes, it can be tough to convince the other side about the value of the alternative you are proposing. Remember that novelty can be frightening. People tend to stick to their well-known references and often are reluctant to change their habits and accept something that is totally new to them. They might argue that “we have never done it before,” or “we have always done it this way.”

Cultures with a high uncertainty avoidance index are the most reluctant about and suspicious of new ideas and about working with new people, too. Your job is to reassure them and make it easier for them to accept your new ideas by walking side-by-side with them throughout the process. But first they need to trust you. No other type of guarantee can replace the trust they have in you.

A very efficient way to get people to accept new ideas is to make them think they thought of them, as the French novelist Alphonse Daudet said in the nineteenth century: “La meilleure façon d’imposer une idée aux autres, c’est de leur faire croire qu’elle vient d’eux” (The best way to impose an idea to others is to make them believe it comes from them). This allows you to open the way for your counterparts to come up with an idea that matches the point you wanted to convince them about. Once they select an alternative, it becomes their idea.

The fact that we better accept our own ideas aligns with a well-known issue in international business, called the not invented here (NIH) syndrome. The NIH syndrome prevents people from buying imported products because they want to support local businesses, or because they don’t trust the quality of foreign products. On the management level, the NIH syndrome creates tension between headquarters and local subsidiaries, because the local managers are reluctant to implement the decisions made by the headquarters without being able to adapt them to their particular market. Some intercompany negotiations happen because of the NIH syndrome, which end up having considerable impact on the company’s international marketing strategies.

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) matrix can help you make it easier to have your new suggestions accepted by your counterparts. This tool was developed at the BCG in the 1970s to assess the value of the investments in a company’s portfolio. Each of the four cells has a specific name, based on the level of market growth and relative market share.

The items in each cell also can fall into four categories. The question marks have high growth potential but a low relative market share, because they represent new products, ideas, and concepts in a market. These need considerable financial support to develop awareness and value. The stars have a high market share and a high growth rate, but still require a lot of effort to become profitable and enjoy customers’ support. The cash cows are former stars that benefit from customer preference and loyalty. They are the most profitable products for the company. Finally, the dogs have a low share in a saturated market and should not be kept in the long-term portfolio. The BCG box relates to the product life cycle with its four stages: launch (question mark), development (star), maturity (cash cow), and decline (dog).

You may use the same model, in Figure 3.7, for your new suggestions and arguments, since they have a limited lifespan, too. First, you present your new argument and face your counterpart’s hesitation about accepting a novel idea. Then you prove its value for you both, search for their support, and ask for their agreement. Showing how your argument is valuable and unavoidable will create a need to the other side, and lead to acceptance. Finally, do not waste time and energy trying to convince your counterpart about the value of old arguments, which have already proven inefficient and no longer persuasive.

Figure 3.7 The BCG matrix or the arguments’ life cycle

The BCG box enables you to introduce your arguments step-by-step. People are frightened when you present something that is perceived as being too big, too different, too fast, and too hard to achieve. Too much and too fast always sounds overwhelming. By taking an incremental approach, you walk your counterpart through the whole process by anchoring each step. This reduces the distance between each anchor and the next, because big steps look much more risky.

To convince your counterparts about the value of your arguments, tell them what they wish to hear. Some facts and arguments can be presented differently, according to the needs of the people across from you. It is a matter of perception, which is, by the way, based on their personal values. For example, if you take Schwartz’s model as an indicator, you will want to use a slower paced and reassuring approach with conservatives, while underscoring innovativeness to those who are open to change. You also should talk about how much your counterparts will gain by adopting your new arguments to self-enhancement-oriented people, or how much everyone would profit from the new idea to any self-transcendent people.

Dealing With Disagreements

Sometimes you will feel that bargaining is tougher, and you see that you are heading toward disagreement. Then you need to bring up potential losses instead of potential gains. At this point, your counterpart will be more open to hearing what you both will lose rather than what he can gain, because no one likes to lose something. This has nothing to do with threats, but with an objective analysis of what you both will miss if you don’t reach an agreement. Use your power to focus your counterparts’ attention on their own interest in avoiding the negative consequences of not agreeing to move forward.

When your counterpart only focuses on the negative aspects of your negotiation, you might be heading toward a lose-lose outcome. Talk about objective and factual consequences and not about what you will do if they don’t agree. It is not about threatening them: it’s about warning them and opening their eyes by projecting them into a future without the benefits of an agreement.

Consider the following situation. You have supplied your services to a foreign company for several years. You have recently been in a very successful partnership with them, working together for one of their clients. One day, that client calls and asks you to supply them with your services. To ensure you are not being unfair to your partner, you ask the client if they want to work directly with you or via your partner. They say that they contacted your partner first, but the partner had proposed another supplier. Since the client had been very happy with your services, they wanted you to give them a proposal for a new project.

While you work on the proposal, your partner calls: upset because you should not be competing with them, since you are their supplier. You explain that they had chosen another supplier this time, and that you have the right to market your services as much as they do—mainly because the client requested this.

Your partner asks you to withdraw your proposal. They almost threaten you, because their company is larger than yours. You try to show them where you both are heading if they continue to behave in this way. You say, “We are competing with other companies. If the client sees that there is animosity between us, they will choose someone else.” You propose a partnership as a solution. You say, “Then everybody wins, and I am sure that the client will select our common proposal.”

Your partner does not accept. They want you to get out of their way. They try another tactic with you: using cultural differences as an excuse. They say you don’t have the same understanding of the terms of your partnership, and that is why you should take yourself out of contention. “We know about our market,” they say. Next, your partner tells the client that they should not consider your proposal. As a result, another company is hired to do the job and, just as you predicted, you and your former partner are out of the game.

Principled Negotiation

Knowing that some people run from conflict and others run toward it, arguing over positions produces unwise outcomes: it is inefficient and endangers an ongoing relationship (Fisher and Ury 2011). Negotiators tend to lock themselves into their positions. The more you defend your position and try to convince the other side, the more your ego becomes identified with your position. Then you end up trying to save your face rather than trying to get an agreement. It becomes a matter of honor instead of business.

There are four points that deal with the basic elements of negotiation and can be used under almost all circumstances (Fisher and Ury 2011):

•People: Separate people from the problem. Avoid being blind because of emotions.

•Interests: Focus on interests, not positions. A negotiating position often obscures the underlying interests.

•Options: Invent multiple options to find mutual gains before deciding what to do. Trying to decide in the presence of an adversary narrows your vision and inhibits creativity.

•Criteria: Insist that the result be based on some objective standard. Use fair factual and objective standards, such as market value, financial results, the law, and equal treatment—anything that can be used as a measuring stick that allows you to decide what would be a fair solution.

Note that standards might have limited impact on more implicit cultures, where perception plays a crucial role in interpreting facts and figures. In contrast, linear negotiators tend to stick to objective standards.

The principled negotiation’s goal is to decide issues on their merits rather than through a haggling process focused on what each side says it will and won’t do. This means that you look for mutual gains whenever possible. However, when your interests conflict, you should insist that the results be based on some fair standards that are independent of the will of either side. The method of principled negotiation is hard on merits, soft on the people. Table 3.8 presents the comparison between soft, hard, and principled negotiation (Fisher and Ury 2011).

Table 3.8 Principled negotiation and positional bargaining

|

Problem |

Solution |

|

|

Soft |

Hard |

Principled |

|

Participants are friends. The goal is agreement. |

Participants are adversaries. The goal is victory. |

Participants are problem-solvers. The goal is a wise outcome, reached efficiently and amicably. |

|

Make concessions to cultivate relationship. Be soft on the people and the problem. Trust others. |

Demand concessions as a condition of the relationship. Be hard on the problem and the people. Distrust others. |

Separate the people from the problem. Be soft on the people and hard on the problem. Proceed independent of trust. |

|

Change your position easily. Make offers. Disclose your bottom line. |

Dig in to your position. Make threats. Be misleading about your bottom line. |

Focus on interests, not positions. Explore interests. Avoid having a bottom line. |

|

Accept one-sided losses to reach agreement. Search for the single answer: the one they will accept. |

Demand one-sided gains as the price of the agreement. Search for the single answer: the one you will accept. |

Invent options for mutual gain. Develop multiple options to choose from; decide later. |

|

Insist on agreement. Try to avoid a contest of wills. Yield to pressure. |

Insist on your position. Try to win a contest of wills. Apply pressure. |

Insist on using objective criteria. Try to reach a result based on standards independent of either side’s will. Reason and be open to reason; yield to principle, not pressure. |

One of the biggest mistakes a negotiator can make is to focus on trying to reconcile the demands of each party when they should focus on reconciling interests. While the demands can be incompatible, the underlying interests can be similar. In other words, negotiators should dig deeper to get to the interests instead of focusing only on the apparent demands. This strategy enables negotiators to have a broader view of the real problem and search for more creative solutions. It is even more important to dig deeper with counterparts from multiactive and reactive cultures, as they tend to dissimulate their real interests by focusing more on relationship than on substance (Malhotra and Bazerman 2008).

Positive thinking gets help from the willingness to understand one another. People say that negotiation is about giving and taking. But when you give first, you are more likely to take more. If you show your genuine willingness to understand your counterpart first, they might reciprocate. This will make your interaction more pleasant and efficient, and you will move ahead faster. Being able to put yourself in your counterpart’s shoes demonstrates that you are flexible, honest, and sincere. Also, once you have shown a willingness to understand their constraints and demands, you may more legitimately present your own difficulties and ask for their understanding.

Taking the first step forward is not showing weakness: it’s showing willingness. You might get some pressure from your supervisor about having to be a tough negotiator. Sometimes you may be criticized for being too nice to your counterparts. Being willing to work together, being understanding, and making concessions is not being weak: it is being wise. As a tough negotiator, you are likely to get what you want faster and without making many concessions, but what you get won’t last very long. It is a short-term strategy.

The long-term strategy is building things together with your counterpart. It is involving them in any decision you may make rather than imposing ways of deciding upon them. When people are associated with a decision, they feel committed and cannot walk away or disagree afterward. There is a personal involvement, because it becomes our decision instead of my decision. It creates bonds among people and high involvement throughout the negotiation process. This is the best way of creating standards to be followed by both parties. Because people hate to contradict themselves, they will be less likely to deviate from what was already agreed.

A good negotiator knows how to be flexible but firm. It means being objective and sincere without being aggressive. You can be tough but friendly. Being understanding and flexible does not mean that you are not firm in your commitments.

There is some confusion between flexibility and changing your mind. Being flexible does not mean that you change your mind every day just to go with the flow. It means that you are able to listen, analyze, and understand other standpoints. It means that you are intelligent. Once you have listened, analyzed, and understood, you can position your offer, make a commitment, and be firm about it. Better yet, you can legitimately ask your counterpart to do the same. Indeed, by making an exception, you create precedents you can use later.

In summary, focus on these four negotiation factors during the encounter: interests for reaching your goals, standards for resolving differences fairly, alternatives to negotiation, and proposals for agreement (Ury 2007).

When Negotiations Go Wrong

Working in situations where everything goes as you have predicted is easy but unrealistic. You should know how to negotiate in situations that can be very different from what you have imagined.

It is often annoying to have a demanding counterpart. Sometimes this feels like a never-ending negotiation, as your counterpart always asks for something more. This is like being nibbled to death by ducks. Instead of being upset by their demands, take these as opportunities to better negotiate. If they ask for more, you may ask for more, too.

This is the way people from several countries negotiate. Latin Americans and some Asians do not ask for everything at once. Just as their negotiating style is incremental, their demands are incremental, too. Once they get your initial agreement about one subject, they will wait to ask more about it bit by bit. You should also take into account their nonlinear perception of time. Because they mix past, present, and future, they see no point in asking for everything they need all at once.

The bargaining phase is over when both parties have agreed on several requests and are happy with the outcomes. Or the negotiation might also be over because no agreement was possible. In this case, the negotiators have few options: abandon the deal, ask for a mediator, and ask for arbitration.

Abandon means that both parties agree to give up on the negotiation, or one of the parties refuses to continue negotiating because it sees no possible deal. Mediation is a third-party negotiation in which one outsider will listen to both parties and help them to reach reconciliation. The mediator’s main role is to take the parties back to objective analysis by showing the advantages for both parties in getting a deal done. Finally, arbitration occurs when one person makes a decision for the negotiators. In this case, the negotiators no longer have the option to decide and must abide by the decision made by the arbitrator.

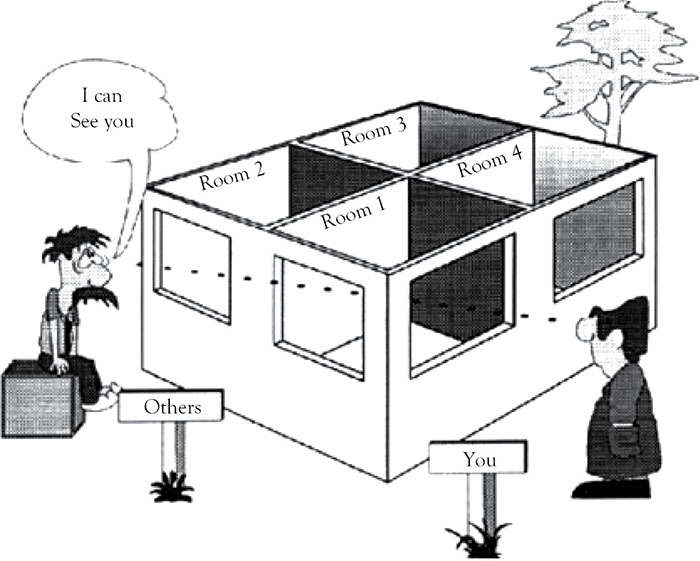

The Jodari house, depicted in Figure 3.8, represents the role of the mediator if the negotiators are unable to see new solutions.

Figure 3.8 The Jodari house

The Jodari House represents the need for creativity and open-mindedness in negotiation. There are only two rooms (Room 1 and Room 4) out of four in the house that you can see. Your counterpart can also see only two rooms (Room 2 and Room 1). You both have one room in common (Room 1) and that is a convenient way of starting your negotiation. As long as your negotiation evolves, you might want to expand the alternatives in trying to attract your counterpart to Room 4 by explaining the advantages of going there. But he cannot see Room 4 and would rather drag you to Room 2, which you cannot see and where you are reluctant to go. Then it becomes a matter of persuasion and the balance of power.

This picture perfectly illustrates the possibilities for negotiators: (1) one common ground to start negotiating, (2) alternatives that each can propose to the other, and (3) one existing alternative that they ignore because they cannot see it. While Room 3 is as much a part of the house as the three other rooms, it does not exist for the two negotiators because they cannot see it. It is a matter of perspective. Only a person placed on the other side of the house could see it is there. Ideally, the third person needs to have a higher view to be able to see the whole house. In addition, the picture represents how much of reality each negotiator can know. Reality and truth are one thing, and the other is how much people know about them. The difference explains the limited number of alternatives that individuals can see.

Ideally, the third person should be someone from your counterpart’s network, with whom you will empathize. Their word has much more impact because there is already trust between them. In multiactive and reactive cultures, this is the only way of doing business. There should always be a third party—with a different but accurate view of the negotiation—whom they trust. Everything works via recommendation. You will need someone to open the doors for you and to help with supporting your arguments.