Merging Culture With Negotiation

There is a lot of research about the influence of culture on business negotiations. However, while everybody knows that culture and cultural differences exist, not many have experienced it to know what they are really talking about. “Culture is like gravity: you do not experience it until you jump six feet into the air” (Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner 2006, 5). This chapter explores the main cultural dimensions, as defined by the most relevant researchers who specialize in cultural understanding. You will see how pervasive culture is in people’s lives and its undeniable impact on negotiation.

What Is Culture?

There are more than 250 scientifically validated definitions of culture. The irony is that this can be explained by the lack of certainty about what culture really is. When analyzing human behavior, researchers were unable to use well-known concepts to explain some of it. That led them to say these factors are due to cultural specificities. No one really knows exactly what culture includes and, as stated by Tylor (1913), “culture is a complex whole that includes arts, morals, laws and any other capabilities acquired by men to be a member of a society.”

While there are many definitions of culture, they all share two common aspects: culture is a group-level phenomenon, and it is learned. Values, beliefs, and expectations about behavior are passed from one generation to the next. This creates general guidelines for the acceptable manners of conduct within a society.

Culture has an impact on social or professional behavior because it shapes people’s mentality and dictates norms that all members of the society follow. Culture is rooted in deep values: both conscious and unconscious. Ask yourself if you would be able to explain to some foreigner why you do things the way you do in your country. You are more likely to answer, “because this is the way we have been doing it forever” than to explain the real reasons. Since culture is specific to one society, this implies cultural differences among different societies. That leads us to the cultural differences we face in our day-to-day international business relationships.

The Impact of Culture on Negotiation

Culture has three obvious impacts on negotiations. First, there is the mindset. Depending on how people were alphabetized, they will be more verbal or more visual. Second, there are the norms that dictate behaviors. For example, the way we should address people, taboo topics we are not allowed to bring up, the food we eat and the way we eat it, and so on.

Third, negotiations require a great deal of social activity. These integrate rituals and traditions important to locals. As an international negotiator, you are supposed to know about them and be open to participate in some of them. As an example, when negotiating in some Middle Eastern countries, you might be surprised to be invited to weddings and other family parties, especially if you don’t have a close personal relationship with your counterparts. The objectives are twofold: first, they need to take you out of the office to get to know you better as an individual. They would also want to see how flexible and open-minded you are. Second, they organize huge parties for such celebrations. The more people who attend them, the better. It’s a sign of power.

International etiquette has long been used as a key factor in books and training sessions about international relationships. You are informed about how to greet people in different countries, which topics to avoid, gift-giving practices, and business card exchanges. Although this is relevant and useful, it is not enough when you’re preparing for a negotiation.

Observing cultural social norms is paramount to understanding human behavior. But a negotiator should know about the impact of culture on negotiation strategies and styles. Culture influences negotiation on several levels: individual or team negotiation, the amount of time needed to reach an agreement, the value of concessions, the amount of social life integrated in the negotiation process, the influence of family, and risk taking, just to name a few.

Although a little understanding is better than nothing, it might not be enough to enable people to negotiate internationally. Studying and understanding other cultures is a different job. Negotiators might make a lot of effort to get to know other cultures, but they can never specialize in it. The best alternative is to be accompanied by someone who can specialize. Negotiators then may focus on their strategies and leave the cultural understanding to an expert who can open the doors for them.

Research suggests that people negotiate differently when they are with people from their own culture versus those from other cultures. Because cultures develop to facilitate social integration, it follows that social integration will be lower when there are multiple cultures in a group (Stahl et al. 2009).

Overcoming the “My Culture Is Best” Bias

Triandis (2006) adds the inescapable reality that all humans are ethnocentric. That is, they strongly believe that what is normal in their culture should be normal everywhere. Anything different is abnormal and wrong. To overcome this bias requires a great deal of effort because, to some extent, it goes against human nature. If you only know one cultural system, it is inevitable that you will be ethnocentric. Overcoming this requires an ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. But this can entail a tendency to question one’s own cultural norms, which can make people feel uncomfortable. That is why international negotiators must have considerable adaptability.

Now that we are talking about tolerance, acceptance, and nondiscrimination, it seems like everybody is open-minded and ready to adjust. We might think that it is natural to accept cultural differences—but it’s not. People are self-centered and don’t want to make a lot of effort to understand differences or to adjust. Negotiators leave it to the balance of power: the one who needs the other party more badly has to adjust. Some cultures are easier to adjust to than others. It depends on the cultural distance.

Understanding Cultural Distance

Cultural distance is the gap between your culture and other cultures. The bigger the gap, the bigger the distance and, thus, the bigger the effort needed to adjust. It also requires more effort to find common ground between the parties, since they don’t share similar values and behaviors.

Consider the following situation. You accompany a French client on a one-week negotiation in Chicago. You think that it will be easy, because France and the United States are developed Western countries and so the cultural distance might not be significant. Throughout the week, however, you realize that you are having some trouble getting your French client to work productively with the Americans. They don’t manage time the same way. They use agendas differently, and their mindsets are definitely different.

However, everything goes well until the closing gala dinner. The day before, your French client is invited to sit at the table of honor. He is flattered and looks forward to the event. The next evening, by the end of the predinner drinks, he tells you that he expects someone to accompany him to the table. You explain him that he is expected to go to the table at the scheduled time, as he has accepted the invitation. After a while, when everyone already is seated, he joins you at your table. He complains that Americans don’t know how to look after their guests. On the other hand, the Americans at the table confirm their stereotypes about the French being unreliable, because they do something different from what they say.

Cultural “Animals”

One way of finding similarities among cultures is by comparing them to animals, which was done by Lewis (2012). Some cultures are like cats, some are like dogs, and others are like horses.

Cats tend to dominate others. They are independent, loosely loyal, and know how to charm others when they need them.

Dogs are happy to be dominated as long as they get something in return, which can be physical (such as food) or psychological (like love). They are extremely loyal and reliable.

Finally, horses are bigger than humans but agree to be dominated. They are hard workers, but there are some rules that should not be broken (mounting from the left side, for example) or the consequences can be dangerous. A horse obeys coded signals sent by the horseman with the reigns, but can bite him or throw him off if it is not happy with the treatment it receives.

Maybe you realize that your culture (or just you) is more like a dog, a cat, or a horse. And you know that cats and dogs don’t get along well, but it is not impossible to bring them together. Dogs have little respect for cats. Cats think that dogs are weak, without any personality. Horses can tolerate both dogs and cats, but know they will never do anything together, because of their considerable difference in size and speed.

It is easier to represent human personalities by using metaphors such as animals. Cartoons are a good example. People feel freer to laugh at or to criticize them, which is not nearly as acceptable to do with other human beings.

Another useful aspect of analyzing animals when trying to understand intercultural relationships is to see that they don’t mix species. They live in tribes and defend their survival and territory. Most importantly, they preserve their race. By extension, tolerance and acceptance of other cultures is not natural to humans either. We must learn to be open to other races, cultures, and rituals. That is why it requires a great deal of effort and willingness to work with other cultures.

Culture Through the Eyes of a Child

It you want to know what behavior is natural for human beings, observe children. They are spontaneous before they socialize. They like novelty but not differences. They reject other children who are not like them, and often with some cruelty. After being socialized, they learn not to behave this way and that they must accept differences. As adults, this is what negotiators do when working with other cultures: accepting that differences exist and trying to cope with them in order to work together.

We also receive an inconsistent education throughout our lives. As children, we reject and accept only what is useful to us. We claim what we need anytime we need it. We follow no social rules. As soon as we start socializing in kindergarten (or even at home), we learn to separate and classify objects by colors and shapes. When a child wants to put a triangle in a place designed for a square, he is corrected because his choice is wrong. Special toys are created to prevent children from inserting anything that isn’t the right shape.

The same thing is true with colors. When children mix objects with different colors, they are corrected and told to group the blues with the blues, the greens with the greens, and so forth. Then, when we are adults, we are told to accept people with different colors, shapes, and mentalities.

The Importance of Respect

Cultural differences in negotiators’ behaviors imply that the environment for the negotiation might not be naturally favorable. Not respecting cultural etiquette might not doom your negotiations, but it will make it harder to get what you need from other people. Your counterparts will have more respect for you if they see that you have studied their culture and have some knowledge about it. In addition, you will feel better prepared and less vulnerable if you know more about the other side’s culture.

Intercultural interactions in negotiation are not about adjustment, they are about respect. You are not expected to become one of them. You are expected to behave consistently with your culture as well as to be culturally aware to respect local norms. As such, you are not expected to wear the local clothes, but to respect the local dress code by wearing your own clothes. Your counterparts already have a certain perception or knowledge of your culture. Stereotyped or not, it is the way they see your culture and expect you to behave accordingly.

People know more about some cultures than others. They expect certain behaviors from you. For instance, the American culture is broadcast worldwide thanks to movies and TV shows. Although these might not represent all Americans, they give an idea of the country’s way of life to other cultures. In contrast, some other countries—such as Armenia or Paraguay—are obscure to more than half of the world’s population, because information about them rarely is shared. That is why negotiators must also have some country-specific information.

The Myth of a “Global Culture”

The dilution of cultural differences into a more global culture is more a myth than reality. Cultural specificities are getting even stronger in some emerging cultures, which wish to maintain their independence from historically dominating cultures. This means negotiators need to think like cultural translators. They should be able to decode both words and behaviors, as some cultures might use proverbs and metaphors to say “no” or to convey any disagreement.

When working with African counterparts, you might hear such quotes as, “To run is not necessarily to arrive.” “However long the night, the dawn will break.” The first proverb will tell you not to rush people. In African cultures, people take their time to live, to get to know other people, and to build relationships. You will get nowhere with them if you try to rush. You will be perceived as a cold, distant person, unable to enjoy interacting with others.

The second proverb shows you their fatalistic mentality. What is to happen will happen sooner or later. The way may be tough, but it will eventually happen, and there is not much you can do about it. You cannot take hasty initiatives or try to control the situation and the events, because this is not the way they understand and handle life.

“Saving Face” and Disagreements

Finally, negotiators need to know how to disagree or to explain themselves without making others look bad. You have heard about the importance of saving face in China, and this concept is true elsewhere. People in several other countries are concerned about preserving their and others’ faces and want to avoid unpleasant and conflicting situations.

It is easier to understand this when you know that losing face is about dignity, sense of honor, and consistency. It is not just about disagreeing with someone else in front of others. If you are not aware of the cultural norms, there is a high probability that you will be rude without even knowing it.

Once a Brazilian purchaser was waiting for a reply from a Japanese supplier about a certain product. After several weeks with no news from the supplier, despite her reminders, the Brazilian purchaser started pursuing him by phone and e-mail. When he did not reply, she lost her temper and sent a very assertive message. She asked him directly if he really wanted to work with her company—with several question marks at the end of her sentence. If so, she suggested that he do his job properly. Even worse, she copied his and her own supervisor on the e-mail.

She did not realize how much damage her action would cause to the Japanese counterpart. If she had been culturally aware, she would have asked him about peripheral topics, which would then lead him to answer her main question. She would know that he would never give her a negative answer or make her aware of any problems he was having with her request.

The Role of Communication

You understand that communication plays a crucial role in negotiation. Worldwide, nonverbal communication accounts for about 65 percent of how people get information. In many cultures, behavior counts for more than half of the message being conveyed. You must know about implicit communication to understand what your counterparts are telling you, without saying it with words. If you are unable to observe and decode their behavior, you will miss very important information.

Do not expect people to say everything clearly. Some cultures have a greater behavioral component in their communication, while others are just implicit and say different things with the same words. There is also what is called second degree communication. In this case, the interpretation depends on the pronunciation and the emphasis on specific words. You are supposed to read between the lines. Typically, these are cultures where people don’t take you at your word and always look for something behind them, “What did he mean by that?”

Consider the following situation. You are working with a Brazilian counterpart on a project, and you are ready to sign the deal. The few times you have interacted with him, he said that everything was OK on his side. When you finally meet to sign the agreement, the Brazilian avoids talking about your business topic, keeps smiling and making jokes, and creating brief diversions.

After playing his game for a while, you get to the point and ask him about the agreement. You realize his company has done nothing. But he would never have told you because that would involve losing face, and he was probably waiting for the solution to appear by itself or from someone else. Ideally, he would be expecting that you had not done your job, either. You certainly surprised him by having everything completed on time.

The All-Inclusive Verbal and Nonverbal Communication

If you get confused and ask your counterparts to be more explicit about what they mean, that won’t improve matters. From their perspective, they already are being clear. Moreover, they are not always conscious of which portion of their communication is implicit versus explicit. To them, it is just communication. Actually, what you say is less relevant than what they hear. Make sure that there is consistency between both sides. What sounds confusing to you may sound loud and clear to others.

Putting Cultures in Context

Hall (1976) identified two extremes of a cultural dimension, depending on the cultural context. After having analyzed 11 cultures, he placed them in a continuum, stretching from high-context to low-context cultures.

He defined low-context cultures as the ones in which the communication is more objective: with a small portion of nonverbal messages and less dependent on relationship building. In these cultures, social and professional lives are clearly separated. On the other end of the continuum, he placed high-context cultures, which are more implicit. They add a considerable amount of nonverbal communication and include personal relationship and the practice of rituals as part of their professional relationships.

In other words, low-context cultural environments expect and reinforce making meaning explicit. They block out the potential interference of nonverbal or other contextual sources. In high-context cultures, the successful exchange of information hinges on the ability to apply a shared and implicit framework of interpretation to a message. Some of the cultures he analyzed, ranked from higher to lower context, are represented in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 From high- to low-cultural contexts

In some cases, Hall analyzed one country. In others, he grouped countries into regions. Make sure that when you work with a specific country in one of those regions, you understand the cultural differences among them. For example, if you work with a Latin American country, you need to know that they all belong to a high-context culture, but they have their own specific culture.

Another important aspect to take into account when using Hall’s model is to understand the relative value of it. For example, negotiators from the United Kingdom are perceived as implicit and difficult to assess by the Germans, but too direct and assertive by the Arabs. Countries such as France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Spain (which are in the center the model) are more complex to understand, and people’s behaviors are hard to predict. They can be seen as being very objective or very subjective, depending upon who is doing the comparison.

Once a French purchaser was working with a Swiss counterpart. When he had a technical problem with a machine produced in Switzerland, he called his counterpart to ask him for some help, because they have a good relationship. After greeting his Swiss counterpart the French negotiator asked him if he knows how to fix the machine. The Swiss answered, “No.” The Frenchman was upset. He expected that his counterpart would automatically help him to find someone else to fix the machine. He did not realize that the low-context Swiss had just answered to the question he had asked. If he wanted further information, the Frenchman would need to ask more questions.

It is worth noting that of the 38 cultures analyzed by Hall, only 12 are low context. That means you are more likely to work with high-context cultures in international negotiations.

Cultural Relativity

Everything about culture is relative. The concepts and the models created by researchers are often represented by continuums in which we can locate countries by comparing them with others. In doing so, we tend to say that Country A is more objective than Country B, which is more particularistic than Country C, which in turn is more individualistic than Country D.

Think about the trips you have taken. You will remember every place that attracted your attention by the strangeness or uniqueness of local people doing something differently from your habits. It is through comparison that you get to better know your culture of origin and the new one you are in.

Everything seems normal in the country where you were born and raised, because people tend to follow the same norms, which is why you take your culture for granted. The first time you go abroad, you are surprised to notice different ways of doing the same things. Intrigued by that, you compare and try to understand where the differences come from and which alternative best fits you.

This comparative approach is called cultural relativity. Everything is relative, and absolute measures do not make any sense in international settings. The most salient expression of cultural relativity is time management. You may spend the same amount of time on two different activities. One of them will seem to be time well invested, and the other one a waste.

Your counterpart from other culture may have exactly the opposite perception. For example, negotiators from low-context cultures perceive small talk and conversations about private lives a waste of time. On the other hand, negotiators from high-context cultures gladly invest time in their negotiation by getting to better know the person they are likely to work with.

Would You Rather Have Peaches or Coconuts?

Another very important aspect in building a relationship with counterparts is to know about how and what people like to communicate with each other. Some people are like peaches: soft, agreeable to touch, sweet, and easy to get along with. These people talk to strangers, are easy going, readily speak about their private lives, and make other feel comfortable—as though they were already friends. But when you want to go deeper into what looks like friendship, you bump into the pit. They do not wish to reach a deeper level of intimacy with you. Anglos, Latin Americans, and Africans are some examples of peaches.

Then there are the coconuts. They are hard to get into. You need adequate tools to break the hard shell. But once you are in, it is sweet and agreeable and there are no more obstacles. Negotiators from Europe, the Middle East, and Asia are examples of coconut cultures. The metaphor was coined by the German-American psychologist Kurt Lewin in the 1920s, when he was working with Americans (peaches) and Germans (coconuts) and studied the reasons why they find it difficult to understand each other and work together.

Language Barriers and Translators

Cultural differences can greatly interfere with the communication process. Effective communication requires people to have at least a minimum of shared language around which to align. Different country-based cultures often have different languages. Even when they share a common language, they may not always translate meaning in the same way. The different values and norms among people from different cultures make it difficult for them to find a shared platform or a common approach (Stahl et al. 2009).

If you think that everybody can speak English, you are just partially right. More companies from non-English-speaking countries are adopting English as their working language. It does not mean, however, that all their negotiators feel comfortable when negotiating in English. And even when the negotiations take place in English, there are always those moments when the other team will speak in their native language, which you cannot understand, and you will wonder what is going on. In addition to getting familiar with many different accents in English, you should also be ready to feel (or look) comfortable when the other party interacts frequently in its mother tongue, even though you do not understand it.

Without trying to speak all needed languages, you should at least know some basic words in order to show interest and respect. It will be greatly appreciated if you can greet and thank people in their own language. However, you should avoid using terms and expressions that are restricted to the locals, because you do not follow their implicit meaning. One example would be those that relate to religion.

Just as no negotiator can speak all needed languages, no one can know about all cultures. These are different jobs. Being a negotiator is not being a translator, nor is it being an interculturalist. Negotiators have the choice between (1) negotiating in English and being aware of the limited understanding they will have with non-native English speakers, or (2) asking for an interpreter, whose job is to translate.

Likewise, negotiators can attempt to know about cultures themselves. They may try to negotiate well in all cultural contexts while having limited understanding of them, or they can be accompanied by a person whose job is to deeply understand all cultures. Even if you can speak other languages, you have a hard time trying to translate sentences into your own language. This happens because translation and interpretation have specific techniques that it takes people several years to learn.

The same happens with interculturalists. You may know about some cultures and be able to use some tools to keep moving ahead with your international negotiations, which is the goal of this book. But you will never be able to perform as well as when you are accompanied by a person who masters all the tools and has been prepared to interact with other cultures for years.

All cultures don’t have the same relationship with their language. This means that some are pickier about the excellence in mastering their language. They want to avoid having you massacre it by turning to English as soon as you start speaking their language. Others will feel flattered and will be happy to help you with pronunciation and vocabulary.

For example, the French are very picky about their language. They can hardly bear someone who can’t speak French properly, and they would rather switch to English or any other language they can speak instead of listening to someone who speaks French poorly. Consistently, French negotiators are known for having few language skills and for feeling uncomfortable when negotiating in English. This is because the French in general don’t allow themselves to speak a language that they can’t master at the same level as their mother tongue—so they don’t practice it.

A common way of overcoming language barriers in negotiation is using translators. They have the big advantage of saving you the effort of speaking other languages and preventing misunderstandings due to word choices. Translators also can help people to save face. In a recent visit to Japan, the president of France called his audience Chinese. The French-speaking attendees were shocked, but the translators saved him by replacing his word with Japanese.

But using interpreters might sound easier than it really is. First, you will need to find an interpreter with some technical knowledge, to talk about your offer with the same accuracy that you would. Second, you cannot be sure about what and how your message is being interpreted. Because you cannot understand what the translator is telling your counterpart, you can only hope that the other party is getting the message you really want to convey. Because of that, negotiators often take their own interpreters to the negotiating table just as they do with their own lawyers. Then one interpreter can supervise the other one to make sure that there is no misinterpretation.

This is a real concern for negotiators, because having other people stand between you and your counterpart will slow down negotiation. You will not be in charge of timing and able to give the needed emphasis to what you want to say. Interpretation of nonverbal communication might be disturbed as well. You may be surprised to see that what was supposed to be your negotiation ends up being the interpreters’ negotiation, because they spend so much time supervising and correcting each other.

Finally, intercultural communication is about encoding and decoding. All languages are codes we use to communicate with each other. These can be gestures, words, and facial expressions. Communicating with people from other cultures is not much different than communicating with cats, dogs, or horses. As they don’t understand your words, you need other cues to help them understand what you say. Pavlov demonstrated that phenomenon by classical conditioning, when he taught his dog to understand a ringing bell meant that its food was served.

The Pitfalls of Distant Communication: Videoconferences, Conference Calls, E-mails, and Other Technology-Based Communication

Financial turmoil has caused companies to search for ways to reduce costs, including cutting travel expenses. As a result, negotiators are turning into distant negotiators. They discuss price, delivery, and other relevant topics via conference calls and videoconferences. Using technology-based communication is a clear advantage in business, as it offers the benefits of speed and being in touch with counterparts as often as needed at very low cost. The disadvantage is that a considerable amount of nonverbal communication is hidden, and building a relationship is almost impossible. There is nothing that you can experience together with your counterpart by using Skype, MSN, or any other real-time communication technique.

But e-mails don’t prevent negotiators from socializing. You can always add some off topic or personal interactions with your counterpart. You also can be friendly and enthusiastic. However, it is much harder to interpret emotional undertones in e-mail communications. Finally, it prevents the projection and identification phenomena between people facing each other, which is so important to create empathy.

Using e-mail is undoubtedly very comfortable. But remember the message you write today is colored by the feelings you have today. The person who receives your message will not read it in the same mood you were in when you wrote it, and should be able to understand the message you are trying to convey. Sometimes when you are in a time crunch, you just reply to an e-mail very quickly. Understand that this can be taken as rudeness on the other side.

The use of smartphones is also very convenient, as it makes negotiators accessible all the time. The tricky aspect is that you might be tempted to reply immediately—without giving much thought to the subject—and use inappropriate language. In addition, the short length and abbreviations used in texting—sometimes exacerbated by the phone’s autocorrect function—greatly increases the likelihood of unintended misunderstandings.

Moreover, the use of smartphones is not practiced or accepted in the same way everywhere. In some cultures, people will check their messages and take calls during a meeting, while in others this is perceived as very disrespectful. Research demonstrated that people using their smartphones during a negotiation are perceived as cheating, because they are getting more information than the other side. You can use this situation to create a concession in a negotiation that is underway. By using his phone while you did not use yours, you may say that your counterpart has unbalanced the negotiation terms, so he (implicitly) owes you a concession to get the negotiation back in balance.

Conference calls are used every day by international negotiators. These can be very confusing when there are several people talking at the same time—on one or both sides. Indeed, if there are a number of people on the call, you might be confused during the discussion and not know exactly who is saying what. This phenomenon is compounded if you work with polychronic cultures, in which people handle several tasks at the same time.

Polychronic Versus Monochronic Approaches to Tasks

Polychronic individuals go back and forth on the same activity, pausing when they are interrupted by other tasks or other people. They don’t mind stopping something in favor of something else, and then coming back to what they were doing before. Also, they feel comfortable when someone cuts them off during conversations and do not get lost when many people talk simultaneously.

If you are a monochronic person—who handles one task at a time—you might feel a bit lost in this environment. These people schedule and allocate specific time slots for each activity. They lose their place when they are interrupted and get very disturbed when several people talk at once. Moreover, in monochronic cultures, meetings start and finish on time. The agenda is followed from top to bottom, and once a topic was already discussed, it is not revisited.

Here is another aspect to take into account. If you insist on reaching an agreement separately for each issue in your agenda, it might not only not suit your polychronic counterparts, but also prevent you both from having a more holistic view of the whole deal and finding better possibilities for trade-offs.

On the other hand, the polychronic negotiators feel comfortable in situations where several activities are happening at the same time. They view time as more flexible and spend a good amount of it just talking with people about superficial and informal topics. The agenda is not sacrosanct, and even when the meeting is over, they might remain to interact with others. Being late or postponing appointments is usual in polychronic cultures.

These differences in time management are meaningful. Assign a monochronic and a polychronic person with the same three tasks. After a while, the polychronic will be able to tell you a bit of each one and how she is handling them, but she will probably be late to hand them in and might negotiate the deadline.

At the same time, the monochronic will be just able to tell you about the first task, because he would not have started any others before he is done with that one. He will be able to go deeper into the description of what he has been doing for the first task, but unable to tell you about the remaining ones. This might be misleading, as you might think that the monochronic has not understood that there were three tasks to be done. However, he will respect the deadline and finish the three projects on time.

Main Cultural Orientations

Hofstede and Hofstede (2005) state that the world is full of confrontations between people, groups, and nations who think, feel, and act differently. At the same time, these people are exposed to common problems that demand cooperation for their solution.

Culture is defined as a mental programming, because all people carry within themselves patterns of thinking, feeling, and potential acting that were learned throughout their lifetimes. Much of this information was acquired in early childhood, because that is when a person is most susceptible to learning and assimilating. As soon as certain patterns have established themselves within people’s minds, they must unlearn these before being able to learn something different—and unlearning is more difficult than learning for the first time (Hofstede and Hofstede 2005).

The authors also point out that culture should be distinguished from human nature and personality. Human nature is what all people have in common. Culture is always a collective phenomenon, because it is at least partly shared with those who live or lived within the same social environment. Culture is learned, not innate. It comes from one’s social environment, not from one’s genes. Personality is one’s unique set of mental programs that need not be shared with any other human being. It is based on traits that are partly inherited from the individual’s unique set of genes, and partly learned, as shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Hofstede’s pyramid of human uniqueness

In analyzing cultural differences, Geert Hofstede identified four major dimensions of culture and mapped their distribution among managers from more than 70 countries, as seen in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

According to Hofstede and Hofstede (2005), national cultures will affect negotiations in several ways:

•Power distance will affect the degree that control and decision making are centralized, and the importance of the negotiators’ status.

•Collectivism will affect the need for stable relationships between negotiators. In a collectivist culture, replacing a person means that a new relationship must be built, which takes time. Mediators have an important role in maintaining a viable pattern of relationships that allows progress.

•Masculinity will affect the need for ego-boosting behavior and the sympathy for the strong on the part of negotiators and their superiors, as well as the tendency to resolve conflicts by a show of force. Feminine cultures are more likely to resolve conflicts by compromise and to strive for consensus.

•Uncertainty avoidance will affect the (in)tolerance of ambiguity and (dis)trust in opponents who show unfamiliar behaviors, as well as the need for structure and ritual in the negotiation procedures.

•Time orientation is the fifth dimension the authors identified. It relates to short- and long-term results and relationships.

To understand the impact of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions on negotiation, consider the graph in Figure 2.3.

The American negotiator belongs to a flatter and more individualistic culture, so is more autonomous in decision making and will probably negotiate alone. His Chinese counterpart will be part of a team of negotiators and will need hierarchical approval of any decisions. Although there is not much difference in terms of masculinity, the Chinese might be more concerned about the negotiation failing than the American, who, by the way, will be also less inclined to take risks than the Chinese—who have a lower score for the uncertainty avoidance dimension.

There is a huge gap between both cultures in time orientation. The American negotiator will focus on short-term results and would rather go faster with the negotiation process without spending (wasting) much time in building relationships. However, his Chinese counterparts will spend as much time as needed before getting to a deal. They focus on long-term relationships. They need to invest time in getting to know the people they will be working with. Finally, the American negotiator will focus more on signing a contract as a way of closing the deal. His Chinese counterparts will look for a long-term relationship through collaborative work once the contract is signed.

Everybody seems to be puzzled by the rapid deployment of Chinese investments around the world. Analyzing the scores presented previously can easily explain this. As people belonging to a strong hierarchical culture (power distance), the Chinese obey and honor the elderly. This means both parents and government are investing in the younger generations, so this group may make their contribution to take China to the top of the most powerful economies in the world. To do so, the Chinese go abroad to study, to work, and to run companies. Nothing—from new languages to new disciplines—seems to be a barrier to their determination to achieve their goals (masculinity).

The country’s low score in uncertainty avoidance explains how much of a risk the Chinese are willing to take. However, they take risks collectively, which is reassuring to them. They are always in groups with other Chinese, and they stick together wherever they are (collectivism). This allows them to speak Chinese and eat familiar food, benefitting from Chinatowns spread throughout the main cities in the world. Their long-term relationships explain why they only work with people from their families or with other Chinese. It is a matter of trust (long-term orientation).

Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (2006) explain cultural differences as each culture choosing specific solutions to certain problems that reveal themselves as dilemmas. Thus working in international settings is about reconciling the dilemmas, as shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 Reconciling dilemmas in Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s cultural dimensions

|

Affectivity Feeling, emotion, and gratification |

Affective neutrality Practical or moral considerations |

|

Self-orientation Self-interest |

Communitarianism Group goals and interests |

|

Universalism Using common standards to evaluate situations and groups |

Particularism Using different standards to evaluate situations and groups |

|

Ascription Stressing who you are |

Achievement Stressing what you do or have done |

|

Specificity Interaction for specific purposes |

Diffuseness Interaction across a wide range of activities |

Affective negotiators are warm and welcoming. They show their feelings (genuine or not) when they are happy or unhappy with how things are going with the negotiation. Neutral negotiators feel uncomfortable with these expressions, as it looks fake and un-businesslike to them. They would say, “Why should we be delighted? We’re just doing our job here.” Russians, for example, find it hard to trust someone who uses gestures, moves around, and shows facial expressions when speaking. They think that their interlocutor is creating a diversion from the substance of a negotiation and might be untrustworthy.

Those who are self-oriented will take responsibility for the negotiation. This person will feel more concerned about the outcomes of the negotiation—and the job she is doing—rather than how the rest of the group performs. In universalistic cultures, negotiators have a binary view of life: things are divided between what we are allowed to do and what we are not allowed to do. All people are submitted to the same rules.

By contrast, in particularistic cultures, norms are obscure and depend on the person. What is not possible to someone is possible to someone else. There is a lot of favoritism in particularistic cultures. Your negotiations will go nowhere if you are not friends with the right people. More companies are trying to avoid the bribes developed by these cultures, in which being friends also means doing favors. Gift-giving practices are being coordinated, and negotiators are just allowed to offer their company’s goodies to stop with the flow of luxury products being used as persuasion tactics in negotiations.

If you belong to an achievement-oriented culture, you might be more interested in your counterparts’ achievements as a businessperson and a negotiator than in his personal background. But if your counterpart is from an ascription culture, she is more likely to investigate your private life to identify your family name and the networks you belong to. She might also be more interested in your diplomas than in your working experience.

Finally, negotiators belonging to a diffuse culture mix private and professional lives. In Japan, for example, the boss is also a father, and should protect his employees. As a result, the employees are at the boss’s and the company’s disposal at any day and time. There is no way that they will leave the office at 5:00 p.m. as people do in other countries.

If you are a negotiator from a specific culture, you will work from 9 to 5 and then leave time for your private activities. What happens when you become an international negotiator and go to Japan, a diffuse culture? Your counterparts will pick you up at any time (day or night) and at any day of the week you arrive. They will take you to your hotel, make sure that everything is arranged, and then take you to visit and dine with them. They will look after you and take you everywhere throughout your sojourn in Japan because, in a diffuse culture, accompanying you at all times is part of doing business with you.

Businesspeople from diffuse cultures are always disappointed when they negotiate in specific cultures, because they don’t receive the same treatment. More often than not, they have a map, directions to the meeting place, and the time for the meeting. They are taken to a dinner and a lunch, and the rest of the time they are on their own.

Values and Communication

Lewis (2012) states that human beings organize their lives around two core features: values and communication. These elements usually remain constant in a person’s behavioral make-up. This is principally true because people—when faced with the trials and vicissitudes of life—have a strong urge to seek security in traditional behavioral refugees.

Lewis’ LMR model divides cultures into three categories:

•Linear-active people tend to be task-oriented, highly organized planners who complete action chains by doing one thing at a time, preferably in accordance with a linear agenda. Speech is for information and depends largely on facts and figures.

•Multiactive people are loquacious, emotional, and impulsive. They attach great importance to family, meetings, relationships, compassion, and human warmth. They like to do many things at the same time and are poor followers of agendas. Speech is for opinions.

•Reactive people are good listeners and rarely initiate action or discussion. They prefer first to hear and establish the other’s position, and then react to it and formulate their own opinion. Reactives listen before they leap. Speech is for creating harmony.

Now you know why negotiation is above all a human interaction, and this is the reason why culture has such an impact on it. If negotiators from different cultures behave differently, it is because their cultures are anchored on different values. Lewis described anchors for the three types of cultural categories, as demonstrated in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3 Cultural anchors according to Lewis

|

Culture |

Characteristics |

Anchors |

|

Multiactive |

Talkative, warm, relationship-oriented |

Family, hierarchy, relationships, emotions, eloquence, persuasion, loyalty |

|

Linear-active |

Scheduled, factual, task-oriented |

Facts, planning, products, timelines, word-deed correlation, institutions, law |

|

Reactive |

Listening, accommodating |

Intuition, courtesy, network, common obligations, collective harmony, face |

The anchors described in this table represent what is valued in each type of culture—and by its negotiators. If you are a negotiator from a linear culture, you need tangible elements—such as products, facts and figures, and contracts—to get to a deal. However, a multiactive negotiator will search for personal commonalities, persuasion based on emotions, and tell about things instead of proving them with concrete measures. Finally, the reactive negotiator never disagrees, does not demonstrate emotions, and uses the network as a guarantee for a deal.

Cultural anchorage influences decision-making preferences across cultures, as represented in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4 Cultural preferences according to Lewis

|

Type of culture |

Preferences |

|

Linear-active |

Compromise Take a vote (majority rule) Debate vigorously and come to some conclusion Use common sense Let’s decide today Let implementation follow quickly Avoid ambiguity Dislike chopping and changing Decisions are final |

|

Multiactive |

No piecemeal decisions Let’s discuss everything comprehensively Lateral relations must be considered Majority rule has a fundamental weakness: the minority might be right Matters need not all be decided today Bosses make decisions: have we consulted them? There is no such thing as international common sense A good decision is better than a consensus or compromise Relationships are more important than a hard-and-fast decision |

|

Reactive |

There is nothing new under the sun Decisions, therefore, should be based on best past precedents Decisions are best if they are unanimous One should not submit to the tyranny of the majority, but reason with all until unanimity is achieved A harmonious decision is better than an acrimonious one, however convincing |

It is paramount to know about cultural values in negotiation, because you need to create value before you claim it when you are bargaining. Getting to a deal implies that all counterparts are happy with the outcomes of the negotiation, and the condition for it to happen is that all parties get what they value.

Schwartz and Bisky (1987) studied the motivational goals underlying cultural values and identified 10 fundamental values. Schwartz’s works represent the most comprehensive exploration of cultural values to date. His typology, presented as follows, has been found to be universal and stable across gender, age, socioeconomic groups, cultures, and generations.

•Achievement (personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards)

•Hedonism (pleasure and sensuous gratification)

•Stimulation (excitement, novelty, and challenge in life)

•Self-direction (independent thought and action; choosing, creating, and exploring)

•Universalism (understanding, appreciation, tolerance, caring about humanity and nature)

•Benevolence (preserving and enhancing the welfare of loved ones, friends, and family)

•Conformity (restraint of actions and inclinations)

•Tradition (respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide the self)

•Security (safety and harmony, and the stability of society, relationships and self)

•Power (social status and prestige, control or dominance over people and resources)

Schwartz also empirically demonstrated that if you place these values in a mathematical two-dimensional space, they will form the so-called circumplex structure: the values with similar motivational goals will end up closer to each other, and the values with conflicting motivational goals will be further apart, as shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4 Schwartz’s fundamental values

When analyzing this graph, you can imagine how a negotiation between people from opposite sides would look. Those on the conservation side would be more reluctant to take risks and less open to innovation. They would stick to what they know and would not be defined by creativity. This means the open-to-change negotiator needs to be reassuring and slowly introduce new ideas or alternatives to the deal. In addition, the self-enhancement negotiators would want to achieve the best deal for themselves, because they like power and need to show what they are able to accomplish. However, they will have a hard time trying to persuade the self-transcendent negotiator, who is more altruistic and looks for universal benefits.

To understand the roots of cultural differences in avoiding or competing in conflicts, you need to understand cultural values. Self-enhancement and achievement. Conformity and tradition. The traditions view to negotiations—associated with the Western world—would be to deal rationally, focus on economic capital, have dispositional attribution, and use direct information and direct voice. In contrast, the alternative view to negotiations—applicable to many non-Western countries and regions—would use emotionality in making concessions, focus on building relationships and social capital, demonstrate situational attribution, and use indirect information sharing and indirectness in communication (Khakhar and Rammal 2013).

More recently, Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) was conceived by Robert J. House (House et al. 2004) of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in 1991. It involved 170 country co-investigators, based in 62 of the world’s cultures, as well as a 14-member group of coordinators and research associates. To aid in the interpretation of findings, the researchers grouped the 62 societies into 10 societal clusters or simply clusters, as shown in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 The GLOBE 10 societal clusters

In the GLOBE model, it is useful to know which clusters you and your counterparts are in. Then you should refer to the other researchers’ dimensions to know what characterizes the cultures you will be working with. If you are in the Anglo cluster, you know that it will be easier for you to find commonalities with other countries from the same cluster. You share several cultural traits, such as being linear-active, and having low scores in power distance and in uncertainty avoidance, and high scores in individualism and masculinity. You will also tend to be more universalistic, achievement-oriented, and specific.

Consider the following situation. A French manager was looking for partners in India. He hired a specialist in international business to help him. The international expert made several trips to India to identify the appropriate potential partners and to open the doors for the French manager. Each time the international expert was back in France reporting to him, the manager was unhappy because he believed nothing tangible was coming from so many trips to India. He would say, “We are spending a lot of money with your trips to India, and you always come back empty-handed.” Once the international expert had everything sorted out for the French manager’s first visit, he decided to go to India alone. He told the specialist, “You’ve been there several times and came back with nothing. I don’t need you there with me. I know how to handle it.”

Indians belong to a diffuse culture. This means they were at the airport waiting for their French guest when he landed. However, the French manager had already booked a limousine to take him to his hotel, which he had insisted upon using, rejecting the one suggested by his potential Indian counterparts. After the Indian hosts had waited long enough in the airport to understand that their guest had gone to the hotel by himself, they called him at his hotel to say they would pick him up for dinner. He replied, “If you want to have dinner with me, it should be in my hotel’s restaurant.” Needless to say, the Indians never arrived.

What happened? The hasty and arrogant approach of the Latin European is totally inconsistent with the humble and face-saving, long-term oriented Southeastern Asian values. What was carefully built across months by the international expert was destroyed in a couple of hours by the culturally unaware manager. What did he learn from the experience? Nothing. He believed that the international expert was incompetent and wasted a lot of money traveling to India, and that Indians are rude because they did not come to see him at his hotel when he had traveled to their country just to meet them.

The 10 Cultural Orientations Model

Walker and colleagues (Walker et al. 2003) define culture as a complex phenomenon that can be determined by three axioms:

•Axiom 1: Cultural boundaries are not national boundaries. Although it is easier to describe nations as cultures, and generalize behaviors, there are cultural commonalities across countries, and there are subcultures in each country.

•Axiom 2: Culture is a shared pattern of ideas, emotions, and behaviors. Cultures operate both in a conscious and unconscious level, and their characteristics are carried by groups and individuals.

•Axiom 3: Cultures reflect distinctive value orientations at various levels. The specificity of culture is that it lies in the difference between in and out groups. People who share the same culture sense that they are different from people who do not belong to that culture.

These authors created the 10 Cultural Orientations Model, which presents a framework of exploring and mapping components of culture at any level. It is the cornerstone of the cultural orientations approach and provides a common language and comprehensive lens for analyzing cultural phenomena and cross-cultural encounters. This set of cultural dimensions summarizes the main aspects that can explain cultural differences and cause misunderstandings in business settings. They are described in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5 The 10 cultural orientations

|

Cultural orientations |

Characteristics |

|

Environment |

Control/harmony/constraint |

|

Time |

Monochronic/polychronic, fixed/fluid, past/present/future |

|

Action |

Being/doing |

|

Communication |

High/low context, direct/indirect, formal/informal |

|

Space |

Private/public |

|

Power |

Hierarchy/equality |

|

Individualism |

Individualism/collectivism, universalism/particularism |

|

Competitiveness |

Competitive/cooperative |

|

Structure |

Order/flexibility |

|

Thinking |

Deductive/inductive, linear/systemic |

These cultural orientations permeate individuals’ professional and private lives. Knowing about them will help you to not only understand why people you will be negotiating with behave as they do, but also to anticipate some of their behaviors. Let’s analyze each of them.

Environment

Environment indicates a person’s basic relationship to the world at large. Negotiators who like to control the environment are more likely to rely on schedules and to avoid any surprises and improvisations. Anything that was not planned is very disturbing to them. Those looking for harmony with the environment will pretty much integrate it into their negotiations. They will try to control some aspects of it, such as time and weather, but are conscious of the fact that not everything is foreseeable. Finally, negotiators who see the environment as a constraint will let things happen and cope with them as long as they happen. To them, things just happen when they must, and there is nothing people can do other than conform to it.

Perhaps you have experienced the following situation. You are working with your Egyptian counterparts in their office in Cairo. Around 5:00 p.m., they tell you that it is time to leave because you are invited to a dinner at home of their company’s president. Your reaction might be, “Why didn’t you tell me about this before? I am not prepared!” Of course, if you say that, you will make your counterparts lose face. Instead, you go to the dinner wearing your work clothes and without knowing how much business you will talk about over the dinner.

This is the way things can happen in cultures where the environment dictates people’s lives. They are so used to taking life as it comes that they don’t even think about planning things in advance. Of course, they knew about the dinner long before your arrival in Egypt. But they wouldn’t let you know about it, because they would be going with you, and also because the dinner could have been cancelled at the last minute for any reason. So they just wait and see, and behave accordingly. The lesson is be prepared to never be prepared. You should always imagine that something you didn’t anticipate could happen, whatever it is. Just make sure you are ready to talk or not talk about business at unexpected moments with unexpected people.

Time

The use and views of time convey messages about what is valued in a given culture and how people relate to each other. We already described monochronic and polychronic people and how they manage time and tasks. Consistently, monochronic negotiators are punctual and scheduled. Time is fixed to them and being late looks un-businesslike. In addition, monochronic negotiators have a linear conception of time, and the past, present, and future do not mix.

In contrast, polychronic negotiators take their time to socialize and to conduct simultaneous activities. Time is fluid, and the definition of punctuality is subjective. Past, present, and future are not clearly dissociated, and negotiators may lose today to win tomorrow, because opportunities come and go across time.

If you work with Brazilians, you will experience authentic polychronic situations. First, all participants won’t be at the meeting at the same time. Brazilians make several appointments at the same time and juggle them. They take phone calls during the meetings and constantly go in and out of the room. If you are monochronic, you are more likely to feel lost and upset with these situations, since you believe every meeting has a starting and an ending time to be respected. You follow your agenda and have things done quickly, with all the people around the negotiation table at the same time.

Although it is sometimes overwhelming, you should plan more time when you work with polychronic people. Avoid making several meetings with different people the same day, as you never know what time your appointments will start and end. Moreover, your meetings may well end up moving to a restaurant, a bar, or another less formal setting. Once a delegation from the Netherlands in Brazil stood up at the time when the meeting was supposed to be over and rushed to their next meeting. However, for the Brazilians, the meeting was just starting. As a result, their negotiation with the Brazilians ended that very moment.

Action

Action focuses on the view of actions and interactions with people and ideas that tend to be expected, reinforced, and rewarded in a given culture. Negotiators belonging to a being culture value people’s personal and professional backgrounds. It is more important to be someone than to have accomplished important things in life. This means senior negotiators are more respected, the family and network are highly valued, and relationship is the bedrock of negotiation. It relates to what Trompenaars called ascription cultures.

On the opposite side of this dimension are achievement-oriented cultures. What you have accomplished as a professional counts much more than who you are. These cultures value experience more than diplomas and rely on facts and figures. Also, they respect confident negotiators with extensive field experience.

Take your résumé and show it to a negotiator from a doing (action-oriented) culture and to one from a being culture. They will focus on different aspects of your background. The doing-oriented negotiator will look at your jobs and accomplishments, versus the being-oriented negotiator, who will focus on your family name, your degrees, and your network. The first one will respect you because of your achievements; the second one values your personal traits.

Communication

There are different formats for expression and exchanging information. You have already seen the high and low communication context countries. High-context negotiators focus more on building relationship than on contracts and invest time in getting to know their counterparts personally. They stay away from direct communication, and part of their messages is indirect and nonverbal. These negotiators avoid conflicting situations and losing face. But the way they address you can be either formal—as with the Japanese—or informal—as with the Latin Americans.

Low-context negotiators are more time-oriented, get straight to the point, don’t need to get to know their counterparts personally to negotiate with them, and base their trust on contracts. They practice direct communication and can be either formal—like the Swiss—or informal—like Americans.

Another aspect of communication was introduced by Trompenaars through the neutral and affective dimension. Neutral negotiators are inexpressive and don’t use gestures or facial expressions to convey their messages. On the other hand, affective negotiators use emotions to convey either positive or negative messages. So neutral negotiators perceive affective counterparts as people who exaggerate, making a whole drama out of a simple argument. However, affective negotiators perceive neutrals as inhuman, cold, and inexpressive people. It is annoying to them to be unable to read their counterparts’ expressions to see whether or not they agree with what is being said.

Talk to the Chinese and you will have no clue of what they think about what you just said. They will not nod, they will not smile, and they will barely look at you. Ask them a question, and you will get no answer. Ask them if they understood what you said, and they will answer “yes.” You might feel very uncomfortable with their moments of silence, which will feel as if they last forever.

Then you fall into the traditional pitfall. You think that they didn’t understand what you said, and you rephrase, you add more information, and you give a more detailed explanation. Or worse, you think that they disagree and won’t say so openly. Then you hastily come up with other ideas or concessions as if they had make objections—which they haven’t. Silence and facial inexpressiveness are part of Chinese communication. There is nothing that you can do about it except to wait until they break the silence and continue the conversation. Silence is communication, so don’t interrupt it.

Space

Cultures can be categorized by the distinctions they make in their use and demarcation of space. If you belong to a culture where the space bubble is small, then you feel comfortable with physical closeness. Negotiators from these cultures tend to greet people with hugs, look for eye contact, and stand and sit close to each other. But if you belong to a culture where your bubble is bigger, then you might feel as if your privacy was invaded when others are too close.

The difficult aspect of this in negotiation is that in cultures where private and public spaces are mixed, people often feel rejected by those who step back when they greet them or talk to them. Scenes where one negotiator steps forward to talk and the other steps back at the same time might look hilarious to outsiders, but they are serious business to the one who feels rejected and the other who feels invaded.

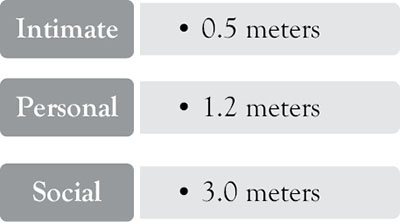

E. Hall is the cultural anthropologist who coined the term proxemics in 1963 (Hall 1963). He emphasized the impact of proxemic behavior (the use of space) on interpersonal communication. Hall believed that the value in studying proxemics comes from its use in evaluating not only the way people interact with others in daily life, but also the organization of space in their houses and buildings and, ultimately, the layout of their towns.

In cultures where physical closeness is appreciated, people might want to talk in places where you can sit side-by-side instead of the opposite sides of a desk or of a meeting room table. It might make negotiators feel more comfortable about delivering precious information. He defined three types of bubbles of space, as represented in Figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6 Personal bubbles of space as defined by Hall

Consider the following situation. You are queuing up somewhere in Cairo. Since your bubble of space is bigger than theirs, you keep some distance from the person in front of you. The Egyptian behind you asks you to step forward. You perceive this as getting too close to the person ahead of you without making the line move any faster. But if you don’t do that, some other people will take that tiny space and move you farther back in the line. You will not only feel physically uncomfortable but also upset with the rude Egyptians, who are unable to respect order of arrival and cheat openly before your eyes.

This example illustrates the business mentality of cultures where the bubble is small: all vacant places are to be taken before someone else does. When negotiating with them, make sure that you are not leaving any unfilled spaces both in your relationships and in your arguments, where someone else could sneak in.

Power

Hierarchy-oriented cultures value social stratification and accept differing degrees of power, status, and authority. Hierarchy has a clear impact on negotiators’ behaviors. The stronger the hierarchy, the weaker the negotiators’ autonomy to make decisions. Hofstede stated that hierarchy was a matter of power distance. In strong power distance cultures, there are several levels of management and negotiators are not allowed to report to upper levels, but only to their supervisors. They need approval for their actions as well as for concessions they can make during a negotiation. As a result, strong power distance tends to slow down negotiations, because negotiators’ ability to make decisions is restricted.

The consequences are easy to understand. If you are from a weak power distance culture, you may not be patient enough to wait until your counterparts get replies and approvals to keep going with the negotiation. As a more autonomous negotiator, you are able to make decisions by yourself and assume the consequences for these. You may even see their relationship with their manager as childish and may lose part of your motivation (or patience) to work with them.

A French manager hired an American negotiator to develop the company’s business with North America. The American negotiator believed he would work with the same level of responsibility and autonomy that he had in the United States. After 6 months, the American had developed no business at all. The French manager said that the American had no motivation. The American said that he never had a clear definition of his objectives as a negotiator, quit, and went back home.

What happened? The French manager never shared the whole project with the American negotiator. He supervised every action the negotiator took, more often than not telling the American that this was not the way he should work. The negotiator was lost, with no goals and autonomy, and wondered what his role was in such a company.

Individualism

Cultures differ in the way they value and perceive identity based on affiliation versus individual achievement. Both Hofstede and Trompenaars presented a cultural dimension measuring the degree of belongingness of an individual to a group.

In individualistic cultures, negotiators are more independent. They negotiate by themselves or in teams with a limited number of members. On the other side, collective negotiators create teams with several members, and each is assigned a specific role by the team leader. It is their obligation to measure the impact of the outcomes of their negotiation on the rest of their group. They have a clear idea of how much the group depends on them and how much they depend on their group. As an Australian negotiator once said after his first round with Koreans, “Next time, I will bring more people on our side too.”

It is worth noting that often the word individualism is confused with selfishness. That is far from truth. Individualistic countries are more communitarian, that is, individuals look after themselves but respect the rules to make sure they are not disturbing other individuals’ lives.

Collectivistic cultures tend to award privileges to and protect only their close groups. They don’t care about those whom they don’t know—even if they are part of the same community. You will also notice that people from individualistic cultures are more generous. They take more charitable actions and have the sense of giving back to the community, while in collectivistic cultures, people share what they have with the groups close to them.

Trompenaars adds the universalistic and particularistic cultural dimension. He stated that universalistic cultures are more egalitarian than particularistic cultures, because they apply the same rules to everybody. So universalistic negotiators will observe the company’s rules no matter whom they are negotiating with, while particularistic negotiators are more inclined to make exceptions depending on the person they are working with.

Rules are clearly stated, understood, and observed in universalistic cultures, while they are obscure in particularistic cultures, where favoritisms are frequent. If you are a universalistic negotiator, you constantly have the feeling that you missed something, such as a relevant bit of information. All of a sudden—and with no apparent reason—concessions that were impossible to do before turn out to be possible now, or vice versa. As there is a very strong attachment to the individual in particularistic cultures, negotiations are highly dependent on personal relationships between the counterparts. You need to become friends with them to get what you want.

An English negotiator went to Colombia. Although he could speak good Spanish, and his counterparts were fluent in English, the negotiation couldn’t work out—because he needed to stick to his company’s rules and make no exceptions. In addition, he could not understand the favors the Colombians were asking him for through indirect communication, because they were not clearly saying it. They used common expressions, such as “Now that we are friends, we can think differently. We are doing everything for you to feel comfortable among us.” His patterns of universality prevented him from being more customized in his negotiation. That led his Colombian counterparts to perceive him as too rigid.

Competitiveness

Competitiveness addresses deep drivers of action, choices, decision, and customs. Negotiators are always confronted with the cooperation or competitiveness dilemmas of their counterparts, as if they were obliged to choose one of them. It also relates to win-win (cooperative) and win-lose (competitive) negotiation strategies. Some cultures are more competitive because being excellent is the norm and competition is defined by being better today than yesterday.

Hofstede defines cultures as being masculine and feminine. Masculinity values competition, materialism, and professional achievement. Femininity draws on values such as harmony, cooperation, and general well-being. So competitive negotiators are more contract- and efficiency-oriented, while cooperative negotiators are more concerned about saving face and building long-term relationships.

Let’s say you are from a masculine country (and thus competitive) and you will be working with Swedish counterparts, who are very feminine. You would want to know that at the outset. Initially, you will feel comfortable because you might share some cultural dimensions, such as individualism, flat hierarchy, short-term orientation, universalism, and punctuality. This might lead you to negotiate with them in the same competitive way you would with a company back home. You will head right into a problem. The Swedish are extremely feminine, and harmony and equality are key characteristics of their culture. They will put their cards on table, wishing to build a winning situation for all—not only for the negotiating parties, but for everyone who could be directly or indirectly affected.

Structure

Structure recognizes different perspectives and attitudes toward change, risk, ambiguity, and uncertainty. Order has to do with being scheduled and rigid with time and tasks. Negotiators need to know about their schedules, meetings, topics to be treated, people participating in each meeting, and so forth. They wish to plan—as a way of avoiding uncertainty—and feel uncomfortable if plans change. They perceive this as a lack of professionalism and organization.

Negotiators from flexible structures are much less concerned about schedules, time management, and order. These people might take things as they come and are not disturbed by surprises because they are good at improvisation. They feel uncomfortable with a counterpart’s rigidity, perceiving him as a person who isn’t creative enough to cope with unplanned situations.

Assume that your Lebanese counterparts come to work with you in your home country. You’ve been working with two of them all afternoon and invite them to have dinner at 7:00 p.m. around 5:00 p.m., one of them tells you that he has another meeting and should leave. You are a bit disturbed but ask him if he will still join you for dinner. He says that he would be most happy to do so and asks you for the address to get to the restaurant. Once he has left, you want to keep going with the negotiation with your other counterpart. Then you realize no progress is being made because he is not the decision maker. Then you end up taking him to visit some of your building facilities and head to the restaurant for dinner.

At the restaurant, you order some drinks and tell the waiter that a third person will join you shortly, and that you will wait for him to order. Meanwhile, you keep socializing with your counterpart. At 7:50, you still don’t know where the other negotiator is—or even if he is coming to the restaurant. Your other counterpart seems fine about it.

Around 8:30, the other negotiator calls you to tell you that he will be there very shortly. After 30 minutes, he arrives and brings along the other person he has been working with until then. You end up having dinner with three other people, unable to talk about your business because of the unknown person at the table (who, by the way, you will never see again) and paying the bill for four people instead of three. As a result, you will need more time the next day to continue negotiating with them. This is how the people in unstructured cultures behave. Everything is possible, and flexibility is important to them. What you would have considered as being rude is just normal to them.

Thinking