Develop Individual Performance Measures for Leaders to Build Accountability

Tell me how you measure me and I will tell you how I’ll behave. Measurements drive behavior. If you do not have the right measurements, you have no right to expect the right behavior.

—Dr. Eli Goldratt

In the sequence of building the foundation for change, this is the final element to build after all other foundational elements have been developed. The reason why we do this at the end is because it provides leaders an opportunity to consider performance metrics that could arise from any of the previous foundational elements before finalizing the individual performance measures (IPMs), also commonly known as individual key performance indicators (KPIs) or individual key result areas (KRAs). In the words of Eiji Toyoda, former president and chairman of Toyota Motor Corporation, “Employees are offering a very important part of their own life to us. If we don’t use their time effectively, we are wasting their lives.”

It is common practice in many organizations to develop IPMs having a mix of quantitative and qualitative measures cascaded directly from the balanced scorecard or having project deliverables tied to an individual’s performance. Also, some organizations use an appraisal system based on employee job descriptions, a 360-degree feedback, employee engagement scores to formulate IPMs. This approach is good for delivering very specific short-term goals but not appropriate for the long haul, especially when transforming organizational culture is the mandate. Why? Because people express their values through personal behaviors and organizations express their values through cultural behaviors. A recent survey report published by Boston Consulting Group confirms that organizations driven by purpose and values outperform their competitors in revenue, profit, and stock performance. Jon Katzenbach, founder of the Katzenbach Centre, says, “Instead of changing culture significantly, it is much better to change the behaviors because they are more tangible and measurable. Cultures don’t change automatically, but they do tend to follow behavior change.”

While there is enough evidence to support the role of individual behavior in an organizational excellence and culture transformation, not much has been done to develop individual performance measures that promote ideal behavior to change organizational culture. Isadore Sharp, founder and chairman of Four Season Hotels and Resorts, said, “You can write the metrics on a paper, but they are only words … The words have significance only if behaved. Behaviors have significance only if believed.”

Before I share examples of IPMs developed for Hospital Heal to promote behavior change, I would like to share two popular models/frameworks and a scorecard template that focus on individual behavioral characteristics and leadership attributes for achieving enterprise excellence.

A.The Shingo Model™: Developed by the Shingo Institute, one of the pioneers in incorporating culture in their excellence model. The model provides the following three insights (Figure 26.1):

i.Ideal results require ideal behaviors

ii.Beliefs and systems drive behavior

iii.Principles inform ideal behavior

The Shingo Model™ of operational excellence is built on the foundation of cultural enablers that includes the principles of (1) lead with humility and (2) respect every individual—both qualities of a great organization. In the early 2000s, the philosopher Theodore Zeldin said, “When will we make the same breakthroughs in the way we treat each other as we have made in technology?” It is said that kindness is the language that the deaf can hear and the blind can see. The Shingo Model™ asserts that successful organizational transformation occurs when leaders understand and take personal responsibility for architecting a deep and abiding culture of continuous improvement. Leaders anchor the corporate mission, vision, and values in principles of operational excellence and help associates to connect and anchor their personal values in the same principles. They accelerate a transformation of thinking and behavior and therefore create a lasting culture of operational excellence. In his article on operational excellence, Robert Miller, former executive director of the Shingo Institute, says, “Improvement cannot be delegated down, organized into a program or trained into the people. Improvement requires more than the application of a new tool set or the power of a charismatic personality. Improvement requires the transformation of a culture to one where every single person is engaged every day in often small and from time to time, significant change.”

B.Competing Values Framework: Developed by Kim S. Cameron and Robert E. Quinn, both professors at the University of Michigan, for diagnosing and changing organizational culture, this framework provides a distinct set of skills for leaders and managers that are most effective in each of the four quadrants (Figure 26.2) for moving an organization to its desired culture. The framework has proven to be very robust in describing the core approaches to thinking, behaving, and organizing associated with human activity.

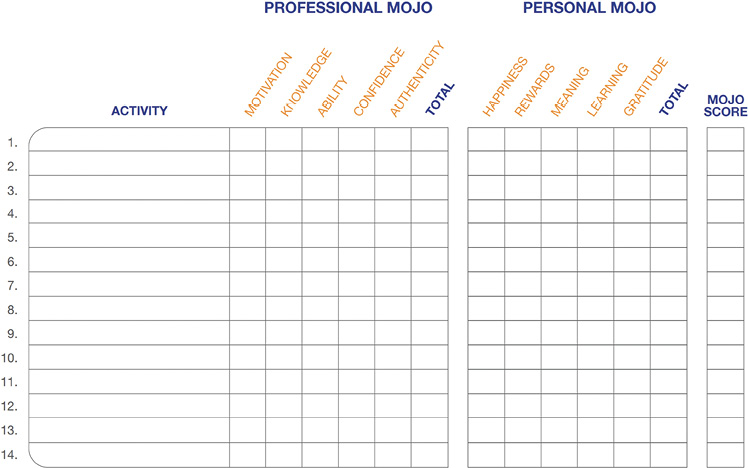

C.Marshall Goldsmith’s mojo scorecard: Dr. Marshall Goldsmith is one of the world’s leading executive educators and coaches. In his book, What Got You Here Won’t Get You There, he says, “People will do something—including changing their behavior—only if it can be demonstrated that doing so is in their own best interests as defined by their own values.” In his other book, Mojo, Marshall provides a scorecard that helps measure the two forms of mojo in our lives: professional mojo and personal mojo (Table 26.1). He defines mojo as the moment when we do something that’s purposeful, powerful, and positive and the rest of the world recognizes it.

Figure 26.2 Skills profile for leaders based on the Competing Values Framework. (Cameron, K.S. and R.E. Quinn. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010.)

The goal is to increase the overall mojo score (maximum 100), which is dependent on ten equally weighted elements, five elements each in the professional and personal categories as detailed below.

Elements of professional Mojo: What I bring to this activity

![]() Motivation: How engaged do I feel about the activity?

Motivation: How engaged do I feel about the activity?

![]() Knowledge: Do I understand what to do?

Knowledge: Do I understand what to do?

![]() Ability: Do I have the skills to do the task well?

Ability: Do I have the skills to do the task well?

![]() Confidence: How sure am I of myself?

Confidence: How sure am I of myself?

![]() Authenticity: Is my enthusiasm genuine?

Authenticity: Is my enthusiasm genuine?

Elements of personal Mojo: What this activity brings to me

![]() Happiness: Am I happy when engaged in this activity?

Happiness: Am I happy when engaged in this activity?

![]() Reward: Does this activity provide me with material or emotional rewards?

Reward: Does this activity provide me with material or emotional rewards?

![]() Meaning: Are the results of this activity meaningful to me?

Meaning: Are the results of this activity meaningful to me?

![]() Learning: Does this activity help me learn and grow?

Learning: Does this activity help me learn and grow?

![]() Gratitude: Do I feel grateful for this activity, and is it a great use of my time?

Gratitude: Do I feel grateful for this activity, and is it a great use of my time?

It is a good tool to validate and prioritize your daily activities. Used creatively, you can replace the activities with management system elements in an excellence journey and check the mojo score for your leaders and their teams.

The guidelines and frameworks shared above are examples to trigger the reader’s thinking process for identifying measures and developing IPMs that build accountability and to inspire the leadership mindset, “Improving the work is the work.”

Excellence is an art won by training and habituation. We do not act rightly because we have virtue or excellence, but we rather have those because we have acted rightly. We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.

—Aristotle

Transformational change is more than fine-tuning the status quo with a redesign of systems and processes. Transformational change requires people to reframe how they think about and perceive their roles, responsibilities, and relationships. Having IPMs designed around the balanced scorecard outcome measures makes it merely an act, visited only a few times in a year, and does not hold leaders accountable to repeat the act on a daily basis to make it a habit. As Jalal ad-Din Rumi said, “Yesterday I was clever, so I wanted to change the world. Today I am wise, so I am changing myself.”

Table 26.2 provides examples of the IPMs developed for the leaders at Hospital Heal that promoted behavior change. After considering several options, elements of the management system were chosen to operationalize the desired behaviors for creating a new culture. The measures were integrated with their recognition and development review (RDR) appraisal system, and continuous coaching and feedback interactions replaced biennial (once in two years) formal reviews.

Table 26.2 Example of Individual Performance Measures for Leaders at Hospital Heal

Sensei Gyaan: Undertake culture assessment. Find the gap between the current state and the desired future state of culture. Leverage strengths of your current culture and identify behavioral characteristics that support in implementing your organizational strategy. Think KBI (Key Behavior Indicators) vs KPI (Key Performance Indicators). Select KBIs that support those behavioral characteristics to get the desired results.