CHAPTER 2

THREE CROSS-CULTURAL COMPETENCIES AFFECTING CULTURALLY AGILE RESPONSES

In 2001, the British-Dutch conglomerate Unilever bought the American Vermont-based ice cream manufacturer Ben & Jerry’s. A key asset of Ben & Jerry’s was its market niche among those customers who appreciated the premium ice cream with unusual flavor names like Karamel Sutra, Chocolate Therapy, and Imagine Whirled Peace. In the acquisition, Unilever needed to preserve this market niche, which was based in no small part on the corporate image of Ben & Jerry’s social responsibility and left-leaning social activism. With an image honed by the founders Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield over almost twenty years, Ben & Jerry’s worked with sustainable, Fair Trade certified and organic suppliers; used environmentally friendly packaging; paid premium prices to dairy farmers from Vermont who did not give their cows growth hormones; and created business opportunities for depressed areas and disadvantaged people. Giving 7.5 percent of their pretax revenues to charity, publicly traded Ben & Jerry’s could not be accused of corporate greed. At the time of the acquisition, however, the Ben & Jerry’s alternative management style lacked the fiscal and managerial discipline market analysts and investors demanded. The company’s stock had fallen from almost $34 in 1993 to $17 in 1999.

Enter Unilever and Yves Couette, Unilever’s choice to be the CEO of its new oddball acquisition.1 As a longtime corporate Unilever executive, the French-born Couette had spent several years running businesses in Mexico and India. Couette needed to thread the proverbial needle as the CEO, to understand this alternative American organization enough to preserve the intangible assets of Unilever’s new acquisition while at the same time introducing some parent-company fiscal and managerial controls.

Within his first few months as CEO (an acronym that at Ben and Jerry’s means chief euphoria officer), Couette demonstrated his true cultural agility by adapting some—but not all—of his leadership style and business practices.2 He began with symbolic gestures. He came to work dressed casually, and volunteered to mix mulch at a company-sponsored gardening project in the local community. These initial gestures helped build rapport and ease employees’ concern that Couette was sent by Unilever to dissolve Ben & Jerry’s small-town American (and anticorporate) culture. On a more tangible level, Couette also continued the corporate social responsibility approach of the founders, saying that he envisioned Ben & Jerry’s to be “a grain of sand in the eye of Unilever” because these practices were more generous than those typically found in publicly traded companies.

Even after the Unilever takeover, the core of Ben & Jerry’s values remain. The company continues to contribute about $1.1 million annually through employee-led corporate philanthropy and makes substantial product donations to community groups.3 Today, Ben & Jerry’s press releases reinforce this commitment to “doing good,” stating that “the purpose of Ben & Jerry’s philanthropy is to support the founding values of the company: economic and social justice, environmental restoration and peace through understanding, and to support our Vermont communities.” Under Couette’s leadership through the postacquisition transition, the Ben & Jerry’s external mission continued.

However, Couette knew that some things needed to change at Ben & Jerry’s to deliver a financial return to Unilever. In a very un–Ben & Jerry’s act, he downsized the company—eliminating jobs and closing plants. He provided structure and introduced some basic organizational practices, and opened Ben & Jerry’s positions to Unilever’s global talent pool. Knowing that these moves would be unpopular with the employees, he justified them by saying that “the best way to spread Ben & Jerry’s enlightened ethic throughout the business world was to make the company successful.”4

There was also an integration of the Ben & Jerry’s practices with those of Unilever. For example, Ben & Jerry’s began using the Unilever performance management system—but added its own performance dimension of maintaining the company’s social mission. Many would agree that in this critical postacquisition integration phase, Couette successfully led Ben & Jerry’s both to maintain its corporate identity and brand image and, at the same time, to become profitable.

THE CULTURAL AGILITY COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK: TWELVE KEY COMPETENCIES

It was not by accident that Yves Couette, a highly culturally agile professional, was able to navigate the myriad of cultural challenges embedded in the Ben & Jerry’s acquisition. Over years of working in different environments around the world, Couette has honed cross-cultural competencies enviable in many global organizations today. Unfortunately, there aren’t enough culturally agile professionals who share his competencies. In a survey conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit, more than four hundred global business executives were asked to name the primary shortcomings of management-level and other specialized workers in various markets around the world.5 Three of the top four areas of concern were competencies related to cross-cultural agility: limited creativity in overcoming challenges, limited experience within a multinational organization, and culture-related issues. The report concluded that “many candidates do not yet possess the understanding and sensitivity to navigate the intricate internal politics of a global organization or deal with the very different cultural backgrounds of a diverse workforce.” Karl-Heinz Oehler, vice president of global talent management at the Hertz Corporation, offered this insight on the findings in this report: “The rarest personality traits are resilience, adaptability, intellectual agility, versatility—in other words, the ability to deal with a changing situation and not get paralyzed by it.”

Research and practice have identified certain cross-cultural competencies that enable professionals to assess cross-cultural situations accurately and operate effectively within them. The twelve most critical of these cross-cultural competencies constitute the Cultural Agility Competency Framework. Although the framework is not an exhaustive list of cross-cultural competencies, these are the competencies I consider to be the most important because they are the ones with the greatest validity evidence—with demonstrated relationships to success in diverse international, cross-cultural, and multicultural roles. Please take a moment to review the Cultural Agility Competency Framework (see box on page 25) and judge for yourself which competencies make the greatest amount of sense for your organization’s strategic needs.

HOW THE COMPETENCIES AFFECTING BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES ARE DIFFERENT

The three cross-cultural competencies affecting behavioral responses—cultural minimization, cultural adaptation, and cultural integration—are different from the other nine competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework. Those other cross-cultural competencies (to be discussed in detail in Chapter Three) operate from a human talent approach which posits that their presence in global professionals is good and that a greater level of the competencies is related to a higher degree of cultural agility—in short, more is better. We have research and cases to show a direct relationship between their presence and subsequent professional successes in cross-cultural settings.

But in the case of cultural minimization, cultural adaptation, and cultural integration, the pattern for success changes: the presence of these three cross-cultural competencies is good when they are leveraged at the appropriate times. Unlike the other cross-cultural competencies, these three are not simply “nice-to-haves.” Global professionals must be able to use these competencies correctly to increase their overall cultural agility. For example, cultural minimization is potentially derailing for global professionals in circumstances where some level of cultural sensitivity is needed; in those circumstances, inattention to the effect of culture will be detrimental to the outcome. Similarly, leveraging cultural adaptation at the wrong time can result in professionals’ overinterpreting behaviors on the basis of cultural expectations or nationality. And using cultural integration at the wrong time can run the risk of taking too much time to build consensus, especially in situations where it would be appropriate to use either the organization’s approach or the local approach.

COMPETENCIES AFFECTING BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES IN CROSS-CULTURAL CONTEXTS

Successful global professionals like Yves Couette know that cultural agility comprises more than just cultural adaptation; however, there are times when adapting to the norms and behaviors of the local context is essential. They know they cannot ignore cultural differences; however, there are times when cultural minimization is needed—when a higher-order professional demand will supersede cultural expectations and make it necessary to override a cultural norm. They know that merging multiple cultures to create a new set of behavioral norms can be time consuming and challenging—but there are times when cultural integration is most important and well worth the effort. Successful culturally agile professionals decide which approach or orientation to cultural differences is needed, and behave accordingly. Having these three competencies available as plausible responses is akin to having multiple tools in the proverbial toolbox. The most cultural agile professionals have a command of each of these orientations and can leverage them as needed, depending on the situation in which these professionals are operating.

James Piecowye, a Canadian culturally agile professional, has been an associate professor in the College of Communication and Media Sciences at Zayed University in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, since 2000. James knows exactly what it means to toggle among these three cultural orientations, something he had been doing long before he even left Canada. James, who is originally from Ajax, Ontario, an English-speaking part of Canada, pursued his doctoral degree at the University of Montreal, a French-language institution in Quebec.

James credits this experience living in French-speaking Quebec with laying the foundation for his cultural agility; he quickly learned that his French language acquisition, while challenging, was merely providing the means to deliver far deeper cultural challenges. Staying in Montreal for fifteen years, James learned to toggle effectively among the three cultural orientations. For example, he earned the trust of his French-speaking colleagues in the quintessentially French manner—slowly, over time. The more time he invested in building professional relationships and adapting to the French culture, the more his French-speaking colleagues accepted him, eventually even speaking with him in English. At the same time, he wrote in English and adopted the broader English-speaking Canadian norms for conducting his research, even though they were not typical among his French-speaking colleagues.

Now living and working in Dubai, James notes similarities between the United Arab Emirati and French Canadian cultures: “There is more of a community and communal aspect to the French Canadian culture that I don’t think exists anywhere else in Canada. In a sense, the French Canadian culture is more like the tribal culture of the United Arab Emirates.” As he is quick to add, however, “moving to the UAE was a huge cultural change—not just the Arab culture but also the expatriate culture with its mix of Indians, Pakistanis, Europeans, Australians, North Americans, and Asians. It was an extreme experience.” James reconciled the cultural challenges and embraced the opportunities in the UAE, again negotiating with his multiple cultural orientations.

James is a male professor in an accredited university in Dubai that teaches only Arab women. He brings cultural minimization into the classroom by maintaining his standards and expectations for his students’ learning. Suspending his judgments, James uses cultural adaptation and adjusts his behaviors to accommodate the more collectivist Emirati ways, which are rooted in their Arab culture and predominantly Islamic religion. He uses cultural integration also, starting with the ideas that he and his students share a common desire to learn and that the best way to learn is to collectively create an interactive environment where students can comfortably share their experiences. James calls it “meeting in the middle.”

Over the past six years, James has also been a radio host on DubaiEye (103.8 FM), which describes itself as “Dubai’s premier talk radio station” and offers broadcasting twenty-four hours a day in eight languages. Its listeners include expatriates from some forty countries. Again showing his cultural agility, James works with British, Australian, South African, and Filipino presenters at the station. “What makes the relationship work,” he says, “is that we are all working toward the same goal to create informative, compelling, and enjoyable radio. The fact that each of our countries may have a different radio culture is of little consequence. What is important is that we all agree to work collaboratively in an environment different from our own—one that does not have legislated freedom of the press or even a long radio culture.”

As a culturally agile professional, James selects a particular cultural orientation intentionally. For example, he does not have a maid or a gardener, opting to eschew the symbols of class status that his profession and income give him in the traditionally hierarchical culture of the UAE. James initially predicted that as a result of his countercultural behavior, he would receive less respect from the laborers in the neighborhood. (He thought, at the time, that it was a very small price to pay to maintain the pleasure he experiences when tending to his garden and washing his car.) In fact, the opposite occurred: the neighborhood gardeners and maids respect James tremendously because, as a person of status doing their jobs, he elevates their own positions through his actions, and they appreciate the respect James gives them. In reflecting on his own career and the careers of his colleagues with cultural agility, James shares that cultural agility “does not mean people either agree fully or give up their own cultural norms, but it does suggest that they are able to look beyond the differences and work toward common goals—goals which will invariably be influenced by and rooted in the local host culture.” As his comment reflects, James operates with an authentic respect for other cultures while maintaining a healthy sense of self.

As a professor and popular radio host, James has achieved the success that accrues to culturally agile professionals who operate with multiple available behavioral responses, leveraged appropriately depending on the requirements of the professional situations. They will use cultural minimization when the situation demands that their behaviors supersede the local context. They will adapt their behaviors when the situation demands attention to the local context. They will also create a new behavioral set, taking elements from multiple cultural contexts.

In a study of more than two hundred global professionals and international assignees from more than forty countries, Ibraiz Tarique and I found that those who possessed a greater number of available cultural responses earned higher ratings from their supervisors on “how effectively they work with colleagues from different cultures.” Figure 2.1 illustrates this result.

FIGURE 2.1. Number of Available Cultural Orientations and Ratings of Global Professionals’ Ability to Work Effectively with Colleagues from Different Cultures

The given global context of the job, task, or professional role is what matters most when deciding which behaviors are the most appropriate for success, whether one should behave with cultural adaptation, cultural minimization, or cultural integration. As shown earlier, these three make up the behavioral responses in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework. Figure 2.2 provides a definition of each of these competencies.

FIGURE 2.2. Competencies Affecting Behavioral Responses

In the remainder of this chapter, I will examine each of these three competencies with examples from various sectors of the business world. Although all three are essential for success as a global professional, each is especially crucial—and effective—in certain areas, including the following:

- Health and safety

- Quality assurance

- Strategic company-wide practices (especially those considered key to competitive advantage)

- Global image or brand

- Sales and marketing

- Government relations

- Working with regulatory agencies

- Local-level manufacturing operations

- Global teams

- Joint ventures

- Postacquisition or postmerger integration

- Negotiations

Cultural Adaptation

Culturally agile professionals are able to navigate the differences in cultural norms and behaviors and to adjust—when needed—to be successful. As a culturally agile business leader, Yves Couette adapted his management style and organizational decisions to fit with the alternative, antiestablishment norm of Ben & Jerry’s to gain trust and build credibility with Ben & Jerry’s employees. There are many roles, tasks, and positions where adaptation to the demands of the host culture or another individual’s culture is needed in order for a professional to be successful. Activities where professionals need to work with influential national institutions, such as a country’s government or regulatory agencies, require cultural adaption to accommodate a different set of rules, regulations, and laws. Activities involving product development and design, especially in such areas as fashion and food, also require cultural adaptation to understand and accommodate differences in taste and preferences. Activities in which the goal supersedes the process for achieving it might also require cultural adaptation, such as maintaining local preferences for production facilities in situations where doing so would not negatively affect the outcome. Likewise, sales, marketing, and customer service roles require cultural adaptation to develop the client relationship, build trust and credibility with the client, and meet the client’s expectations.

There are many roles, tasks, and positions where adaptation to the demands of the host culture or another individual’s culture is needed in order for a professional to be successful.

Cultural Adaptation and Client Development

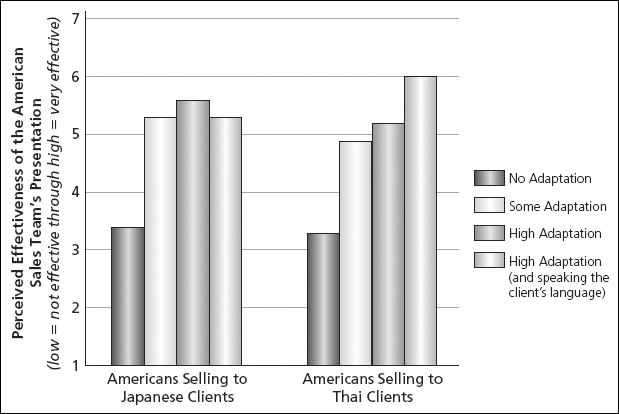

In the case of sales and client development, the person who is selling will, most often, need to adapt to the buyer’s culture in order to be perceived as credible and trustworthy—and, ultimately, to be successful. To illustrate this professional demand, researcher Chanthika Pornpitakpan assessed the reactions of Japanese and Thai “buyers” to American “sellers” in a sales context.6 She found that in the scenarios where the Americans adapted their behaviors to be more consistent with the cultural expectations of their Japanese and Thai clients, they were perceived more favorably. The American sales team members were perceived as more attractive sellers (for example, likable, comfortable to deal with) and had better anticipated outcomes of their sales presentation (for example, being granted a sales contract or considered for future sales) when they exhibited at least some level of cultural adaptation. For example, the Thais perceived the American sales team members more favorably and anticipated a better sales outcome when the Americans wore Thai suits (for example, Chut Phra Rachatan), accepted invitations to lunch, addressed them as “Khun” followed by first names, and used less expressive gestures. The Japanese perceived the American sales team members more favorably and anticipated a better sales outcome when the Americans used the Japanese style of exchanging business cards, spent time building the relationship before doing business, and addressed them with the title “Buchoo.” Figure 2.3 illustrates the differences among how the American sales teams were perceived under the different scenarios of adaptation.

FIGURE 2.3. Level of Americans’ Adaptation to Thai and Japanese Cultures and the Americans’ Perceived Effectiveness by Their Thai and Japanese Clients

Source: Data from Chantihika Pornpitakpan, “The Effects of Cultural Adaptation on Business Relationships: Americans Selling to Japanese and Thais,” Journal of International Business Studies 30, no. 2 (1999), pp. 317–337.

Adaptation of even the most basic behaviors can feel awkward at first. It might even feel disingenuous or “phony” to use the behavioral norms of another culture. Chanthika tested this by asking the Thai and Japanese “buyers” whether they perceived the Americans’ attempt to adapt to their cultural norms as derogatory. Overwhelmingly, the Thai and Japanese clients perceived the adapters as “not at all” derogating their cultural identity. In other words, in the sales setting, there was no downside—beyond feeling a bit awkward at first—for sales representatives trying to adapt their behaviors to be culturally consistent with those of the client.

Chris Houghtaling understands firsthand the benefit of some cultural adaptation to the sales situation. Chris is an American currently living in Vienna, Austria, where he lectures in sales for the University of Applied Sciences, Wiener Neustadt. Chris is a culturally agile sales and marketing professional who, in 1999, completed his International MBA through the University of South Carolina’s Darla Moore School of Business with a joint degree from the Executive Academy at the Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, one of Austria’s leading business schools. According to U.S. News & World Report, this program has been ranked among the top three among International MBA programs for the past twenty-two years.7 For the past twelve years, since graduating with his International MBA, Chris has been working in sales, leveraging his cross-cultural competencies to increase his success.

Prior to starting his International MBA, Chris recalls being attracted to an international career while working for USRobotics Corporation (USR). As part of USR’s new U.S. government sales team, Chris established an Internet presence for U.S. government agencies located outside the United States to gather product information and obtain pricing from government-approved resellers. This required him to coordinate with internal and external partners worldwide. He enjoyed working with people from different cultures, observing different professional styles and approaches to business. After completing his International MBA, learning German, and working in Vienna for a couple of years, Chris relocated back to the United States and began a successful career in pharmaceutical sales. Within the first year, he turned around a territory that traditionally performed in the bottom 25 percent to become a top 20 percent territory.

In 2005, while working in northern Virginia, Chris tried a practical experiment with Ken Sharan, a colleague from India who was working in the Baltimore, Maryland, area. With the goal of improving their sales performance, they leveraged what they knew about cultural differences to develop better and deeper client relationships with foreign-born doctors by adapting their relationship-building styles to their clients’ cultures.

Chris, who was doing frontline sales with clients ranging from general practitioners to infectious disease and pulmonary specialists to hospital administrators, found that subtle and sincere cultural adaptations were viewed positively. He developed relationships with his clients who were Chinese nationals by researching facts and ideas from China’s rich medical history and discussing them with the Chinese physicians. To connect with his physician clientele from India, he learned about the various regions and religions of their diverse country. With sincere interest, he was able to establish a more open dialogue, better accommodate his clients, and build deeper relationships. For example, he could suggest more appropriate regional or vegetarian restaurants for business meetings; he could also incorporate his clients’ religious and national holidays into his sales planning and scheduling. Chris wished his Chinese physicians “Happy New Year” around the Chinese New Year and his Indian physicians “Happy Diwali” or “Happy Holi” at the appropriate times. These small gestures signaled to his customers that he cared about them and not just about making sales. His sincere interest in his clients’ cultures and his small culturally adaptive gestures made a big difference. Chris saw his sales dramatically increase among his culturally diverse clients. Among this group of clients, Chris’s market share jumped from 8.7 percent to 18.4 percent within six months, and the success was sustained over time. Ken enjoyed similar success.

Chris learned a lot from his and Ken’s practical experiment on the power of cultural adaptation. As he observed,

Sales professionals know that to be good at what you do, you need to approach each customer to learn what their needs, objections, and buying triggers are. However, with the strategy of standardizing marketing messages that is taking place in many organizations, there is pressure from companies to follow the standardized sales message and presentation, regardless of the customer. This causes sales professionals to become distracted from what they do best, building meaningful relationships that positively impact business . . . In the majority of the world, building relationships with your customers is much more important than in the U.S. Gaining trust and respect on a personal level before you can start to sell your product comes before making a smooth sales presentation.

The advice Chris offers resonates among culturally agile sales professionals. It is important to concurrently standardize marketing messages, integrate the various motivators for clients to purchase (that is, their buying triggers), and adapt the relationship to the clients’ cultural differences. In the case of client development, the latter is particularly critical. With that in mind, Chris offers advice to other sales professionals and organizations working across cultures:

First, organizations and sales professionals need to evaluate if they are open to adjusting themselves, their style, and their messaging for each customer and if they are willing to put this openness into practice. The second is that companies and sales professionals need to recognize the fact that people from another country do not leave their social norms and values behind when they move, and it is to everyone’s benefit to incorporate some of your customer’s social norms and values into your sales activities. Although this may feel unnatural to the salesperson, when done with honesty toward the person to whom you are directing your cultural openness, and not the sale, the customer will, in most cases, appreciate the effort and recognition.

As Chris notes, this adaptation might feel unnatural or awkward at first, but it will be the key to success in the long run. Aside from the initial awkwardness, adapting one’s surface-level cultural behaviors—mixing mulch or washing one’s own car, wearing certain clothes, selecting appropriate restaurants, exchanging business cards, remembering to greet a customer on certain holidays—should be relatively straightforward for most global professionals. Most can make these cultural adaptations, muddling through those unfamiliar surface behaviors at first (the kisses, the firm handshakes, the bows) to feel less self-conscious and more comfortable with practice. The greater challenges for global professionals tend not to be in adapting to surface behaviors when needed; they lie in adapting to deeper aspects of a different culture, such as the differences in work practices, attitudes and values, and, at times, ethical norms.

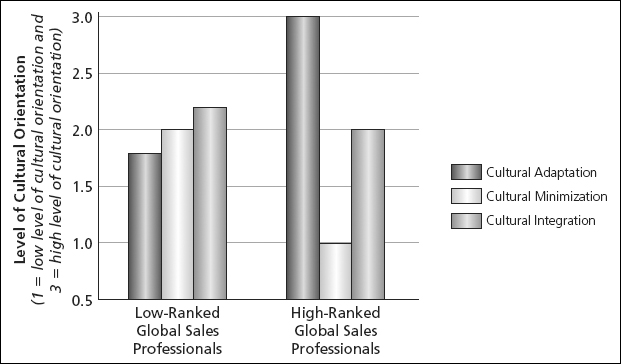

My research concurs with the experiences Chris shared. When fifty global sales professionals were rated by their supervisors on their effectiveness in interacting with clients from different countries, those with a higher level of cultural adaptation were more effective compared to those with a lower level. As Figure 2.4 illustrates, adaptation is related to success with clients.

FIGURE 2.4. Effectiveness of Sales Professionals and Their Cultural Orientations

Cultural Adaptation in Manufacturing

This is all very well for professionals in sales, where “the customer is always right.” But what about cultural adaptation in other sectors of the business world? Let’s consider the possible adaptations needed among professionals in the manufacturing industry. At first glance, these roles for operations professionals might seem culture-free because there are robust universal common goals for production facilities: everywhere, production facilities hope to increase productivity, quality, safety, and efficiency while reducing waste, time, inventory, and injury. The goals might be common, but how operations professionals motivate workers to achieve those goals will often need to be adapted to the local culture.

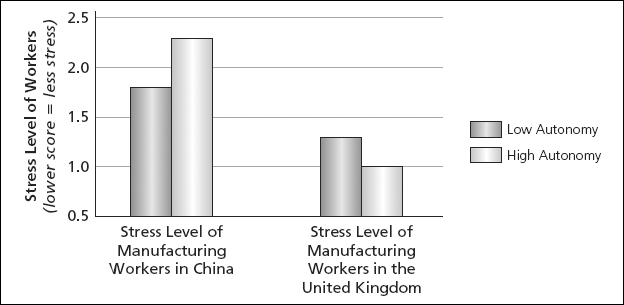

A study by the Australian researcher Giles Hirst and his colleagues compared predictors of productivity in manufacturing facilities in the United Kingdom and China.8 Specifically, they examined the effect on workers’ stress levels of the practice of empowering workers by giving them greater autonomy, discretion to make decisions, and control over their work. The production workers from the United Kingdom felt less stress as the result of being given greater autonomy. However, the experience for the production workers in China was the direct opposite: they experienced more stress from the same practice, given their cultural preference for directive leadership. This is relevant to productivity because Giles found in both countries that productivity decreased when workers felt that the demands on them were particularly high. Stress can exacerbate the problem of interpreting work demands. Figure 2.5 illustrates this finding.

FIGURE 2.5. The Difference Between British and Chinese Workers’ Reactions to Being Given Autonomy

Source: Data from Giles Hirst and others, “Cross-Cultural Variations in Climate for Autonomy, Stress and Organizational Productivity Relationships: A Comparison of Chinese and UK Manufacturing Organizations,” Journal of International Business Studies 39, no. 8 (2008): 1343–1358.

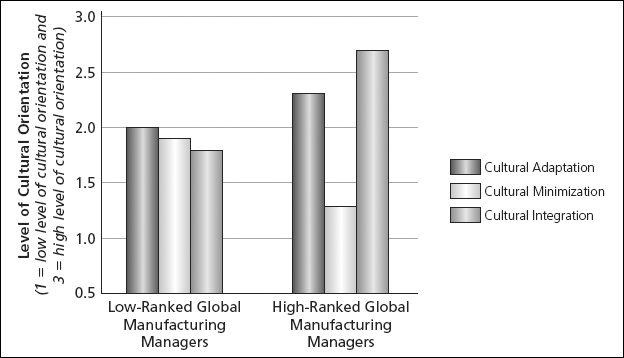

In a study I conducted with Ibraiz Tarique, about ninety global manufacturing managers were rated by their supervisors on their effectiveness in supervising people from different countries. In further analysis of these data, I found that the manufacturing managers with higher levels of cultural adaptation and cultural integration were more effective than those with lower levels of these orientations.9 As Figure 2.6 illustrates, being able to both adapt and compromise, when needed, is related to success when supervising subordinates in a cross-cultural manufacturing capacity.

FIGURE 2.6. Effectiveness of Manufacturing Professionals and Their Cultural Orientations

Cultural Adaptation in Government

Sales and manufacturing are not the only sectors where cultural differences will affect the outcome of professionals’ activities. Shung Shin, Frederick Morgeson, and Michael Campion studied 910 midcareer American professionals who were working for an international agency of the U.S. government.10 They worked in public relations, as economic analysts, as political analysts, and in other such positions and were expected to spend two-thirds of their tenure with the agency working in international posts. As a result, the professionals in the study were well-seasoned global professionals. Shung, Frederick, and Michael found that although the overall duties of these professionals did not change as a function of being relocated, the way in which they performed their duties did. For example, when these professionals were in more collectivist or group-oriented countries, they performed more relationship-oriented tasks, such as teaching; coaching others; and coordinating, developing, and building teams. They performed these tasks less frequently in more individualistic cultures.

Cultural Adaptation’s Major Challenge: Ethical Dilemmas

The government example we’ve just discussed illustrates how professionals might need to adapt the way they work in order to be effective in another culture. The previous examples illustrate how culturally agile professionals might need to adapt certain practices in order to be successful in their role. But what if we delve deeper into the interpretation of behaviors from the perspective of one’s values—and how those interpretations might vary in different cultural contexts? I’m not saying that individuals’ values themselves would change—but that the global professionals’ interpretations of behaviors might vary with a broader understanding of the demands of the international or multicultural situation. Before working globally, a professional might judge a certain norm or practice as inappropriate, wrong, inefficient, or even unethical—but might revise that initial impression after fully understanding the context. For example, in some countries it is appropriate to hire one’s family members to fill key positions in one’s organization. In many Western cultures, this nepotism might be seen as a corrupt or inappropriate form of favoritism. But in many Eastern cultures, the person you can trust the most to work hard for you would be someone who is a family member.

In some situations there will be a (more or less) universally accepted interpretation of behaviors that are appropriate or inappropriate, right or wrong, efficient or inefficient, and ethical or unethical. Other times, the interpretation will need to pass through a culturally agile lens—one where the context is fully understood. Culturally agile professionals can more readily differentiate between situations where a local practice violates universally accepted norms, and situations where cultural adaptation is warranted.

Andrew Spicer, Thomas Dunfee, and Wendy Bailey compared seasoned global professionals—Americans who were living and working in Russia—with comparably placed American professionals who were working in America.11 The two groups did not differ in their attitudes and intended behaviors in scenarios involving universally accepted ethical norms, such as failing to inform employees about the physical risk from exposure to hazardous materials, or investing money in capital equipment instead of paying wages. Personally, I was relieved to learn that all of the American professionals in their study—whether working in Russia or America—viewed these behaviors as immoral, unfair, and unjust.

When the scenarios turned to more situation-specific norms, however, the attitudes toward the situation and their intended behaviors in the situation changed depending on the group. The Americans working in Russia evaluated locally specific ethical dilemmas, such as paying small bribes to a government official or keeping two sets of books for different accounting purposes, less harshly than did their compatriot counterparts working in the United States. Although they still viewed these practices as generally unethical, those working in Russia exhibited attitudes and intended behaviors that were more consistent with the Russian norm, not judging them as seriously unethical. Figure 2.7 illustrates this finding. With their experience in Russia, they judged the scenarios with a greater understanding of the local demands and context. We could stop here and debate whether keeping two sets of books, for example, should be universally unethical. But let’s change the lens a bit. The authors noted that the two sets of accounting books—which is unethical in many contexts—might be reframed when the practice is needed in order to keep financial information secret from those involved in organized crime. This is a cultural interpretation that the Americans working in the United States would never have needed to consider—at least, I hope not!

FIGURE 2.7. Responses to Ethical Dilemmas

Source: Data from Andrew Spicer, Thomas Dunfee, and Wendy Bailey, “Does National Context Matter in Ethical Decision Making? An Empirical Test of Integrative Social Contracts Theory,” Academy of Management Journal 47, no. 4 (2004), 610–620.

Cultural Minimization

It’s probably safe to assume that every organization has certain practices it would like to see maintained consistently around the world. Health and safety standards, codes of conduct, quality standards, fiscal controls, corporate values, and codes of ethics are typical examples of activities that companies typically wish to standardize and control around the world. Global professionals with responsibilities for these areas often are asked to shape and influence the behaviors of colleagues, vendors, suppliers, associates, and subordinates to fit with a corporate or industry norm. In these areas (for example, safety, ethics, and quality assurance), global professionals often need to operate with cultural minimization, working to override any cultural differences and ensure a common standard or outcome. But minimizing differences is often easier said than done. In order to accomplish it, global professionals need to concurrently see (and understand) the cross-cultural differences, and influence others to change or adapt their behaviors. That last sentence has two important moving pieces: (1) an understanding of cultural differences in the desired behavior, and (2) an understanding of how to successfully influence behavior. Cultural minimization is not as easy as it seems—not by a long shot.

Global professionals often need to operate with cultural minimization, working to override any cultural differences and ensure a common standard or outcome.

Cultural Minimization in Health and Safety Practices

To understand the way culturally agile professionals minimize cultural differences, let’s consider safety policies and practices. In this realm, the desired behaviors are relatively clear and objective. You can probably envision the posters in the lunch room: “Are you wearing your safety goggles?” “Is your mobile phone turned off when operating machinery?”

Maddy Janssens, Jeanne Brett, and Frank Smith conducted a study of the adoption of corporation-wide safety practices among production workers in three comparable subsidiary manufacturing plants, one each in the United States, France, and Argentina.12 Although the policy was the same for the subsidiaries, the production workers from the three countries perceived the same U.S.-based safety policy very differently. For the Argentinian workers, their perception of the importance of the safety policies was deeply connected with their perception of their managers’ concern for their safety (as opposed to a concern for production). The French workers, in contrast, made little connection between their managers’ concern for their safety and whether safety was a priority in the organization. Now imagine that a well-intentioned senior leader from the U.S. headquarters is visiting each subsidiary to give an impassioned speech outlining the company’s safety practices and emphasizing how much he cares about everyone’s safety, over production. The same speech would be likely to motivate the Argentinian workers to follow safety procedures—while producing bored eye-rolls among the French workers.

Let’s stay with safety speeches for a moment. Shell is the world’s leading oil and gas company, describing itself on its Web site as a company with health and safety as its “top priority.” Shell’s safety practices are tightly controlled and allow for no variation, irrespective of culture. In 2007, Shell appointed Darwin Silalahi as country chairman and CEO of Shell Indonesia.13 With educational experiences including a degree in physics from the University of Indonesia; an MBA from the University of Houston; an executive education program at Harvard; and years of work experiences at BP, the Indonesian Office of the State, and as the Indonesia Country CEO for Booz Allen Hamilton, Silalahi was the first Indonesian to hold this senior-most position at Shell Indonesia.

In a speech to his Indonesian subsidiary encouraging adherence to Shell’s strict safety practices in Indonesia, Silalahi emphasized the policy but added a collectivist spin, one he knew would resonate among his group-oriented Indonesian workers: “At Shell, we believe we are all safety leaders. What each of us does individually results in our collective culture. We must each take personal responsibility for creating a culture of compliance and intervention.” Silalahi was operating with cultural agility as he leveraged knowledge of the Indonesian culture—appealing to the group orientation to influence behavior—and underscored the importance of Shell’s safety practices.

Cultural Minimization: Cultural Messages to Influence Standardization

Successfully maintaining standards takes more than speeches; it requires culturally agile professionals who can be influential across cultures. It’s challenging enough to influence colleagues, subordinates, supply chain partners, vendors, and the like in one’s own culture, but influencing them in a cross-cultural or multicultural context is fraught with potential misunderstandings, conflict, and feelings of being manipulated. Appropriate influence methods are, in part, culture bound and can be leveraged to achieve successful acceptance of practices and policies that need to be implemented.

Ping Ping Fu and fourteen of her colleagues from around the world conducted an extensive study on cross-national differences in the effectiveness of influence strategies.14 They found that individuals’ social beliefs affect how various influence tactics are perceived. For example, those who believe that life’s events are predetermined by fate and destiny perceived being assertive and coercive (as opposed to, say, building a positive social relationship) as an effective influence strategy. In collectivist or group-oriented cultures, building a positive social relationship (as opposed to, say, being assertive and coercive) was considered the more effective influence strategy.

Theo van der Smeede, a culturally agile Dutch professional, knows that being influential is critical to maintaining consistency around the world. When Theo was working as a quality and safety manager and adviser for Exxon Mobil, he was responsible for developing, assessing, and helping implement standard safety management practices and common processes around the world. He worked regularly in refineries, chemical plants, and laboratory sites in Europe, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, and Chile. Reflecting on the cross-cultural challenges in standardizing practices, he noted that the greatest difficulty in maintaining consistency and standards across cultures was “trying to understand and adjust my approach to influence others from different cultures according to the situation, rather than pursuing my own headstrong approach.” Theo stresses that “even with the most straightforward practices, it is wrong to assume that cultural differences don’t exist. They do—differing by country, organization, and team.” Theo acknowledges that some ways to influence behaviors are shared universally, such as “the need to create ownership for new initiatives rather than pushing these down people’s throats.” Other methods, he quickly added, are more culturally dependent.

Theo’s cultural agility is best seen when he describes the many concurrent factors—organizational, individual, and cultural—that he needs to consider before successfully implementing any standard practice. Theo has seen differences between industries—for example, between oil refineries and chemical manufacturing plants. The refineries themselves are more similar, and those working in them tend to be more willing to adopt common practices, whereas chemical plants are highly diverse, and the professionals who work in them are apt to question a new safety practice. He also notes the differences among individuals and how those differences can affect the implementation. Some people are more interested in adapting the practices put forth, tailoring them a bit for use within their respective units; others are more interested in innovating or being the ones to develop the practice they will eventually follow.

Although he is sensitive to these individual and organizational differences, Theo has also observed many cultural differences affecting the implementation of safety management practices. With an example of how to introduce a new standard safety practice globally, Theo illustrates how he has navigated around the differences. He describes colleagues from his own culture, the Dutch, as being direct, logical, and questioning; they will vigorously debate the points of the new safety practice. With them, he allows the debate to ensue because, ultimately, once they are satisfied with the reasons offered in debate, “they are very committed” to its full implementation. Theo notes that his Belgian colleagues, though more reserved than the Dutch, will also debate prior to buying into the new practice. With them, however, he needs to invite greater debate at the onset, an invitation not needed when working with his Dutch colleagues. Among his British colleagues, the debate cannot be disregarded even though (to his Dutch ear) it sounds less direct, more polite, and more focused on ways to improve the safety practice. His American and German colleagues will buy into the practices they have engineered themselves. Theo has found that bringing them in from the beginning, rather than convincing them of the need for the practice after the fact, allows for greater buy-in. Theo’s Saudi, French, and Italian colleagues will debate and discuss the practice, the alternatives, and possible improvements, but will more readily acquiesce to a “this is how it will be” directive from the appropriate leaders within the hierarchy.

With all of these moving parts, Theo revisits an approach, honed over many years in collaboration with safety management colleagues and under the advice of a psychology professor in Germany, to influence safety behaviors across cultures. At the core of this approach, Theo knows that he needs to understand individual, organizational, and cultural differences in several areas, including

- Beliefs or attitudes toward the new practice

- Willingness to change behaviors

- Routines, norms, or habits affecting the desired behaviors

- The consequences of behaving—or not behaving—in a certain way

To the latter point, in particular, he encourages those who are trying to create a common standard to identify positive and negative consequences most appropriate for influencing behaviors in any given cultural context.

As Theo’s case illustrates, influencing others to act in a manner that is possibly outside their cultural norm requires culturally agile professionals to thread the proverbial needle—to accurately read and understand the cultural elements embedded in the situation and, at the same time, use the most appropriate influence strategy to change behavior so as to override or minimize those differences. Because cultural minimization requires such advanced skills, I strongly encourage organizations to select their most culturally agile professionals, like Theo, to staff positions that require significant cultural minimization.

Cultural Integration

The previous two sections have presented either end of a continuum. At one end, professionals are placed in situations where their decisions and behaviors (for example, sales and operations management) might require adaptation to the other culture’s way of doing things. In these cases, the other culture controls the situation either because of the power differential in the relationship (for example, the buyer, the regulatory body or government) or because forcing others to adapt their behaviors to the professional’s culture does not make sense. Asking production workers to change behaviors just for the sake of changing behaviors (and not for a strategic need) is often a wasted effort that can backfire. At the other end of the continuum, some professionals’ decisions and behaviors (for example, those related to safety and quality) might require that their cultural norms (or their company’s norms) be maintained even when they are contrary to those of the host culture. In these cases, the professional is charged with the role of upholding a standard because it is in the best interest of the company (for example, quality standards, accounting rules, codes of ethics) or in the best interest of the colleagues with whom the professional is working (for example, maintaining strict health and safety practices). At both ends of this continuum, the contextual demand of the role, activity, or job is determining the best way to manage the differences in cross-cultural behaviors and norms.

In many professional situations, however, the best approach will not be at either end of the continuum; instead an integrated (or compromised) approach, not fully reflecting either (or any) of the cultures involved, is the most effective. In these cases, global professionals need to understand when—and how—to create an approach that works across cultures. The most common of these situations is the geographically distributed team—that is, one comprising members who belong to different cultures and are located in multiple countries.

Global professionals need to understand when—and how—to create an approach that works across cultures.

Cultural Integration: Creating a Hybrid Team Culture

In a series of studies to better understand cross-cultural team functioning, P. Christopher Earley and Elaine Mosakowski found that heterogeneous (that is, diverse) teams functioned better, over time, when they had created a hybrid team culture—their own norms for interactions, communications, goal setting, and the like.15 These researchers advise that teams work on the “establishment of rules for interpersonal and task-related interactions, creation of high team performance expectations, effective communication and conflict management styles, and the development of a common identity.”

Jason Newman, an American culturally agile bioscience researcher who has worked as a global project leader in Germany for CSL Limited (a biopharmaceutical company headquartered in Melbourne, Australia), could provide many examples of the validity of these research findings. Through his experience in leading teams of scientists from diverse cultures, Jason understands firsthand the importance of team-level cultural integration to achieve the team’s goals, noting that “team leaders need to recognize the culture lenses of the members and remove the hurdles for a team’s unique culture to emerge.”

Recognizing cultural differences and becoming culturally agile started in an unlikely way for Jason. He was born and raised in a culturally diverse suburb of New York City. He fondly recalls traveling to Quebec City, Canada, as the first spark to kindle his interest in a global career. He learned something about himself during that trip: that he sensed and deeply appreciated cultural differences, including those related to language, food, and interactions. Jason’s cultural interests reemerged a few years later when he was in college, working as a lab technician with scientists from a number of countries. Jason recalls many interesting conversations with colleagues and classmates from Asia, talking about cultural differences while sharing their common interests and academic pursuits in biochemistry and molecular biology in the Microbial Pathogen Department. Later in his professional career, Jason was able to draw on many of the lessons learned during those conversations, recalling that “in college, I learned not to assume similarities; even though we all spoke the same scientific language, the messages were internalized and acted upon in different ways. In retrospect, I was learning to collaborate outside of my own cultural norms.”

In 2004, Jason began to hone his global team skills in international roles. Working in a technical sales role for JRH Biosciences, a subsidiary of CSL, Jason now had responsibilities spanning the globe—in the United States, Europe, and Asia. His cross-cultural competencies were used daily and began to grow exponentially. Jason’s successful sales campaigns required careful consideration of regional business norms, of differences among his internal and external staff members, and of the importance of cultural differences in developing interpersonal relationships and team cohesion. Jason underscored that “when unaware, even seemingly minor faux pas could have negative consequences on client relations and team success.”

CSL noticed Jason’s cross-cultural competencies. In 2007, he accepted a position with CSL as a global project leader in the project management department based in Marburg, Germany. In this role, he managed a global development project team with R&D activities in the United States, Europe, and Australia. The diverse cultural backgrounds of his team provided a fascinating work environment—and also some challenges for team leadership. His R&D teams differed in their risk tolerance: some were more conservative, whereas others took greater risks. The teams also differed in their methodological focus—the same tasks that a given team found essential, another team brushed off as trivial.

Jason knew that when he accepted the team leadership role, he also accepted the challenge of building collaborative trust and respect and establishing a team process that would work for everyone, irrespective of culture. He shared that “the lack of personal relationships was undermining the team, and the cultural differences, had they remained unchecked, would have had a powerful negative influence on our team’s success.” Jason’s first course of action was to develop a foundation of cross-cultural understanding.

Recalling the powerful lessons he learned from conversations he had had in college, and calling on the successful methods employed in his professional experience, Jason started with relationship building as the most direct route toward increasing the team members’ cultural understanding. He carefully selected team members from each development site to work collaboratively, offering them coaching opportunities for awareness building and reinforcing mutual respect and cohesion. Over time, Jason and his team created a hybrid and high-functioning team culture among his global team members, who were also culturally agile. Jason commented, “When I started working in my current role, I was concerned with the cultural differences and focused immediately on the collaboration aspect to bring together the people, processes, and methodologies. My past experiences had highlighted that without a functional understanding of cultural differences, significant effort is required to build trust and collaboration as a result of cultural misunderstandings. When I see collaboration across sites and cultures and the application of best practices, I am proud of the time spent establishing links and building relationships that will continue to pay dividends.” As Jason’s example illustrates, the creation of a global team’s hybrid culture is critical for a team’s success.

Cultural Integration: Does “No Blame” Mean “No Accountability”?

Let’s consider another example of a hybrid team culture. In preparation for the 2000 Summer Olympics, held in Sydney, Australia, a priority was set to clean up Sydney Harbour—a massive undertaking that would involve a global budget, TV coverage, and a twenty-kilometer tunnel under an affluent neighborhood north of the harbor.16 Consultants were brought in to work with this extensive alliance of professionals to help create their project team culture. They ultimately helped the team compile a list of value statements, which included two core values—striving to produce solutions that were “best for project” and creating a “no-blame” culture—along with a list of ten principles to guide behavior:17

Although obviously the project was located in Sydney, the guiding principles did not fit any culture completely. For example, one of the Australian project leaders in this alliance expressed concern that the “no-blame” aspect of the team culture was countercultural for the Australians. Describing the example of a colleague being late for a meeting, he noted how difficult it was when “you couldn’t call anybody up on what they hadn’t done. That it meant no one could go up to someone and say ‘tighten your schedule, you said you would be here at two o’clock. I’ve structured my day around you being here at 2 pm and you arrived at 3 pm. I’m losing confidence that you are going to do what you say you’re going to do!’ . . . I think that [no-blame culture] is something Australians find really difficult to deal with. In Australia it’s more like ‘Hey, you get lost or something?’”18 In his view, “no blame” would translate to a lack of accountability.

In spite of the principles’ not being fully culturally comfortable for every team member, these professionals adhered to their integrated team culture and worked together exceptionally well. Not only was Sydney Harbour cleaned on time for the Olympics, but all the stakeholders were abundantly satisfied—including three eighty-ton whales who returned to the (now cleaner) waters of the harbor.19

Cultural Integration in Mergers and Acquisitions

As with work on cross-cultural teams, other professional situations require an integrated approach to cross-cultural differences. Integrating cultures is also critical when two companies come together through a merger or acquisition. In this context, one of the best examples is Lenovo’s acquisition of IBM’s PC division. Prior to the acquisition, certain ground rules were set by Lenovo’s chairman and CEO, Yang Yuanqing and Steve Ward.20 These ground rules were characterized as three guiding principles of cooperation for the entire company to follow:

- Candor

- Respect

- Compromise

Yang and Ward also did one more thing: they chose their cultural “battles” carefully. In other words, the Lenovo leaders did not try to impose a consistent approach unless one was needed. Nor did they try to culturally integrate practices if they anticipated that doing so would be overly time consuming and not practically or strategically necessary. In a keynote address to the Academy of International Business, Liu Chuan Zhi, CEO and president of Legend Holdings Ltd. (the parent company that acquired Lenovo), described a salient example of this type of cultural agility and the foundation on which Yang and Ward built their approach to the acquisition. In speaking about cultural compromises between Lenovo and IBM, Liu sagely offered this approach:

In order to promote common interests, we divided issues into significant and inconsequential ones. For the latter, we felt that there was no point in wasting time and energy on them, so that we could focus our attention on the significant issues that need to be addressed. We realized that, if we did not compromise, there would be conflicts where no progress could be made. And it might even lead to destructive factions of two different nationalities within the company. We have yet more work to do in the area of cultural integration. I am happy to say, though, that thus far we are progressing satisfactorily along this front.21

It is a reflection on Liu’s culturally agile leadership that he was selected as the recipient of the 2006 Distinguished Executive of the Year Award by the Academy of International Business Fellows.

TAKE ACTION

Based on the information presented in Chapter Two, the following is a list of specific actions you can take to begin implementing the first three competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework within the context of your organization:

- Review the competency models currently being used in your organization (for example, the leadership competency model). Are any of the competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework already embedded into competency models that your organization uses? Can you align them to make sense with your existing framework? Which of the competencies are missing from the existing framework? Can some or all of the missing competencies be added?

- Think about the ten most critical positions in your organization. When considering each of these positions in a global context, is there a behavioral response (cultural adaptation, cultural minimization, or cultural integration) that would be most critical for success in the given role (for example, cultural minimization for quality control managers)?

- In considering those critical global roles, is there agreement on the best possible behavioral response—or is the full repertoire of all three behavioral responses needed?

Notes

1. Patrick J. Kiger, “Corporate Crunch,” Workforce Management, April 2005, 32–38.

2. Ben & Jerry’s, “Scrapbook,” http://www.benjerry.com/company/history/; “Ben & Jerry,” Biography, DVD (New York: A&E Home Video, 2008).

3. For more on Ben and Jerry’s continued corporate social responsibility, see http://www.unileverusa.com/brands/foodbrands/benandjerrys/.

4. Kiger, “Corporate Crunch.”

5. The Economist Intelligence Unit, The Global Talent Index Report: The Outlook to 2015 (Chicago: Heidrick & Struggles, 2011), 14.

6. Chantihika Pornpitakpan, “The Effects of Cultural Adaptation on Business Relationships: Americans Selling to Japanese and Thais,” Journal of International Business Studies 30, no. 2 (1999), 317–337.

7. “Rankings,” Darla Moore School of Business, http://mooreschool.sc.edu/about/rankings.aspx; see also U.S. News & World Report, “International: Best Business Schools,” 2011, http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-business-schools/international-business-rankings.

8. Giles Hirst and others, “Cross-Cultural Variations in Climate for Autonomy, Stress and Organizational Productivity Relationships: A Comparison of Chinese and UK Manufacturing Organizations,” Journal of International Business Studies 39, no. 8 (2008): 1343–1358.

9. My analysis was based on data from the following study: Paula M. Caligiuri and Ibraiz Tarique, Dynamic Competencies and Performance in Global Leaders: Role of Personality and Developmental Experiences (Alexandria, Virginia: SHRM Foundation, 2011), http://www.shrm.org/about/foundation/research/Pages/SHRMFoundationResearchCaligiuri.aspx.

10. Shung J. Shin, Frederick P. Morgeson, and Michael A. Campion, “What You Do Depends on Where You Are: Understanding How Domestic and Expatriate Work Requirements Depend Upon Cultural Context,” Journal of International Business Studies 38, no. 1 (January 2007): 64–83.

11. Andrew Spicer, Thomas Dunfee, and Wendy Bailey, “Does National Context Matter in Ethical Decision Making? An Empirical Test of Integrative Social Contracts Theory,” Academy of Management Journal 47, no. 4 (2004): 610–620.

12. Maddy Janssens, Jeanne Brett, and Frank Smith, “Confirmatory Cross-Cultural Research Testing the Viability of a Corporation-Wide Safety Policy,” Academy of Management Journal 38, no. 2 (1995): 364–382.

13. T. Hidayat, “Darwin Silalahi: Aiming to Become a Memorable Leader,” Jakarta Post, August 22, 2007, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2007/08/22/darwin-silalahi-aiming-become-memorable-leader.html

14. Ping Ping Fu and others, “The Impact of Societal Cultural Values and Individual Social Beliefs on the Perceived Effectiveness of Managerial Influence Strategies: A Meso Approach,” Journal of International Business Studies 35 (2004): 284–305.

15. P. Christopher Earley and Elaine Mosakowski, “Creating Hybrid Team Cultures: An Empirical Test of Transnational Team Functioning,” Academy of Management Journal 43, no. 1 (2000): 26–49.

16. Tyrone S. Pitsis and others, “Constructing the Olympic Dream: A Future Perfect Strategy of Project Management,” Organization Science 14, no. 5 (2003): 574–590.

17. Ibid., 577.

18. Ibid., 585–586.

19. Pitsis and others, “Constructing the Olympic Dream.”

20. Chuan Zhi Liu, “Lenovo: An Example of Globalization of Chinese Enterprises,” Journal of International Business Studies 38 (2007): 573–577.

21. Ibid., 576.