CHAPTER 3

NINE CROSS-CULTURAL COMPETENCIES AFFECTING SUCCESS OF CULTURALLY AGILE PROFESSIONALS

As you’ve just seen in Chapter Two, the first three cross-cultural competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework (cultural minimization, cultural adaptation, and cultural integration) are distinct because they enhance success only when they are activated at the right time and in the right way. The remaining nine competencies operate in a more intuitive, “more is better” fashion. They enable professionals to be effective in intercultural situations by helping them manage their own response set so as to quickly, comfortably, and effectively work in different cultures and with people from different cultures. These competencies also facilitate culturally agile professionals’ abilities to connect with others from different cultures, communicate appropriately, effectively build trust, and gain credibility. These competencies also enable professionals to make appropriate decisions by accurately reading the cultural context—the interconnected system of the countries or cultures in which they are operating—and responding appropriately to it while accounting for the business strategy at hand. Let’s delve deeper into these nine remaining competencies.

THREE COMPETENCIES AFFECTING PSYCHOLOGICAL EASE IN CROSS-CULTURAL SITUATIONS

The next time you are in an international airport, spend a few minutes observing people who are entering the country as visitors. For example, if you watch foreigners asking directions to the taxi stand or baggage claim, you can see that some are tense and anxious, and others are at ease. This same tension-ease contrast can be observed among professionals working in cross-cultural contexts long after they’ve left the airport. Some will feel confident and relaxed from the start. Some will feel like fish out of water at first, but adjust to the host country and feel more comfortable over time. Others will not really feel comfortable again until the moment they return home. All three responses are possible, but only the first two are acceptable for culturally agile professionals.

The Italian executive Rachele Focardi-Ferri remembers being overwhelmed by this fish-out-of-water feeling the day she landed in Mumbai, India, in 2007. Universum Communications, a Swedish-headquartered consulting company specializing in employer branding, had appointed her as its country manager for India, despite the fact that she had never been there. As Rachele recalls, “alone and exhausted . . . I looked around the airport and asked myself how a young woman from Italy would really be able to successfully communicate and do business with the Indian heads of the world’s leading organizations.”

Rachele’s pause at the airport was perfectly understandable. Not only was her mind having a moment of self-doubt; her body was also responding to the experience with feelings of nervous anticipation. Research has found that compared to professionals working in their home countries, many professionals working in foreign countries experience physiological changes in their stress hormones, including increases in prolactin level and decreases in testosterone level.1 These physiological responses can last for several years in the foreign environment. Global professionals who are equipped with the cross-cultural competencies and individual characteristics that help reduce the psychological discomfort of living in the cross-cultural context tend to do better physiologically as well as psychologically.

Research has found that compared to professionals working in their home countries, many professionals working in foreign countries experience physiological changes in their stress hormones.

The good news is that Rachele packed her cultural agility along with her suitcase. Culturally agile professionals have the cross-cultural competencies necessary to combat their bodies’ and minds’ reactions to the stress of the cross-cultural context. The ways that Rachele adjusted to living and working in India illustrate these important competencies. First, she had a high tolerance of ambiguity, indicated by the fact that she had accepted the role in a country she had never before visited and felt comfortable in the cross-cultural context without the structure of her familiar corporate environment. Second, she had an appropriate level of self-efficacy: the humility to realize that she had a lot to learn about India and, at the same time, confidence in her ability to learn to be successful there. Third, she also had a natural curiosity about people and cultures and was sincere in her interest to learn about both. Rachele describes how she approached the new experience in India:

I put on my young traveler’s hat—the one I used when I traveled the world as a student with a backpack—and experienced India like a local. I gave up the car service and showed up to meetings on a rickshaw, ate local food at local restaurants, developed friendships with Indian colleagues, and showed a sincere interest and excitement toward the Indian culture—the religion, traditions and all that India had to offer. I asked questions, lots of questions, and learned all I could. The people I met appreciated my enthusiasm and even gave me an Indian nickname, “Rakhi,” which is the name of a special bracelet that sisters and brothers in India give to each other to symbolize their bond. To this day, this is still the name many of my Indian clients call me.

Rachele was very successful in India, describing her two years managing the business there as one of the best personal and professional “stretch” experiences of her life. Having honed an even higher level of cultural agility, she now lives and works in Singapore, overseeing Universum’s entire Asia-Pacific business.

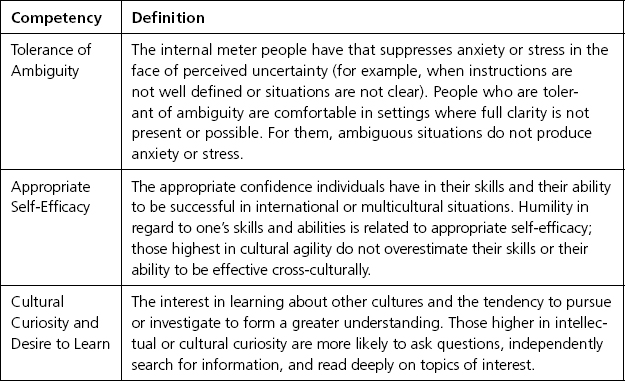

For the past twenty years, I as well as many others have been conducting research on the competencies that predict success among international assignees, like Rachele, who are living and working outside their home countries, and global business professionals who are working on international activities. Starting with the competencies affecting individuals’ psychological ease cross-culturally, as defined in Figure 3.1, we can examine the validity evidence—the proof that certain cross-cultural competencies are present in more effective culturally agile professionals.

FIGURE 3.1. Cross-Cultural Competencies Affecting Psychological Ease

Tolerance of Ambiguity

Cross-cultural situations are often filled with ambiguities that can potentially be anxiety producing for some individuals. These ambiguities can be major (for example, not being able to accurately interpret behaviors during a high-stakes business negotiation) or minor (for example, being unsure why colleagues from a given culture do not speak up during staff meetings). When a situation is difficult to interpret, the outcome cannot be predicted, producing anxiety for many. People with a higher tolerance for ambiguity, like Rachele, are able to accept the fact that cross-cultural situations often hold some “unknowns.” They can remain relaxed and patient until, over time, they understand more about the country, the culture, and the context.

In a study of global business professionals, Ibraiz Tarique and I looked at the relationship between cross-cultural competencies and supervisors’ ratings of global business professionals’ success on a variety of activities with global scope (for example, managing subordinates from different cultures, managing a budget globally).2 We found that business professionals who have a greater tolerance of ambiguity are rated by their supervisors as more effective in their global professional tasks. The same result was found in predicting performance among international assignees living and working internationally.3

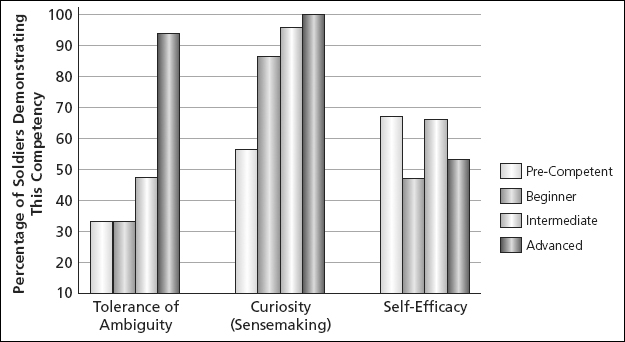

The same result also was found for soldiers who were stationed internationally. Working in conjunction with the U.S. Army Research Institute, researchers Michael McCloskey, Kyle Behymer, Elizabeth Lerner Papautsky, Karol Ross, and Allison Abbe conducted a study to better understand the cross-cultural competencies that differentiate soldiers at a higher level of cross-cultural effectiveness from those at a lower level.4 Their study identified four levels of cross-cultural effectiveness—pre-competent, beginner, intermediate, and advanced—and evaluated soldiers’ responses to assess their cross-cultural competencies. With respect to the characteristics affecting individuals’ psychological ease, tolerance of ambiguity and curiosity (or sensemaking, as it was called in their study) are higher among the soldiers at an advanced level of cross-cultural competence. These results are shown graphically in Figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.2. Soldiers’ Competencies Affecting Psychological Ease Cross-Culturally

Source: Data from Michael McCloskey, Kyle Behymer, Elizabeth Lerner Papautsky, Karol Ross, and Allison Abbe, A Developmental Model of Cross-Cultural Competence at the Tactical Level, Technical Report 1278 (Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2010).

Culturally agile professionals can effectively and comfortably work in different cultures and with people from different cultures. If we underscore “comfortably” for a moment, then the need for tolerance of ambiguity among your pipeline of global professionals becomes even more critical. In a meta-analytic study (combining the results of multiple studies), Michael Frone found that those with a higher tolerance of ambiguity are less vulnerable to the negative effects of job-related stress and strain caused by roles with less clarity and more ambiguity.5 Professionals with a higher tolerance of ambiguity feel more comfortable in uncertain or stressful environments, and are less likely to use negative stereotypes6—another useful attribute among culturally agile professionals. You can get a sense of Rachele’s high tolerance for ambiguity when she describes why she believes other foreign professionals struggle to be effective in India: “Too many foreign business professionals become very nervous in India when things do not run as smoothly as they do in their home countries. You need to take time to better understand the complexity of how to get things done. It is very different . . . I saw too many foreigners in India openly show their aversion toward the noise, the pollution, the food, and the people. They seemed to be lashing out because of their own insecurities.”

Culturally agile professionals can effectively and comfortably work in different cultures and with people from different cultures.

Appropriate Self-Efficacy

Psychologist Albert Bandura coined self-efficacy as the term for one’s belief in one’s ability to succeed in a given situation. As a cross-cultural competence, self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to perform one’s role in a cross-cultural context. Did you notice that of the twelve competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework, self-efficacy is the only one qualified by the word “appropriate”? There is good reason for this. You might recall the study I conducted, described in Chapter One, in which new International MBA graduates assumed that they would be successful working internationally on the global rotation of their employers’ global leadership development program. Their self-efficacy was high before they actually worked internationally. The study found that those who were currently on the international rotation of the global leadership development program, or had already been on it, had lower self-efficacy in regard to their abilities to be effective internationally. This group had worked abroad and better understood the importance of the cross-national context. Self-efficacy was more appropriate among those who understood the context of working internationally.

Professionals who have a high level of confidence in their ability to succeed in a cross-cultural context, but who don’t fully understand the powerful influence of the context, generally experience a reappraisal of their self-efficacy and a healthy new appreciation for the effects of the cultural context after they attempt to work in that context. I would have been very concerned for Rachele if she had stepped off the plane in Mumbai believing she had all she needed to be successful. Her initial hesitation and anxiety were important in her adjustment to an appropriate level of self-efficacy. As illustrated earlier in Figure 3.2, appropriate self-efficacy was replicated in a military sample as soldiers gained competence. As with the previous study, those with greater cross-cultural competence had lower self-efficacy than those with less cross-cultural competence.

Taken together, these studies offer a clear picture: the more individuals learn about what it takes to be effective in cross-cultural environments, the better they understand the magnitude of the challenges and the more accurately they can appraise their skills and abilities for working in such environments. As professionals become more culturally agile, they learn a more appropriate level of self-efficacy and have greater humility in regard to the skills and abilities they need to be effective internationally. Being aware of how little you know is, in fact, very good when working cross-culturally.

Once professionals gain an appropriate level of self-efficacy, this attribute can help them be successful and further develop their cultural agility. For one thing, self-efficacy is related to professional success.7 Believing one can succeed produces motivated behavior needed for success. Second, professionals with higher self-efficacy have more contact with colleagues from different cultures and are more willing to seek out new experiences—both of which can increase effectiveness in cross-cultural contexts and further increase cultural agility.8 Third, self-efficacy is related to international assignees’ work-related cross-cultural adjustment.9

Cultural Curiosity and Desire to Learn

Rachele Focardi-Ferri described how, when she was in India, she asked questions, lots of questions. Her natural curiosity is an attribute she shares with other culturally agile professionals, those who would also describe themselves as having a relentless desire to learn about cultures and make sense of their new cross-cultural context. Culturally agile professionals are more likely to ask questions about norms, customs, values, behaviors, and other aspects of culture that are unfamiliar. They are more likely to actively search for knowledge about the history, religion, legal system, and other aspects of the cultures of the countries they will visit and the people with whom they will work.

As we can see from the military study illustrated in Figure 3.2, cross-culturally competent soldiers were more likely to engage in these knowledge-seeking or sensemaking behaviors. Curiosity is the grease of the cultural understanding machine, enabling professionals to learn through the contact they have with the people and circumstances of their cross-cultural environment.10 Combining curiosity with actual opportunities to interact with peers from different cultures—who can, in fact, accurately answer those curious questions and help professionals make sense of the context—will further accelerate the development of cultural agility.

Curiosity is the grease of the cultural understanding machine.

THREE COMPETENCIES AFFECTING CROSS-CULTURAL INTERACTIONS

Have you ever tried a new restaurant and asked the waiter for a meal suggestion? Have you ever been lost while driving and stopped to ask for directions? Have you ever needed to hire a contractor or physician and asked someone you trust for a recommendation? My guess is that you have had each of these experiences at some point in your life. Most of us have. The way we as humans make sense of unfamiliar situations is often through the relationships we forge with others who can guide us. Effective interactions with people from different cultures are not just the goal of culturally agile professionals; they are the way in which professionals become culturally agile. They are the process, not the outcome. Culturally agile professionals seek to reduce ambiguity and learn to navigate diverse cross-cultural contexts. This is most often achieved through their contact with others, their willingness to develop relationships with people from diverse cultures, and their ability to see things through the lens of those with a different set of values.

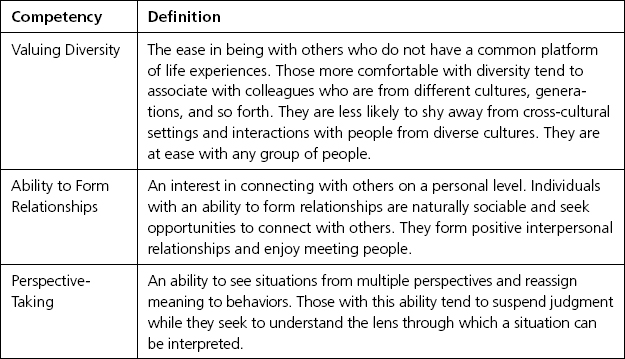

In this section, we will examine the three competencies from the Cultural Agility Competency Framework that affect individuals’ propensity to engage in these kinds of multicultural interactions. They are listed in Figure 3.3.

FIGURE 3.3. Competencies Affecting Individuals’ Cross-Cultural Interactions

Sean Dubberke, a culturally agile professional, has spent the better part of his career helping professionals learn to navigate the cross-cultural contexts in which they are placed. As director of intercultural programs at RW3 CultureWizard, Sean trains corporate professionals on how to develop their relationships and be effective working across cultures. Sean, who is American, also practices what he preaches. Speaking five languages (English, Spanish, German, French, and Japanese) and having lived in Spain, Germany, and the United Kingdom, Sean is aware of how his own cultural agility has grown through the personal and professional relationships he has developed over the years.

The realization that relationships were critical for cultural understanding began early for Sean. When he spent a college year abroad in Spain, he chose to be immersed in the Spanish culture by sharing an apartment with Spaniards rather than living with American students. In addition to his educational pursuit, Sean’s goals for living and studying in Spain were to become a part of the fabric of the local community, to improve his Spanish language skills (including colloquialisms), and to understand the nuances of Spanish culture. To help Sean find a flat and roommates in a way Madrileños do, a friend directed him to Segunda Mano, a collection of classified ads published only in Spanish. This proved a successful strategy. Sean found a room in a flat with three Spaniards, roommates who later became his close friends. Valuing cross-cultural experiences over the psychological ease of living with fellow Americans, Sean started building his cultural agility.

Although Sean had always been an extrovert, his cultural agility began to snowball after his experience in Spain; his natural curiosity and sociability continue to propel him to seek and form deep relationships with friends and colleagues from diverse cultures and, in turn, to learn about cultures with each cross-cultural experience. A few years after living in Spain, Sean embraced an opportunity to live and work in Leipzig, Germany. Sean credits his success in Germany to his German friends and colleagues, describing how they “helped me learn the German language and guided me as I learned about the culture. They helped me understand the regional mentality toward business and progress—connecting how this was still linked to a rule-oriented, authoritarian past. It would have been difficult to navigate these regional nuances without their guidance.”

As a natural extrovert, Sean has an aptitude for using social connectedness in a cross-cultural context to build and practice his cultural agility. In an extensive study examining the successful predictors of globally mobile professionals in many countries, researchers Margaret Shaffer, David Harrison, Hal Gregersen, J. Stewart Black, and Lori Ferzandi found that, among other traits, those who were more extroverted and people oriented were more successful and better adjusted to working internationally.11

The results that Margaret and her colleagues found in their research studies were replicated among global professionals; Ibraiz Tarique and I found that global professionals were more successful when they had the natural tendency toward forming relationships and were given the opportunity to do just that.12 Our study found that global professionals, like Sean, who both are extroverted and had high-contact experiences with culturally diverse peers were most successful in their subsequent cross-cultural professional activities.

In the study of soldiers described in the previous section, Michael McCloskey and his colleagues found that soldiers’ ability to form relationships differentiates soldiers at a higher level of cross-cultural effectiveness from those at a lower level.13 As you can see in Figure 3.4, ability to form relationships (assessed as both relationship building and rapport building), and perspective-taking were higher among the soldiers at an advanced level of cross-cultural competence.

FIGURE 3.4. Soldiers’ Competencies Affecting Cross-Cultural Interactions

Source: Data from Michael McCloskey, Kyle Behymer, Elizabeth Lerner Papautsky, Karol Ross, and Allison Abbe, A Developmental Model of Cross-Cultural Competence at the Tactical Level, Technical Report 1278 (Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2010).

Valuing Diversity

Years before his stay in Madrid as a college student, Sean Dubberke had already been seeking out cross-cultural experiences. He described a time when he was thirteen and petitioned his parents, unsuccessfully, to take him to Japan after experiencing Little Tokyo in downtown Los Angeles. Barely a teenager, and realizing that a trip to Japan wasn’t in his immediate future, Sean did the next best thing: he sought out Japanese experiences. Sean dedicated himself to learning the Japanese language, first through self-initiated study at home (memorizing both the Hiragana and Katakana writing systems), then through evening community college courses as a high school student, and, finally, with advanced courses in college and a month-long immersion trip to Japan. Although, as Sean remarked, “the goal was to get to Japan and experience its culture,” the steps leading there exposed him to people and places in his own backyard that resulted in an education in Japanese values. “Even without being fluent, I spent time watching Japanese programs on television, attempted to read manga that wasn’t translated, and surrounded myself with Japanese and Japanophiles alike. Exposure to a diversity of thought was the most influential part of this personal project, which prepared me for life abroad before I knew where I was headed.”

Valuing diversity is a critical competence for culturally agile professionals because cultural agility develops over time. The more that professionals seek out and engage in culturally diverse experiences with colleagues and peers from different cultures—as Sean continues to do—the more they will build their repertoire of culturally appropriate skills and continuously increase their cultural agility. Culturally agile professionals value opportunities to be around those who view life through a different lens and are guided by a different set of cultural norms. They don’t mind being demographically different from others when they are in other countries or with people from other cultures. On the contrary, they seek and embrace these experiences. Ibraiz Tarique and I found that those global professionals who valued cultural diversity to the point where they sought out opportunities to meet and befriend foreigners—and valued the opportunities to do so—were rated as more effective in their global professional activities.14

Culturally agile professionals value opportunities to be around those who view life through a different lens and are guided by a different set of cultural norms.

Ability to Form Relationships

Culturally agile professionals have an advantage when it comes to building a global network of trusted colleagues and business associates. Jon Shapiro, Julie Ozanne, and Bige Saatcioglu conducted a fascinating study of global professionals, North American buyers in the garment industry who spent years working with colleagues in Asia. The most culturally effective among the professionals in their study were able to accurately scan the environments where they were operating, fully understand the nuances of the host cultures, and respond as needed. These buyers were able to form strong and trusted professional relationships with their Asian counterparts. At this advanced level, the American buyers “personally know their suppliers and business partners’ families, socialize with them regularly, and are genuinely committed to working through problems.”15

This ability to form relationships is also important for those professionals who are living and working internationally. In another study, I found that international assignees from a U.S.-based information technology company with a broader base of host national colleagues and friends were more likely to adjust to living and working in their host countries. As Sean Dubberke’s examples illustrate well, his cross-cultural relationships in Spain and Germany facilitated his success in those countries. Culturally agile professionals’ ability to successfully form and foster relationships is a critical competence for global professional success.

Perspective-Taking

In the aforementioned research study on American buyers working in Asia, Jon Shapiro, Julie Ozanne, and Bige Saatcioglu found that professionals pass through stages of understanding as they become more accurate in interpreting their cross-cultural environments over time. In the earliest stage, which these researchers call the “romantic sojourner” stage, professionals are still interacting with the foreign culture as a tourist, at a rather superficial level. They are still using their own frame of reference to interpret the different cultural norms around them. Needless to say, an inability to accurately read the cues from the environment results in misunderstandings, problems, mistakes, and failure. They found that those who are at a higher and more skilled level are able to interpret the cues reliably and to “frame-switch” accurately across various cultures.

Perspective-Taking and the Golden Rule

Well-meaning professionals, often at the early romantic sojourner phase, often ask me this question: “Wouldn’t it make sense to simply treat others the way I’d like to be treated—and not really worry about cultural differences?” This “Golden Rule approach” is a fine way to think about professional intercultural interactions, if (and only if) professionals are willing to adapt the way they “do unto others” to follow the cultural norms of what they wish to be “done unto.”

Try taking the Golden Rule quiz (see box) to see whether your behavioral preferences are universally desirable.

Once you have taken this quiz, you will probably be able to guess why the Golden Rule approach is not sufficient without deeper cultural understanding. For example, in some cultures it would be disrespectful to look someone (especially an elder or someone more senior on the organizational chart) in the eye when you speak to him or her. In Brazil, it is good manners to open a gift immediately—and to express delight and appreciation. In most Asian and Middle Eastern cultures, it is considered impolite or disrespectful to open a gift in the presence of the person who gave it. In China, refusing a gift as many as three times before accepting it conveys humility and respect. In some cultures, such as Brazil, interruption is a way to show engagement in the conversation. In Japan, being acknowledged for your accomplishment individually would be embarrassing. It is also common in Japan for professionals to close their eyes while someone is presenting to think about what is being said—an act that is almost always interpreted as sleeping by those who are not Japanese. Giving a presentation to people who have their eyes closed is especially difficult for those from interpersonally oriented cultures.

| 1. I prefer a person with whom I am speaking to look me in the eyes when he or she talks to me. | |

| 2. I would want a friend to accept and open a gift that I give to him or her. | |

| 3. I would not want to be interrupted when I am speaking. | |

| 4. I would want a colleague to actively listen when I am presenting. | |

| 5. I would want to be acknowledged for my professional accomplishments. | |

| 6. I expect my colleagues to respect my time and not be late. | |

| 7. I prefer to be judged at work by my character and knowledge, not by my appearance. | |

| 8. I would want my personal space to be respected. | |

| 9. I would not want to be touched by someone I do not know. | |

| 10. I would want to be honest with a colleague if I thought he or she was wrong about a work-related decision. |

Let’s continue down the list. In many of the Southern European countries, time is very fluid and does not have the same sense of value as in Germany and North America. Lateness is accepted and tolerated. In Italy, you will be treated according to your appearance; if you do not care about your own appearance, why should others respect you or trust your opinions?

There is more. You may already know that personal space varies from country to country. What you may not realize is that the violation of the space when communicating—either by being too close or not close enough—causes great anxiety. In certain cultures, a touch on the hand or arm when speaking is merely a sign of conversational connection and should not be construed as flirtation or aggression. Most people think of saving someone from embarrassment in connection with Japanese or other Asian cultures, but it is also critical in Latin American cultures and some European ones, such as France and Italy. For example, a business associate who does not care to have a meeting with someone might repeatedly postpone setting a date or location for the meeting rather than appear rude by stating flatly that there does not seem to be any reason to meet. Professional debate, especially when someone is being challenged, considered healthy in many northern European countries, would be considered rude in many other face-saving cultures.

As this rather superficial test was meant to illustrate, the Golden Rule approach requires some knowledge of cultural differences and the ability to see things from another person’s perspective—even if it is not a perspective or value you share. Culturally agile professionals are able to engage in perspective-taking and reassigning meaning to behaviors.

Perspective-Taking and Religion

Sean Dubberke recalls a time when perspective-taking was particularly helpful. He was on his way to a business trip in Oman when a customs official asked Sean about his religion as he crossed the border from the United Arab Emirates. Although that would be an irrelevant and illegal question for government agencies to ask in his home country, Sean sensed that the question was not about judgment but rather that the official was simply curious about the foreigner’s religious stance. Having studied Arabic, Sean realized that for many Middle Easterners, it is often hard to understand how someone could not be religious. Sean explains that “atheism and people who don’t claim to belong to any religious group aren’t visible in the Middle East. It appears vulgar, even selfish, to not believe in any higher power, whatever it may be.”

Sean engaged his perspective-taking abilities and responded to the official by saying he “was of an Abrahamic religion.” This response was well received. The customs official welcomed Sean with a smile and commented on his belief “that religions are actually not all that different.” We can wonder if the official’s warm and philosophical response would have been the same if Sean’s reply had not demonstrated perspective-taking.

THREE COMPETENCIES AFFECTING GLOBAL BUSINESS DECISIONS

Zsolt Vincze, a culturally agile Hungarian professional, knows that a higher-level understanding of history, culture, economics, and the like will help global professionals make the best possible decisions. Zsolt works for a Dutch firm, BEST Group, that sells products and advises clients in the removal and cleaning of hazardous substances. In Hungary, Zsolt advises clients on asbestos removal—but in doing so must maintain the industry standards and BEST Group’s practices, influenced heavily by his company’s strict Dutch standards for health and safety. As an Eastern European, Zsolt understands that the similarities in education and job titles belie the ease of instituting appropriate safety practices. He knows that a single approach that does not account for and integrate knowledge of cultural issues, global standards, and country-level realities will almost certainly fail. Success requires cognitive complexity, taking multiple factors into account.

When Zsolt works in Eastern and Western Europe, he needs to be receptive to adopting different ideas and approaches that will result in the same end—compliance with safety standards. Zsolt understands that in addition to the myriad of cultural challenges, more fundamental challenges related to economics and legal regulations affect whether practices will be followed. For example, in Eastern European countries such as Hungary, there is no regulatory requirement for any type of employee safety training prior to an asbestos removal job—only a voluntary labor safety meeting that might last only a few hours. There is no mechanism in place to regulate compliance with the practices at the organizational level. The opposite is the case in Western European countries. In these countries, associates are required to take an asbestos safety course, which can last between two and five days, with a strict examination and certification. Associates monitor compliance within their work teams and follow the practices with conviction. At the organizational level, there are structured sanctions for not complying with the regulations. Zsolt shares that compliance might not be perfect but that once the safety program is in place, there is widespread adoption in Western European countries.

In Eastern Europe, Zsolt needs to use more of a “macro lens” to be effective in implementing this critical safety compliance. In addition to these regulatory differences between Eastern and Western European countries, there are economic differences. Employees who might otherwise complain about the handling of unsafe materials are fearful of losing their jobs. Zsolt is sensitive to these concerns and takes them into account when developing an approach to safety training. Even with the risk of asbestos as a dangerous carcinogen, it would be inappropriate to recommend an employee-led safety initiative, given that there is great deference to the organization’s leaders.

To work around these very practical realities, Zsolt needs to use his skills of divergent thinking and creativity to influence at an even higher level. For example, he describes encouraging Eastern European government leaders to consider safe asbestos removal as a government-led opportunity for a corporate certification and control system (in other words, one that is revenue generating for the governments) but also a long-term health burden if not addressed. Zsolt forms peer networking groups, mixing leaders from Eastern European firms and multinational companies operating in Eastern Europe. The hope is that when best practices from the multinationals are shared, a more advanced industry norm will be created in Eastern Europe.

Orly Levy, Schon Beechler, Sully Taylor, and Nakiye Boyacigiller would describe Zsolt as having a “global mindset.” Their extensive analysis of the human attributes that underlie executives’ global mindsets uncovered two factors.16 First, focusing on the cognitions that make managers successful in global roles, they discovered that managers with a global mindset operate with “cosmopolitanism.” They define this as “a state of mind that is manifested as an orientation toward the outside, the Other, and which seeks to reconcile the global with the local and mediate between the familiar and the foreign” and also as “a willingness to explore and learn from alternative systems of meaning held by others.” Their examination also found that cognitive complexity was critical given managers’ need to understand and integrate broader bases of knowledge and “simultaneously balance the often contradictory demands of global integration with local responsiveness.” Zsolt clearly demonstrates both cosmopolitanism and cognitive complexity.

Ultimately, the greatest test of whether your organization’s global professionals are successful is related to whether they are able to operate with a global mindset and make the best possible professional decisions in a cross-cultural context. In this section, we will focus on the cross-cultural competencies from the Cultural Agility Competency Framework that contribute to success in this area. They are defined and described in Figure 3.5.

FIGURE 3.5. Cross-Cultural Competencies Affecting Decisions

Knowledge and Integration of Cross-National/Cultural Issues

When executives were asked to name the global business capabilities most critical for younger leaders to possess in order to succeed today and in the future, their responses had a clear theme.17 The most needed areas of knowledge included (but were certainly not limited to) global finance, global strategy, global macroeconomics, and global marketing. They also wanted their leaders of the future to have a worldly awareness and sound judgment, intuition, and decision-making skills. The preceding example of Zsolt Vincze illustrates the need for culturally agile professionals to integrate not only cultural differences but also differences in regulatory, economic, legal, and governmental systems. Zsolt knew that influencing the government and regulatory systems would be more likely to lead to compliance than simply providing safety training to employees in isolation. With a deeper knowledge of global, international, and cultural issues, culturally agile professionals like Zsolt are more likely to understand how the countries are different, interconnected, and aligned. They understand the political, historical, religious, economic, and other factors affecting their organizations’ effectiveness. Having a deep understanding of the complexity of these factors enhances professionals’ abilities to make more informed decisions in a cross-cultural context.

Do you remember the study described in the previous section by Jon Shapiro and colleagues about highly effective North American buyers working in Asia in the garment industry? They found that the most culturally effective buyers had developed over time the ability to see behavioral patterns within different cultures relative to their own culture, and to use their gained knowledge accurately and effectively.18 As with buyers in the garment industry, highly effective soldiers operating globally also demonstrate the same cross-cultural competency. Michael McCloskey and his colleagues found that soldiers’ knowledge and integration of global and cultural issues (assessed as both cultural awareness and integration) was higher among those at an advanced level of cross-cultural competence. Figure 3.6 illustrates this.

FIGURE 3.6. Soldiers’ Competencies Affecting Decisions Cross-Culturally

Source: Data from Michael McCloskey, Kyle Behymer, Elizabeth Lerner Papautsky, Karol Ross, and Allison Abbe, A Developmental Model of Cross-Cultural Competence at the Tactical Level, Technical Report 1278 (Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2010).

Receptivity to Adopting Diverse Ideas

Some of the most stunning, costly, and embarrassing mistakes in international business have been made because business leaders preferred solutions they knew from their home country over solutions that were generated outside their home countries. Consider the case of the world’s largest retailer, Walmart. Although Walmart has achieved impressive successes in several countries, its experience in Germany was a dismal failure. In 2006, Walmart sold its eighty-five stores and pulled out of the country, a move that was estimated to cost about $1 billion. During Walmart’s eight years in Germany, critics cited a host of cultural mistakes.19 Some were highly avoidable. For example, Walmart’s lack of awareness that German bed pillows differ from American ones in size and shape resulted in an unused inventory of thousands of pillowcases that were impossible to sell.

Other mistakes were more complex. The famously nonunion Walmart seriously underestimated the strength of German labor unions and work councils and its need to work with them, not against them, as German law guarantees workers the right to organize. Walmart’s reputation for offering the lowest price was besmirched when German grocery chains undercut Walmart’s food prices. The famous Walmart practice of requiring employees to smile and greet every customer not only was unpopular with employees but also backfired with German customers, who interpreted this behavior as harassment and flirtation.

Being shortsighted about cultural differences in work-life balance preferences ultimately dealt the company the greatest blow in Germany. When Walmart opened its stores, it hired many German executives from the retail chains it acquired, expecting them to relocate. But the U.S.-based firm underestimated the high value Europeans place on remaining rooted in a certain place and connected with extended families. Many German executives quit, leaving Walmart with a dearth of qualified leaders who would have been highly cognizant of these and many other local issues. The Walmart executives’ lack of receptivity to a different way of doing business is clearly apparent in their experience in Germany. Since then, Walmart has made tremendous changes to build its pipeline of culturally agile talent and compete more effectively in different countries around the world.

Culturally agile professionals are able to adapt to new ways of doing things and do not shun ideas merely because they are different. Ibraiz Tarique and I found that those open-minded global professionals who were comfortable and flexible in their willingness to engage in new and different activities were more successful, rated by their supervisors as more effective in their global professional activities.20 This competency of being receptive to exploring and accepting diverse solutions enhances cultural agility because having access to a greater number of plausible options relates to the greater likelihood of success in cross-cultural environments.

Global professionals who were comfortable and flexible in their willingness to engage in new and different activities were more successful.

Divergent Thinking and Creativity

Divergent thinking is the ability to generate multiple solutions or approaches to a given situation, problem, or challenge. You have probably been involved in a brainstorming session at some point in your career. This activity is an example of group-based divergent thinking to generate a wide variety of ideas. Culturally agile professionals are often placed in situations where familiar solutions will not be effective, and alternative, more novel solutions are needed. Zsolt’s bringing together leaders in Eastern European countries with leaders from multinational firms operating in Eastern Europe is an example of his use of divergent thinking to come up with a creative solution. Creative people who think “outside the box” are in high demand in almost every industry and professional field today. This is especially true for those who will be working in cross-cultural environments because the decisions to be made, strategies to be developed, and problems to be solved are often new and untested.

American Peace Corps volunteers who have been working globally to help in the HIV/AIDS crisis have been operating almost daily with this cross-cultural competence. Eric Goosby, the U.S. global AIDS coordinator, credits twenty-five hundred Peace Corps volunteers as partners in the implementation of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the U.S. government’s response to the global AIDS pandemic. In forty-six countries, Peace Corps volunteers are involved in HIV education, including initiatives for HIV prevention, care, and support. Eric notes that Peace Corps volunteers demonstrate their divergent thinking to achieve this goal, stating that “Volunteers’ ‘can do’ attitudes mean that they find ways to ‘make do.’ Where others may see a lack of resources, Peace Corps volunteers see a challenge and they respond with creative solutions . . . I am invariably impressed by the energy, passion and out-of-the-box thinking that volunteers bring to their work in HIV.”21

TAKE ACTION

Based on the information presented in Chapter Three, the following is a list of specific actions you can take to begin implementing these nine competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework within the context of your organization:

- Review the competencies listed in Figures 3.1, 3.3, and 3.5. How do they fit with your organization’s current values or organizational culture? Are they already represented within the organization?

- Identify the critical positions that would most need employees who possess the competencies identified in this chapter—those where success is most critical for the organization’s competitive advantage. As a place to start, integrate these competencies into the performance management systems for these positions.

- Collect critical incidents. Identify about ten situations where individual employees either facilitated or impeded an outcome of strategic importance for your organization (from a cross-cultural perspective). For those employees who were successful, identify the cross-cultural competencies they possessed that contributed to their success. For those who were unsuccessful, identify the cross-cultural competencies they lacked—the ones that, if they had had them, would have increased the likelihood of success.

Notes

1. Ingrid Anderzén and Bengt Arnetz, “Psychophysiological Reactions to International Adjustment,” Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 68, no. 2 (1999): 67–75.

2. Paula M. Caligiuri and Ibraiz Tarique, Dynamic Competencies and Performance in Global Leaders: Role of Personality and Developmental Experiences (Alexandria, VA: SHRM Foundation, 2011), http://www.shrm.org/about/foundation/research/Pages/SHRMFoundationResearchCaligiuri.aspx.

3. Stefan Mol and others, “Predicting Expatriate Performance for Selection Purposes: A Quantitative Review,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 36, no. 5 (2005): 590–620.

4. Michael McCloskey and others, A Developmental Model of Cross-Cultural Competence at the Tactical Level, Technical Report 1278 (Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2010).

5. Michael Frone, “Intolerance of Ambiguity as a Moderator of the Occupational Role Stress-Strain Relationship: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 11, no. 4 (1990): 309–320.

6. Nehemia Friedland, Giora Keinan, and Talia Tytiun, “The Effect of Psychological Stress and Tolerance of Ambiguity on Stereotypic Attributions,” Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 12, no. 4 (1999): 397–410.

7. The relationship between self-efficacy and job performance has been established in a variety of job categories. Among creative professionals, for example, see Pamela Tierney and Steven M. Farmer, “Creative Self-Efficacy: Its Potential Antecedents and Relationship to Creative Performance,” Academy of Management Journal 45, no. 6 (2002): 1137–1148.

8. A number of studies have demonstrated the role of self-efficacy in predicting adjustment in international assignments. See, for example, AAhad M. Osman-Gani and Thomas Rockstuhl, “Cross-Cultural Training, Expatriate Self-Efficacy, and Adjustments to Overseas Assignments: An Empirical Investigation of Managers in Asia,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 33, no. 4 (2009): 277–290. See also Margaret Shaffer, David Harrison, and K. Matthew Gilley, “Dimensions, Determinants, and Differences in the Expatriate Adjustment Process,” Journal of International Business Studies 30, no. 3 (1999): 557–581.

9. Purnima Bhaskar-Shrinivas and others, “Input-Based and Time-Based Models of International Adjustment: Meta-Analytic Evidence and Theoretical Extensions,” Academy of Management Journal 48, no. 2 (2005): 257–281.

10. Curiosity is a term that has a variety of close correlates, such as need for cognition, learning orientation, and intellectual curiosity. For one study linking curiosity with job performance, see Thomas Reio and Jamie Callahan, “Affect, Curiosity and Socialization-Related Learning,” Journal of Business and Psychology 19, no. 1 (2004): 3–23.

11. Margaret Shaffer and others, “You Can Take It with You: Individual Differences and Expatriate Effectiveness,” Journal of Applied Psychology 91, no. 1 (2006): 109–125.

12. Paula M. Caligiuri and Ibraiz Tarique, “Predicting Effectiveness in Global Leadership Activities,” Journal of World Business 44, no. 3 (2009): 336–346.

13. McCloskey and others, A Developmental Model.

14. Caligiuri and Tarique, Dynamic Competencies and Performance in Global Leaders.

15. Jon Shapiro, Julie Ozanne, and Bige Saatcioglu, “An Interpretive Examination of the Development of Cultural Sensitivity in International Business,” Journal of International Business Studies 39, no. 1 (2008): 71–87. (Quotation is from p. 82.)

16. Orly Levy and others, “What We Talk About When We Talk About ‘Global Mindset’: Managerial Cognition in Multinational Corporations,” Journal of International Business Studies 38, no. 2 (2007): 231–258.

17. Nigel Andrews and Laura D’Andrea Tyson. “The Upwardly Global MBA,” Strategy + Business, no. 36 (Fall 2004), http://www.strategy-business.com/media/file/sb36_04306.pdf.

18. Shapiro, Ozanne, and Saatcioglu, “An Interpretive Examination.”

19. Sources of material regarding Walmart in Germany: Andreas Knorr and Andreas Arndt, “Why Did Wal-Mart Fail in Germany?” Materialien des Wissenschaftsschwerpunktes “Globalisierung der Weltwirtschaft,” vol. 24 (Bremen, Germany: Institute for World Economics and International Management, published by Andreas Knorr, Alfons Lemper, Axel Sell, and Karl Wohlmuth, University of Bremen, June 2003), http://www.iwim.uni-bremen.de/publikationen/pdf/w024.pdf; Don B. Bradley III and Bettina Urban, “Wal-Mart’s Learning Curve in the German Market,” Proceedings of the Academy for Studies in International Business 4, no. 1 (New Orleans: Allied Academics International Conference, 2004), http://www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/allied/2004/internationalBusiness/pdf/12.pdf; Louisa Schaefer, “World’s Biggest Retailer Wal-Mart Closes Up Shop in Germany,” Deutsche Welle, July 28, 2006, http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,2144,2112746,00.html; and Mark Landler and Michael Barbaro, “Wal-Mart’s Overseas Push Can Be Lost in Translation—Business—International Herald Tribune,” New York Times, August 2, 2006, http://www.iht.com/articles/2006/08/02/business/walmart.php.

20. Paula M. Caligiuri and Ibraiz Tarique, Dynamic Competencies and Performance in Global Leaders.

21. Eric Goosby, “Peace Corps Volunteers Are Leaders in the Fight Against HIV/AIDS,” DipNote (U.S. Department of State’s official blog), March 31, 2011, http://blogs.state.gov/index.php/site/entry/peace_corps_pepfar.