2

Project management with PRINCE2

This chapter covers:

•projects, project management and project managers

•project variables

•different project contexts

•project management standards

•applying PRINCE2

2 Project management with PRINCE2

A key challenge for organizations in today’s world is to succeed in balancing two parallel, competing imperatives. These are to:

•maintain current business operations (i.e. maintain profitability, service quality, customer relationships, brand loyalty, productivity, market confidence, etc.). This is what we would term ‘business as usual’

•transform business operations in order to survive and compete in the future (i.e. looking forward and deciding how business change can be introduced to best effect for the organization).

As the pace of change (technology, business, social, regulatory, etc.) accelerates, and the penalties of failing to adapt to change become more evident, the focus of management attention is inevitably moving to achieve a balance between business as usual and business change.

Projects are the means by which we introduce change and, although many of the skills required are the same, there are some crucial differences between managing business as usual and managing project work.

Definition: Project

A temporary organization that is created for the purpose of delivering one or more business products according to an agreed business case.

There are a number of characteristics of project work that distinguish it from business as usual:

•Change Projects are the means by which we introduce change.

•Temporary As the definition of a project states, projects are temporary in nature. When the desired change has been implemented, business as usual resumes (in its new form) and the need for the project is removed. Projects should have a defined start and a defined end.

•Cross-functional A project involves a team of people with different skills working together (on a temporary basis) to introduce a change that will impact others outside the team. Projects often cross the normal functional divisions within an organization and sometimes span entirely different organizations. This frequently causes stresses and strains both within organizations and between them (for example, between customers and suppliers). Each has a different perspective and motivation for getting involved in the change.

•Unique Every project is unique. An organization may undertake many similar projects, and establish a familiar, proven pattern of project activity, but each one will be unique in some way: a different team, a different customer, a different location, a different time. All these factors combine to make every project unique.

•Uncertainty The characteristics already listed will introduce threats and opportunities over and above those we typically encounter in the course of business as usual. Projects are more risky.

Projects come in all shapes and sizes. An organization may be undertaking an IT project to deliver improved systems required to manage its business; another organization may be undertaking a clinical research project in order to bring a new drug to market; and a third organization may be managing an event.

Furthermore, the environment within which the project is being managed may influence how it is started up, delivered, assured and closed. There may be factors external to the project itself, such as embedded corporate standards, the maturity of the organization, and regulatory frameworks and factors specific to the individual project such as the industry sector, the geographical location and the project’s risks.

2.2 What is project management?

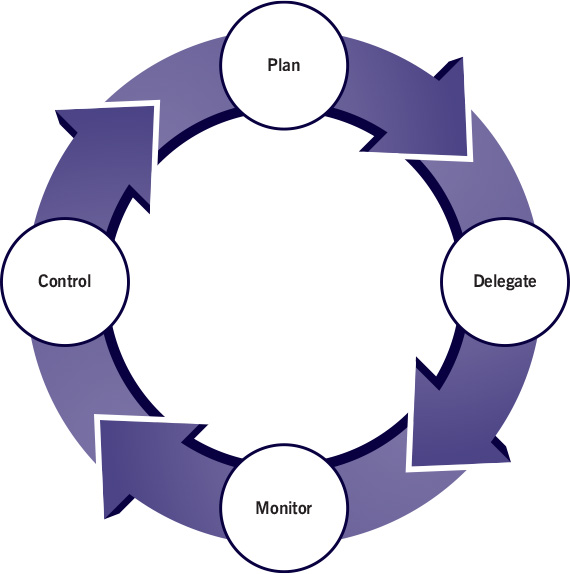

Project management is the planning, delegating, monitoring and control of all aspects of the project, and the motivation of those involved, to achieve the project objectives within the expected performance targets for time, cost, quality, scope, benefits and risk.

For example, a new house is completed by creating drawings, foundations, floors, walls, windows, a roof, plumbing, wiring and connected services. None of this is project management, so why do we need project management at all? The purpose of project management is to keep control over the specialist work required to create the project product or, to continue with the house analogy, to make sure the roofing contractor does not arrive before the walls are built.

Additionally, given that projects are how we introduce a change, and that project work entails a higher degree of risk than many other business activities, it follows that implementing a secure, consistent, well-proven approach to project management is a valuable business investment.

2.3 What is it we wish to control?

There are six variables involved in any project, and therefore six aspects of project performance to be managed. These are:

•Costs The project has to be affordable and, though we may start out with a particular budget in mind, there will be many factors which can lead to overspending and, perhaps, some opportunities to cut costs.

•Timescales Closely linked to costs, and probably one of the questions project managers are most frequently asked, is: When will it be finished?

•Quality Finishing on time and within budget is not much consolation if the result of the project does not work. In PRINCE2 terms, the project product must be fit for purpose.

•Scope Exactly what will the project deliver? Without knowing it, the various parties involved in a project can very often be talking at cross-purposes about this. The customer may assume that, for instance, a fitted kitchen and/or bathroom is included in the price of the house, whereas the supplier views these as ‘extras’. On large-scale projects, scope definition is much more subtle and complex. There must be agreement on the project’s scope and the project manager needs to have a sufficient understanding of what is and what is not within the scope. The project manager should take care not to deliver beyond the scope as this is a common source of delays, overspends and uncontrolled change (‘scope creep’).

•Benefits Perhaps most often overlooked is the question: Why are we doing this? It is not enough to build the house successfully on time, within budget and to quality specifications if, in the end, we cannot sell or rent it at a profit or live in it happily. The project manager has to have a clear understanding of the purpose of the project as an investment and make sure that what the project delivers is consistent with achieving the desired return.

•Risk All projects entail risks but exactly how much risk are we prepared to accept? Should we build the house near the site of a disused mine, which may be prone to subsidence? If we decide to go ahead, is there something we can do about the risk? Maybe insure against it, enhance (underpin) the house foundations or simply monitor with ongoing surveys?

PRINCE2 is an integrated method of principles, themes and processes that addresses the planning, delegation, monitoring and control of all these six aspects of project performance (see Figure 2.1).

2.4 What does a project manager do?

In order to achieve control over anything, there must be a plan. It is the project manager who is responsible for planning the sequence of activities to build the house (e.g. working out when the bricklayers will be required).

It may be possible to build the house yourself, but being a project manager implies that you will delegate some or all of the work to others. The ability to delegate is important in any form of management but particularly so in project management, because of the cross-functionality and risks.

With the delegated work under way, the aim is that it should ‘go according to plan’, but we cannot rely on this always being the case. It is the project manager’s responsibility to monitor how well the work in progress matches the plan.

Of course, if work does not go according to plan, the project manager has to do something about it (i.e. exert control). Even if the work is going well, the project manager may identify an opportunity to speed it up or reduce costs.

Key message

One aim of PRINCE2 is to make the right information available at the right time for the right people to make the right decisions about the project. Those decisions include whether to take corrective action or implement measures to improve performance.

PRINCE2 assumes that there will be a customer who will specify the desired result and (usually) pay for the project, and a supplier who will provide the resources and skills to deliver that result.

PRINCE2 refers to the organization that commissions a project as ‘corporate, programme management or the customer’ (by ‘corporate, programme management’ we mean corporate or programme management). This organization is responsible for providing the project’s mandate, governing the project, and for realizing any benefits that the project might deliver or enable (for projects in programme and portfolio contexts, see sections 2.5.2 and 2.5.3).

PRINCE2 refers to a supplier as the person, group or groups responsible for the supply of the project’s specialist products.

Projects can exist within many contexts; they may be stand-alone (with their own business case and justification) or they may be part of a programme or wider portfolio. Figure 2.2 shows how projects may fit within a programme and portfolio context. In addition, projects may be wholly managed within the commissioning organization or be part of a commercial relationship.

Projects can exist as stand-alone entities within an organization and outside the governance structures introduced by programmes or portfolios, or where an organization has been set up solely for the purpose of undertaking the project.

2.5.2 Projects within programmes

Definition: Programme

A temporary, flexible organization structure created to coordinate, direct and oversee the implementation of a set of related projects and activities in order to deliver outcomes and benefits related to the organization’s strategic objectives. A programme is likely to have a life that spans several years.

A project may be part of a programme, and the programme manager may commission a project to enable or deliver products or outputs that contribute to some of the programme’s expected outcomes. The project will be impacted by the programme’s approach to governance, its structure and its reporting requirements.

Tip

PRINCE2 defines the term ‘sponsor’ as the role that is the main driving force behind a programme or project. The guidance uses the term ‘commission’ for the activity or authority to request the project. The organization commissioning the project will usually provide the project sponsor.

2.5.3 Projects within a portfolio

Definition: Portfolio

The totality of an organization’s investment (or segment thereof) in the changes required to achieve its strategic objectives.

Corporate organizational structures can vary from ‘traditional’ functional structures to project-focused corporate organizations. In the ‘traditional’ functional structure, staff are organized by type of work (e.g. marketing, finance and sales) and there are clear reporting lines. In contrast, the standard practice in project-focused corporate organizations is to work with project teams.

Organizations may have corporate structures in which projects are commissioned to deliver products or outputs that contribute to the strategic objectives of the organization, and are managed within portfolios. A portfolio may comprise programmes, projects and other work that may not necessarily be interdependent or directly related but must all contribute to achieving the strategic objectives.

2.5.4 Projects in a commercial environment

If the project is being run to deliver to a specific set of customer requirements, the customer may have entered into a commercial relationship with a supplier following a formal tender. The organization delivering the project (the supplier) will do so in order to satisfy a particular need identified by the customer. The contract between the parties sets out how the customer and supplier will work together to deliver the project but the rights and duties covered by the agreement may constrain how a project manager manages the project.

The customer may break the work down into one or more elements. The number of elements is that which is necessary to deliver the customer’s business case. Some of those elements may then be used to procure suppliers to deliver that work, while others may form the basis of work to be delivered by the customer itself. For a supplier, the work to be delivered may be the subject of a legally binding contract resulting from the procurement process. In order to deliver this work, the supplier may itself procure subcontractors by further breaking down its work into additional elements.

In a commercial environment, sometimes there may be hierarchies of commercial relationships between suppliers. Rather than a simple customer/supplier relationship involving two organizations, projects often involve multiple organizations constrained by multiple contracts. There may be a primary commissioning organization (or one prime contractor), but there may be several customers and/or several supplier organizations, each of which may have its own business case for undertaking the project. Examples include:

•joint ventures

•collaborative research

•intergovernmental projects

•interagency projects (e.g. for the United Nations Development Programme)

•bidding consortium and alliance contracting

•partnerships.

When managing projects in a commercial environment, consider that there may be multiple sets of:

•reasons for undertaking the project (business case)

•management systems (including project management methods)

•governance (possibly requiring disclosure of different sorts of project data at different points in the project’s life)

•organization structures

•delivery approaches (see section 2.6.3)

•corporate cultures (e.g. behaviours, cultures, risk appetite).

Further advice and guidance related to tailoring PRINCE2 in a commercial environment can be found throughout this manual.

2.6.1 PRINCE2, international standards and bodies of knowledge

A standard provides rules, guidelines or characteristics that can be used consistently to ensure that materials, products, processes and services are fit for their purpose; it does not, however, state how activities should be carried out to achieve this.

A method, such as PRINCE2, provides not only a set of activities to be done, together with roles, but also techniques for undertaking these activities.

A body of knowledge looks at what a competent project manager should know and focuses on what and how to do it.

The PRINCE2 method exists within the context of a number of such standards and bodies of knowledge including:

•ISO 21500:2012 Guidance on Project Management (International Organization for Standardization, 2012)

•BS 6079–1:2010 Project Management. Principles and Guidelines for the Management of Projects (British Standards Institution, 2010)

•A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) (Project Management Institute, 2013)

•APM Body of Knowledge (Association for Project Management, 2012)

•The IPMA Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme & Portfolio Management (4th version, ICB4): an inventory of competences for individuals to use in career development, certification, training, education, consulting, research and more (International Project Management Association, 2015).

When designing and embedding a project management method based on PRINCE2 (see Chapter 4), an organization needs to be aware of these standards and bodies of knowledge, and should apply them in a manner appropriate to its business.

For more information about PRINCE2 and international standards, see Appendix B.

2.6.2 PRINCE2 and commissioning organization standards

An organization will typically develop values, principles, policies, standards and processes that are fit for purpose, including those required to govern, manage and support programmes and projects.

A programme defines its strategies in a plan which must ensure that the programme’s vision and goals align with those of the organization. Projects commissioned by a programme will typically inherit programme strategies which may be used to replace the project’s approach to quality management, risk management etc., tailoring them as appropriate.

If the project is commissioned by a customer from outside the project organization, then the mandate may require the use of some or all of the customer’s standards or methods. Examples may include the use of the customer’s issue management process and specific reporting requirements.

The project manager may need to tailor the project (see section 4.3) to meet standards and process requirements, but within the guidelines of the organization’s method. This will be recorded in the project initiation documentation (PID).

Tip

Varied uses of terminology can be particularly confusing where multiple best-practice methods are employed within the same organization, and care must be taken to map or integrate the methods.

2.6.3 PRINCE2 and delivery approaches

The project approach is the way in which the work of the project is to be delivered. It may rely on one or more delivery approaches, which are the specialist approaches used by work packages to create the products. Typical approaches include:

•a waterfall approach where each of the delivery steps to create the products takes place in sequence (e.g. in a construction project where requirements gathering and design take place before building begins) and the product is made available during or at the end of the project

•an agile approach often, but not exclusively, for software development where requirements gathering, design, coding and testing all take place iteratively through the project.

There are typically a number of delivery steps within the delivery approach (e.g. the sprints within an agile approach or steps such as study, design, build, test, etc. within a waterfall approach).

The application of PRINCE2 can be very different depending on which delivery approach is used. For further guidance, see sections 9.3 and 16.5.

Key message

PRINCE2 Agile regards agile as a family of behaviours, concepts, frameworks and techniques. For more information about using agile and PRINCE2 together, see PRINCE2 Agile (AXELOS, 2015).

The traditional approach to measuring time, cost and quality may still have its place but it does not necessarily tell the whole story. The best way to summarize the project status at a point in time is to identify key performance indicators (KPIs).

When designing KPIs, a balance should be struck between qualitative and quantitative measures, leading and lagging indicators, and project inputs and outputs. The number of KPIs should be balanced to create only information that is necessary and sufficient.

Key message

Objectives are what the project needs to achieve, whereas KPIs are the measures that indicate whether or not progress is being made towards achieving the objectives.

What are lagging and leading indicators?

Lagging indicators

Measure performance that follows events, and allow management to track how well actual performance matches that which was expected. An example could be the number of unexpected errors reported after a particular software release.

Leading indicators

Measure progress towards events, and allow management to track whether it is on course to achieve the expected performance. An example would be the persistent failure of a supplier to meet quality requirements early in the project.

The KPIs should be aligned with the quality expectations and acceptance criteria defined in the project product description, and the project tolerances (time, cost, quality, scope, benefits and risk) defined in the PID.

One way to show project progress is through a project dashboard that uses graphical representations such as pie charts and histograms to display the status and trends of performance indicators. These can show the status for quantitative KPIs and are easy to understand by relevant stakeholders at all levels.

2.6.5 PRINCE2 and organizational capability

It is generally recognized that organizations which demonstrate higher levels of project management capability can also demonstrate increases in business performance through the effective use of project management methods such as PRINCE2. Maturity models such as AXELOS Limited’s Portfolio, Programme and Project Management Maturity Model (P3M3) provide a way of baselining organizational capability against a maturity scale, diagnosing weaknesses and planning for improvements.

P3M3 characterizes an organization’s maturity using the following 5-point scale:

•Level 1: Awareness of process

•Level 2: Repeatable process

•Level 3: Defined process

•Level 4: Managed process

•Level 5: Optimized process.

An organization assessed at level 3 would typically ensure that a project management method such as PRINCE2 is consistently deployed and used by all projects (see Chapter 21). The organization’s embedded version of PRINCE2 may need to take account of the types and scale of project being delivered, the environment within which the organization operates (e.g. regulatory or commercial), commissioning organization standards and the delivery approach(es) used. The method may also allow for tailoring (see Chapters 4 and 21), perhaps within specific rules or guidelines, in order to recognize the differences specific to individual projects.