13. Max Foundation (A): Saving Children’s Lives Through Business Model Innovation

08/2011-5788

This case was written by Martijn Thierry, independent strategy consultant for profit and non-profit organisations, and Luk Van Wassenhove, the Henry Ford Chaired Professor of Manufacturing and Professor of Operations Management at INSEAD. It is intended to be used as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Mirte Gosker, Research Associate at INSEAD Social Innovation Centre.

Copyright © 2011 INSEAD

COPIES MAY NOT BE MADE WITHOUT PERMISSION. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE COPIED, STORED, TRANSMITTED, REPRODUCED OR DISTRIBUTED IN ANY FORM OR MEDIUM WHATSOEVER WITHOUT THE PERMISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER.

I. Creating Something Positive Out of a Tragedy

“We were so happy when Max was born. He always smiled and made friends everywhere.”

—Steven and Joke le Poole, Max’s parents

Before their son Max was born, Steven and Joke le Poole had built up their professional careers. Steven, a Harvard Business School graduate, had started his own private equity firm and Joke had worked as an interim manager for large Dutch companies, including Heineken. They had also found time for extensive travelling, from cycling in Asia to trekking in Africa and South America. Steven, an avid mountaineer, had climbed Cho Oyu (8,201m) in the Himalayas, without oxygen. During their travels they often visited areas where NGOs were active, “because we were interested to see in practice what was done with the money that we had donated.”

In March 2004, disaster struck when their 8-month-old son Max died from a rare viral infection. Although filled with grief, Steven and Joke were determined to create something positive out of the tragedy:

“Many people said ‘Don’t do this to yourself, save your energy.’ But we felt we had to do something with Max’s death; it could not stop there. We had to attach something positive to Max’s name. We wanted to do something that would ensure that fewer parents have to endure the tragic loss of their child.”

Max Foundation was founded in the summer of 2004 in the Netherlands, with the aim of combating child mortality. From the outset, Steven and Joke had clear ideas on how a social venture should operate. When they failed to find an NGO that conformed to these ideas they decided to set up their own venture. One of the key principles of Max Foundation was that 100% of donations would be spent on projects to reduce child mortality; no money would be spent on overheads in the Netherlands. This meant that Steven and Joke would have to continue their professional careers while running Max Foundation at the same time.

Was it a crazy idea, or would they defy the odds and be able to make a real impact in the fight against child mortality?

II. The Vision and the Search

From day one, Steven and Joke had a clear vision of how Max Foundation should work:

• We focus on where we have the largest impact on child mortality per euro spent

• We spend 100% of donor money on direct activities to reduce child mortality

• We give direct feedback to donors on how their money will be and has been invested

In addition, they were convinced that small, focused, entrepreneurial-style social ventures create ‘higher health value per euro spent’ than large NGOs with a broad scope of activities. Turning this vision into something tangible was the first challenge for Max Foundation, as Steven recalled.

“We had assumed that information on cost efficiency of measures to reduce child mortality would be readily available—that you could find it on the internet—but it wasn’t. And none of the NGOs that we spoke to had such information. They were not used to think in terms of linking costs to output.”

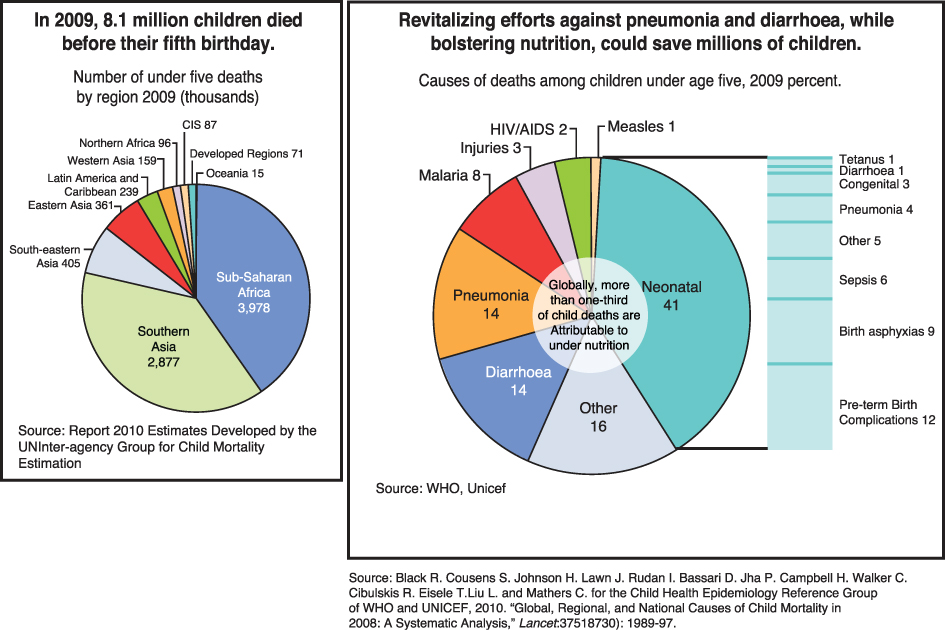

Publicly available information showed that over 8 million children under five years old die every year and that 98% of child mortality occurs in developing countries. It also showed that around 70% of these deaths are caused by infectious diseases (see Exhibit 1).

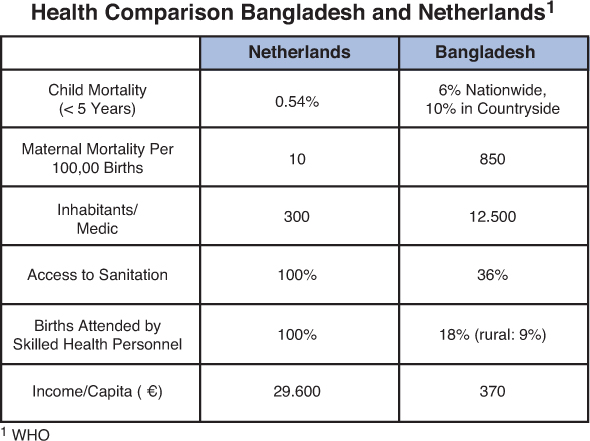

Steven and Joke started their own search for people in the Netherlands who had had first-hand experience of doing work in developing countries that involved children’s health. Using their personal network and the networks of people around them, within a few weeks they had compiled a list of 16 potential projects to support. None of these projects provided the ideal set of data, but that did not stop Steven and Joke from going ahead. Using five criteria (focus on children, focus on health, directness, effectiveness, and efficiency) and a simple quantitative scoring system, they identified a project in Bangladesh that was run by a local NGO called Aloshikha, involved in providing medical equipment to a hospital for mothers and young children in a rural setting with high child mortality. (See Exhibit 2 for a health comparison between Bangladesh and the Netherlands).

In January 2005, Steven received the first funding request from Bangladesh. All but one of the requested items were types of medical equipment, the most expensive being a ‘coagulation device’ costing €4,800 to seal blood vessels during an operation. Steven recalled:

“I wondered what the health impact of each piece of equipment was, and I asked: ‘How many lives each year are saved because of this coagulation device?’ The answer did not impress me.”

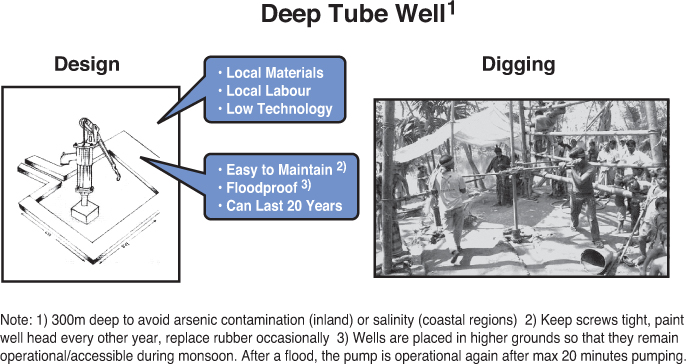

Then he asked about the only item on the list that was not medical. It was listed as ‘DTW’ and it cost €450.

“They told me this was a Deep Tube Well, a well that goes 300 metres underground to an unpolluted source of clean water. ‘Do many children die because they have no access to clean water?’ I asked. Yes, was the answer, many children die of diarrhoea and other water-borne diseases, and most die before they reach a hospital.”

Many shallow tube wells were built in the 1970s and 1980s, he was told, but these were often contaminated with arsenic that occurs naturally in the soil.

“Then I said: ‘How many people can use a DTW?’ About 200, was the answer. I started doing the maths. How many lives would a DTW save and at what cost? It was a Eureka moment. The numbers in favour of the DTW were so compelling.” (See Exhibit 3)

Steven and Joke had found a cause to start realizing their vision: preventing child mortality by providing clean water through DTWs in rural Bangladesh.

Now they needed to start implementation, both in the Netherlands and in Bangladesh. Knowing the value of including the ‘user community’ in implementation from their business experience, Steven and Joke were committed to involving the local Bangladeshi community in the implementation process.

“The local community has to show its commitment and has its own responsibility. We did not believe in giving away DTWs for free. By letting the community contribute to the establishment of a DTW, we create community pride and ownership.”

III. Building the Base in the Netherlands

The ‘no overheads’ model meant that Max Foundation had no paid staff. It worked only with volunteers willing to invest their personal time and money. The first board members and volunteers of Max Foundation came out of the group of people who knew Steven and Joke personally, and who knew the story of Max first hand. There was no formal organization.

One of the first volunteers was a marketing professional who worked at a leading FMCG1 company. He developed a so-called ‘brand key’ for Max Foundation. This emphasized ‘sincerity and transparency’, ‘having a positive impact’, and ‘small scale and direct’.

1 FMCG: Fast Moving Consumer Goods

Shortly afterwards, Steven and Joke developed the first donor proposition. For €350, donors could sponsor an individual DTW, which would be named after them. The donor would receive a picture of the DTW with their name on a signboard (see Exhibit 4)—the traceability of the money stream from donor to DTW was provided in this way. The local community would contribute €100 of the €450 total cost of the DTW.

With the help of volunteers and pro-bono support from a PR agency, Steven and Joke set about generating publicity that did not cost any money. Max Foundation website was launched, several articles appeared in national newspapers and magazines in the Netherlands, concerts were organized on behalf of the Foundation, and Steven and Joke made numerous presentations to various audiences, ranging from private funds to service clubs and companies.

At the beginning of 2005 they had been somewhat apprehensive about the ability of Max Foundation to raise funds. Memories of the terrible tsunami of December 2004 were fresh in everybody’s mind, and record-breaking amounts of money had been raised for the victims. But, as Steven said:

“At the same time, you sensed that many people wondered whether the money they donated was used in the right way.”

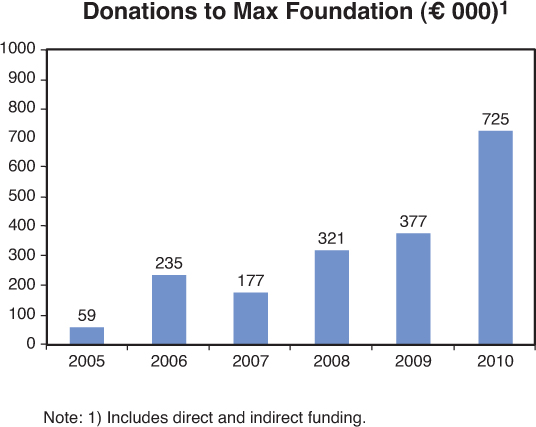

Max Foundation received many positive responses. It established 146 ‘fundraising contacts’ in 2005, growing to 453 in 2006. The amount raised was €58,917 in 2005—way above expectations, growing to €234,979 in 2006.

IV. The First Steps in Bangladesh: Learning While Doing

With the money that had been raised in the Netherlands, Aloshikha installed 50 DTWs in 2005. The technology of the DTW was proven and simple and the well could be made using local materials and local labour (see Exhibit 5). Aloshikha took care of the entire DTW installation process: selecting the areas where the wells were to be installed, working together with the local communities, giving training on DTW maintenance, procuring the materials, and managing the external contractors that dug the wells.

Through contacts in the Netherlands, Steven and Joke found a second local partner, SLOPB, which was active in the southern coastal area of Bangladesh and had no geographical overlap with Aloshikha. The proposal that SLOPB sent to Max Foundation included a request to support hygiene education and sanitary latrines in addition to the DTWs. This struck a chord with Steven. Through discussions with other NGOs in the Netherlands, and from reports by UNICEF and WHO, he realized that the programme would be improved if it combined DTWs, latrines and education, for which he coined the term ‘micro-sanitation’.

“I remember reading an interview with Bill Gates, where he said that investing only in ‘hardware’ is a beginner’s mistake. Micro-sanitation provides the combination of hard- and software with proven low-cost technology. We use simple latrines with a water-seal that is very effective against water-borne diseases, and that can be made locally at a cost of €10 to €12 per latrine.” (See Exhibit 6).

In June 2007, Steven attended a lecture by Michael Porter and Jim Yong Kim of Harvard University.2

2 Presentation by Michael Porter and Jim Yong Kim during Harvard Business School Reunion on June 2, 2007: “Redefining Global Health Care—Narrowing the Gap Between Aspiration and Action”

“They spoke about the millions of lives that can be saved using technologies that are already available, and they applied business thinking to the development sector. Most doctors, they said, are professionals that want to cure people and build hospitals. But if you look at the metrics, at the health-return-per-dollar-spent, prevention is often much more effective and cheaper than building hospitals. When I heard that, I knew we were on the right track as we were doing exactly that. Michael Porter’s advice to me was: ‘Use Max Foundation to set the agenda and influence others.’”

Over time, Max Foundation has developed an effective implementation process. Prior to starting micro-sanitation in a village, a site has to be selected for the DTW. The local partner facilitates this process and involves the entire village. A contract is drawn up with the landowner and the village, stipulating that a selected piece of land can be used for the well and that the site will be accessible to all people from the village. In addition, the village has to contribute around €100 to the cost of the DTW. The local partner contacts the main stakeholders, including religious leaders and local government officials, to inform them about the programme, answer any questions, and get their support for the project. In addition, the village needs to follow a hygiene education programme and appoint caretakers who will be responsible for the maintenance of the DTW. Tools and maintenance training are provided by the local partner.

In the course of 2006, Steven and Joke decided that Max Foundation should focus exclusively on Bangladesh. Their initial idea in 2005 had been to start a project in a different country every year. Candidate countries included Peru, India, Tanzania, Afghanistan, Cambodia, Kenya, El Salvador, South Africa, Guatemala and Burkina Faso. However, they realized that their approach was well suited to Bangladesh due to a combination of high child mortality through water-borne disease, a stable social structure, and a low cost of micro-sanitation. Inevitably there was a learning curve in each country. By staying in one country, they could move more quickly along the learning curve.

Max Foundation installed 59 DTWs in 2006, slightly higher than the 50 installations in 2005. Due to its fundraising at home there was enough money to install more DTWs in 2006, but the Foundation had to hold on to the funds as the local partners in Bangladesh were unable to scale up.

V. Challenges at Home

In 2006, Steven and Joke began to realize that the Foundation’s organization did not work well enough and needed to change. As Joke said:

“Sharing the same dream turned out to be not enough. We needed volunteers who were ‘functionally competent’ and ‘self-steering’ as we had neither the desire nor the time to control people. Steven and I had to learn how to manage a group of volunteers, ourselves included. We needed to build a balanced team of professionals with the different functional areas included.”

They began to use a formal recruiting process to evaluate candidates for positions—something they had not done before. A major change was the hiring of Jasper Vet as treasurer in 2007, which meant that Steven could delegate all financial aspects and had more time to spend on other areas. In the process, a number of volunteers left. In 2007, Max Foundation generated less publicity than in 2006, which had an impact on donations: at €177,188, the amount raised was 25% lower than in 2006.

Once the organizational problems were out of the way, growth picked up in 2008. New publicity was generated. A TV documentary was made on the first visit of Max Foundation to Bangladesh. The 2007 annual report, published in 2008, was a step change improvement that rivalled many professional companies in terms of clarity and transparency. In 2008, Max Foundation received an award for best public relations in the ‘private development initiatives’ category in the Netherlands.

Donations in 2008 amounted to €321,341, almost double the 2007 total. They increased again in 2009 to €376,711. The number of fundraising contacts rose from 605 in 2007 to 1,349 in 2009.

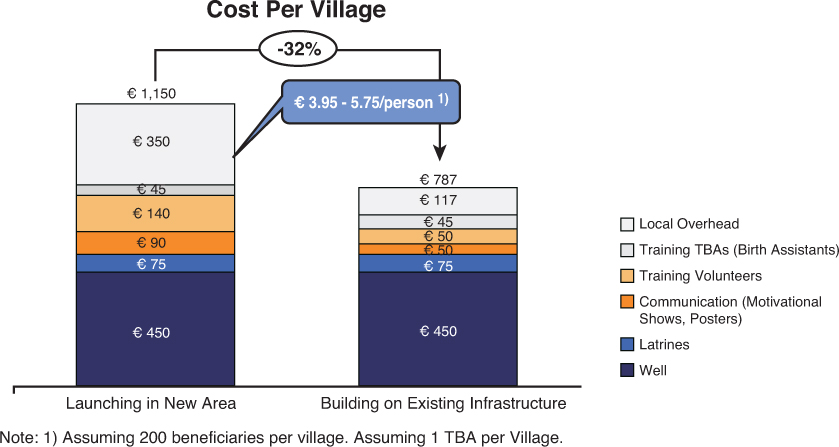

In 2009, Max Foundation launched a second donor proposition. For €1,150, a donor could sponsor the entire micro-sanitation implementation in a village of around 200 people, covering the installation of a DTW (with a personalised signboard), the installation of latrines, and hygiene education. The target groups for this proposition were primarily companies, private funds and service clubs. Individual donors remained the main target for the original DTW proposition.

Despite the growth in donations, Steven felt some frustration:

“We often hear that what we are doing is not innovative, and therefore our request for funding is rejected because we do not use technologically innovative filters and other high-tech equipment—that we know is much too expensive for what it delivers in comparison to our approach. And sometimes we are rejected because they say we are too small; only organizations with a minimum annual income stream of, for example, €1 million are considered. And even worse, sometimes we are rejected because we are thought to be ‘too successful’ and thus ‘don’t need the money’—while we can show that demand in Bangladesh is huge.”

The year 2009 saw the re-launch of Max Foundation website. In addition, Steven and Joke, with help from many volunteers, organized a debate in Amsterdam on the effectiveness of development aid. It was attended by 400 people, including many of the established NGOs in the Netherlands.

Throughout 2009 and 2010, they became increasingly aware that time is the greatest obstacle for an organization run solely by volunteers, many of whom have professional careers at the same time. A significant step forward was the standardization of the process for handling donors of a DTW: from sending a ‘thank you’ letter, to tracking payment status, to sending the picture of the DTW signboard with their name on it.

Another improvement was the restructuring of Max Foundation in 2010 into ‘work-clusters’: groups of people responsible for ‘communication NL’, ‘fundraising’, and ‘partners Bangladesh’. Each cluster involved two board members with a clear definition of responsibilities. The restructuring created more focus in the work of the different board members and saved time. Within their cluster, board members worked with other volunteers and with the companies that supported Max Foundation on a pro-bono basis, such as the PR company, the website builder, and the accounting firm that audited the annual report. Steven operated as chairman, overseeing all developments. He acknowledged:

“We want to add more volunteers in order to get more things done and to keep innovating.”

VI. Increasing Presence in Bangladesh

As indicated, in 2006 Max Foundation had not installed as many wells as it had wanted because the two local partners did not have the capacity to scale up. The problem was resolved when a new partner, Aungkur, was found in 2007. Like Aloshikha and SLOPB, Aungkur employed only local staff, did not hire expensive expats, and had a good reputation in the local community. In terms of size the three organizations were similar, with a maximum of 300 employees each. They all offered other services to the local community such as micro-credit, but these were not funded by Max Foundation.

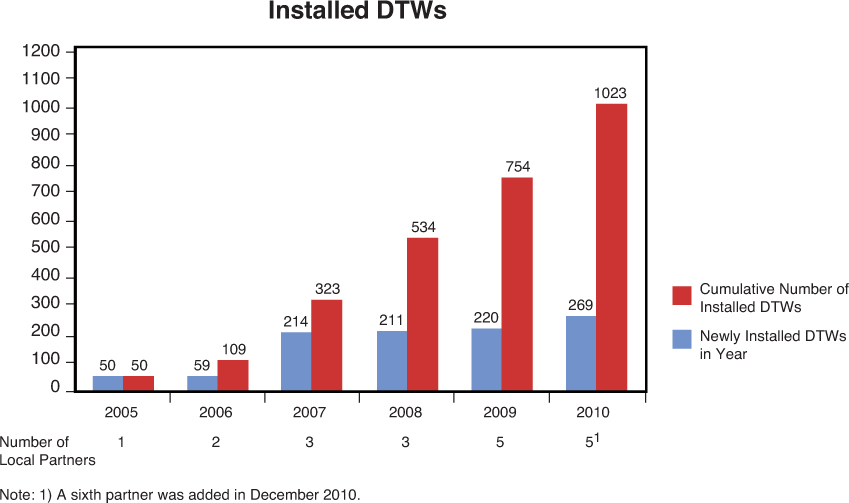

A total of 214 DTWs were installed in 2007, more than triple the number in 2006. In 2008, 211 DTWs were installed, rising to 220 in 2009. Two new partners, BDS and Paras, started micro-sanitation programmes with Max Foundation in 2009. In 2010, 269 DTWs were installed (see Exhibit 7).

In 2008, a delegation from Max Foundation, including Steven, Joke and Jasper, made a first visit to their local partners in Bangladesh and to the villages where the micro-sanitation approach had been implemented. Steven recalled:

“During our first visit we were there to learn and see what was happening. In all villages that we visited—many without informing the local partner beforehand—we saw that the DTWs were in good working order and were being actively used.

We also saw that the caretakers for the DTWs were mostly women and that women are essential in changing hygiene behaviour. Many villages had health committees, set up by the local partners, which consisted of virtually only women. Interestingly, many of the women in these committees were also the ones taking micro-credit.

People said that they felt much better now. They also said that their children were not dying of diarrhoea any more. That was such a great message to hear.”

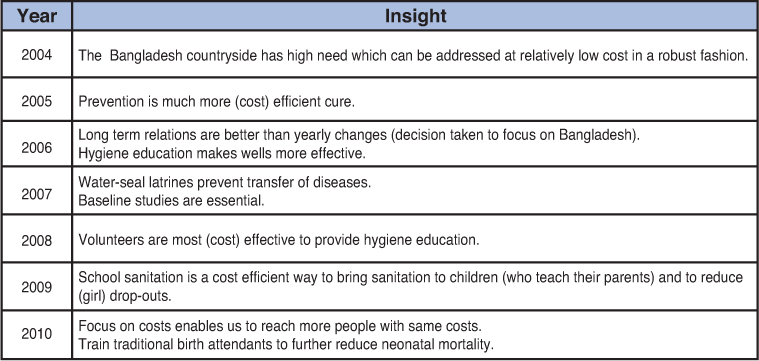

Since 2008, a delegation from Max Foundation has visited Bangladesh at least once a year. Each visit provides new insights that are incorporated into the Foundation’s programme (see Exhibit 8). School sanitation, with separate sanitary latrines for girls and boys, was added in 2009 as a cost-efficient way to bring sanitation to children, who in turn teach their parents. A welcome side-effect is that it reduces the school drop-out rate among girls.

The visits in 2010 were a turning point in the relationship between Max Foundation and its local partners, as Steven recalled:

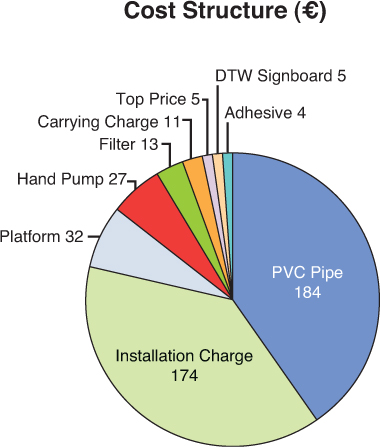

“2010 was different to previous visits; we could challenge partners and tell them things they did not know. For instance, we had found out that there was a 30% cost difference between partners in the cost of procuring PVC pipes, which is the largest single cost element in DTW installation. We could tell our local partners what cost level was possible, and that they should procure the PVC pipes directly from the manufacturer instead of from a distributor. With the money that they saved in this way we asked them to install additional DTWs. Our signal to them was: ‘When you come with ideas to reduce costs, we do not take the money away from you but offer our support for you to do more.’”

In 2010, the training of traditional birth assistants (or TBAs) was added to Max Foundation agenda. A majority of pregnant women in rural Bangladesh are not seen by a trained nurse or birth attendant during pregnancy. Around 90% of women give birth without a nurse or birth attendant present. Both situations create high risks for mother and child and are a major cause of death. By training new TBAs and providing them with a basic medical kit—costing around €45 per TBA—the Foundation added a new element in its toolbox to reduce child mortality. A welcome corollary was that it reduced maternal mortality.

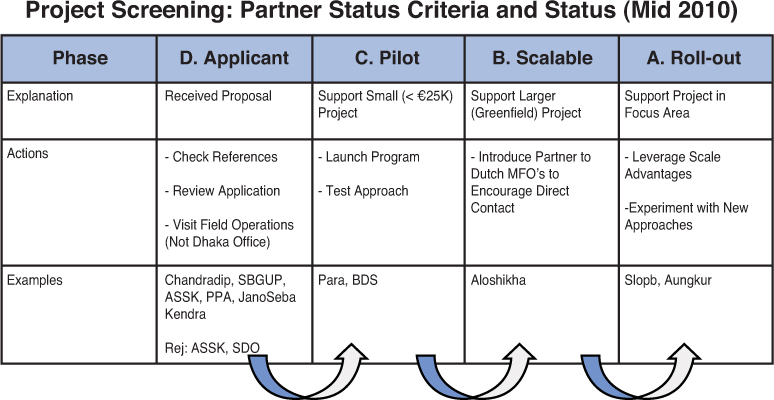

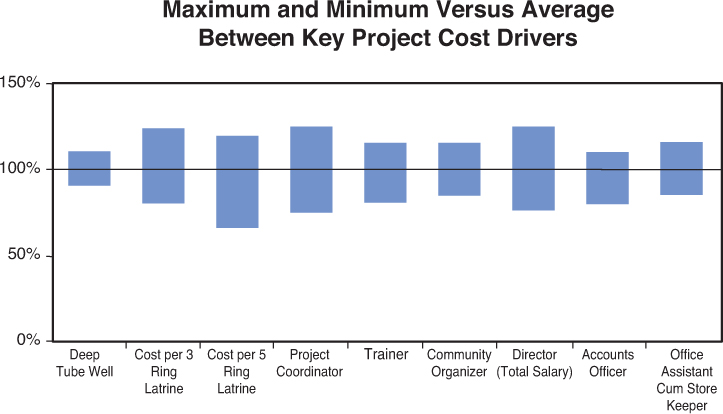

Max Foundation also became more disciplined in the management of local partners. A more structured process was developed for partner screening and roll-out (see Exhibit 9). In addition, guidelines were put in place on how to implement micro-sanitation, including the use of baseline studies at the start of a project, a monitoring process, and specific instructions on the location of DTWs. Costs were benchmarked on a detailed basis (see Exhibits 10 to 12).

In 2010, Max Foundation organized the first meeting between all the local partners in order to share best practices and stimulate collaboration. (Exhibit 13 shows the position of Max Foundation as the ‘added-value intermediary’ between donors and partners).

VII. Envisioning the Next Step

Steven and Joke made it happen.

The organization that they built up has provided clean water, sanitation and hygiene education to over 200,000 people in rural Bangladesh since 2005 and has saved many children’s lives. A survey in 2010 by NCB, a specialised consultancy in Bangladesh, provided strong indications that Max Foundation programme is working, reporting a 70% reduction in child mortality three years after micro-sanitation (compared with the period before its introduction) in 12 villages.

Steven and Joke showed that it is possible to create a significant impact in the fight against child mortality in a low-cost way by being innovative, that is, by doing things differently. The innovation has not been in product technology—developing or using products with unique characteristics—but in building a system that includes many innovative elements.

What are these innovative elements? How do they help Max Foundation to generate more impact? Can they be replicated by other organizations in the humanitarian sector? How much more impact could other humanitarian organizations generate with these innovative elements?

For Steven and Joke, the journey does not end here:

“We want to become the reference point in micro-sanitation; the organization that everybody knows and values. We want to grow to the next level, increase the number of partners, and have a larger impact.”

Together with all the people helping Max Foundation they are determined to make it happen. These challenges will be different from those faced in 2004, and there are multiple paths to choose from. What is the best route forward?

Exhibit 10 Micro-sanitation benchmark cost at €790 to 1,150 per village or ~ €3.95 to 5.75 per person

Exhibit 13 Current position of Max Foundation as “added-value intermediary” between donors and partners

Appendix 2

Additional Information on the Implementation Partners in Bangladesh

Overview

Many similarities exist between the implementation partners of Max Foundation in Bangladesh. All partners operate as a NGO, making no profit. The mission of each partner is to improve the lives of poor and disadvantaged people in the rural areas of Bangladesh. In addition, all partners use a variety of programmes to achieve their mission. Besides micro-sanitation, they have all implemented programmes for micro-finance and for education and training. In terms of size, all partners have less than 300 employees. They employ only local staff and do not hire (expensive) expats.

The implementation partners are active in different regions across Bangladesh. In all of these regions there is a relatively high percentage of poor people and a lack of clean water and sanitation facilities.

1: PARAS 2: Aungkur 3: Aloshikha 4: BDS 5: SLOPB

Some Partner Specific Information

Aloshikha Rajihar Social Development Centre (Aloshikha) was founded by the Bangladeshi family Halder. The organisation is based in Rajihar, an area 200 km south of Dhaka which is regularly hit by floods. Aloshikha has a basic health clinic for mothers and children. In 2009, 64 of the 163 employees worked in the education programme, which included 40 pre-schools and 10 primary schools for children’s education. The micro-finance programme employed 33 of Aloshikha’s staff while 31 employees worked in micro-sanitation. For additional information: www.aloshikhabd.org.

Aungkur Pali Unnayan Kendra (Aungkur) was founded by Mr Ayub Talukder, a Bangladeshi landowner. Aungkur provides various training programmes, both in the field and in its own training centre. Training programmes include topics such as health and nutrition, disaster management, and the training of volunteer groups. In 2009, Aungkur had 67 employees, of which 36 worked in micro-finance (proving credit to 57.526 women in Madaripur) and 21 in micro-sanitation. For additional information: www.aungkur.org

Stichting Land Ontwikkelings Project Bangladesh (SLOPB) was founded by Mr Motalib Weijters, a Dutch businessman who was born in Bangladesh but raised in the Netherlands by his Dutch adoptive parents. SLOPB has two orphanages and a basic health clinic for mothers and children. Between 1997 and 2009, SLOPB installed a cumulative number of 1.559 DTW’s. For additional information: www.slopb.org

Bangladesh Development Society (BDS) operates in the southern coastal area of Bangladesh. In 2009, 169 of the 289 employees worked in micro-finance. BDS did not have prior experience in micro-sanitation before its first project with Max Foundation in 2009.

Palli Rakkha Sangstha (PARAS) is active in the Sirajganj district, an area 150 km northwest of Dhaka that is densely populated and prone to flooding, due to the presence of the Jamuna river. PARAS has an education programme for children aged 8 to 14 that dropped out of school and offers training programmes on multiple topics including forestry and agricultural skills, health and nutrition, and disaster management.