Foundations for success in designing training

What should good training design incorporate as part of its DNA upon which the detail is layered? Think for a moment about how you might approach the design of some business training. What are your preferences? Where do you start? What do you use as a ‘test’ for effective design?

For a lot of us, the answers to these questions will not be clear. We may feel that it is about focusing on the needs of the learner, or that we need to stretch and challenge them in some cases, or perhaps that we need to cover some core information but we may not consciously be aware of the principles that are guiding us.

You might be designing training to achieve a variety of outcomes including bringing about a behaviour change, the development of a skill, the transfer of knowledge or creating understanding and motivation. In the following section we will look at principles to apply as you build the foundation of successful training design.

We will cover each of these principles in more detail, and later we will look at their practical application. Remember that they are principles which should guide, inform and challenge your thinking.

It’s all about linking to business performance improvements

Never lose sight of the fact that all business training must be in the service of achieving business outcomes. These outcomes should drive the design of any training, whether this is raising participant confidence, transferring knowledge or developing skills. Needs analysis will focus on specifying the ‘change’ required but as an effective training professional you need to learn that training design must:

- maintain the link between training objectives and the business need they fulfil;

- focus on what must happen so that the learning is transferred to the work environment.

Training that equips participants with the right knowledge or skills but does not result in transfer of this learning to the work environment is not serving the business outcomes. In this respect, the business training must, in a very practical sense, focus on the needs of the participants. Instead of just answering the question ‘What do participants need to learn or be able to do to realise the business change we need?’ we should also be asking ‘What do they need in order to transfer this learning to the work environment?’ To answer only the first question misses the point of business training – it is about applying the learning.

Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes need to be defined early on in your design process and will link training to business outcomes. Many trainers focus on an agenda but this is simply a road map of what is being covered in the training. An agenda does not tell participants what they will learn and it should not drive the design – the learning outcomes should.

Learning outcomes must be active in their language. You need to be able to finish the statement: ‘At the end of this session, participants will be able to ...’. This is likely to be a combination of:

- ‘be able to understand/know how to ...’

- ‘be able to apply ...’

- ‘be able to commit to ...’

A successful structure is clear and effective

Structure in your training design can bring clarity, logic and be an effective aid to retention and understanding. Think about the structure early on – get the big picture first and then look at each ‘chunk’ in more detail.

Structuring training design has two parts:

- Structure of the business training – the big picture:

- What needs to be included in terms of sessions to meet the objectives?

- In what order do you need to cover the material?

- Structure within each session of the training:

- What needs to be included in each session?

- What training methods will I use?

- What is the chronology of the session?

Also think about any materials you use such as handouts, manuals and slides so that they are easy to follow and use.

When planning your training design, think about the following questions:

- What structures make most sense for this business training? Does it flow in a logical way?

- What content needs to be covered in what order? How is this content best broken down into sessions?

- How does each session flow? Is there enough variety?

- What level of detail do I need to go into in the training? What level of detail do I need in any accompanying notes or handouts?

Creating awareness, responsibility and motivation in participants

Awareness, responsibility and motivation have very different meanings but we are going to link them together because they are the key principles underpinning all great training design.

Let us look at some basic definitions and then explore their importance.

DEFINITIONS

- Awareness: the knowledge or perception of a situation or fact. This extends into self-awareness, an understanding of your own views, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours.

- Responsibility: the opportunity or ability to act independently. You can think of it in another way: ‘response-ability’, the ability to choose a response in a given situation. This sense of individual choice is often critical if learning is to be applied.

- Motivation: a reason for acting or behaving in a particular way. People tend to do things because they want to. People are often motivated either towards things that they like or away from things that they want to avoid.

At the heart of these concepts is the idea of choice. An individual is making choices all the time: what to pay attention to, how to behave in a given situation, what to do or not do. If someone feels they have choice, they can consider options more objectively and will often be more motivated to follow through on the choice they make.

In the business world in all but a very few cases, such as compliance with a piece of legislation, the individual will have some element of choice over whether they take the actions we want them to take.

Let us look at influencing skills training as an example. We are seeking to design a programme which will develop key skills so participants may ethically influence their clients more effectively.

Before we can expect a participant to develop these skills we need to raise their awareness as to their relevance and importance. Each participant will have existing beliefs, preferences and views and if they do not have an awareness of these beliefs and preferences it may prevent them from applying any new skills. Once they are aware of this situation, we want any training design to help participants to understand that they do have a ‘response-ability’, a choice, and can respond in an influencing situation differently from how they respond now. Finally, we want them to transfer the learning into their world and use it with their clients. For this to happen, the training design needs to address the issue of individual motivation: to what extent will their learning help them achieve relevant goals or outcomes and/or help them avoid certain unwanted outcomes?

Think about the following when you approach the design:

- What beliefs, views or attitudes might participants have towards the topic and content of this business training? Are these likely to support or detract from its possible success? What do I need to do about this in design? It is important that you check these with participants rather than make an assumption of what their beliefs and views might be!

- What are the participants doing now relative to this topic or content? What are their ‘habits’? Why are they doing them?

- What are the specific key points I want participants to be aware of?

- What is in it for them? What will taking the desired actions give them and what will it help them avoid? Is this compelling enough? If not, what would motivate them more?

Recognise that people learn differently

Learning styles are such an important aspect of design and delivery that the next chapter focuses solely on them. But remember that you will have a preferred learning style which may affect your view of training design. In addition, your participants will have a variety of learning style needs, some of which will be very different from yours.

Learning styles (discussed in more detail in Chapter 8) are critical because your design should reflect the different needs of all of your participants. These needs will surface in different ways:

- Some will want to dive straight into practical application whilst others will want to consider things and understand theory.

- Some will ask lots of questions and others will quietly reflect.

- Some will need lots of detail and others will be comfortable with big picture facts.

So central to your design challenge is creating something that appeals to all styles.

Some things to consider:

- Think about the extent to which you can bring variety to training to appeal to different learning styles – activists, pragmatists, theorists and reflectors.

- How will you structure the training and communicate information in a way that appeals to ‘big picture’ and ‘small detail’ people? (This is a concept called chunking and is discussed in Chapter 9.)

- How much time is available and what is practically possible for you?

Some questions to think about:

- How can I integrate a variety of learning styles within the design?

- What different training methodologies and activities are available to me and what would be the most effective way to implement these to achieve the desired outcomes?

- How will I ‘chunk’ the training content to ensure clarity for all?

Managing the emotional state of the audience

Have you ever attended training that you were not looking forward to? Maybe you had a huge ‘to do’ list and the training was interfering with it, or maybe you did not believe the training would do any good. Perhaps you felt anxious about what was going to be covered and whether you would be able to understand it.

All of these feelings are natural. Depending on the topic and content of the business training you might see emotions from enthusiasm through to disdain, from engagement through to disinterest.

The worst mistake is not acknowledging how participants feel. The second worst mistake is then choosing to do nothing about it! Training design has to be about more than just the content.

What state of mind do you need to be in to learn effectively? We suggest that a state of ‘curiosity’ would be very useful. How would your learning be affected if, rather than feeling ‘curious’, you felt the training was a ‘waste of time’?

A key principle in design is to consider three things:

- What emotional state are participants likely to be in when they walk into the room? What might they feel about attending this training session and about the topic generally?

- What do I want them to feel when they leave the room? What is necessary for them to feel if we are to maximise the chance of achieving our desired outcomes?

- What do I need to do to move them from where they are to where I need them to be?

Later in this book we provide a number of practical tips and techniques to help create the state you want in your audience.

Some useful questions to consider:

- What emotional state, feelings or beliefs might the participants have when attending this business training?

- What do I need to do about this at the start of the training?

- What do I want them to feel at the end of the training? Is this realistic?

- When designing the programme how will I reflect the movement in emotional state or feeling that I want to achieve?

Adopt an attitude of continuous improvement

Some business training programmes will be ‘one-off’ events – a single training session to cover a specific topic, and you may never need to deliver it again. However, in most cases the business training will need to be delivered a number of times, quite often to new joiners or in different locations: for example, a compliance training session that all employees in a factory might need to attend or an ‘effective consulting skills’ or business development programme that needs to be rolled out to all relevant people within an organisation.

Whenever you design business training that is being delivered more than once, a key principle that you need to have is an attitude and approach of continuous improvement. This concept is widely used in other aspects of business such as manufacturing – the kaizen approach adopted by Toyota – but we have seen much less of it within the context of training design. With significant investment being made in the training, the cost of having participants attend and the need to achieve business outcomes, it would seem commonsense to take a continuous improvement approach. Sadly, it seems, commonsense in this area is not too common!

Adopting an attitude and approach of continuous improvement in training design will:

- make us more likely to look for the tangible results of our training – to see how effective it is;

- help ensure we respond to any changes we see in the business, the market or the internal working environment;

- raise our awareness about what is working and what needs to be changed – not just in the training course itself but within the wider context;

- help us be seen as performance specialists and business results focused by our peers and management;

- increase the chances of incremental improvements in the results we achieve.

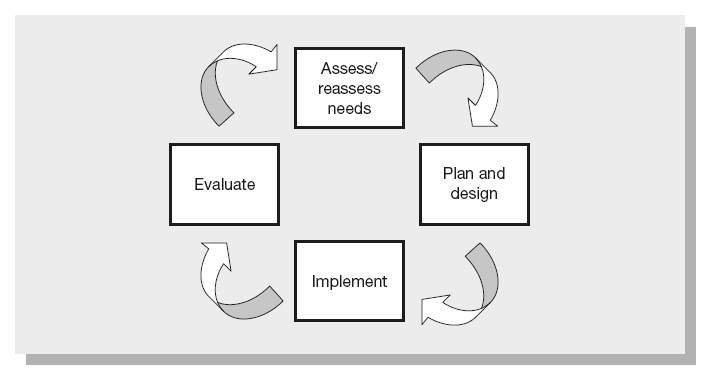

To ensure that your training design consistently has an approach of continuous improvement, you will need to apply the model shown in Figure 7.1.

Adopting a practical continuous improvement approach will involve key steps:

- From the start intend to review and improve the programme on a continuous basis – it is not a ‘one-off’ design. Communicate this to stakeholders, line managers and sponsors, gain their buy-in by sharing the benefits. Help them understand what this requires of them in terms of their own analysis and review of programme success, and be aware of any barriers that prevent application of the learning in the workplace.

- Design a formal review process that might include check points with participants, their line managers and business sponsors.

- Consider multiple check points. Check in with participants immediately after the training to get a sense of how confident they feel about applying what they have learned, what the barriers might be, what their view of the training was – what worked, what could be changed and why. Give time for the skills or learning to be applied by participants and check with them and their managers by looking more specifically at what has been implemented, what would help ensure that more of the learning was transferred and so on.

- Objectively assess the data from these check points and review the design, implementing changes that are supported by the data and evaluation.

Figure 7.1 Kaizen: a continuous improvement cycle

Questions to think about:

- What process for continuous improvement would be most effective?

- How many check points, and at what time intervals, would be appropriate? Why?

- What, specifically, will I evaluate and how will I do that (formal, informal, data, anecdotes, etc.)?

And finally, before we forget ...

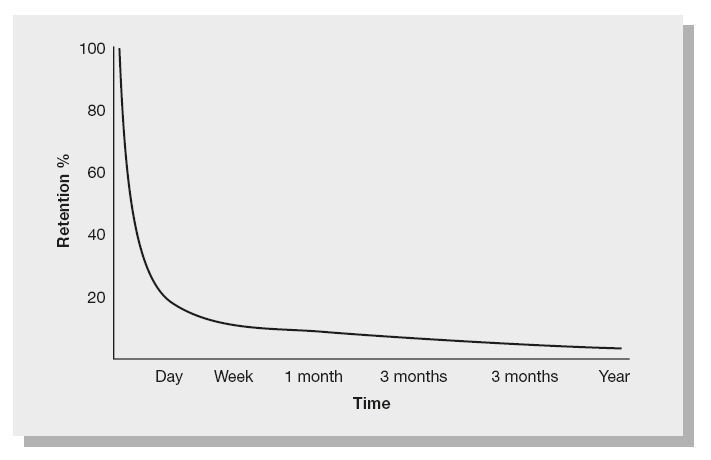

In 1885 Hermann Ebbinghaus theorised that humans tend to halve their memory, or ability to recall, newly acquired knowledge in a matter of days or weeks. Being aware of this concept – shown in what is called the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve (see Figure 7.2) enables you to plan to minimise this effect.

Figure 7.2 The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve

In your design you must plan to maximise retention through opportunities for practice, review and repetition both during and after a training course.

Summary

By paying attention to a few key principles as you approach the design phase you will maximise the chances of participant engagement as well as the achievement of your desired outcomes.

- Behaviour change requires the individual to have awareness, take responsibility and be motivated. Training design must address these three elements.

- Individuals have different learning preferences. Design your training to incorporate these different styles.

- Recognise that you will have a preference for learning and this can affect your approach to design. Challenge yourself to design for the learners.

- Make sure the structure of your training design is logical and flows well.

- Consider the feelings of participants as they enter the room. Plan what you need to do to have them motivated to change behaviour when they leave.

- Take a ‘continuous improvement’ approach to training.