11

PLANNING AND CONTROL OF PLANT AND EQUIPMENT OR CAPITAL ASSETS

IMPACT OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURES

Capital expenditure planning and control are critical to the long-term financial health of any company operating in the private enterprise system. Generally, expenditures for fixed assets require significant financial resources, decisions are difficult to reverse, and the investment affects financial performance over a long period of time. The statement “Today's decisions determine tomorrow's profits” is pertinent to the planning and control of fixed assets.

Investment in capital assets has other ramifications or possible consequences not found in the typical day-to-day expenditures of a business. First, once funds have been used for the purchase of plant and equipment, it may be a long time before they are recovered. Unwise expenditures of this nature are difficult to retrieve without serious loss to the investor. Needless to say, imprudent long-term commitments can result in bankruptcy or other financial embarrassment.

Second, a substantial increase in capital investment is likely to cause a much higher break-even point for the business. Large outlays for plant, machinery, and equipment carry with them higher depreciation charges, heavier insurance costs, greater property taxes, and possibly an expanded maintenance expense. All these tend to raise the sales volume at which the business will begin to earn a profit.

In today's highly competitive environment, it is mandatory that companies make significant investments in fixed assets to improve productivity and take advantage of the technological gains being experienced in manufacturing equipment. The sophisticated manufacturing and processing techniques available make investment decisions more important; however, the sizable amounts invested allow for greater rewards in increased productivity and higher return on investment. This opportunity carries with it additional risks relative to the increasing costs of a plant and equipment.

These conditions make it imperative that wisdom and prudent judgment be exercised in making investments in capital assets. Management decisions must be made utilizing analytical approaches. There are numerous mathematical techniques to assist in eliminating uneconomic investments and systematically establish priorities. Since these investment decisions have a long-term impact on the business, it requires an intelligent approach to the problem.

CONTROLLER'S RESPONSIBILITY

What part should the controller play in the planning and control of capital commitments and expenditures? The board of directors and the chief executive officer (CEO) usually rely on first-level management to analyze the capital asset requirements and determine, on a priority basis, which investments are in the best long-term interests of the company. The controller has a key role to play in making the determinations. All the functional departments, like sales or manufacturing, will have valid reasons for expansion or cost savings through the purchase of new plant and equipment. In addition, each operating unit will have a real need to increase the capital asset expenditures to meet its goals and objectives. The controller, with the financial knowledge of all company operations, should be able to apply objectivity by making a thorough analysis of the proposed expenditures. In many cases, heavy losses have been incurred because the decision was made with an optimistic outlook but without adequate financial analysis. The responsibility is placed on the controller's staff to make an objective appraisal of the potential savings and return on investment. The board of directors and the CEO must have a proper evaluation of proposed expenditures if they are to carry out their responsibilities effectively.

After the decisions have been made to make the investments, the controller must establish proper accountability, measure performance, and institute recording and reporting procedures for control.

The following is a list of thirteen functions that relate in some way to the planning and control of fixed assets and that typically come within the purview of the controller:

- Establish a practical and satisfactory procedure for the planning and control of fixed assets.

- Establish suitable standards or guides, also called hurdle rates, as to what constitutes an acceptable minimum rate of return on the types of fixed assets under consideration.

- Review all requests for capital expenditures, which are based on economic justification, to verify the probable rate of return.

- In the context of the business plans—whether short term or long range—ascertain that the plant and equipment expenditures required to meet the manufacturing and sales plans (or plans for research and development [R&D] or any other function) are included in such plan, and that the funds are available.

- As required, establish controls to assure that capital expenditures are kept within authorized limits.

- As requested, or through initiative, review and consider suitable economic alternatives to asset purchases, such as leasing or renting, or buying the manufactured item from others—a part of the “make-or-buy” decision.

- Establish an adequate reporting system that advises the proper segment of management on matters related to fixed assets, including:

- Maintenance costs by classes of equipment

- Idle time of equipment

- Relative productivity by types or age of equipment and so forth

- Actual costs versus budgeted or estimated costs (as in the construction or purchase of plant and machinery, etc.)

- Design and maintain property records, and related physical requirements (numbering, etc.) to accomplish:

- Identifying the asset

- Describing its location, age, and the like

- Tracking transfers

- Properly accounting for depreciation, retirement, and sale

- Develop and maintain an appropriate depreciation policy for each type of equipment—for book and tax purposes, each separate, if advisable.

- Develop and maintain the appropriate accounting basis for the assets, including proper reserves.

- Ascertain that proper insurance coverage is maintained.

- See that asset acquisition and disposition is handled in the most appropriate fashion taxwise.

- Ascertain that proper internal control procedures apply to the machinery and equipment or any other fixed asset.

While the controller and staff have certain accounting, evaluation, auditing, and reporting requirements to meet, it should be understood that the line executives have the major responsibility for the acquisition, maintenance, and protection of the fixed assets.

CAPITAL BUDGETING PROCESS

Having mentioned the responsibilities related to fixed assets that are typically assigned to the controller, we devote the principal part of this chapter to the capital budgeting process. Most of the accounting and reporting duties are known to the average controller, but more involvement in the budget procedure needs to be encouraged. Given the relative inflexibility that exists once capital commitments are made, it is desirable that the CEO and other high functional executives be provided a suitable framework and basis for selecting the essential or economically justified projects from among the many proposals—even though their intuitive judgment may be a key factor. And when the undertaking begins, the expenditures must be held within the authorized limits. Moreover, for the larger projects at least, management is entitled, once the asset begins to operate, to be periodically informed how the actual economics compare with the anticipated earnings or savings.

The sequential steps in a well-conceived capital budgeting process are outlined below. It should be understood that these steps are not all performed by the controller, but rather by the appropriate line executive. (In separate sections, some of the more analytical facets are explored.)

- For the planning period of the short-term budget, which may be a year or two, deter-mine the outer limit or a permissible range for capital commitments or expenditures for the company as a whole, and for each major division or function. This is desirable so that the cognizant executive has some guidance as to how much he can spend in the planning period. (There must be a starting point, and this is as good a one as any.) Depending on the circumstances, this may be an iterative procedure.

- Through the appropriate organizational channels, encourage the presentation of worthy capital investment projects. For major projects, the target rate of return should be provided, and any other useful guidelines should be furnished (corporate objectives, plans for expansion, etc.).

- When the proposals are received (and presumably there are many) make a preliminary screening to eliminate those that do not support the strategic plan, or that are obviously not economically or politically supportable.

- After this preliminary screening:

- (a) Classify all projects as to urgency of need.

- (b) Also, calculate the supposed economic benefits. Those performing this task must be given guidance as to (1) the method of determining the rate of return and (2) the underlying data required to support the proposal.

- When the data on proposed projects are submitted for top management approval, the financial staff should review and check the material as to:

- (a) Adequacy and validity of nontechnical data

- (b) Rate of return and the related calculations

- (c) Compatibility with

- (i) Other capital budget criteria

- (ii) Financial resources available

- (iii) Financial constraints of the total or divisional budget and so forth

- When the proposals have been reviewed and analyzed, and approved by top management, the data must be presented to the board of directors and approval secured in principle.

- When the time approaches for starting a major project, the specific authorization should be reviewed and approved by the appropriate members of management. This process may require a recheck of underlying data to be sure no fundamentals have changed.

- As a control device, when a project has started, periodic reports should be prepared to indicate costs incurred to date, and estimated cost to complete—among other information deemed critical.

- At stipulated times, and for a stated period, after a major project has been completed, a post-audit should be made comparing actual and estimated cash flow.

As can be deduced, the role of the controller and staff as to capital budgeting relates to the financial planning, the establishment and monitoring of the capital budgeting procedure, the economic analyses, and the control reports during and after completion.

ESTABLISHING THE LIMIT OF THE CAPITAL BUDGET

A common beginning point in the annual planning process is to set a maximum amount that may be spent on capital expenditures. There will be occasions when the “normal” limit is set aside because of an unusual investment opportunity or other extraordinary circumstances. Normally, however, top management will set a capital budget amount, based on its judgment and considering such factors as:

- Estimated internal cash generation (net income plus depreciation and changes in receivables and inventory investment, etc.)

- Availability and cost of external funds

- Present capital structure of the company (too much debt, etc.)

- Strategic plans and corporate goals and objectives

- Stage of the business cycle

- Near- and medium-term growth prospects of the company and the industry

- Present and anticipated inflation rates

- Expected rate of return on capital projects as compared with cost of capital or other hurdle rates

- Age and condition of present plant and equipment

- New technological developments and need to remain competitive

- Anticipated competitor actions

- Relative investment in plant and equipment as compared to industry or selected competitors

At different times, each of these factors will seem more compelling than others. As an additional rule of thumb for “normal” capital expenditures, some managements determine the limit based on the (a) amount of depreciation, plus (b) one third of the net income. The remaining two thirds of net income are used equally: one half for dividend payout to shareholders, and the other half for working capital.

In considering the company investment in plant and equipment versus the industry, these two ratios may provide some guidance:

- Ratio of fixed assets to net worth. This ratio, when compared with those of competitors, indicates how much of the net worth is used to finance plant and equipment vs. working capital.

- Turnover of plant and equipment. The ratio of net sales to plant and equipment, when compared to industry data, to specific companies, or to published ratios such as those issued by Dun & Bradstreet, shows whether too much is invested in fixed assets for the sales volume being achieved.

INFORMATION SUPPORTING CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PROPOSALS

An important element in a sound capital budgeting procedure is securing adequate and accurate information about the proposal. In this connection, the reason for the expenditure is a relevant factor in just what data are needed.

In a sense, a capital expenditure may call for a replacement decision, that is, an existing piece of equipment is to be replaced. For such a decision the information necessary would include:

- The investment and installation cost of the new piece of equipment

- The salvage value of the old machinery

- The economic life of the new equipment

- The operating cost of the new item over its life

Presumably, the economic decision would relate directly to the lower cost of production with the new piece of equipment, and possibly the opportunity to produce a greater quantity of output.

In contrast, consider an expansion type of decision. Assume a company wants to produce a new product to be sold in a new market. Then, not only must the economic data on the acquisition and operation of the new equipment be available, but also marketing information is required, such as estimates of:

- The market potential for the new product

- The probable sales quantity and value of the output for X years

- The marketing or distribution cost

Such a capital investment obviously will involve more risk than a replacement decision.

One other comment may be germane to securing good ideas and adequate information about new capital items. First, those who would use the equipment and are knowledgeable should be consulted. Too often management does not listen to this valuable source of information. Secondly, management should encourage the flow of ideas about capital expenditures, especially new processes and perhaps new products. It is far better to have too many good ideas than not enough. Ideas should be sought from many elements of the organization and compared. What is most desirable is a balanced agenda, rather than a limiting of ideas to any one department or single source.

As is discussed later, economic data on proposals normally should include all relevant cash flow information—cash outgo—the complete installation costs and operating expense, and cash inflow—the expected net sales revenues less related marketing expense, and so on. Any relevant economic data should be made available, such as tax data, inflation outlook, economic life of the project, other equipment needed, capacity data, cost information, and salvage value.

Here is an expanded list of the reasons that capital expenditures are made, all of which have a bearing on input data:

- To enable continued operation of the business

- To meet pollution control requirements

- To meet safety needs

- To reduce manufacturing or marketing (distribution) costs through more efficient use of labor, material, or overhead

- To improve the quality of the product

- To meet product delivery requirements

- To increase sales volume of existing or new products

- To diversify operations

- To expand overseas and so forth

METHODS OF EVALUATING PROJECTS

In an effort to invest funds wisely in capital projects, companies have developed several evaluation techniques. It is these expenditures that provide the foundation for the firm's growth, efficiency, and competitive strength. Because most companies do not have sufficient funds to undertake all projects, some means must be found to evaluate the alternate courses of action. Such decisions are not merely the application of a formula. The evaluation of quantitative information must be blended with good judgment, and perhaps good fortune, to produce that aggregate wisdom in capital expenditures that will largely determine the company's future earning power.

As will be seen, some entities have rather simple procedures while some of the more capital intensive managements feel a need for more sophisticated methods. Those companies using the more analytical tools find these three elements essential:

- An estimate of the expected capital outlay, as well as the amount and timing of the estimated future benefits—the cash flow

- A technique for relating the expected future benefits to a measure of cost—perhaps the cost of capital, or other “hurdle rates”

- A means of evaluating the risk—which relates to (a) the probability of attaining the estimated rate of return, and (b) a sense of how changes in the assumptions can affect the calculated return

The two more important valuation methods in use, which are quantitative in nature, consist of the following or some variation thereof:

- Payback method. This is the simple calculation of the number of years required for the proceeds of the project to recoup the original investment.

- Rate of return methods. Among them are:

- (a) The operators' method, so called because it is often used to measure operating efficiency in a plant or division. It may be defined as the relationship of annual cash return, plus depreciation, to the original investment.

- (b) The accountants' method, perhaps so named because the accounting concept of average book value and earnings (or book profit) is employed. This method is merely the relationship of profit after depreciation to average annual outstanding investment.

- (c) The investors' method or discounted cash flow method. This rate of return concept recognizes the time value of money. It involves a calculation of the present worth of a flow of funds.

PAYBACK METHOD

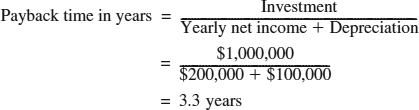

Assume that project A calls for an investment of $1,000,000 and that the average annual income before depreciation is expected to be $300,000. Then the payback in years would be 3.3 years, calculated thus:

In circumstances where the net income and depreciation are not approximately level each year, then the method may be refined to reflect cash flow each year to arrive at the payback time—instead of the average earnings. For example, assume an increasing stream of cash inflow followed by a decrease, then a matrix as in Exhibit 11.1, can be completed. In this illustration, the payback is completed in 5 1/2 years (5 years plus a $900,000/$1,800,000 fractional year).

Briefly stated, the payback method offers these four advantages:

- It may be useful in those instances where a business firm is on rather lean rations cashwise and must accept proposals that appear to promise a payback, for example, in two years or less.

- Payback can be helpful in appraising very risky investments where the threat of expropriation or capital wastage is high and difficult to predict. It weighs near-year earnings heavily.

- It is a simple manner of computation and easily understood.

- It may serve as a rough indicator of profitability to reject obviously undesirable proposals.

EXHIBIT 11.1 PAYBACK PERIOD—UNEVEN CASH FLOW

There are, however, three very basic disadvantages to the payback method:

- Failure to consider the earnings after the initial outlay has been recouped. Yet the cash flow after payback is the real factor in determining profitability. In effect, the method confuses recovery of capital with profitability. In the foregoing example, if the economic life of the project is only 3.3 years, there is zero profit. If on the other hand, the capital life is 10 years, the rate of return will differ significantly from that produced by a 4-year life.

- Undue emphasis on liquidity. Restriction of fund investment to short payback may cause rejection of a highly profitable source of earnings. Liquidity assumes importance only under conditions of tight money.

- Capital obsolescence or wastage is not recognized. The gradual loss of economic value is ignored—the economic life is not considered. This deficiency is closely related to item 1. Similarly, the usual (average) method of computation does not reflect irregularity in the earning pattern.

OPERATORS' METHOD

A manner of figuring return on investment, using the figures of the payback method, is:

The technique may be varied to include total required investment, including working capital.

The operators' method has these three advantages:

- It is simple to understand and calculate.

- In contrast with the payout method, it gives some weight to length of life and overall profitability.

- It facilitates comparison with other companies or divisions or projects, especially where the life spans are roughly comparable.

The basic disadvantage is that it does not recognize the time value of cash flow. Competing projects may have equal returns, but the distribution of earnings, plus depreciation, may vary significantly between them year by year and/or the total period over which equal annual returns are received may vary between projects.

ACCOUNTANTS' METHOD

This technique relates earnings to the average outstanding investment rather than the initial investment or assets employed. It is based on the underlying premise that capital recovered as depreciation is therefore available for use in other projects and should not be considered a charge against the original project.

There are variations in this method, also, in that the return may be figured before or after income tax, and differing depreciation bases may be employed.

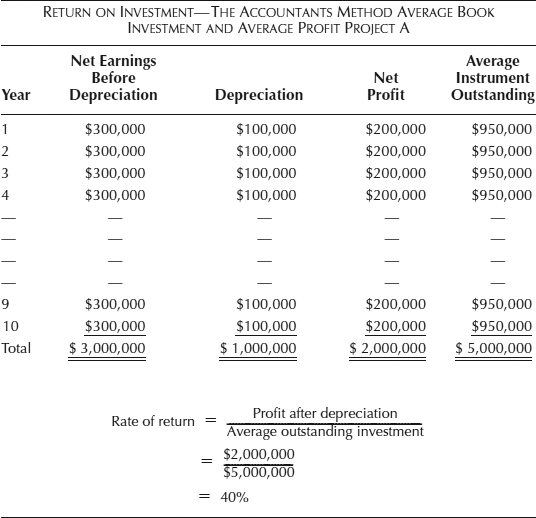

The rate of return using the accountants' method and assuming a 10-year life and straight-line depreciation on project A is shown in Exhibit 11.2.

EXHIBIT 11.2 RETURN ON INVESTMENT-THE ACCOUNTANTS METHOD

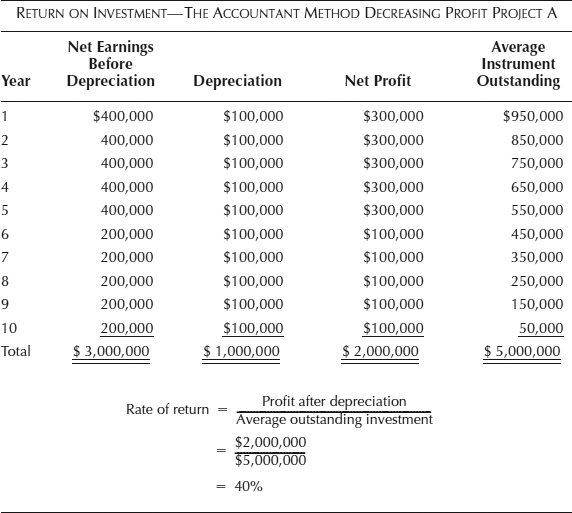

This basic procedure has two chief shortcomings. First, it is heavily influenced by the depreciation basis used. Double-declining balance depreciation will, of course, reduce the average investment outstanding and increase the rate of return. Second, it fails to reflect the time value of funds. In the example, if the average investment was the same but income was accelerated in the early years and decelerated in later years (with no change in total amount) the rate of return would be identical. Such conditions are reflected in Exhibit 11.3. By many measures, the cash flow shown in this illustration is more desirable than that reflected in Exhibit 11.2, because a greater share of the profit is secured earlier in the project life, and is thus available for other investment.

Most projects do vary in income pattern, and the evaluation procedure probably should reflect this difference.

The accountants' method offers the advantage of simplicity over the discounted cash flow approach.

DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW METHODS

Given the importance of capital expenditures to business, especially the capital intensive enterprises such as steel or chemicals, much thought has been directed to ways and means of comparing investment opportunities. It becomes very difficult to compare one project with another, particularly when the cash flow patterns vary or are quite different. When cash is received becomes very important in that cash receipts may be invested and earn something. The sooner the funds are in hand, the more quickly they can be put to work.

EXHIBIT 11.3 TRIAL AND ERROR—COMPUTATION OF INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN

Accordingly, the discounted cash flow principle has been adopted as a far superior tool in ranking and judging the profitability of the investments. The principle may be applied in two forms:

- The investors' method, also known as the internal rate of return (IRR)

- The net present value (NPV)

The first one actually involves the determination of what rate of return is estimated. The second method applies a predetermined rate, or hurdle, to the estimated stream of cash to ascertain the present value of the proposed investment.

Investors' Method: Internal Rate of Return

Technically, the rate of return on any project is that rate at which the sum of the stream of after-tax (cash) earnings, discounted yearly according to present worth, equals the cost of the project. Stating it another way, the rate of return is the maximum constant rate of return that a project could earn throughout the life of the outstanding investment and just break even.

The method may be simply described by an example. Assume that an investment of $1,000 may be made and, over a five-year period, cash flow of $250 may be secured. What is the rate of return? By a cut-and-try method, and the use of present value tables, we arrive at 8%. The application of the 8% factor to the cash flow results in a present value of approximately $1,000 is:

The proof of the computation is the determination of an 8% annual charge with the balance applicable to principal, just as bankers calculate rates of return.

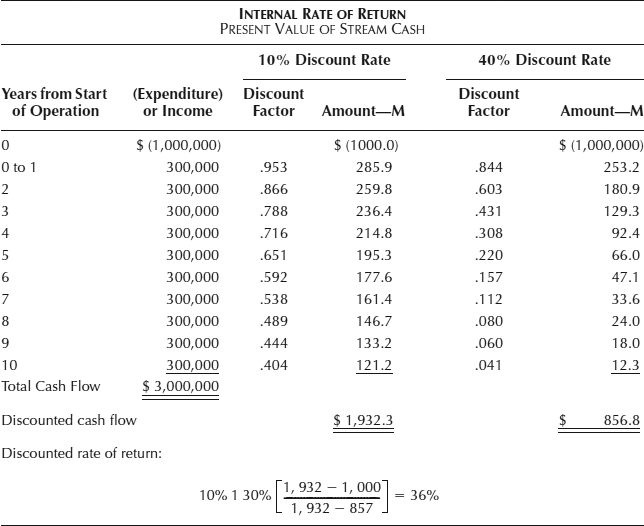

By trial and error, application of the proper discount factor can be explored until the proper one is found. Using a 10% discount factor and a 40% discount factor, the $1,000,000 assumed investment, discussed in connection with other evaluation methods, to be recouped over 10 years, results in a 36% rate of return, as shown in Exhibit 11.4.

The steps in application of the method may be described as:

- Determine the amount and year of the investment.

- Determine, by years, the cash flow after income taxes by reason of the investment.

- Extend such cash flow by two discount factors to arrive at present worth.

- Apply various discount factors until the calculation of one comes close to the original investment and interpolate, if necessary, to arrive at a more accurate figure.

The disadvantages of the discounted cash flow method are:

- It is somewhat more complex than other methods; this apparent handicap is minor in that those who must apply the technique grasp it rather readily after a couple of trials.

- It requires more time for calculation. However, the availability of handheld computers, or desktop computers, with a software package or built-in programs, makes the calculations rather painless.

- An implicit or inherent assumption is that reinvestment will be at the same rate as the calculated rate of return.

EXHIBIT 11.4 TRIAL AND ERROR—COMPUTATION OF INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN

These disadvantages are more than offset by the benefits. Among them are:

- Proper weighting is given to the time value of investments and cash flow.

- The use of cash flow minimizes the effect of arbitrary decisions about capital versus expenses, depreciation, and so on.

- Is comparable with the cost-of-capital concept.

- Is a valuable tool for the financial analyst in evaluating alternatives.

- Brings out explicit reasoning for selecting one project over another.

Net Present Value

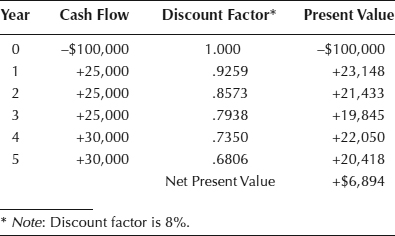

The typical capital investment is composed of a string of cash flows, both in and out, that will continue until the investment is eventually liquidated at some point in the future. These cash flows are comprised of many things: the initial payment for equipment, continuing maintenance costs, salvage value of the equipment when it is eventually sold, tax payments, receipts from product sold, and so on. The trouble is, since the cash flows are coming in and going out over a period of many years, how do we make them comparable for an analysis that is done in the present? By applying the discount rate to each anticipated cash flow, we can reduce and then add them together, which yields a single combined figure that represents the current value of the entire capital investment. This is known as its net present value.

For an example of how net present value works, we have listed in Exhibit 11.5 the cash flows, both in and out, for a capital investment that is expected to last for five years. The year is listed in the first column, the amount of the cash flow in the second column, and the discount rate in the third column. The final column multiplies the cash flow from the second column by the discount rate in the third column to yield the present value of each cash flow. The grand-total cash flow is listed in the lower right corner of the exhibit.

Notice that the discount factor in Exhibit 11.5 becomes progressively smaller in later years, since cash flows further in the future are worth less than those that will be received sooner. The discount factor is published in present value tables, which are listed in many accounting and finance textbooks. They are also a standard feature in midrange handheld calculators. Another variation is to use the following formula to manually compute a present value:

![]()

Using the above formula, if we expect to receive $75,000 in one year, and the discount rate is 15%, then the calculation is:

The example shown in Exhibit 11.5 was of the simplest possible kind. In reality, there are several additional factors to take into consideration. First, there may be multiple cash inflows and outflows in each period, rather than the single lump sum that was shown in the example. If a CFO wants to know precisely what is the cause of each cash flow, then it is best to add a line to the net present value calculation that clearly identifies the nature of each item, and discounts it separately from the other line items. An alternative way is to create a net present value table that leaves room for multiple cash flow line items while keeping the format down to a minimum size. Another issue is which items to include in the analysis and which to exclude. The basic rule of thumb is that it must be included if it impacts cash flow, and stays out if it does not. The most common cash flow line items to include in a net present value analysis are:

- Cash inflows from sales. If a capital investment results in added sales, then all gross margins attributable to that investment must be included in the analysis.

- Cash inflows and outflows for equipment purchases and sales. There should be a cash outflow when a product is purchased, as well as a cash inflow when the equipment is no longer needed and is sold off.

EXHIBIT 11.5 SIMPLIFIED NET PRESENT VALUE EXAMPLE

- Cash inflows and outflows for working capital. When a capital investment occurs, it normally involves the use of some additional inventory. If there are added sales, then there will probably be additional accounts receivable. In either case, these are additional investments that must be included in the analysis as cash outflows. Also, if the investment is ever terminated, then the inventory presumably will be sold off and the accounts receivable collected, so there should be line items in the analysis, located at the end of the project time line, showing the cash inflows from the liquidation of working capital.

- Cash outflows for maintenance. If there is production equipment involved, then there will be periodic maintenance needed to ensure that it runs properly. If there is a maintenance contract with a supplier that provides the servicing, then this too should be included in the analysis.

- Cash outflows for taxes. If there is a profit from new sales that are attributable to the capital investment, then the incremental income tax that can be traced to those incremental sales must be included in the analysis. Also, if there is a significant quantity of production equipment involved, the annual personal property taxes that can be traced to that equipment should also be included.

- Cash inflows for the tax effect of depreciation. Depreciation is an allowable tax deduction. Accordingly, the depreciation created by the purchase of capital equipment should be offset against the cash outflow caused by income taxes. Though depreciation is really just an accrual, it does have a net cash flow impact caused by a reduction in taxes, and so should be included in the net present value calculation.

The net present value approach is the best way to see if a proposed capital investment has a sufficient rate of return to justify the use of any required funds. Also, because it reveals the amount of cash created in excess of the corporate hurdle rate, it allows management to rank projects by the amount of cash they can potentially spin off, which is a good way to determine which projects to fund if there is not enough cash available to pay for an entire set of proposed investments.

HURDLE RATES

A hurdle rate is the minimum rate of return that a capital project should earn if it is to be judged acceptable. In reviewing this subject, on which there are a variety of opinions, perhaps these aspects are the more important ones:

- Value of using any hurdle rate

- Value of using a single hurdle rate

- Value of using multiple hurdle rates

Value of Hurdle Rates

Many companies do not establish hurdle rates, for a variety of alleged reasons, including:

- There is a large element of subjectivity in capital investments, and management wishes to review all proposals. It does not want to eliminate any from consideration simply because of the rate of return.

- When new business areas are to be considered, it is difficult to set a suitable hurdle rate.

- Many projects must be undertaken regardless of economic reasons: pollution abatement, safety equipment, and the like.

- If hurdle rates are used, then data will be manipulated so that the minimum profit rate will seem attainable.

If management wishes to maintain flexibility in its capital budgeting process, it seems this can still be done with proper instructions or guidelines, despite the existence of hurdle rates. Thus, provision can be made for some expenditures that do not relate directly to a given profit rate. Moreover, sound analytical procedures, including dismissal, can minimize any efforts to fabricate justification data. Additionally, if a for-profit business is an economic institution, and the authors think it is, and if the management task is to enhance shareholder value, then it seems guidelines must include profit rates which by and large do not dilute the shareholder's equity.

A Single Hurdle Rate?

A great many companies that employ the hurdle rate concept use a single rate, as distinguished from different rates for various kinds of expenditures. The reasoning in the application of one hurdle rate is basically this:

- The cost of capital, a good point of departure, is about the same for all segments of the company (divisions, subsidiaries, product lines, etc.).

- The additional risk in attempting to earn an acceptable return on equity is essentially the same for all parts of the company.

- Given the elements of error in estimating the rate of return on the capital project, the future cost of capital, and the subjective nature of the decision, it isn't worth the effort to establish several hurdle rates.

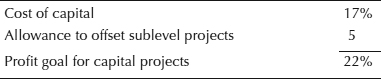

One of the common single hurdle rates employed is closely associated with the cost of capital, discussed in the next section. Some projects do not earn the cost of capital, so a factor must be added as the goal of other projects so that, on average, the proper earnings level is maintained.

A single hurdle rate might be established thus:

COST OF CAPITAL—A HURDLE RATE

Technically, the cost of capital is the rate of return the long-term debt holders and shareholders require to persuade them to furnish the required capital. Thus, assume that:

- A company capital structure target objective is $500,000,000 composed of 25% debt and 75% equity.

- In the current market environment long-term bondholders require a 10% return (6% cost to the company after income taxes); a 17% return on equity is the going earnings rate.

Then the cost of capital would be calculated as:

It could be argued that if the company is to attract the capital required to stay in business, then, on average, all its capital investments should earn at least 14% after taxes. If this does not occur, then the shareholder return would be diluted. Of course, it would be well to consult with the investment bankers as to the bondholder and shareholder expectations on earnings of the company and industry for the next several years. Depending on their views, a cost of future capital might be determined based on the relation of expected earnings to expected market value of the stock, plus the yield the bondholders might require. In this manner, the minimum return for capital projects could be estimated.

This calculation represents the average cost of capital and seems a fair basis for capital investment decisions viewed on the thesis that the true cost of capital is calculated on a pool basis. However, there might be some circumstances where the marginal or incremental cost of capital basis may be calculated for informational use. This is the cost of capital for the most recent capital transaction considered, such as the opportunity cost of not repurchasing common stock, or of not repaying debt. However, this application would be viewed as the cost of a specific source of capital. It seems to the authors that the pool concept of capital is the more appropriate basis for evaluating capital expenditures.

In any event, cost of capital, or cost of capital adjusted for some subnormal rates of return on some projects, might be a suitable hurdle rate.

Multiple Hurdle Rates

In these days of multinational companies, and conglomerates operating in many business sectors, a case could be made for using multiple hurdle rates. The use of multiple hurdle rates could be justified for different segments of a business where:

- Different business risk exists (threat of expropriation, adverse business environment, etc.).

- Rates of return expectations are markedly different (as in some non-U.S. geographical areas).

- Experienced earnings rates are much different.

- Differing business strategies may apply and require different hurdle rates for a time.

However, whether different hurdle rates should be determined, or whether management should make mental adjustments to a single hurdle rate, depends on management inclinations. Intuitive judgment still plays an important role in capital expenditure decisions.

INFLATION

Those involved in analyzing capital investments may ponder how inflation should be handled. Even so-called “modest” inflation rates of 5% or 6% can significantly influence results. In the budgetary process, these questions should be considered:

- Should adjustments be made for inflation in the cash flows?

- Should one inflation rate be applied to the entire period, or should year-to-date adjustments be made?

- If available, should specific estimated inflation rates be used on each factor (i.e., wages, material costs, product prices)?

- Should the hurdle rate be adjusted to provide for inflation?

Four comments on these questions are:

- Many companies do not adjust for inflation. The reasons for not recognizing inflation range from the pragmatic—that product prices and revenues changes probably will at least match cost movements—to the recognition of the difficulty in getting a reliable rate estimate.

However, those more analytical souls, and those using DCF techniques and the computer, are more likely to adjust for inflation.

- Many analysts engaged in long-range planning use an average inflation rate because of the difficulty of getting more realistic data. However, if estimates of inflation by near-term years are available, perhaps these should be used, with an average “guess” for the later years.

- Specific price indices exist for some materials, or groups of materials, and for wages in particular industries.

With the availability of computers, if the company believes there will be wide variations of inflation in segments of the business, it might be well to test the results of applying specific inflation indexes.

- If cash flows are adjusted for inflation, then the hurdle rate also probably should be adjusted for estimated inflation. However, if constant dollars are used in projections, then obviously the hurdle rate should not be adjusted for estimated inflation.

In reaching conclusions on any of these points the analysts probably should secure estimates of inflation, and experiment on the computer with the impact on the answer.

FOREIGN INVESTMENTS

Investments by the multinationals in countries with hyperinflation rates must separately consider the effect of these conditions on the real rate of return—and the desirability of making any capital investments at all.

When a discounted cash flow method (or, indeed, any method) is used to evaluate investments in another country, it is to be emphasized that the significant test is the cash flow to the parent—not to the foreign subsidiary or entity. Among the impediments to cash flow to the parent, which must be considered (for each year) and factored into the decision, are such items as:

- Currency restrictions

- Fluctuations in the foreign exchange rate

- Political risk

- Withholding taxes

- Inflation (as mentioned)

Limited discussion of these topics is contained in Chapter 10.

IMPACT OF THE NEW MANUFACTURING ENVIRONMENT

Investments are made in capital assets with the expectation that the return will be sufficiently high not only to recoup the cost but also to pass the hurdle rate for such an expenditure. But the nature of the investment is changing, as are the attendant risks, in the new manufacturing environment.

The nature of this net setting is reflected in these characteristics:

- While automation is viewed as a primary source of additional income, this often is preceded by redesigning and simplifying the manufacturing process, before automation is considered. Many companies have achieved significant savings simply by rearranging the plant floor, establishing more streamlined procedures, and eliminating the non-value-adding functions such as material storage and handling. After this rearrangement is accomplished, then automation might be considered.

- Investments are becoming more significant in themselves. While a stand-alone grinder may cost $1 million, an automated factory can cost $50 million or $100 million. Moreover, much of the cost may be in engineering, software development, and implementation.

- The equipment involved often is more complex than formerly, and the benefits can be more indirect and perhaps more intangible. If there are basic improvements in quality, in delivery schedules, and in customer satisfaction (which seems to be the emphasis today), then methods can be found to measure these benefits. (These gains may lie in improvements or lower costs in the support functions—such as purchasing, inventory control, and greater sales volume.)

- Because of the high investment cost, the period required to earn the desired return on investment is longer. This longer-term horizon, together with the intangibles to be considered and the greater uncertainty, require the controller, budget officer, or management accountant to be more discerning in his evaluation. Usually the indirect savings and intangible benefits need to be recognized and included in the investment analysis. (The direct benefits may be insufficient to justify the investment.)

IMPACT OF ACTIVITY-BASED COSTING

One output of the cost system may be used to determine the real net cash flow from the capital investment—and that is the sales revenues less the variable costs or direct cash costs of the specific products to be manufactured. Often, the allocation methods and the depreciation system do not reflect the realities of the manufacturing process. Hence, the relevant cost of sales may be substantially incorrect, leading to an improper cash flow calculation. Alternatively, the technology costs related to the product may be in error and, the larger the technology costs, the greater the impact of misallocation of product costs. Accordingly, the controller as well as the financial analyst developing, or reviewing, the capital investment justification should ascertain that the costing system accurately mirrors the resources needed in the relevant decision.

CLASSIFYING AND RANKING PROPOSED CAPITAL PROJECTS

When the reviews and analyses have been completed, it is necessary to bring order out of chaos, and to classify and rank the projects in some order of priority for discussion purposes. This is a necessary procedure because usually there are many more proposed capital expenditures than would normally be undertaken within the bounds of financial capability. Projects are ranked for discussion with top management (and the board of directors) on the basis of perceived need. While profitability may be a ranking factor for some categories, it does not follow that it is the only basis.

A practical grouping that would be understood by management and operation executives alike might be in some such order as:

- Absolutely essential:

- (a) Installation of equipment required by government agencies, such as:

- (i) Safety devices

- (ii) Pollution abatement vehicles without which the business would be shut down

- (b) Replacement of inoperable facilities without which the company could not remain in business

- (a) Installation of equipment required by government agencies, such as:

- Highly necessary:

- (a) State-of-the-art quality control devices

- (b) New flame-retardant painting facilities

- (c) High-intensity laser drills

- Economically justified projects:

- (a) New facilities in Vancouver, British Columbia

- (b) Robot assembly line for casings

- (c) Warehouse in Denver, Colorado

- All other:

- (a) Community center in Delaware, Maryland (public relations)

- (b) New lighting facilities in parking area (two shifts will be starting)

- (c) Outdoor cafeteria facilities for employees

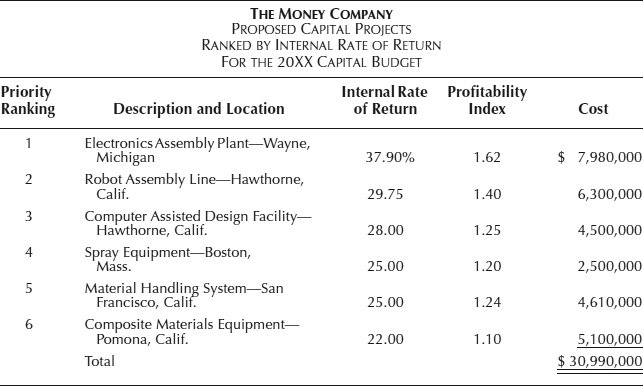

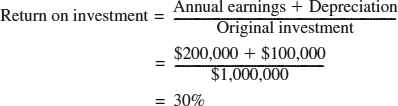

For projects based on the economic return, usually these projects may be ranked by rate of return. An example is shown in Exhibit 11.6. It will be noted that a profitability index also is provided. As explained under the “mutually exclusive projects” section, on some occasions the proposal with the highest rate of return may not be the one with the highest profitability index.

While a ranked list of economically desirable projects may be provided, which keeps the total capital budget request within the guideline amount, sometimes a “contingent capital budget project” listing also is prepared in the event management or the board of directors decides to appropriate more funds than originally contemplated. These projects would rank just below the formal proposals as to rates of return.

EXHIBIT 11.6 PROPOSED CAPITAL PROJECTS BY ECONOMIC RANKING

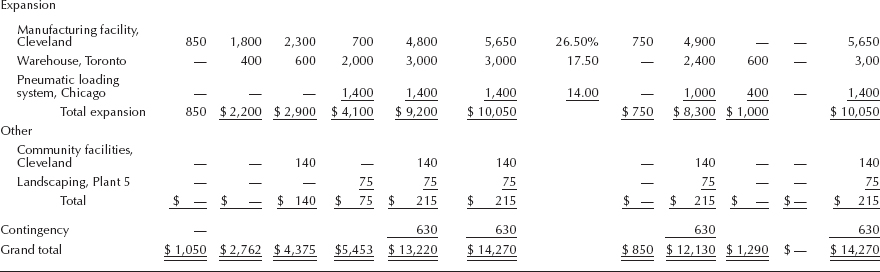

BOARD OF DIRECTORS' APPROVAL

Under normal circumstances, when management has decided what capital budget projects should be undertaken and be included in the annual business plan, approval of the board of directors is sought. Usually either the chief operating officer of the vice president in charge of facilities makes the presentation, perhaps with a visual aid much like that shown in Exhibit 11.7. The data are presented in some logical form and display the significant facts. The objective is to make the board aware of the reason for, benefits of, and risks attached to, each project. The information included in the proposal as reflected in Exhibit 11.7 contains:

- An identification of each project

- The priority and category of each project

- The reason for the proposed item

- The total anticipated cost

- The rate of return (where this is the basis of selection)

- The timing of the expenditures

- A contingency fund in the event of cost overruns

Any cost estimates, the rate of return, and availability of funds, and so forth should be checked, or calculated, by the controller's office before submission to the board (or management).

In securing the approval of the board of directors, there is one other aspect that often should be brought to the attention of the board and that has to do with GAAP.

EXHIBIT 11.7 ANNUAL CAPITAL BUDGET REQUEST

Impact of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

Just as the discussion of activity-based costing (ABC) has stimulated management accountants to recheck the cost drivers and allocation methods of the cost systems used in their companies, so also recent articles about the tendency of GAAP applications to discourage needed investment in new equipment such as computer integrated technology, is causing some thought about the accounting methodology in use in certain circumstances. Some of the alleged difficulty arises because of the practice of expensing, and not capitalizing, the startup costs of the new project, or perhaps the tendency to focus on short-term earnings, or the failure to recognize life-cycle accounting. The impact of a capital expenditure on earnings may cause the small company to reflect a loss in the initial years after the investment, even though the ultimate rate of return is excellent. Allegedly, a prospective loss might deter some banks from making a loan. (A diligent bank will carefully examine the cause of any expected loss.) This brings us to a consideration of what information should be provided to the board of directors and top management about the impact of new product development or major capital expenditures on the earnings of the company. It has nothing to do directly with the rate of return or project justification; these are separate considerations. It does relate to making the decision makers aware of the profit impact of capital investments and the related costs.

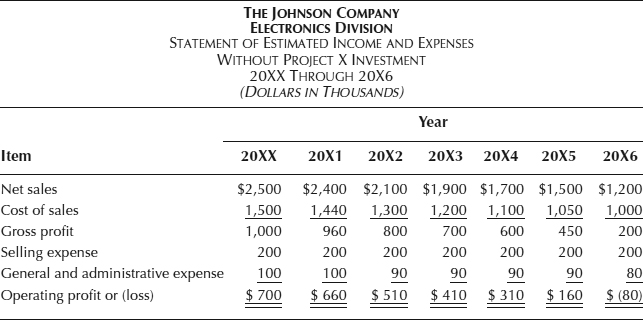

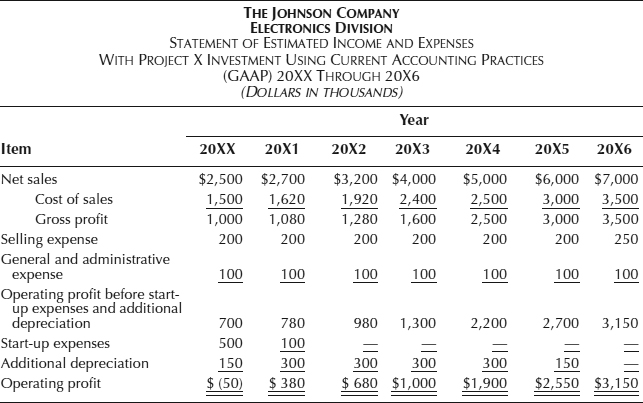

Perhaps these three supplemental forecast earnings statements may be useful to an informed management when considering any major expenditure (as well as for the purpose of obtaining necessary financing):

- A statement of estimated income and expense without the new investment—for a number of years in the future

- A statement of estimated income and expense, with the new investment, using GAAP (with emphasis on startup expenses and depreciation)—if that is a point to emphasize

- A statement of estimated income and expense, with the new investment, with a modified or alternative capitalization and depreciation practice.

These are illustrated in Exhibits 11.8 through 11.10.

Exhibit 11.8 shows the anticipated decline in the operating profit of the Electronics Division without the investment under consideration (new manufacturing equipment also having additional capacity).

EXHIBIT 11.8 STATEMENT OF ESTIMATED INCOME AND EXPENSE WITHOUT PROJECT X INVESTMENT

EXHIBIT 11.9 STATEMENT OF ESTIMATED INCOME AND EXPENSE WITH PROJECT X INVESTMENT USING CURRENT ACCOUNTING PRACTICES (GAAP)

EXHIBIT 11.10 STATEMENT OF ESTIMATED INCOME AND EXPENSE WITH PROJECT X INVESTMENT AND WITH MODIFIED ACCOUNTING PRACTICES

Exhibit 11.9 reflects the tremendous increase in operating profit, after the first two years, by making the investment in Project X. It also shows the effect of the write-off, in the years of incurrence of the startup costs, and the depreciation of the capital asset cost of $1,500,000 over a five-year life (straight line depreciation, with a one-half year of depreciation in 20XX). The use of a generally accepted accounting practice involving immediate write-off of startup costs in the years of occurrence, and commencement as early as possible of depreciation charges on a straight line five-year basis (not on a per unit of output), causes an operating loss in 20XX and a severe reduction in operating profit in 20X1.

Exhibit 11.10 shows the impact of a less conservative accounting practice—the immediate capitalization of the startup costs, with the subsequent amortization of the charge over a two-year period of operation, and the deferment of immediate depreciation of the capital assets, also for a two-year period, and a subsequent write-off over a five-year period. Such a practice avoids an operating loss in the first year of operations and avoids a large reduction in the operating profit of the second year of operation—with the heavier additional costs being deferred until there is a significant pickup in sales and operating profit (before such additional charges).

Providing such data to the board of directors advises them of the impact on expected operating profit of the proposed investment on two different accounting bases. This information would be in addition to that listed earlier. It rounds out the financial picture and perhaps avoids later questions. The annual plan and strategic plan should incorporate the effect of the expenditures on the statement of income and expense, the statement of financial position, and the statement of cash flows. This same data should be made available to the commercial banks, or other financial sources, who are asked to provide the financing. The authors suggest full disclosure of the financial statements of the annual plan and long-range plan to the financing institution, including the schedule for complete payment of the obligation.

When and if the board approves the project, the cognizant officer is notified. This constitutes an approval in principle. Specific project approval, as discussed in the next section, is required before the project may proceed.

PROJECT AUTHORIZATION

Under most circumstances, the analysis and review done in connection with securing project approval by the board of directors should be sufficient to complete a detailed authorization request. However, circumstances do change, and a period of six months might pass between the gathering and analysis of data for the board review. So sometimes this re-review is worthwhile. Also, it causes the project sponsors to commit in writing to the project. An illustrative form is shown in Exhibit 11.11.

It should be mentioned that authority required to commence a project depends on the amount of the request. While approval of the president for all projects might be needed in a small firm, in larger ones there might be an ascending scale of required approvals, perhaps as:

| Amount | Required Approval |

| Less than $10,000 | Plant Manager |

| $10,000–99,999 | General Manager |

| $100,000–499,999 | Chief Operating Officer |

| Over $500,000 | Chief Executive Officer |

The sample form provides for comments and recommendations by the controller as well as the line approval (depending on the amount).

EXHIBIT 11.11 REQUEST FOR EQUIPMENT AND FACILITY AUTHORIZATION

ACCOUNTING CONTROL OF THE PROJECT

When the work authorization has been properly approved, then the task of the controller is to keep tabs on both commitments and expenditures as well as expected costs to complete the project, and periodically report the data to the cognizant executive. Typically these figures are reported by project or work order:

- Amount authorized

- Actual commitments to date

- Actual costs incurred to date

- Estimated cost to complete

- Indicated total cost

- Indicated overrun or underrun compared to the project budget

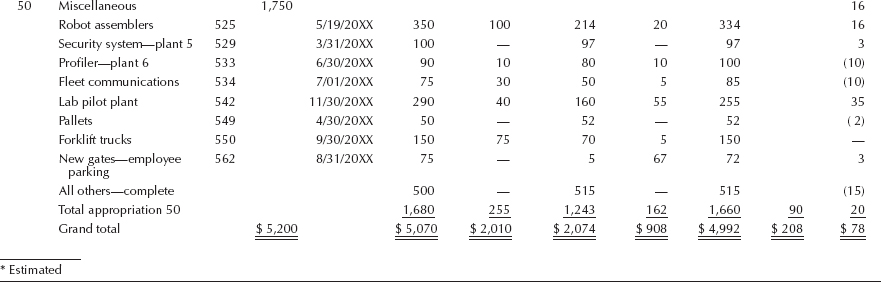

An illustrated report, prepared monthly and in which control is by appropriation number, is shown in Exhibit 11.12.

For large and complicated projects a computer application may be appropriate.

POSTPROJECT APPRAISALS OR AUDITS

In many companies adequate analyses are made as to the apparent economic desirability of a project, and acquisition costs are held within estimate. Yet the project may not achieve the estimated rate of return. A sad truth is that some managements are unaware of such a condition because there is no follow-up on performance.

For large projects, especially, after a limited or reasonable period beyond completion—perhaps two years on a very large capital investment—when all the “bugs” are worked out, it is suggested that a postaudit be made. The review might be undertaken by the internal audit group, or perhaps a management team consisting of line managers involved with the project (but not among the original justification group) and some members of the controller's staff. The objective, of course, is to compare actual earnings or savings with the plan, ascertain why the deviation occurred, and what steps should be taken to improve capital investment planning and control. The scope might range from the strategic planning aspects (should the company be in the business?) through to the detailed control procedures.

The following advantages may accrue from an intelligently planned postaudit:

- It may detect weaknesses in strategic planning that lead to poor decisions, which in turn impact the capital budget procedures.

- Environmental factors that influence the business but were not recognized might be detected.

- Experience can focus attention on basic weaknesses in overall plans, policies, or procedures as related to capital expenditures.

- Strengths or weaknesses in individual performance can be detected and corrected—such as a tendency to have overly optimistic estimates.

- It may enable corrections in other current projects prior to completion of commitments or expenditures.

- It affords a training opportunity for the operating and planning staff through the review of the entire capital budgeting procedure.

- Prior knowledge of the follow-up encourages reasonable caution in making projections or preparing the justification.

- It may detect evidence of manufactured input data.

EXHIBIT 11.12 CAPITAL APPROPRIATIONS AND EXPENDITURES

EXHIBIT 11.13 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE REPORT

The scope and postcompletion period of the review will depend on circumstances. Some companies limit the audit only to major projects over $1 million and only until the payback period is completed.

A simple form of graphic report quickly summarizing actual and expected performance is illustrated in Exhibit 11.13. The postaudit report commentary, of course, can touch on estimated cash flow to date of the audit as compared with actual cash flow, old versus new break-even points, and operating expenses, planned versus actual, as well as other pertinent observations.

OTHER ASPECTS OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURES

Working Capital

This chapter, up to this point, has dealt with capital expenditures in the strictest sense. In many cases this is proper in that, when a capital expenditure other than cash outflow is made, there is no impact on working capital. Yet, many instances, such as growth or expansion in the business, will require additional investment in inventory and receivables as well as the plant and equipment needs. Suffice it to say that if additional working capital is necessary, then it should be reflected in the investment requirement and in the rate of return calculation. It is partially offset by the salvage value recovery when the business ceases.

Lease versus Buy Decisions

Technically speaking, the acquisition of a long-term asset, whether purchased or leased, should be included in the capital budget. However, the rental of the asset or leasing it on a short-term basis would not warrant this treatment.

The discounted cash flow technique may be useful in reaching a decision whether to lease or buy, and several good reference sources are available on the subject. The best method to be used is either IRR or NPV, and treatment of some of the variables is controversial. The authors suggest the NPV method is perhaps easy to apply. If the marginal financing (net of taxes) cost of funds to purchase the asset is known, the same discount rate can be applied to the stream of lease payments to arrive at the net present value. Usually the alternative with the lower NPV, and the higher savings, should be the one selected. The comparative net present values of lease vs. purchase (with no investment tax credit) are shown in Exhibit 11.14. This application assumes a 15% interest borrowing rate, less a 40% tax rate, or a net cost of 9%. The net savings through purchase may be calculated as:

| Present value of purchase | $ 1,000,000 |

| Less: Present value of related tax savings | 311,120 |

| Net purchase cost | $ 688,880 |

| Savings (NPV) by purchase over lease | |

| Present value of lease cost | $ 733,632 |

| Net purchase cost (above) | 688,880 |

| Net savings | $ 44,752 |

Mutually Exclusive Capital Proposals

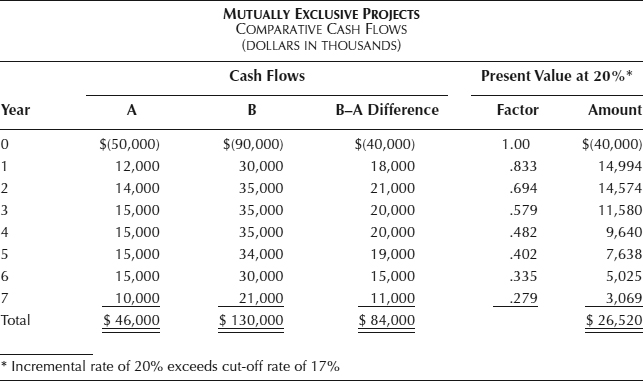

In the capital budgeting process there may be instances when the estimated rate of return on any two projects is the same, but funds are available for only one. The two projects, by definition, are mutually exclusive. How should a decision be made as to which proposal to accept? One complicating factor is that the IRR method may rank projects somewhat differently than the NPV approach. Such a condition can arise because the IRR method assumes that funds generated are reinvested at the discounted rate calculated for the initial investment. The NPV method assumes funds are reinvested at the rate used for discounting, which is often the cost of capital. Other reasons for differing evaluations relate to different project lines and different initial investments. When the projects are mutually exclusive, one way of making a decision is to (1) calculate the differences in cash flow, and (2) apply the opportunity cost rate, or cost of capital rate, to these cash flow differences.

Assuming the incremental or opportunity cost rate is higher than the capital budget cut-off rate, then the proposal with the higher value should be selected. As reflected in Exhibit 11.15, Project B should be accepted.

Plant and Equipment Records

Adequate plant and equipment records are a necessary adjunct to effective control. They provide a convenient source of information for planning and control purposes as well as for insurance and tax purposes. Some of the advantages may be enumerated as:

- Provide necessary detailed information about the original cost (and depreciation reserves) of fixed assets by type of equipment or location.

EXHIBIT 11.14 NPV CALCULATION—LEASE VERSUS BUY

- Make available comparative data for purchase of new equipment or replacements.

- Provide basic information to determine proper depreciation charges by department or cost center and serve as a basis for the distribution of other fixed charges such as property taxes and insurance.

- Establish the basis for property accountability.

- Provide detailed information on assets and depreciation for income tax purposes.

- Are a source of basic information in checking claims and supporting the company position relative to personal and real property tax returns?

EXHIBIT 11.15 INCREMENTAL INVESTMENT—MUTUALLY EXCLUSIVE PROJECTS

- Serve as evidence and a source of information for insurance coverage and claims.

- Provide the basis for determining gain or loss on the disposition of fixed assets.

- Provide basic data for control reports by individual units of equipment.

Property records include the plant ledgers and detailed equipment cards. The ledgers will follow the basic property classifications of the company. Detailed records must be designed to suit the individual needs of the company. Information in a data bank, preferably stored in a computer, should include:

- Name of asset

- Type of equipment

- Control number

- Description

- Size

- Model

- Style

- Serial number

- Motor number

- Purchased new or used

- Date purchased

- Vendor

- Invoice number

- Purchase order number

- Location

- Plant

- Building

- Floor

- Department

- Account number

- Transfer information

- Original cost information

- Purchase cost

- Freight

- Tax

- Installation cost

- Material

- Labor

- Overhead

- Additions to

- Date retired

- Sold to

- Scrapped

- Cost recovered

- Depreciation data

- Estimated life

- Annual depreciation

- Basis

Additional information may be required in particular companies. However, a database should be complete so that appropriate reports can be prepared.

There are numerous software packages available that permit the generation of most conceivable needs as regards reports or fixed assets.

Internal Control and Accounting Requirements

Once the property has been acquired, the matter of proper accounting and control arises. Usually, such duties become the responsibility of the controller. The problem is essentially very simple, but a few suggestions may prove helpful:

- All fixed assets should be identified, preferably at the time of receipt; a serial number may be assigned and should be affixed to the item. Use of metal tags or electrical engraving is a common method of marking the equipment.

- Machinery and equipment assigned to a particular department should not be transferred without the written approval of the department head responsible for the physical control of the property. This procedure is essential to know the location for insurance purposes and to correctly charge depreciation, etc.

- No item of equipment should be permitted to leave the plant without a property pass signed by the proper authority.

- Periodically, a physical inventory should be taken of all fixed assets.

- Detailed records should be maintained on each piece of equipment or similar groups.

- Purchase requisitions and requests for appropriations should be reviewed to assure that piecemeal acquisitions are not made to avoid the approval of higher authority. Thus if all expenditures over $100 require the signature of the general manager, individual requisitions may be submitted for each table or each chair to avoid securing such approval.

- Retirement of fixed assets by sale or scrapping should require certain approvals to guard against the disposal of equipment that could be used in other departments.

- If possible, bids should be secured on any sizable acquisitions.

- Provision should be made for proper insurance coverage during construction as well as on completion.

- Expenses should be carefully checked to decrease the possibility that portions of capital expenditures are treated as expenses to avoid budget overruns.

Idle Equipment

Another phase of control over fixed assets relates to unused facilities, whether only of short duration or for more extended periods. In every business, it can reasonably be expected that some loss will be sustained because of idle facilities and/or idle workers. The objective is to inform management of these losses and place responsibility in an attempt to eliminate the avoidable and unnecessary costs. But aside from stimulating action to eliminate the causes of short-term idleness, such information may be a guide in determining whether additional facilities are necessary. Also, such knowledge may encourage disposal of any permanently excess equipment, giving consideration to the medium-term plans.

Losses resulting from unused plant facilities are not limited to the fixed charges of depreciation, property taxes, and insurance. Very often idle equipment also results in lost labor, power, and light, as well as other continuing overhead expenses, to say nothing of startup time and lost income from lost sales.

Causes of idle time may be threefold:

- Those controllable by the production staff. These may result from:

- (a) Poor planning by the foreperson or other production department staff member

- (b) Lack of material

- (c) Lack of tools or other equipment

- (d) Lack of power

- (e) Machine breakdown

- (f) Improper supervision or instructions, etc.

- Those resulting from administrative decisions. For example, a decision to build an addition may force the temporary shutdown of other facilities. Again, management may decide to add equipment for later use. Here certain idle plant costs may be incurred until the expected demand develops.

- Those arising from economic causes. Included are the causes beyond the control of management, such as cyclical or seasonal demand. In somewhat the same class is idle time resulting from excess capacity in the industry. The effect of such conditions may be partially offset by efficient sales planning and aggressive sales effort.

The cause of idle time is important in determining the proper accounting treatment. Where idle facilities result from economic causes or are otherwise highly abnormal—such as a prolonged strike—it may be desirable for the controller to have such costs segregated and handled as a separate charge in the statement of income and expense. Such expenses should not be included in inventory or cost of sales.

Some companies isolate in the manufacturing expenses the cost of idle time that is controllable by the production staff. In other cases, a simple reporting of the hours is all that is necessary. Where it is desirable to charge the costs of idle time to a separate account the segregation is simple through a comparison of normal and actual hours and the use of standard rates.

Depreciation Accounting

Depreciation has been defined in many ways, such as a dictionary definition, “decline in value of an asset due to such causes as wear and tear, action of the elements, obsolescence and inadequacy.” The accounting profession has considered several definition, and after long consideration the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Committee on Terminology formulated the following definition:

Depreciation accounting is a system of accounting which aims to distribute the cost or other basic value of tangible capital assets, less salvage (if any), over the estimated useful life of the unit (which may be a group of assets) in a systematic and rational manner. It is a process of allocation, not of valuation. Depreciation for the year is the portion of the total charge under such a system that is allocated to the year. Although the allocation may properly take into account occurrences during the year, it is not intended to be a measurement of the effect of all such occurrences.1

In arriving at the applicable charges for depreciation, there are at least three related objectives of proper accounting: (1) to state earnings correctly; (2) to protect the investment of owners and creditors by maintaining the integrity of the fixed capital accounts (a write-off of plant and equipment over the useful life, by charges against income, tends to avoid the payment of dividends out of capital); and (3) to secure useful costs through proper depreciation allocations to cost centers. Another objective might be to maximize tax deductions (depreciation) under the applicable IRS code.

The accomplishment of these objectives must lie largely in the controller's hands. The determination of the useful life of the plant and equipment is largely an engineering problem. However, the ramifications and implications of depreciation policy—such matters as treatment of obsolescence, accounting for retirements, determination of allocation methods, and selection of individual or group rates—are best understood by the accountant. For these reasons, the controller should be the primary force in recommending to management, as may be necessary, the policies to be followed.

Obsolescence

Obsolescence, sometimes called functional depreciation as distinguished from physical depreciation, can be a highly significant factor in determining useful economic life. More often than not, the usefulness of facilities is likely to be limited by obsolescence, so that it may outweigh the depreciation factor. Such a condition can occur as a result of two causes. The product manufactured may be replaced by another, so that the need no longer exists for the facility. Or a new type of asset—one that produces at a much lower cost—may be developed to supersede present manufacturing equipment. Sometimes the need for expanded capacity has the effect of rendering obsolete or inadequate the existing asset.

Obsolescence may be of two kinds—normal or special. The former is the normal loss in value and can be anticipated in the same degree as other depreciation factors. It should be included in the estimate of useful life. Extraordinary or special obsolescence, on the other hand, can rarely be foreseen. The controller's responsibility generally should extend to a review of past experience and trends to determine whether obsolescence is an important consideration in his industry. If so, then it should be duly recognized in the useful life estimates.

In accounting for obsolescence, the question must be settled about whether a distinction should be made in the accounts between charges for obsolescence and depreciation. In practice, the normal obsolescence will be combined with depreciation in both the provision and the reserve. A highly abnormal and significant obsolescence loss probably should be segregated in the income and expense statement. Aside from this, circumstances may indicate the desirability of segregating a reserve for obsolescence. It may not be possible to identify obsolescence with a particular asset, although experience will indicate the approximate amount. This can be handled as a general provision without regard to the individual piece of equipment.

Fully Depreciated Assets

In properly stating on the balance sheet the value of fixed assets and in making the proper charge to manufacturing costs for the use of the plant and equipment, the question is raised about the correct accounting treatment of fully depreciated assets. If the facilities are no longer of use, they should be retired and the amount removed from both the asset and the reserve. If the item is fully depreciated but still in use, then the depreciation charge to the earnings statement must be discontinued—unless a composite useful life estimate or a composite depreciation rate is being used. The controller should consider these conditions, as well as increased maintenance costs, in evaluating operating performance and in preparing useful reports for management.

Appraisals and Appraisal Records

Management may request appraisals of property for any one of several reasons: for the purchase or sale of property, for reorganization or liquidations, for financing when the property is collateral, for insurance purposes, for taxation purposes, and for control purposes when the records do not indicate investment by process or cost center.

The basis of valuing fixed assets has already been reviewed, and the desirability of stating such property at original cost has been emphasized. However, occasions arise when management directs the valuation of property on another basis, perhaps to remove extremely high depreciation charges. When appraisals are recorded, the original cost and depreciation on original cost should continue to be reflected in the detail records, along with the appraised value and depreciation thereon.

Loss or Gain on the Sale of Fixed Assets

The matter of accounting for the loss or gain on the sale or other disposition of fixed assets is primarily one of accounting theory. Some have supported the proposition that losses resulting from premature retirement or technological advances are properly capitalized and charged against future operations. Most authorities do not concur in this view. The sound value—or asset value, less accumulated depreciation—for all assets retired is a loss that should be charged off as incurred. It is in the nature of a correction of prior profits. Usual practice is to carry such gain or loss, if important, in the nonoperating section of the statement of income and expense.

Funds for Plant Replacement and Expansion

Unfortunately, a great deal of confusion has arisen among laymen about the distinction between a reserve and a fund. Some think that the creation of a depreciation reserve also establishes a fund to replace the property. Accountants know that a reserve may exist independent of a fund and that a fund can exist without a reserve. The depreciation reserve does not represent a fund of cash or other assets that have been set aside. It only expresses the usage of the asset. If the operation has been profitable, and if dividends have not been paid in excess of the net income after recognizing depreciation, then values of some sort are available to offset the charge for use of the plant and equipment.

Most companies do not establish funds for property expansion or replacement but use the general funds instead. However, such funds can be created, and some exponents believe that public utilities and wasting asset industries, such as mining, should establish such funds. Such funds are not necessarily to be measured by the depreciation reserve, because replacement costs may be quite different. The depreciation reserve is a measure of expired past value, not future requirements for replacement.

Plant and Equipment in Relation to Taxes

Many local communities and states levy real and personal property taxes or enforce payment of franchise taxes based on property values. Maintenance of adequate records can be a means of satisfying the taxing authorities on problems of valuation.