This chapter turns the focus of attention to the program manager, where we comprehensively describe his or her primary roles and responsibilities. Numerous times in this book we have described programs as business vehicles to make money and achieve other strategic objectives and program managers as business leaders who are in charge of the vehicles.

The fact that we see program managers as business leaders portrays them as a special type of mover and shaker. And, they really are! Program managers make or break the business side of their programs, managing finances, monitoring the market, and battling business risks. In that way, their programs add to or take away from the value proposition to the company's portfolio of programs and improve or worsen the company's bottom line.

We present the subject matter through several steps. First, we show that the job of a business unit GM is to invest money to realize a set of business objectives and use program managers to accomplish that. We then describe the business responsibility of program managers in managing the investment. For simplicity, we split the responsibility into two groups: managing the business and leading the program team. This chapter seeks to help all members of an organization who are involved with a program understand the following:

The role of the program manager is that of a business manager who performs the business function for his or her specific program

How the program manager manages all aspects of the business on a program

How the program manager manages the program business by leading a team of qualified functional specialists

Developing program managers who function as business leaders within an organization may be a significant paradigm shift for some organizations. However, it may be that this paradigm shift is needed to take a company further down the road of success.

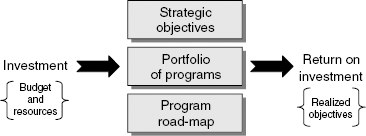

Companies survive by generating enough income to pay for their operating expenses. Companies grow by investing a portion of their income in vehicles that generate more revenue and decrease operating expenses. Companies sustain their growth by developing and executing strategies to obtain long-term increases in profitability. Therefore, the income a company uses to fund its long-term growth is the investment that is used to generate an intended return. The programs within the portfolio of programs are the investment vehicles used to generate products, services, or infrastructure capabilities that become the means for achieving the strategic objectives. This investment model is illustrated in Figure 12.1.

This investment model for product, service, and infrastructure development is analogous to a personal investment financial model. As an example, let's look at the investment situation for a private investor named Shannon. Shannon's salary is the income she uses to pay her living expenses and fund her growth in net worth. Without investing a portion of that income in higher-growth investment vehicles, her net worth grows very slowly. If Shannon wants to accelerate the growth of her net worth, she looks for investment vehicles that will generate additional income over and above her salary. If she develops a portfolio of mutual funds, for example, each fund becomes a vehicle for generating additional income. Collectively the portfolio of mutual funds Shannon owns provides continual positive ROI, if managed properly.

A single mutual fund within the private investor's portfolio is analogous to a single program that a business manager invests in to generate a positive ROI for his or her business. Both a mutual fund and a program are vehicles for generating a higher rate of return. To extend this analogy, the private investor and the business manager both define short- and long-term goals they want to achieve and conceive investment strategies for attainment of the goals. They both turn their investment over to someone else to manage—the private investor employs an experienced mutual fund manager, and the business manager employs an experienced program manager. The mutual fund manager manages a collection of stocks that make up the mutual fund, and the program manager manages a collection of projects that make up the program.

The business manager, therefore, delegates the responsibility of managing the ROI for a program to the program manager. Managing the business on the program is the first primary role of the program manager. However, managing the business on a program is not a solo venture. To generate a ROI for a program, the product, service, or infrastructure capability has to be developed by a team of people, all of whom are responsible for developing some aspect of the whole solution. Leading the program team, therefore, is the second primary role of the program manager. Those two roles—managing the business and leading the program team—constitute the responsibilities of the program manager.

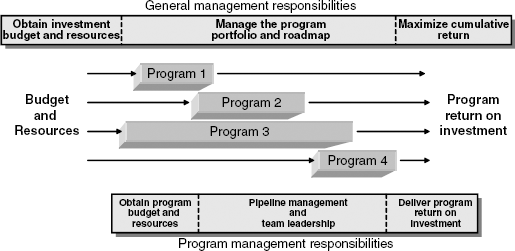

A GM is responsible for managing the investment for his or her business portfolio of programs within a business unit. Three critical elements of a GM's responsibility for managing the investment for his or her business unit are: (1) defining the strategic objectives for the organization; (2) managing the return on his or her development investment (budget, resources, and capital expenditures) by selecting and prioritizing programs within the portfolio that generate the greatest return; and (3) developing a time-phased program road map (see Figure 12.2).

However, if we look at the portfolio of programs and the road map, it is clear that the GM cannot manage the business aspects associated with each and every program (Figure 12.3). As presented in earlier chapters, the responsibility for managing the business for the programs falls upon the program managers within the business unit. Each program manager operates as the GM's proxy, responsible for managing the business aspects of a single program.

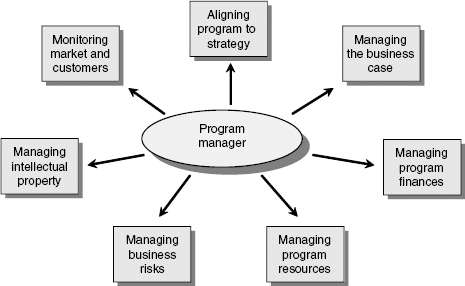

The core responsibilities of the program manager in managing the business aspects of a program investment are described in the following section.

The first primary role of the program manager is to effectively manage all aspects of the business responsibilities bestowed upon him or her by the business unit general manager to achieve the business objectives and results intended. Accomplishing this is, of course, no easy task. As stated earlier, the program manager is acting as the proxy for the GM on his or her specific program. The successful program manager will perform this role in a mature and self-controlled manner. This role requires the program manager to be proactive and to ambitiously pursue the objectives laid out by senior management, while maintaining a great deal of flexibility to adapt as necessary during the life of the program.

There are several elements to managing the business of the program, as depicted in Figure 12.4. We now turn our attention to reviewing each of these elements in greater depth.

The program manager is normally the primary business strategist on a program. He or she needs to continually focus on the strategic business objectives driving the need for the program and for its output. In the define and plan phases of the PLC, the strategic objectives guide the product, service, or infrastructure concept and the end state of the program plan.

A common pitfall within companies is that strong alignment to the strategies of a business is not established during the definition of a program and business case development. Instead, the alignment is attempted somewhere between business case approval and market launch (or system go live), and a misalignment develops between the program and strategic objectives. It is never a pleasant experience for the members of a business unit when they realize that the strategic return on their investment will not be realized due to a misalignment between strategy and execution.

During the tactical phases of the PLC (implementation, launch, and sustain), the program manager continually monitors the business environment within the company to ensure the program remains strategically viable. This is most important for programs with long development cycles which have a greater risk of strategic shifts due to environmental changes. At any point in which misalignment between the program objectives and the strategic objectives develops, the program manager has the responsibility for bringing it to the attention of the senior management team for appropriate resolution.

The program business case establishes the business feasibility and viability of a program and is normally developed as the output of the define phase of the PLC. The program business case is the primary tool for the program manager to manage the business aspects of a program (see Chapter 10.). It is, in fact, the business contract between the program manager and the senior management team of the company, as well as the basis of the program vision for the program team.

The role of the program manager is to drive the creation of the business case based upon the knowledge, information, and data available at the time. There are many unknowns to comprehend early in a program, so establishing and documenting the set of assumptions that the business case is built upon is crucial. For the business case to remain accurate and viable, the program manager needs to continually manage and update the business case as information and data becomes available throughout the PLC.

Part of the business case involves developing a robust set of critical success factors and metrics that are used to determine the viability of the program. Collectively, the critical success factors define business success for the program. They serve as the business objectives that the program team works to achieve, as well as the primary measure of checks and balances to guide decisions and to evaluate environmental changes.

At any point in the development cycle in which the business case no longer looks viable, the program manager must communicate that to the senior sponsors of the program. This, at times, can be difficult due to emotional and organizational culture factors, but as the GM proxy on a program, the program manager must manage the ROI. This usually means managing the program to success, but it can also mean cutting the losses as early as possible and recommending to cancel the program if the investment is no longer viable.

Once a program is approved or awarded, the investment funds are transferred to the program manager for management. In some cases, especially within firms utilizing traditional phase/gate development processes, funds may be released in conjunction with achieving specific key gates. The investment funds may come from various sources such as lending institutions, venture capital companies, shareholders, customers, or internal funds. This involves managing the program cash flow and managing the cost of goods sold. It is recommended that a program manager has a financial analyst on the PCT to help manage the financial aspects of a program, as managing program finances can be a time consuming activity. Historically, the relationship between the program manager and the financial analyst has been contentious due to competing agendas of the two job functions. The job of the financial analyst is to keep the program financially viable by controlling costs. Cost control, however, can be viewed as constraining to the program manager who is being challenged to manage and balance all of the competing objectives, including cost control. However, great benefits can be gained if the program manager forges a strong working relationship with his or her financial analyst, as shown in the box titled, "Knowing the Numbers".

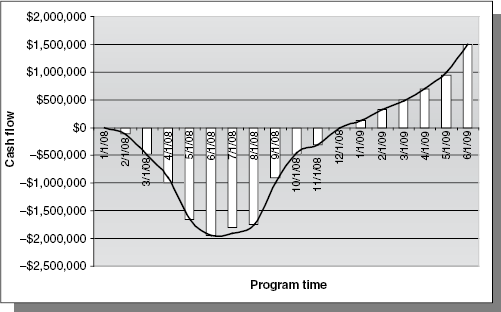

Managing the program cash flow involves more than just monitoring the total available program budget. It involves understanding and monitoring program expenditures and income on a periodic basis. All companies have to make money to stay in business, and the ability to maintain a positive cash flow is a critical component of an organization's success. This is especially true for smaller companies, start-ups, and any company that is not cash rich.[132]

Once a program is funded, management of cash flow for the program becomes the responsibility of the program manager. It is risky to monitor the program budget in total. If, for example, the budget was depleted three quarters of the way through a program, the team would suddenly be in trouble with respect to program finances, and most likely work would come to a halt (at least temporarily). For this reason, the program manager along with the program financial analyst should create a cash flow plan for the budget and then manage program finances to the plan. When a periodic cash flow plan is established (see Figure 12.5), deviations from the plan are much easier to react to and manage. This supports the 'no surprises to management' philosophy that we subscribe to.

Understanding the billing and payment terms of the company, its suppliers, and its customers should be understood and reflected in the cash flow plan. There is a time delay for both expenditures and income generated by a program due to billing cycles. For example, the organization sponsoring a program may have payment terms of 90 days after receipt of goods from its suppliers. This means that expenditures for the program are delayed by three months. Likewise, revenue generated by the program will also be subject to the payment terms of a company's customers.

Managing the program scope is one of the most critical aspects of managing the cash flow on a program. Increases in program scope without increases in funding (commonly referred to as "scope creep") will negatively affect a program's cash flow. It is imperative that the program manager be aware of any work outside of the planned scope and of the financial impact of that work. For this reason, an effective change management process should be in place (see Chapter 8) to manage changes in the program scope.

The final aspect of managing program cash flow involves knowing when to ask for assistance from the senior management team of the business. Short-term and long-term program cash flow assistance can only be provided by senior management, and the program manager must be willing to work with the executive team to secure the finances needed to continue the program.

The second aspect of managing the return on invested funds is the management of the cost of goods sold. The cost of goods sold includes the bill of materials and the cost associated with manufacturing, assembling, or otherwise physically creating the product, service, or infrastructure capability under development. The cost of goods sold is deducted from the revenue generated for each unit sold or used in the case of a service. Minimizing this cost through actions during the development cycle enables a company to retain a larger percentage of the sales revenue or cost savings generated once the product, service, or infrastructure capability is launched.

The program manager and his or her program team are responsible for driving the future cost of goods sold to a minimum as part of the development process. Cost of each component of the product, service, or infrastructure capability, as well as the total number of components, makes up the cost of the final unit. Many cost versus performance trade-off decisions are made during the development process to generate an optimum bill of material cost that achieves the performance requirements of the program. The program manager's role is to set aggressive, yet realistic, bill of material cost goals for the program team. Then he or she must measure progress toward achievement of the cost goals through the use of program metrics (see Chapter 9).

Like management of bill of material cost, managing the cost to manufacture, assemble, or create the final product, service, or infrastructure capability is the responsibility of the program team. The role of the program manager is to set aggressive, realistic goals to drive the most efficient and cost-effective approach for creating the product, service, of infrastructure capability under development.

Much of the funds invested in a program are utilized to pay for the resources needed to complete the work. This includes both human and nonhuman resources. Resource cost is by far the largest consumer of the investment budget, in many cases constituting more than 75 percent of the program budget. For this reason, effective management of the program resources is a critical aspect of the business management role of the program manager.

Developing a viable business case, aligning a program to the strategic objectives of a company, and managing the program finances are critically important aspects of the program manager's role; however, if he or she cannot secure and maintain the resources to complete the work, the strategic, business, and financial goals of a program will not be achieved. Therefore, resource management is a key factor in program success—equally important as the financial, time, and quality aspects of a program.

To be completely successful, a program must be adequately resourced. There is a high level of uncertainty with respect to resource utilization when program plans are initially generated. For that reason, resource management needs to be viewed as a continuous process that takes place throughout the PLC.[133]. A common pitfall that we have observed is that a lot of effort goes into generating a program resource plan and gaining commitment from resource managers to fulfill the resource demand of the program. However, once the plan is approved, focus shifts to other aspects of the program, and resource constraints begin to mount. The role of the program manager is to manage resource utilization throughout all phases of the PLC.

Resource management involves the program manager understanding the skills, experience levels, and number of resources needed for a program. Then he or she must work with the organization's functional managers to adequately staff the project managers and individual contributors needed for the program. The program manager is first responsible for ensuring the core team is fully staffed. This means each project has a qualified project manager in place and represented on the core team. Further, each critical function supporting the program should have a qualified representative as a member of the PCT. Secondly, the program manager is responsible for working with each project manager to be sure that his or her team is adequately staffed. When resource constraints are identified on a project, the program manager assists the project manager in resolving the constraint as effectively as possible and, if necessary, adjusting the project plan and program plan to take the constraint into account. Resolution usually entails adjustments to program costs, resources, time, performance, or quality goals. At any point in a program in which resource gaps adversely affect the program critical success factors, the risk must be communicated to the senior management team of the business unit for assistance in resolution (see the box titled, "Resources Management that Hurts").

The financial world teaches us that all investment involves some level of risk. Developing products, services, and infrastructure capabilities are no different. Various levels of risk taking are necessary if a company is intent on being a leader, or even a strong contender in its industry. Market leaders understand that they must run directly toward, instead of away from risk to put distance between themselves and their competitors. This means that development programs can have a high level of business risk associated with them. Failure to identify and understand the risks, or uncertainties, can lead to substantial loss for the enterprise. The role of the program manager is to protect the company's investment in the program through effective management of the business risks involved.

Risk is inherent in every program—it comes with the territory. Good risk management will not make the risk associated with a program go away; it merely helps to ensure that the program team will not be blind-sided with a problem to which they cannot respond.[138] The program manager must be aware that the failure of a single project within a program can cause the entire program to fail. This requires that the program manager empower the project managers to manage the project-level risks and focus his or her efforts on identifying and managing the program-level risks (see Chapter 8). The role of the program manager is to be an advocate for effective risk management practices on the program and ensure that it becomes an institutionalized practice on the program. The program manager needs to keep the entire program team engaged in risk management practices, as risk management becomes useless if only a small number of program team members effectively practice it.

IP may have significant strategic and commercial value to a company. Much of the IP generated by companies engaged in product, service, or infrastructure development is done so within the context of development programs. For these reasons, a crucial element of managing the business on a program involves the proper management of the IP created. This may include making sure that the proper patents, trademarks, and copyrights are obtained, depending upon the type of IP created (see box titled, "Intellectual Property of Another Kind").

The motivation for management of intellectual property is maximization of profit. For a high-technology company, IP is the engine of survival and growth. It is of utmost importance for managers to build a corporate culture that appreciates such a view.

IP is the know-how that is produced by our creative minds. In particular, it is the knowledge of doing something in a better way. It is also the knowledge to figure out that this better way may be very profitable if it can be commercialized. If a company patents its technology, for example, it would prevent others from using it without paying for its use.

It is not a job of program managers to know the ins and outs of managing intellectual property. Multiple players such as technologists, managers, functional managers, directors, legal experts, and officers all take part in managing IP. However, program managers must first understand that it is the IP portfolio that keeps profitable technology companies in their leading market positions. Second, they must have a developed sense for the following questions:

Is there a competitor who could use the IP developed on my program to compete against us?

It means that the program manager should know the market and customers and have a good understanding of the competitive analysis.

If so, what does that mean to my program's business?

Again, good knowledge of market, customers, and competitors, along with the program business case will help the program manager understand the answer to that question.

What can be done to protect the IP?

There are multiple ways to protect IP. For example, either patenting a new technology or idea or requiring nondisclosure agreements with all partners.

The program manager should use this knowledge to ensure that all players involved play the game in a way that benefits the program because, ultimately, the program manager owns the program success.

Besides a strong internal focus on the business of the program, the program management role also requires an external focus on the market and continual monitoring of market conditions. The market consists of the customers who buy the product, service, or infrastructure capability; the end users who will use it; and the competitors who are trying to sell their solutions to the same customers. There are many examples of program managers who have focused their attention solely on the effective use of their resources to achieve the goals of the program—all the while being unaware of shifts in the external market that have left their solution ineffective and unattractive to the customers and end users.

The best program managers continually monitor the state of the external environment to check if the business objectives and strategies that the program is based upon are still achievable. In particular, to keep a program feasible, from the business and strategic perspective, the program manager and other key members of the program team should be fully aware of the current state of the market (internal or external) in which the business operates and also be aware of emerging trends. To determine the current state and future trends of the market, the program manager needs to be engaged with the customer and bring the customer information back to the program team. It is crucial that program managers understand the wants and needs of their customers to obtain business success for the program.

However, it is even more important for them to understand the needs of the end-user. This is a critical distinction. In many cases, the customers and the end users are two different sets of people—the customer is the one who purchases the program output from the manufacturer, while the end user is the one who actually uses it. For example, a retail outlet is a customer of a digital camera manufacturer such as Kodak, but the person who buys it from the retailer and uses it for his or her personal use is the end user. It is the needs of the end user that must be transformed into the functional requirements of the product, service, or infrastructure capability. Therefore, the program manager and key members of the program team need to find ways to interface directly with end users. This may be accomplished by developing focus groups, directly observing end users, or developing prototypes for the end users to test. For an example of a creative approach to garnering end-user interface, see the box titled, "From the Design Room to the Showroom".

Program managers also need to understand who the competitors are and what they have to offer. To create a competitive advantage, it requires that competitors are known, that the competitor's solutions are understood, that the solution being developed by the program team can be compared to competitor's solutions, and that the differences between the solutions and the value proposition of the program team's solution can be explained to potential customers.

This exercise is often conducted by program teams but is treated as a one-time event either as part of the concept approval or the business case. However, to ensure competitive viability of the product, service, or infrastructure capability under development, this exercise needs to be repeated periodically—at least at every phase/gate review.

An appropriate level of marketing expertise on the part of the program manager is important for the following reasons:

To achieve the business objectives intended, the product, service, or infrastructure capability must solve the problems and meet the needs of the customers and end users.

Market knowledge improves the team's understanding of how the end users will utilize the program output.

Market knowledge assists the program team in defining the product, service, or infrastructure quality expectations of the customers and end users. Quality goals that are too low result in customer dissatisfaction, and quality goals that are too high result in unnecessary cost to the business.

Stronger knowledge of the market facilitates better decisions on the part of the program manager, the members of the program team, and the executive stakeholders.

A much stronger business case can be developed when knowledge of the market is utilized—such as market size, market segmentation and sales potential of each segment, and customer and end user problems and needs. Market information will increase the probability of program and business success.

In program management, like any other discipline, there is a distinct difference between good program managers and great program managers. Good program managers are those that can manage the business and operational aspects of a program. Great program managers are those that have the ability to combine strong management skills with strong leadership skills. The primary differentiator between good and great is one's ability to lead the program team toward the achievement of the business objectives. The strong leader establishes a vision, or end state, and then guides the work of the entire team toward that vision, while helping the team to establish pride in their work as well as knowledge of how their work contributes to the program goals.[140]

A combination of strong management and leadership abilities is what separates the best from the rest. The program manager uses his or her management skills to utilize the physical resources (human skills, raw materials, and technology) of the enterprise to ensure that the work of the team is well planned out, is performed on schedule and within cost, is delivered with a high level of quality, and is executed productively and efficiently. However, because program managers rarely have resources directly reporting to them, they must use strong leadership skills to build relationships to influence, focus, and motivate the program team. In doing so, program managers utilize the emotional and spiritual resources of the organization to create and deliver great things.

So why is it important that program managers be both effective managers and effective leaders? The answer to that question is contained in Chapter 2—programs are complex by nature. The quickening pace of innovation has led to more complex solutions to meet the needs of both customers and end users. The high level of solution complexity has led to more specialization to breakdown the complexity into smaller elements that can be more easily managed. However, the challenge remains that the development team becomes fragmented into specialized work teams that are organized around the various elements of the product, service, or infrastructure solution. Pulling this group of functional specialists into a cohesive, effective team that is focused on a common set of objectives requires both leadership and management skills. Strong management skills are needed to organize the team and make sure the work is accomplished productively. Strong leadership skills are needed to ensure that the team members are performing as a single entity that identifies with the program more than their functional specialty and that they remain focused on a common vision of what they are trying to achieve.

It is fairly easy to recognize a program that is lead by a program manager who lacks strong leadership skills. It is normally characterized as a loose grouping of functional specialists who operate only within their area of specialty, functional agendas and goals take precedence over a common vision and goal, and there is a high level of dysfunction between the functional elements on the program. This results in a low level of interplay between the specialists and a high level of finger pointing and cross-functional accusation when the elements do not integrate into a common solution. If this situation sounds familiar, it is probably an indication that the second primary role of the program manager, that of leading the team, is not well understood within the business.

Leaders take people where they need to go and help them understand how their efforts contribute to the goals of the organization. For the program manager, this means that he or she is responsible for keeping the team of functional specialists performing as a cohesive group to achieve the objectives of the program, while helping each project team understand how their element contributes to the creation of the whole solution. To accomplish this, the leadership role of the program manager consists of three primary elements, as follows:

Establishing the program vision

Empowering the PCT

Navigating change and risk

The foundational element of creating a cohesive, high-performing team is to establish a common vision for the program and then work through others to achieve that vision. The program vision is the end state that the program is trying to achieve. In most cases, it is the set of business objectives that the program is commissioned to achieve and is commonly referred to as "the big picture." Everything that happens on a program should do so in the context of the big picture, or program vision.[141]

One of the essentials of strong leadership is that the leader pulls upon the energy and talents of the team, rather than pushing, ordering, or manipulating people. Leadership is not about imposing the will of the leader, but rather about creating a compelling vision that people are willing to support and exert whatever energy is needed to realize it.[142] The program vision is the device that the program manager uses to pull the team together and to keep the project specialists focused on the cross-functional goals, rather than just the goals of their specific function. It is the basis of empowerment that allows the program manager to establish power of influence, rather than power of expertise. For an example of personal leadership principles one practicing program manager has developed, see the box titled "The Story of Leadership of a World-Class Program Manager".

One of the biggest leadership challenges for the program manager is maintaining the program vision despite the large number of potential distractions that occur in any given day during the life of a program. These distractions create noise in the system that can cause the program stakeholders to lose focus on the goals of the program and forget what the program is all about.[143] It is important that the program manager remains diligent in maintaining and constantly communicating the program vision to all stakeholders, the program team, and sponsors in particular throughout the PLC.

To lead, one must have a relationship with people who are willing to follow. For the program manager, those people are the PCT specifically and, generally, the entire program team. Every leader's potential is determined by the abilities and actions of the people that are closest to him or her. If the leader's inner circle of people are strong and capable, the leader can make a big impact within an organization.[144] This is true for the program manager whose inner circle consists of the members of the PCT. As discussed in Chapter 5, careful selection of the PCT members is critically important for this reason. First and foremost, program managers should select core team members who are experts in the function that they represent within the organization. The second critical criteria for PCT selection is a person's ability to step outside of their area of expertise to effectively collaborate with the other members of the leadership team toward the achievement of the program vision. One of the most significant ingredients for program success is the cooperation and collaboration between the project teams within the program, in which everyone understands that they cannot succeed unless everyone else succeeds.[145]

The program manager empowers the core team by giving away a portion of his or her own power to the project managers. Thus, the project manager will succeed by exercising control over his or her own decisions and resources. This is an important concept for a program manager to grasp. Nothing is more disempowering than giving the core team a lot of responsibility for program success, then not providing them with the resources and the ability to work autonomously. Effective leaders get the most out of the members of their inner circle by treating them in a way that bolsters their self confidence and provides them with the necessary resources to succeed.[146] A strong sense of self confidence makes it possible for the PCT members to take control of their portion of the program, which allows the program manager to focus on the big picture and the interdependencies between the teams.

Establishing an environment of "no fear" is also a critical element in developing a team's confidence, according to a senior program manager for a major aerospace company. As he told us,"A no fear environment is needed so people don't have to fear coming to the program manager with the real answer, especially if it's not a pleasant answer. You have to let people stumble a bit in order for them to learn and gain confidence."

Leadership is directly tied to the process of creating innovative solutions.[147] Innovation by nature causes change, and change requires leadership to move people in a new direction.[147] It also requires a higher level of risk taking to try new ideas and solutions. Change, risk, and leadership are tightly intertwined. Good leaders will foster a climate of risk taking to empower their teams to step outside of their comfort zones and try untested ways to innovate.[148]

The role of the program manager is to be an agent for change on the program and to create a climate that supports risk taking. This empowers the program team to find innovative solutions for the solutions they are developing.

Some program managers that we talked with believe that the sign of a strong leader is to have the right answer for every question and problem that comes their way, without having to escalate to senior management. In reality, as the leader of the program team, a program manager will not get rewarded for just being right. Rather, success is rewarded by leading a team of people toward the attainment of the business objectives that they are commissioned to achieve.

This is accomplished by effectively leading people to work at a high level of performance and to effectively collaborate as a cohesive team. To lead, the program manager must have a team of people who are willing to follow. People will only voluntarily follow someone who they believe is credible and has the ability to lead them to success. Strong leaders, therefore, must possess and demonstrate the following attributes:

Vision

Trustworthiness

Credibility

Competency

For program managers to create pull and influence the team to follow in the direction they have set, their vision must be clear, compelling, and achievable. The effective program manager continuously works to communicate the vision and to align the team in support of it. The program vision is the primary mechanism for pulling a team of functional specialists together to work in a collaborative manner.

At the heart of collaboration is trust. Trust is the fundamental cornerstone of human relationships, and without trust one cannot lead.[149] Program managers must continuously demonstrate that they are trustworthy and that they expect the same from all members of the program team. As John Maxwell states in the highly acclaimed book, The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership:[141]

People will tolerate honest mistakes, but if you violate their trust, you will find it very difficult to ever regain their confidence

Program managers need to possess a high degree of integrity and be consistently trustworthy. They need to take total responsibility for their own actions as well as the actions and results of their teams.

People will refuse to follow those they do not deem credible. To maintain credibility, the program manager must continuously do what they say they will do and always let people know where they stand on issues and stick to it. A program manager that fails to follow through on his or her commitments, or who vacillates on issues concerning the program, will have a difficult time convincing the team that they have the credibility to lead them to success.

Just as people will refuse to follow those they do not perceive as credible, they will also refuse to follow leaders they feel are not completely competent. Competency implies that the leader is organized and disciplined in all activities and will expect that of others. As the leader of the program, team members expect the program manager to lead by example and actively participate in accomplishment of the program goals.

The programs within the portfolio of programs are the investment vehicles used to generate products, services, or infrastructure capabilities, which are the means for achieving ROI and other strategic objectives. A business unit manager is not able to manage the business aspects of all the programs within the portfolio. He or she, therefore, must delegate business responsibilities for managing the ROI for the programs to the program managers within his or her organization. This responsibility includes the following two roles: managing the business and leading the team. The first role, managing the business, includes the following:

Aligning program with business strategy

Developing and managing the business case

Managing the program finances

Managing resources

Managing intellectual property

Managing business risks

Monitoring the market and customers

The second role, leading the team, involves the following:

Establishing the program vision

Empowering the PCT

Navigating change and risk

To successfully fill these two roles, the program manager has to possess strong leadership and management competencies.

[132] Stagliano, A. R. "Cash is the Lifeblood of Every Contractor". Building Profits Magazine (2005).

[133] Keogh, Jim, Avraham, Shtub, Jonathan F. Bard, Shlomo Globerson. Project Planning and Implementation. Needham Heights, MA:Pearson Custom Publishing, 2000.

[134] Repenning, N. "Resource Dependence in Product Development Improvement Efforts" Cambridge, MA: Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1999).

[135] Adler, P. A., Mandelbaum, et al., "Getting the Most out of Your Product Development Process," Harvard Business Review (March-April 1996)

[136] Jagtap, M. "Analysis of Persistent Firefighting". Portland, OR: Department of Engineering and Technology Management, Portland State University (2005)

[137] Herweg, G. and K. Pilon "System Dynamics Modeling for the Exploration of Manpower Project Staffing Decisions in the Context of a Multi-Project Enterprise". Cambridge, MA: System Design and Management Program, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2001).

[138] Demarco, Thomas and Timothy Lister. Waltzing With Bears: Managing Risk on Software Projects. New York, NY: Dorset House Publishing Company, (2003.

[139] "HP gets closer to users by design," The Oregonian, (Friday January 6, 2006).

[140] Bennis, Warren G. and Burt Nanus. Leaders: Strategies for Taking Charge, 2nd edition. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997.

[141] Maxwell, John C. The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership. Nashville, TN:Thomas Nelson, Inc Publisher, 1991: pp. 58.

[142] Kouzes, James M. and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003: pp. 143.

[143] Kouzes, James M. and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003: pp. 114.

[144] Maxwell, John C. The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, Inc Publisher, 1991: pp. 110.

[145] Kouzes, James M. and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003: pp. 250.

[146] Kouzes, James M. and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003: pp.307–322.

[147] Kouzes, James M. and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003: pp. 187.

[148] Kouzes, James M. and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003: pp. 207.

[149] Kouzes, James M. and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003:pp. 224.