CHAPTER 32

Cultural Challenges in Managing International Projects

A backhanded “V for victory” sign is an uncomplimentary gesture in Australia. In Brazil, the American “A-OK” sign is also offensive. These are lessons that some presidents, diplomats, and businesspeople have learned the hard way. Awareness of such cross-cultural subtleties can spell success or failure in international dealings, whether in diplomatic relations, general business, or the project arena.

Projects conducted in international settings share these sometimes embarrassing communications pitfalls and others as well. They are subject to cultural, bureaucratic, and logistical challenges just like conventional domestic projects are. In fact, project management approaches to international ventures include the same items common to domestic projects. Under both circumstances, successful project management calls for performing the basics of planning, organizing, and controlling. This also implies carrying out the classic functions outlined in the Project Management Institute’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®) of managing scope, schedule, cost, quality, communications, human resources, contracting and supply, and risk, as well as the integration of these areas across the project life cycle.

Understanding culture is the starting point for planning for the challenges that face international projects. The American Heritage Dictionary defines culture as, “The totality of socially transmitted behavior patterns, arts, beliefs, institutions, and all other products of human work and thought characteristic of a community or population.” For an organization, culture may be more simplistically perceived as the guiding beliefs that determine the “way we do things around here.” The challenge in international project settings revolves around the fact that projects are usually made up of multiple organizations, thus involving multiple organizational cultures in settings that involve several ethnic or country-based cultures. An example is an Anglo-American joint venture working in Saudi Arabia, with Japanese and Indian subcontractors. So the issues are actually cross-cultural in nature and involve multiple issues.

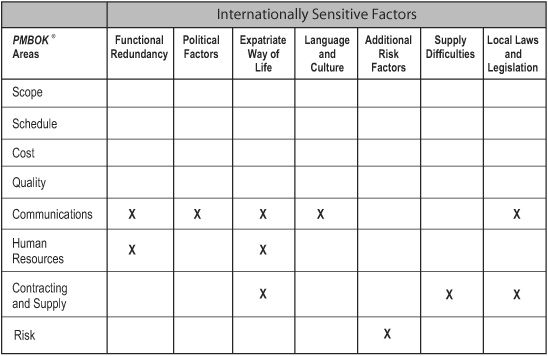

The primary factors in cross-cultural settings that call for special attention and an “international approach” are: functional redundancy, political factors, the expatriate way of life, language and culture, additional risk factors, supply difficulties, and local laws and legislation. Of the items pinpointed, some offer particular challenges from the viewpoint of the PMBOK® Guide. Some comments on these critical topics follow. These are the subjects that require special care to ensure that the internationally set project meets its targeted goals.

FACTORS REQUIRING SPECIAL ATTENTION IN CROSS-CULTURAL SETTINGS

![]() Functional redundancy means the duplication or overlap of certain functions or activities. This may be necessary because of contractual agreements involving technology transfer requiring “national counterparts.” Language or organizational complexity of the project may also be responsible for creating functional redundancy. Special attention is called for, therefore, in managing the project functions of human resources and communications.

Functional redundancy means the duplication or overlap of certain functions or activities. This may be necessary because of contractual agreements involving technology transfer requiring “national counterparts.” Language or organizational complexity of the project may also be responsible for creating functional redundancy. Special attention is called for, therefore, in managing the project functions of human resources and communications.

![]() Political factors in international projects are a strong influence and are plagued with countless unknowns. Aside from fluctuations in international politics, project professionals are faced with the subtleties of local politics, which often place major roadblocks in the pathway of attaining project success. In terms of classic project management, this means reinforcing the communications function in order to ensure that all strategic and politically related interactions are appropriately transmitted and deciphered.

Political factors in international projects are a strong influence and are plagued with countless unknowns. Aside from fluctuations in international politics, project professionals are faced with the subtleties of local politics, which often place major roadblocks in the pathway of attaining project success. In terms of classic project management, this means reinforcing the communications function in order to ensure that all strategic and politically related interactions are appropriately transmitted and deciphered.

![]() The expatriate way of life refers to the habits and expectations of those parties who are transferred to a host country. This includes the way of thinking and the physical and psychological needs of those people temporarily living in a strange land with different customs and ways of life. When the differences are substantial, this means making special provision for a group of people who would otherwise refuse to relocate to the site, or, if transferred on a temporary basis, remain highly unmotivated during their stay. The basic project management factors related to the expatriate way of life include communications, human resources, and supply. Personal safety issues may affect the coming and going of expatriates and family members.

The expatriate way of life refers to the habits and expectations of those parties who are transferred to a host country. This includes the way of thinking and the physical and psychological needs of those people temporarily living in a strange land with different customs and ways of life. When the differences are substantial, this means making special provision for a group of people who would otherwise refuse to relocate to the site, or, if transferred on a temporary basis, remain highly unmotivated during their stay. The basic project management factors related to the expatriate way of life include communications, human resources, and supply. Personal safety issues may affect the coming and going of expatriates and family members.

![]() Language and culture include the system of spoken, written, and other social forms of communication. Included in language and culture are the systems of codification and decodification of thoughts, beliefs, and values common to a given people. Here all the subtleties of communications become of special importance.

Language and culture include the system of spoken, written, and other social forms of communication. Included in language and culture are the systems of codification and decodification of thoughts, beliefs, and values common to a given people. Here all the subtleties of communications become of special importance.

![]() Additional risk factors may include personal risks such as kidnapping, local epidemics, and faulty medical care. Terrorism and local insurgencies are also critical risk factors in some settings. Rapid swings in political and economic situations, or peculiar local weather or geology, are also potential uncertainties. These different risk factors require analysis and subsequent management to keep them from adversely affecting the project. The obvious basic project management tenet in this case is risk management.

Additional risk factors may include personal risks such as kidnapping, local epidemics, and faulty medical care. Terrorism and local insurgencies are also critical risk factors in some settings. Rapid swings in political and economic situations, or peculiar local weather or geology, are also potential uncertainties. These different risk factors require analysis and subsequent management to keep them from adversely affecting the project. The obvious basic project management tenet in this case is risk management.

![]() Supply difficulties encompass all the contracting, procurement, and logistical challenges that must be faced on the project. For instance, some railroad projects must use the new railway itself as the primary form of transportation for supplies. In other situations, waterways may be the only access. Customs presents major problems in many project settings. A new concept in logistics may need to be pioneered for a given project. Contracting and supply on international projects normally calls for an “overkill” effort, since ordinary domestic approaches are normally inadequate. This usually requires highly qualified personnel and some partially redundant management systems heavily laced with follow-up procedures. Heavy emphasis is needed in the areas of contracting and supply.

Supply difficulties encompass all the contracting, procurement, and logistical challenges that must be faced on the project. For instance, some railroad projects must use the new railway itself as the primary form of transportation for supplies. In other situations, waterways may be the only access. Customs presents major problems in many project settings. A new concept in logistics may need to be pioneered for a given project. Contracting and supply on international projects normally calls for an “overkill” effort, since ordinary domestic approaches are normally inadequate. This usually requires highly qualified personnel and some partially redundant management systems heavily laced with follow-up procedures. Heavy emphasis is needed in the areas of contracting and supply.

![]() Local laws and legislation affect the way much of business is done on international projects. They may even affect personal habits (such as abstaining from drinking alcoholic beverages in Muslim countries). Here the key is awareness and education so that each person is familiar with whatever laws are applicable to his or her area. In this case, the project management tenets that require special attention are communications and supply.

Local laws and legislation affect the way much of business is done on international projects. They may even affect personal habits (such as abstaining from drinking alcoholic beverages in Muslim countries). Here the key is awareness and education so that each person is familiar with whatever laws are applicable to his or her area. In this case, the project management tenets that require special attention are communications and supply.

The Integration Knowledge Area, of course, combines all these in an even more complex web.

FIGURE 32-1. RELATIONSHIP OF INTERNATIONALLY SENSITIVE FACTORS TO THE BASIC CONCEPTS OF THE PMBOK®GUIDE

It is apparent from Figure 32-1 that in terms of classic project management, special emphasis is required on international projects in the areas of communications, contracting and supply, human resources, and risk. Since all of the project management areas—including the basic areas of managing scope, schedule, cost, and quality—are interconnected (a communications breakdown affects quality, for instance), extra diligence is called for in managing communications, contracting and supply, human resources, and risk. It must be assumed that a conventional approach to managing these areas will be inadequate for international projects.

A MODEL OF INTERCULTURAL TEAM BUILDING

The challenge in international team building boils down to creating a convergence of people’s differing personal inputs toward a set of common final outputs. This means developing a process that facilitates communication and understanding between people of different national cultures. Making this process happen signifies the difference between success and failure on international projects.

People’s inputs are things like personal and cultural values, beliefs, and assumptions. They also include patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Expectations, needs, and motivations are also part of people’s inputs into any given system. The outputs are the results or benefits produced by a given system. They may be perceived as a combination of achievements benefiting the individuals, the team, the organization, and the outside environment. The outputs are the object of the efforts generated by the inputs.

The secret is to transform the way people do things at the beginning of the project into more effective behavior as the project moves along. This transformation initially involves identifying the intercultural differences among the parties. Once this is done, a program of intercultural team building is called for in order to make the transformation take place. The result of the team-building process is to influence the behavior of the group toward meeting the project’s goals. Intercultural team building thus calls for developing and conducting a program that will help transform the participants’ inputs into project outputs.

SOME GLOBAL CONSIDERATIONS

Globalization affects all areas of endeavor, including how projects are managed. It affects the internationally sensitive factors mentioned earlier in this chapter and reinforces the need to create teams that are capable of dealing with the dynamics of globalization.

The groundswell toward globalization stems from a number of factors, from advances in transportation and communications technologies through international trade agreements. New international standards, replacing national standards that impeded the movement of goods and services, also open doors toward a more globalized economy.

While the trends toward globalization of project management and related technologies such as the construction industry are apparent, there still remain basic differences in the way business is performed from one land to the next. A contrast between the United States and Japan appears, for instance, when examining the relationship between general contractor and architects. This relationship is traditionally adversarial in the United States, as is reflected by the habitual finger-pointing that goes on at the end of contracts, sometimes resulting in litigation. In contrast, in Japan these relationships are much more cooperative in nature; there is a certain congeniality between design and construction. Also in contrast, mutual risk-taking between contractors and clients is a more common practice in Japan than in the United States. It is a common practice in Europe as well. Meanwhile, partnering—one form of mutual risk-taking—is growing in the United States, but it is almost routine procedure in Japan and Europe.

Information technology projects are becoming increasingly globalized, largely due to massive outsourcing of services to parts of the world where the expertise exists and cost is less than in highly developed countries. Some manufacturing projects are highly globalized, both in terms of development as well as fabrication. Such is the case in aircraft manufacturing, where components are developed and manufactured in sundry parts of the world and then consolidated at a central location.

The way technical information is developed and transferred also affects how business is performed, and consequently, how projects are managed and implemented. Various systems or models are in place for generating and transferring knowledge in different parts of the world. Here are some of the models applicable to the construction industry. In general terms, the basic models may be called the European, the North American, and the Japanese. (These terms are used only to identify trends, as all three models can be found in most countries.) The characteristics of the models are as follows:

The European Model

In Europe, there are highly structured, formal, and centralized national systems for generating and disseminating technical knowledge. Responsibilities are clearly defined, with specific national organizations charged with generating research, while other organizations take care of transferring the result to industry. The Swedish system is a typical example, with the National Swedish Institute for Building Research responsible for knowledge generation, and the Swedish Institute for Building Documentation responsible for dissemination. National systems in Europe are often jointly financed by government and industry.

The North American Model

The system in North America is less formal than in Europe. There is, in fact, little coordination in the construction research effort in North America. In contrast to the European model, advanced construction knowledge is mainly generated at the university level. The dissemination to industry is largely performed by broad-based engineering or trade associations, such as the American Society of Civil Engineers and the Construction Industry Institute. The technical work is carried out in these associations partially by committees made up of volunteers.

The Japanese Model

In the Japanese model, research is concentrated in a handful of integrated companies that dominate Japanese construction, where technology development is considered a significant competitive tool. Therefore, as much as $100 million is invested annually by those companies, which is considered proprietary and subject to commercial confidentiality. Companies invest in research to attain competitive advantage.

In spite of these differences in philosophy and style, globalization is evident at every level of the construction industry—from material, through manufactured goods, to services. The general trend in international industrial research and development is toward strategic alliances and joint ventures to reduce the risk factor and share the spiraling costs.

Governments are now changing previous policies aimed at achieving regional goals in favor of sponsoring research and development at the multinational level. Examples are projects such as Airbus and jointly funded R&D programs underwritten by the European Community. While there is sharing going on, which points to increased globalization, the fight for the competitive edge is always under way.

Another factor that influences managing projects internationally is the increasingly active role being taken by the owner organizations in the management of their projects. In the case of developing countries, this often reflects a national policy aimed at attaining greater managerial and technical capability so as to be less dependent on the developed world. Owners in such countries have a need for contracting services toward getting their project completed as well as transferring experience to their own organizations.

The globalization of project management information and know-how takes place through independently published literature and through two major internationally recognized organizations that are dedicated exclusively to the field of project management—PMI (the Project Management Institute) and IPMA (International Association of Project Management)—both of which are affiliated with numerous other organizations with related interests. Another association with significant published literature in project management is the AACE (the American Association of Cost Engineers).

INTEGRATING TWO CULTURES

While globalization is an ongoing influence on the management of international projects, success depends primarily on giving the proper emphasis to those factors that are particularly vulnerable in cross-cultural settings and on building a team capable of dealing with the challenges presented.

This discussion is drawn from the experience of co-author Codas in the management of “binational projects” in South America that involved the merging of cultures of projects jointly owned by the governments of two countries bordering rivers of staggering hydroelectric potential.

It is common practice in binational projects to have formal authority shared by two people, one from each country. This shared authority ranges from an integrated partnership of managers to a lead-manager/backup-manager situation.

Binational projects are products of hard political processes that involve long and difficult negotiations. In most cases each side has a different perception about the adopted solution, and during the project phase each side may try to “win back” some of the points initially “lost” at the negotiating table. The final diplomatic agreements are lengthy texts that are usually rich in political rhetoric and poor in operational and technical considerations. This sets the stage for conflict during the implementation phase of the project. The need for strong communications management becomes immediately evident in such a setting. An additional complicating factor is the fact that diplomatic documents contain writing “between the lines” and are consequently not easily decipherable by project managers and engineers.

Most binational agreements for developing projects state a philosophy of equity regarding the division of the work to be executed by each side. The unclear definition of what “equal parts” means is the prime source of inbred interest-based conflicts, which also affect the culture of the project.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF A PROJECT CULTURE

Experience in managing binational projects indicates that, for cultural convergence to take place, managers of both sides need to understand the culture of the other side, analyzing the different patterns that make up that culture. This means learning the other country’s history, geography, economy, religion, traditions, and politics. Both sides, therefore, need to become fully aware of basic differences involving educational level, professional experience, experience on this kind of project, knowledge of the language, and host country way of life.

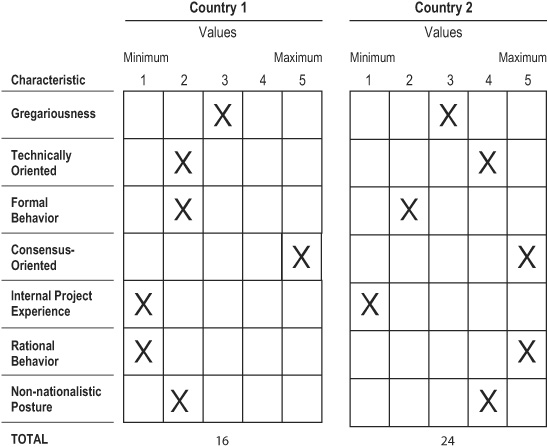

Aside from this information, which can be readily obtained and assimilated, other perceptions must be taken into consideration, such as beliefs, feelings, informal actions and interactions, group norms, and values. These factors strongly affect behavior patterns. A simple way of tabulating the different factors that affect cultural behavior is shown in Figure 32-2. Although the judgment criteria are basically subjective, the chart pinpoints some of the basic differences in culture that tend to affect managerial behavior. In the binational situation used as a basis for this discussion, both sides filled out the charts and jointly evaluated the results.

FIGURE 32-2. EVALUATION OF CULTURAL PATTERNS OF TWO COUNTRIES INVOLVED IN A JOINT VENTURE

Based on the analysis of the cultural differences, behavioral standards need to be developed. The objective is to define a desirable behavior or a “project culture” most suitable to the project objectives and the group’s culture. In other words, cross-cultural team building must take place so that the individuals’ inputs can be effectively channeled to meet the project goals. Forming a project culture is a project in itself; therefore, it must have an objective, a schedule, resources, and a development plan. Its execution becomes the responsibility of the management team. The objective of building a project culture is to attain a cooperative spirit, to supplant the our-side-versus-your-side feeling with a strong “our project” view. The project culture is developed around the commonalities of both groups, identified in the analysis shown in Figure 31-2. As other desirable traits are identified, they must be developed through a training program designed to stimulate those traits.

PROJECT CULTURE THROUGH THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE PROJECT

Culture on international projects begins to establish itself during the early stages of the project. The participative process in the development of the work breakdown structure and the project activities network can stimulate the “our project” spirit. It is also then that the first problems arise. Problems at this stage are relatively easy to solve, because enthusiasm on the part of the team members is generally high. The cultural model to be established at this stage is that of strong cooperation of all parties where and when necessary, in the spirit of “all for one, one for all.”

If some individuals at this stage don’t demonstrate efforts toward integration or show uncooperative attitudes, project managers should seriously consider taking them off the project, because if they create problems in blue-sky conditions, they may be impossible to work with when stormy weather appears. On the other hand, emerging team leaders need to be identified and motivated early on in the project.

During the maturing stages of international projects, when the organization is well defined and each unit or department is supposed to take care of its own tasks, the culture tends to become competitive as project groups try to show efficiency in relation to the other groups. Problems mainly arise at this stage because of unbalanced workloads. Some groups may claim to be overworked, while others have little work to do. Strong coordination and regular follow-up meetings are required during these intermediate project stages.

The final stage of the project is particularly difficult in terms of cultural integration. There is less work to do, and people are leaving to go on to other new international projects, often earning more than on “this old and uninteresting project.” At this point, project managers are hard-strapped to maintain the spirit of the remaining group. This is the moment for the managers to show their leadership capabilities to make sure that the final activities of the project are performed with the same efficiency as the previous ones.

FURTHER READING

Casse, Pierre. Training for the Multicultural Manager. Washington, D.C.: SIETAR, 1982.

Halpin, Daniel W. “The International Challenge in Design and Construction.” Construction Business Review Magazine (January–February 1992).

Seaden, George. “The International Transfer of Building.” Construction Business Review Magazine (January–February 1992).

Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations. McGraw Hill, 1997.

Scott C., and D. Jaffe. “How to Link Personal Values with Team Values.” Training and Development, March 1998.

Youker, Robert. “What is Culture in Organizations?” Project Management World Today, March–April 2004.