CHAPTER 6

THE QUIET INFLUENCE OF LISTENING

As I mentioned in the introduction, the Harris Poll research I commissioned found that listening was the most-cited communication behavior of inspirational people. More than half of respondents stated that listening was the most inspiring communication behavior they’ve experienced. Listening is part of this section on being personal because when we’re listened to it feels as though someone is personally investing in us. It signals commitment. Yet, here’s the paradox: Think of how much more time and energy we put into how we transmit information than how we take it in. There’s no comparison. In large part, that’s because we already believe we’re good listeners.

That was certainly the case with me. After deciding to shift my career into leadership coaching about a decade ago, I attended Georgetown University’s certification program. I felt pretty confident going in, figuring it would be worth the time and effort if I personally enjoyed it and fine-tuned a few skills in the process. Just a few hours into the six-month-long program, I was duly humbled. There was a tremendous amount about coaching that I didn’t know. One of my most surprising realizations was that I needed to learn how to listen.

Now, at that point in my career, I had built a business where I prided myself on truly listening and understanding customers. I had managed a talented team of people. Not to mention, I’d spent my career as a communications professional!

And yet, I had a long way to go before I could listen deeply and intuitively, the way that coaches need to with clients. I vividly remember roleplaying with other coaches to practice deep listening, and becoming exhausted.

Having to pay this much attention was clearly something I needed to build muscle around. And so I did—but only after I shifted ingrained habits and spent many months practicing new behaviors. Today I can go into deep listening mode when needed. While not everyone needs to listen like a coach, the methodologies are useful for anyone. After reading this chapter, my hope is that you’ll be able to deepen your listening in ways that inspire others.

Listening as a skill comes up throughout our business and personal lives. Listening signals respect. It shows that we value the speaker. We desperately want our leaders and our teams to listen to us. When we’re in the decisionmaking spot, we are often bombarded with differing viewpoints that require us to listen thoroughly so that we can make the best call. Our customers want to be heard and validated. Our closest friends and family ask for us to listen, and call us out when we don’t.

Psychologist Mark Goulston, author of Just Listen, believes that listening is a primary way of showing others what they’re worth to us. He writes, “It’s not good enough for us to know in our own hearts that we’re valuable; we need to see our worth reflected in the eyes of the people around us.”1

In Inspire Path conversations, attentive listening plays an important role. When people describe inspirational figures in their lives, they say the person made them feel truly listened to—almost as if time stopped for their conversation. Listening at that level conveys an emotional and personal investment. It says: Your opinion is so valuable that I’m going to devote myself not just to hearing you, but to fully understanding you as well.

Deep listening takes more than catching someone else’s words. It can be exhausting, and just plain hard. That’s because in any conversation there’s a whole lot more going on than two people taking turns speaking. To truly listen, you first must be attuned to the larger dynamics at play.

TALK IS CHEAP, LISTENING IS EXPENSIVE

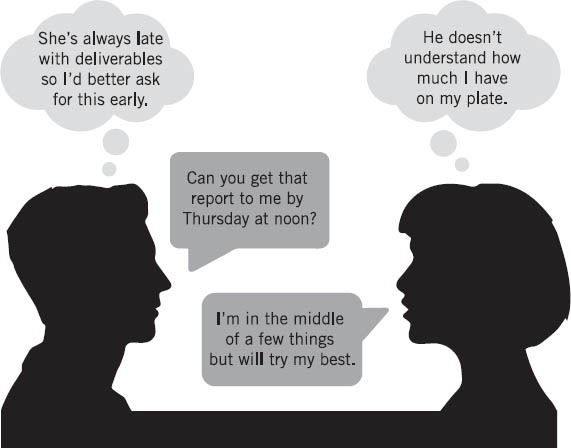

On the surface, a conversation seems straightforward. You talk, I listen. I talk, you listen. We each understand what the other is trying to convey. If only it were that easy there would be no need to write about it. But we know that miscommunications abound. And one of the primary reasons is because in any single conversation there are actually multiple conversations. There’s what you’re saying and I’m saying and what we’re each saying to ourselves. Figure 6.1 illustrates this concept.

In any single conversation there are actually multiple conversations.

Think about it. Every time you open your mouth, there’s a running narrative also going in your head. It starts before you utter your first word, and it runs the entire time you’re talking. Interestingly, if we don’t actively manage it, we pay more attention to our internal conversation than to the one we’re having externally. You notice this in yourself when you miss entire parts of a conversation lost in your own thoughts.

Figure 6.1: Two Separate Conversations at Play

As the graphic illustrates, the words we say and the thoughts we engage in don’t even have to match. In fact, they usually don’t. At best, we speak a subset of the thoughts we’re having. Generally, this is a good thing. Learning to self-censor is an important part of emotional intelligence. However, this thinking/speaking dichotomy gets in the way of listening. It’s practically impossible to pay rapt attention to two conversations at once—especially when they aren’t even the same conversations at their core. You can see that there’s an entirely different conversation happening internally than the words these two talking heads are vocalizing. (This would certainly exacerbate the issues around deliverables.)

It’s nearly impossible to pay rapt attention to two conversations at once—and even harder when they’re two different ones.

Professor Ralph Nichols, considered the “father of the field of listening,” was one of the research pioneers who addressed the impact of our thoughts on listening. Nichols spent forty years studying how people listen and how to improve listening skills. Through his research at the University of Wisconsin, Nichols found that, on the whole, we are very poor listeners.2 Among the findings in his research published with colleague Leonard A. Stevens: After listening to someone speak in a public setting, the average person only remembers 50 percent of what was just heard—regardless of how accurately and carefully the person was trying to listen. After two months, people lose 75 percent of what was said. Keep going and it’s practically as if the conversation never happened.

Research has shown that we retain only 50 percent of what a person has just said, no matter how hard we try to listen.

Nichols identified one of the root causes of our poor listening: the gap between the speed of our words and the pace of our thoughts. The average rate of speech for Americans is 125 words per minute, while our thoughts race considerably faster. To truly listen we actually have to slow down our processing to be attentive to the other person. But that’s not what we usually do. We fill that attention gap by using our minds in other ways, such as evaluating the situation, trying to jump ahead and solve the problem, comparing what they’re saying with our own experience, or taking mental sidetracks that are unrelated to the conversation at hand.

We’ve all been in conversations where we’re speaking and we can see that we’ve lost the other person for a few seconds. Nichols and Stevens argue that we misuse this “spare thinking time.” We divert our attention from the conversation when we should be “listening between the lines”—in other words using the opportunity to hunt for meaning. We can do this by paying attention to speakers’ nonverbal cues and tone, mentally noting their key points, and trying to get to the true heart of the conversation. In other words, by looking beneath the words to the discussion’s actual subtext.

THE SUBTEXT IS SCREAMING IF YOU LISTEN FOR IT

Just as in any conversation there’s an external and an internal dialogue, there’s also a text and a subtext. The text is the words that we’re speaking. The subtext is the underlying meaning. It’s the context of the conversation—our thoughts, history, past interactions, emotions, larger culture, and expectations. When we attempt to listen, we generally focus on the words—or the text. And yes, that’s better than letting our thoughts wander to our errand lists. But all too often we miss the subtext, which gives us a much fuller picture of the situation before us.

Unless we listen for it, probe to understand it and deliberately bring it into the conversation, the subtext sits untouched. It’s the elephant in the room that both parties either ignore or don’t see at all. But it has an oversized bearing on our understanding.

Unless we listen for it, probe to understand it, and deliberately bring it into the conversation, the subtext sits there untouched.

In Figure 6.1, the text is focused on the deliverable. The subtext is that this is a strained relationship where neither the manager’s nor the worker’s needs are being met. If we were to creatively extrapolate this example, the subtext could also be a department that’s understaffed, or a culture that can’t communicate difficult conversations openly. When we include the subtext in our understanding by listening for it, and even probing to find it, then we learn far more than what the words convey.

A recurring situation in my work that demonstrates our failure to listen for and explore subtext involves employee feedback. Here’s a typical scenario: A supervisor or HR leader reaches out to me about working with one of their executives, and I ask what the executive’s development issues are for coaching. I hear a list of concerns, and then I ask, “How much have you shared with the executive?” The leader assures me that the executive has been well informed about both the issues and their criticality.

Then I speak to the executive, who tells me he’s not exactly sure why he’s been referred for coaching. He’s been given some light feedback as part of an annual review, but he’s not sure what he should work on, or if it’s even a priority. He’s open to coaching for his own development, yet he needs clarification on what he should change.

This scenario happens so frequently in coaching it’s practically a cliché. If it occurred once or twice, you might assume that the person giving the feedback isn’t a competent communicator. But it happens over and over again. Clearly something else is going on. This is the delivery of personal, career-impacting feedback. You’d think both parties would pay rapt attention throughout the entire conversation. Yet, two people walk away having dramatically differing views of what just transpired. What gives?

Commonly, two people walk away from a conversation with dramatically different ideas of what just transpired.

Below I’ve sketched out an example lining up the text and subtexts to show what’s really happening in these feedback conversations.

As you can see, Sarah and Brad’s verbal conversation is only a fraction of what’s actually happening. In the text, Sarah is asking Brad to work on collaboration, and he agrees. But in the subtext, Sarah is trying to manage a disruptive bully on her team, placating him enough to change his behavior but keep him motivated on sales. On the other hand, Brad has evidence to suggest that Sarah’s feedback isn’t all that valid. You can imagine why Brad doesn’t “hear” what Sarah is saying, and how they could leave that room with different ideas of what happened.

This idea of text and subtext doesn’t just happen with challenging conversations—it happens with most conversations. That’s why so many conversations miss the point, and why people don’t feel heard. Listening only feels real when we speak about both the text and the subtext. That’s why inspirational communication resonates so personally for us—another person identifies and listens to the full experience that we’re having.

Ignoring the subtext is why so many conversations miss the point, and why people don’t feel heard.

LISTENING TAKES MOST OF OUR TIME AND YET . . .

So listening is a critical skill with multiple moving parts that’s difficult to get right. It’s also rarely focused on as a professional competency. Let me guess that you’ve never been to a training session on listening skills. (If you have, congrats, you’re in a minority.) If we ever learn communication skills, the emphasis is generally on speaking. We attend trainings for public speaking, get mentored on how to speak up in meetings, and take management courses on how to sell a message. It’s as if our success and influence come from only what we say.

We spend far more of our time listening than speaking, yet we rarely get training on listening as a communication skill.

There’s an irony here since we spend far more of our time listening than speaking. Consider your average meeting or conference call. You devote most of the time to listening (or you are supposed to, anyway). Even if you’re presenting in a meeting, there’s likely just as much time allocated to questions and discussion where you’ll also need to listen carefully.

Listening is a desired quality in others. Calling someone a “good listener” is high praise. In their work studying how listening skills shape perception in the workplace, research professors John Haas and Christa Arnold found that listening skills had a significant role in how we assess another’s communication effectiveness.3 According to their analysis, listening behaviors accounted for a full one-third of the characteristics that perceivers use to evaluate a coworker’s overall communication competence. This supports my own experience that we’re just as—or even more—likely to be impactful through our listening as through our speaking.

Some companies do tout a commitment to helping their leaders adopt stronger listening skills. General Electric Chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt said that “humble listening” was one of the top four characteristics in leaders.4 When a leader points to listening as a core competency, that’s a positive sign—and a timely one. With the complexity and speed of change in business, and frankly, our overall globally connected environments, we need people to be open and to listen.

As CEO of the Association for Talent Development Tony Bingham observes, “Technology breaks down the barriers of time and space, and that has contributed to an expectation of connection, accountability, and purpose. Social media has changed the landscape of how we communicate and what we expect from communication.”5

With changing expectations of leaders being felt, every once in a while I’ll see listening incorporated into leadership development or corporate training. The solutions provided are frequently a version of active listening, such as:

![]() Paraphrasing: “I hear you say that . . .”

Paraphrasing: “I hear you say that . . .”

![]() Using I statements vs. You statements: “I feel/believe/want . . .” vs. “You did . . .”

Using I statements vs. You statements: “I feel/believe/want . . .” vs. “You did . . .”

![]() Owning Emotions: “When you say that, I feel . . .”

Owning Emotions: “When you say that, I feel . . .”

These can be good tools to have on hand. There’s certainly nothing wrong with this approach, yet many people feel contrived talking this way. And unfortunately, this type of active listening has made its way into popular culture in the form of parodies and late-night comedy spoofs. Further, when we are so intent on using a certain communication convention, it can take us out of the deep listening mode we’re trying for in the first place.

Instead, I’ve found we can improve our listening more profoundly if we make a shift from how we’re listening to what we’re listening for. In other words, start listening like a coach.

SHIFT YOUR LISTENING TO OPEN YOUR UNDERSTANDING

It may feel like overkill to learn to listen like a coach—after all, most of you aren’t coaches and don’t care to be. Yet, this type of listening can benefit anyone. If you know how to shift your listening, you can go into deep and inspirational listening mode whenever you choose to. You can also recognize when you’re slipping away from it. And if you’re having a meaningful conversation with someone, then you can identify where your listening needs to be.

If you know how to shift your listening, you can go into deep and inspirational listening mode whenever you choose to.

I identify four key shifts in this section that you can make when you’re trying to listen intently. They all require you to move from how you listen to what you’re listening for. Rather than providing techniques, they offer you a way to listen naturally, so you can take in a fuller picture of information and gain a greater understanding.

Let’s also be frank: This type of listening takes more time, and it requires a heavier emotional investment. You have to be prepared for that. Certainly not every conversation requires deep listening. Many are quick exchanges where we don’t need to go much further than the surface text. But in the meaningful conversations where we want to motivate, excite, connect, and inspire, listening is so very valuable.

Focused listening takes more time, and it requires a heavier emotional investment. It’s not for every conversation.

When we want to go into focused listening, we first need to remember the lessons from Section 1 and be present and open-minded. When we’re distracted we can’t absorb the full conversation. This also means timing these conversations to create space. I love this maxim: “The right conversation at the wrong time is the wrong conversation.” Both parties need to be in a place where speaking and listening will be supported. While the conversation doesn’t have to be long, it also can’t be rushed. I’ve yet to meet anyone inspired by a fifteen-second chat in the hallway while hurrying off to another meeting. Listening—and inspiring—takes focused time. But if you know what you’re listening for, that time is well spent.

I’ve outlined four listening shifts that aid important conversations. Of course you can use them for any conversation—any time or anywhere. One listening shift may resonate more than another, or be more appropriate to a particular situation. There’s no right or wrong; these are meant to be guidelines. See what works for you.

LISTENING SHIFT #1: LISTENING FOR FACTS  LISTENING FOR THE WHOLE PERSON

LISTENING FOR THE WHOLE PERSON

Often, when we listen we’re trying to determine the facts. We go into a conversation like a police interrogation, asking for the specifics of the events so we can put it all together for ourselves. If you’re like me, you may even notice that you can’t hear the full situation until you have the facts out on the table. For those of us who like to think systematically and logically, the facts help us orient to the larger situation. We use the facts as a frame.

Here’s where this approach limits listening: When we overfocus on the facts, we push the person talking into the background. We can easily miss the larger picture about how that person relates to the situation, what he is hoping to accomplish, or how he feels about it. Further, we know that facts are rarely pure facts. We remember them through our own filters and biases. How the speaker feels about the details is often more instructive than the details themselves.

When we home in on the facts, we push the person talking into the background.

We’re better listeners if instead of zeroing in on the facts we widen our focus to take in the whole person in front of us. We discuss the facts, but we also listen for how that person explains the situation, what his body language is telling us about his emotional state. When you find yourself trying to uncover the facts, mentally stop yourself. Instead, pay attention to the person talking. Gather as much other data outside of and around the facts as you can to provide a fuller picture. Again, it’s not that the facts don’t matter, it’s that when we focus on them exclusively, we miss important, and actionable, information.

Example: Mentoring conversation

A young professional in your office comes to you for some mentoring and guidance. He’s thinking of looking for a new position inside the company. Instead of asking about whom he’s spoken with, what positions he’s applied for, and when he wants to move, take a step back.

Ask what’s behind this desire to move. Listen to how he talks about what makes him excited, and what zaps his energy. Find out what he wants for himself longer term. The facts will likely fall naturally into the conversation, and as they do, you’ll be better able to provide guidance when you can put them into the context of the whole person in front of you.

LISTENING SHIFT #2: LISTENING FOR TEXT  LISTENING FOR TEXT AND SUBTEXT

LISTENING FOR TEXT AND SUBTEXT

As we outlined earlier in the chapter, there’s a whole lot of subtext going on in most conversations. Sometimes we have an idea what it might be, but we’re not sure, so we don’t mention it. Other times, it goes right by us. Either we choose not to bring it into the conversation because we’re uncomfortable, or we fear the response, or we’re distracted and oblivious.

Conversations where we aren’t brave enough to be real and to say what needs to be said are never inspirational. They’re superficial; they leave both parties lacking. They don’t change behaviors, fix situations, or inspire people. No one feels listened to on an engaging level. They are the conversations after which we say, “Why didn’t I bring that up?” or worse, “That was a waste of time.”

Conversations where we aren’t brave enough to be real and to say what needs to be said are never inspirational.

Learning to listen for subtext in addition to text requires a commitment to being in the moment, and to noticing both the said and the unsaid. It’s paying attention to the clues the other person drops, picking them up, and probing further. It’s asking questions back to gain understanding if we don’t have it. It’s also noting the emotional state of the other person, and bringing it into the conversation. Subtext includes the history and culture that exists around the conversation. Good listeners train their ears to hear that as well as what’s spoken.

When this listening shift happens, real issues that need to be addressed get addressed. Situations are confronted, not glossed over. People listen for the meaning and get to the heart of the issue. They feel seen and heard.

Example: Feedback conversation

Let’s go back to Brad and Sarah from the prior text/subtext exchange. We read what happened when both parties listened for the text: Each took the other’s words at face value and moved on. (And, we can guess that nothing was going to change.) If Sarah were to listen for the subtext, she would have started the conversation more candidly, by letting Brad know that this was a serious issue. She could have listened for his reactions and pointed out that he seemed frustrated by the feedback. She might have asked him what he would be willing to do to change, and fully taken in his responses to gauge his seriousness. And—if he didn’t seem to absorb the feedback—she might have asked him directly if he was committed to working with her.

For his part, Brad could have stated his confusion about what he is actually being evaluated on—his results or his relationships. He could have engaged Sarah on the impact of this feedback to his career, and determined how relevant it actually was.

LISTENING SHIFT #3: LISTENING FOR WHAT YOU NEED  LISTENING FOR WHAT THE OTHER PERSON NEEDS TO SAY

LISTENING FOR WHAT THE OTHER PERSON NEEDS TO SAY

Similar to listening for facts, we can default to listening for what we need from a conversation and miss what the other person needs to say. We are only partially listening to the other person, while working through a checklist in our minds. As we’ve seen, our internal thoughts are often louder and more prioritized than our external conversation.

When we listen this way, our agenda is the only one that matters. We’re filtering out any information that doesn’t conform to what we believe we need to hear. That means we’re missing the other person’s agenda. What’s important to us supersedes what’s important to the speaker. Depending on the conversation, this can negate the whole reason we’re communicating with this person in the first place.

When we listen for what we need, our agenda is the one that matters.

By shifting our listening to what the other person needs to say, we’re opening our own minds to the meaning of the conversation. We’re sharing the agenda; we’re taking in the details we deem worthy, and we’re also noticing the value another places on those details. Letting the other person speak first and set the conversation’s tone may help this. We may need to keep our input to a minimum, or hold it back until the end. Always, it requires us not to cut the other person off, and to encourage full expression.

Example: Buy-in conversation

A colleague comes into your office to seek your buy-in on a project she’s spearheading. You’ve seen this project tried (and fail) before so you want to make sure the situation is different this time. You know exactly what you want to see, so your first instinct is to ask her a series of questions and listen for the responses you want to hear. You’ll direct the dialogue.

By shifting your listening, however, you can withhold judgment and provide an open platform for her to express her ideas and tell you why she’d like you to support her. Rather than proactively asking whether she has covered all the bases, you say “Walk me through your thinking.” You soon learn that your colleague not only covered her bases, but has conceptualized her project entirely differently than the failed approach you’ve seen before. You give her your support.

LISTENING SHIFT #4: LISTENING TO JUDGE  LISTENING OUT OF CURIOSITY

LISTENING OUT OF CURIOSITY

None of us wants to believe that we’re judgmental. Yet, we are. After all, it’s an adaptive behavior that lets us analyze efficiently. Being able to assess our environments, weigh evidence against past experience, and draw swift conclusions allows us to survive and thrive. It aids our functioning in a busy work environment, and may even be why we’re good at what we do. When it comes to listening, however, that same capacity to make snap judgments can hinder our ability to understand—and show understanding of—another person.

This shift requires us to tamp down the analytical, critical part of ourselves in order to stay with the conversation, and show empathy to the other person. We need this shift when we want to learn, rather than just confirm what we already think. It means owning up to the fact that we do try to judge, and in this case, that’s not our objective.

We need to shift to curiosity when we want to learn, rather than just confirm what we already think.

When we listen out of curiosity, we come in with an open mind. We focus attention on what the other person is conveying—the words she chooses, the energy she projects, and the emotions she portrays. We ask questions out of curiosity about what the other person shows us and expresses, rather than simply about what we want to know. We’re not trying to guess or get it right, but to let our curiosity lead the way. A curiosity-driven conversation meanders because we’re learning as we go.

Example: Missed deadline conversation

You have an employee who, in the last few months, has begun to miss deadlines. He’s never had this problem before, and you’ve tried to be patient. But he’s also getting to work late and leaving early. You’re fairly certain he’s checked out and interviewing for another job. You want to verify your hunch so you can prepare.

You’re tempted to go into the conversation with judgmental listening, hunting for any signs that your employee isn’t invested at work. However, to shift your listening into curiosity, you wipe your assumptions before the discussion. Now you aren’t guided by what has happened before with other people. Instead, you go into the conversation genuinely curious to learn what’s happening with this person. You would notice his state of being, what he brings up, and how he approaches the topic. Curious, you’d ask questions such as, “I notice that your engagement seems different—what’s behind that?” or “What should I know about your current work?” or even the simple, “What would you like for me to know?”

Your only objective is to get and stay curious. You can make your judgments and deductions later, but in that moment, you want to learn as much as you can. And you will learn: When people aren’t feeling judged, they are far more self-revealing.

THERE’S NO RIGHT WAY TO LISTEN . . . BUT THERE ARE WRONG WAYS

If you went into this chapter thinking you were already a good listener, I hope this reinforced it. If you were like me, on the other hand, you may have found that listening deeply has more moving parts than you anticipated. The good news is that what we concentrate on gets stronger. If we try to listen better, the trying alone will help us.

I gave you quite a few aspects of listening to consider: managing internal conversations, text versus subtext, and the reasons we don’t listen well. Most of these suggestions boil down to quieting our minds and using the power of our full attention. The shifts may be helpful in certain situations to put new approaches into practice for you. Just naming what you want to do can be beneficial, for instance, “I’m going to go into this conversation with John listening for text and subtext.” When we shift our thinking, we shift our listening.

In the end, there’s no one right way to listen, but there are wrong ways. If we don’t provide a space to listen and to take in the important information, then we may be hearing, but we’re not listening. Even if we don’t recognize when we’re listening poorly, it’s a near certainty that the other party does. When one party doesn’t listen, the other party stops trying to engage.

If we’re in the conversation to inspire someone, we can never underestimate the power of focused listening. I’d be willing to bet that anyone who ever inspired you also listened to you. Sometimes, that’s all it takes.

FROM CHAPTER 6

![]() Deep, focused listening is a key inspirational skill, but it’s harder than it looks. Most people focus on hearing rather than on understanding. It takes effort, but you can become a better listener by understanding the listening environment.

Deep, focused listening is a key inspirational skill, but it’s harder than it looks. Most people focus on hearing rather than on understanding. It takes effort, but you can become a better listener by understanding the listening environment.

![]() Any conversation is actually multiple conversations—the ones we’re stating out loud and the ones we’re having with ourselves. We pay most attention to what’s in our heads, especially when that’s an entirely different conversation than what we’re uttering. This is exacerbated by the fact that people talk far more slowly than they think.

Any conversation is actually multiple conversations—the ones we’re stating out loud and the ones we’re having with ourselves. We pay most attention to what’s in our heads, especially when that’s an entirely different conversation than what we’re uttering. This is exacerbated by the fact that people talk far more slowly than they think.

![]() Most conversations have both a text (what is said) and a subtext (the context that’s not expressed). If we want a conversation to be inspiring and real, we need to bring the subtext into the text.

Most conversations have both a text (what is said) and a subtext (the context that’s not expressed). If we want a conversation to be inspiring and real, we need to bring the subtext into the text.

![]() We spend far more time listening than speaking. Listening has been shown to be a prominent part of how we evaluate one another’s communication effectiveness. Yet, we are rarely trained on listening skills.

We spend far more time listening than speaking. Listening has been shown to be a prominent part of how we evaluate one another’s communication effectiveness. Yet, we are rarely trained on listening skills.

![]() To be a deeper listener, shift your listening from how you’re listening to what you’re listening for. These shifts include listening for the whole person rather than the facts, listening for text and subtext rather than just for text, listening for what the other person needs to say and not what you need to hear, and listening out of curiosity and not to judge.

To be a deeper listener, shift your listening from how you’re listening to what you’re listening for. These shifts include listening for the whole person rather than the facts, listening for text and subtext rather than just for text, listening for what the other person needs to say and not what you need to hear, and listening out of curiosity and not to judge.