Chapter 10

Social Objects

Networks and communities are made up of people, of course, but they are also made of something else: content. In fact, as a customer the first thing you probably notice about any social channel is the content: Is it interesting? Is it useful? Can you rely on it? If you’re creating a social experience for your customers, you want them to answer yes to all of those questions.

But what kind of content do customers want? What’s the best balance between brand-published content versus customer-generated content? What’s the most effective form for content: text, image, video, or something else? To answer those questions, we need to look at social content in broader context. We’ll do that through the powerful concept of social objects.

Chapter contents

- What is a social object?

- Social objects: types and uses

- The future of social objects

What Is a Social Object?

A social object is something that is inherently talkworthy, something around which people will naturally congregate and converse. In the current context of social media—after all, social objects have existed since humans began socializing—a social object forms the link between participants at the center of an online conversation. Social objects anchor the online communities in which conversations take place. Simply put, the social object is the “what” that people talk about.

Social objects can be as small and specific as a blog post, a photo, or a comment. Objects can vary by network or channel: On Twitter it’s usually a text update; on Facebook or Google+ it’s a link; on Pinterest it’s an image. The object might itself be trivial (have you seen this funny cat photo?) or important (please sign my petition!). In either case the act of sharing can be more significant than what is shared. You need look no further than one of these networks to see the unlikely objects that spur vibrant and long-lasting discussion. In a funny way, one lesson seems to be that who, or when, or how social objects circulate is always at least as important as what the object actually is.

Definition: A Social Object is some “thing” we share with others as part of our social media experience on the social web.

Glenn Assheton-Smith, 2009

Social objects don’t have to be small and specific. They can be, well, very large and general. They can be areas of interest, such as the environment, politics, or art. Your business, your industry, your individual products—these can be thought of as social objects too. These types of social objects can also sit at the center of community, drawing people together, not at just one instant but over time.

What are some examples of the kinds of social objects that will pull large groups together? National pastimes and sports like soccer, baseball, cricket, NASCAR, and Formula 1 are just the sorts of activities that tens or hundreds of millions of people around the world will readily associate with and talk about. They’ll form fantasy leagues—clearly a social construct—in order to extend their own level of participation. Fans gather around celebrity sites to share stories and feel a part of the excitement, while retirees readily join up with others in the same life stage in AARP’s online community (www.aarp.org/online_community/) to talk about what the future may hold. Social objects extend to the more ordinary as well—a new mobile phone, a programming language, and a vacation destination can all be viewed as social objects. Oh, and did I mention pets and babies? They’re good candidates too!

A constellation of social objects surrounds every company and every organization. Every customer or customer segment has relevant objects too. To a great extent, our previous comments about defining the relevant topics and themes can be thought of as exercises in mapping the constellation of objects you want in your community or channel.

Channels can often dictate the type of objects to be shared, just by the nature of what they permit or enable. Twitter, for example, is built around short posts, or updates, usually of a timely nature. It’s great for sharing brief nuggets of information or opinion. Nowhere is the impact greater than on media channels: If you’re an online music station like San Francisco–based SomaFM (@somafm) or a radio station like Amsterdam’s KINK FM, you might use Twitter to push your playlists along with news and events to listeners. And, your customers can use these same channels to push a steady stream of updates to you—updates about the experiences they are having with your products or services or your support desk or the staff in your retail outlets. You can use these updates to open a new channel of customer service—as so many companies have, from Comcast to Dell to BSkyB—or you can begin by merely harvesting these insights via a listening tool and using the data to improve products or processes.

Other kinds of social objects lend themselves to the specific purpose of enabling customers to complete a task or mission that they’ve set for themselves. Three examples from France illustrate this well. Hardware and building supply chain Leroy Merlin uses customer-authored product reviews, shown in Figure 10-1, to help customers in the consideration phase of a purchase process to make fact-based decisions on what product to buy.

Figure 10-1: Leroy Merlin product ratings and review

When customers are ready to buy—except perhaps for one or two specific questions—mobile phone service provider Joe Mobile uses question-and-answer pairs, shown in Figure 10-2, derived from past customer interactions to help speed the process.

Figure 10-2: Joe Mobile community

When customers of French grocer Groupe Casino don’t find their favorite products on the shelf of the local store, they can use C’Vous, the company’s ideation community shown in Figure 10-3, to suggest it be added to stock—or perhaps to add their vote to a suggestion already made. Different objects, different purposes, but a common goal—to enable customers to do something they want to get done.

Figure 10-3: Groupe Casino’s C’Vous community

While these three examples illustrate several innovative approaches to the use of the social technology in transactional business processes, your business or organization might have a larger goal. You might aspire to use social channels to help customers fulfill their personal objectives—to improve themselves or their lives or their own businesses. This generally means that you’ll be working with larger social objects—passions, avocations, lifestyles, or causes—and ones that are related to the products or mission of your organization.

A great example of the use of these larger social objects is myFICO, the consumer division of an organization that helps banks and other businesses determine the creditworthiness of individual consumers. If you’ve ever bought a house in the United States, you know what a FICO score is—you generally can’t get a home without it! MyFICO sells products to consumers to help them understand their own credit history and ratings. But the organization, like its parent company, also has an interest in educating consumers on how to use the credit wisely.

Since 2007, social media has played an important role in fulfilling this mission. In 2007, myFICO created an online community, shown in Figure 10-4, for consumers to share experiences and help one another navigate the complexities of credit use in the United States. Thinking of the constellation of social objects around credit, they focused the community on two topics—credit cards and mortgages—in order to target the areas where consumers struggled the most to make good, informed decisions.

Figure 10-4: The myFICO community

The myFICO community has expanded to cover auto loans, student loans, and even business credit. More importantly, it has generated more than a million contributions from individual consumers, both those seeking help and those with help to offer. Often the latter include people who had credit problems in the past and worked to restore their reputation. Their passion is now to help others do the same.

The reward for myFICO? The company finds that community users show a 40 percent higher spend for myFICO’s credit-monitoring and reporting products. It’s no surprise that they buy more—they’re better informed and as a result see the value in the FICO products. But as the keeper of the scores, the company can also see the positive impact that community use has on individual credit scores. Companies talk about measuring the ROI they get from social; FICO can measure the customer’s ROI as well!

Taken together, social objects are essential elements in the design of a social media marketing program built around a sense of community. Social objects are the anchor points for these efforts and as such are the magnets that attract participants and then hold a community together. While it may seem like so much semantics, when compared to the way in which people are connected or to whom they are connected, the social object provides the underlying rationale or motive for being connected at all. In short, without the social object, there is no social.

Take a look at the operational definition of social object at the start of this section again. What it really says is this: People will congregate around the things they are most interested in and will talk about them with others who share that interest. This is what lies at the heart of the Social Web.

By looking at the larger objects—human interests and pursuits—it’s easier to identify and build an SCE strategy that helps the participants in that community be better at the things they love or are interested in. People look to spend time with others like themselves, talking about the things in which they have a shared, common interest or purpose as an enrichment of their own existence. Your challenge is to connect those interests to the things you provide through your business or organization that facilitate their pursuit. Getting this right essentially ensures that the conversations that follow will help you grow your business over the long term.

Why Social Objects Matter

What is it about the Social Web and social media that engages people, and why do they congregate around specific activities or sites? There are actually two answers to this: First, people have in general—and now at least in some manner in most parts of the world—adopted social technologies as a means of keeping in touch. To be sure, it is only a minority of the global population that is involved, for a variety of reasons, but it is also steadily increasing. Sooner or later, the conversations in your markets will flow onto the Social Web. More likely, given that you are reading this, your market is already involved, whether through basic mobile services like SMS—aka “text”—or always-on, always-with-you broadband social applications.

Second, the relationships created via the Social Web have become real for the participants involved. This includes aspects of relationships like identity, reputation, trust, and participation. Do not underestimate this, because it strongly suggests the norms for your own online social conduct and it suggests how powerful the relationships you ultimately build online can actually become.

The combination of the increasingly real-world aspect of social computing—participation in social networks and the engagement in personal and professional life in collaborative, online tasks—along with the emergence of meaningful social objects in that same context creates a social space where real interest flourishes. Creating these experiences and then connecting them to a business objective is an important factor in building a strong and durable social presence online.

Social Objects: Types and Uses

When you begin formulating the plan for your use of social technology in your business, the perspective shifts to that of your customers and stakeholders (or employees, for internal social platforms). What are they interested in? What are the things that they are passionate about or want to know more about? This almost always raises the question of the value of social objects—usually referred to as content but used here with the specific requirement that this content be both rated and shared by and between your customers—as an element of your business plan.

Using Social Objects

Building a presence with social objects is a straightforward—but not necessarily simple—process. The following steps define the process. Each is explained in more detail.

- Identify suitable social objects.

- Create and plan the way you will encourage the development spread (sharing) of these objects.

- Use these objects to build interest and participation in your community specifically and in your social presence in general.

Identify a Social Object

The first step in anchoring your brand, product, or service is sorting out where to actually connect to a preexisting community. The main questions to ask yourself (or your agency or work team, if the overall social strategy is in the hands of a distributed team) are the following:

- What do the people you want to participate with have in common with each other?

- Why are they participating in this activity?

- What do they like to do, and what is it about these activities that they find naturally talkworthy?

- How does your firm or organization fit into the previous points?

- Specifically, how can you improve the experience of the current participants as a result of your being there?

Armed with the answers to the previous questions, you are ready to plan your own presence in that community, and you have the beginnings of how this involvement can be tied to your own business objectives as you simultaneously become a genuine participant in this community.

What are some of the social objects that successful community participation has been built around? Table 10-1 provides a handful to get you started. More will be said about these in the sections that follow.

Table 10-1: Social objects that support communities

| Brand | Social Object | Participant/Brand Connection |

| Dell | Entrepreneurship | Entrepreneurs and small businesses use Dell hardware. |

| Petco, Pet360 | Pets and pet owners | Petco and Pet360 provide everything needed by pets and the people who love them. |

| Pampers | Babies | Babies and diapers go together. |

| Red Bull | Action sports | If two people are competing anywhere on the planet, one is wearing a Red Bull logo. |

Looking at the brands and social objects in Table 10-1, you can see that the main take-away at this point is that each brand has identified for itself an existing social object around which to place itself in an existing social context. This is directly analogous to the process through which a brand is mapped to a core consumer value or articulated business purpose in traditional advertising: Where the advertising anchor points provide a context for communicating what a brand is or what it stands for, the social object provides the context for consumer and stakeholder participation in the activities that are related to the functional aspects of a brand, product, or service.

Create and Plan Your Use of Social Objects

Once you’ve identified a viable social object, the next step is to connect to it. You have choices in how you attach a particular business process to a social object: You may create a service that you offer, for example, that can itself become part of the way your audience pursues its involvement with the social object. Nike+ accomplishes this by connecting runners with its shoes through a service that connects runners with other runners.

Look at the Pampers community, shown in Figure 10-5, as an example. Called Pampers Village, the community allows parents to ask questions and share knowledge about the most common challenges encountered by new parents. You’ll note a feature of this community that has grown more common over the years—the presence of expert content alongside content contributed by customers. In the Pampers Village, a doctor or other relevant professional will respond to the question, and other registered members are free to chime in as well.

Figure 10-5: Pampers Village

Another interesting dimension of the Pampers example is the integration of the community with the loyalty and rewards program. When customers register for the community, they are automatically included in Pampers Gifts to Grow, which entitles members to discounts and other special offers.

Another great example of specific social objects tied to larger social objects is Sephora’s BeautyTalk community. The larger object is beauty and the desire of Sephora’s customers to find the best cosmetics products for their skin type and other attributes and to use those products effectively to enhance their personal attractiveness.

Since the advent of Pinterest, all of us are more aware of the power of image sharing, particularly in helping drive enthusiasm and ultimately commercial activity. Sephora too has embraced images in their on-domain social channels. As you can see in Figures 10-6 and 10-7, customers can choose to experience the community in a style similar to the Facebook feed (Figure 10-6) or as visually appealing grid, à la Pinterest (Figure 10-7).

Figure 10-6: Sephora feed view

Figure 10-7: Sephora image grid view

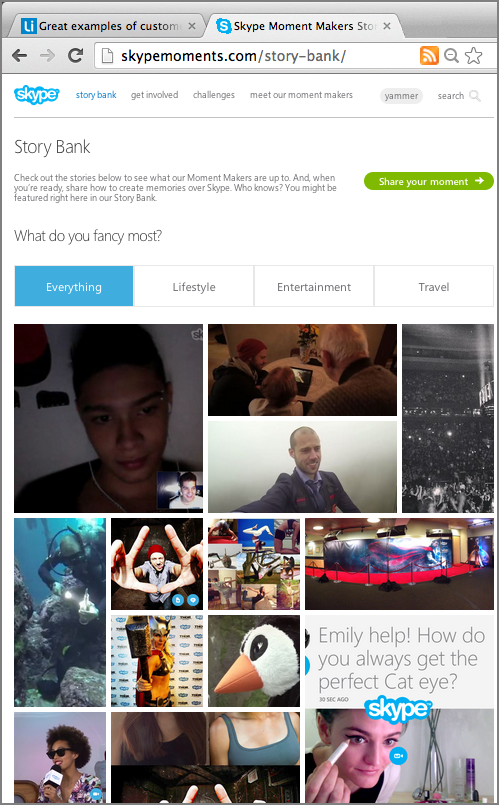

Naturally, where a photo can accurately show appearances, a video can do that and more. In the best case, it can effectively convey emotion. As a breakthrough communication platform, Skype connects millions worldwide. And while a large footprint in a global market is good, that kind of market coverage sets up being seen as a commodity player rather than a unique provider of a specific service. To help defend against the value erosion associated with commoditization, Skype launched a social program around Skype Moments, shown in Figure 10-8, inviting its customers to create and share content that shows how they use Skype uniquely to make little parts of a day that might otherwise go unnoticed stand out. In the process, Skype’s customers are both reminded of and enlisted in sharing what makes Skype special.

Figure 10-8: Skype Moments

Video is, of course, just one example of how social content is expanding beyond the discussion-based interactions that have typified online social content for so many years. Another recent development is the proliferation of customer-populated knowledge repositories. Customer knowledge is increasingly being harvested from other formats—discussion being the primary one—and imported to page-oriented formats like wikis and knowledge bases.

There’s another trend in social objects that is well worth noting. It used to be that almost all the objects shared in social networks—article, videos, and so forth—were objects created by publishers. The commentary around the object was from consumers, but the object itself came from a brand. Today, the objects themselves are increasingly created by consumers. Box-opening videos are a great example: Consumers excited about acquiring a new product film the process of undoing the packaging and examining what’s inside. The same trend is happening with other kinds of content. Today, if you visit the website for Lenovo, you’ll find a great knowledge base of articles about Lenovo laptops and mobile devices. That in itself is not surprising, but look closely: Alongside technical articles written by Lenovo’s experts, you’ll find articles written by customers! Lenovo knows that customers often know as much about its products as employees do, so why not give their knowledge top billing as well?

Peer-created knowledge—not just conversations—is a hot topic in service and support today. One big reason is that putting customer knowledge in article form—not just buried in a discussion thread—is a great way to make that knowledge more accessible. While some customers are eager to learn the ins and outs of a problem by taking part in discussion, others say, “Just give me the answer!” This is particularly true when the requests for help come from Twitter or Facebook. At BSkyB in the UK, peer-generated support content—articles and solutions generated by customers—are used in conjunction with its social media engagement platform to serve this content directly to off-domain customers seeking answers that unbeknownst to them already exist, because they were created by community members.

It’s just conceivable that in the future the home page of customer support communities might look more like a knowledge library than a set of discussions. Look at the Unboxed community at Bestbuy.com, and you’ll see that day has arrived.

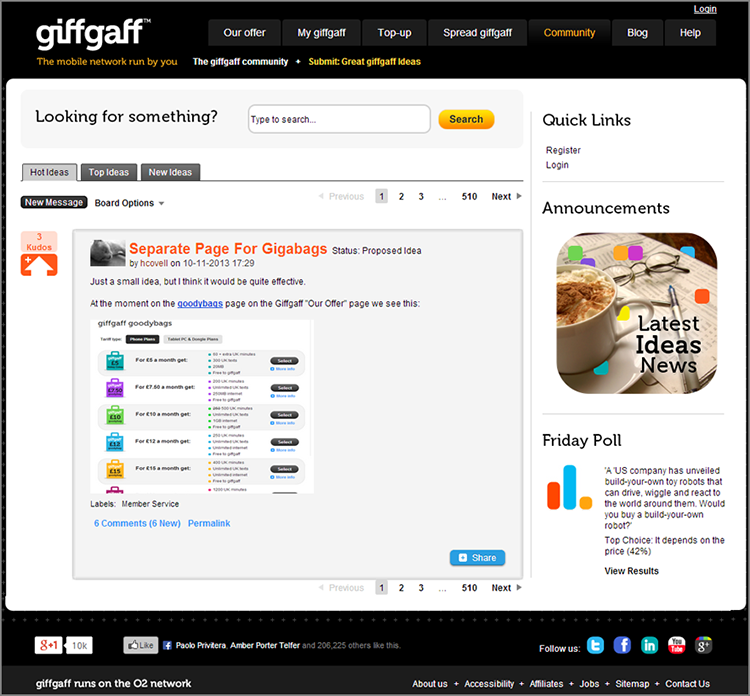

We can’t complete the conversation around social objects without talking about ideas. At giffgaff, a UK-based telecom firm, the company uses peer articles and comments in its ideation (innovation) community as sharable content that is itself directly rated as it is reviewed, allowing giffgaff to easily see which ideas have real traction with customers. The giffgaff innovation forum is shown in Figure 10-9.

Figure 10-9: giffgaff and consumer innovation

You may be thinking that the social object has to be large or that larger brands—perhaps because they are perceived (not always correctly) to have more resources (they have profit and loss pressures, too)—have an easier time. Not true. Social objects come in all sizes, and you can generally find one that applies to just about any business audience segment of interest. Look again at the examples in Table 10-1: businesses focused on pets, babies, and action sports are all powerful social objects. As a result, not only is each of these a social connector—you could easily throw a social event around any one of these topics—they are also perfect alignment points between these businesses and their customers. This is what social objects are all about: They form the common-interest-based connection between your brand, product, or service and your customers, constituents, and employees.

Build Interest and Participation

With your social objects identified and an activation program that connects your business to that activity built around it, attention turns to growing and supporting the community. Think about showing up at a friend’s party. Unless specifically told otherwise, you’d likely bring a small gift to share: an appetizer or dessert, or maybe a bottle of wine if the setting is appropriate. The point is this: This sort of value exchange is recognition that a social gathering among friends is a collective activity, one that is made better as more participants contribute and share.

Your business presence in a community or activity built around a social object works the same way. Since you’re but one of the participants—remember that the activity centers around the social object and not you—your program will generally work better if you are an equal co-contributor to the general well-being of the community and its specific participants.

The result—looking back on the overall process—is that you have created a space for, or joined into, the interests, lifestyles, passions, and causes that matter to your customers and stakeholders. By practicing full disclosure and by taking care to contribute as much or more than you gain, you have successfully anchored your business in what matters to your customers, made things better for them, and created a durable supporting link that ties back to your business.

However you choose to integrate social objects into your social customer experience strategy, building a community based on your brand implies that the brand itself is big enough—or has been made big enough—to anchor the social interactions of that community. For brands that are either sufficiently big themselves (such as GM) or sufficiently novel or talkworthy (such as Cannondale’s commitment to cyclists or Tesla Motors and its electric automobiles), a brand-based community may well be viable. Tesla, GM, and Cannondale all connect to their customers in sufficient ways to support social interaction. Cannondale might build a discussion forum around terrain exploration and riding safety, while Tesla and GM might build around their own insight and innovation programs for future personal transportation using an ideation platform. For business-to-business applications, a company like EDS (now HP Enterprise Services) might build a community of suppliers and contractors, for example, who have a direct stake in the benefits of collaboration aimed at process improvement in the delivery of higher-valued IT services.

In each of these examples, the key is placing the community participant at the center and encouraging interaction between participants that offers a dividend—like learning, insight, and a spreading of the brand presence—to the company or organization. If your strategic plan for a brand-based social community includes this specific provision, you are on solid ground. Note the nuance here: The community (in this case) is built to emphasize a specific aspect of the brand. However, it is the participant, and not the brand, that is at the center of design and the activity that follows.

By thinking about participants as the central element—rather than your brand, product, or service—you avoid one of the biggest mistakes made when approaching social media marketing from a business perspective. That mistake is putting the brand, product, or service at the center of the social effort and then spending money—very often a lot of money—pulling people toward what amounts to a promotional program in the hopes that they will talk about it and maybe even make it go viral. This rarely if ever works over the long term, and even when it does it still fails to drive the sustainable social bonding and engagement behaviors that result in collaboration and ultimately advocacy. Be especially careful of this when implementing a community at the product or service level: focus on the customer experience and the delivery of benefits to customers

Beyond content, larger objects—a whole business, an idea, a passion, a lifestyle, or a cause—can also be effectively tapped as social objects. Found Animals, based in Los Angeles, California (www.foundanimals.org), provides a great example of how a powerful social object—the love of pets and concern for their care—combined with a thought-out presence and community participation come together to create a successful organization. Found Animals became an operating foundation in March 2008, hiring its first employee, Executive Director Aimee Gilbreath, at that same time. The foundation is committed to increasing the rate and quality of pet adoptions, thereby lowering pet euthanasia. To succeed, Found Animals provides financial and business-model support to the Los Angeles municipal animal care facilities with a focus on adoption, spay/neuter programs, microchipping, and licensing. Clearly, the love, care, and concern for animals—of any type, especially companion animals—is a natural, powerful social object around which a community can be created.

Dave Evans spoke with Andrew Barrett, director of marketing for Found Animals, about how social media factored into the overall outreach and awareness programs:

We have several key messages intended for current and future animal adopters and we want our audience to trust us as their partner. These messages include adopt your pet, rather than going to a store, spay/neuter your pet to prevent pet overpopulation, microchip your pet so they can be returned if lost, and license your pet—it’s the law. We are very active on Facebook and Twitter, and these channels have proven excellent tools for us to reach our intended audience and bring awareness to our programs and message in an efficient and popular method. To achieve this, we have an internal, full-time digital-media program coordinator responsible for the strategic and creative development and implementation of our social marketing across all digital channels.

Found Animals maintains an active Facebook presence in addition to its website. Dave asked Andrew about the experience with Facebook:

We have built a relationship with over 7,000 fans on Facebook. We engage them through traditional uses of Facebook and social media: polls, surveys, wall-post discussion, and so on. Many times we use incentives to increase participation, like gift cards for pet-related spending. Currently, we are working to build on our social media success by developing metrics: comparing the amount of participation against the number of new adoptions or current adopters who rely on us as a direct result of our social media program. We will also be measuring the impact of social media on our other initiatives: spay/neuter services, microchipping, and licensing.

Finally, Dave asked Andrew about the growth of Found Animals’ Pet Club and its future plans to continue building its programs around the care and concern for animals:

Let me preface this by saying in most cities once you adopt a pet and leave the animal care facility you’re on your own. Your vet is available by appointment and for a fee. Your friends, family, and neighbors who have pet experience are available as well, when you can get their attention. Generally, there is no single, centralized resource with trusted information and a knowledge base built on personal experiences of thousands of pet owners. The goal of Found Animals and our Pet Club is to serve that need. Through social media, we’ve listened to our community, and they have clearly expressed a desire for a tool like this that is not linked to an exclusive commercial product or line of products or a corporation with commercial goals. Our Pet Club will be a living, breathing, and very personal online experience that will rely on medical and professional experts, as well as the expertise of pet owners like you and me.

What is particularly impressive about Found Animals is the way they have naturally integrated social-media-based marketing and community participation (both online and off) into the operational design and marketing of the foundation. Carrying this further, by listening carefully to their customers and community stakeholders, Found Animals has identified a clear need and a larger, more valued service offering that it is now building into. That’s social business in action.

Lifestyles make great social objects: People naturally tend to associate based on lifestyle choices—values, preferences, care, and concerns—and the ways these personal choices are made visible. Lifestyle is closely related to things like personal identity and culture. The Catalan culture in Spain, the Sikh traditions in India, the Cajun culture of Louisiana, the historical interests that power the Daughters of the American Revolution, or the surf lifestyle (complete with Dick Dale’s Lebanese-inspired surf sound) of California are all at the centers of powerful, compelling, and long-standing communities. Can your brand compete with these, or would it better to join them and bring some unique benefits that connect the participants in communities like these to your business or organization?

Lifestyle-based social objects include action sports—skiing, kart racing, wakeboarding, and kite surfing—along with quilting, cooking, and online gaming. World of Warcraft, for example, is a great example of the kinds of activities that will spawn significant followings. For small businesses—and the businesses and organizations that serve them—there is plenty of interest around the small business ownership lifestyle. Figure 10-10 shows the American Express OPEN Forum, a business community that is built around the needs and interests of small businesses. Lifestyle associations are a great place to start when planning your Social Web presence. They provide natural places for you to participate and, assuming relevance, easy ways for your brand, product, or service to become a valued part of these communities.

Figure 10-10: American Express OPEN Forum

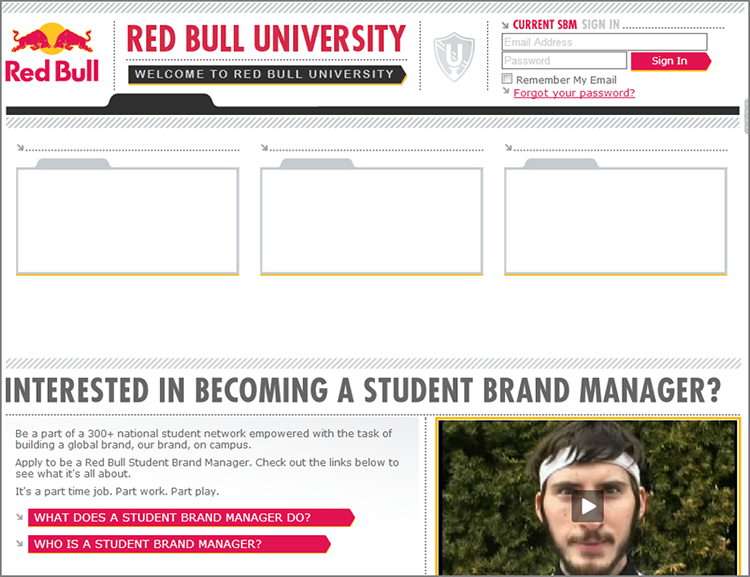

Passions are another rich area when you’re looking for existing social objects. Shown in Figure 10-11, Red Bull University is a community built for enthusiasts interested in taking their passion for action sports to the next level. Beyond the program’s entry point, student brand managers are connected to exchange best practices and tips and to generally assist each other in the development of a variety of Red Bull’s promotional activities, in part by sharing information through the online social channels that form around action sports.

Figure 10-11: Red Bull University

How could you use a program like this in your organization? Could you actually teach your enthusiasts to become advocates? The real insight here is not so much having a brand university—although that’s a pretty innovative step on its own. The big insight is in recognizing that for nearly any fan base, there is a thirst for getting closer to the action, for becoming part of the team. Fans don logo wear for a reason: It’s an act of inclusion. Be sure you consider this when planning your social media program, and more specifically, consider how you can empower your fans to become evangelists.

Right along with passions and lifestyles, causes—such as ending child hunger or advocating the humane treatment of animals—are natural social objects. Not only are causes easy to identify—after all, they generally form around issues that command attention—but the people involved are predisposed to talk about them, driven out of direct, personal interest. This makes cause-related social objects great vehicles for business programs as well as a natural focal point for cause-related organizations, for two reasons.

Number one, by getting involved in a genuine and meaningful way, your business or organization brings more brains, muscle, and capital to the table. Your contributions, along with those of all others involved, make it that much more likely that the ultimate goal of the organization will be met and that the participants in the effort will feel good about the process as a result.

Number two, you are able to create an additional and appreciated connection point between your brand, product, and service and the markets you serve. On this point, a social presence built around a cause-related social object is distinctly different from corporate social responsibility and similar philanthropic programs. Straight-up giving is absolutely appreciated by—and vital to—many cause-based organizations; corporate donations and in-kind contributions help them deliver their services or benefits to society.

Figure 10-12 shows the Tyson Foods Hunger All-Stars program, a cause-based effort that taps the company’s unique capabilities across a number of social channels and additionally highlights the individual contributions of its Hunger All-Stars. This point is a big one: Highlighting the individual contributions—making the participants the stars rather than the brand—is an absolute best practice in social business.

Figure 10-12: Tyson Foods’ Hunger All-Stars

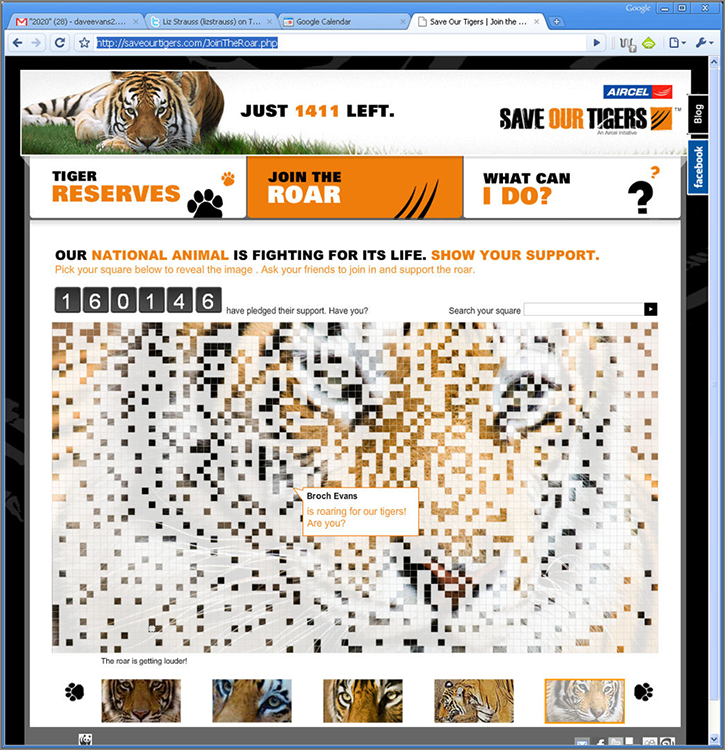

Figure 10-13 shows Aircel’s efforts in raising awareness of the near-extinction of India’s Bengal tigers. The campaign goal, beyond awareness, is in its partnership with the World Wildlife Fund. The program is aimed at moving people to act in support of the protection of the Bengal tiger. In both the Tyson and Aircel programs, the community-building goal is fundamentally the cause and is intended to build on awareness and to move people to action. These programs—whether working in local hunger relief efforts or demanding that existing but overlooked laws regarding tiger poaching are actually upheld—tap the potential in the associated cause-related communities that exist around these social objects.

Figure 10-13: Aircel’s Save Our Tigers

Worth noting in both of these examples is that they aren’t so much examples of marketing alignments with popular issues as they are legitimate efforts to address worthy causes that are aligned with the values and missions of the companies involved and the people in the markets they serve. Tyson feeds families, and so feeding families that are sometimes unable to feed themselves is directly related to its own operations. Aircel describes itself as a pioneer and is clearly part of the next generation of India’s social adopters. That this next generation should also be able to witness first-hand—and not in a zoo, or worse, an encyclopedia—the amazing presence of India’s national symbol fits right into that.

Here’s a great test that you can apply when thinking about building around a cause: Poll 10 random employees in your business as to how some specific cause is connected to your business. If you get nine decent responses, you’re onto something. If not, keep looking (for causes, not employees to quiz).

Finally, one word of caution: If you choose to create a community around a cause, make sure the business is committed to the idea long-term. In general, if your business doesn’t already support the cause in a meaningful way, it’s unlikely to make the kind of long-term commitment to supporting a community and helping it grow.

The Future of Social Objects

The most basic role of the social object is driving conversation. In the business applications discussed previously, the social object brings participants together based on a common interest around which a conversation occurs. It also provides a relevant context for a brand, product, or service.

This clear connection is important: Recall that a basic fact of social media is that in comparison with traditional media, it is harder to interrupt. This differentiator plays out in two ways: First, because it is harder to interrupt the activities of participants directly—like the way you can interrupt a TV program with an ad or an online page view with a pop-up—your activities with regard to your business objectives have to have an obvious relevance. Otherwise, you’ll be ignored (best case) or asked to leave (worst case). The Social Web isn’t a marketing venue, though it is a very powerful marketing platform.

Second, because it is harder to interrupt (if not impossible), your message, your value, and your contributions to the community must be delivered within the existing conversation. In an analogy to TV, think about the difference between product advertising on TV versus product placement within the TV program. In the case of product advertising, there is a clear distinction between the program and the ad. In the case of product placement, the product becomes part of the program.

Trusted Content

Beyond the basic requirements outlines—clear connection to your business and a rallying point that is generally larger than the brand itself—vibrant social strategies are built with or around social objects that are overtly trusted. Simply put, this means that not only do your customers need to find the content that underlies your social programs to be engaging, but they also have to trust it. An easy way to see this is to think about an experience on YouTube, where content engagement is generally high. High engagement does not imply high trust, as time spent watching entertaining but not necessarily useful video content makes clear. To be sure, there is useful and trusted content on YouTube, so the question “what makes content trusted?” is relevant to your formulation of an overall content plan.

In the context of social customer experience, trusted often means contributed by your peers. Survey research by Nielsen in September 2013 found that 84 percent of consumers trust recommendations from friends, and 68 percent trust consumer opinions they see online. By contrast, less than half of consumers trust the most common types of online ads, including those found in social networks, search results, banners, and mobile. This does not mean that consumers generally distrust brands; in fact, they don’t. Company websites are trusted by 68 percent. But it does mean is that in the drive to become smarter consumers, your customers are turning to each other to vet what you claim, to validate what you say. “The best phone for under $100” ought to be evident to those consumers who have actually purchased one or more under-$100 phones. And those comments—immediately discoverable—can be used to validate specific claims. To the extent that comments, ratings, reviews, articles, and so forth are marked as accepted or highly recommended by others, the trust in the content itself increases. By extension, as the trust in the content rises and the alignment with the brand’s own claims is validated, the trust in the brand increases, adding to the value of the SCE program.

This becomes more important as more consumers adopt social technology and increasingly take part in social commerce. You need to be part of the community rather than an interruption. Note that this does not mean hidden and certainly does not mean covert, but rather that you participate in a transparent, disclosed manner. Above all, your participation should appear as a natural element of the surrounding conversation.

SEO: Get Found

With the social object in place, the next objective is building your audience. This means being findable through search. Author Brian Solis, known for his work at the intersection of social media and public relations, has often stressed the importance of using the Social Web and social media as a part of your overall search optimization program. Because the photos, videos, blog posts, and similar content associated with social media can be tagged, described, and linked, they can all be optimized for search. Don’t make the mistake of dismissing this as little more than a tip, trick, or technique to be implemented by search engine optimization (SEO) firms (although a good SEO specialist can really help you here). Instead, step back and consider the larger idea that Brian and others making this same point are conveying: People search for things, and they discover relevant content in this way. If great content—and the community that has been built around it—can’t be found, then that content effectively does not exist. In that case, the community won’t be found.

This much larger view of SEO makes clear that SEO applies to everything you do on the Social Web. Too often SEO is applied in a more narrowly focused application of page optimization or site optimization against a specific set of commerce-related keywords. This works, and it’s better than nothing, but the real gain comes when each piece of social content is optimized in a way that promotes self-discovery and, therefore, discovery of the entire social community. As portals and branded starting pages give way to a search box or a running discussion, how people find things on the Web is changing dramatically. In the portal context or the big, branded community, the assumption is that a preexisting awareness—perhaps driven by advertising—brings people to the content, after which specific items are discovered. For example, I may see a spot on TV that advertises the continuation of the story unfolding in the spot and find at that site lots of interesting discussion around that spot and the associated product or service. More likely, however, people will find that community by searching for the content itself and discovering the community, working backward to the online version of the original TV spot, posted on YouTube.

It’s really important to catch the significance of this. A common approach to promotion typically uses an ad of some type to drive people to a microsite or social presence point where the audience in turn discovers the content that ultimately encourages individuals to join, visit, or otherwise participate. This is not how the increasing use of search engines—everywhere, and increasingly on mobile devices—works. Instead, people search for specific things—often at a very granular level in searches for things like “wakeboard” rather than “action sports watercraft.” With the emergence of ubiquitous search boxes, it is imperative that each single piece of content—each social object in the very narrow sense of the term—be optimized. By optimizing the individual social objects, you greatly increase the likelihood that the larger community will be discovered, since that community is the container for those objects. The “Hands-On” section of this chapter has an exercise that shows you how important this is.

This all gets to the larger point of optimizing social media and social objects in particular. In a world with less interruption, in a medium that is driven by search and powered by direct personal interest along with sharing and recommendations, it is the details (the small items and pieces of content) that are the most desired and hence are the things most likely to searched for and the most likely to be appreciated, shared, and talked about upon discovery. Tags, titles, categories, and other forms of applicable metadata (for example, the description of your company video posted on YouTube) that apply to the content—to the social object—and not just the web page must be keyword rich and must perform as well as search attractors as they do as attention holders. Be aware here: It’s quite common to focus (appropriately) on the content—good content matters, after all—and to completely ignore the tags, titles, and other meta information at the object level and instead focus SEO efforts at the website or page level only. Don’t make this mistake: Work with your SEO team to optimize everything.

Review and Hands-On

Chapter 10 explored the social object in detail. While social objects are in general anything around which a conversation may form (a photo, a short post, or a lifestyle), Chapter 10 focused mostly on the larger social objects (lifestyles, passions, and causes), how they relate to the smaller social objects that customer share online, and the ways in which these larger and smaller objects can be used to encourage conversations around your business or organization.

Review of the Main Points

The main points covered in Chapter 10 are listed here. Review these and develop your own list of social objects around which to plan your social presence:

- Social objects are central to developing trust and trusted content—the customer-approved subset of social and branded content is most valuable.

- Social objects are the center of social activity. Without the social object, no meaningful conversation forms.

- Social objects are often built on lifestyles, passions, and causes, because these are universal areas of commonality and discussion.

- Social objects include talkworthy aspects of your business or organization or unique features of your product or service.

- Social objects, like any other type of online content, should be optimized for search and discoverability. Social objects are very much the connectors between a community and the people who enjoy or find value in being part of it.

Social objects are a building block of online social communities, and as such they are an essential consideration in the development of your social business and social media marketing programs. Built around areas of shared interest, your participation in existing or purpose-built communities gives you a powerful connection point between your business or organization and the people with whom you’d like to build stronger relationships.

Hands-On: Review These Resources

Review each of the following and connect them to your business.

- Look at the work of Jyri Engeström, beginning with this video (http://vimeo.com/4071624) and his blog (www.zengestrom.com/blog).

- Make a list of the social sites you are currently a member of (all of them). Connect each with the social object around which it is built, and then consider how your connection to this object drives (or fails to drive) your participation in that site.

- Visit your own brand or organization website and brand outposts. Is a social object readily identifiable? Does this social object connect your audience to your business?

Hands-On: Apply What You’ve Learned

Apply what you’ve learned in this chapter through the following exercises:

- Create an inventory of communities applicable to your brand, product, or service. Once you’ve compiled it, join a manageable set and understand the interest areas and social norms for each. Develop a plan for how you might integrate your own activities into these communities.

- Using Google, search for a lifestyle, passion, or cause that you are interested in. Note the documents that come back, and review a subset of them. Then do the same content search again but this time select only image results. Review the images and note the number of images that lead you to a social site of some type.

- Define three core social objects for your business or organization around which you could build or enhance your social presence. Create a touchpoint map to help guide your selection.