Chapter 2

The Social Customer

The Social Web connects your organization and its stakeholders—customers, employees, suppliers, and influencers, all of whom have defined new roles for themselves. This chapter explains these new roles in business terms, showing you how to determine which connections matter, who is influencing whom, and where the next great ideas are likely to originate.

Chapter contents:

- Who is the social customer?

- The motives for social interaction

- The customer experience and social CRM

- Customer outreach and influencer relations

Who Is the Social Customer?

In the early days of the Web, the marketing debate centered on the question “who is the Internet user?” Much effort went into characterizing the members of this new segment. They were, it was said, young, tech-savvy, and early adopters. Many wondered if the Web was truly for the mass market.

Today, it’s clear who the Internet user is: It’s everyone.

Likewise, with the arrival of the Social Web, a new and similar debate centers around “who is the social user?” A late 2012 study by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project (http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Social-media-users.aspx) found, predictably, that social network users were more likely to be young, urban, and more educated than the general population. As with Internet users, it’s a fair certainty that those distinctions will fade as the Social Web is knitted more tightly into the business world.

But Social Web users are very different in one important respect: how they behave as customers. It starts with the fact that they are better informed than any previous generation. Google has put the world—its information and to a large extent its population—at their fingertips. But the impact is much broader than that.

Chris Carfi was one of the first to document this shift, way back in 2004, in his “Social Customer Manifesto”:

- I want to have a say.

- I don’t want to do business with idiots.

- I want to know when something is wrong and what you’re going to do to fix it.

- I want to help shape things that I’ll find useful.

- I want to connect with others who are working on similar problems.

- I don’t want to be called by another salesperson. Ever. (Unless they have something useful. Then I want it yesterday.)

- I want to buy things on my schedule, not yours. I don’t care if it’s the end of your quarter.

- I want to know your selling process.

- I want to tell you when you’re screwing up. Conversely, I’m happy to tell you the things that you are doing well. I may even tell you what your competitors are doing.

- I want to do business with companies that act in a transparent and ethical manner.

- I want to know what’s next. We’re in partnership…where should we go?

This is indeed a new kind of customer, looking for a new kind of customer experience. For a company, succeeding in social requires more than a different kind of web presence; it requires a different kind of company.

The Motives for Social Interaction

The “social” in Social Web is really two things: social content and social connections. First, in relation to social content, the Social Web allows users to participate in a discussion, comment on an article, contribute a product review, post a photo or video, or contribute in myriad other ways to the user-generated content (UCG) that makes up the Social Web. If Web 1.0 was written by companies, Web 2.0 is being written every day by individuals. This has transformed the Web in many ways—not the least is that it’s bigger, more varied, and more rapidly changing than ever before. The very architecture of the Web is being transformed by the fact that it now has billions of potential authors. Heard about big data? In a very real sense, you created it!

The term social usually refers less to content and more to people, though in this book we will cover both content and people. And that’s where connections come in. Connections, like content, come in various forms. Someone might favorite a photograph you’ve contributed to the photo-sharing site Flickr—that’s a kind of connection. Someone else might enjoy one of your tweets on Twitter and decide to follow you—that’s a connection too. If that person already knows you—or knows of you and would therefore like to know you—she might even friend you on Facebook. Note that such “friending” is a higher order of connection, since it requires a two-way agreement: two people become friends on Facebook only if both agree. The Social Web is a vast network of connections, even a network of networks: Most people are members of many networks.

As you can tell from these examples, content and connections are deeply intertwined. While people connected online are often connected offline as well—neighbors, co-workers, or relatives—some connections arise purely from content. A research subject quoted in the Journal of Business Research in 2011 describes how this happens:

“I think consumer engagement in the blog starts by somebody needing some information. And so they come, they find the site maybe through Google. They read about it, but they don’t want to read it all, or it’s just easier to come in and ask a question, and they’re welcome to do that. It goes from there. They might stay engaged for a period of time.”

Content often precedes or prompts a connection. And you can’t forget that when people connect, they usually do so for a reason: perhaps to learn something, to share an experience, or to collaborate on a project, but in all cases to achieve something that they can’t achieve alone.

Thus, a great place to start learning about the Social Web and its connection to business is with the basic relationships that are created between participants in social networks and social applications and to then look at the types of interactions between them that follow.

Relationships and interactions between individuals define the social graph—a term of art that means simply who you are (that is, your profile), who you are connected to (for example, your friends or followers), and what you are doing (for example, contributions, actions, status updates). The social graph is to building relationships what ordinary links between websites are to building an information network: These links define the social connections. Without the social graph—and without the profiles and friends, followers, and similar relations that form as a result—online social communities are reduced to task-oriented, self-serve utilities much as a basic website or shopping catalog might present itself in isolation.

A quick way to see this is to visit Yelp. Yelp provides reviews, ratings, venues, and schedule information—all of the things needed to plan an evening or other outing. This is the kind of activity that an individual might do or an individual might do on behalf of a small, known group of friends with a specific personal goal in mind: find a good restaurant and then see a show and so forth. That’s the basic utility that Yelp provides, and by itself it appears to be a site full of social content, but nothing more.

Go one step further, though, and it becomes clear that Yelp is also about people, about social connections. When someone builds a Yelp profile and connects with other Yelpers—that’s what people using Yelp call each other—the transactional service becomes a relationship-driven community. Rather than “What would I like to do this evening?” the question becomes “With whom would I like to do something this evening?” This is a distinctly social motive, and it is the combination of utility value (information and ratings) along with the other Yelpers’ own profile and messages (the social elements) together with whom they are connected to that makes the social aspects of Yelp work. Social—and not purely transactional—tools power Yelp.

By encouraging the development of relationships within a collaborative community—or across functional lines within an organization or between customers and employees of a business—the likelihood of meaningful interaction, of collaboration, is significantly increased. This kind of collaborative, shared experience drives the production and exchange of information (experiences) within a customer community and just as well within an organization. Without connections, there is no sharing of content. It works for Yelp, and it works in business networks connecting manufacturers with suppliers and employees with each other. The key to all of these is building relationships and providing relevant, meaningful opportunities for personal interaction.

A Means to Connect: Friending and Following

Good relationships require three things: a means to connect, a motive to connect, and an environment in which the relationship can grow. In the next sections, starting here with the means to connect, you’ll see how each of these is enabled on the Social Web.

Whether it’s the more intimate connection of friending—the mutually acknowledged linking of profiles within or across defined communities—or the casual connection of a reply to a thread, connections are the cornerstone of the Social Web. Just as in real life, the various relationships that exist between profiles (people) often imply certain aspects of both the nature of the expected interactions and the context for them. Relationships at a club or church are different in context—and therefore in expectation—from relationships in a workplace, for example: When someone elects to follow another on Twitter, there is likewise an expectation of value received in exchange for the follower relationship, all within the context of the network in which this relationship has been established. People create connections to exchange value, at some level, with the others in and through that relationship.

Of course, all connections are not alike. On many sites, people can post content, rate submissions, and similar—but to what end? YouTube is a great example of exactly this sort of content creation and sharing. The result is a highly trafficked site and lots of buzz, but with a depth of social interaction that is less than a brand should expect from a community they create for their customers. Compare this to communities where the majority of sharing involves thoughts, ideas, and conversations and occurs between members who have a true (albeit virtual in many cases) friendship link in place.

Moving from a personal to a business context, connections drive the creation and refinement of knowledge. Collaborative behaviors emerge in environments of linked friends as the recognition of a joint stake or shared outcome becomes evident between participants. Working together—versus alone—almost always produces a better end product. Think about the corporate training exercises that begin with a survival scenario: The group nearly always develops a better solution given the stated scenario (meaning, the group members are more likely to survive!) than do individuals acting alone. And like Carfi’s social customer referenced in the opening of this chapter, members begin to act not just on their own behalf but for the benefit of the community as a whole.

In communities built around shared content, the process of curation (touched on in Chapter 1, “Social Media and Customer Engagement”) and its associated activities such as rating and recommending a photo improve the overall body of content within the community and thereby improve the experience and raise the value of membership. This type of public refinement and informal collaboration results in a stronger shared outcome. The process of curation applies to individuals just as it does to objects like photos. Just as a photo is rated, so are the contributions of a specific community member, providing a basis for the reputation of that member. This sense of shared outcome—of content and contribution driving value and hence reputation—is what you are after when implementing social technologies within the enterprise or when creating an active, lasting customer or stakeholder community that wraps around it.

Ultimately, the acts of friending, following, and similar formally declared forms of online social connections support and encourage the relationships that bond the community and transform it into an organically evolving social entity. As these relationships are put in place, it is important that the participants in the community become more committed to the care and well-being of the community. Plenty of social networking services have failed even though lots of members had lots of friends. There needs to be an activity or core purpose for participants to encourage them to engage in peer-to-peer interaction. Chapter 10, “Social Objects,” Chapter 11, “The Social Graph,” and Chapter 12, “Social Applications,” offer in-depth discussions on how to ensure that these essential relationships form.

An Environment for Connection: Moderation

When talking about communities, networks, and other social sites, there’s a fundamentally important connection: the connection between the individual and the community or network as a whole, or more simply membership. In general, to contribute to a community or network you must become a member. Membership typically involves a registration process in which you contribute information about yourself, and you also agree to the rules that have been defined for that community or network.

The preceding discussion of relationships and interactions and their importance in the development of a strong sense of shared purpose within a community left aside the question of how the social norms or rules of etiquette are established and maintained within a community. Cyberbullying, flame wars, and the general bashing of newbies clearly work at cross-purposes with developing a vibrant online community. In the design of any social interaction—be it as simple as posting on Twitter or as complex as driving innovation and collaboration in an expert community—the policies that define and govern the conduct of participants, also known as Terms of Service, are of utmost importance.

By the way, almost every website has Terms of Use, but don’t get confused—these aren’t Terms of Service. Terms of Use usually govern the use of content found on the site. Terms of Service, by contrast, come into play when you register to use a service, not just read content. Communities and networks are services, ergo, Terms of Service.

Typically, the Terms of Service provide for the following, each of which contributes directly to the overall health of a collaborative community:

- An expectation of participation, perhaps managed through a reputation system that rewards more frequent and higher-quality contributions

- A requirement that participants stay on topic within any specific discussion so that the discussion remains valuable to the larger community and so that the topics covered are easily found again at a later date

- The prohibition of any form of bullying, use of unacceptable (e.g., hate) speech, posting of spam, and similar behaviors that are counterproductive within a typical business (or related) community

Always read the Terms of Service for network and communities you use. Not only will they explain your obligations in using these sites, they will also give you a good idea of what you should include when creating your own terms of Service.

Of course, successful networks and communities don’t stop at writing good rules: They think hard and creatively about the question “what will we do when the rules aren’t followed?”

It is the function of moderation that takes over when rules aren’t followed: Moderators, among other duties, watch for unexpected issues or problems that require some sort of review or escalation. At a basic level, moderation enforces the Terms of Service by warning members about inappropriate posting, language, or behavior. Moderation provides a sense of comfort for newer members who may be unfamiliar with more subtle rules or expectations that exist within the community. Moderation is typically guided by a brief document called a Moderation Guideline.

While members themselves typically do not see this document, your social agents, moderators, or others charged with maintaining your community use it to guide every step of the moderation process, from identifying issues to warning members. Moderation Guidelines, Terms of Service (governing external communities—for example, a customer or supplier community), and social computing policies (governing internal use of social technology—for example, by company employees) together provide an organizational safeguard when implementing social media and social technology programs. Terms, guidelines, policies, and more are all part of an effective social effort.

Before leaving moderation—and do visit Jake McKee’s resources (see sidebar “Community Moderation: Best Practices”) for further discussion on moderation best practices—there’s one last point with regard to ensuring community health: Moderation provides an important relief valve for seasoned members. By guiding conversations in the proper course and keeping discussions on track, skilled moderators actually make it easier (and more pleasant) for the experts in a community to stay engaged and to continue contributing in ways that benefit everyone. This too contributes to the overall development of effective social community programs.

A Motive for Connection: Reputation

In this final section you’ll learn about the establishment of “motive”—about why people want to connect.

Curation, touched on previously, is often presented in the context of content, rating a photo or commenting on or scoring an article. As noted, curation also occurs between community participants: In the context of the community participants, curation occurs between members with regard to contributions and behavior. Members are voted up and down or otherwise ranked according to the relative value of the quality of their contributions and impact or value of their participation as individual community members. This is directly analogous to the way personal reputations are built (and sometimes destroyed) in real life.

Reputation systems—formalized manifestations of the curation process when applied to profiles and the acts of the people represented by them—are essential components of any brand community or network. Without them, all sorts of negative behaviors emerge, ranging from unreliable posts being taken as fact (bad enough) to rampant bullying and abuse (which will kill a community outright).

Reputation systems and content curation work together to help you manage and grow your social presence. Unlike your ad or public relations (PR) campaign, which you can start, stop, and change at will, on the Social Web it’s generally not your conversation in the first place, though you may well be a part of it. Rather, the conversation belongs to the collective, which includes you but is typically not yours alone.

On the Social Web the actual customer experiences, combined with your participation and response to them, drive the conversations and hence provide the key to managing them. Management in the social context depends on authority—manifested through reputation—and that authority has to be earned rather than assumed. Reputation, which applies at the individual level just as it does to the brand or organization, accrues over time in direct response to the contributions of specific members associated with that brand or organization. A declaration of “guru” means relatively little without the collective nod of the community as a whole.

Reputation management works on the simple premise of elevating participants who behave in ways that strengthen the community and by discouraging the behaviors that work against community interests. Posting, replying, offering answers or tips, completing a personal profile, and similar are all behaviors that typically result in elevated reputations. HP’s Support Forum ranking structure, shown in Figure 2-1, is an excellent structure that is patterned on the hierarchy of a university. Each level is based on not just one kind of activity but a range of activities organized in a formula. Participation is rewarded, but quality is emphasized. Members can clearly see where they rank in relation to the overall hierarchy.

Figure 2-1: HP Support Forum ranking structure

The importance of the reputation system in a social community cannot be overstated. Absent reputation management, individual participants are essentially left on their own to assess their own value and that of the participants around them, which rarely leads to a satisfying experience. It is this satisfaction that is at the root of the motive for connecting in the first place! Simply put, people do what people like to do; they do things that feel good.

Beyond the work of a skilled moderator and a well-designed reputation system, tips and guidelines should be presented clearly. Helping your community members do the right thing on their own—rather than simply telling them to do it—is a direct benefit of a reputation management system. Rather than prescriptive rules, a dynamic reputation management system provides feedback that guides members—in the moment and in the context of specific activities—in the direction that supports the collective need of the community.

When implementing any collaborative social program, pay specific attention to the design of the reputation management system. Technical help communities like HP’s Support Forum or Stack Overflow (http://meta.stackoverflow.com/help/badges) are well worth studying as examples of how reputation systems may be implemented. Reputation systems can incorporate badges, medals, or points in addition to ranks and make contribution rewarding and also fun. Social customer experience platforms like Lithium Technologies allow you to reward and incent the kinds of participation that helps communities grow and thrive.

The Customer Experience and Social CRM

As we noted in Chapter 1, CRM was envisioned as a data-driven understructure to power great customer interactions, particularly in the sales cycle. Based on historical transactions, insights into what a customer may need next, or when a particular customer may be ready for an upsell, offers are generated based on past data and the known patterns of purchase or use that exist across the entire customer base.

In a social world, however, guesses based on past transactions aren’t enough. Customers are now expressing their wants and needs directly, online. When CRM is adapted to support this new customer role, it is called Social CRM, or SCRM for short. Think here about the social feedback cycle and the role of a brand ambassador, or an advocacy program that plays out in social media. In each of these, there is a specific development process—from tire kicker to car owner to loyal customer to brand advocate—that can be understood in terms of available behavioral data. Posts on social sites, collected through social analytics tools, for example, can provide real clues as to the likelihood of building brand advocates or spawning brand detractors at any given moment.

This new customer role can be effectively understood and managed by borrowing some of the ideas and practices of CRM and then weaving into them the essential social concepts of shared outcomes, influencer and expert identification, and general treatment of the marketplace as a social community.

On the Social Web, individuals participate for many reasons: to learn, to have fun, to gather facts or answers that help them accomplish their own goals. As a social customer, motivations include becoming smarter about a favorite product or service, contributing to the improvement of loved brands or companies, or earning recognition for knowledge or abilities. In the course of participating, customers share their experiences, opinions, ideas, aspirations, and intentions. This information can be used to design better products, understand unmet needs, or even identify customers who should receive discounts or incentives. When SCRM extends from gathering data and shaping interactions to transforming business processes and creating customer experiences, we’re in the realm of social customer experience management (SCEM).

The Role of Influence

Both SCRM and SCEM draw on the interactions between people, on relationship management and influence, and on how conversations relevant to the business can be used to drive sales. But what makes one particular reviewer more influential than another?

For example, a potential customer looking at a review is actually looking at the net result of the business process that resulted in an individual customer being moved to write this review. If you can understand the business decisions that drove the content of the review—your store opening at 9 a.m. instead of 8 a.m., your return policy requiring an original receipt, or choosing to offer gluten-free dining options—from the perspective of the individual who actually wrote the review, you can sort out the real business impact of your operational decisions in a social context. Simply put, knowing who is talking about you and why—and being able to relate this to your specific business decisions—is fundamental to building brand advocates on the Social Web. Social CRM—data driven and focused on the feedback cycle—extends across your entire business and wraps the entire customer experience, including external influencers. An understanding of the present role of the customer in your business, along with the role of influencers and a resulting ability to connect with them just as with customers, is what makes social CRM powerful.

Very important—and a big insight into what separates social customer experience management from social media marketing—is taking note that SCEM is often used by operations in addition to informing marketing about customer trends and business issues. As used here, operations refers to the departments and functions inside your organization that deliver the actual customer experiences. Beyond product promotion or brand messaging, SCEM data and related analytical tools are often used in customer support to estimate phone unit staffing levels, in product management to spot potential warranty issues, or in product design to identify potential innovations. SCEM is therefore an approach to business that formally recognizes the role of the customer and external influencers as a key in understanding and managing conversations around the brand, product, or service. If the reference to conversations seems to narrow the definition, consider this: The conversation in the contemporary business context is a holistic, digital artifact that captures and conveys the sum total of what your firm or organization has delivered. Markets are conversations, right?

Kira Wampler, formerly of Intuit where social brand building is a highly refined practice, provides great insight into the new role of the customer: She points out that most organizations know ahead of time where their next “Dell Hell” (the online forum that led to Dell’s breakthrough response and adoption of social technology) or “United Breaks Guitars” is going to come from, so why not be proactive and fix things ahead of time? Kira recommends a basic set of questions and activities:

- Audit existing voice-of-customer channels: How many are in use, what is being said, and what is the process for analyzing, responding, addressing, and closing the loop with a solution?

- Map the customers’ end-to-end experiences: Understand in detail each step that a customer undertakes when doing specific tasks that relate to your product or service. Create cross-functional teams to relate what you learn to each point in your process that impacts the customer experience at that point.

- Overlay the moments of truth with a feedback channel audit: Where are the gaps? Where do the channels overlap? What feedback do you have that shows how you are performing at these points?

- Establish a baseline of customer experience and priorities to improve: Based on these, align efforts with your business objectives and set out a plan.

- Establish a regular process for reporting: Use the associated metrics for each step in the process along with your plan to keep your larger (cross-functional) team updated. “No surprises” is the best surprise.

Put these ideas together and you have the basic value proposition for social CRM, in the context of a new role for the customer, in a participant-driven business: By understanding who among your customers is influential, by noting who is at the center of a specific conversation, and by developing relationships with these people, you create the opportunity to more deeply understand why they feel—positively or negatively—the way they do. You can use this information in a forward-looking (proactive) rather than reactive manner to drive innovation and to ultimately shape the conversations in ways that benefit rather than hinder your business.

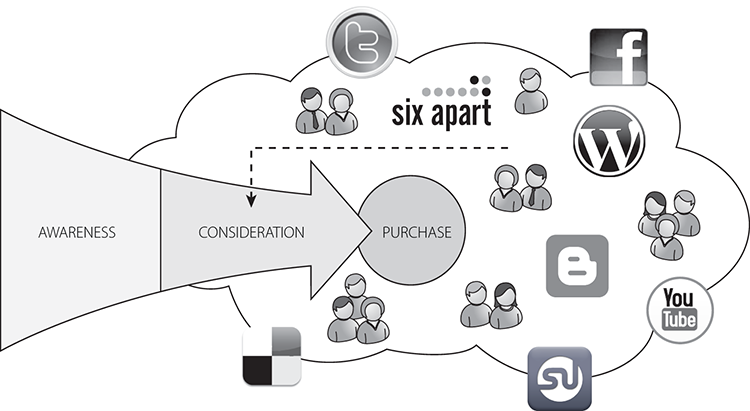

Looking at Figure 2-2, you can see that the product or service experience creates a conversation, one that is often directed or intended for a specific audience and that often exposes or suggests an opportunity for innovation. This is the new role of the customer, expressed through its impact via the traditional CRM process, integrated now with a social component.

Figure 2-2: The new customer influence path

The Social Graph

Just as you are able to track your communication with an existing customer through the relationship life cycle, you can track customers and other influencers through that same relationship when they create content and converse on the Social Web. This can be very enlightening and is really useful when pulled into the product design process.

You can apply this same discipline internally, too, and connect customers and external influencers to your employees, to the customer service manager, to brand managers, and to others. Once connected, your customers and employees can bond further and move toward collaboration. Collaboration drives customer-centric product and service innovation and leads to the highest forms of engagement with your customers.

How do you encourage collaboration? Start with your data gathered through customer registration or collected as a result of online social engagement. You can use this to understand what your current and prior customers are saying about your product or service or about your brand, firm, or organization in the context of actual purchases and experiences. You can then extend this effort to bring the views of external influencers—bloggers, for example, who may not be customers—into your business decision process as well. All of this adds up to information you can use to drive change and innovation just as HP, United, Starbucks, Dell, and others are doing.

How do you integrate influencers into the way you do business? One example is what companies are doing with a tool called BuzzStream. BuzzStream helps you connect with, and manage your relationship with, the influencers in your marketspace. BuzzStream contains basic social CRM and social graph capabilities centered on influencer identification and contact management. Figure 2-3 shows the BuzzStream console and the social linkages identified for a typical influencer and the corresponding profile of interest. Scanning the figure, note that a basic Twitter listening tool was used to spot an interesting post and that this information was then used to look in further detail via BuzzStream at the person who created that post. The result was a specific action (sending a book) in response to that post.

Figure 2-3: BuzzStream and the social graph

BuzzStream and similar tools include influencer dashboards that allow the easy monitoring of conversations based on keywords and the conversion of source data in much the same way as basic social web listening tools work. With influencer-monitoring tools like BuzzStream, the profiles and links of people directly contributing to the conversation you are following are converted into contacts in an influencer database that can be managed alongside your other customer data. Note that BuzzStream provides one component of a larger social CRM effort: Combined with your business data, deeper social analytics, and an internal collaboration platform, BuzzStream’s contact information provides an easy way to manage subsequent conversations with the influencers around your brand, product, or service as you track issues, look for opportunities, and introduce innovations driven in part by these same conversations.

At the heart of tools like BuzzStream is the social graph. Social influence and social CRM tools work by crawling the personal and profile links in your online conversations to find information about the source of the conversation in much the same way as a searchbot crawls page links to find related or supporting content. Starting with a comment or a blog post, BuzzStream looks for a reference to a website or email or Twitter handle that may be present in or near that post. As it finds contact information, the social graph crawler will organize and return potential or contact points.

As these contact points are discovered, a list of potential links and identities are grouped together and presented through the dashboard. As a human (yes, we are still needed!) you can review this information and pick out the bits that actually seem related. Then, click a button and create your influencer contact. A typical contact may have a profile name, a Twitter handle, and perhaps an email address or phone number. Over time you’ll add to it, as your actual relationships with these influencers develop. Once this contact is created, its tweets, emails, or similar will be logged, just as with a traditional CRM system. You can then build and manage your relationship with these influencers just as you would any other contacts.

Engaging the Social Customer: Two Cases

Let’s look at two cases in order to understand where and how social CRM and similar concepts can be applied in business. Note in these examples that breakthrough ideas are often the product of small teams, focused on customer issues. Decades ago, famed GE CEO Jack Welch used to say that every successful company should have a small group of people working on the question “what would our business look like if we blew it up and started from scratch?” What he didn’t know was that, one day, that small group of people would be your customers!

Barclaycard Ring

If customer insights can help you improve your products and services, why not ask customers to help you create products in the first place? That was the inspiration for Barclaycard Ring, a new credit card product based on strong collaboration between the company and its customers.

The effort was founded on three core beliefs, articulated by Barclay’s as follows:

- Customers deserve a simple credit card that’s also a great deal.

- The bank needs customers’ ongoing feedback to make Barclaycard Ring even better.

- Members should have a real say in how their credit card evolves over time.

These were radical ideas—particularly in an era when trust in banks and financial services companies was at an all-time low. Would customers respond?

Remember the “Social Customer Manifesto”? If so, you’ll know that the answer was a resounding yes. And the results weren’t just reflected in the number of registered members or volume of participation. Barclaycard found that the new card has a higher retention rate than traditional cards as well. Retention matters, because attracting new customers is expensive, and all (other) customers benefit from the reduced churn because the underlying cost of this card—and hence the cost to customers—is lower. Products that are built through direct collaboration typically have another benefit as well: fewer complaints. In the case of the Barclaycard Ring, the new card generates half as many complaints as a traditional credit card product, which further generates cost savings. The result for customers? An attractive annual percentage rate and the absence of fees that otherwise make customers crazy.

So, the business benefits are clear, but what keeps customers engaged? To some extent, it’s the same force that united the old-time credit union: Barclaycard Ring customers are part of a community, in other words, the environment in which connection can occur. On the Social Web, participation can be recognized and rewarded in visible ways. The Barclaycard Ring community has a reputation system that reflects many dimensions of a member’s interactions with the company and the community. To use the popular term, the community is gamified: points are earned for helping others with useful information, and badges are awarded for taking positive actions such as paying on time and going paperless. This is the blend of social CRM and social customer experience management in action: the marriage of business systems and social systems to create a holistic social customer experience.

In 2012, Barclaycard’s success was recognized with the Forrester Business to Consumer Groundswell Award.

For more information on Barclaycard Ring, see the following:

http://player.vimeo.com/video/70438563

Autodesk

It might seem from what we’ve discussed that social is all about consumer-facing businesses (B2C) and not so much concerned with the world of business-to-business (B2B). In practice, social customer experience management is equally applicable in business-to-business.

A great example is the customer community at Autodesk. Autodesk makes the software that designs and shapes much of the world around you. Their best-known product, AutoCAD, is the world’s leading 3D design and engineering software. But when Autodesk helped launch the computer-aided design revolution in the 1980s, it was a small group of engineers who foresaw the need to move from pencil-and-paper design to CAD tools.

The AutoCAD movement grew through the use of early social tools: newsgroups and commercial online services like CompuServe. That makes Autodesk’s community one of the oldest continuous social efforts in the world of business.

As a pioneering and innovative firm, Autodesk was also one of the first companies to see the power of marrying social technologies to CRM systems: providing its customers with the means to collaborate (social) and the business platform (CRM) to capture, organize, and facilitate the development of relationship. CRM is of particular importance in business-to-business, where the lifetime value of the customer is high and customers expect a high-touch experience. With a mature online social effort Autodesk asked the question “how can we create a social customer experience that has the same qualities as the 1:1 relationship we enjoy with our customers?”

To serve a customer well, you first need to understand who that customer is. To do this, the CRM connection is critical. CRM systems contain information like customer type, purchase history, and current service subscriptions. Social systems contain rich customer-contributed content, but often it’s associated with little more than an email address. Clearly, the two needed to be combined, but how?

By linking their Salesforce CRM system to their Lithium social platform, Autodesk creates an experience that is specific to that customer. A simple example: some Autodesk customers have support contracts that entitle them to direct support and advice from Autodesk engineers and support professionals. With the CRM integration those customers—even when participating in the general support forums—can be identified and provided with specific assistance according to the provisions of their contracts. Customers who have asked questions in the community yet have not received answers may escalate their question directly to an Autodesk engineer. Even better, unanswered questions from support subscribers can be automatically escalated if they remain unanswered for 24 hours. The combined power of customer data (CRM) and social data (from the social customer experience platform) enables these types of meaningful and rewarding business processes. The result? A systematic development of brand advocates.

For more information on Autodesk’s efforts, read the Gartner Group case study written by Michael Moaz:

www.lithium.com/customer-stories/autodesk

Or, just search the Web for “lithium autodesk case study.”

Outreach and Influencer Relations

The prior sections covered the role of the customer as an influencer and the impact of this influence on business through disciplines like CRM. You saw how social CRM can fit into your organization’s business intelligence and relationship management programs and how it ties the response-driven foundation of traditional CRM to the Social Web’s customer experience management process.

This section focuses on very specific conversation makers: your customers who—through their own efforts in blogs, forums, and social networks—effectively speak with authority. These customers may cover your particular market as a part of their profession or, as in the case of passionate hobbyists, purely out of interest in what you do or what you make. Because these customers speak with authority, they play a nontrivial role in landing your product or service into shopping carts.

Influencer Relations

Influencer relations extend the basics of customer outreach, taking your outreach as it relates to customer relationship management to the individual level. In an early AdWeek post covering the release of Accenture’s 2010 Global Content Study, columnist Marco Vernocchi summarized one of the key findings this way:

Target individuals, not audiences. The days of thinking about audiences in broadly defined demographic buckets are over. As consumers abandon analog and consume more and more content on digital, connected platforms, media companies have been handed an opportunity—an obligation, even—to engage with customers as never before.

Almost five years on, engagement of customers across social channels is just now becoming a reality. For large brands, the task is daunting: To respond to the thousands of posts created each day that mention these brands, an efficient process built around capable engagement tools is required. Note that while you do not have to physically meet and greet every single customer, you do need a way to identify those customers for whom a response is required given your business objectives. Individual customer engagement pushes you beyond listening and analyzing broad trends and sentiment into engagement platforms that would be more recognizable in a call center than in a marketing group.

Individual engagement is the challenge now: without it, it’s nearly impossible to support the collaborative processes your customers crave. This ability to scale across tens or hundreds of thousands of individual customers is perhaps the most important requirement as you plan your overall social customer experience management program. How big is big? In its first year using a true engagement platform—Lithium Social Web—DISH Network engaged with customers, parsing, routing, prioritizing, and responding to over 1,000,000 separate posts.

Why such massive scale? The Social Web is open to all comers: There is a place for everyone and therefore the requirement to engage with large numbers of customers as individuals. Today’s one-off customer interaction may just turn someone into tomorrow’s evangelist and may well create your next round of enthusiastic influencers. Your social customer experience program combined with an engagement platform will identify and help solidify relationships at a near-grassroots level.

Here’s why: Aside from reaching and building relationships with people who may be influential to large groups of people important to you—a customer-turned-blogger with a following, a customer viewed as an industry expert, or similar—consumers are increasingly making their purchase decisions based on information, tips, and recommendations from people like themselves. Take a look at the sidebar on the Edelman Trust Barometer, and download that free report. The Trust Barometer, itself from a trusted source, makes a very convincing case for social media listening programs and for taking the step to individual engagement, thereby giving you the edge and the insight you need to position your business for long-term success.

Influencer Relations: A Representative Case

Following is a quick case study on influencer outreach. In this case the primary challenge was assembling a cross section of influencers from a very large and distributed set of individuals who are each an influencer of relatively small numbers of people but in total add up and therefore possess a significant voice.

McDonald’s Family Arches

Fast-food giant McDonald’s has long been the subject of attention for the nutritional value of its food. In the media, the reporting on the subject is often harsh and sometimes, in McDonald’s view, unfair. A wider range of opinion is found on the Social Web, where customers themselves share the practical, day-to-day needs that are served by low-cost, well-prepared convenience foods.

Recognizing the value of the Social Web in shaping opinion, McDonald’s in 2010 reached out to women who were blogging on the subject of food, families, and nutrition with an interesting proposal: Would they be interested in participating in a community where they could discuss these topics with others like themselves? The results would help McDonald’s better understand the needs and opinions of these increasingly influential individuals and help those individuals be better informed about the subjects they care about. A typical reaction to McDonald’s “Family Arches” is shown in Figure 2-4.

Figure 2-4: Reactions to Family Arches

Why would people volunteer time and effort in a program like McDonald’s Family Arches? Participants saw benefits—a motive—including the following:

- The opportunity to share questions and feedback with McDonald’s

- The chance to earn cool swag from McDonald’s and invitations to exclusive events

- Access to exclusive info straight from McDonald’s leaders and executives

- Connections with trendsetters, creative thinkers, and influential parents from around the country

- The opportunity to help build and shape the community from the ground up

The activities aren’t just online: The creative moms who author the Mommy Warriors blog (www.mommywarriors.com/), for example, were invited to attend a star-studded product launch in Hollywood, where they became some of the first members of the public to sample the new Chicken McBites product. Jokingly wondering whether two tired moms could stay awake for a 9 p.m. event, they ended up having a great time—and writing about it, of course, online: “To all the folks at McDonald’s and the Chicken McBites Brand, thanks for a great evening, you made two moms feel young again!”

Take a larger view of the Family Arches program: Beyond the celebrity events, the shared purpose of the program, for members and for the company, is a serious one. In an era of increasing attention to health, food quality, and significant issues like obesity, the need for informed dialogue is more important than ever. A partnership between McDonald’s and caring moms is making it happen. If you’re a mom and a blogger, join in!

Review and Hands-On

This chapter defines the new role of customers and stakeholders—the recipients of the experiences associated with the product or service you are providing—and then connects those customers and stakeholders into your business. Social CRM and social customer experience management are the larger operational and analytical processes that wrap all of this and help you understand how to respond in a dynamic, conversation-driven marketplace.

Review of the Main Points

This chapter explored the more participative role of the customer and the tools that support the new expectation of an opportunity to talk back to the brand and shape future experiences and interactions. In particular, this chapter covered the following:

- Social relationships develop when three elements are present: a means to connect, a motive to connect, and an environment in which a relationship can grow.

- Social CRM is a business philosophy. It refers to the tools and technologies used to connect your customers and influencers into the forward-looking, collaborative processes that will shape your business or organization as you move forward.

- Social customer experience management (SCEM) is about engagement and innovation, getting at “what’s next” from your customers’ point of view. SCEM is most useful when applied at the business (operational) level.

- Influential customer engagement programs that capture, prioritize, and route relevant conversations directly into your organization are an essential component of your customer engagement program. Look for automation, workflow, contact management, and robust analytics when selecting social engagement tools.

In summary, social customer experience management involves the entire organization and the complete management team in response to the newly defined role of the customer as a participant in your business. Some of the concepts and technologies have evolved from marketing, while others are straight out of high-scale customer care. Unlike the adoption of social media tools and techniques for campaign efforts, however, picking up on and implementing ideas generated through social customer engagement requires the participation of the entire organization.

Hands-On: Review These Resources

Review each of the following, combining the main points covered in the chapter and the ways in which the following resources expand on these points. Then tie each into your business or organization:

- Paul Greenberg’s “Social CRM Comes of Age”

- Jeremiah Owyang’s listing of social CRM tools

www.web-strategist.com/blog/2009/12/08/list-of-companies-providing-social-crm

- The Edelman Trust Barometer

Hands-On: Apply What You’ve Learned

Apply what you’ve learned in this chapter through the following exercises:

- Find examples of where your customers are behaving like the new social customer today. What are they telling you about what they want and expect?

- Find examples of bloggers or other social participants who are influential in ways related to your product or industry? Was it easy or hard to find these people?

- Review the tools and platforms you use today to manage customer information and customer interactions. How “socially aware” are they? Where are the gaps?