Chapter 1

Social Media and Customer Engagement

Social technology is now part of business: The growing role of online social interaction in people’s lives has made social a must-have for anyone making or providing a product or service. After all, if our customers are social, then business and the way it is run must be also.

The unfortunate result is a sort of land rush to build brand outposts in places like Facebook and Pinterest, too often without fully understanding the range of options that exist for social efforts and the business opportunity that social technologies—implemented in a strategic and systematic manner—actually offer. This chapter tackles the basics of what makes a social strategy work.

Chapter contents:

- The social feedback cycle

- The Social Web and engagement

- The Operations and Marketing connection

The Social Feedback Cycle

For a lot of organizations—business or non-profit—social media use begins in Marketing, Public Relations, or Communications. This makes sense, too, given the compelling events that typically drive interest in social media at a senior level, such as:

- A slew of negative comments online.

- Messages—good or bad—that have gone “viral.”

- Signs of a new generation of customers increasingly out of reach of traditional media.

- A general concern about “loss of control” of “brand voice”—what happens when the inmates really do run the asylum?

In a word, many organizations have focused on getting the right messages to customers, and they see social media in a split view: on the one hand, social media is a way to tell an existing story to an audience that has to some degree “detached” from traditional channels. On the other, it a channel where the power balance is decidedly tipped toward consumers: whether this a good or bad depends largely on factors outside of the control of Marketing.

Given this, it’s not surprising that social media projects end up being treated like traditional marketing campaigns—often seen as a relatively safe place to start the journey—rather than the efforts aimed at unlocking revolutionary experiences, like a climb up the north face—that they truly are. Too many social efforts end up pigeon-holed in short-term efforts aimed at building awareness or managing brand reputation. While laudable, the real objective of most any successful business—engagement and development of loyal customers—is missed. Is it any wonder that so many social media campaigns run their course and then fizzle out?

To be fair, there are many successful and innovative social media marketing programs. But approaching the Social Web from the perspective of “what can I tell you” predictably fails to produce the significant business outcomes that are possible given this new and ubiquitous, real-time, two-way communication medium. Missing this opportunity is unfortunate because social technology and the ability to step beyond pure marketing efforts are within the reach of nearly everyone. The technologies that now define a contemporary online-enabled marketplace—technologies commonly called social media, the Social Web, or Web 2.0—offer a viable approach to drive change deep inside business to produce better experiences for customers. There is something here for most any organization, something that extends beyond marketing and communications.

This chapter, beginning with the social feedback cycle, provides the link between the basics of social media marketing and the larger idea of social technologies applied at a whole-business level. Social technologies make it easy for people to create and publish content, to share ideas, to vote on and curate the contributions of others, and to recommend things based on their own experience. As a sort of simple, early definition, you can think of this deeper, customer-driven connection between operations and marketing as social business.

Customers have always done these things, of course. But now they do them at scale, in public. No longer satisfied with advertising and promotional information as the sole source for learning about new products and services, consumers have taken to the Social Web in an effort to share their own direct experiences with brands, products, and services to provide a more real view of their experience. At the same time, consumers are leveraging the experiences of others before they actually make a purchase themselves. All this has forced a change on the well-established norms of business marketing and management. In short, the management of these customer experiences—not just the experience at the point of sale or traditional point of service—is as a result your primary challenge.

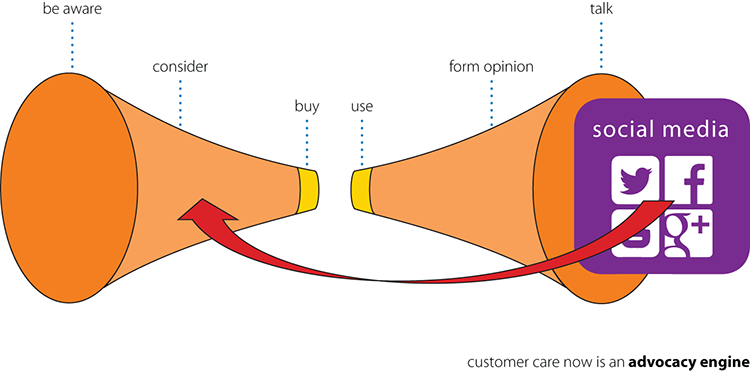

Figure 1-1 shows the classic purchase funnel, connected to the Social Web through digital word of mouth (aka social media). This loop—from expectation to trial to rating to sharing the actual experience—is now a part of almost every purchase or conversion process; people are turning to people like themselves for the information they need to make smart choices. These new sources of information are looked to by consumers for guidance alongside traditional media, combined with advertising and brand communications, which are still very much a part of the overall marketing mix. The result is a new vetting that is impacting—sometimes positively, sometimes negatively—the efforts of businesses and organizations to grow their markets.

Figure 1-1: The social feedback cycle

Open Access to Information

The social feedback cycle (hereafter referred to as the feedback cycle) is important to understand because it forms the basis of your ability to manage the social customer experience. What this feedback cycle really represents is the way in which Internet-based publishing and social technology have connected people around business or business-like activities. This new social connectivity applies three ways: between a business and its customers (B2C), between businesses (B2B), and between customers themselves (C2C, also known as peer-to-peer).

This more widespread sharing has exposed information more broadly. Information that previously was available only to a selected or privileged class of individuals is now open to all. Say you wanted information about a hotel or vacation rental property: Unless you were lucky enough to have a friend within your personal social circle with specific knowledge applicable to your planned vacation, you had to consult a travel agent and basically accept whatever it was that you were told. Otherwise, you faced a mountain of work doing research yourself rather than hoping blindly for a good experience in some place you’d never been before. Prior to visible ratings systems—think TripAdvisor, HomeAway, or AirBnB—you could ask around but that was about it, and “around” generally meant nearby friends, family, and perhaps colleagues.

The travel agent, to continue with this example, may have had only limited domain expertise as well, lacking a detailed knowledge of rental versus hotel properties in the specific location you were interested in. This knowledge, or lack of it, would be critical to properly advising you on a choice between renting a vacation property and booking a hotel. An entire travel vertical—rental vacation properties—was created by the simple ability to post rental properties online, organize the listings for easy browsing, and overcome consumer hesitation by providing actual ratings and reviews. These services now provide tens of thousands of rated and reviewed options in both popular spots and off-the-beaten-path locations within reach of a click.

An entire business around empowering consumers looking for vacation options has been created by a shift in technology. In that spirit, ask yourself: What is social technology doing—or about to do—to your business? Consumers turn to social technology in part for more information and in part for better information. Access to information has long been an issue—correctly or incorrectly—that has dogged financial services, pharmaceutical, and insurance sales to name just a few: Is the recommendation based on the needs of the customer, the incentive offered by the equities broker, the drug’s manufacturer, or the insurance underwriter, or some combination? From the consumer’s perspective, the difference is everything, and in these types of industries it can be difficult for customers to get answers needed to properly evaluate complex purchases. So, they turn to each other.

Progressive Insurance, where this book’s co-author Dave Evans worked for a number of years as a product manager, implemented a direct-to-consumer insurance product as an alternative to policies sold through agents. Progressive created this product specifically for customers who wanted to take personal control of their purchases. This made sense from Progressive’s business perspective because the degree of trust that a customer has in the sales process is critical to building a long-term trusted relationship with its insured customers. While many insurance customers have solid and long-standing relationships with their agents, it is also the case that many consumers are seeking additional information, second opinions, and outright self-empowered alternatives. Customers universally want to make smart choices, and this desire is fueled by the access and choice that easily accessible web-based information brings.

Whereas information beyond what was provided to you at or around the point of sale was relatively difficult to access only 10 years ago, it is now easy. Look no further than the auto sales process and your smartphone for an indication of just how significant the impact of scalable, connected self-publishing—ratings, blog posts, and photo and video uploads—really is. This access to information and the opinions and experiences of others, along with the outright creation of new information by consumers who are inclined to rate, review, and publish their own experiences, is driving the impact of social media deeper into the organization.

Social Customer Experience: The Logical Extension

Social customer experience follows right on the heels of the wave of interest and activity around social media and its direct application to marketing. It’s the logical extension of social technology throughout and across business, inclusive of the community and marketplace in which the business operates. It takes social concepts—sharing, rating, reviewing, connecting, and collaborating—to all parts of the business. From customer service to product design to the promotions team, social behaviors and the development of internal knowledge communities that connect people and their ideas can give rise to smoother and more efficient business processes. If this seems a lot to grapple with, add one more reality to the mix: The adoption of social technology—viewed in the context of business—quickly becomes more about change management than the technology itself. That’s a big thought.

The Contribution of the Customer

It’s important to understand the role of the customer—taken here to include anyone on the other side of a business transaction. It might be a retail consumer, a business customer, a donor for a nonprofit organization, or a voter in an election. What’s common across all of these archetypes—and what matters in the context of social business—is that each of them has access to information, in addition to whatever information you put into the marketplace, that can support or refute the messages you’ve spent time and money creating.

“But wait,” as we say in sales, “there’s more.” Beyond the marketing messages, think as well about suggestions for improvements or innovation that may originate with your customers. As a result of an actual experience or interaction with your brand, product, or service, your customers have specific information about your business processes and probably an idea or two on how your business might serve them better in the future. Tap into that and your brand advocates will self-identify.

Consider the following, all of which form the basis for a customer experience associated with a transaction, an experience this customer will quietly walk away with unless you take specific steps to collect this information:

- Ideas for product or service innovation

- Early warning of problems or opportunities

- Awareness aids (testimonials)

- Market expansions (ideas for new product applications)

- Customer service tips that flow from user to user

- Public sentiment around legislative action or lack of action

- Competitive threats or exposed weaknesses

This list, hardly exhaustive, is typical of the kinds of information that customers have and often share among themselves—and would readily share with you if you asked—provided that they trusted you, were offered the means to talk directly with you, and had reason to believe that you would act on the information they shared.

Ironically, this idea-rich information rarely makes it all the way back to the product and service policy designers where it would do some real good. Whether due to “not invented here” or “not on our roadmap” or “legal advised us not to take customer suggestions” or simply “our departments don’t collaborate that way,” the result is the same: The information that you need to innovate and compete is lost. In the marketplace, this means you are fighting with one hand tied behind your back. Collecting this information and systematically applying it is, in this view, in your best interest.

Here’s an example: Suppose a customer finds that your software product doesn’t integrate smoothly with a particular software application that this customer has also installed. How would you even know? If you have a high-cost enterprise product, you may have a field team that picks up on this. But what if your product is a small, cloud-based plug-in? Enter social: This information is something you can collect through peer support channels—aka support communities—and associated analytics. It can then be combined with the experiences of other customers, as well as your own process and domain knowledge, to improve a particular customer experience and then offered generally as a new solution. This new solution can then be shared—through the same community and collaborative technologies—with your wider customer base, raising your firm’s relative value to your customers in the process and strengthening your relationship with the customers who initially experienced the problem.

The resultant sharing of information—publishing a video or writing a review—has value beyond public social forums: It is useful inside the organization, where it forms the stepping-off point from social media marketing and social customer care into social business. From a purely marketing perspective—as used here, meaning the MarCom/advertising/PR domain—this shared consumer information can be very helpful in encouraging others to make a similar purchase. It can enlighten a marketer as to which advertising claims are accepted and which are rejected, helping that marketer tune the message. Beyond that, however, this same information can also create a bridge to dialogue with the customer—think about onsite product reviews or support forums—so that marketers, product teams, your Legal department, and sales teams—can all understand in greater detail what is helping to build loyal customers and what is not. Taken to its ultimate end, this information can drive process change that results in better products, improved margins, and the general sorts of measurable gains that are associated with primary business objectives.

Prior to actually making process changes, you’ll of course want to vet this information. Listening and information gathering—treated in depth in Chapter 6, “Social Analytics, Metrics, and Measurement”—falls under the heading of more information and so drives a need for enhanced social analytics tools to help make sense of it. It’s work, but it’s worth pursuing. Access to customer-provided information means your product or service can adapt faster. By sharing the resulting improvement and innovations while giving your customers credit, your business gains positive recognition and brand advocates, customers who as a result of your recognition feel a stronger tie to the brand.

The Importance of Identity

Although customers can prove an invaluable source of information, much of this value comes from your ability to understand who this particular customer is and therefore how to evaluate or consider this feedback. Is a specific voice within a conversation that is relevant to you coming from an evangelist, a neutral, or a detractor? Is it coming from a competitor or disgruntled ex-employee? You need to know so that you can plan your response. And while the overall trend on the Social Web is away from anonymity and toward identity, it’s not a given—at least not yet—that any specific identity has been verified. This means you need tools that help you to dig deeper.

Anonymity opens the door for comment and rating abuse, to be sure. But social media also provides for generally raising the bar when it comes to establishing actual identity. More and more, people write comments in the hope that they will be recognized so as to build personal social capital.

As people take control over their data while spreading their Web presence, they are not looking for privacy, but for recognition as individuals. This will eventually change the whole world of advertising.

—Esther Dyson, 2008

With this growing interest and importance of actual identity, in addition to marketplace knowledge, social business and the analytical tools that help you sort through the identity issues are important to making sense of what is happening around you on the Social Web. Later sections tie the topics of influencer identification back to your business objectives. For now, accept that identity isn’t always what it appears, but at the same time the majority of customer comments are left for the dual purpose of letting you know what happened—good or bad—and at the same time letting you know that it happened to someone in particular. They signed their name because they want you (as a business) to recognize them.

Social Customer Experience Is Holistic

When you combine identity, ease of publishing, and the desire to publish and to use shared information in purchase-related decision-making processes, the larger role of the feedback cycle and its connection to business emerges. Larger than the loop that connects sales with marketing—one of the areas considered as part of traditional customer relationship management (CRM)—the feedback cycle wraps the entire business.

Consider an organization like Freescale, a spin-off of Motorola. Freescale uses YouTube for a variety of sanctioned purposes, including as a place for current employees to publish videos about their jobs as engineers. The purpose is to encourage prospective employees—given the chance to see inside Freescale—to more strongly consider working for Freescale. Or, look at an organization like Coca-Cola, reducing its dependence on branded microsites in favor of consumer-driven social sites like Facebook for building connections with customers. Coke is also directly tapping customer tastes through its Coca-Cola Freestyle vending machines that let consumers mix their own Coke flavors. Music service Spotify invites customers to help them determine what artists and songs belong on the service; Verizon FIOS does the same with cable channels. In the United States, DISH, Time Warner Cable, and Comcast all use Twitter as a customer-support channel. Computer-maker Lenovo does them one better—customers actually write the help articles that you find on the Lenovo website. The direct integration of social technologies in business—beyond marketing—is growing rapidly.

These uses of social technology in business are explored in greater detail in subsequent chapters. For now, the simple question is, “What do all of these uses have in common?” The answer is that each of them has a larger footprint than marketing. Each directly involves multiple disciplines within the organization to create a customer experience that is shared and talked about favorably. These are examples not of social media marketing but of social technology applied to business practices.

Importantly, these are also examples of a reversed message flow: The participation and hence marketplace information is coming from the consumers and is heading toward the business as well as other customers. With TV, radio, and print—mainstays of advertising—it’s the other way around: strictly from the business to the customers. In each of the previous examples, it is the business that is listening to the customer. What is being learned as a result of this listening and participation is then tapped internally to change, sustain, or improve specific customer experiences.

The Connected Customer

The customer is now in a primary role as an innovator, as a co-contributor, as a source of forward-pointing information around taste and preference, and as such is potentially the basis for competitive advantage. We say potentially because recognizing that your customers have opinions or ideas, actually collecting this useful information, and using the information to build your business are three different things. Here again, social technologies step in. Where social media marketing very often stops at the listening stage, perhaps also responding selectively to directly raised issues in the process, social customer experience management goes further.

First, experience management practices are built on formal, visible, and transparent connections that externally link customers with business and internally link employees to each other and back to customers. This is a central aspect of a truly social business: The “social” in social business refers to the development of connections between people, connections that are used to facilitate business, product design, service enhancement, market understanding, and more. Second, because employees are connected and able to collaborate—social technology applies internally just as it does externally—the firm is able to respond to what its customers are saying through the social media channels in an efficient, credible manner.

Before jumping too far, a point about your fear of the unknown, the unsaid, the unidentified, or even the uninformed saying bad things about your brand, product, or service that aren’t even correct! Fear not, or at least fear less. By engaging, understanding, and participating, you can actually take big steps in bringing some comfort to your team around you that is maybe more than a bit nervous about social media. Jake McKee—partner at PwC, a colleague of ours, and the technical editor for this book—attended one of Andy Sernovitz’s way-cool social media events. The group toured an aircraft carrier while it operated in the Pacific. One of the things Jake noted was that even though the deck of an active aircraft carrier—considered among the most dangerous workplaces on Earth—was to the untrained eye loud, chaotic, and therefore scary, in reality it was surprisingly fear-free. Everyone knew their place and everyone watched out for each other (and especially for Andy’s tour group). F-18s were launching 100 feet away. Average age of the crew? 19. Fear? None.

The point is this: You can overcome fear with structure and discipline—on the deck of an active aircraft carrier or in business on the Social Web. Chapter 5, “Social Technology and Business Decisions,” Chapter 6, “Social Analytics, Metrics, and Measurement,” and Chapter 7, “Five Key Trends,” provide insights into the organizational adoption of social technology along with the best practices and essential quick-start tips to put you at ease.

The Social Web and Engagement

Adopting social technology and its supporting processes can enable the critical activities of engagement and response. This section provides a starting point for understanding how. But beware: It’s a different viewpoint than that which applies to engagement in traditional media. Engagement is redefined by consumers when acting in an open, participative social environment. This is a very different context from the read-only setting in which traditional media practitioners typically define engagement, so take the time here to understand engagement as it is used in this book.

Engagement on the Social Web means that customers or stakeholders become participants rather than viewers. It’s the difference between seeing a movie and participating in a screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The difference is participation. Engagement, in a social sense, means your customers are willing to take their time and energy and talk to you—as well as about you—in conversation and through processes that impact your business. They are willing to participate, and it is this participation that defines engagement in the context of the Social Web.

The engagement process is, therefore, fundamental to successful social marketing and to the establishment of successful social customer experience management. Engagement in a social context implies that customers have taken a personal interest in what you are bringing to the market. In an expanded sense, this applies to any stakeholder and carries the same notion: A personal interest in your business outcome has been established. Consider the purchase funnel shown in Figure 1-1. As customer conversations enter the purchase cycle in the consideration phase of the sales process, there is a larger implication: Your customer is now a part of your Marketing department. In fact, your customers and what they think and share with each other form the foundation of your business or organization.

The impact is both subtle and profound—subtle in the sense that on the surface much of social customer experience management amounts to running a business the way a business ought to be run. Businesses exist—ultimately—to serve customers through whose patronage the founders, employees, shareholders, and others derive (generally) an economic benefit and are therefore ensured a future in running that business. At times, however, it seems the customer interest gets dropped. The result can be seen on Twitter most any day by searching for the hashtag #FAIL.

The Social Web also drives profound change in the sense that the stakes in pleasing the customer are now much higher. Customers are more knowledgeable and more vocal about what they want, and they are better prepared to let others know about it in cases of over-delivery or under-delivery. On top of that, not only are customers seeing what the business and the industry are doing, but they are building their own expectations for your business based on what every other business they work with is doing. If Walmart can quickly add dynamic ratings and reviews to any product it sells, the expectation is that American Airlines will prominently place customer ratings on every flight it flies. Ask yourself: If flight attendants, by flight, were rated according to service and demeanor by past fliers and that information were used to make future flight choices in the same way as on-time performance, how would the overall flying experience change? It happens in restaurants. We all have a favorite waitperson and frequently ask for that person or book a table on the night when he or she is working. Airlines like Delta now ask in their surveys, “If you had a business, would you hire this person?” Like their competitors Southwest, Alaska Airlines, and United, they have placed emphasis on service quality; all four enjoy higher than average Net Promoter scores partly as a result.

By the way, the rating of service employees as the basis for making purchase decisions cuts both ways: What would happen if patrons were also rated? Car-share services like Uber and Lyft took a page out of eBay in the way that ratings are applied to both buyers and sellers: If you gain a reputation on Uber as a passenger for being a bit of a jerk, expect to stand on the street corner longer. Patrons now protect their reputations as a way of guaranteeing future consideration when conducting business in these markets or requesting services of these providers, ironically lowering the costs of doing business and boosting margins as a result; dealing with jerks is expensive!

The Rules of Engagement

If social media is the vehicle for success, the Social Web is the interstate system on which it rides into your organization. Social customer experience management, therefore, is about equipping your entire organization to listen, engage, understand, and respond directly, specifically, individually, and measurably through active conversation and by extension in the design of products and services in a manner that not only satisfies customers but also encourages them to share their delight with others.

Share their delight? What scares a lot of otherwise willing executives is the exact opposite: sharing dismay or worse. The fact is, negative conversations—to the extent they exist, and they do—are happening right now. Your participation doesn’t change that. What does change is that those same naysayers have company—you. You can engage, understand, correct factual errors, and apologize as you address and correct the real issues. But do watch out for what Paul Rand has labeled “determined detractors.” See the sidebar “Respond to Social Media Mentions” for a response flow chart. It’s simple, and it works.

In Chapter 8, “Customer Engagement,” and Chapter 9, “Social CRM and Social Customer Experience,” you’ll see how the basic principle of incorporating the customer directly into the marketing process extends throughout the product life cycle. In this opening chapter the focus is limited to the supporting concepts and techniques by which you can build customer participation and consideration of customer experience into your business processes. For example, encouraging participation in discussion forums or helping your customers publish and rate product or service reviews can help you build business, and it can put in place the best practices you’ll need to succeed in the future. Social business includes product design, pricing, options, customer service, warranty, and the renewal/re-subscription process and more. All told, social business is an organization-wide look at the interactions and dependencies between customers and businesses connected by information-rich and very much discoverable conversations.

So what gets talked about, and why does it matter? Simply put, anything that catches a consumer or prospective customer’s attention is fair game for conversation. It may happen among three people or three million. This includes expectations exceeded as well as expectations not met and runs the gamut from what appears to be minutiae (“My bus seems really slow today.”) to what is more obviously significant (“My laptop is literally on fire…right now!”).

How do these relate to business? The bus company, monitoring Twitter, might tweet back, “Which bus are you riding on right now?” and at the least let its rider know that it noticed the issue. Or the bus operator’s social care team may go further and ask for additional info; it may even communicate with others via Twitter and in the process discover a routing problem and improve its service generally. As for the laptop on fire, the brand manager would certainly want to know about this as soon as possible and by whatever means. That includes Twitter.

News travels fast, and nowhere does it travel faster than the Social Web. In his 2009 Wired article “Twitter-Yahoo Mashup Yields Better Breaking News Search,” writer Scott Gilbertson put it this way: “Whenever there’s breaking news, savvy web users turn to Twitter for the first hints of what might be going on.” What’s important in a business context is this: In both the bus schedule and laptop fire examples, the person offering the information is probably carrying a social-technology-capable, Internet-connected mobile device. As noted recently by Advertising Age and others, it is very likely that Twitter or a similar mobile service is also this person’s first line of communication about any particular product or service experience!

Brand managers connected to these information streams can track feedback using real-time social media analytics tools and thereby become immediate, relevant participants in customer conversations. This kind of participation is both welcome and expected to be present by customers. The great part of all of this is that by connecting, engaging, and participating, as a business manager you tap into a steady stream of useful ideas. See Chapter 12, “Social Applications,” for more on idea-generation platforms and their application in business. Take the time to understand the rules as well as the technologies that will help you build a successful social strategy.

Assessing Engagement

The Social Web revolves around conversations, social interactions, and the formation of groups that in some way advance or act on collective knowledge. The earliest analytics tools focused on listening and on understanding and managing specific attributes of the conversation: sentiment, source, and polarity, for example. Now, social technology built for engagement takes this a step further: By connecting directly with specific customers, a social care team not only can keep tabs on and respond to basic issues as they are raised on social channels, but it can also dig in and ask, “How or why did this conversation arise in the first place?” For example, is the conversation rooted in a warranty process failure? With that information the team can respond in a better manner and take measurable steps toward building brand advocates.

The adoption of social technology in business is helpful in determining how to respond to and address the detailed issues that often drive online conversations about brands, products, and services. Is a stream of stand-out comments being driven by a specific, exceptional employee? Being able to identify and measure the contributions and performance of specific social care agents will help your organization create more employees like that one. From a business perspective—and Marketing and Operations are both a part of this—understanding how conversations come to exist and how to tap the information they contain is key to understanding how to leverage your investment in social technology, to move from “So what?” to “I get it!”

Business processes based in social technologies allow organizations to capture and share insights generated by customers, suppliers, partners, or employees through social technologies in ways that actually transform a conversation into useful ideas and practical business processes. Social customer experience is built around a composite of technologies, processes, and behaviors that facilitate the spread of experiences (not just facts) and engender collaborative behavior.

An easy way to think about social technology and its application to business is in its conveyance of meaning and not just attributes such as polarity or source or sentiment, and in what a business can do in response to this information. Social customer experience is built around collaborative processes that link customers to the brand by engaging them as a part of the product development cycle. Consider the social business framework now in place at Dell.

Dell, hit hard by Jeff Jarvis’s August 2005 “Dell Hell” reference in his Buzz Machine blog posts, needed to become a brand that listened and engaged with customers, employees, and suppliers across the Web. Dell employees like Bob Pearson, now President, Austin consultancy W2O Group, and Sean McDonald, now a managing director with PwC Advisory, believe that people spend a lot of time on the Web but not necessarily on your domain buying your product. So, the engagement strategy has to begin with going out onto the Web and meeting them on their terms and on their turf. In other words, it’s better to fish where the fish are, not where you wish the fish were.

The team at Dell built on the strength it found in its customers. There were 750,000 registered users in the Dell Community at the time, with a good portion highly engaged. These customers wanted Dell to participate. Dell quickly realized that engaged users were stronger contributors and more vocal advocates of the brand. This realization was the breakthrough for the wide range of social media programs that Dell offers today. Dell’s programs are built around its customers (not just the brand), and they actively pull customers and their ideas into Dell where Dell employees collaborate and advance the product line, completing the information cycle between businesses and their customers.

Social customer experience requires the design of external engagement processes in which participants are systematically brought into the processes that power, surround, and support the business. This is achieved by implementing social technologies, but not by that alone. It also requires changes to internal roles, responsibilities, and business processes. As Joe always says, if people’s jobs haven’t changed—if someone in support isn’t doing something differently today, and also in communications, product development, web development, and so on—then you’re really not doing social at all.

The Engagement Process

What if you threw a party and nobody came? What if they came, but no one talked, ate, drank, or laughed? Engagement makes the world go round, no less in social media than anywhere else. Unlike traditional media, social technologies push toward engagement and collaboration rather than exposure and impression. Engagement is defined here to mean an intentioned interaction. But not all interactions are alike. The social engagement process moves customers in brand, product, or service-related conversations beyond consumption (reading an article) and toward active collaboration in a series of distinct steps, each built around a specific interaction type.

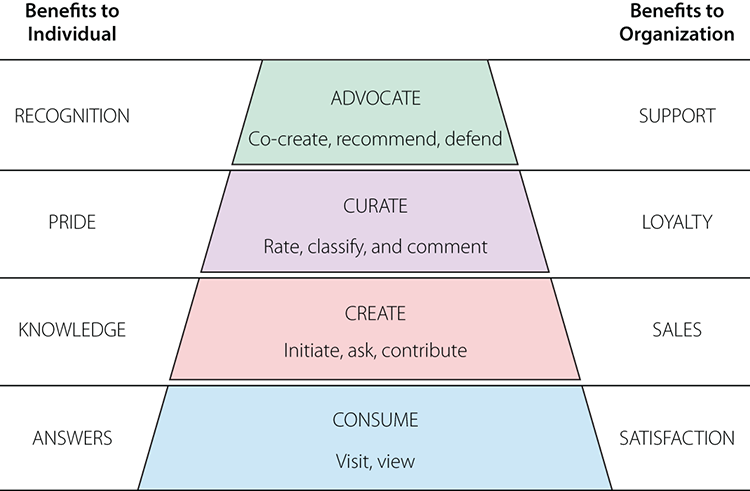

The hierarchy of engagement, shown in Figure 1-2, shows a typical progression toward increasing participation for communities associated with larger businesses. Note that creation—asking a question—often precedes curation—rating or improving the usefulness of content. In communities associated with more casual members, curation may well occur first, and can in fact be the driver of content creation.

Regardless of your actual application, you’ll see in detail how the stages of the engagement hierarchy, always starting with consumption, fit together.

Figure 1-2: Hierarchy of engagement

Consumption

The first of the foundational blocks in the process of building strong customer engagement is consumption. Consumption, as used in the context of social media, means downloading, reading, watching, or listening to digital content. Consumption is the basic starting point for nearly any online activity, and especially so for social activities. It’s essentially impossible (or at least unwise) to share, for example, without consuming first: Habitually retweeting without first reading and determining applicability to your audience will generally turn out badly. More practically, if no one knows about a particular piece of content, how can anyone share it? Further, because humans filter information, what we share is only a subset of what we consume.

As a result, consumption far outweighs any other process on the Social Web: It’s that cliché that says that the majority of people on the Web are taking (consuming) rather than putting back (creating). There’s even a rule for it, called 90-9-1 (see sidebar).

People often think that mere browsing is not a valuable activity. But if you’re creating social channels for your business, much of your value will come from browsing. Think about it: If you use social channels for support, it’s the viewing of solutions that generates value, not the creation of solutions. If you use social channels to help sell product or build your brand, it’s the viewing of social content that drives commerce clicks, not the creation of the content. The fact that the majority of users are not creating content is not the bad part of social—it’s the good part! It means that most people are using social channels to buy, use, learn, and get the most from your products and services.

Having said that, you can’t create a great social customer experience without moving your customers up the hierarchy of engagement. At a minimum, you need customer-created content to provide the trusted content that customers today want and expect. More importantly, if you don’t try, you’ll never get the rewards that come from responding to your customers desire to contribute to, and collaborate with, your business.

Creation

Creation is the act of contributing content you created. At the earliest stage, this content can be as simple as a question in a forum. A question is content, too! At more advanced stages, it can include contributing a blog article, a product review, or a video. Creation involves contributing something that others can respond to.

How do you encourage creation? Just saying “You can upload your photos!” is generally not enough. You need a good call to action. People need to know it’s OK to contribute. You need to “prime the pump” with content similar to that which you hope people will contribute. Usually you start by reaching out to customers you know and asking them to help create that starter content. Most important, however, is one key principle: You have to make it easy. Ease trumps all other values and benefits when trying to engage users.

Thinking about adding photo or video sharing to your site? Take a look at Tumblr, now owned by Yahoo. Tumblr hosts more than 160 million blogs, and there’s a good reason for that: Tumblr is absolutely simple. Will your application require a file of a specific format, sized within a given range? You can count on a significant drop in participation because of that. When someone has taken a photo on a now-common tens-of-megapixels smartphone or camera, your stating “uploads are limited to 100 Kbytes” is tantamount to saying “Sorry, we’re closed.” Instead, build an application that takes any photo and then resizes it according to your content needs and technology constraints. Hang a big “All Welcome” sign out and watch your audience create.

Getting members to participate for the first time is the tough part. Think of a topic that would be easy for everyone to comment on. In the early days of their community, UK telecommunications company BT started a thread to invite comments on a series of ads featuring an attractive couple, Adam and Jane. Most people in the UK had seen the ads, which had run for almost five years. The company asked “Where do you think this relationship will go?” Customers responded with more than 900 suggestions over 30 days, from the cheeky (“They will go back to their respective spouses”) to the far out (“Adam turns out to be an alien who crash landed thousands of years ago.”). While the community itself was focused on technical support, the thread gave newcomers the chance to participate in a fun, low-effort way. When the event was over, daily participation rates sustained that marked increase that never went away.

The business rationale for encouraging content creation is simple: People like to share what they are doing, talk (post) about the things that interest them, and generally be recognized for their own contributions within the larger community. Reputation management—a key element in encouraging social interaction—is based directly on the quantity and quality of the content created and shared by individual participants. The combination of easy content publishing, curation, and visible reputation management is the cornerstone of a strong community.

Curation

Curation is the act of rating, classifying, and commenting on content contributed by others. Curation makes content more useful to others. When someone creates a product review, the hope is that the review will become the basis for a subsequent purchase decision. However, the review itself is only as good as the person who wrote it and only as useful as it is relevant to the person reading it. Reviews become truly valuable when they can be placed into the context, interests, and values of the person reading them and when those reviews are recommended to others.

This is what curation does. By seeing not only the review but also the reviews of the reviewers or other information about the person who created the review, the prospective buyer is in a much better position to evaluate the applicability of that review given specific personal interests or needs. Hence, the review is likely to be more useful (even if this means a particular review is rejected) in a specific purchase situation. The result is a better-informed consumer and a better future review for whatever is ultimately purchased, an insight that follows from the fact that better informed consumers make better choices, increasing their own future satisfaction in the process.

Curation is an important social action that helps shape, prune, and generally increase the signal-to-noise ratio within the community. Note as well that curation happens not only with content but also among members. Consider a contributor who is rewarded for consistently excellent posts in a support forum through member-driven quality ratings. This is an essential control point for the community and one that, all other things being equal, is best left to the members themselves: curation of, for, and by the members, so to speak.

Curation is, therefore, a very important action to encourage. Typically, curation is done by people who are regular users and care about the quality and usefulness of the information. In casual communities, assigning ratings can be the small, low risk step that encourages content creation and participation. It’s a lot like learning to dance: Fear, concern of self-image, and feelings of awkwardness all act as inhibitors of what is generally considered an enjoyable form of self-expression and social interaction. Introducing your audience to curation makes it easy for them to become active members of the community and to then participate in more substantive creative and collaborative processes that drive community membership and health over the long term.

Advocacy

At the top of the ladder of the core social customer experience building blocks is advocacy. Advocacy is the act of co-creating, recommending, and defending on behalf of a product or a brand. Advocacy is about exerting influence—on other customers, to encourage them to embrace the products you love, and on the company, to help them create the best products and experiences for their customers.

Advocacy is commonly equated with positive word-of-mouth, and that’s obviously key in an online world. In defending the brand, customers can say things that brands can’t say themselves, or can’t generally say with the same credibility and trust. To achieve such a level of relationship with a customer is indeed a profound thing. Consider the Net Promoter score, or NPS: Companies that embrace the methodology believe that likelihood to recommend is in fact the most important indicator of a customer’s satisfaction. A high-valued NPS is a clear step toward realizing advocates.

But advocacy doesn’t stop at word-of-mouth. Advocates want to participate in your business. They’ll let you know when you don’t meet your usual high standards. They’ll insist not only that you fix a problem for them but fix it for everyone else as well. They see themselves as your partner. They want to work with you—to co-create, in the current parlance—to make things better.

Like other social behaviors, there is a scale against which social activity can be viewed in perspective: The collective use of ratings aside, consumption, curation, and creation can be largely individual activities. Someone watches a few videos, rates one or two, and then uploads something. Someone asks a question or posts a reply. It’s a two-way conversation, it’s social, but it’s fairly low on the collaboration value scale.

Activities like blogging are a bit more collaborative. Take a look at a typical blog that you subscribe to, and you’ll find numerous examples of posts, reinterpreted by readers through comments that flow off to new conversations between the blogger and other readers. Bloggers often adapt their “product” on the fly based on the inputs of the audience, correcting or rewriting the original post.

Wiki or knowledge base articles take the process further. Several customers contribute to the same article. A customer may collaborate with a company employee. Neither one owns the end result; the outcome is collaborative, not individual. Ideation tools do something similar: An idea contributed by an individual is refined by comments from other users and then rated by other users to reflect its importance. The outcome—a refined and prioritized set of ideas—is again a collaborative product, not an individual one.

In some ways, what we just described—encouraging basic interaction and participation—is the easy part. The hard part is taking direct input from a customer and using it in the design of your product. Take bloggers for example: Many effective bloggers take direction from readers’ comments and then use these contributions to build a new thought based on the readers’ interests and thoughts. This is actually a window into how a socially enabled business can operate successfully by directly involving customers in the design and delivery of products and services. How so? Read on.

Consider a newspaper where a journalist writes an article and the subscribers read it. The primary feedback mechanism—letters to the editor—may feature selected responses, but it’s certainly not all responses, and it’s generally the end of the line. The original journalist may never again come back to these individual responses and is even less likely to build on these comments in future stories. Traditional media is as a result very often experienced as a one-way communication.

Now move to a blog or a blog-style online paper, something like the Huffington Post or Mashable. With the online publications of these businesses, audience participation is actually part of the production process. The comments become part of the product and directly build on the overall value of the online media property. The product—news and related editorial and reader commentary—is created collaboratively. As content consumption moves to smart devices, news will increasingly find its way back to the living room where it may again be discussed socially—even if in the online living room—with the (also digital) social commentary as an increasingly important part of the content.

How does this relate to business? Taking collaboration into the internal workings of the organization is at the heart of social business. This is equally applicable to the design of physical products, long-lived (multiyear) services, and customer relationship and maintenance cycles. By connecting customers with employees—connecting parents with packaging designers for kids’ toys, for example—your business can leapfrog the competition and earn favorable social press in the process.

The Engagement Process and Social Customer Experience

Taken together, the combined acts of consumption, creation, curation, and advocacy carry participants in the conversations around your business from readers to talkers to co-creators. Two fundamentally important considerations that are directly applicable to your business or organization come out of this.

First, your customers are more inclined to engage in collaborative activities—sharing thoughts, ideas, concerns—that include you. It may be a negative process: Your customers may be including you in a conversation whose end goal is forcing a change in your business process in response to a particular (negative) experience they’ve had. Or, it may be “We love you…here’s what else we’d like to see.” The actual topics matter less than the fact that your customers are now actively sharing with you their view of the ways in which what you offer affects them and therefore what they are likely to say if asked. By considering social behaviors and inviting customers into these processes, your business or organization is in a much better position to identify and tap the evangelists that form around your brand, product, or service.

Second, because your customers or other stakeholders have moved from reading to creating and collaborating, they are significantly closer to the steps that follow collaboration as it leads to engagement: trial, purchase, and advocacy. The engagement process provides your customers with the information and experiences needed to become effective advocates and to carry your message further into their own personal networks. People talk about how companies need to change and learn in the new social era; they forget that customers are changing and learning too!

As examples of the value customers and organizational participants will bring as they share their experiences and ideas, consider the following:

- You don’t get to the really good results until you go through the necessary venting process by people you’ve previously ignored: Opening up a dialogue gives you a natural way to enable venting and healing.

- The way you deal with negative issues is an exhibition of your true character: Become a master at accepting critical feedback and turning it into improved products and services and then reap the rewards.

- It’s your job to understand what was really meant, given whatever it was that was actually said. “I hate you” isn’t always as simple as it sounds: This kind of seemingly intense negativity may arise because the customer involved likes you enough to actually feel this way when things go wrong.

- Ultimately, your customers want to see you do well: They want your product or service to please them.

Shown in Figure 1-3, there are distinct benefits to engagement and advocacy that apply well beyond the immediate customers involved. Advocates gather around your brand, product, or service to spread their experiences for the purpose of influencing others. For you, it’s a double payoff: Not only does it make more likely the creation of advocates through social technologies, but because these and other social applications exist, the advocates that emerge are actually more able to spread their stories.

Figure 1-3: Benefits of engagement

In the end, the engagement process, delivered via the thought-out application of social technology, is about connecting your customers and stakeholders with your brand, product, or service and then tapping their collective knowledge. It’s about connecting and conveying what you learn into your organization to drive innovation and beneficial change. With this linkage in place, the larger social feedback loop is available to you for use in ways that can—and do—lead to long-term competitive advantage.

The Operations and Marketing Connection

So far this chapter has covered two primary topics: the importance of understanding the mechanics of the social feedback cycle and the collaborative inflection point within the larger social engagement process. Engagement has been redefined in a social context as a more active (participative) notion compared with the decidedly more passive advertiser’s definition of engagement—reading an ad or mechanically interacting with a microsite—typically applied in traditional media, where the term engagement ad literally means “an ad you can click to see more.” That’s not what participants on the Social Web generally think of when they think of engaging.

The final section ties the mechanical processes of the social technologies together with the acts of participation and collaboration and establishes the foundational role of the entire business or organization in setting up for success on the Social Web. The social feedback cycle—the loop that connects the published experiences of current customers or other stakeholders with potential customers or other stakeholders—is powered by the organization and what it produces. This is a very different proposition from a traditional view of marketing where the message is controlled by an agency and the experience is controlled—often in relative isolation—by the product or services teams and others even more distant.

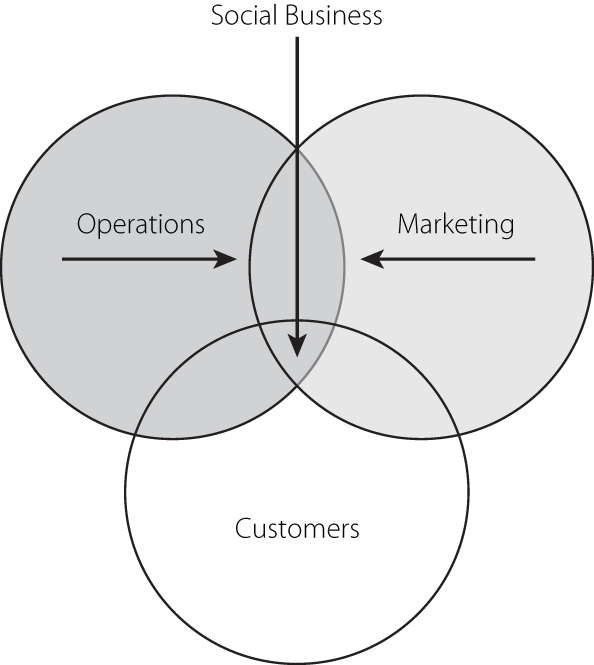

Figure 1-4 shows the alignment that needs to occur between what can loosely be called operations and the marketing team as they contribute to the effort of managing customer expectations and experiences. Included in operations are the functional areas that control product design and manufacturing, customer service and support policies, warranty services, and similar. In other words, if marketing is the discipline or function within an organization that defines and shapes the customer’s expectation, then operations is the combined functional team that shapes and delivers the actual customer experience. Looked at this way, it’s clear that operations has a major stake in the management of the social customer experience.

The connection between the disciplines of marketing and operations and social media—and in particular the conversations, ratings, photos, and more that carry as content the stories and evidence of distinct customer experiences—is this: The majority of conversations that involve a brand, product, or service are those that arise out of a difference between what was expected and what was delivered or experienced. Disappoint customers, and they’ll talk about that. Exceed their expectations, and they’ll talk about that too. Basically delivering as promised isn’t typically talk-worthy.

Figure 1-4: The marketing-operations connection

If this sounds vaguely familiar, think about the underpinnings of the Net Promoter methodology: We tend to talk more about what was not expected than what was expected. Note too that in this simple relationship between expectation and actual experience, the folly of trying to control conversations on the Social Web after the fact becomes clear: Conversations on the Social Web are the artifacts of the work product of someone else—a blogger, a customer, a voter, and so forth—who typically doesn’t report to the organization desiring to gain control! You can’t control something that isn’t yours to control.

Instead, it is by changing the product design, the service policy, or similar in order to align the experience with the expectation or to ensure the replicable delivery of delight, for example, as Zappos does when it upgrades shipping to Next Day for no other reason than to delightfully surprise a customer. At Zappos, it’s not just a story of an occasional unexpected upgrade that got blown out of proportion in the blogosphere. When bloggers—and customers—rave about Zappos, it’s for good reason: Zappos creates sufficient numbers of moments of delight that many people have experienced them and gone on to create and share content about them. It’s expensive—and Zappos isn’t always the lowest cost shoe retailer. But in the end, delight wins. Zappos set out to build a billion-dollar business in 10 years. As a team, they did it in 8. Ultimately, it is the subsequent customer experiences—built or reshaped with direct customer input—that will drive future conversations and set your business or organization on the path to success.

Connect Your Team

Social media marketing is in many ways a precursor to operating as a social business. Social customer experience is most effective when the entire business is responsible for the experiences and everyone within the organization is visibly responsible for the overall product or service. When engagement is considered from a customer’s perspective—when the measure for engagement is the number of new ideas submitted rather than the time spent reading a web page—the business operates as a holistic entity rather than a collection of insulated silos. The result is a consistent, replicable experience that can be further tuned and improved over time.

When it comes to rallying the troops to support your organization-wide effort, there is no doubt that you’ll face some pushback. Very likely, you’ll hear things like this:

- We don’t have the internal resources and time.

- We lack knowledge and expertise.

- Not till you show me the value and ROI.

- We don’t have guidelines or policies.

- It’s for young kids—not for our business.

- Our customers will start saying bad things.

One of the first tasks you are likely to face when implementing a social media marketing program and then pushing it in the direction of social business is the organizational challenge of connecting the resources that you will need. The good news is that it can be done. The not-so-good news is that it has to be done.

When you’re a marketer, one of the immediate benefits of a social media program is simultaneously gaining access to a large audience and being able to understand by listening to what people are saying as it relates to you and your business objectives. Through listening you can analyze what you find that is relevant to your work and then use this to develop a response program (active listening) coordinated or delivered through customer care. This information can be presented internally and done in a way that is inclusive and draws a team around you. Listening is a great way to start, though it will quickly become clear that this is best done through an effort that reaches across departments and draws on the strengths of the entire organization. Anything you can do to get others within your business or organization interested is a plus.

Basic listening and analysis can be done without any direct connection to your customers or visible presence with regard to your business or organization on the Social Web. In others words, it’s very low risk. While it may not be optimal, the activities around listening and analyzing can be managed within the marketing function. As you grow beyond that, however, into actively responding to individual customers (social customer care) or implementing a support forum (peer-based care), you’ll want both to invest in a platform built for measurable engagement and to enlist functions and resources across your organization. With workflow-enabled engagement platforms—for example, using a social customer care platform that automatically routes tweets about warranty issues to customer service—you can certainly make it easier to oversee all of this and therefore gain confidence in your ability to consistently provide excellent social customer care.

Building on this approach, when you move to the next step—responding to an individual customer about a policy question, #FAIL experience, or product feature request—you’ll be glad you pulled a larger team together and built some internal support. Otherwise, you’ll quickly discover how limited your capabilities inside the Marketing department to respond directly and meaningfully to customers actually are, and this will threaten your success. How so?

Suppose that you see negative reviews regarding the gas mileage of a new model car you’ve introduced, or you see posts about an exceptional customer service person. In the former case, you can always play the defensive role—“True, but the mileage our car delivers is still an improvement over….” Or, you can ignore the conversation in hopes that it will die out or at least not grow. (Note: It probably won’t just die out.) In the case of the exceptional employee, you can praise that particular person, but beyond the benefit of rewarding an individual—which is important, no doubt about it—what does it really do for your business?

Ignoring, defending, and tactically responding in a one-off manner doesn’t produce sustainable gain over the long term. What would really help you in building a successful, enduring business is delivering more miles per gallon or knowing how to scale the hiring, training, and retention of exceptional employees. You need to get control of the process issues that define customer experience—and doing that requires a larger team. This means building a team that is inclusive in membership beyond any single discipline within your organization.

Who is that larger team, and how do you build it? The answers may surprise you: Your best allies may be in unlikely or previously unconsidered places. Consider, for example, the following:

- Your legal team can help you draft social media and social computing policies for distribution within the organization. This is great starting point for team-building because you are asking your legal team to do what it does best: to keep everyone else out of trouble.

- You can connect your customer service team through social analytics tools so that they can easily track Twitter and similar conversations.

- You can champion the implementation of a social customer platform within your customer care department to more effectively respond to customers raising questions on social channels and the answers provided in response.

- Enlist your own customers. Most business managers are amazed at how much assistance customers will provide when asked to do so. Read on.

Your Customers Want to Help

While it may surprise you, your customers are part of the solution. They are often the biggest source of assistance you have. Flip back to the engagement process: consumption, curation, creation, collaboration. At the point that your customers are collaborating with each other, it is very likely that they are also more than willing to provide direct inputs for the next generation of your product or service or offer tips on what they think you can quickly implement now. Starbucks customers have been busy offering such ideas on the “My Starbucks Idea” platform. In the two years that followed its implementation in 2008, about 80,000 ideas were submitted with over 100 direct innovations as a result. While 100 out of 80,000 may not seem like a lot, consider that Starbucks’s own customers did most of the filtering, and 100 ideas implemented translates into one customer-driven innovation introduced in a retail context every week. That’s impressive, and it paid off in business results.

Ideation and support applications are discussed in Chapters 9 and 12. They are among the tools that you’ll want to look at, along with social media analytics and influencer identification tools covered in Part II of this book. However you do it, whether planning your social customer experience program as an extension of an in-place marketing program or as your first entry into social technology and its application to business, take the time to connect your customers (connection fuels engagement) to your entire team (so that collaboration between customers and employees is possible).

Review and Hands-On

This chapter provided a foundation for thinking about social customer experience, providing a framework for building a sufficient team inside your organization to successfully implement a social customer experience management effort. Chapter 1 connected the current practice of social-media-based marketing—a reality in many business and organizations now—with the fundamental application of the same technologies at a whole-organization level aimed at managing the social customer experience, thereby setting up next generation of customer engagement.

Review of the Main Points

This chapter focused on social media and social technology applied at a deeper business level for the purpose of driving higher levels of customer engagement. In particular, this chapter established the following fundamentals:

- There is a distinct social engagement process. Beginning with content consumption, it continues through creation, curation, and advocacy. These reflect increasing stages of collaboration, creating stronger links between you, your colleagues, and your customers.

- Operations and marketing teams must work together to create the experiences that drive conversations. The social feedback cycle is the real-world manifestation of the relationship that connects all of the disciplines within your organization and drives the customer experience.

- Collaboration—used to connect customers to your business—is a powerful force in effecting change and driving innovation. Collaboration is, in this sense, one of the fundamental objectives of a socially aware business strategy.

Now that you’ve gotten the basics of the engagement process and understand the usefulness of social applications along with the ways in which you can connect your audience, employees, and business, spend some time looking at the following real-world applications. As you do, think about how the engagement process is applied and about how the resultant interactions leverage the larger social networks and relevant communities frequented by those who would use these applications.

Hands-On: Review These Resources

Review each of the following, taking note of the main points covered in the chapter and the ways in which the following resources demonstrate or expand on these points:

- Search the Web for “Dell Hell” to understand what happened at Dell and how it inspired other companies to start on the social journey.

Read the Nielsen Norman Group’s report on Social Media User Experience.

Review Starbucks’s “My Starbucks Idea” ideation application:

Read the Altimeter State of Social Business Report to understand how companies are responding to the needs of their social customers.

www.altimetergroup.com/research/reports/the_state_of_social_business_2013

Look at the blog of Peter Kim, on the topic of social business:

Look at the work of Jeremiah Owyang, focused on the topic of social technology and collaboration applied to business:

Hands-On: Apply What You’ve Learned

Apply what you’ve learned in this chapter through the following exercises:

- Define the basic properties, objectives, and outcomes of social applications that connect your customers to your business and to your employees.

- Define internal processes that enable efficient resolution of customer-generated ideas.

- Map out your own customer engagement process, and compare it with the engagement process defined in this chapter.