Chapter 3

Social Customer Experience Management

Customer experience is the hottest topic in business today, and it should be. Research clearly shows that customer experiences, positive and negative, have a direct impact on the bottom line. It can be a challenge to put together all the pieces that make a customer’s experience great, and in this context social technologies represent both a threat and an opportunity: They simultaneously empower customers to share experiences as well as find alternatives with just a few clicks. This chapter explains how the notion of customer experience emerged and what it means today, in a social world.

Chapter contents:

- Understanding customer experience

- Are you ready for SCEM?

- SCEM and measurement

- The essential role of the employee

Understanding Customer Experience

At first blush, customer experience might seem just a fancy term for good, old-fashioned customer service. In fact, it’s a radically different way to think about how customers relate to companies and how satisfaction, loyalty, and other business benefits really come about.

Where did the notion of customer experience come from? Not too long ago, the dominant model for understanding customers and the decisions they make was the rational actor model. In this model, customers make rational decisions based on a kind of informal cost/benefit analysis. The products that sell best are those that customers believe to offer the maximum benefits for the lowest costs. To make rational choices, customers need information, and so in the rational actor model, the process of evaluating and selecting products is a matter of gathering and processing information. Consumer Reports, the magazine of ratings and reviews, was the de facto embodiment of the information essential to the rational customer.

In the mid 1980s, an alternate model of the customer emerged—the experiential model. In this model, many factors—emotional as well as rational—influence a customer’s choices. The experiential model was first articulated in an academic paper written by Morris B. Holbrook and Elizabeth C Hirschman. The paper’s title says it all: “The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun.” In the late 1990s, Joseph Pine and James Gilmore took a further step; in their book The Experience Economy they argued that every company, whether Walt Disney Company or Progressive Insurance, should think of itself as selling experiences, not just products or services.

Customer experience management is now a discipline, embraced by many of the world’s largest brands. Frameworks and models abound. Hearing a lot lately about the customer journey? That’s part of the movement too. In 2011, Bruce Temkin, a pioneer in the field in his time at Forrester Research, cofounded the Customer Experience Professionals Association (CXPA) for people whose role in their organization focuses on customer experience. Some of these people, bearing titles like vice president of customer experience or even chief customer officer, report directly to the CEO.

Forrester Research continues its leading work in this area: Harley Manning and Kerry Bodine detail this in their 2013 book, Outside In: The Power of Putting Customers at the Center of Your Business. Notably, they are helping to quantify company performance in customer experience in their annual surveys. In their 2011 report, they quantified the potential dollar benefit of great customer experience, by industry. For example, they found that hotels that offer superior customer experience could tap into $495 million in revenue from additional night’s stays by satisfied customers.

As the customer experience movement shows, businesses are responding to the reality that experiences drive customer behavior. And just in time, too: In the era of the Social Web, the experiential life of customers is on full display—in comments on social networks like Facebook and Google+, in questions posted on Twitter and in ratings and reviews appearing on almost every retail website.

Fortunately, the power of companies to create and respond to experiences is greater than ever before. The combined result of these transformed markets where experiences play a more significant role, together with widely available social technology, is the emerging practice of social customer experience management (SCEM).

Are You Ready for SCEM?

Creating great customer experiences is not just about new channels and new platforms. Companies that think of social as a new kind of website are bound to fail. Rather than a web makeover, getting the social customer experience right takes a new kind of company. The following sections establish the ground rules.

Social Businesses Are Participative

At the heart of your social customer experience program is a simple idea: that operating a business on the Social Web revolves around participation with and by your customers. Underlying this idea are two fundamental modes of behavior: collaboration with your customers and collaboration between individual customers.

Collaboration between customers offers organizations the invaluable crowd wisdom that is one of the unique benefits or social technologies. When businesses and organizations adopt holistic social customer experience management, including both customer-company and customer-customer collaboration, everyone wins. By bringing customers in and by directly involving stakeholders in the design and operation of the organization, constructive ideas built around fundamentally measurable processes inevitably emerge.

To serve social customers you need to see your organization as a socialbusiness. A social business is one that is prepared—with vision, culture, business processes, and technology—to participate in an ongoing dialogue with customers and to understand its place in the markets and communities that surround these conversations. Companies that can collaborate, inside and outside the organization and with the marketplace and surrounding physical community as a whole, are often better able to respond to marketplace dynamics and competitive opportunities than a traditionally organized and managed firm.

The takeaway is this: Efforts leading to the creation of a social business often begin with identifying or creating an opportunity for participation with (or between) customers, employees, or stakeholders and then pursuing those opportunities effectively.

Common Misconceptions

One of the biggest misconceptions about online customer opinion—learning about what your customers want is certainly part of building a social business—is that it consists mostly of complaints and rants. Not so. A 2013 study by Adobe found that social mentions online are actually slightly positive in the United States—an average of 5.07 on a scale of 1 (highly negative) to 10 (highly positive)—and trending upward. Results from other English-speaking countries were 5.04, 5.24, and 5.36 for Australia, Canada, and the UK, respectively. So while your efforts initially focus on the negative—helping those who are dissatisfied or needing assistance—it is important to understand that social comments overall are much more balanced than you might think. This is important when you move from resolving problems to developing advocates.

Another common misconception is that great internal collaboration is a prerequisite for collaborating successfully with customers. There’s no disputing the fact that good internal information sharing helps you present a more consistent, high-quality experience to customers across channels. Good internal collaboration also makes it easier to innovate, to implement great ideas that customers suggest or inspire. But beware: internal collaboration efforts are in many ways more complex and difficult than external, customer-facing efforts. A 2013 study by Gartner, for example, found that only 10 percent of internal social networking efforts succeed. This isn’t a reason not to undertake such efforts, but it does suggest not holding off on customer-facing efforts that can pay real dividends right now until some distant day when internal efforts are perfected.

The experience of one high-tech company we know illustrates what’s potentially lost when “perfect internal collaboration” becomes the gating factor for all other social business efforts. The company began internal and external social efforts at the same time, with (as is typical) different teams, departments, and technologies being deployed. Eighteen months later, the internal effort was finally ready for launch, having navigated the shoals of HR policy, IT standards, the goals of different department heads, and various mid-flow organizational changes. In that same timespan, the customer-facing social customer care effort, which launched in just 90 days, had already attracted 250,000 customers to join and participate. How much time would have been lost in building customer care if it had not been started until after the internal efforts were sorted out? In competitive markets, 18 months is forever!

Successful external social efforts often begin by thinking about the natural communities that exist around your brand. Consider support communities as one starting point: Different communities might exist around different product lines or different geographies. Existing customers might have different needs than prospects. In addition to customers, a company’s partners or distributors typically offer additional opportunity for external social efforts. Successful efforts begin by prioritizing your objectives and first-steps based on likelihood of success, understanding that it’s easier to move forward from success than to try again after a failure.

Speaking of moving ahead from success, you might be tempted to create a social effort aimed at customer groups you don’t currently address, for example a younger demographic then you currently serve. That’s certainly a valid and legitimate aspiration: You can use social technology to broaden your existing audience. But here’s a word of caution: It’s usually much better to start with those who already know and engage with you—we call it an addressed audience—and then branch out to new audiences once your initial efforts are successful.

Autodesk, a provider of business software, first created a community for design and engineering professionals who use its tools in the workplace. This was a natural audience that was eager for places to share knowledge and tips on how to use the software successfully. Today, with the burgeoning maker movement, Autodesk’s community is also used by a new generation of consumers and hobbyists. The company, in turn, has begun to craft products with those consumers in mind, including apps available on the Apple App Store. It’s unlikely that Autodesk would have enjoyed the same success path if they started by trying to attract the maker communities first.

Build around Customer Participation

Regardless of who the members of your community are, strong communities are built around the things that matter deeply to the members of that community: Skills, problems, passions, and causes are common engines of social efforts.

The strongest communities often are powered by more than one of these. Consider the community created by French beauty-products retailer Sephora. The Sephora BeautyTalk community (http://community.sephora.com) is powered by the passion for high-quality beauty products, the skills and knowledge required to select and use those products, and the confidence and pride that people gain by using those products appropriately. Regardless of your company or industry, you’ll find parallels in the types of discussions, the ways that members interact with each other and with the brand, and the way in which BeautyTalk links customers to each other and to Sephora.

BeautyTalk is what our friend Sean O’Driscoll at PwC calls a “help and how-to community.” You may think of how-to as limited to things like home improvement, but many products and services generate how-to questions. Communities and social networks, in turn, are great ways to connect customers so they get the how-to help they need. It’s important here to recognize that successful communities are not defined by your motive as an organization, whether business or nonprofit, but rather by the needs and desires of the participants within these communities.

Participation Is Driven by Passion

Getting the activity focused on something larger than your brand, product, or service is critical to the successful development of social behavior within the customer or stakeholder base and as well within the firm or organization itself. After all, if narrowly defined business interests take center stage, if the social interaction is built purely around business objectives, then what will the customers of that business find useful? What’s in it for them?

Further, how will the employees of that business rally around the needs of customers? At Southwest Airlines, employees are bound together in service of the customer, through a passionate belief that the freedom to fly ought to be within the grasp of anyone. So much so that when times are tough or situations demand it, the employees don the personas of Freedom Fighters and literally go to work on behalf of preserving the right to fly for their customers. As Freedom Fighters, they keep the characteristic Southwest energy up. This translates directly into the experiences that drive positive conversations about Southwest Airlines.

Being a Freedom Fighter is the kind of powerful ideal that unites businesses and customers and the kind of passion—for travel, exploration, or the ability to go out and conquer new markets as a business executive—that powers Southwest. It’s the kind of passion around which a business traveler’s community can be built.

While we focus here on networks and communities, in a more general sense customer experience management as a whole is built around your understanding of the passions and aspirations of your customers. What experiences do they want? What experiences will surprise and delight them? What will make their life easier, more productive, and more meaningful? Of these, which are most relevant to the realities and aspirations of your brand? If you can answer these questions, you can avoid the missteps that derail otherwise well-intentioned efforts. You’ll have a community that will grow by organic interest generated by and between the participants themselves, rather than by high-cost advertising or promotional efforts.

In Search of a Higher Calling

The surest way to avoid this trap is to appeal to the core interests of your members—in other words, to anchor your initiatives in something larger than your brand, product, or service. Appeal to a higher calling, one that is carefully selected to both attract the customers you want to attract and provide a natural home or connection to your brand, product, or service.

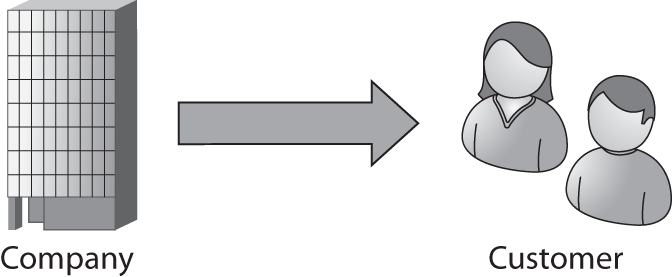

Figure 3-1 shows the traditional business model: You make it, you tell your customers about it, and they (hopefully) buy it. Figure 3-1 is largely representative of the basic approach that has defined business for the past 50 years.

Figure 3-1: Traditional business

This works well enough provided your product or service delivers as promised with little or no need for further dialogue. It helps too if it is marketed in a context where traditional media is useful and covers the majority of your market. Traditional media has wide reach, and it is made for commercial interruption. This provides a ready pathway to attentive customers and potential markets. The downside is that traditional media is also getting more and more expensive—TV advertising costs have increased over 250 percent in the past decade—and it’s harder to reach your entire audience. What took three spots to achieve in 1965 now takes in excess of 100. Another problem is that some customers, like some members of the millennial generation, can’t be reached at all by traditional media.

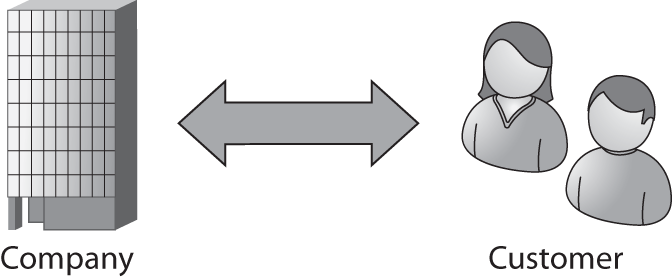

Figure 3-2 shows an evolved view of business and the beginning of a move away from a purely transactional view of the customer. The customer receives (or consumes) marketing messages, for example, and buys the product or service. But the customer’s journey doesn’t stop there. They go on to ask questions, share experiences, provide feedback, and share ideas, either directly with you or among their peers. The difference is that there is a feedback loop. Compliments and concerns can flow your way. Concerns, because they can be expressed, don’t turn into frustrated rants—provided of course that something is done about them. Recall that this opportunity to listen and understand, and thereby craft a response, is a direct benefit of participation with customers, whether through traditional methods or as now, on the Social Web.

Figure 3-2: Evolved business

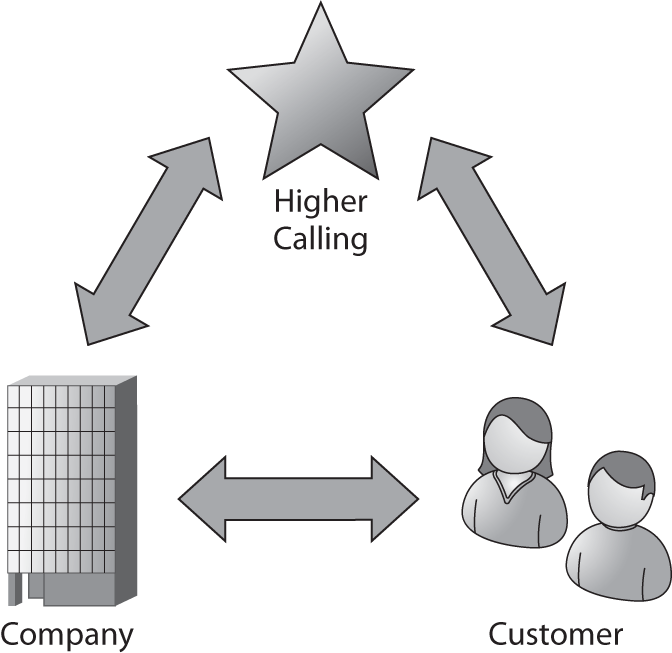

Finally, Figure 3-3 shows the business-customer relationship when the idea of a higher calling is introduced. The higher calling forms a common bonding point for both the business or organization and the customers and stakeholders, in particular in the context of social participation with a business. To be sure, savvy marketers have tapped this best practice even through their traditional campaigns: At GSD&M Idea City, where author Dave worked with clients ranging from the Air Force to Chili’s to Land Rover, Walmart, and AARP, brands were connected with customers through a shared value and purpose, something larger than the brand itself and to which both the brand and customer simultaneously aspired. This created a very powerful linkage that transcended the basic brand-consumer relationship. This same type of appeal to a common purpose or value that is larger than the brand itself can be applied in an analogous manner on the Social Web.

Figure 3-3: The higher calling

Social media takes this practice to the next level. Social media inherently revolves around passions, lifestyles, and aspirations—the higher calling that defines larger social objects to which participants relate. The social media programs that are intended to link customers to communities and shared social activities around the business, and thereby around the brand, product, or service, must themselves be anchored in this same larger ideal. Compare Figure 3-3 with Figures 3-1 and 3-2: Simple in concept, getting this larger social object identified and in place is critical to the successful realization of a social customer experience effort.

Here is an old-school example: Tupperware, and more specifically Tupperware parties. Having seen more than a few of these first-hand as a child, Dave recalls that Tupperware parties seemed to be little more than a dozen or so women getting together to spend a couple of hours laughing and talking about plastic tubs. Obviously, there was more to it: There was a higher purpose involved, a much higher purpose. Tupperware had tapped into the basic human need for socialization, and a Tupperware party provided the perfect occasion to link this need with its product line. The combination of great products and meeting its customers’ human needs (social interchange) as well as their practical needs (efficient and organized food storage, the perennially favorable economics of left-overs, etc.) has helped Tupperware build a business as timeless and durable as the products it sells.

Personal transformation is another common higher calling. In the case of Sephora’s BeautyTalk, members become more proficient at creating great looks for themselves and their friends. Similarly, in the Barclaycard Ring community presented in Chapter 2, “The Social Customer,” members become more sophisticated at managing their use of credit, avoiding credit problems, and maintaining their financial security. The McDonald “Family Arches” social business effort helps members mother in an aspirational sense, feeding their kids nutritious foods even when they’re on the go.

The list goes on. Personal transformation is an increasingly powerful trend on the Web at large: Think of the quantified-self movement—think “wearable devices that measure bodily functions”—where web-connected products like running shoes and iPhone apps help members track their achievements and share them with others in a community.

Look back at the brands and associated experiences just covered, ranging from selling products to creating experiences to creating a platform by which customers achieve their dreams. Is that powerful, or what? It is, and these are exactly the kinds of experiences you can add to your brand in support of your online presence.

$pend Your Way to a Social Presence

The appeal to a higher calling—to a lifestyle, passion, or aspiration—is what drives organic participation and growth in brand communities. The payoffs are more engagement, better engagement, and lower costs over time.

Why lower costs? Ask yourself: If you don’t have a higher calling, what powers participation? If you lack the aspiration, passion, or lifestyle connection you see in communities like Barclarycard Ring and Sephora, how do you get people to join and engage?

The answer is typically spending. You invest in advertising and promotional efforts that generate attention and buzz. This is not to overlook the great creative work that goes into promotional campaigns but rather to note that spend-driven programs versus purpose or values-aligned programs often lag in the organic growth that powers social media and long-term activity on the Web. And, they cost more!

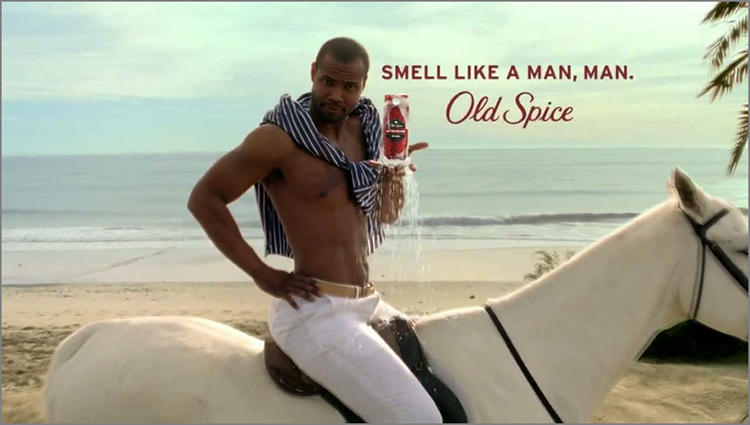

To understand why this is so, compare the social appeal of the Old Spice deodorant social media campaign shown in Figure 3-4 with the basic appeal of the brand communities we’ve discussed. The Old Spice campaign was part of television ad campaign created by ad agency Wieden+Kennedy and introduced during the 2010 Super Bowl. Following the event, the ad was viewed more than 3 million times on the Old Spice YouTube channel. To capitalize on the ad’s success, Old Spice staged a 36-hour social media event in which questions posed by fans on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube received responses in the form of videos featuring the star of the ad, Isaiah Mustafa. Old Spice posted more than 180 new videos to YouTube over the course of the event, directly in response to questions and comments from fans. The videos were viewed 5.9 million times and generated 22,500 comments from viewers.

Figure 3-4: Old Spice “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” campaign

The Old Spice social media campaign included many of the same platforms that would be used in a social customer experience effort, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. But attention and participation in efforts like this die out unless continually primed by more ads, promotions, and contests. From purely a traditional marketing and advertising standpoint, the campaign was a brilliant success. But while social, it’s a very different thing than creating an ongoing, collaborative relationship with customers that grows, organically, over time. Here again, your business objectives are critical: If you are seeking current market awareness, then spending to build your social presence makes sense. But if you are after long-term, sustained participation, then ultimately you’ll need to connect with members at a more fundamental level.

Truth is, you probably need a blend: In social customer channels participation and organic growth occur naturally. Promotion may be needed at launch, or when major additions or changes occur, but it’s not required to drive daily activity. Great social efforts grow organically based on an individual’s realization of a reason to be there: Members see the value in more members, so they actively encourage their friends to join. The obvious purpose and basic appeal of these sites combine to drive organic growth.

When charting your course in social customer experience, be sure that you distinguish between social media campaigns—like the Old Spice campaign—and social programs that more tightly link the personal aspirations, lifestyles, passions of customers with the business and its products and services, like Barclaycard, Sephora, or Autodesk. Social-media-based marketing efforts like the Old Spice campaign can drive awareness—and there is value in that. But social customer experience efforts develop long-term, ongoing relationships with customers, and there’s compelling (and measurable) value to the brand in that, too.

Build Your Social Presence

Campaign-centric communities are not the focus of an SCEM program. If you find yourself thinking “campaign,” you are heading for either social-media-based marketing or traditional/digital marketing that is made to look like social media. Beware: The focus of social customer experience—distinct from social media marketing—is on the application of the Social Web to business in ways that are driven fundamentally through organic versus paid processes and that are intended to benefit your business generally versus sell products specifically.

Organic communities and Social Web activities built around a business are designed to exist independently of marketing campaigns, with the possible exception of initial seeding. They are intended to inform the business, to connect it to its audience, to encourage collaboration between customers and employees toward the objective of improving the business, and to sustain this over time for the purpose of driving superior business results. The preference for organic growth rather than spend-driven growth is not to say that there is no value in spend-driven communities. Significant promotional value can arise out of measured fulfillment against marketing and advertising goals.

Instead, this preference arises out of the economic value of organic growth, as an alternative to paid growth. Social technology programs are centered on core business objectives and expressed through an appeal to the aspirations, lifestyles, passion, and of customers. These types of programs are specifically put in place to encourage collaborative participation. The collaboration that occurs between customers and between customers and employees is the root focus of SCEM.

Figure 3-5 shows the fundamental relationship between experiences that are talked about (word of mouth), community participation, and the function of the brand outpost. Unlike social media marketing, the application of the Social Web to the business itself views the participants as an integral component of the business, rather than simply participants in a campaign. In this context, the naturally occurring (nonpaid) activities of participants are the most valuable. The design of the social business components is powered by the activities that are sustained through participant-driven interest.

Figure 3-5: The social business

Your Business as a Social Trigger

People gather around a shared aspiration, lifestyle, or passion in pursuit of a sense of collective experience. As the early research into brand communities showed, these people are often motivated by a desire to talk about a brand, product, or service experience with each other, relating this to what they have in common. What they have in common may in part be that brand, product, or service, but it is generally also something deeper. Apple products—and the customer following they have created—are a great example of this: Apple owners are seemingly connected to each other by Apple products, and in a deeper sense they are also connected by the ethos of Apple and the smart, creative lifestyle associated with the brand.

For LEGO enthusiasts—and in particular adult LEGO enthusiasts—there is a gathering that occurs on LEGO’s owned (more technically referred to as “on-domain”) community along with a variety of other fan-created websites, forums, and blogs such as LUGNET.com. Conversations appear to revolve around LEGO products, but in reality the higher calling is the shared passion for creation, which LEGO (as a product) facilitates. While LEGO creation may bring members to the community, and while it may be the common thread that unites a seemingly disparate group, the camaraderie is what keeps members together year after year.

A business or organization is itself in many respects a social place. In much the same way, the social business is a place where employees and customers gather together around a common purpose of creating the products and services that define—and are often subsequently defined by—the brand and its higher purpose. Employees and customers, together through collaboration, create the experiences they want. Together they are responsible for the business. When the conversations that result are a reflection of this shared interest of both customers and employees, the conversations themselves are very likely to be powerful expressions that carry the business or organization forward.

This kind of end result—an expressed passion around a brand, product, or service—is associated with the higher stages of engagement. Beyond consumption of content, the activities leading to advocacy are engagement in the form of curation, creation of content, and collaboration between participants.

Brand Outposts

Communities like those referenced from LEGO and Sephora are an important part of these companies’ SCEM strategies. Because they are part of the brands’ own websites—on-domain—the brand has the ability to craft the experience exactly as they want, to manage it effectively, and to measure the results very precisely.

As a result of the growth in social activities on the Web there is a natural expectation on the part of consumers to find the brands they love in the social sites they frequent. As a matter of course, customers expect this kind of presence and participation off-domain as well. So in addition to the branded community efforts just described, an alternative (or complementary) approach to connecting a brand or organization with an existing community also exists: the creation of a brand presence—known as a brand outpost—within an established social network or online community such as a Facebook business page, a Twitter account, or a YouTube channel, to list just a few.

In creating a brand outpost—in comparison to an on-domain community—there need not be any reason other than the expectation for the brand to be present and a tie back to business objectives that are served by such a presence. There does, of course, need to be a relevant contribution by the brand, product, or service to the network or community it wishes to join. Simply posting TV commercials to YouTube is in most cases not going to produce engagement beyond the firm’s own employees and perhaps their families watching these commercials. New content created for YouTube—for example, the videos that Freescale encourages its employees to post—is the kind of content that is both welcomed and appreciated, since it is created specifically for this venue and with a social objective in mind.

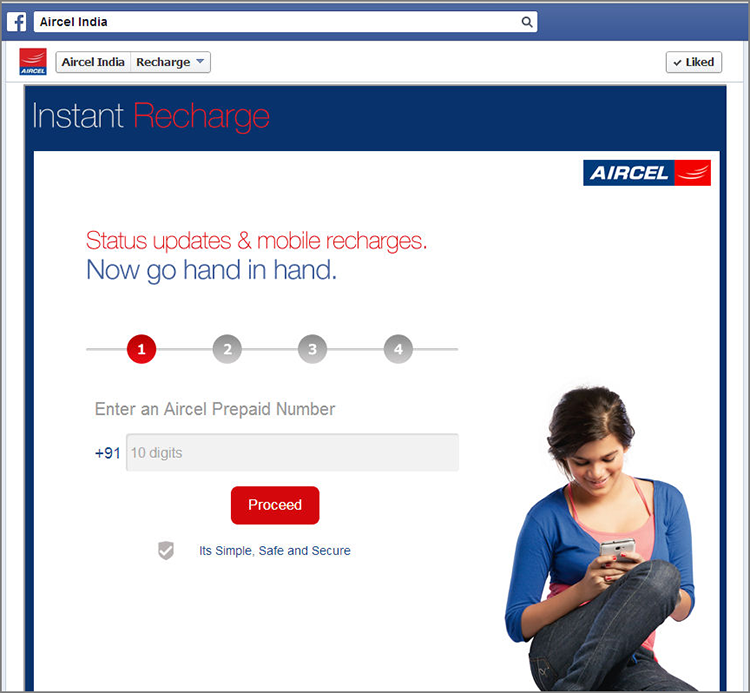

Members expect to find their favorite brands on their favorite social networks. Sometimes this means bringing functionality from the website out to the social network. For example, Aircel, an Indian telecom provider, created a Facebook application that gives Aircel customers the ability to recharge—in this case, meaning to add minutes to their prepaid plans. The Aircel recharge application is shown in Figure 3-6.

Figure 3-6: Aircel: Facebook recharge

More often, however, companies are bringing live engagement rather than just functionality. Citing its own business objectives around improving customer service and customer satisfaction, Australia’s Telstra uses its Twitter presence (@telstra) to answer customer questions. Telstra did this partly out of recognition that Twitter is a burgeoning customer service channel and partly because—as is the case with Facebook and other leading social networks—its own customers expect it to be there. The Twitter account is part of Telstra’s crowd support efforts, which also include on-domain elements such as product reviews, support forums, and an idea exchange.

Presence in existing social networks is welcomed because it makes sense from the perspective of consumers. Most brands are present in all of the other places where people spend time: on TV, on the radio, in movies (before the show and integrated into it), in all forms of outdoor advertising, and at sports events and more. Social sites—the new gathering place—are no exception. Movie studios, soft drink brands, auto manufacturers, and more are all building brand outposts on Facebook and other social sites because their audience spends significant time on those sites. Many of the brands and organizations participating in the Social Web are coincidentally skipping the development of dedicated product microsites and even major TV brand campaigns in favor of a stronger presence in these social sites.

As a part of your overall social business strategy, don’t overlook the obvious: Facebook, Google+, Twitter, LinkedIn, Pinterest, and SlideShare. All offer places where your business or organization can add value to the larger social communities that naturally form around these social sites.

SCEM and Measurement

Concerns about the measurability of social efforts and the benefits thereof are somewhat paradoxical. In fact, the migration to the Web has made business far more measureable than ever before, and social is no different. Chapter 6 explores measurement and metrics in depth. As an initial step into the integration of metrics within your SCEM programs, however—and to get you thinking about this aspect of undertaking a social business effort—consider measuring conversion and participation.

Conversion

Conversion is a concept often left to ecommerce specialists, but it’s relevant to every social business and Social Web effort. Think of the kinds of conversion you need to achieve to make your social efforts successful:

- Target audience to visitors

- Visitors to return visitors

- Visitors to contributors

- Participants to repeat contributors

Conversion doesn’t end there. You may want to convert contributors to different types of contributions: from forum answers to product ideas, from text comments to video, from contributing content to curating. Further, there are probably conversion events outside your social channels that you want to encourage as well: conversion to a purchase, membership in a loyalty program, subscription to marketing email lists, and so forth. Adopting the language of conversion can help you convey progress and value to your stakeholders. Your boss may not know why a page view matters, but every businessperson understands conversion.

Participation

Participation is one of the easiest things to capture and track. Comments, replies, new topics, reviews, ratings, and so forth—every contribution represents active participation. Individually, they indicate what each user values and wants to do. Collectively, they can be used to assess the overall levels of interest and activity within the community or network.

There are also measures of what is sometimes called passive participation. A visit to the community that does not involve a contribution is still a useful metric. Similarly, metrics like unique visitors, page views, video views, or topic views can help you understand what is of greatest interest to your members. Given that most members at any given time are participating passively, one could argue that passive metrics are in fact the most important starting point for understanding the value your social efforts are creating.

Reputation systems are designed to incent participation, but they are also a great way to measure participation. Participants in on-domain communities, for example, are often rewarded through increasing social rank based on contribution to the community. Upon joining, you may be assigned the rank of visitor and then over time earn your way to expert status as you contribute content and earn positive ratings from other members. Behind the scenes, the platform is calculating your rank based on a formula defined by the community manager. Related metrics include the following:

- Number of members who have achieved top ranks

- Percentage of members who have achieved top ranks

- Percentage of content contributed by top-ranked users

- Percentage of top-ranked users who have participated in the past 30 days (retention)

If the reputation system includes badges, medals, points, or other rewards, you might measure and report them similarly to the way you measure and report rankings.

In addition to reputation, there is an equally important related concept: distribution. Companies active on the Social Web need to understand not only who is influential or has ranked up in the eyes of fellow community members but also how these members and others in the community are distributed. Here’s an example: Suppose a certain thread in your support forum collects 100 contributions. It’s important to understand the makeup in the origin of these comments; did you get 10 posts each from 10 people or 100 posts from a single user?

Community participation, like participation in social groups offline, is typically not equally distributed. As noted in Chapter 1, “Social Media and Customer Engagement,” the general principle known as 90-9-1 is often invoked to convey the idea of participation inequality in communities: At any given time, 90 percent are merely browsing, 9 percent are participating casually, and 1 percent are participating frequently. The 1 percent are often referred to as “superusers” or “superfans.”

Community managers and the organizations they work for often conclude that a more equal distribution would be better: Wouldn’t it be better to have most people participating modestly than to have some people participating a lot and most people not participating at all? But do you even know how participation in your community is divided? And more important, how does this relate to your underlying business objectives and the objectives of your customers? In reality, the numbers rarely break down exactly in this proportion, but to be sure participation is almost always unequal. Keep this in mind as it’s something you should measure.

Like other social measures, there are more advanced and technically grounded approaches to understanding who is participating and how participation is distributed: Lithium Chief Scientist Michael Wu has used a statistical concept called the Gini coefficient to quantify participation inequality. Analyzing communities in the Lithium database of enterprise communities—the largest such database in the world—Dr. Wu has uncovered some interesting insights, among them that communities consisting of business customers are much less unequal than communities of consumers.

If you’d like to use the Gini coefficient for yourself, social media strategist Bud Caddell has outlined a very straightforward way of doing so. While his method assumes the presence of a point system, you can just as easily use a simple metric such as posts or comments for doing the calculation yourself. Using this method, you can measure very precisely the progress you are making in creating a community that is less unequal—and therefore more representative—over time.

Business Value

Except for sales conversions, none of the metrics we’ve discussed are direct measures of business value. Some may therefore suggest these metrics be disregarded, that they are soft or squishy metrics. Measure return on investment, they say, not posts or registrations!

“Measure ROI” is a certainly a great rallying cry, but that said, it also misses an important point: Just as there is a role for ROI, there is a role for indicators of conditions that lead to ROI. “Measure (only) ROI” is comparable to telling a manufacturer “Don’t measure output from your assembly line! Measure sales!” Most manufacturers know better: After all, if the assembly line stops, you can’t have sales because you have nothing to sell.

Similarly, companies with successful SCEM programs have found that customers who engage in the brand’s social channels will buy more, buy more often, and remain customers longer than customers who don’t. They know that getting customers to engage is a process that creates better relationships, more satisfaction, and more sales over time. They measure their ROI, yes. But they also measure the engagement that makes ROI possible.

Other Measures

In addition to the measures of what is happening within the community or brand outpost, where the activities are occurring also lends itself to measurement.

Relationships themselves are worth tracking. To what extent is a community driving the creation of relationships? How many are being formed and between which community members? This can be understood by tracking the number of unidirectional (think following on Twitter) relationships as well the number of mutually affirmed friendships or other similar connections that exist. Add to this the relative number of communications that flow between mutually connected users to create a measure of the importance of relationships in day-to-day activities.

Outposts and communities—the places where brand-enabled social activity happens—are a source of quantitative data that leads to an assessment of value. Within these social spaces, tracking the number of member versus nonmember interactions (if the latter are permitted), the number of times members log in, and membership abandonment (for example, members who have not logged in for 90 days or more) all provide a basis to understand—quantitatively—what is happening inside social communities and by extension with the organizations that implement social-media-based business programs.

Chapter 6 provides an in-depth treatment of these and additional metrics. As you work through the next sections, keep these initial measurement techniques and sources of data in mind. Rest assured that when you’re implementing social computing and social media techniques as a part of a business strategy, the outcomes can most certainly be held to quantitative performance standards.

The Essential Role of the Employee

Ultimately, getting SCEM right depends on more than understanding what your customers or stakeholders are talking about and how that relates to your firm. It depends as well on connecting your employees into the social processes. For example, the insights collected from social channels may be routed to and applied in marketing, to operations areas like customer support, or to other departments within the organization where it can be acted on.

The final link in the chain—and remember the conversation about ordering internal versus external efforts at the opening of this chapter—is therefore to connect employees (organizational participants in the more general sense) to each other and into the flow of customer information. This completes the customer collaboration cycle, shown in Figure 3-7, and enables the business to capitalize on the implementation and use of social technologies.

Figure 3-7: The customer collaboration cycle

Empower an Organization

Consider the following scenario: Imagine that your employer is a major hospital chain. Clearly, this is a complex business and one that customers readily talk about. Health care in a sense is one of the “this was made for social” business verticals: It cries out for the application of social technology.

Taking off on social media marketing, imagine that you are in the marketing group—perhaps you are a CMO, a VP of marketing, or a director of communications or PR or advertising for a community hospital. You’re reading through social media listening reports, and you find conversations from a new mother that reflects a genuine appreciation for the care and attention she received during the birth of her child. You also find some pictures uploaded by the people who attended the opening of your newest community health care center. Along with that you find other conversations, some expressing dissatisfaction with high costs, unexplained charges, a feeling of disempowerment—in short, all of those things outside of the actual delivery of quality health care that make patients and their families nuts.

In health care, or any other business vertical for that matter, what you’re discovering is the routine mix of conversations that typify social media. So you get interested, and you begin monitoring Twitter in real time, using a free tool like TweetDeck. One day you notice that a patient and her husband have checked in: They seem to like your hospital, as you note in the tweets you see in real time via TweetDeck as they enter your hospital. By the way, this is an entirely reasonable scenario (and in fact actually happens). When Dave flies on United, he routinely posts to @United on Twitter—as often to ask a question as to simply say thanks for a great experience—and very often hears back soon after. People do exactly the same thing when they enter a hospital and many other business establishments. Remember that if a mobile phone works on the premises, so do Twitter, Facebook, and Foursquare.

A few more tweets from your newly arrived patient and spouse pop through as they head from your hospital check-in to the waiting area and finally to pre-op. And then you see the following actual tweet, posted from inside your hospital, shown in Figure 3-8.

Figure 3-8: An actual hospital tweet: What would you do?

Looking at Figure 3-8, if you saw this tweet, in real time, what would you do? By clicking into the profile data on Twitter and then searching your current admittance records, you could probably locate the person who sent it inside your hospital in minutes. Would you do that, or would you let the opportunity to make a difference in someone’s life, right now, just slip away?

It’s these kinds of postings that take social business to a new level. Beyond outbound or social presence marketing, social business demands that you think through the process changes required within your organization to respond to the actual tweet shown in Figure 3-8. It’s an incredible opportunity that is literally calling out to you. Don’t let it slip away, which in the case above is what happened. That is not only an opportunity lost but a negative story of its own that now circulates on the Social Web.

The conversations that form and circulate on the Social Web matter to your business, obviously through the external circulation they enjoy and the impact they have on customers and potential customers as a result. But they also have a potential impact inside your organization: Each of these conversations potentially carries an idea that you may consider for application within your organization, to an existing business process, a training program, or the development of delight-oriented key performance indicators (KPIs). You are discovering the things that drive your customers in significant numbers to the Social Web, where they engage others in conversations around the experiences they have with your brand, product, or service. As such, these would be considered talk worthy, and if you were to tap the ideas directly and incorporate them into your business, you’d be onto something. You are exploring the conversations that indicate a path to improvement and to competitive advantage, but only if you can see the way to get there.

Too often, though, instead of taking notes, marketers sit there frozen in panic. As a marketer, what are you going to do in response to posts like that of Figure 3-8? Your hospital Facebook page, your New Parents discussion forum, and your connection to the community through Twitter are of basically no help in this situation. Marketing outreach through social channels is designed to connect customers to your business and to give you a voice alongside theirs, a point of participation, in the conversations on the Social Web. All great benefits, they are certainly the core of a social media marketing program. Problem is, you’ve already done this. Yet the challenging conversations—and opportunities lost—continue.

Distinctly separate from social media marketing, the challenge facing marketers in health care and near any other consumer-facing business, B2B firm, or nonprofit is not one of understanding or being part of the conversations—something already covered through your adoption of social media analytics to follow conversations as they occur. Rather, the challenge is taking action based on what customers are saying and then bringing a solution to them to close the loop. The challenge here is getting to the root cause of the conversation and rallying the entire organization around addressing it. That’s why the panic sets in, and that’s what makes social business so hard.

It’s at this point that social media marketing stops and social customer experience begins. Going back to the health care example, billing systems, in-room care standards, and access to personal health care records all require policy changes, not a marketing program. Hospital marketers are certainly part of the solution, but only a part. Social customer experience extends across the entire organization and typically requires the involvement of the C-suite or equivalent senior management team. Connecting employees, tapping knowledge across departments, and conceiving and implementing holistic solutions to systemic challenges is difficult. What is needed is a methodology that can be consistently applied. Touchpoint analysis—discussed in more detail in Chapter 5 is extremely useful in this regard. Touchpoint analysis helps pinpoint the root causes of customer satisfaction as well as dissatisfaction. Social customer experience takes off from this.

In short, connecting employees in ways that encourage knowledge sharing converts whole teams from “I can’t do this in my department” paralysis into “As a collaborative business, we can solve this.” It allows employees to more fully leverage learning, by being aware of what is going on all around them in the business and in the marketplace. Customers are often more than willing to share their ideas, needs, and suggestions and even to put forth effort. The problem is, as the “Knowledge Assimilation” sidebar shows, most organizations aren’t set up to hear it. Some are actually built—or so it seems—to outright suppress it.

If the degree to which businesses fail to assimilate knowledge is even close to what Socialtext CEO Ross Mayfield has noted in his blog—that only about 1 percent of all customer conversations result in new organizational knowledge while 90 percent of the conversations never even reach the business—the actual loss through missed opportunities to innovate and address customer issues is huge. Turned around, if only a small gain in knowledge sharing and assimilation were made—if every tenth rather than every hundredth customer (the current assessment of typical practices) who offered up an idea was actually heard and understood and welcomed into the organization as a contributing member—the change in workplace and marketplace dynamics would be profound. In a practical sense, you’d have uncovered a source of real competitive advantage. As noted in a previous chapter, Starbucks has been implementing, on average, two customer-driven innovations per week since 2008. Take a look at its stock price over that period and ask yourself if these are perhaps related.

This is exactly what is happening with the ideation tools used by an increasing number of businesses and nonprofit organizations. Tapping customers directly, and visibly involving them in the collaborative process of improving and evolving products and services, is taking hold. Chapter 12 treats ideation and its use in business in detail.

Employees in Customer Communities

It’s funny to recall that in the dawn of enterprise communities, the conventional wisdom was that employees should not participate. In fact, businesses were taught that their customers didn’t want to see them show up. The community belongs to the customer, they were told; stay out. Companies even created customer online communities under completely new brand names, thus beginning their voyage into the new world of social by casting their most valuable asset—their brand—overboard!

Fortunately, businesses learned over time that the customer not only wanted them to show up—they expected it. And so they tentatively began to join in the conversation. In how-to communities employees provided advice that no one else could supply—after all, they made the products! In marketing channels, employees supplied the latest news on new products and services, guided by social media policies appropriately created and delivered within the organization by the legal and finance groups, working with HR. Slowly, companies began to find their role—and a role for their employees—in the new social world.

Then, Twitter arrived. Early adopters like Comcast showed that responding to customers online could generate real customer delight and earn the brand enormous goodwill. Hundreds of companies followed. Social support became not just customers helping customers in communities but company agents helping customers on off-domain social channels. Suddenly, companies are participating everywhere. If this were a movie, it would be called Return of the Company!

Amid the flood of new participation—most of it needed, much of it very good—has come a new awareness that employee participation online needs to be well managed.

Clear Policies

Most companies today have a social media policy. This policy provides guidance to employees on what they may say online in their role as company employees. The purpose of the document is two-fold: to protect the brand from damage that may result from inappropriate or unauthorized activities undertaken by employees online and to protect employees by making them aware of the risks of online blunders.

Social media policies generally do not address the challenges faced by employees whose jobs involve regular participation online on behalf of the company. When the decision is made to participate, many questions arise:

- Where should we participate? On our home base (on domain) only? On social outposts like Facebook and Twitter, and if so, on which ones? Or on passport sites as well? And which regions of the world? Most companies are selective, understanding that each channel or region can represent a significant commitment.

- When should we participate? During business hours or 24/7? Immediately or after peers have had the chance to chime in? On all topics or just on topics only we can answer? Participation sets expectations; you need to make sure you can maintain any presence you establish.

- Who should participate? Can our customer support agents simply add social participation to their duties? If so, will they need additional training? What about our product experts? What about employees who have the knowledge and are eager to help, even on their own time? Most companies require training for any employee who wants to participate under the company’s brand online.

Rules like these help companies create an experience online that customers can depend on, every time.

Specific Business Objectives

The final step in connecting employees to your SCEM program is ensuring clarity around business objectives. Understand what you hope to accomplish by participating and how you will measure whether participation has been successful.

Social efforts sometimes suffer from the “everyone else is doing it, and so I should do it too” syndrome. Advice to better define business objectives is often brushed off in the rush to deploy in Internet time. Inevitably, however, the day arrives when the investment must be justified, usually by measuring the return. A hunt ensues for ways to measure impact—any impact.

The objectives of participating online should be well defined ahead of time. Joe, whose past life in management research included a significant study of leadership development practices at companies including Levi Strauss and Royal Dutch Shell, likes to say that while great leadership can be difficult to define, there’s one thing leadership is not. Leadership is not a boss who comes to his subordinates in a panic and says, “Quick! We have to justify why we’re doing this!” Before undertaking any new effort, ensure that it is grounded in your stated, agreed-to business objectives.

Review and Hands-On

This chapter covered the concepts of social customer experience management (SCEM) and some of the demands it places on an organization. This chapter sets a foundation for the processes, cases, and specific solutions covered in detail in upcoming chapters in Part III, “Social Customer Experience Building Blocks.” For now, focus on how your customers and employees use social media today, and ask yourself, “Where are our best opportunities for connecting customers in networks and communities? What will it take on the company’s part to make this happen?” Digging into these questions will lead right into the remaining chapters.

Review of the Main Points

This chapter provided an overview of the considerations when moving toward SCEM. In particular, this chapter covered the following:

- SCEM is a natural extension of the customer experience movement, recognizing that social technologies have fundamentally changed the way customers experience brands and products.

- SCEM requires that companies view customer relationships as two-way, collaborative conversations that are broader than just the brand or its products.

- Social media marketing and the activities associated with social business are fundamentally measurable. Because the activities are expressed digitally, integrating social media analytics with internal business metrics produces useful, valuable insights that can guide product and service development efforts.

- Your employees have a major role to play in the success of your SCEM efforts, by embracing collaboration both with customers and among themselves.

With the basics of social business defined, you’re ready to begin thinking through what this might look like in your own organization and how connecting your own working team with customers through collaborative technologies can speed and refine your business processes that support innovation, product and service delivery, and similar talk-worthy programs.

Hands-On: Review These Resources

Review each of the following, taking note of the main points covered in the chapter and the ways in which the following activities demonstrate these points:

- The Temkin Group website, including the Customer Experience Matters blog

- Michael Wu’s books, The Science of Social and The Science of Social 2

- Chris Brogan’s A Simple Presence Framework, which we adapted for this book

- Consortium for Service Innovation website, how the practice of customer service is changing

Hands-On: Apply What You’ve Learned

Apply what you’ve learned in this chapter through the following exercises:

- Arrange a meeting with senior executives in your organization to talk about their views on collaborating with customers.

- Create an inventory of your current social media programs. List home bases, outposts, and passports (see the “Three Levels of Social Activities” sidebar earlier in this chapter for definitions of each) and then define the metrics and success measures for each.

- Meet with the leadership of your customer service and product design teams, and meet with legal and HR to review the requirements or concerns about connecting employees more collaboratively or engaging more fully on the Social Web.