Chapter 7

Five Key Trends

This chapter covers five key trends that are driving the adoption of social technology in business, trends that as a result are forcing organizations to change and adapt. This chapter takes a look at significant consumer technology trends, ranging from engaging right here, right now, to making a game of everything, and places each into the context of a business that is setting itself up for success in the face of seemingly constant change.

Chapter contents

- Real-time engagement

- Mobile computing

- Co-creation

- Crowdsourcing

- Gamification

Real-Time Engagement

Right here, right now. What’s going on, and what do your customers need? More importantly, if you know the answers to these questions, what can you do about it?

Listening is often the starting point for the adoption of social technology. Listening is the basis for tangible, measurable connections between your business and your marketplace. It’s also a direct link to your customers. Beyond knowing who said what, listening helps you develop a baseline so that you can more quickly spot irregularities. If a sudden new interest or accidental or unpaid celebrity endorsement kicks off a wave of excitement, or a negative event or rumor around your product or service is suddenly running through the market, you’ll see it in time to take relevant action. Combined with a response strategy and a current understanding of marketplace conversations, you can build on the positive conversations and effectively address those that are negative.

Careful listening—in the context of the Social Web, meaning listening, analyzing, and thereby understanding both the subject and the source—enables you to make sense of conversations and join into them. Rohit Bhargava, principal with Influential Marketing Group, refers to this process as active listening. In simple terms, active listening is built around paying attention to conversations and then responding based on a combination of strategy and measurement.

Active listening is a key to understanding what to do and why on the Social Web, because doing so says to your customers, employees (for internal social technology implementations), or other stakeholders (the larger collection of members, staff, or persons served, as with nonprofits or municipal organizations, for example) that you are truly interested in their ideas and what they have to say about your brand, product, or service.

By establishing listening as a core practice and using what is learned to shape your response, you invite your customers into the processes that lead to higher-value interactions and ultimately to co-creation and collaboration. Given the opportunity and the tools, your customers will readily work together to create a better understanding among themselves with regard to what you offer. The Social Web provides the infrastructure for these conversations: Off-domain social applications and social networks enable content sharing and similar participative actions that occur in and around online marketplaces. On-domain applications, support forums, ratings, reviews, recommendations, and content showing your product or service in use help inform others’ decisions, in a context that you can directly manage.

Create a Baseline

The first step in creating a baseline is active listening, using the information that is being shared for your own intelligence. Given the relative newness of the Social Web, there is a lack of guiding metrics that answer basic questions such as how much conversation should one expect or how many negative posts is too many negatives? Some would say one negative is too many, but that’s probably not realistic. In any marketplace for any product or service, there will always be a range of opinions. Think about this: If you are reading a set of reviews and everything you see is positive, do you believe it? It is, therefore, essential to establish your own baseline—recognizing the value of both positive and negative conversations—and build your response strategy off of that.

Beyond the practical problem of developing an accepted baseline, the common or best practices that might provide guidance when starting out are likewise just emerging. But even more, as your brand or organization moves toward a social customer experience orientation, the unique differentiators that apply to a specific product or service, for example, begin to dominate in importance across conversations. Rather than the generic metrics—like number of units sold—social customer experience management is about understanding the specific ways your customers are talking about, using, and imagining your products, again making it mandatory that you dig in and discover the metrics that govern your business.

As an example, you may find little or no mention of your brand on the Social Web. In this case, your objective may be to build a conversation, and your baseline is the background measure against which you can assess success. Or, there may be substantial conversation, with some relative distribution between positive, neutral, and negative. Tools like the Net Promoter® score factor in here: A score near zero indicates a roughly equal balance between promoters and detractors, something you should be able to validate (through measurement) on the Social Web. In this case, your baseline is the relatively equal distribution of promoters and detractors, and your response strategy may be directed toward increasing the measured share of promoters and/or openly addressing the issues contributing to negative conversations.

Whatever your specific starting point, it needs to combine active listening and influencer identification with a marketplace performance assessment such as the Net Promoter® score so that you can both tell what’s happening now and be able to assess performance against business objectives as you progress. That is, you need to begin with some data—what customers are saying, what they are concerned with, and so forth. Later, through collaboration you’ll convert that to the knowledge you need to truly engage with your customers. At the outset, however, what matters is extracting enough data to sort out exactly where you are right now. Here’s the good news: Most of the commercial (meaning paid) listening services provide historical information ranging from a few months of history to two years. You can use these tools to construct conversational baselines immediately.

Conversational baselines are obviously handy when you want to act now (as if that’s ever not the case!). Historical data provides the context for many of the programs that you’ll implement going forward. Using a basic listening platform—whether a service like Google Alerts, a DIY (do it yourself) toolset like SDL|Alterian SM2 or Radian6, or a full-service offering from your agency—you can establish a conversational baseline. Figure 7-1 shows such a baseline. In the example, the listening program was started January 1, and a social media effort to encourage conversation was started shortly after. The listening platform provides historical data against which any change in conversational levels can be measured. The practice of creating your own baselines and understanding their significance—along with any changes that happen over time—is essential in making sense of the conversations that you are interested in.

Figure 7-1: Baseline for conversation

As an important side note, establishing a listening baseline can help you spot and manage a crisis before it’s too late. Whether it’s a rumor about your brand or an actual (negative) event that takes place with your product or within your industry, trying to sort out who is talking and how the conversation is connected to your organization after it has become widespread is too late. Instead of fighting the fire, you’ll be swamped trying to figure out where it’s coming from, losing valuable time at a point in the crisis-management process when minutes may count. With an effective baseline program in place and an understanding of who your influencers are, as soon as you detect a rise in comments or the presence of a new and potentially damaging thread, you can be ready with a response that is directed to those who can help you.

In addition to establishing a solid baseline, create a strong internal policy that governs your organization and its application of social computing. Include notification rules, disclosure, topics that are off-limits (trade secrets, for example), and expectations for conduct. This will give significant comfort to your legal and HR groups, and it will make your social-media-based marketing and business programs more likely to succeed. Refer to Chapter 3, “Social Customer Experience Management,” and Chapter 4, “The Social Customer Experience Ecosystem,” for more on the use of social computing policies and in particular for pointers to IBM and other great starting points when developing your own social computing policies.

The New Role for Marketing

Managing (or leading) change while getting your organization ready to adopt social technologies is very often among the most challenging aspects of implementing an effective social media strategy. Realizing that effectively adopting social technology is larger than marketing presents a new opportunity. The savvy CMO or marketing director can take a much wider view of the customer processes that contribute to brand health.

The initial entry point for social media in business is often marketing—probably because the initial social applications are promotional or advertising related or focused on the Social Web and its impact to the brand. As a result, much of the initial social media seems most related to marketing and sales, and in the context of the purchase funnel it’s certainly noticed there! However, the application of social media in business carries far beyond marketing. This is evident in the expanded view of the purchase funnel and the role of the conversations following purchase as they impact the marketing function—think sales or membership or donor campaigns here—within your organization. It’s what happens after the sale, so to speak, that makes clear how far beyond marketing social media and social technologies can be applied.

Moving the application of social media beyond marketing requires that you anchor your programs in your business strategy. Social technology and technology applications must be aligned with the overall business objectives and strategic efforts, picking up on the dynamics of the purchase funnel and feedback cycle and then applying what is learned across the entire organization, beyond the purely promotional activities of product marketing.

The power of a metric like the Net Promoter Score is that it puts everyone in the business on the same page of customer accountability. The question to the customer is, “Would you recommend us?” The customer’s response is based on all of the moving parts that resulted in a particular experience, upon which the likelihood of a recommendation is predicated. When an entire organization is looking at a holistic satisfaction metric, questions get asked that wouldn’t otherwise be asked. Innovations arise that would not otherwise arise. The business actually runs—from the ground up—in ways that delight the customer.

While Dave was product manager at Progressive, one of the operation metrics that made it easy to understand the health of a particular product line was a universal metric called the combined operating ratio (COR), a basic measure of financial performance that everyone understood. It predated the Net Promoter Score and was a fundamentally different measure to be sure. While the COR was a business operations performance metric instead of a customer experience metric, sharing the COR across the entire organization focused everyone on their specific impact to the proper operation of Progressive’s business. The result was an organization that worked like a single, cohesive team and thus advanced to the upper tier of its industry.

In summary, you can use listening to build the real-time social connections between your organization and your marketplace by first understanding what is being said and how it impacts you. You can leverage basic listening to shape your organization so that when the time comes it is able to respond effectively and efficiently. You can further leverage this basic data to encourage interest and involvement across the internal processes that span work teams or functional groups, again building the cross-functional discipline that you will ultimately need to be effective in your use of social technology.

Mobile Computing

Mobile computing will force every consumer-facing company to establish a direct linkage with its customers.

Michael Saylor, cofounder and CEO, MicroStrategy, and author of The Mobile Wave

The future is social, and it is inextricably linked to mobile. Mobile means “right here, right now,” and social means “with the people around me, the people like me.” This changes everything.

Embracing change, and preparing your organization for the impact of that change, is part of successfully implementing social technology. Inside your firm, this preparation includes instilling a culture of learning so that new collaborative tools such as wikis, Salesforce’s Chatter, and Microsoft’s Yammer or enterprise platforms like SocialText are embraced rather than pushed off. Outside your firm it means recognizing the power of social technology and mobile computing, both of which are inextricably linked. Along with a culture of openness (so that employees are comfortable suggesting what may seem like wacky ideas to others in the organization) these measures can drive positive change, recognizing that dynamic is the new static.

Real Time, Meet Real Space

Perhaps more than any recent technology advance, with the exception of the Internet itself, the rise of mobile computing and its relationship to social technology is changing the world. Mobile computing, given ubiquitous network connectivity, means that anyone with the means has at their immediate disposal the ability to connect, evaluate, act, and influence others. And, driven by the relentless increase in technological capability coupled with a continuous decrease in cost, “with the means” more and more translates into an ever-wider reach of mobile social computing. Health care, education, commerce, and entertainment are all being reshaped.

If that’s the macro, what’s the micro? What’s the part of this that affects you, in your business? To start, your customers expect you to be present in the critical moments in their lives when what you do intersects with what they are doing. And they expect your involvement to make sense in their current location. Real time, meet real space. Imagine that you own a restaurant, and a business traveler lands in your city for a conference: That person expects to be able to book a table at your restaurant, if one is available, from the cab on the way in to the city from the airport. Why? Because that same customer, after checking in or updating personal status, has found three friends also in town with whom to share a meal. Or maybe you run a hospital: Imagine a new patient, sitting in the waiting room at your hospital. Your patient expects to be able to talk about what’s happening with friends or remote caregivers in order to feel more comfortable and will probably reach for a smartphone and the Social Web to do it. The list of mobile use cases goes on, each driven by the combination of peer dialog (for example, with other customers) and expert dialog (for example, with your social agents or other subject-matter experts) in the context of the present situation and location.

That intersection of content and location, of participants and settings, means your business needs to reach beyond your physical bounds: Cloud-based SaaS (software as a service) applications that provide data visualization (facts relevant to the current context) and enable choices (the applicable set of responses given those facts and the local context) through smartphone apps provide exactly this. Smartphone apps are an expression of the power of the individual in shaping the deployment and use of personal technology. As they proliferate, expect significant changes in the way you go to market, win business, and build brand advocates.

Flip back to Chapter 1, “Social Media and Customer Engagement,” and see the sidebar reference for the USAF/Altimeter response matrix—listen first in order to understand what is being said. Build an understanding of how your brand, product, or service is viewed on the Social Web—and based on that, create your roadmap for engagement. Be prepared to use social technology for outreach, marketing, hiring, and especially to respond in the event of a crisis.

As an example of the latter, suppose that an isolated issue, enabled by mobile technology, results in a fast-growing negative conversation. In January 2010, India’s Café Coffee Day, a higher-end chain coffee outlet, caught the full force of just such an attack when a group of bloggers meeting in a Café Coffee Day were asked to pay a cover charge (presumably for sitting and talking in a coffee shop) in addition to the drinks and snacks they had already purchased. Understanding the role of mobile and the fact that this event played out in a highly localized context that then spilled onto the Web, makes obvious the need to grasp and plan for the impact of mobile at every brand touchpoint.

In the case of Café Coffee Day, consider the business’s point of view: Restaurants and cafes need to balance the needs of sitting customers—enjoying conversation after a nice meal—with the needs of those waiting for an open table. In this case, there were open seats and the group was spending money, so predictably the request for a cover charge resulted in a localized uproar (the event occurred within a single store) that quickly moved onto the Social Web. The brand team’s preexisting participation and in-place crisis plans specific to the Social Web and social media saved it.

Café Coffee Day’s social team typically fielded, at the time, about 10 posts per day from customers on Twitter. Suddenly, a large spike followed by numerous posts in the following 24-hour period as more people jumped in—in technical terms, piled on—to the conversation. The brand team actually handled the event pretty well. Because they were already listening (again, credit to them for participation in social channels in the first place), they were able to spot this and respond quickly. They took action publicly (reviewing, for example, the motivation of the store owner in requesting a cover charge when no such corporate policy existed). The online team issued an apology, made amends, and wrapped it up.

But the piling on continued, and that’s what brought the brand advocates, who were also seeing what was happening, out in support of the brand. The advocates saw the event, saw what to them appeared an appropriate response from Café Coffee Day, and then took action as others seeking to cash in on the notoriety of the thread kept reposting, after the fact. The advocates defended the brand. You can see the positive (up) and negative (down) comments in Figure 7-2, and you can see that the positive comments rose as fast as the negatives. The primary event was over in a few hours, and the online storm died out not long after.

Figure 7-2: We’re listening: Café Coffee Day

Two things in the Café Coffee Day event are important to recognize. First, the brand was present in the social channels and so they quickly recognized what was happening. Second, they knew how to respond: listen, acknowledge, correct, and move on. The result was the emergence of a supportive crowd as the brand advocates moved in and a fairly balanced conversation resulted—for every hater there was roughly one lover. Had the brand team not been involved, the event would have simply gone out of control, unanswered, because without the brand’s public recognition of the actual wrong and the apology from the brand team to the bloggers involved directly, the defenders would have had no ground on which to stand.

Co-creation

Collaborative activities sit at the top of the engagement processes. As such, moving your customers, members, and employees toward collaboration is a definite must-do in your list of both marketing and (larger) business goals. Collaboration, whether internally across functional work teams or externally (involving customers in product and service design, for example), is the inflection point on the path to becoming a social business.

Collaboration in the context of your business begins by connecting the off-domain conversations of customers—sharing photos taken with the newest model camera phone your company has launched or talking about one of your new shows on a network like GetGlue—with your on-domain application. On-domain includes your forums, idea exchanges, and the network itself in the case of the relaunched MySpace. By bringing these off-domain conversations onto your network and into your forums or your mobile applications, you move your online customers into a place where you can directly engage and encourage collaborative behavior.

Encourage Collaboration Everywhere

As a basic framework for an organization-wide path toward collaboration (meaning driving high levels of engagement, as defined in the social context), consider the following set of steps developed at Ant’s Eye View, now part of PwC:

Define your objectives.

Begin with a clear view of your business objectives and an understanding of your primary customer base or applicable segment of it.

Listen.

Implement a listening program to understand the specific conversations around your brand, product, or service. Use this same program to validate the actions you are considering and then use it to measure or otherwise understand the impact of those actions.

Organize.

Organize internally and externally around what you learn through listening. Create cross-functional teams, for example, that respond fully to the customer need rather than just the functional issues you discover.

Engage.

Engage the customer through participation. Respond in the channels in which your customers are talking, implement the collaborative solutions that result, and then give your customers credit because this will encourage them to participate more.

Measure.

Aggressively measure everything until you have adequate baselines to assess the impact of the programs you embark on. You can always discontinue the collection of unneeded or uninformative data later. You can’t, however, make decisions based on information you don’t have.

Taking these steps together, collaboration occurs—or at the least is facilitated—in the fourth step; engagement is a direct result of the preceding three steps. Collaboration, in this context, requires the active participation of both the customers and the employees—of the marketplace and the organization itself.

It’s About Me…and It’s About Us

Referring back to the process leading to collaboration—content consumption, creation, curation, and then collaboration—compare content consumption as applied to traditional marketing and business processes with its social counterpart. Consumption—whether of your mass market communication or the video assets you’ve placed on your website—is often described in a traditional media sense in terms of engagement. Look more closely, though, and what’s happening in most forms of traditional media is actually a relatively passive and in most cases solo activity. Call this traditional consumption for lack of a better term. Whatever the term, this type of engagement is a relatively low-involvement form.

Now move to the social sense of engagement: What does it really mean for customers to be engaged in ways that engender conversation or sharing or the creation of new content? As people become more connected, their desire to be part of something larger increases. When someone posts “I am standing in line at Starbucks” or “Waking up to a beautiful day in Austin” on Twitter, the motivation is not sharing the fact that some particular activity is happening right now. Instead, it’s all about telling yourself that you are part of a larger community and telling that community that you appreciate its being around you. Ultimately, you are asking that community to appreciate you back, so to speak. It’s what humans do.

This is the kind of expressed ownership or belonging that manifests itself in the relatively higher levels of socially inspired engagement—and in collaboration between community members, for example. If you see Twitter (and social media in general) as a big, meaningless, narcissism-fest, think about that last point again: Participants truly value their communities and the tangible expressions of belonging. When one belongs to something, one takes personal ownership for it. This shows up in member-to-member curation, in solutions posted in help forums, in the entries developed over time in Wikipedia, and through many other similar expressions on the Social Web. This sense of participation and belonging is more encompassing than it may seem: It’s not just my own needs expressed through my own activities. It’s about us.

To be sure, to an extent social participation is “all about me,” but this includes knowing who’s (also) in line at Starbucks. Whether connected through SMS, Twitter, Foursquare, or whatever, it’s about your knowing what is happening around you and in particular with and among the people you are connected to through your entire (meaning across networks) social graph. It’s about a larger, social view of what’s around and your specific role within it as a participant.

In a resounding setback, Facebook was called out when it botched its privacy changes in mid-2010 and similarly faced pushback following its acquisition of Instagram. That said, the fact is that people willingly and knowingly share a lot more personal information than ever before, precisely so that they can see some sort of reflection in the world around them that they exist. The consequences and pushback for mass marketing are huge as the coincident drive toward alignment with brands that recognize individuals accelerates. Again, this observation:

As people take control over their data while spreading their Web presence, they are not looking for privacy, but for recognition as individuals. This will eventually change the whole world of advertising.

Esther Dyson, 2008

Across multiple forms of media—social media being no exception—consumption of content is typically the most likely activity. However, beware! Whether you’re reading the paper, watching TV, or listening to the radio or a podcast, consumption is by all counts a passive activity. Even when the activity involves social media (reading blogs, for example), 80 to 90 percent of the audience limits its activity to consumption. This is the heart of the 90/9/1 rule we discussed in Chapter 1: 90% watch, 9% participate casually, and 1% participate frequently. Your mileage may vary, but the underlying behavior is well established.

While this can be helpful from a marketing (awareness) perspective, it doesn’t directly connect customers around the brand, product, or service in the kind of social context that leads to the higher forms of engagement.

It’s important to get beyond content consumption and bring your audience to the level of a genuine connection. This means participating with them, getting them into the game, and placing yourself in it with them. The easiest way is to do this through social activities—not unlike real life—and to do it in the online social spots where your audience is already present.

As a starting activity, consider curation. Curation is built around activities such as rating, reviewing, and otherwise passing judgment on the content (or conduct!) of others in the community. Because this content has been made available in a social setting, curation is a natural next step. What does curation look like? It can be as simple as rating a post as useful (or not!).

Curation matters for two reasons. First, it is a reflection of the sensibilities and value system of the audience and/or community members. Curation and the general act of evaluating and rating content—videos, posts, articles, and so forth—make it easy for others to quickly find what’s valuable and learn about what the community values. Curation drives positive community experiences for the benefit of community members. Curation in the community and membership context helps provide a better experience for members and thereby encourages the collaborative activities seen in the higher forms of engagement. Recall that these higher forms of engagement are what one is after through the adoption of social technologies. In consumer products, for example, these higher forms of engagement lead to better products and to better understandings among customers as to why these are in fact better products.

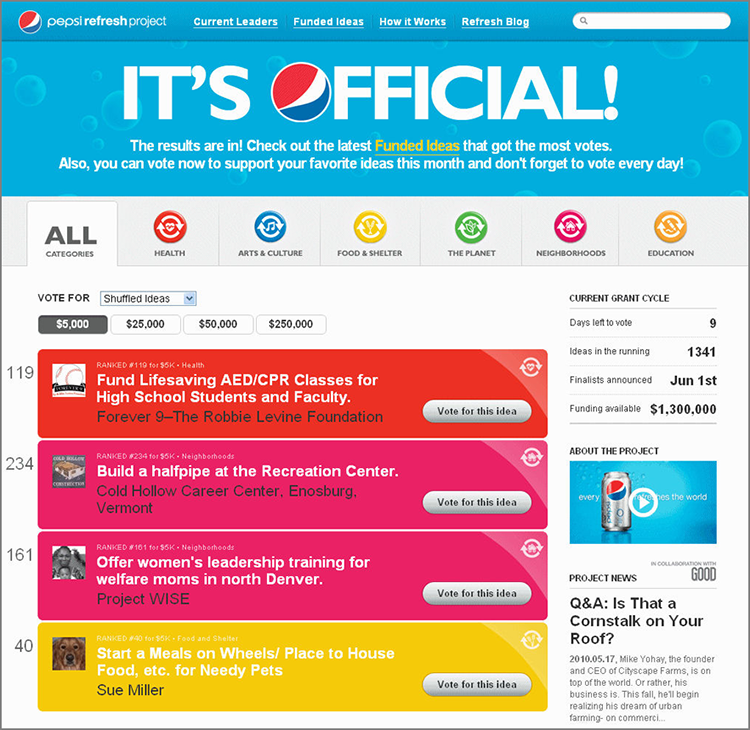

Pepsi, looking to expand its highly integrated program in the direction of increasingly social connection points, launched its Refresh project, built on cash donations from Pepsi directed to social projects that Pepsi consumers suggested and voted on. This program directly defines the Pepsi brand according to the lifestyles, passions, and causes of its customers. Pepsi’s Refresh project, shown in Figure 7-3, is an example of participant-controlled marketing by a brand built around participation and collaboration.

Figure 7-3: The Pepsi Refresh project

Social programs that go beyond awareness (consumption) and instead push for collaboration between the businesses and their marketplace stakeholders are becoming more common. They are part of an overall, holistic marketing program. Programs like Pepsi’s Refresh and Starbucks’s My Starbucks Ideas, though different in their approaches to and use of social technology, both connect the brands into the specific interests of the company’s customers. Curation, along with basic content creation, occurs naturally in these efforts, making them ideal for participative marketing efforts and the use of social technology.

Building on consumption, curation, and content creation, collaboration is the main objective when creating advocates, evangelists, and brand ambassadors. Getting people in your audience to work together collaboratively is very powerful. Working together to produce a common outcome, participants around your brand, product, or service bond with each other; and as they do, they develop a strong loyalty for the communities in which they are able to collaborate.

Find Your Influencers

Moving deeper into collaboration and its connection to listening, who is participating in the conversation is often as important as what is actually being said. Being able to identify participants who are more broadly connected or who have a specific connection in your marketplace is clearly important. In PR, for example, you connect with media influencers and similar professionals by researching or subscribing to a database of known journalists, writers, analysts, media influencers, and so on. These people sit at the entry points of the media channels that convey your message to large, defined audiences. In this setting, getting your information to specific people is as easy (or as hard) as the readiness of your own contacts database enables. Getting them to use that information the way you want them to is, of course, much more difficult.

By comparison, one of the aspects of the Social Web that makes it more challenging than traditional channels of communication is that the influencers—in the conversational leadership and direction or tone-setting sense—can be literally anyone. How do you find them? Sure, there are A-list bloggers who actively cover larger industrial and social/lifestyle verticals, just as there known media pundits and subject-matter experts who blog, write columns, host news shows, or produce similar commentary. While you may not be able to influence them directly, at least you can spot them and build appropriate relationships with them.

But what about the smaller-scale or niche bloggers whose 1,000 or 10,000 or 50,000 subscribers also comprise a meaningful slice of your customer base? Influencer identification—as a part of your overall listening program—is all about spotting and building functional, productive relationships with these individuals. This means taking an additional look into your influencers to pick out specific behaviors—what is a particular blogger focused on within the larger industry covered, and what are the larger industry or cause-related issues that most or all of the bloggers you are following are themselves focused on? Understanding the interests and hot buttons of groups or specific types of bloggers that matter to you is as important as picking out specific bloggers. These people too are influenced by their peers and operate with the benefit of their own collective knowledge. That means you need to understand this as well. The tools used to develop marketplace and specific influencer profiles—recall Buzzstream from Chapter 2, “The Social Customer”—include crawlers that navigate the Social Web looking for connections between people, so they can be used to spot both individual and group behaviors.

In a socially connected setting, the influencers in a decision process are very often the actual users of the product or service who have also established a meaningful presence for themselves online. This is exactly who you want to be engaging with as you set out on a strategic path toward collaboration and co-creation, the subject of the next section. This person might be a homemaker who blogs about health, nutrition, or family vacation planning or a photographer who publishes reviews of cameras along with techniques for lighting and subject composition. These are otherwise ordinary people, with a specific passion or interest, who have also made it a habit to publish and share what they love, hate, find useful, or otherwise want others like themselves to know about. These are precisely the people you want to find and build relationships with.

With the combination of listening and influencer identification programs in place, you can take a big step toward designing your business based on what your customers want. It’s important to understand that this goes beyond “designing the products they ask for.” Sometimes customers don’t know what they want, or they don’t know what is possible, or they want the wrong things. Don’t confuse listening and influencer identification with the wholesale turning over of your business design to your customers. At least as regards your brand, product, or service, it’s still your ship, but your customers are the crew, and so they can make or break the voyage.

Bring Social Learning (and Technology) on Domain

Using your listening program to discover and track important memes (thoughts and trends) and to spot influencers and create valuable relationships is step 1. Connecting these to your business by bringing these conversations on domain—to your support forums or your idea and innovation applications—is step 2.

The process of understanding and managing the social customer experience is highly focused on the combination of getting marketplace information where it needs to go and ensuring that you have the kind of organization that can benefit from it. Internally, this means connecting your teams with social applications like SocialText, Lotus Connections, SharePoint, or Jive. Externally, it means building powerful customer communities on platforms that support social customer experience management like those from Lithium Technologies and Salesforce.com. Dell’s Employee Storm and Philips’s use of Socialcast are examples of social technology applied internally to create powerful connections to customers. HP, Time Warner Cable, Comcast, BSkyB, and Sephora are all examples of businesses that have connected external off-domain customer interactions with on-domain collaborative and community resources. These connections were built to implement effective responses to conversations wherever they occur and to ensure that, within the organization, a specific customer’s question is directed to the right person, so the right response happens at the right time. This kind of efficient, timely response is critical to collaborative behavior.

Connect Collaboration to Your Business

With a collaborative context defined, the challenge is to connect the engagement process as defined in the social context to your business or organization’s objectives. Starbucks and Dell, using a range of social technologies, accomplished this early on and remain great case studies precisely because of the history since. They have used consumption, curation, and creation through their ideas platforms as a way to invite collaboration and then used what they learned to improve their products and product experiences. Searching the Web will produce plenty of analysis and commentary on these cases. Check them out to see how their implementation of what amounts to a suggestion box—done right—has changed their businesses.

Collaboration extends into tactical marketing programs as well: Pepsi’s Refresh is one way of involving customers directly in building a relevant brand, clearly a long-term strategic social-media-based proposition. By comparison, in early 2010 announcements from other big consumer brands like Unilever and Coke indicated that they too would be de-emphasizing branded microsites and similar media programs as components of online marketing. Instead, they increased investments in building a presence in globally significant social networks like Facebook. Coke, for example, has literally millions of fans collected around its Facebook business page.

In 2007, building on the Salesforce.com Ideas platform, Dell launched IdeaStorm. Like the My Starbucks Idea program, IdeaStorm is a transparent adaptation of the classic suggestion box, humorously depicted in Figure 7-4. What makes this updated suggestion box work is the fact that voting—done by customers and potential customers—is out in the open. The better ideas move up as they are discussed. Ideas faring less well sometimes get combined in the process, strengthening their chance of making it into the idea pool from which Dell’s product managers ultimately pull ideas.

Figure 7-4: What’s wrong with this picture? Everything!

The suggestions implemented through the IdeaStorm platform were significant, including Dell offering the Linux Ubuntu operating system as a preinstalled option. Additional ideas receiving higher than average attention include aspects of customer service, suggestions regarding the website (a primary source of income for Dell), and suggestions that preinstalled promotional software be optional. Looking at these ideas, it’s clear that social technologies have applicability and impact that extend beyond marketing.

Beyond consumer businesses, business-to-business brands—like Element 14, American Express, HSBC, and Indium—are using purpose-built communities, business-oriented networks like LinkedIn, and blogging to get closer to their own customers. In all of these efforts, the rationale is simple: Respect your audience by getting involved in the activities that they are themselves involved in. Become part of their community by bringing your brand to them. Combined with a longer-term strategic plan, these types of real-world, tactical efforts, built around platforms that already exist, are a great way to get started.

Crowdsourcing

Stepping up from co-creation, crowdsourcing tips in favor of your customers having an outright hand in design and the advancement of specific solutions or in similar roles. Crowdsourcing is an important source for innovation: As you saw with Dell’s IdeaStorm, the task of trying to make sense of 10,000 ideas randomly submitted is considerably easier if you let your customers sort the submissions for you. They’ll vote for what they want and pass on the rest. You can focus on what they want. How much faster can problems be solved when everyone involved—including your customers and your employees—work together to solve them? Collectively solving problems is a great way to show your customers you love them.

Crowdspring: Crowdsourcing

If you’ve never tried a true crowdsourcing application, here’s your chance. For a couple of hundred dollars, you can get a snappy new logo and card design for your upcoming birthday party—or just about any other event that you wanted branded. Of course, if your business needs a visual makeover, you can use Crowdspring to do that too.

Crowdspring attracts artists—designers, typographers, CSS wizards, and more—who compete for projects. Unlike eLance, where project awards are made before the actual deliverable is prepared, Crowdspring participants see the actual designs as they are evolving—in public and in view of competing designers—as the process occurs. You pay after the fact.

What really makes Crowdspring work, however, is the participation of the buyer in collaboration with the designers. Take a logo design as an example: Imagine that you want a logo for your new business. First, you create an account and define what you want—color preferences, style choices, and maybe some examples of logos you like. At this point the designers review the project, and those wishing to compete jump in and start offering design ideas.

Now, if the buyer doesn’t participate beyond this point, the designers will offer a range of styles and the buyer may pick one, but this isn’t the optimal path. One of the Crowdspring rules is that buyers have to pick a winner based on what is offered: This means it’s in the direct interest of the buyer to improve what’s offered. The best way to do this is to participate alongside the designers, not as a designer but rather through feedback on the designs being produced. As the buyer actively signals which of the submitted designs is favored, the existing pool of designers will all start shifting in that direction, and new designers, seeing the activity, will jump in, increasing both the pool and the range of choices. After 10 days, buyers choose the design they like, and the logo (or whatever design work you requested) is delivered. It’s really quite amazing how well Crowdspring works.

Here’s a great insight on crowdsourcing: The more you participate, the more the crowd will participate. Disclosure: Dave has used Crowdspring multiple times, and each time has seen the number of participating designers go up, directly in response to his participation. If you want people to participate—in any social application—show them you are serious by participating yourself.

Threadless.com: Crowd-Sourced Design

What happens when you build your business around a crowd-sourced process? For starters, your customers get involved in your products and services right from the start, which in turn can give you a continuous source of innovative suggestions on how to evolve. In addition, directly involved customers can become your most ardent supporters—or most vocal detractors.

Threadless.com—shown in Figure 7-5—offers T-shirts for sale. That sounds simple enough, but Threadless does it one better. Rather than selling their designs (or worse, designs that people could buy elsewhere), Threadless sells only the designs that its own customers create.

Figure 7-5: Crowd-sourced design: Threadless

The Threadless model works like this: People submit T-shirt designs, which are then reviewed and put to public vote. The winning designs are produced and sold, and the creators of the selected designs receive a cash reward as well as additional cash on future reprints. Threadless customers—through collaboration with each other and with the business itself—have a direct hand in shaping the product.

Threadless is a great example of a collaborative business. Founded in 2000, Threadless is also a testament to the viability of a collaborative business. According to the Small Business Administration, on average new businesses have slightly less than a 50/50 chance of making it five years, let alone twice that.

HARO: Knowledge Exchange

HARO—an acronym for Help a Reporter Out—is a knowledge exchange that was created by Peter Shankman. The basic proposition of HARO is that for every person who has a question, somewhere there is a person with an answer. The trick is to put them together, and this is what HARO does.

The context for HARO is news reporting. Reporters are often in the predicament of having to report on something they themselves don’t fully understand. This is not a knock on reporters; it is simply the reality of a technically complex world. Even if a reporter is the science journalist for a magazine or paper, it’s unrealistic to think that this person would simultaneously fully understand a nuclear power reactor, the inner workings of a rocket motor, and the various competing ideas and technical underpinnings for what to do about global warming. Yet, in the course of a week, that reporter may be asked to cover all three.

This is the classic expertise-sharing problem that led Dr. Vannevar Bush to conceive of the memex, the theorized mechanical device that provided the fundamental insight in creating the World Wide Web. Peter Shankman has applied this same thought to the job of the reporter and the challenges they face in getting accurate information about a variety of topics, even within a chosen focus area.

On one side of HARO are reporters. Reporters need information. Typically, information costs money, except online where everything is assumed to be free (not)! So here’s the dilemma: How do you get reporters the information they need without paying for it, at least directly in cash, since that would introduce a whole host of issues with regard to reporting?

The insight was this: Experts seek recognition, and being cited as an expert in a publication can be very valuable as a way to advance the career of an engineer, doctor, sociologist, prosumer (a sort of professional-grade hobbyist), and a lot of other people. HARO puts these two needs together through a searchable exchange. Reporters go looking for experts, and the experts—who have signed up and completed detailed profiles about their expertise—are thereby available for interviews by those reporters. Rather than paying in cash, people get paid in social capital and they see their own contributions gain public notice.

Gamification

In recent years few buzzwords have been as hot as gamification; predictably, the concept is widely misused and misunderstood. Gamification is the adaptation of the principles of online games to social applications, in this context to add interest to programs supporting social customer experience. When properly used, the point of gamification is not simply to entertain—nor is it to trick your customers into doing things they don’t want to do. In fact, it’s close to the opposite: It’s about enabling them to tap into what they love, what’s fun—and to thereby encourage them to do for your business what anyone playing a game would do for themselves. Read on to learn more.

Social Technologies and Gaming

Social technologies and online gaming have long been intertwined. Some of the earliest and most vibrant communities on the commercial Web were built by and for gamers. As an example, brothers Lyle and Dennis Fong, champion online gamers, created Gamers.com in 1998 as a place where fanatical fans of games like Quake and Doom could get together and share their passion and knowledge of these games. As it happened, some early users of Gamers.com happened to be employees of Dell and SONY, who individually approached the brothers with the idea of adapting the Gamers platform to the goals of an enterprise business. In Dell’s case it was customer support, while SONY wanted to bring together enthusiastic users of its gaming console.

The Fongs—seeing the clear business benefit of gaming behavior applied to business—decided to create a stand-alone company to serve large enterprises like Dell and SONY. That company, Lithium Technologies, now powers social customer experience for hundreds of companies around the world. Lithium’s customers—brands like SONY, Best Buy, and Caterpillar—now have gaming in their social DNA.

Social customer experience takes more from gamers than just technology: Much of the knowledge and expertise in managing online communities came from gaming too. Meet a Fortune 500 or global brand’s community manager and you’re likely to have met a gaming enthusiast, gaming site moderator, or admin. Gamification, then, is not something new being added to customer communities; it’s been there all along.

Elements of Gamification

Today, it seems like everything is being gamified. In 2013, the City of Chicago gamified the city parks. Visit a park, get a badge. Collect them all! And people did just that.

The city’s goal was to help citizens discover and use all the great park resources—beaches, pools, tennis courts, nature paths, and so forth—in America’s third largest city. The higher purpose was to promote both civic and individual health. Whether you believe that people need such motivation to jump in a swimming pool, or that two pools are better than one, is beside the point. The point is that this example illustrates three common themes in gamification at its best:

- By adding an element of fun, it encourages people to do more of what they would like to do.

- At its best, it helps people achieve a goal that is meaningful to them.

- As a result, the brand—in this case the City of Chicago—achieves the business objectives associated with this particular program in an excellent and sustainable manner. The game encourages participation, and the game itself carries forward naturally as new parks and other points of interest are added.

In short, good gamification in a business context is built on human motivations that are intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, and that lend themselves to the future of the game itself.

But what does it mean to gamify a system? Specifically, what elements make a system gamified? A gamified system has one or more of the following four elements:

- Points

- Ranks or levels

- Badges

- Missions or journeys

Remember the video games you played as a kid? When you finished a game, you got a point score. If the score was high enough, you showed up on a leaderboard. Point scores accomplish the minimum that gamification should achieve: They make progress visible and measurable and thereby inspire efforts at improvement. The downside of point systems is that they are easy to manipulate, to game. Compared to other gamification elements, points can be harder to align with intrinsic motivations: Not everyone describes himself or herself as competitive, for example, so points alone do not make a game.

Again, back to the games you played as a kid: When you played more advanced games, you typically got another kind of reward. When you succeeded in negotiating a challenge, winning a battle, or solving a problem, you moved up a level. Levels or ranks are among the earliest and most fundamental elements of gamification. Not coincidentally, the difference between early message boards and later community platforms was built around rank: Community platforms adopted reputation systems—usually featuring ranks—that motivated people to continue to stay active over time.

Good rank structures for social customer experience share some common characteristics. First, they are flattering, not punishing; every rank title, even the lowest, should make the user feel good. (No “newbies” here.) Second, they are intuitively progressive; users will immediately know it’s better to be a king than a knight. By comparison, few will understand the hierarchical ordering of ranks like apple versus banana. Finally, they are progressively more difficult; going from level 9 to level 10 is much harder than moving from 2 to 3.

Well-designed social platforms allow you to combine online data with activities or credentials from the real world, like loyalty or education programs. As a result, ranks are often based on a variety of activities. And unlike a position on a temporary leaderboard, a rank is something lasting. Once you earn it, it’s yours. Some people put such permanent ranks in their email signature or LinkedIn profile; some even put them on their resume!

There’s a problem with ranks, however: As an individual you can generally have only one within any given social network. What if you want to give a user more than one reward, perhaps for a very specific activity, or for a limited period of time? That’s where the third element of gamification comes in: badging. With badges, customers can be rewarded for many different activities, typically with a distinctive graphic that appears on their user profile.

Badges can be awarded for any behavior that you want to encourage. In customer communities, badges are typically awarded for four things:

- Activity: Performing a particular activity at an exceptional level or for a specific period of time. Example: a badge for contributing 10,000 comments.

- Attendance: Being present or taking part in an event. Example: a silver badge for attending a user conference, and gold badge for attending 3 years in a row.

- Affiliation/certification: Earning or otherwise possessing a relationship with the brand. Example: a badge showing that you are an employee of the brand.

- Achievement: Accomplishing a set of activities. Example: a badge for viewing all the videos in a specific topic area.

Consider airline status, which may at first glance appear to be a rank. Airline status is really a form of badging. Look back at the previous criteria and you’ll see why:

- Airline status is typically earned based on a specific set of activities, with successive badges being earned as additional specific accomplishments—flights flown, for example—are accumulated.

- Status lasts only for a preset time. High-status flyers who participate less in the next year typically lose status—moving down to a lower status the following year.

By comparison, earning a “million mile flyer” designation is a true rank; once completed, it’s done and you own it forever. United Airlines’ MileagePlus program—not coincidentally voted the best frequent flyer program 10 years running—offers customers who achieve 1 million miles or more lifetime benefits; at 1 million miles, that customer is Gold for life (and of course can earn higher status in any given year). At 2 million miles, that customer is Platinum for life. At 3 and 4 million miles, additional lifetime levels are awarded.

What exists in addition to rank and badging? And specifically, what gaming provision rewards and motivates the absolute highest levels of participation? We’re glad you asked.

When a set of activities is significant enough, it qualifies as the fourth element of gamification: missions and journeys. Missions and journeys have been common in online gaming starting with the primitive text-based games of the 1980s, and they remain a powerful element in contemporary games. Missions and journeys align well with the basic notion of building a (gamified) community or other social application around passion, lifestyle, and cause.

Grand Theft Auto V generated more than $1B in revenue in the first three days after its release in September 2013. Why? Certainly the violent and salacious content didn’t hurt, but that’s actually not the success factor. Instead, the commercial success of games like Grand Theft Auto is connected to a basic human need to face a series of challenges and emerge victorious. We all want to win at something.

Now imagine harnessing the power of missions to the goals of your brand, your community, and your customer. Companies are increasingly thinking of their social customer experience channels not just as mechanisms to drive cost savings, satisfaction, and transactions but as platforms for driving change, learning, and transformation.

In this way, the fourth element of gamification—mission and journey—may ultimately be the most important. As we noted previously, gamification at its best helps people accomplish goals that are meaningful to them and that produce outcomes aligned with your business objectives. Things that have meaning are often hard and require commitment; therefore, missions and journeys, with their built-in difficulty, are an ideal vehicle for building social brand advocates.

Loyalty, Location, and Mobile

You may have noticed that the discussion about ways to earn a badge was not limited to activities that happen online. Your customers interact with you online and off, and it’s important to recognize this fact when you create your gamification strategy. Recognizing offline activities can be tricky, though unlike in the online world what happens offline isn’t always recorded and accessible. A visit to a shop or restaurant doesn’t show up on any server log; a purchase may be recorded at the cash register, but point-of-sale data isn’t always available to your social customer experience (SCE) systems. How do you unite your SCE efforts with your offline customer experience? Take a look at the following examples.

Foursquare: Mobile Game-Based Sharing

Beginning with phones that include GPS or similar location tracking, early applications such as Brightkite, Dodgeball, Loopt, and Latitude have made the simple act of being someplace talkworthy. (Just how talkworthy they are is, of course, left to the participants in any given conversation to decide!)

Each of these tools in some way traded on the value of knowing where others to whom you have connected are right now. Fast-forward to the contemporary location-based (aka, mobile) services like Google Maps and wearable products like Glass and Pebble that bring right-here, right-now interactions with brands within reach of a wide range of consumers. Add gaming, and stand back.

Early mobile applications included things like meetups, coffee shops, and dinner dates. Depending on your motivations, the ability to see where your friends are can be useful information. But beyond basic location awareness, these early applications didn’t do much. That was a problem.

Enter Foursquare. Foursquare combines location awareness with collective knowledge to produce an order of magnitude more useful (and more rewarding) experience. Using Foursquare, upon arriving someplace you check in. The GPS in your phone knows where you are, and Foursquare tells you what’s around you. Typically, you see the name of the place where you are and some others that are nearby, and you simply click Check In. As an additional nod to gaming, and recalling the discussions of badging and rank, Foursquare will evaluate your Klout score and let you know how you rank in your current location.

What makes Foursquare relatively more popular compared with earlier mobile check-in applications is its game-based functionality. As you check in, you accumulate points. Check in someplace new and add that venue to the Foursquare database—there’s a form for this right on your phone-based app—and you get six points. Even better, hit three places in the same day, and you get a Traveler badge. Go out on a weeknight, and you’ll earn the School Night badge. Co-author Dave does this too: Dave is a Level 10 Trainspotter (45 different stations), and has most every flight-related badge that exists. You can see your points and badges when you log in online or open Foursquare on your phone (see Figure 7-6).

Figure 7-6: Foursquare badges

Once you check in, you see a list of your friends also using Foursquare who are nearby, along with tips about the place you’ve checked into. The tips are one of the first big-value adds of Foursquare: Dave now advocates for the SBB (Swiss Rail) mobile app, which he learned about while climbing the Trainspotter ranks. Checking into a restaurant, you can see what’s good (or alternatively, what’s good that is right across the street). Checking in at a grocery store alerts others in your friends list that you’re there—and they can ping you to ask you to pick up some milk (since you actually know each other, the relative tolerance for such an imposition is known by both parties) and thereby save your friend a needless trip in the car.

Review and Hands-On

Applying social media principles effectively in business is both straightforward and challenging. It is straightforward because there is actually a process around which you can organize your efforts. It is challenging because much like the rethinking that occurs when applying social media in pure marketing applications, applying social technologies at a business level may require a redesign of the business itself.

Review of the Main Points

The five key trends covered in this chapter are summarized in the points that follow. Get these things right and you’re on your way to a solid implementation of social technology in business.

Real Time

Listen and engage with your customers, in and around the channels that they prefer. Immediate response is now the norm: Your customers expect a direct linkage to your company. Take advantage of off-domain social applications by listening to what is being talked about and connecting these people to your on-domain social applications.

Mobile

Real time essentially implies mobile: Think of mobile as the platform for “real-space” applications. In the way that real time means right now, at this moment, real space means right here, at this place. This is where your customers are heading. Meet them there.

Co-creation

Customer-driven design and lightweight customer participation (ratings and reviews, for example) lead to businesses built on co-creation models. Co-creation speeds innovation and positively links your business to the market.

Crowdsourcing

The follow-on to co-creation, crowdsourcing adds peer content, turning control over to customers and opening up business opportunities in the new sharing economy.

Gamification

By making it fun, by making it a challenge, and by making it a game, you can encourage your customers to participate in co-creation and crowdsourcing and orient these activities on a positive track that helps you build your business.

Hands-On: Review These Resources

Review each of the following, and ensure that you have a complete understanding of how social media and social technology are used.

- Dell Ideastorm

- Threadless

- Foursquare (You will need an account with Foursquare and a GPS-capable phone or similar hand-held device for this.)

- HARO

Hands-On: Apply What You’ve Learned

Apply what you’ve learned in this chapter through the following exercises:

- Assess the real-time capability of your organization. How long does it take you to respond to customers online? Can you reduce that time?

- Understand your company’s mobile strategy. Is your website mobile-friendly? Are there mobile apps that you could deploy? (Tip: Look at your competitors too!) This will help you understand whether you can integrate social with existing efforts or need to develop on your own.

- Prepare a short presentation using Threadless or a similar crowdsourced enterprise as the subject or any other collaborative business design application that you choose. Talk to your team about what makes the application work and how social technology has been built into the business.

- Looking at your own firm or organization, list three ways that your customers could collaborate directly with each other to improve some aspect of your product or service.

- Develop an outline for a business plan based on exercise 2 that involves multiple departments or functions to implement. Win the support of those people.