Chapter 4

The Social Customer Experience Ecosystem

This chapter concludes Part I and the introduction to social technology and its impact on customer experience. It pulls together the elements of the social customer experience ecosystem—profiles, applications, communities and forums, and more—and thereby provides the basis for understanding how to connect current and potential customers with the inner workings of your business or organization, where collaborative processes can drive long-term benefits.

Chapter contents:

- Social identities and profiles

- Social applications

- Social channels

- Brand outposts and communities

- The social ecosystem

Social Identities and Profiles

At the center of the Social Web and the shared activities that define it are the online identities of participants. Participants reveal their identities directly, by selecting usernames or populating profiles. They also express them indirectly, through the facts, experiences, and opinions they share. Observing and analyzing these identities is key to creating an effective social customer experience.

Not too long ago, when contributing anything online, people used pseudonyms. This was due, in part, to system limitations; usernames typically consisted of a single word, not a first name and a last name. Even if you were satisfied compressing your first name and last name into a single unit, character limits often prevented it. Concerns about privacy also drove the use of pseudonyms. After all, the Internet for the first time allowed an individual to create something that could potentially be seen by millions of people. Before then, only media companies had that power. People no doubt regarded their new power with some degree of caution.

Until the mid-2000s, the popular online social sites drew members, true enough, but those members were identified all too often with names—or handles—like blueangel12 or lotusflower. Then came social networks like Facebook. On Facebook and similar networks built around real identities people used their actual names. And that changed everything.

Facebook began as a way to share content—and hence experiences—with people you already knew: your classmates. As adoption spread, Facebook allowed members to add friends, family, and co-workers. The networks were private, limited to the people you chose and those who chose you. In that context, using your own name was obvious. And as a result, this collection of private networks grew very large—larger, in fact, than any social sites had ever become.

The arrival of massive real-name networks in a heretofore almost exclusively pseudonymous online world attracted surprisingly little comment among Internet watchers in media and academia. Those who did comment merely noted that real names might bring more civility to online discussions because participants would no longer be able to hide behind a masked identity.

From the perspective of social customer experience, however, the change is much more profound. Businesses could, as a result, identify their customers online and so could deliver more relevant offers and service to those customers. Just as important, they could identify those who are not their customers and begin to build relationships with them too. Real names presented an opportunity to bring the power of CRM to the Web, which must, by necessity, begin with a real identity.

Still, although hundreds of millions of people still interact using pseudonyms online every day, current trends suggest that real-name participation will continue to spread, well beyond the private, semi-private, or ambiguously public-private places that networks like Facebook have become. Consider Twitter, for example, where even those who choose non-real-name handles typically also provide their real name in their profile and often a photo as well. Sharing your real identity is part of the online social experience.

Speaking of profiles, while usernames and identity are in flux, there’s no such confusion about profiles. Profiles are where people display the personal information they choose to share with others. Profiles include information such as name, city of residence, hometown, employer, personal interests, hobbies, and favorite brands and products. Often, they also display, in an activity feed, the user’s most recent contributions or actions on the Social Web. Today’s profiles give individuals plenty of control over who sees what on their profile. Though detailed personal information is (still) generally not available except to trusted friends or colleagues, almost any profile provides a business with a basis for understanding who is actually participating and thereby potentially connecting that person to your business.

The existence of user identities—whether a simple username or a rich profile—is, in this sense, what differentiates social platforms and applications from everything else on the Web. Other websites can still be interactive, of course, but the interaction is between the application and the user: navigate to a file, download a PDF, or place an item in a shopping cart. In each of these, the primary activity occurs between a user and an application and is designed to facilitate a specific task. Identity—beyond basic security or commerce validation requirements—is of relatively little importance in this context. Because the individual participant is steering the entire process and because this is typically a task-oriented transaction, the identity of the participant matters little.

In a social context, by comparison, the interaction occurs between the participants as much or more than it does (overtly) between a specific participant and the application or platform. In fact, the less the software gets in the way, the better.

The Profile as a Social Connector

The role of the social profile as a connector cannot be understated in business applications of social media. Following on the prior discussion, the social profile provides two essential social elements:

- A tangible personal identifier around which a relationship can be formed

- A framework for accountability for one’s actions, postings, and roles taken in the relationship that forms

Taken together, the significance of the profile is its central role in establishing who is participating. In any relationship, the more knowledge you have about a person, the more likely you are to trust and share. For businesses, it’s even more critical. By connecting a business with its customers—or a nonprofit with its members or supporters—social profiles form the basis for an accountable, productive relationship.

Profiles on social networks function somewhat differently from profiles on more specifically focused communities. Social networks are people-centric: The profile is therefore a critical element. Communities are content-centric: People become known by what they contribute. Accordingly, profiles have a more limited role in communities than they have in social networks. In social networks, people tend to share their tastes and preferences; in communities, the profile is mostly an activity feed. In communities, few people take the time to complete optional fields or upload pictures. So much so that, a few years ago, when community platform provider Telligent introduced a design that highlighted photos of users, sites were covered by the gray silhouettes that stand in for real photos rather than the colorful portraits Telligent had assumed would be posted. One user waggishly commented, “What’s with the ghosts? Halloween is over.”

Of course Telligent wasn’t wrong—just early. Photos of actual members are now common on social networks. The shifts in member behavior being driven by social networks are making their way into communities too. Just as real names are showing up more and more often, profiles with real data are starting to receive more attention.

Premiere Global: A Practical Example of Profiles

Dave witnessed the demand for and value of real identity in his work with Atlanta-based Premiere Global (PGi) on the implementation of a community for developers working with PGi’s API suite. The community was intended to bring independent developers and internal PGi experts together in a collaborative venue that would spur the development of new and innovative communications applications.

The PGiConnect Developers Community, shown in Figure 4-1, was built on the Jive Software community platform.

Figure 4-1: PGiConnect: profile completeness

Implemented for PGi by Austin’s FG SQUARED, Jive’s toolset could have been used right out of the box. One of the advantages of building on a platform like Jive, rather than developing a custom application, is the speed with which a fully functional community can be launched. But PGi saw the need for something Jive didn’t have. They were convinced that profiles could be a powerful force for bringing developers together. But they also knew that most community members never bother to complete the optional fields. Taking a page from LinkedIn, PGi’s digital agency had an idea: If they made profile updating easier and more obvious, they’d probably get more completed profiles. FG SQUARED developed a customer profile component for use with the Jive core toolset to do just that. Now when users visit the community, they get a quick indication of “what to do next” to help them move to the next level of completeness. In a nod to customer-driven improvement, Jive now includes this capability in its platform.

The Profile and the Social Graph

Recall the discussion of the social graph in Chapter 2, “The Social Customer.” Looking ahead, Chapter 11, “The Social Graph,” provides an in-depth treatment. For now, understand that the social graph includes the set of profiles that describe the members of a social network and the interactions, activities, and relationships that connect specific profiles on the Social Web. In perhaps the simplest view, the social graph defines the way one profile is connected to another, through a friendship relationship or membership in a group. Because the profile itself is tied to a person—however vaguely that profile may have been defined—there is a sense of accountability and belonging that translates into shared responsibility between those so connected. This relationship might be highly asymmetric: Blogger Robert Scoble’s individual fans may get more from him, as he is both an aggregator and an originator, than he gets from any one of them. Nonetheless, there is a set of rules and expectations that define these relationships and in doing so set up the value-based transaction and knowledge exchange that ultimately occurs between participants on the Social Web.

Understanding the construction of the social graph in the context of the profiles (people) collecting around your brand is essential in creating an organic social presence. Go back to the core challenge of effective participation on the Social Web: How do you participate without being branded as self-interested only? Your firm or organization needs to assert its relevance and then deliver through utility, emotion, or gained knowledge some sort of tangible value if it is to develop a strong bond with your customers that outlasts contests, advertising spending, and other direct incentives aimed at driving early involvement with the online social presence of the brand, product, or service.

What are the first steps in developing a social presence where this can happen? You go where your customers are, communities such as LinkedIn or Facebook, and create an appropriate place within them for your business or organization. As you work your way into these communities you’ll discover (or confirm) what or where you can add value. By participating, actively listening, and understanding and tracking influencers, you’ll see the relationships, interactions, and needs that exist within the community and intersect with the value proposition of your business or organization. That is your entry point and one on which you can build your presence.

Social Applications

In Chapter 2 we discussed the four basic building blocks of engagement: consumption, curation, creation, and collaboration. How do these processes happen online? They happen through social applications.

Whether a social network like Facebook or an online community like Autodesk’s, every social site is a collection of applications that allow users to interact and share. These applications fall into five basic categories:

- Discussions

- Articles

- Assets

- Metadata

- Activity streams

Let’s look at each category in detail.

Discussions

Two-way text-based communication is a fundamental element of social interaction on the Web. There are several social applications that help accomplish this type of interaction.

Forums were the first discussion application on the Web. As a result, the word discussion has become interchangeable with forums in the parlance of web professionals. The essential element of the forum is a discussion thread, typically a series of back and forth exchanges (or posts) between two or more users. A forum is a collection of discussion threads.

Comments are arguably the most common discussion application on the Web today. Comments are themselves discussion threads attached to an article or asset.

Messages are typically private texts exchanged between two individuals. Messaging is usually provided as a subsidiary feature in a set of social applications and is often called direct or private messaging.

Chat is typically discussion that is conducted among users who are online at the same time. It is sometimes referred to as a synchronous application, as distinguished from asynchronous applications like forums, comments, and messaging.

Needless to say, the boundaries between these applications can be fuzzy, particularly the boundaries between messaging and chat, depending on the constraints or affordances the application offers with regard to public versus private, individual versus group, and synchronous versus asynchronous.

Articles

Articles, like discussions, are content contributed by users. They are distinguished from discussions primarily by length and format. Discussion posts tend to be short and freeform; articles are longer and typically must conform to a format or structure specific to the type of article. Articles almost always permit comments to be posted in response. Following are a few examples.

Blogs are articles that are presented in order of date of authoring and often (though not always) address a subject of current interest: Most bloggers post today and things that are relevant today. They are usually written from the point of view of an individual author rather than a corporate identity as might be the case for the About Us page on a company website.

Wiki pages are articles usually written collaboratively by one or more authors and capture a subject in detail. They usually include links to other pages and often include assets (see the next section) as attachments.

Knowledge base articles generally contain how-to information for readers trying to accomplish a specific task.

Status updates are brief articles of a timely nature, generally bearing on what the author is feeling, thinking, or doing. These updates often relate to what the author is reading or viewing online and therefore contain links to social articles or discussions like those previously mentioned or articles and assets from official media sources.

Reviews are articles that consider and evaluate products or services that the author has personally used or experienced. Reviews used to be perhaps the most common type of social article on the Web, until social networks made status updates so ubiquitous.

Assets

Assets are items that exist in forms other than HTML text, such as videos, document files, images, code samples, and so forth. While text is still the most common social medium, images and video sharing are growing, spurred by the growth in smartphone use. And of course, video site YouTube and pinboard photo-sharing site Pinterest are among the largest social sites on the Web.

Metadata

Metadata is perhaps an arcane word to use for something so common: the assignment of scores, ratings, tags, or bookmarks to the content encountered on the Web. Sometimes the items rated are social, like marking a review on Amazon.com as helpful or not. Sometimes the items rated are not in themselves social, like giving a five-star rating to a computer printer. Regardless, both kinds of action are deeply social, since our action is visible to others, and they can and do use this information to make their own decisions about what to read, believe, or buy.

While large social sites exist purely for the purpose of rating customer experiences—think Reddit—we focus mostly on how companies are using metadata features to help gain the customer’s help in evaluating their experience and organizing the social content they contribute and use.

Activity Streams

You’ll often hear terms like newsfeeds, status updates, and activity streams used to describe the dynamic nature of social content and metadata as it flows between people on the Social Web. Of primary importance are newsfeeds and activity streams. Consider Wikipedia’s definition of an activity stream:

An activity stream is a list of recent activities performed by an individual, typically on a single website. For example, Facebook’s News Feed is an activity stream.

If you’re still confused about the difference between newsfeeds and activity streams—which get merged in this definition—you’re not alone. In the context of the Social Web, it’s important to distinguish between a newsfeed and an activity stream. A newsfeed doesn’t have to be social; you can get a newsfeed from any news or similar content website. An activity stream, by contrast, is always social and always composed primarily of entries composed by you for consumption by others. (We say “primarily” in recognition of Facebook’s suggested posts and Twitter’s sponsored tweets.) In this this sense, status updates—which are really links to the profiles or pages of other members in your chosen social network—are considered components of a feed. Here is a simplified definition:

A feed consists of links to the work or contributions of others; a stream consists of the actual content associated with those contributions.

In this book, we reserve the term feed for things like the list of links to others’ activities that might appear on a profile page, and we use activity stream to refer to a listing of your contributions and that of other members within your network so you can read them at a glance.

Social Channels

When you engage your customers on the Web, rather than providing random, isolated experiences, you are generally better served by organizing these touchpoints within defined social channels.

As used in business and particularly in marketing, the term channel refers to the way that a company provides products or services to customers. Businesses typically use many channels within their marketplace to convey information. They use marketing channels (for example, television advertising, billboards, and direct mail) to deliver marketing messages to prospects. They use support channels (for example, phone, email, or service people in the field) to provide service to customers. And they use distribution channels (retailers, wholesalers, value-added resellers, and so forth) to get their products into the hands of customers.

Needless to say, the Internet sparked a revolution in the channels employed by business. According to the Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB), in just its first decade of mainstream use, online advertising grew to exceed advertising on cable television and nearly exceeded advertising on broadcast television, a 70-year-old advertising medium. Now, yet another revolution is reshaping business channels. This revolution is driven by social technologies, through channels characterized by ownership.

When characterizing social channels, we distinguish them according to the ownership of the social channel itself. We call channels that a brand or business uses for its own purposes on-domain, citing the typical association of that channel with the company’s own Internet domain (for example, http://supportforum.mybrand.com). By comparison, we refer to channels built around online properties that someone else owns as off-domain (for example, http://facebook.com/mybusinesspage).

An off-domain social customer experience occurs on a social network or with an application that you participate in as a business but that you do not control directly; an on-domain social customer experience occurs within a platform or application that you directly control.

The following sections cover off- and on-domain channels in detail.

Off-Domain Channels

Recall the discussion of home base, outposts, and passports in Chapter 3, “Social Customer Experience Management.” There’s an important distinction between home base versus outposts and passports: Home base is on-domain while passports and outposts are both off-domain. Your home base is generally your website and the associated properties. Social applications used on your home base are ones that you choose, implement, and manage. You determine who the members are, what they do, and what rules they abide by. Outposts and passports, by contrast, are off-domain. Someone else chooses the applications; someone else manages the platform. You have a presence on their platform. That presence may be a branded space where you have some control over design and features, or you may simply be participating as any other named member, interacting but not controlling the environment.

Off-domain channels are the ones that most people think of when they say social media. And particularly, they think of off-domain outposts like Facebook and Twitter. Like other outposts, these networks permit firms to have their own presence, branded in some way. On Facebook, companies can develop custom applications that no other company on the network has. Companies can create their own look and feel and even create multiple Facebook pages to accommodate different objectives or support different products or brands. Companies don’t own the network, but they own the experience that they create within that network. Table 4-1 shows some of the major outposts used by companies along with their reported member bases. Keep in mind that registered does not necessarily mean active, real people. That’s a discussion for another day.

Table 4-1: Social customer experience outpost

| Site | Core Applications | Users (2013) |

| Activity stream | 1.15B registered users | |

| YouTube Google+ | Video Status updates Activity stream | 1B users 500M registered users 343M active users |

| Profiles | 238M registered users | |

| Instagram | Photo sharing Photo sharing | 130M users 70M users |

There are many more outposts that may be of interest to a company, depending on industry, location, or target audience. For example, if you’re in China, then Sina Weibo (500M users in 2013) is of greater interest than Twitter. Business-to-consumer firms rarely consider SlideShare (50M users) a priority, but for business-to-business use, SlideShare can be quite significant in its ability to generate leads.

Social passports are related to off-domain social outposts. Passports differ in many ways from outposts in that the largest outposts are relatively few in number, and most companies use the same ones, such as those listed in Table 4-1. Passports are extremely varied, range widely in size, and tend to differ by industry. Outposts permit you to essentially own a piece of the network, branding and (often) customizing it as you see fit. Passports permit you to participate but without a dedicated branded space. Instead, companies send their employees to participate in these spaces or contribute content. That content is branded but appears alongside content created by other users.

Whereas outposts can support very different kinds of businesses, passports tend to be more industry specific. Intercontinental Hotels Group (IHG) can use Facebook as an outpost as effectively as Verizon Communications can. However, when looking for a passport, Verizon wouldn’t use TripAdvisor, any more than IHG would use the community at Broadbandreports.com. Microsoft and HP might each invite the other to participate in their social channels as a passport; American Idol and Caterpillar would not.

For all these reasons, there is no list of major passport sites. However, in Table 4-2 we provide examples of representative passport sites by industry.

Table 4-2: Example passport sites by industry

| Site | Industry | Focus |

| Broadbandreports.com | Telecommunications | Cable TV and Internet services |

| CrackBerry | Mobile devices | BlackBerry phones |

| FlyerTalk | Airlines | Air travel and airline loyalty programs |

| TripAdvisor | Travel and hospitality | Hotels, restaurants, travel destinations |

On-Domain Channels

Accepting that social applications are an adjunct to social networks and online communities, the starting set of applications—support forums—is built around the white-label social technology platforms offered by more than a few software providers. As used here, white label means a software application that can be branded to your specification but is otherwise ready to use. The platforms may be delivered as software for you to install or as a SaaS (software as a service) application from providers like Lithium Technologies, among many others. Table 4-3 shows a representative set of these platform providers.

Table 4-3: Social software—selected examples

| Provider | Core Strength | Examples |

| Lithium Technologies | Influencer identification, social customer experience | DISH, Comcast, Skype, Lenovo, Sephora |

| Jive Software | Internal collaboration | Premier Global’s iMeet |

| Salesforce.com | Ideation | My Starbucks Idea, Dell IdeaStorm |

| SharePoint | Enterprise workflow | KraftFoods.com, content management |

| Small World Labs | Niche communities | American Cancer Society |

| Socialtext | Enterprise collaboration | TransUnion, internal employee collaboration |

On-domain social applications built using the tools referenced in Table 4-3 are designed to facilitate accomplishing something in the context of a shared or collaborative goal and thereby to provide a specific and generally visible value to a given group of participants. And because these are on-domain applications, this activity occurs on your site, where you can manage and build on the relationships that result.

On-domain social applications are rooted in the task orientation of customers but then extend beyond that into more general social activities: Customers seeking assistance with printer support on the HP support forum may end up sharing stories about the events leading up to the pictures they wanted help printing. By delivering a service and then encouraging people to share their results, you create interpersonal relationships. In this way, on-domain social applications drive their own longevity and usefulness.

This is a very beneficial attribute when you are trying to encourage repeat visits and you don’t have an unlimited supply of funds to make up for organic interest and participation.

There is another aspect of social application design that warrants attention. A utility-oriented application by itself is not social. This means that unless you design your social application to be a part of the larger social framework—the ecosystem—in which your audience spends time, you’ll end up with an island.

What makes the social application social is its connection to the participants’ communities. For example, if a customer is interested in tips on how to enhance photos, a FAQ built out as a wizard-style assistant can suggest filters and related techniques. That will earn you one visit. But if you also add photo sharing and add the ratings or collaborative features to that same application, the resulting social interaction around the photos will earn you repeat visits and word-of-mouth that drives membership in your on-domain social application when the original member posts those photos and invites friends to your site to comment.

Manage On- and Off-Domain Activity

Deciding how to implement and manage on- and off-domain social sites can be difficult. Both are valuable, but for different reasons. Off-domain social networks like Facebook can be a significant source of traffic. On-domain social applications like support forums or product ratings and reviews can significantly enhance the customer experience and thereby enhance business results. Connecting on- and off-domain activity is therefore an area where you’ll want to dig in.

Consider the following use case: You’d like to manage off-domain activity—respond to people talking about or to you on social networks—and then draw some part of this traffic toward your on-domain support forum. But how do you accomplish this? The tools you may need to manage and measure interactions to the level of speed and quality you prefer may or may not be available within the native toolset on either or the off-domain network or within your on-domain application.

An entirely new category of tools has emerged to equip companies to get the most out of their off-domain social network outposts. Though many of the tools in this category reflect the relative immaturity of social networking itself, the newest tools support a broad range of social activity management. In the early days of social networks, companies focused more on listening than on engagement, so the early tools were good at listening but not so good at doing anything else. Now, it’s the demand for response that is central.

Customer support teams in particular were poorly served by tools originally designed for the very different objectives of the marketing organization. This situation is changing for the better as companies once struggling to engage and respond using a marketing platform take advantage of the newer social customer care platforms purpose-built for enterprise-class engagement. Table 4-4 lists some of the most popular tools used by companies today for listening, publishing, and social engagement.

Table 4-4: Social network management tools

| Company | Product | Focus |

| HootSuite | HootSuite | Social engagement |

| Lithium Technologies | Lithium Social Web | Social support and engagement |

| Salesforce.com | Buddy Media | Social publishing |

| Salesforce.com | Radian6 | Social listening and engagement |

| Spredfast | Spredfast | Social publishing |

| Sprout Social | Sprout Social | Social publishing and engagement |

Build a Vibrant Presence

Importantly, the social applications are not necessarily communities per se, though some amount to as much: They are more generally enablers of an activity or outcome that is useful to the members of a community with which an application is associated. Simply put, and critical to understanding how to build an effective social presence, this means recognizing that most brands, products, or services cannot support a community by themselves.

Why not? Think about the products that you use, the organizations that you support, and the real-world community around you. What among them constitute the things you think about daily and regularly and that you obsess over? These—and only these—are the things that are candidates for long-lived, organically developed communities.

Despite a lot of time and effort spent to the contrary, some brands, products, and services still do not command sufficient daily mindshare to sustain a community of their own. To see why this is so, make a quick mental list for yourself of the real-world organizations of which you are a member. The typical individual has one, three, perhaps five, or even a few more organizations. After that, most people run out of bandwidth, that is, the combination of an individual’s time and attention. There are only so many social organizations one person can effectively participate in. Online it’s no different: How many social communities can you really belong to? More importantly, how many will you actively participate in? For most, the answer is surprisingly similar (or perhaps not surprising at all) to the capacity for participation in real life.

Against that, ask yourself how likely you are to join a deodorant, toothpaste, or laundry detergent community. Yet, more than a few consumer goods brand managers have undertaken to build just these types of communities. Make no mistake: As long as the advertising spending is happening, people join, take advantage of offers, and maybe even engage in light social activities. But understand that membership is being driven by ad spending and not organic social interaction. Organic growth—versus ad spending and incentive-driven growth—is what you need to build long-term participation in a community.

This is not to knock awareness communities or the application of social media technology to drive awareness. These communities may well be important parts of overall awareness and marketing programs and often do deliver on some of the surface promises of the Social Web. Content consumption certainly happens, and to an extent curation—people voting or ranking what they see or do in these communities—may also be happening. But above that, in the more important behaviors of content creation and collaboration, activity generally starts to drop off. And as noted, when the ad spending stops, the community generally stops growing as well.

Think back to the laundry detergent site, and set aside the media-driven awareness uses of the site. How might this site look if it were to be built as a social application?

The typical laundry site probably has a stain-removal chart, right? There is clear utility value in knowing what types of pretreatments are effective on what types of stains. To this end, there are literally dozens of these types of sites. The problem is, specific products can be recommended for all sorts of reasons, and among them is because someone paid for the recommendation. This is, of course, the underlying issue with traditional and marketer-driven communications versus social or collective/consumer-driven communications. As a consumer, the only thing you know is that the marketer is trying to sell you something. The rest is based on the combination of brand reputation, your experience, and the shared experience of those you trust.

Enter social media, part one. The first element of the social application—and the first use of the engagement processes associated with it—is curation. Consumers are often more candid (issues of transparency and disclosure noted) in their reviews than marketers. Reviews are part of the solution, and the reviews of reviews go further and help others interested in the specific product or service to sort out and make sense of specific reviews by identifying those considered most helpful.

The contemporary social application takes it one step further: Building on the connectivity afforded by social technologies, the social application makes its results available to others, outside of the social application itself. In the context of the present example, where the basic consumer-driven reviews on the laundry site makes relevant information available to people who visit the site, the well-connected social application makes the results of trying a specific solution available to everyone. This can dramatically impact the spread of useful information (and sometimes not-so-useful information from the brand’s point of view).

Here’s an example of how this might work: Suppose someone discovers a particular stain-removal technique to be useful and posts this onto the stain-fighting social application. The application then sends a message to Twitter—with the contributor’s explicit permission—alerting the contributor’s followers that an effective stain-removal technique has been found. The member’s social graph takes over from there, spreading and amplifying the underlying consumer-generated content.

In this example, not only has the social application shown the customer how to better use a cleaning product, but it has encouraged the customer to post a new review and then facilitated its sharing through that customer’s larger (online) social community. Now those friends of friends have this information, and if confronted with a similar stain, or queried by someone they know, they can point back to the original source and benefit from it. This is how information traverses the social graph and adds value to participants.

Central to the social customer experience is the act of sharing, facilitated by the connectedness of the application to the communities around it. This is what creates the real value to a marketer. Sharing has a significant impact on the spread of positive (or negative—watch out!) information that amplifies and drives marketing at no cost beyond the construction of the application and its maintenance. Miss out on this aspect of social applications—build a social application that is more like an island than a shared space—and you will surely decrease the potential return on your investment.

The GoodGuide app shown in Figure 4-2 is a customer-driven, shared, and socially connected shopping application, available for both Android and Apple smartphones. GoodGuide is a great example of how the Social Web is beginning to exert an impact on business units within the enterprise outside of the marketing department. GoodGuide is a business application built around the social customer experience. Read on to see how it works.

Figure 4-2: GoodGuide

Mobile applications for smartphones that scan a barcode and present pricing data and customer reviews are common. When Dave was looking for a portable spin-style toothbrush in Target, he was confronted with over two dozen competing models of semi-disposable, single-user (versus family applications) brushes in the under-$5 category. Dave recalls the experience, “I had zero information other than “Buy me!” to go on. So, I used my Android-based smartphone to scan the barcodes, right there in the aisle. Sure, I got a few odd stares (normal for me), but I also got access to independent product reviews, instantly through Google’s shopping guides. Based on the combination of independent reviews and manufacturer’s information, I made my decision.” This was a classic use of social media in a business (commerce) context. For the most part, as a consumer Dave was working with the marketing data, evaluating things like price and promoted feature set, and then extending this with a mix of company and consumer-generated product reviews.

GoodGuide moves beyond this core review data, which is now largely considered cost-of-entry for consumers nearing the point of actual purchase. It also moves well beyond the marketing department and into the core values and purpose of the business itself. GoodGuide serves up health, environment, and societal impact ratings: A score of 10 on Society, for example, means the product in consideration is offered by a manufacturer with responsible investment policies, equitable hiring practices, an appropriate commitment to philanthropy, and a firm policy toward workplace diversity. As noted, this goes way beyond the purview of the marketing and communications departments.

Compare this with ratings, reviews, prices, and features. Investment policy, hiring practices, and environmental impact are decidedly outside the marketing domain in most businesses, although social business certainly suggests that this is likely to change. Customers are now armed with a much more holistic view of the countries of origin, manufacturers, suppliers, retailers, and even taxing entities that make up the entire purchase chain. This is all part of the decision-making process now.

Social applications such as GoodGuide bring visibility to the larger business process and with it an entirely new set of considerations that reach across departments and functions. If you are looking to enable more of your organization to create favorable conversations, this is the starting point.

The combination of on-domain social applications—your support forums, communities, knowledge stores, and similar—along with your off-domain presence in places like Twitter, Facebook, and Google+ can be quite powerful. When compared with building a stand-alone community around a brand, product, or service—go back to the toothpaste or deodorant community examples—a highly integrated social implementation results in a more widespread and free-flowing interchange of information between consumers and your organization. This, of course, brings up one of the aspects of the Social Web and its use by consumers that causes some marketers sleepless nights: the prospect of negative conversations circulating outside of their control but very much visible to potential customers.

Unfortunately, there is no easy answer when negative conversations arise, unless you consider fixing the problem at its source as being easy. Take time to review the “Respond to Social Media Mentions” sidebar in Chapter 1 as you develop your basic response process.

Here too, however, social technology provides relief. Support forums—properly managed—can go a long way toward improving the customer service experience (lowering the incidence of negative conversations) and reducing the costs of customer service delivery in the process. At the very least, support forums can be used to quickly spot common problems so that root-cause corrective action can be taken. Once the problems are corrected, the very customers raising the objections can be connected back into the process, creating a more favorable relationship.

Here again you see the larger connection between the Social Web and business: Beyond social media marketing and monitoring conversations, the integration of social applications that connect your business to the larger (customer) ecosystem provide you with the data, solutions, and basis for relationships that can help you fix what needs fixing and preserve what’s already working.

Much of what we just covered sounds simple—and in theory it is—but beware: Stepping up and actually implementing social customer experience management—directly connecting your engineers to your customers so that they can learn first-hand the pain points of customers—is challenging. That said, getting it right creates both a barrier to entry and a competitive differentiator that is difficult for slower-off-the-mark competitors to counter. If you move first, you get the advantage, and that can pay measurable benefits down the road.

Content Sharing

If support forums and similar social applications provide the connections between communities and your business, what is actually shared? Recall the engagement building blocks—consumption, creation, curation, and collaboration. Sharing first emerges in the curation phase of engagement as people rate the works of others in a public setting. Content creation, moving up another step, is almost universally done for the purpose of sharing.

Given this, social applications are typically built with the idea of members creating and sharing something. That something might be a rating, a photo, a solution, a story, an idea, or any number of other things. Expert communities are examples of sharing, wherein the content being shared relates to a specific problem posed by the community. On a different scale—and typically serving many times the number of people—support forums operate in this same way: Customers share problems in the hopes that by sharing they will find a solution.

Where the challenge in building a compelling social application is identifying the purpose of the application, the challenge in driving shared content is encouraging participation in the first place. The degree to which content is created and shared is almost purely a function of how easy it is to do and in the rewards for having done it. By rewards, we don’t mean cash; we mean social recognition. If someone is contributing quality content, ensure (as a moderator or through moderation policies or your reputation management system) that this person is recognized. Identifying and developing experts/influencers by watching content production and subsequent content sharing is one the keys to building a powerful social application.

Purpose-Built Social Add-Ons

Purpose-built add-ons—small software components that you add to increase or fine-tune application functionality—can provide a way to quickly implement social behavior. Like communities and social applications in general, these small, purpose-built software add-ons are designed to facilitate specific interactions within communities or between stakeholders. Contests, gifting, and content-sharing applications are examples of the kinds of things that you can add to your overall social presence to increase visitor participation. Further examples include advertising modules or “Share this with friends” blocks of code that you drop into a page template on your site to enable an external sharing or publishing service.

Table 4-5 lists a set of leading, proven, purpose-built social tools and add-ons that can be implemented quickly on Facebook and Twitter. They range from the simple—photo or video sharing—to the complex. Providers such as Friend2Friend and Buddy Media offer a range of full-featured add-ons that support contests, gifting, sharing, and more. Disclosure: Dave is a board advisor with Friend2Friend.

Table 4-5: Easy Social Solutions on Facebook and Twitter

| Provider | Core Strength | Examples |

| Buddy Media/Salesforce | Ready-to-use Facebook applications | Budweiser and Samsung Facebook tabs |

| Disqus | Comments and discussions | Droid Life (www.droid-life.com) |

| Friend2Friend | Social amplification | New Belgium Brewing’s Facebook Mobile Photo and Story Contest |

One of the more popular Friend2Friend-based solutions for New Belgium Brewing was based on people’s natural behaviors around sharing and story-telling. Figure 4-3 shows the campaign home screen inside Facebook.

Figure 4-3: New Belgium mobile story contest

What is notable about the New Belgium applications is how easy it is to build a compelling social program without building a complete community. Using the Friend2Friend platform along with Facebook, the app leverages the participant base that is already there by providing a small, well-defined activity that has meaning and relevance to a precise audience. The additional solutions shown in Table 4-5 from Buddy Media and Disqus are all great examples of promotional programs with a decidedly social element.

It is exactly this kind of smart approach to social media marketing and the larger area of social technology applied to business that makes obvious the way in which the Social Web is maturing. While Web 1.0 was typically implemented as competing islands (large portals going for traffic dominance in the hopes of selling ad space) Web 2.0 brought shared experiences and mashups (the “mashing together” of independent software apps to produce a complete solution) to the table. Savvy marketers picked up on this by building applications that connected their brands to the existing communities where their target audience spent time. The Social Web, the subject of this book, continues the shift toward shared versus competing experiences by integrating the audience and the business through a set of applications that facilitate collaboration, knowledge exchange, and consumer-led design.

Use Brand Outposts and Communities

It’s time to connect the basics to put in place the beginning of a framework for a social customer experience. Chapter 1 covered the basics of engagement. Chapter 2 covered the new role of the customer as a potential participant in your business. It also touched on the social graph and social CRM, highlighting tools that help you identify and build relationships with people who are talking about your brand, product, or service and influencing others in the process.

Chapter 3 framed social applications in the context of a business or organization that is being run based on direct collaboration with its customers. The basic interactions—creating relationships between community members and creating shared knowledge—come about through specific, replicable actions that can be designed into the organization itself.

In this section, the social behaviors described so far are applied in specific social spaces—think online communities here—where the actual interactions, discussions, and conversations take place.

Recall from Chapter 3 that communities are built around things like passions, lifestyles, and causes, the significant things that people choose to spend their time with. Sometimes, a brand, product, or service by itself does not warrant a community of its own; even when it does, that particular community is typically participated in by only a fraction of the total potential audience. For most businesses and organizations, the places where customers willingly spend time—often engaged in conversation about the business or organization—is a social network or online community that is dedicated not to brands, products, or services but rather to other people like themselves, with interests like their own.

So how do you participate as a business? Even more pressing, how do you get your customers to spend time doing real work with your team, contributing ideas and insights that will help you better define products or innovate in ways that will lower costs or differentiate you from your competitors? In short, how do you become part of the communities your customers or members belong to and begin to realize the promised benefits of social computing? You participate in the activities they are involved in—with full disclosure and transparency—in order to build the levels of trust that that will elicit their contributions of knowledge back to you.

To make the most of the Social Web, recognize two accepted facts:

- People often turn to their friends before they turn to a brand for help.

- The brand is, all other things being equal, probably in the better position to help.

So, the challenge is drawing from the places where people naturally spend time asking questions of each other and bringing them to a place where they can find specific help.

In an interview with Businessweek, author and blogger Jeff Jarvis noted three common mistakes that many companies make when adding social-media-based marketing programs to their overall communications mix. Of the three mistakes (see the “Jeff Jarvis: Three Mistakes to Avoid” sidebar for a complete reference), one in particular applies to brand outposts: The mistake is expecting customers to always come to you on their own for information. Jeff points out that it is essential for you to go to them instead. Look at the following list of the typical places where brand outposts are established: In each of these cases, you are going to them.

- Twitter Support Handle

- Google+ Business Presence

- Facebook Business Page

- YouTube Brand Channel

What defines a successful brand outpost? Given the shift from social engagement to advertising sales as the core business of most social networks, success is best measured in acquired attention, just as you’d measure success in any other advertising context.

Coca-Cola: Facebook

At about 10 million fans, Coke’s original outpost—its Facebook page—is one of the most successful examples of a brand outpost. Even more remarkable, it wasn’t created by Coke; it was built by Dusty Sorg and Michael Jedrzejewski, two passionate Coke fans. When confronted with a site built on Facebook but outside of Coke’s control, Coke chose to empower the fans who created the site and embraced the work they’d done.

Coke’s Facebook brand outpost, shown in Figure 4-4, is now a valued element of its online marketing program, so much so that in 2010, Coke deemphasized the use of one-off online campaigns in favor of extended social-media-based efforts, in part built around its brand outposts at Facebook and YouTube. In an interview at the time of the announcement, Prinz Pinakatt, Coke’s interactive marketing manager for Europe, said, “We would like to place our activities and brands where people are, rather than dragging them to our platform.” Coke may have additional opportunities for on-domain interaction, but they’re spot-on in meeting customers where they are!

Figure 4-4: Coca-Cola: Facebook brand outpost

Take a tip from Coke, Starbucks, Dell, and dozens of other brands: Approach the Social Web as a consumer and understand how you relate to it in that context. What do you find useful? Why are you using Facebook? What do you like about your business blog or internal company intranet? What utility do these provide and why are they useful to you? Apply the answers to these questions to the design of your social programs, and let them guide your participation in the online communities where the people you are interested in choose to spend their time.

The Social Ecosystem

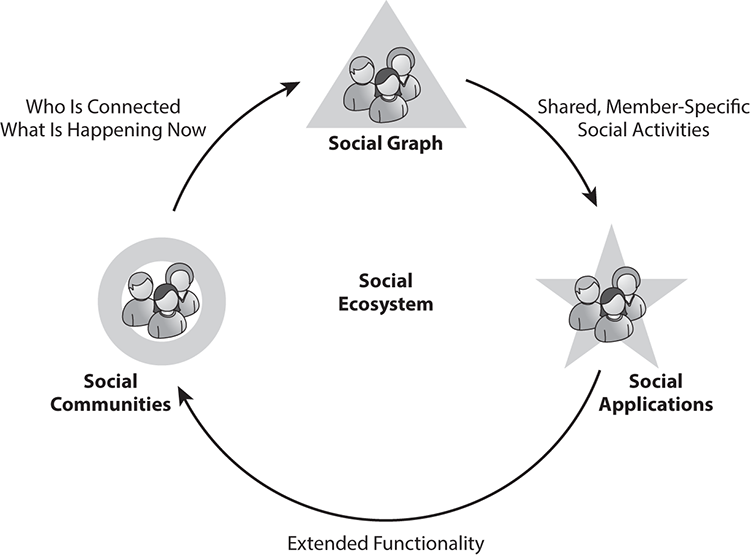

The social ecosystem, taken as a whole, provides three fundamental opportunities for understanding and leveraging the behaviors associated with collaborative interaction. These opportunities—the social graph, social applications, and social platforms—are shown in Figure 4-5.

Figure 4-5: The social ecosystem

The social graph—the connective elements that link profiles and indicate activities through status updates and the like—provides a framework for understanding who is related to whom, who is influential, where to look for potential advocates, and what is happening right now. This framework is important for participants: The social graph and the applications that rely on it facilitate friending and the sharing of content and experiences throughout a social network.

Behind the scenes, the social graph supports the programming techniques that allow social applications to discover relationships and to navigate the links that define them, suggesting potential friends or helping to spot influencers and generally providing an indication as to how participants in a social network are connected to each other and what they are sharing among themselves.

Social applications—extensions to the core capabilities of the social platforms and software services that support social networks—provide the additional, specific functionality that makes the larger community and platforms useful to individual participants. The Aircel recharge application shown previously in Figure 3-6 that extends the functionality of Aircel’s Facebook presence is an example of a smart, simple social application.

Social applications are also important in that they can facilitate overall membership growth. By incorporating specific applications into your community, that community becomes more useful to members, increasing the member stickiness and referrals in the process.

Finally, communities and other social platforms—built around passions, lifestyles, aspirations, or similar higher callings—provide the gathering points for individuals interested in socializing and collaborating in pursuit of the specific activities they enjoy together. These communities, support forums, and related social platforms are all places where the attention you have acquired on brand outposts can be collected and organized around specific topics, interests, or shared needs. By building a community around a passion, lifestyle, or cause and by looking for likely members among the participants in your brand outposts, you can foster and strengthen the relationships between the brand, product, or service and your customers and influencers. The progression from casual association (brand outpost) to collaborative participation and higher-level engagement (on-domain community) is thus enabled.

Importantly, the social graph, off-domain social applications, and your on-domain community applications drive each other. Take any one of them away and the value of business or organizational participation drops. This follows from the interconnections between these three. Without the social graph, for example, relationships between participants do not form and the community becomes transactional and self-oriented rather than social and collectively oriented. Without the communities and larger social objects (passions, lifestyles, and causes), the participants lack a sufficient motive to drive organic social growth. And without the social applications that extend the functionality of the core social platform, the activities within the community are limited to the broad activities of larger demographic groups, missing the highly engaging and very specific activities of small groups or even individuals. As a result, the social graph fails to develop in the way it would otherwise.

Review and Hands-On

This chapter showed how social applications connect members within communities and thereby facilitate social interaction. By behaving as a value-added member of these communities and then always participating from that position, you can establish a basis for trust. You’ll have to deliver, or course. Where fine print and high-speed voice-over can legally disclaim whatever expectations an advertisement may have set, in a social setting walking the talk is required. If you say it, you have to do it.

The benefits are significant: The combination of trust and relevance drives engagement and encourages people to share the information that leads to long-term success through the delivery of a superior experience. This applies within your organization—where the goal is instilling in everyone an attitude and empowered commitment to customer satisfaction—as well as outside, in the store, where as Sam Walton said, “Your customer has the answer.”

Review of the Main Points

Implementing social customer experience initiatives challenges many of the accepted norms in traditional top-down management systems. It requires rethinking some aspects of running a business and in many ways involves the not-so-obvious discipline of running your business as if you were a customer.

The tools and techniques covered in this chapter pull together the connection points between an organization and its stakeholders and in particular accomplish this in a way that facilitates knowledge sharing. The main points are these:

- Businesses connect socially to customers through visible relationships and useful, collaborative applications.

- Participation, knowledge transfer, and social activity can be measured.

- Friending and reputation management are important aspects of social behavior that lead to strong communities.

- Effective moderation and clear policies spur community growth.

- Brand outposts created within communities popular with your audience are ideal places to connect your business.

By recognizing the components of the Social Web and the ways that your customers or stakeholders use them, you can adapt your business or organization to a more participative, collaboration-oriented audience. This closer connection comes at a cost: Accepting customers as collaborative partners imposes an obligation to consider what they offer and to act on it. Not all businesses can do this, and even fewer can do it easily. That said, there is a clear process for accomplishing this, and there are plenty of cases and best practices from globally recognized firms that have been successfully building their own businesses using social computing and related techniques.

Hands-On: Review These Resources

Review each of the following, ensuring that you have a solid understanding of the concept being shown in the example:

- Brand outposts like Coca-Cola’s Facebook page are sometimes viable alternatives to one-off microsites and branded communities:

- New Belgium Brewing’s Facebook-based mobile photo and story contest taps readily available passions and interests. You don’t have to reinvent wheels to create great social media points of presence. Check this and other social marketing efforts based on sharing and content collaboration created by Friend2Friend for New Belgium Brewing:

- Clearly articulated policies create a strong platform for collaboration and the adoption of social computing:

Hands-On: Apply What You’ve Learned

Apply what you’ve learned in this chapter through the following exercises:

- If you use Twitter or LinkedIn, bring your personal profile up to 100 percent completion.

- If your office or organization has a profile-driven knowledge-sharing application, repeat exercise 1 for your profile on that network. Then, get three colleagues to do the same.

- List your favorite social communities, and describe an application that your business or organization might offer within that community. Connect it to your business objectives.