CHAPTER 10

How to Select a Security

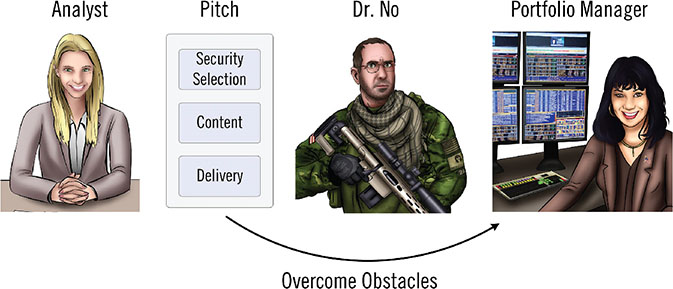

Because portfolio managers expect analysts to supply them with compelling investment opportunities, the analyst’s primary role is to find and present ideas that will outperform the market.

However, since the portfolio manager’s success depends on the investment performance she delivers, she will be extremely selective about which ideas she adds to her portfolio and will put any new idea under intense scrutiny to identify its flaws. The analyst must be able to defend her analysis if she is going to survive this gauntlet.

Portfolio managers are also extremely busy. They are inundated with information and new ideas throughout the day and are always short on time. To the portfolio manager, her time is a finite resource and most precious asset. Therefore, the manager will also be extremely selective in allocating her time and, if the analyst is given an opportunity to pitch her idea, the analyst must be quick, concise, and persuasive.

For these reasons, most portfolio managers will have their guard up concerning any new investment idea they are pitched. Imagine that in their mind, they have a highly alert, slightly paranoid, heavily armed sentinel to protect them from bad investment ideas and analysts wasting their time. We can call this guard Dr. No.1 This layer of protection produces obstacles that the analyst must overcome to get her idea adopted.

The first task is security selection. It is important to find an idea that fits the portfolio manager’s schema, which is a type of mental model comprised of the manager’s investment criteria. Most portfolio managers have an idea in their mind of the perfect investment (their schema), which is the target that the analyst is trying to hit, and experienced managers recognize a good idea by matching its characteristics against this ideal.

The Importance of Matching a Portfolio Manager’s Schema

Paul S. learned an important lesson about security selection early in his career from his Uncle Arnie that Paul has imparted to his students over the years. When speaking with former students years after graduation, it appears to be the one thing (sometimes the only thing) that many of them seem to remember. That sage advice? “If your boss asks you for a blue umbrella, don’t bring him a red one and then try to explain how it will keep him dry.”

Many rookie analysts make the understandable mistake of finding an idea that they like and then try to convince the portfolio manager to adopt it. This approach is generally a bad strategy. It is like trying to pound a square peg into a round hole. A better tactic is to select an idea that the manager will like because it will take a lot less effort convincing her to adopt it.

How should you determine what types of ideas the manager will find attractive? With the precision and persistence of a CIA operative, you will need to study the manager to develop a comprehensive profile of what characteristics they look for in the perfect investment. In other words, you must get inside their head and learn to think like they do.

We discuss in Chapter 5 the process by which an investor calculates their estimate of a stock’s intrinsic value, which is replicated in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 An Individual’s Process for Estimating Intrinsic Value

As Figure 10.1 shows, an investor makes observations, processes the information with a model that is influenced by his domain-specific knowledge, arrives at an estimate based on that analysis, and then takes action based on his conclusion. The investor’s domain-specific knowledge is a product of his experience and expertise, and the accumulated facts he has collected. To understand how a portfolio manager thinks, the analyst needs to reverse engineer the manager’s decision-making process to determine how he arrives at his estimate. This means the analyst needs to get inside the manager’s head to find out how his internal model works. Only then can the analyst figure out what types of investment ideas will grab the manager’s attention. Figure 10.2 shows questions to ask when reverse engineering the portfolio manager’s investment process.

Figure 10.2 Reverse Engineering the Decision-Making Process

Through many years of trial and error, a portfolio manager builds a mental checklist of investment likes and dislikes. As a result, there are opportunities that immediately pique his interest and others that provoke a visceral negative reaction.

In his “mind’s eye,” the portfolio manager has a vision of what the perfect investment looks like. The criteria he uses to judge potential investment opportunities are best thought of as mental templates of ideal or perfect investments. The manager uses these templates to judge new investment candidates quickly. The criteria in the templates allow the manager to recognize patterns and act as a mental shortcut to reduce the time and energy needed to make an investment decision. In formal terms, these templates are called schemas.

A schema is a simple concept. Close your eyes and think of an ice cream sundae. An image will pop into your head of your ideal sundae. This mental picture can be either a compilation of the good qualities of sundaes you have eaten over the years rolled into one or a memory of a specific sundae that you thought was perfect. Whenever ordering a sundae you will compare it subconsciously to the sundae in your mind to decide how closely it matches the ideal. For instance, if you are allergic to peanuts, then any sundae with peanuts on it will fall into the “bad sundae” schema template. On the other hand, if you like chocolate sauce and cherries on your sundae, then these likes fall into the “ideal sundae” schema template. We present a schema for a sundae in Figure 10.3.

Figure 10.3 Schema for a Sundae

Schemas are not static, however. They evolve over time as individuals are exposed to new facts and additional experiences. The new information is added to, and alters, the old schema. For example, assume you see a commercial on TV for Burger King’s bacon sundae.2 You might not have thought of this combination before, so you do not have that criteria in your sundae schema. You update your facts to include “bacon can be used as a sundae topping.” Your sundae schema is now changed forever as it will always include bacon as a possible sundae topping. Imagine that you go to Burger King to try one, and it’s awful. Your experiences have altered your “bad sundae” schema by adding a sundae topped with bacon to it. The next time you are offered a bacon sundae, your mind will automatically think, “Sundaes taste lousy with bacon,” and you will instantly reject it, as shown in Figure 10.4.

Figure 10.4 Bacon Sundae Is Rejected

This example shows how individuals subconsciously use schemas to identify patterns quickly and make decisions efficiently. Evaluating stocks is no different than evaluating sundaes, and many portfolio managers use schemas to size up new investment ideas quickly. For instance, if a new idea matches a portfolio manager’s well-established positive pattern, then he will consider it. On the other hand, if the idea does not match a positive pattern, it will be rejected. It is important to note that portfolio managers often have more than one investment schema. For instance, a manager might have a “turnaround” schema, a “new management that will cut costs” schema, a “spinoff” schema, or even a “slow growth, strong cash flow, major stock buyback” schema.

A portfolio manager’s schemas change as he is exposed to new facts and different experiences. For example, getting defrauded by a CEO with a mustache might result in the manager creating a new “companies who have CEOs with mustaches are bad investments” schema.3 There are also schemas within schemas. For example, a portfolio manager might have a few different schemas for CEOs that fit within a larger turnaround schema. Portfolio managers will have schemas of investments that worked out well and schemas for investments that did not. One manager might hate investing in toy companies because they were burned by one before, but love shoe manufacturers because they have made money with those companies in the past. Pitching a toy company stock to the manager will trigger their “toy company” schema and they will most likely shut down your recommendation immediately, although they will be quite receptive to a pitch for a shoe company as it triggers a schema that has previously worked well for them.4

A portfolio manager’s schema for the ideal investment is a little more complicated than their schema for the ideal sundae. Their investment schema contains two main sets of criteria, one based on the company’s fundamental criteria and the other on the stock’s valuation criteria. Fundamental criteria focus on the quality of the business, with factors that include, but are not limited to, the company’s industry, competitive position, capital intensity, growth rate, and quality of management. The fundamental criteria address the question, “Is this a good business?” The valuation criteria focus on the investment’s risk/return profile and address the question, “Is this a good investment?”

If the investment idea does not satisfy either the portfolio manager’s fundamental or valuation criteria, he will reject it immediately. If the idea satisfies the manager’s fundamental criteria but not his valuation criteria, he will listen with some level of interest and may make note to track the stock in the future (putting it on his “shopping list”), although, most likely, will not follow the recommendation to buy the stock. If the opportunity does not fit his fundamental criteria, but the valuation looks compelling, the portfolio manager might take further interest in the idea because of its potential return. If the idea satisfies both the manager’s fundamental and valuation criteria, he will clear his desk to move as quickly as possible to exploit the opportunity. We present the four possible scenarios in Figure 10.5.

Figure 10.5 Matrix of Fundamental and Valuation Criteria

The “shopping list” category in Figure 10.5 bears further explanation. Robert Bruce, a legendary value investor, who was handpicked by Warren Buffett to run the investment portfolio at Fireman’s Fund in the 1970s, explains that looking for stocks is like shopping for shoes. Bruce says he is always on the lookout for shoes to buy and often window-shops for ones he likes, although he usually waits for them to go on sale before buying them. He stated that he does the same thing with stocks. He is always on the lookout for stocks he wants to own, but only buys them when they go on sale. Because many other portfolio managers window-shop for stocks like Bruce, they will likely be interested in a new idea if the business fits their fundamental criteria as long as the stock is not too far from their valuation criteria.

In practice, fundamental and valuation assessments are made in parallel, although, for simplicity of explanation, we will discuss them serially. We start with fundamental criteria first and then explain how valuation criteria fit into the investment process.

Identifying a Manager’s Fundamental Criteria

To show the different facets of the portfolio manager’s fundamental criteria, we start with an example of buying a house. When someone goes house hunting, they usually have a good idea of what they are looking for in a new home and often have a picture in their mind’s eye of their dream house. The criteria in their dream house schema includes all the qualities or factors they desire, which is, essentially, a checklist.

Figure 10.6 Dreaming of the Perfect House and the Perfect Investment

Choosing a Stock Is Like Choosing a House

We illustrate the similarities of buying a home and buying a stock with a short story. Henry is a portfolio manager at the firm where you work as an analyst. Your job is to support the portfolio managers by bringing them ideas that will outperform the market. Simply put, you are trying to find stocks appropriate for them to buy for their portfolio. While you and Henry know each other professionally, you have not worked together closely in the past. One day, you bump into each other in line at the cafeteria, start chatting, and decide to have lunch together.

During the conversation, you discover that Henry is looking to buy a new summer home. You ask what kind of house he is looking for and he mentions several characteristics for his ideal home—five bedrooms, less than $15 million, tennis court, nice neighborhood, modern with a classic design, and priced below market. You tell Henry, “My good friend Ed Bogen5 is a real estate agent, and he was just showing me a new exclusive listing that might be perfect for you.” You pull up Ed’s listing on your phone to show Henry a few pictures of the house. He responds, “Wow, that house looks really nice.” You tell him a little about the house: five bedrooms, great neighborhood, on the beach, listed at $12.5 million, with a classic design and modern construction.

The house was presented as a new idea and Henry subconsciously—in the blink of an eye—put the house through his “dream summer house” schema to see if it matched his desired criteria. This process is shown in Figure 10.7.

Figure 10.7 Schema for Summer House

Since Henry found the house appealing and it fit his schema, at least on the initial pass, he decided to call your friend Ed to schedule an appointment to see the house.

Henry and Ed meet later that week to tour the house. The next morning you walk into Henry’s office to ask him what he thought about the house. He responds, “It is a beautiful house, but I passed.” You ask, “What didn’t you like?” He shrugs his shoulders and says, “I’m not really sure. Ed is a great broker and is very professional. The house he showed me is really nice, but it just didn’t feel right.”

You prod him a bit further. Henry mentions that while the house matches his preferences, is right on the beach, and in a really nice neighborhood, he didn’t like it, although he couldn’t put his finger on why that was the case. With a slightly puzzled look, he replies, “Maybe it was a little too dark inside.”

You return to your office a bit perplexed and think to yourself, “Hmmm. I am a bit surprised. The house seemed to be the perfect match for him. He said that it had all the things he was looking for; I wonder why he didn’t like it?”

The following day you bump into Henry in the cafeteria. You start chatting and decide to have lunch together again. During the conversation, you find out that Henry just received an inflow of new capital into his midcap value fund and is looking for new investment ideas. You ask what kind of company he has in mind. Henry tells you his ideal investment—a market cap between $2 billion and $10 billion, undervalued, and a stock that has underperformed the indices in the past year. He generally avoids companies in the financial or biotech industries. He says he likes companies with analyst coverage, that have strong competitive positions and good capital allocation. He also likes companies with a P/E ratio below 20 and a five-year growth rate of more than 7%.

You tell Henry, “I know a company that might be a perfect fit. It’s Williams-Sonoma.” You pull up Google Finance on your phone and show Henry the company’s financials. He responds, “Wow, that stock looks really attractive.” You proceed to tell him a little bit about the company: “The market cap is $5.2 billion and the stock has a P/E ratio of 17. The company has generated 5-year growth of approximately 7%, the stock has trailed the index for the past year, and the company has a strong competitive position.” You give Henry a copy of your research report on Williams-Sonoma and he promises to read it later that day.

You walk to his office the next morning to ask him what he thought of the idea. Henry responds, “It’s a good idea, but I’m going to pass.” You then ask him what he didn’t like. He shrugs his shoulders and says, “I’m not sure, it looks like a good company, but I don’t feel that compelled to do any more work on it.”

You prod Henry a bit further. He admits that while Williams-Sonoma fits his investment profile based on the company’s financials, that the business has high returns on capital, and the stock looks undervalued, the idea is not compelling to him, although he could not put his finger on what he did not like about it. Henry then replied, “Maybe it’s that most of their sales are domestic.”

You walk back to your office a bit perplexed and think to yourself, “Hmmm. I am surprised. Williams-Sonoma seemed to be the perfect idea for him. He liked the company’s financials. The company has a strong competitive positon and consistent revenue growth rate. The stock is cheap and they have had great capital allocation. I wonder why he did not like it.”

What Went Wrong?

To figure out where the idea went wrong and why Henry rejected it, we will conduct a review on the recommendation. We will start with the summer house first to see if we can gain insight into how Henry makes decisions and then apply those insights into the stock recommendation.

To start, we need to gather the criteria that Henry gave you for his dream summer house, as shown in Figure 10.8.

Figure 10.8 Stated Criteria for Summer House

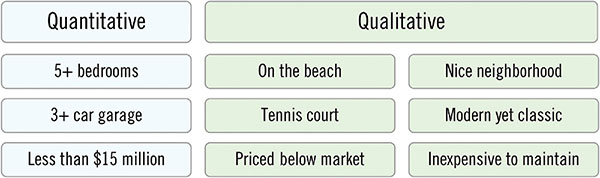

We can parse the criteria into different categories to diagnose why Henry passed on the house Ed showed him. At first glance, we see that some of his criteria are quantitative and some are qualitative, as shown in Figure 10.9. That seems like a good place to start the discussion.

Figure 10.9 Criteria Parsed into Quantitative and Qualitative

The quantitative criteria are items that can be objectively measured. These items are numerical and can be reduced to hard numbers. They are also go/no go–type criteria. If the house doesn’t match the numerical criteria, it will be eliminated from further consideration. For example, if the house has two bedrooms, it is clearly not a match and Henry will not spend more time looking at its other attributes. There is no point in suggesting potential houses that do not meet Henry’s qualitative criteria because he has been clear in what he is looking for in a new summer home and will reject them outright. The summer house you suggested met all Henry’s quantitative criteria, as shown in Figure 10.10, so that is clearly not where the problem lies.

Figure 10.10 Objective Quantitative Criteria Satisfied

We evaluate the qualitative criteria next. We see that the qualitative criteria fall into two broad categories: objective and subjective. The objective qualitative criteria are binary—yes or no–type filters—and the house either matches them or it does not. Three of the six qualitative criteria Henry gave you are objective: The house must have a tennis court, be on the beach, and priced below market for him to be interested. This analysis is similar to the quantitative criteria in that it is straightforward to see whether the criteria are met. For example, if the house isn’t on the beach, it is clearly not a match for Henry, and he will not spend more time considering the house’s other features. It should be easy to see that a potential house needs to meet these qualitative factors to keep Henry interested. Again, there is no reason not to meet this set of criteria when recommending a summer home because Henry has been specific about what he is looking for.

What about the other three qualitative criteria? We saw that there were hard numbers with the quantitative data. We also saw that it was relatively straightforward to determine whether the house met certain qualitative data, such as being on the beach or priced below market. It is much harder to determine if the house matches the remaining three criteria Henry stated because they are less clear in their meaning. Henry said he wanted the house to be in a nice neighborhood, but how does he define nice ? He wanted the house to be modern, with a classic design, but what is his idea of modern, or classic, for that matter? As the saying goes, beauty (or niceness in this case) is in the eye of the beholder. While you might be able to rank niceness on a scale of 1 to 10, it will remain a subjective measure. One person’s 10 can be quite different from another person’s 10. We split the qualitative criteria into two subcategories—objective and subjective—as shown in Figure 10.11.

Figure 10.11 Objective Versus Subjective Criteria

Did the house match Henry’s qualitative criteria? Obviously not, or he would have continued to be interested in it. The question remains, where did the recommendation go wrong?

As we see in Figure 10.12, it appears that the subjective qualitative criteria were the culprit in Henry’s rejection of the recommendation. When you had lunch with Henry, you thought you had a good idea of what he wanted when he listed his requirements. However, by a process of elimination, we can determine that for some reason the house didn’t meet Henry’s subjective criteria. Maybe the house wasn’t modern enough? Maybe it was too expensive to maintain? Most people would think the house is located in a desirable neighborhood, although it appears that Henry doesn’t agree.

Figure 10.12 Subjective Criteria Not Satisfied

The problem is that Henry merely stated his subjective criteria, such as nice neighborhood, without fully defining them. While you thought you understood what Henry meant when he said “nice neighborhood” and “inexpensive to maintain,” now you are not so sure. Perhaps you should have asked Henry more questions, such as “How do you define a nice neighborhood?” We might conclude that if you had asked those additional questions, you would have been able to better determine if the house was a good match for Henry. However, Henry must be able to explain his subjective criteria for you to fully understand what he is looking for in a summer house. The problem is that when pressed, Henry might not be able to articulate the definition of his criteria, even to himself.6

You then remember that when pressed, Henry said, “Maybe it was a little too dark inside?” You think back to the criteria that Henry gave you and realize he didn’t mention anything about sunlight. You walk over to Henry’s office the next morning and ask if there was anything else he didn’t like about the house. He says, “I thought about it as I was driving home last night. The property taxes were a little high, the house didn’t have a cobblestone driveway, and I’d like to be closer to town.”

You think to yourself, “Hmmm. He didn’t mention any of those things at lunch. Had I known, I wouldn’t have suggested the house.” This new insight highlights another type of criteria—Henry’s unstated criteria. Now that the additional criteria are stated, you can add them to your list. Some of the new criteria are objective and the rest are subjective. You now have a much clearer picture of what Henry is looking for in a summer house.

When you add Henry’s unstated criteria to the list, as shown in Figure 10.14, you realize that your recommendation did not match the additional criteria, as we show in Figure 10.14. The new objective criteria are relatively easy to validate, although the subjective criteria remain problematic.

Figure 10.13 Unstated Criteria Revealed and Included

Figure 10.14 Unstated Criteria Were Not Satisfied

While finding Henry a house, and helping your friend Ed earn a fat commission, would be a nice favor to do, it will be much better for your career if you found Henry a new investment idea for his portfolio. Let’s evaluate Henry’s investment criteria in the same way that we evaluated his summer house criteria to see where your recommendation of Williams-Sonoma fell short. We list the criteria Henry gave you about his ideal investment in Figure 10.15.

Figure 10.15 Portfolio Manager’s Stated Investment Criteria

We need to parse Henry’s investment criteria into the different categories to diagnose what went wrong with the recommendation, like what we did with the summer house. Similar to the prior example, some of Henry’s investment criteria are quantitative and some are qualitative, as we show in Figure 10.16.

Figure 10.16 Parsed Quantitative and Qualitative Criteria

The quantitative criteria are all items that can be objectively measured. These criteria can be reduced to hard numbers. They are also go/no go–type criteria. Henry will reject the recommendation from further consideration if it fails to match his quantitative criteria. For example, the company is clearly not a match for Henry’s midcap fund if its market cap is $500 million. It is critical to point out that any potential investment idea pitched to Henry needs to meet these quantitative factors—there is no reason not to match this set of criteria. Williams-Sonoma met Henry’s stated criteria, as shown in Figure 10.17, so that is not where the problem lies.

Figure 10.17 Objective Quantitative Criteria Satisfied

Next, we turn to Henry’s qualitative criteria. We see that these characteristics fall into two broad categories. Some of the criteria are objective and binary—yes or no–type filters. The investment candidate either has that quality or not, which includes three of the six qualitative criteria Henry mentioned such as the company has underperformed the index and the stock has analyst coverage. This vetting process of the objective criteria is similar to the one we performed for the quantitative criteria and is easy to ascertain. For example, if the investment candidate is a financial or biotech company, it is clearly not a match for Henry’s fund and he won’t spend any more time considering it. There is no excuse for a potential idea not to meet these qualitative factors because Henry has been clear in what he is looking for in an investment idea.

The other three qualitative criteria are less clear. Undervalued? Good capital allocation? Strong competitive position? We cannot put a hard number on those factors. Value and quality are in the eye of the beholder because they are subjective measures. As a result, we can split the qualitative criteria into two subcategories, objective and subjective, as shown in Figure 10.18.

Figure 10.18 Objective versus Subjective Criteria

Did William-Sonoma match Henry’s subjective criteria? Obviously not or he would have continued doing work on it. Where did we go wrong with the recommendation? Once again, the subjective qualitative criteria appears to be the culprit in Henry’s rejecting the idea, as shown in Figure 10.19. We thought we had a good idea of what Henry wanted when he listed his investment requirements during lunch. He told us what we thought was exactly the kind of company he was looking for. However, by process of elimination, we found that for some reason Williams-Sonoma did not meet Henry’s subjective criteria. Maybe management’s capital allocation decisions or the company’s competitive position were not good enough, at least in Henry’s mind? Maybe the stock was not undervalued, at least by Henry’s standards? It seems like most portfolio managers would think Williams-Sonoma is an attractive investment idea, although apparently, Henry didn’t agree. But why not?

Figure 10.19 Subjective Criteria Were Not Satisfied

Now that we look through the parsed criteria, we realize that maybe you should have asked Henry more questions. How does he define undervalued and good capital allocation? Which other companies does he think are undervalued? You might conclude that if you had asked more questions, you would have been able to better determine if Williams-Sonoma would be a good fit for Henry’s portfolio.

The problem is that Henry merely stated his subjective criteria, such as “good competitive position,” without fully defining them. While you thought you understood what Henry meant when he first said “good capital allocation,” now you are not so sure. Henry must be able to explain his criteria for you to fully understand what he is looking for in an investment idea. However, when pressed, he might not be able to articulate his subjective criteria, even to himself. The challenge for you is that Henry will expect you to understand exactly what he means when he states his subjective criteria. And, unlike objective criteria, which are unambiguous, each person’s definition of their subjective criteria will be different.7

What about any of Henry’s unstated criteria? When you discussed the investment idea with Henry, he revealed additional, albeit, unstated criteria, when he said, “And, as I thought more about Williams-Sonoma, I was concerned that most of their sales are domestic; I’m looking for a company that is more global with at least 50% of their sales from outside the US. I like firms trading at a lower valuation than the industry, and the company’s management doesn’t own much stock.”

Some of the new criteria are objective and some are subjective, as we show in Figure 10.20. You now have a better sense of what Henry wants in a stock and will have a better idea of what kinds of companies to recommend to him in the future.

Figure 10.20 Unstated Criteria Revealed and Included

When we add Henry’s unstated criteria to the current list, as shown in Figure 10.21, you realize that your recommendation did not meet the additional criteria.

Figure 10.21 Unstated Criteria Were Not Satisfied

It is clear that the subjective criteria continue to remain problematic. You originally thought you understood what Henry wanted when he listed his investment criteria, although, with hindsight, you realize you didn’t. Henry passed on your recommendation because it failed to match all his fundamental criteria.

Henry’s objective criteria are explicit—he stated them clearly and his metrics were unambiguous. There was little room for confusion or doubt. On the other hand, his subjective criteria were open to interpretation. While Henry thought he was clear when he stated he wanted a company with a “strong competitive position,” the definition was not articulated well, making it almost impossible for you to match the criteria. To make matters worse, Henry also has a list of unstated investment criteria, some of which were also subjective. It is not that Henry is intentionally trying to make your life difficult by not stating these additional criteria; it is that he might have forgotten that these criteria were important or they might be subconscious and not easy for Henry to articulate.

Identifying a Manager’s Valuation Criteria

If we parse Henry’s investment criteria even further, as shown in Figure 10.22, we see that some of the criteria relate to the fundamentals of the business while others relate to the stock’s valuation. Criteria like “P/E below 20” are quantitative and objective, and are easy to understand. While qualitative, the requirement “valuation less than the industry,” is also straightforward to match—the stock either matches this criterion or does not. However, criterion like “undervalued” is subjective and often open to interpretation. Does this requirement mean the company has a dominant market position in the industry or the strongest product offering in the market? While the criterion is stated, it is subjective, therefore, its definition is unclear and significantly harder to satisfy.

Figure 10.22 Fundamental and Valuation Investment Criteria

Other Barriers to Adoption

As we discuss at the beginning of the chapter, because the portfolio manager’s success depends on the investment performance she delivers, she8 will be extremely selective about which ideas she puts in her portfolio. Consequentially, most portfolio managers put all new ideas under an intense microscope to identify any flaws. To survive this intense scrutiny, the analyst must be right with his analysis.

There are actually two sets of obstacles that the analyst must overcome. The first obstacle is getting past Dr. No, which the analyst must do just to get the portfolio manager to listen to his pitch. There is, however, a second, much more challenging obstacle that the analyst must overcome to get the manager to adopt his idea.

The analyst circumvents the first obstacle by matching the portfolio manager’s objective criteria. If satisfied, the manager will listen to the analyst’s pitch. However, the second obstacle is a more formidable barrier and guarded accordingly.9 The analyst will not convince the portfolio manager to adopt the idea unless it satisfies the manager’s subjective criteria.

There is no excuse for the analyst not to meet the portfolio manager’s objective criteria since they are usually stated clearly, well defined, and unambiguous. On the other hand, satisfying the portfolio manager’s subjective criteria is a much harder challenge to overcome.

It is important to note that getting a portfolio manager to listen to a new idea is much easier than getting her to adopt it. There is no risk in listening to the pitch, other than lost time, which is not insignificant. However, there is significant risk to the portfolio manager once she commits capital, which is the possibility of losing money or underperforming the market, as we discuss in Chapter 9. Therefore, for the portfolio manager to take action on your idea it must satisfy both sets of criteria, as shown in Figure 10.23.

Figure 10.23 Idea Adoption Requires Overcoming Objective and Subjective Obstacles

If you consistently fail to match the portfolio manager’s objective criteria, you will eventually lose your job, as it demonstrates that you do not seem to grasp the manager’s most basic investment criteria (simply put, not matching unambiguous stated criteria is inexcusable). Your failure to match subjective criteria will result in a low adoption rate for your ideas. You may keep your job, but you will never get promoted and rarely receive a bonus, and will likely become increasingly frustrated in your job.

Overcome Barriers by Learning How to Read a Portfolio Manager’s Mind

The two most problematic areas in understanding what stocks a portfolio manager will find appealing are her subjective and unstated criteria. How is it possible for an analyst to read a portfolio manager’s mind? You must learn to think how she thinks. How can this be accomplished?

The analyst should ask a lot of questions to learn what the manager’s criteria include. The analyst also should read the portfolio manager’s letters to investors; review any interviews they have given in Barron’s, on Bloomberg, or in other industry news sources; and listen or watch any presentations they have delivered.

Analysts can also review the manager’s holdings to see which companies she is invested in currently. Managers with more than $100 in equity assets or who own more than 5% of a company’s stock are required to make periodic filings with the SEC disclosing their holdings. These filings include 13D filings, 13G filings, and 13F filings10. An ambitious analyst might even do additional research on specific positions to see if he can determine the criteria used to make these decisions.

These information sources focus on current investments in the portfolio, while prior filings can provide information pertaining to past investments. However, because the analyst is trying to determine not only the portfolio manager’s objective criteria but also her subjective criteria, having a view into investment ideas that did not get adopted would offer additional valuable insight.

This concept is referred to as negative space in the art world. The art critic needs to analyze not only what is there, but also what is not there, to fully grasp all the information the image conveys. The critic sees aspects of the image he would have otherwise missed by doing this analysis. This insight is illustrated by Rubin’s vase, which is presented in Figure 10.24. The vase is clear in the image on the left, while two faces are revealed when focusing on the negative space in the image on the right.

Figure 10.24 Negative Space and Rubin’s Vase

Because most portfolio managers perform research only on companies that meet their objective criteria, rejected ideas provide additional insight because they somehow failed to match the managers’ subjective criteria. Unfortunately, none of the information previously discussed, such as the SEC filings or news media interviews, reveals the investment ideas that the portfolio manager researched, but decided not to pursue. It will be nearly impossible to have access to such information from outside the organization. The analyst will have insight into rejected ideas only if he works closely with the portfolio manager.

Another important exercise when researching a portfolio manager is to build a checklist of criteria that the manager uses to make her investment decisions and to listen attentively to all questions she asks during the research process. These questions often provide insight into the manager’s subjective criteria. The following list are questions an analyst can ask to gain insight into a manager’s criteria:

- Does the manager have a target range or minimum hurdle for the expected investment return?

- What are the manager’s market cap constraints? Large, small, mid, nano-cap, or mega-cap?

- What are the growth characteristics the manager looking for? Is slow growth okay, or does the manager insist on high growth?

- What is the manager’s preferred valuation metrics? Do they look at EBITDA multiples, P/E multiples, or earnings power value? Are they in search of deep value, value, growth at a reasonable price, or pure growth?

- Are there specific industries the manager focuses on or avoids?

- What geography does the manager prefer? Domestic or international? Developed countries or emerging markets?

- Does the manager insist that a company have a strong competitive position or be an industry leader?

- Is the manager receptive to contrarian investment ideas and turnarounds?

- Does the manager have a preference regarding management? Any requirements regarding corporate governance? How important is the management’s ability to allocate capital?

- Is the composition of the company’s shareholder base a factor? Does the manager like to be the “only footprints in the parking lot” (meaning very few investors looking at the company), or do they feel more comfortable if there are other well-known investors who hold positions?

- Is there a limit on a company’s financial leverage?

- Does the manager look for the possibility of financial engineering or other types of restructuring? Do they gravitate toward companies that are takeover or activist targets? Companies where there is the need for a spinoff or divestitures?

- What is the manager’s typical time horizon? Weeks, months, years, or forever?

- What are the characteristics such as concentration and turnover in the manager’s portfolio?

Other Communication Pitfalls

Other potential opportunities for miscommunication occur when a portfolio manager has conflicting criteria in his mind for what he looks for in an investment idea. The conflicting requirements will make it nearly impossible for a single idea to match all his criteria, objective or subjective. Making the situation more challenging, it is likely the portfolio manager will be unable to articulate all the criteria he has in mind simply because his list of criteria is long. Furthermore, his criteria may change depending on what part of the criteria appears most important to him at that moment.

Another potential area for miscommunication arises when the portfolio manager is vague with his criteria. There are subtle differences between unstated criteria and vague criteria. For instance, the manager may have a good idea in mind of what he is looking for in a new investment, but fails to communicate even the objective criteria all that well. This problem is not uncommon. Portfolio managers are inundated with information, and although the analyst may have asked specifically what criteria the manager is looking for in an investment, the manager may not have the time or the interest to make the criteria as explicit as the analyst needs to be effective in selecting appropriate investment ideas. And, sometimes, the portfolio manager may avoid the discussion intentionally because he does not want to be pinned down.

And, of course, the problem may not be the portfolio manager’s miscommunication. Instead, he may be explicit in stating his criteria, yet the analyst either hears something completely different or interprets the criteria incorrectly.

Improving Communication Is Crucial to Increase Productivity Within an Organization

As we have tried to emphasize throughout this chapter, the analyst needs to make sure he fully understand all the portfolio manager’s objective criteria and must carefully research and study the manager to better understand his subjective criteria. Nailing the subjective criteria requires observation and communication, and a lot of it.

The portfolio manager has several responsibilities in helping the analyst be effective in his efforts to find appropriate investment ideas. For starters, the portfolio manager cannot expect the analyst to be a mind reader. The manager needs to make sure the analyst understands all his objective criteria and be aware that his subjective criteria may not be obvious even to himself, much less anyone else. The manager should try to communicate as many details about his full investment criteria as possible and offer direct feedback when a new investment idea fails to match his requirements.

Whether pitching a stock for a job interview, a class, a stock pitching competition, or to a portfolio manager in your organization, the analyst will be challenged to understand the portfolio manager’s schema and match the manager’s investment criteria. It is impossible for the analyst to read the portfolio manager’s mind, and vice versa. This disconnect results in wasted time and mutual frustration. The fix is better communication, which leads to greater idea adoption and, ultimately, greater organizational productivity.

Gems:

- Portfolio managers use schemas to evaluate new investment ideas quickly. Any idea you pitch must match one of the manager’s schema.

- The portfolio manager’s schema contains two main sets of criteria: fundamental criteria, which are focused on the quality of the business, and valuation criteria, which are focused on the risk/return profile of the stock.

- The portfolio manager’s criteria are further segmented into objective and subjective criteria. There is absolutely no excuse for the analyst not meeting the portfolio manager’s objective criteria because they are usually stated explicitly.

- Assuming all the portfolio manager’s objective criteria are met, most pitches fail because they do not satisfy the manager’s subjective criteria, often because it is difficult for the manager to articulate these criteria fully.

- The portfolio manager will listen to a pitch if the idea satisfies all her objective criteria, but will not adopt the idea unless it satisfies her stated and unstated subjective criteria.