CHAPTER 11

How to Organize the Content of the Message

Your interview is tomorrow morning. Bright and early. You have done a lot of work and think you have a stock you will feel confident pitching. You have researched the portfolio manager you are meeting and built a dossier that a seasoned CIA operative would envy. You are confident you have his objective criteria nailed down and have a reasonably good understanding of his subjective criteria. You have done a lot of independent research and have developed a variant perspective, combining what you think is an informational and analytical advantage. Finally, you are confident that you have identified a genuine mispricing in the market and know what will correct it. You are as prepared as you could be for the interview.

When you meet the portfolio manager, how much time will you have? Probably not a lot. Maybe a few minutes before he gets bored and starts looking at his watch. Given this time constraint, how do you distill all that research into a persuasive pitch?

How to Capture and Keep a Portfolio Manager’s Attention

When determining what elements to include in your pitch, imagine that your house is on fire and you have only 30 seconds to evacuate. What three items would you take? Similarly, you need to think about the three most essential points you want to convey to the portfolio manager in your pitch.

Pitching a stock to a portfolio manager is not like pitching a stock in class or at a stock pitch competition, where you can drone on for 20 minutes, testing your audience’s patience as you drag them through your 30-page PowerPoint presentation. You cannot simply throw disembodied facts at the portfolio manager, hoping he will somehow make sense of them. The portfolio manager does not have the time, inclination, or patience to listen to what you have to say, put all the pieces together in a form that makes sense to him, and then weigh the validity of your investment idea. You are simply asking him to do too much work.

Building upon Judge Mansfield’s mosaic theory that we discuss in Chapter 8, we use an analogy of a puzzle. If you have done sufficient research, while a few pieces might be missing, you feel that you know what the completed puzzle will look like. You may have convinced yourself that the picture is clear, but now you must convince someone else. Most stock pitches fail because the analyst essentially tosses a jumble of pieces onto the table and says to the portfolio manager, “Here, you go figure it out.”

Imperial Airship by James Ng, redrawn with permission.

Even when more experienced analysts think they have provided the portfolio manager with enough information for him to see the complete picture and make an investment decision, the pitch often falls flat because they provide a picture with too many pieces missing. The portfolio manager needs to see the full picture to understand, comprehend, and adopt your idea.

Imperial Airship by James Ng, redrawn with permission.

To pitch an investment idea successfully, you need to show the portfolio manager as much of the picture as possible.

Imperial Airship by James Ng, redrawn with permission.

How should you use the limited time you have to paint a picture that the portfolio manager can understand? What do you say when the portfolio manager asks, “So whatta you got for me, sport? Why are you here?”

A typical pitch looks like the scene from the movie Wall Street,1 when a young Bud Fox finagles his way into Gordon Gekko’s office and, after sitting for hours in the waiting area, finally gets a few moments of Gekko’s time. Gekko says to Fox, “So what’s on your mind, kemosabe? Why am I listening to you?” In the movie, Fox pitches his first idea: “Chart breakout on this one here. Whitewood-Young Industries. Low P/E, explosive earnings, 30% discount to book value, great cash flow, strong management and a couple of 5% holders.” Gekko shuts him down, “It’s a dog. What else you got, sport?”

Unfazed, Fox immediately jumps to his second idea, “Terafly . . . Analysts don’t like it, I do. The breakup value is twice the market price. The deal finances itself, sell off two divisions, keep—” Fox is shot down again as Gekko interrupts him midsentence saying, “Not bad for a quant, but a dog with different fleas.” Fox gives his third idea:

- Fox:

- Bluestar Airlines.

- Gekko:

- Rings a bell somewhere. So what?

- Fox:

- A comer, 80 medium-body jets, 300 pilots, flies northeast, Canada, some Florida and Caribbean routes . . . great slots in major cities—

- Gekko:

- Don’t like airlines; lousy unions.

- Fox:

- There was a crash last year. They just got a favorable ruling on a lawsuit. Even the plaintiffs don’t know.

- Gekko:

- How do you know?

- Fox:

- I know . . . the decision will clear the way for new planes and route contracts. There’s only a small float out there, so you should grab it. Good for a five-point pop.

- Gekko:

- Interesting. You got a card? [then a long pause] I look at a hundred ideas a day. I choose one.2

This exchange is actually a common scenario in the investment business. The portfolio manager is busy and distracted, and you—the analyst—have only a small window of time to capture his interest. We have found that it is most effective to think about your pitch as comprising three distinctively different elements—a 30-second hook, a two-minute drill, and the ability to sustain five to 10 minutes of Q&A. Keep in mind that this structure is just a guide; not every portfolio manager operates this way. Oftentimes an impatient portfolio manager will interrupt the analyst and pepper him with questions only a few sentences into the pitch.

The first element—the 30-second hook3—must be simple, succinct, and extremely compelling to quickly capture the portfolio manager’s attention. Like Pavlov’s dogs salivating when the bell rings, your hook should trigger greed in the portfolio manager’s mind. If your hook is persuasive, the portfolio manager will subconsciously shift his weight forward in his seat as he leans toward you. Now, you have his attention, and he wants to hear more.

The goal of the hook is to motivate the portfolio manager to listen to your two-minute drill, which will present the crux of your pitch. The two-minute drill tells a story and lays out your main arguments. It should reinforce the attractiveness of the investment and draw your audience further into your pitch. The goal is to persuade the portfolio manager that the idea has merit, and if you pass the two-minute drill, you can expect to get a deluge of questions.

Returning to the movie—why did Gekko pass on Whitewood-Young and Terafly, but became intrigued by Bluestar? As we discuss in the previous chapter, when a portfolio manager hears a new idea, he will listen if the idea matches his objective criteria. However, he will only adopt the idea if it satisfies his subjective criteria.

Gekko clearly knew both Whitewood-Young and Terafly well, and had a pre-existing opinion for each company, thinking both were “dogs with fleas.” Bluestar was different. Gekko did not know the company, which became obvious when he said, “Rings a bell somewhere.” Then he dismissed the idea out of hand, indicating that it did not fit his criteria when he said, “Don’t like airlines; lousy unions.” However, when Fox mentions a favorable ruling on a lawsuit that “even the plaintiffs don’t know,” the hook was set and Gekko’s attention was captured.

Let’s dissect the situation with Bluestar a little further. Greed was the primary motivator when Gekko called later that afternoon to instruct Fox to “buy me twenty thousand shares of Bluestar. No more than 15 ⅛, ⅜ tops, and don’t screw it up, sport.” To Gekko, the return was very compelling. A “five-point pop” implied a potential return of more than 30% over a very short time horizon. Gekko’s greed overwhelmed any concern he had about the unions. The news was imminent, so Gekko felt that the downside was limited because a few days of market risk should not be a big factor. Gekko liked the idea because he knew he had an informational advantage. While highly illegal, he had information that had not been disseminated to the market, which resulted in a mispricing, as we show in Figure 11.1. Last, Fox had identified a catalyst—the soon-to-be-issued press release—that he knew would send the stock higher.

Figure 11.1 Lack of Dissemination Results in Mispriced Stock

When we run Fox’s Bluestar idea through the Steinhardt framework, we see that all the boxes are checked:

- Is your view different from the consensus? Yes. The consensus is neutral to negative concerning the outcome of the litigation.

- Are you right? Yes. Fox has material nonpublic information concerning the favorable outcome of the litigation.

- What is the market missing? The market does not know the outcome of the litigation.

- When and why will the consensus view change? The consensus view will change when the news of the positive outcome is released.

Ideally, your hook will contain all these factors, although we recognize there is an awful lot of information to squeeze into 30 seconds. If you were to pitch Cloverland, which we discuss in Chapter 8, to Gekko, it might sound like the Bluestar exchange, albeit without the illegal component:

- You:

- Cloverland Timber.

- Gekko:

- Rings a bell somewhere. So what?

- You:

- Owns 160,000 acres of timberland in Wisconsin. It is a microcap that trades on the Pink Sheets with a sleepy investor base and no one paying attention.

- Gekko:

- Don’t like microcaps; roach motels—you can get in, but can’t get out.

- You:

- Last year an activist—John Helve of Brownfield Capital—flew a satellite over the land and hired a consultant to do an appraisal. Brownfield bought 26% of the stock and got a board seat a few months ago. Market price is $90 a share, but it’s worth at least $140. The activist isn’t going to just stand by and watch the trees grow; they’ll push for a sale.

- Gekko:

- How do you know?

- You:

- I met John a few years ago at a dinner and we’ve since become friends. His fund, Brownfield, has a good track record. While he didn’t give me exact numbers, he said the trees are older, with a higher percentage of hardwood than the market has been told by the company, which means the timberland is a lot more valuable than investors realize. If the activist is successful, you could make 50% on your money in 18 months. Even if the activist isn’t successful, given that timber is a hard asset, there is little downside risk.

- Gekko:

- Interesting. You got a card? [then a long pause] I look at a hundred ideas a day. I choose one.

When we run the Cloverland opportunity through the Steinhardt framework, we see that all the boxes are checked:

- Is your view different from the consensus? Yes. The consensus thinks the stock is worth $107 per share; you think it’s worth $140.

- Are you right? Yes. You know your valuation is accurate based on the satellite appraisal of the value of the timberland.

- What is the market missing? The market does not know the true value of the timberland. Also, the market appears to be unaware of the activist or does not think he will be successful.

- When and why will the situation change? The situation will change when the activist persuades the board to put the company up for sale.

As we identified in Fox’s pitch of Bluestar, Gekko’s first reaction to the Cloverland pitch was greed. Gekko saw an opportunity to make money. Most portfolio managers are motivated by greed and the opportunity will capture their attention if the implied return is compelling. However, fear often kicks in at the point the manager’s thinking shifts from “How much can I make?” to “How much can I lose?”

A manager’s fear is measured by his perception of uncertainty, which includes both the uncertainty of the investment outcome and his uncertainty in your analytical abilities. The manager’s fear will be mitigated if he believes the downside is limited and if he has confidence in your analytical prowess.

If there is sufficient return and low perceived risk, most seasoned portfolio managers will then ask the question, “Why me o’lord?” reflecting their concern that the opportunity looks too good to be true. This only half-rhetorical question is the third potential hurdle you must overcome to convince the manager to adopt the idea. To neutralize this objection, you must demonstrate that a genuine mispricing exists by proving that at least one of the market efficiency tenets has been compromised, as we discuss in Chapter 5.

Once this worry is put to rest, the portfolio manager will most likely raise one final concern: “How will the consensus realize the mispricing exists and, in turn, correct it?” In other words, “What will be the catalyst that closes the gap between the market price and intrinsic value?” Seth Hamot, a well-respected hedge fund manager, posed this question a bit more colorfully by saying, “Now that I have gone through all this brain damage, untangled this rat’s nest of a situation and figured it out, how is the next guy going to figure out how to untie the knot so I can make some money?”5

We recap the portfolio manager’s list of potential concerns in Figure 11.2 and show how the analyst can deliver the perfect pitch by anticipating what the manager will think and using the Steinhardt framework to structure his presentation.

Figure 11.2 Questions to Achieve the Perfect Pitch

We show that the analyst successfully economized his time with no wasted words when we dissect the Cloverland pitch and parse the statements that were made into the different categories listed in Figure 11.2. The review illustrates that the pitch made four specific arguments to address the portfolio manager’s four primary questions, which are as follows:

- The intrinsic value is $140 per share.

- The activist will be successful.

- The thesis is not priced into the stock.

- There is little downside even if the activist is unsuccessful.

We list the different phrases from the hook and place them in the appropriate category in Figure 11.3. By using the Steinhardt framework as a guide, the chart shows that the analyst answered the portfolio manager’s basic concerns in a concise fashion, which resulted in the perfect pitch.

Figure 11.3 The Perfect Pitch for Cloverland

After listening to literally thousands of stock pitches, we firmly believe that the most common mistake most inexperienced and experienced analysts make is presenting arguments without fully understanding how they arrived at their conclusion. This shortcoming results in a weak pitch that is hard to defend and quickly crumbles when challenged. To be successful, you need to answer the why questions. Why do you believe the intrinsic value is $140 per share? Why will the activist be successful? Why isn’t the investment thesis priced into the stock? Why is there little downside to the stock?

Even if you address the portfolio manager’s four main concerns with four strong arguments, you cannot stop there. You need to have complete command of the evidence that supports your arguments, including the assumptions you are making. You will also need to anticipate and prepare for any possible counterarguments.

Constructing a Formidable Argument Using the Toulmin Model

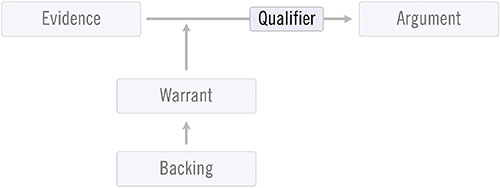

It is critically important to instill a mental discipline when developing arguments so that you understand what information you need to defend them. To accomplish this goal, you will need some type of systematic framework or checklist with which to scrutinize your arguments. You need someone to look over your shoulder, asking tough questions as you craft your pitch, and acting as your conscience, picking apart your argument and second-guessing all your assumptions. That someone is Stephen Toulmin and the systematic framework is the Toulmin model of argumentation.

Stephen Toulmin, a British philosopher, focused his research on moral reasoning. In his seminal work, The Uses of Argument, published in 1958, Toulmin outlined six interconnected components for analyzing an argument, referred to as the Toulmin model of argumentation. The Toulmin model can be used to structure and “stress test” the arguments in your pitch, and in the process produce arguments that are more reliable, credible, efficient, and less susceptible to counterarguments. The result will be a much more effective pitch.

The Argument

One of the arguments you made in the Cloverland pitch was “The activist will be successful in forcing a sale of the company.” An argument is a statement you want to convince your audience is true. During the pitch, your statement will likely be challenged by a simple question such as the one Gekko might ask, “How do you know?” When responding, you must have adequate evidence to support your argument.

For instance, you might present the following evidence to prove that John Helve will be successful in forcing a sale of the company in the Cloverland example:

- Brownfield was successful in their last activist campaign.

- Cloverland stock has underperformed the S&P 500.

- Brownfield has a significant position in Cloverland.

- Brownfield has received one board seat and John Helve is already a board member.

The Evidence

Evidence, often called data points, usually includes facts, statistics, personal observations or expertise, physical proof, expert opinions, or reports and will have different levels of quality across several dimensions, as outlined in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4 The Dimensions of Evidence Quality

The more convincing the evidence, the stronger the argument, which should be obvious. The characteristics listed in Figure 11.4 provide an important guideline as to the relevance of your evidence and can provide a measure of its quality.

For example, one of the data points in the argument “Helve will be successful” was that “Brownfield was successful in their last activist campaign.” We can screen that piece of evidence through the five characteristics to determine how good it is:

| Relevance: | Whether they were successful in their last campaign is relevant to their success with this campaign. |

| Accuracy: | Depending on how you define successful, the data is verifiable, so its accuracy can be determined. |

| Adequacy: | Taken alone, this piece of evidence is not sufficient to prove that they will be successful with this particular campaign. |

| Credibility: | The data comes from a reliable source. |

| Representative: | The data might not be representative since the last campaign had a completely different set of circumstances. |

We might conclude that taken alone, the data point is not sufficient to prove the argument that Helve and Brownfield will be successful with Cloverland. However, this statement is only one of four data points we are using to prove the argument and, when added to the other three data points, will make the argument much stronger—which is why it is advisable to have more than one data point supporting your argument.

The Warrant

Questions about evidence are not the only way your audience may challenge your arguments. They might ask you, “How did you arrive at this conclusion?” or “Why do you think that?” These questions are not intended to challenge the validity of the evidence; rather, they ask how you made the leap from the evidence to the argument. Supplying further facts will not answer this question. Instead, you will need to demonstrate that the argument follows from the evidence in a logical manner. Toulmin calls this bridge a warrant, which answers the question, “Why does that evidence mean your argument is true?”

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects individuals against unreasonable searches and seizures. Only if there is probable cause will a judge issue a search warrant. Imagine there is a jewel heist. Police have collected fingerprint evidence from the crime scene that points to Julie Zlato as the perpetrator. The police suspect Ms. Zlato is hiding the jewels in her home, but they cannot just barge in and rummage around her house looking for the jewels. To enter her house, the police need a search warrant. However, they will need to establish probable cause with the judge, linking the evidence to the accusation, for the judge to grant the warrant.

Toulmin’s warrant is conceptually similar to a search warrant as there needs to be a logical connection between the evidence (the fingerprints at the crime scene) and the argument (Zlato is the perpetrator), which is similar to probable cause in the robbery. Toulmin’s warrant answers the question, “How did you arrive at this conclusion?”

If we put the Cloverland argument through the Toulmin framework, we see that the warrant has four facets:

- Helve was successful in his last activist campaign, so he will be successful in this campaign.

- Since the stock has underperformed the S&P 500, the shareholder base is disgruntled and will likely vote with Brownfield if they launch a proxy fight.

- Brownfield has amassed a large position in Cloverland and has significant leverage with the board.

- Helve is already on the board, so he can better influence management.

The portfolio manager can challenge the warrants by making statements such as, “Just because Brownfield was successful in its last campaign does not mean they will be successful in this one” or “Just because the stock has underperformed the S&P 500 does not mean that Brownfield will get shareholder support.” The portfolio manager uses these questions to challenge the warrant, which is the cause-and-effect relationship between the evidence and the argument.

We firmly believe that most pitches fail because the analyst takes the warrant for granted. While it may not be necessary to state explicitly a warrant when making an argument, it is critical to understand the link between the evidence and the argument, and to be prepared to defend the warrant if it is challenged.

The Backing for the Warrant

You will need what Toulmin calls backing to defend or support your warrant.

The backing supports the warrant by outlining the reasons why the warrant is valid. It is the evidence that supports the warrant. For example, if you were defending the warrant “Since the stock has underperformed the S&P 500, the shareholder base is disgruntled and will likely vote with Brownfield if they launch a proxy fight,” the backing might be that something like:

- You spoke with investors representing 30% of the shareholder base and they said that they would likely vote for Brownfield in the event of a proxy fight; or,

- Brownfield has won 75% of its proxy fights in situations where the target company’s stock underperformed the S&P 500 for the previous five years.

The Qualifier

It’s important to keep in mind that no argument is foolproof. The world is uncertain and unexpected events can and will happen. For instance, Cloverland’s directors could vote to increase the size of the board (diluting Brownfield’s influence) or the forest might become infested with mountain pine beetles, which has the potential to kill a large percentage of Cloverland’s trees and reduce the company’s estimated intrinsic value. To account for these uncertain events, a qualifier acknowledges the limitations of the argument and indicates the level of confidence in the argument by using words such as unlikely, possibly, likely, and probably.

A qualifier in the Cloverland situation might be, “Helve will probably be successful, although there is a possibility that Cloverland could expand the size of its board.” Or, “Brownfield’s large position will probably give them sufficient leverage to be successful, although it is possible that the board will dig in their heels and drag out the process.”

The Rebuttal and Counterarguments

The last element of the Toulmin model is the rebuttal, which addresses potential counterarguments.

Cicero states in his book De Inventione, I,

“Every argument is refuted in one of these ways: either one or more of its assumptions are not granted, or if the assumptions are granted it is denied that a conclusion follows from them, or the form of argument is shown to be fallacious, or a strong argument is met by one equally strong or stronger.”6

The Toulmin model mirrors Cicero’s observation. For instance, a counterargument to the Cloverland example might be, “While Brownfield owns a lot of Cloverland stock, it is not a large position for their fund; therefore, they may not be aggressive in the situation if their attention gets diverted.” The rebuttal acknowledges limitations or exceptions to the argument and mitigates the counterargument. It acknowledges situations where the argument might not hold, such as, “The position for Brownfield is not a large one. They might not focus on Cloverland if they find another situation that diverts their attention. However, they most likely will not lose focus because they don’t want their reputation tarnished.”

The Stress-Tested Argument

Although using the Toulmin model may seem like overkill for an investment recommendation, it is an excellent tool for stress-testing your pitch and making sure your argument can withstand attack. The model provides you with an X-ray view inside your argument to see its entire anatomy and identify areas where the argument might be vulnerable, before being grilled by an intimidating portfolio manager.

If we decided to redo the Cloverland pitch we gave Gekko’s office, the hook might sound like the following:

Based on a rigorous analysis of a wide range of information that I will discuss later, I have concluded that John Helve’s firm, Brownfield Capital, will be successful in forcing a sale of Cloverland Timber, which would then close in 9 to 12 months. The stock, which is currently trading at $90, is worth $140, a 56% potential return. Given the sleepy nature of the shareholder base and the stock’s limited trading liquidity the stock appears to be mispriced as the market is not properly incorporating the true value of the timber or the actions of the activist investor into the stock price. Even if the activist is not successful, there is little downside because timber is a hard asset.

With this hook, you have covered the four main elements of your investment thesis and address the four key questions the portfolio manager will have:

- How much can I make? The stock is worth $140 per share.

- How will the next guy figure it out? The activist will be successful.

- Is it too good to be true? The thesis is not priced into the stock.

- How much can I lose? Even if the activist is not successful, there is little downside.

If the portfolio manager is intrigued by your hook, he then will allow you to proceed to your two-minute drill. Ideally, you will use the two-minute drill to delve further into the evidence to support the arguments from your hook. If we use the Toulmin model as a framework to develop the two-minute drill, the portion of the presentation discussing the valuation might be similar to the following:

I believe that Cloverland stock is worth $140 per share, implying a value of $1,130 per acre. My valuation is based on the results of a survey performed by consultants hired by Helve’s firm that specialize in appraising timberland. The consultants flew a satellite over the forest to take photographs and then, using sophisticated computer modeling, estimated the value per acre based on density, age, and species of the trees. While the average age to harvest a tree is 40 years, the trees on Cloverland’s property are closer to 70 years old. Older trees are much more valuable because of their greater volume of wood. The survey also showed a high percent of sugar maple, which is a hard wood and much more valuable than soft wood. Sugar maple is also more resistant to the mountain beetle, which should help prevent any unforeseen damage from an unexpected infestation. While valuation based on appraisals from satellite flyovers is a new technology, and like any valuation method is prone to error, this type of analysis has proven over time to be more accurate than traditional valuation methods from on-the-ground surveys.

If we dissect one portion of the two-minute drill, we see that the analyst has included all the points from the Toulmin model:

| Argument: | “I believe that Cloverland stock is worth $140 per share, implying a value of $1,130 per acre.” |

| Qualifier: | “While valuation based on appraisals from satellite flyovers is a new technology, and like any valuation method is prone to error.” |

| Evidence: | “My valuation is based on the results of a survey performed by a consulting firm hired by the activist that specializes in appraising timberland.” |

| Warrant: | “The consultants flew a satellite over the forest to take photographs and then, using sophisticated computer modeling, estimated the value per acre based on density, age, and species of the trees.” |

| Backing: | “While the average age to harvest a tree is 40 years, the trees on Cloverland’s property are closer to 70 years old. Older trees are much more valuable because of their greater volume of wood. The survey also showed a high percent of sugar maple, which is a hard wood and much more valuable than soft wood. Sugar maple is also more resistant to the mountain beetle.” |

| Rebuttal: | “This type of analysis has proven over time to be more accurate than traditional valuation methods from on-the-ground surveys.” |

The argument must consider the counterarguments that the portfolio manager is likely to make and you must be prepared to confront them head-on. To quote Aristotle, “In deliberative oratory . . . one must begin by giving one’s own proofs and then meet those of the opposition by dissolving them and tearing them up before they are made.”7 For instance, an obvious counterargument might question the validity of a valuation method based on satellite photography, which is addressed in the rebuttal.

If the portfolio manager remains interested in the idea after your two-minute drill, you will likely get follow-up questions, which you need to anticipate in advance and be prepared to address. You are expected to know more about your argument than anyone else and need to be an expert on the facts. For instance, questions the manager might ask regarding the valuation portion of your argument are:

- How accurate has this method of valuation been over time? Is the estimated value usually understated or overstated? How can the consultants tell the age and species of a tree from satellite photos? Have their results been accurate in the past?

- Tell me more about the background of the consultants. How long have they been in business? What is their reputation? Do they have a blue-chip client base?

- How much more valuable is sugar maple than typical softwoods? How much of the increased valuation is based on this factor?

- Can any additional value be realized from mineral rights or real estate development?

Paul S. always said in his class, “If you don’t know the answer to the question the portfolio manager asks, what is the correct response?” He would then pause to see if any of the students would respond. No one ever did. Then he continued, “The right answer is, I don’t know but I’ll find out. And then you write down the question. You are not writing it down so that you remember it, you are writing it down so the portfolio manager sees you writing it down. Don’t try to fake your way through the answer. An experienced portfolio manager will sense BS like a shark senses blood in the water and you will not survive.”

Once you finish the process of properly organizing the content, you will have what amounts to a script or words on paper. However, the message has two components: the content and the delivery of that content. You now have the content, but the delivery matters too, as we show in the next chapter.

Gems:

- When determining which elements to include in your pitch, imagine that your house is on fire and you have only 30 seconds to evacuate. What three items would you take? Similarly, you need to think what are the three most important points to include in your pitch.

- The pitch should be structured into a 30-second hook, two-minute drill, and Q&A. The analyst uses the hook to tantalize the portfolio manager with the idea and motivate him to listen to the two-minute drill, which the analyst can use to present the crux of his pitch. The two-minute drill tells a story, lays out the main arguments to the pitch and reinforces the attractiveness of the investment. The goal of the two-minute drill is to draw the manager further into the idea and show that it has merit. If the analyst passes the two-minute drill, he can expect to get a deluge of questions from the portfolio manager.

- To deliver the perfect pitch, the analyst must address the four questions in the portfolio manager’s mind, anticipate what the manager will think, and use the Steinhardt framework to structure his presentation.

- We firmly believe that most pitches fail because the analyst takes the warrants to his arguments for granted. While it may not be necessary to state a warrant when making an argument, it is critical to understand the link between the evidence and the argument, even if it is unspoken, and be prepared to defend the warrant if the argument is challenged.

- Word choice is extremely important. Try not to use phrases that convey little information and avoid using weasel words in your presentation.