Organizing for Service Operations

ITIL describes four main functions that are responsible for carrying out all the lifecycle processes. These are the technical management, application management, operations management functions, and the service desk. The IT operations management function is further divided into IT operations control and facilities management. We will cover each of these in turn and then look at where the responsibilities of each function overlap. It is important to remember that ITIL is not prescriptive and does not specify an organizational structure or names of teams. The responsibilities of the functions described here should be carried out, but each organization will have its own structure.

Technical Management

Whatever the name given to the team or teams in any particular organization (infrastructure support, technical support, network management, and so on), the function referred to in the ITIL framework as technical management is required to manage and develop the IT infrastructure. This function covers the groups or teams that together have the technical expertise and knowledge to ensure that the infrastructure works effectively in support of the services required by the business.

Role

The technical management function has a number of responsibilities:

- It is responsible for managing the IT infrastructure. This would include ensuring that the staff members performing this function have the necessary technical knowledge to design, test, manage, and improve IT services.

- Although we discuss this function under service operation, the function provides appropriately skilled staff members to support the entire lifecycle. Technical management staff members would be involved in drawing up the technical strategy and ensuring that the infrastructure can support the overall service strategy. Technical management staff members would also carry out the technical design of new or changed services and would be involved in planning and implementing their transition to the operational environment.

- Once the service is live, technical management provides technical support, resolving incidents, investigating problems, responding to alerts, and specifying any changes or updates required to have the service operate efficiently. Technical management staff members will identify service improvements and work with the CSI manager to design, test, and implement these improvements.

It is the responsibility of the manager or managers of this function to ensure the correct number of staff members, with the correct skills to carry out the required tasks. Specifying the numbers and skill levels required is discussed as part of strategy and detailed as part of service design (as discussed in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4). Transition tests that the staff members are able to support the service as designed, and CSI identifies any improvements or training requirements. The technical manager must decide whether to employ new staff members with the correct skills, to train existing staff members, or to use short-term contract resources to meet a particular requirement. Larger organizations may have a team of subject-matter experts that can be called upon when required by subsidiary departments, without the need for those skills to be developed across the organization.

Most of the everyday operational support activities will be undertaken by the operations support staff members, but it is the responsibility of technical management, as the experts in the technology, to guide and support the operations staff members.

Objectives

The objectives of technical management include the following:

- Providing the appropriate technical infrastructure to support the business processes. This should take account of the availability and capacity requirements, providing a stable resilient infrastructure at an affordable cost.

- Planning and designing the technical aspects of any new or changed service.

- Implementing these technical aspects and supporting them in the live environment, using the technical expertise that the function possesses to ensure that any issues that arise are swiftly resolved.

Applications Management

The second service operation function described in the ITIL framework is that of application management. This function shares many features with the technical management function, although in this case it is the application software that is supported and managed throughout its lifecycle, rather than the infrastructure. Application management and applications development are not the same, and it is important to understand the differences between them:

- Application management is involved in every stage of the service lifecycle, from ascertaining the requirements through design and transition and then operation and improvement.

- Application development is mostly involved in single, finite activities, such as designing and building a new service. We discuss this in more detail later in this chapter.

As with technical management, the application management function may not be called this in many organizations. Whichever group of staff members is responsible for managing and supporting operational software applications is the application management function. As with technical management, this function may be split across a number of teams.

Application management may carry out some tasks as part of application development projects, such as design or testing. This is not the same as the work of application development itself.

Role

The application management function is involved in all applications. Even when the function has recommended purchase of the application from an external supplier, there is still a requirement for management activities to take place. These activities are very similar to those of the technical management function:

- It is responsible for managing the IT applications. This would include ensuring that the staff members performing this function have the necessary technical knowledge to design, test, manage, and improve IT services.

- It is the custodian of technical knowledge and expertise related to managing applications.

- Although we discuss this function under service operation, the function provides appropriately skilled staff members to support the entire lifecycle. Application management staff members would be involved in drawing up the application strategy. They would carry out the design of new or changed applications and would be involved in planning and implementing their transition to the operational environment. Once the service is live, application management provides support, resolving incidents, investigating problems, and specifying changes or updates required to have the service operate efficiently. Application management staff members will identify service improvements and work with the CSI manager to design, test, and implement them.

Application management staffing and training responsibilities are the same as those identified for technical management, and the function similarly interacts with the other stages of the lifecycle.

Application management also performs other specific roles:

- Application support ensures that the operations management staff members are given the correct training to enable the applications to be run efficiently.

- As part of service design, application management may carry out a training needs analysis covering the service operation staff members and provide the required training, but this role is a continuous one, providing day-to-day support to the operations staff members.

Objectives

The objectives of application management are to do the following:

- Identify functional and manageability requirements for application software

- Help in the design of applications

- Assist in their deployment

- Support the applications in the live environment

- Identify and implement improvements

To be successful, application management must ensure that applications are well-designed, taking account of both the utility and warranty aspects of service design. They must be able to deliver the right functionality at a reasonable cost, if the business benefit is to be realized. The provision of the correct numbers of appropriately skilled staff members is essential so that these skills may be applied to resolve any application failures.

Application Development vs. Application Management

As discussed earlier, application management and application development have separate aims and responsibilities. These two groups may work closely together or may be quite separate, with different reporting structures and a different interface with the business. Application development, as we said earlier, is normally a finite activity to develop an application, moving on to the next requirement when finished. Application management, on the other hand, remains involved throughout the lifecycle of the application.

- Development focuses on the utility aspects, and most of its work is carried out on applications developed in-house. Management activities consider both warranty and utility and are carried out whether the application is internally developed or purchased.

- Development is concerned with functionality and does not consider how it is to be operated or managed, whereas application management is concerned with how this functionality is to be delivered consistently.

- Development is often carried out as part of a project, with defined deliverables, costs, and handoff dates. This differs from application management, whose activities are ongoing throughout the service lifecycle and whose costs may not be separately identified.

- Developers may not have an understanding of what is required to manage and operate an application because they do not support the applications they have developed, instead moving on to the next development project. Similarly, application management staff members may have little involvement in development, meaning that they have a reduced understanding of how applications are developed.

- Development staff members work to software development lifecycles. Application management staff members are often involved only in the operation and improvement stages of the service lifecycle.

Figure 10.2 shows the differing roles of the application management and application development teams; the application development team is primarily concerned with the functionality of the application, whereas the application management team considers how the application infrastructure will support the application and how it will be built, deployed, and monitored in operation.

FIGURE 10.2 Role of teams in the application management lifecycle

Based on Cabinet Office ITIL® material. Reproduced under license from the Cabinet Office.

There is a growing tendency to end the division between the two teams, because it is confusing for the business to understand. Ideally, this will mean a broadening of the development role to include considering how applications will operate, and it will mean more involvement in development for staff members who will be managing the application.

Operations Management

The role of operations management is to carry out all the day-to-day activities that are required to deliver the services provided. The applications and technical management functions are the subject-matter experts in their respective fields and define what operational activities are to take place; operations management’s role is to make sure these are done.

The service design stage defined the required service levels, and the transition phase carried out tests to ensure that these were achievable; operations management is responsible for ensuring that these service levels are met consistently. Although the primary focus is on stability and availability, operations management will seek to continually improve by implementing changes that will help protect the live service or by reducing costs and opportunities for human error by implementing automation of routine tasks.

The quality of the service delivered to the business is dependent on operations management. This role is divided into two parts, covered next.

IT Operations Control

This part of operations management oversees the IT infrastructure. In larger organizations, this may be carried out as part of an operations bridge or Network Operations Center (NOC). In these organizations, there are dedicated staff members monitoring operational events on consoles and reacting to them as necessary, often in a separate area from the rest of IT. In smaller organizations, the line between technical management and operations control may be more blurred, with operations control being carried out by the technical management team, monitoring the systems from their desks, perhaps with one or two wall-mounted plasma screens. Whichever arrangement is chosen depends upon what suits the organization, but it is important that there are clearly defined expectations to ensure that the operations control tasks are carried out to the level required.

The operations control tasks include the following:

- The centralized monitoring and management of system events, as discussed, sometimes referred to as console management.

- The scheduling and management of batch jobs to carry out routine tasks, such as database updates.

- Carrying out backups of data and ensuring that this data can be restored if and when required. This may include the backup of entire systems or the restoration of individual files that a user may have corrupted.

- Although most printing is now carried out directly by the users, there may be certain requirements for centralized printing; pay slips will need to be printed in a secure environment to ensure confidentiality, and large print volumes may make centralized printing more efficient. The printing and distribution of these or other electronic output is an operations control task.

- Operations control will also undertake maintenance activities, under the guidance of the technical or application management functions; this could include archiving data, applying system packs, updating virus signatures, and so on.

Facilities Management

The other part of operations management is facilities management. Staff members involved in this will be responsible for the physical IT environment. This would include the following:

- Ensuring the necessary power is supplied (including any requirements for its quality, such as the prevention of any power spikes).

- Operating and maintaining any uninterruptible power supply (UPS) and generators. Facilities management is responsible for ensuring that these are available and for testing to ensure that they will work as designed, in the event of a power failure. This role may cover just a server room in a smaller organization or one or more data centers for larger ones.

- Ensuring the power provided at any disaster recovery sites has the required protection from failure and ensuring the maintenance of satisfactory air conditioning/cooling for rooms housing IT equipment, whether this is a server room or a complete data center.

Many organizations have undertaken data center or server consolidation projects in recent years to take advantage of technical advances. The facilities management function would be responsible for managing any such projects. In the case where the data center management is carried out by a third party, it would be the responsibility of facilities management to ensure that the external service provider was carrying out the required tasks to the agreed standard and managing any exceptions utilizing the supplier management process.

To be effective, operations management needs to understand the technology and how it supports the services provided, although this level of knowledge will be less than that provided by the technical and application management functions. There is a risk that operations staff members do not interact with the business as part of their work and so may fail to appreciate the business impact of failures or to understand the business importance of services, thinking of them in purely technical terms. It is essential that they have adequate understanding of the business aspect; the information showing how technology supports the business is available in the CMS, but specific training may be required to ensure that they have the necessary appreciation of the impact technology has on the business.

The importance of stability of services has been already mentioned; one way of maintaining that stability is to ensure that routine tasks are carried out consistently, no matter which staff members are on shift. This requires that properly documented procedures and technical manuals are available to operations staff members.

The performance of the operations management function should be measured against clear objectives, based on the performance of the service, not merely of the technology. Delivering the service to the required level, within the agreed cost, is essential, so operations management should be able to demonstrate the effectiveness of what they do but also prove that they are operating at maximum efficiency. Operations management should always strive to optimize the use of existing technology and exploit new technical advances to provide the required level of service at the best cost.

Objectives

The objectives of IT operations management include continuing to provide stable services to enable the business to obtain the business benefits from the service, while also investigating possible improvements to enable the service to be provided more cost-effectively.

Service operation’s other objective is to overcome any failures that do occur as quickly as possible in order to minimize the impact to the business.

Overlapping Responsibilities Between Functions

The responsibilities for managing many aspects of the operational environment are often shared, with the technical management and application management teams providing specialist support for each area, while operations management carries out the monitoring and maintenance activities and dealing with the simpler faults. Figure 10.3 shows this overlap; under the headings of technical management and application management there are examples of areas of responsibility such as networks and specialist applications, with the figure showing how the responsibility for these is shared with service operations. The figure also shows those activities that are entirely service operations’ responsibility, such as backups. The service desk is shown for completeness, but its responsibilities and those of the other functions do not overlap.

FIGURE 10.3 Service operations functions

Based on Cabinet Office ITIL® material. Reproduced under license from the Cabinet Office.

The Service Desk Function

The final service operation function described by the ITIL framework is that of the service desk. A service desk is a functional unit consisting of a dedicated number of staff members responsible for dealing with a variety of service activities, usually made via telephone calls, web interface, or automatically reported infrastructure events. We will cover this function in more detail, because it plays a critical role in customer satisfaction. Although the service desk staff members do not have the same level of in-depth technical knowledge as the staff members in the other functions, their role is just as important.

The service desk function is the most visible of the four functions; every hour of every day they come into contact with business users at all levels. A poor service desk can result in a poor overall impression of the IT department, while an efficient, customer-focused team can ensure customer satisfaction even when the service is operating below the agreed service level.

An essential feature of a service desk is that it provides a single point of contact (SPOC) for users needing assistance. It provides a single day-to-day interface with IT, whatever the user requirement. It provides a variety of services:

- Handles incidents, resolving as many as possible, where the resolution is straightforward and within the service desk authority level

- Owns incidents that are escalated to other support groups for resolution

- Reports problems to the problem management staff members

- Handles service requests (including ensuring that requests for software to be installed have the required license)

- Provides information to users

- Communicates with the business about major incidents, upcoming changes, and so on

- Manages requests for change on the user’s behalf if required

- Manages the performance of third-party maintenance providers, ensuring that they provide the agreed service

- Monitors incidents and service requests against the targets in the SLA and provides reporting from the service desk tool to show the level of service achieved

- Updates the CMS as required

- Gathers availability figures, based on incident data

Staffing

The service desk will use a service management tool and other technical resources to enable it to carry out its tasks and will follow defined processes (especially incident management and request fulfillment). Although these tools and processes are important, the people aspect of the service desk is critical. The interactions with the customers and users require good communication skills, in addition to technical knowledge. Knowing the answer is only part of the job; explaining it in terms that users understand is essential.

Recruiting and retaining good service desk staff members is the key to customer satisfaction. This function often acts as an entry level to the other functions, providing staff members with an understanding of all the services, the technology that supports them, and the business impact of failure. This provides an excellent basis for future technical specialization.

Service desk staff members require a mix of technical knowledge and interpersonal skills. The technical knowledge may not be in depth, but it covers all the services provided by the IT service provider. The service desk analyst can be said to know a little about a lot of services, rather than a lot about a few.

The ability to correctly prioritize incidents based on business impact and urgency (see the discussion of incident management in Chapter 11) requires that the service desk analyst has a good level of awareness about the business processes. Added to this knowledge is the requirement to be patient, helpful, assertive when dealing with support teams or third parties who are failing to meet targets, well-organized, and calm under pressure.

Service desks are organized differently dependent upon the particular requirements of the organization. We cover various service desk structures later in the chapter. The skill level required may also vary; the service desk may be tasked with resolving a high proportion (75 percent to 80 percent) of incidents, or it may be limited to logging and escalating them for resolution by another team. Service desks are often outsourced to specialist providers; the decision whether to do this will be based on the overall IT strategy. If the decision is made to outsource, the third-party supplier’s performance must be monitored and managed closely to ensure that this essential service is being provided to the highest standard.

Role

The provision of a single point of contact is accepted in many industries as being central to good customer service. Without a service desk, users would have to try to identify which IT support team they should approach. This could be confusing for the business, leading to a delay in having their issue resolved. Technical staff members would waste time dealing with issues outside their specialist area or issues that could be dealt with by more junior staff members.

Providing a good service desk leads to a number of benefits:

- Increased focus of customer service

- Increased customer satisfaction

- Easier provision of support through the single point of contact

- Faster resolution of incidents and fulfillment of requests at the service desk, without the need for further escalation

- Reduced business impact of failures because of faster resolution

- More effective use of specialist IT staff members

- Accurate data regarding the numbers and nature of incidents, taken from the service desk tool

Objective

As we have said already, the main objective of the service desk is to provide a single point of contact. The next most important objective is to restore service in the event of a failure. This may not mean a complete resolution of the incident, but the provision of a workaround, to enable the user to continue working. Fulfilling a request, resetting a password, or answering a “How do I ... ?” query all help the user get back to work as soon as possible.

Other responsibilities of the service desk include the following:

- Logging all incidents and requests, with the appropriate level of detail

- Categorizing incidents and requests for future analysis

- Agreeing on the correct priority with the user based on impact and urgency (utilizing SLAs wherever possible for consistency)

- Investigating, diagnosing, and resolving incidents whenever possible

- Deciding upon the correct support team to whom to escalate the incident should the service desk be unable to resolve it

- Communicating progress to the users

- Confirming closure of resolved incidents with the user

- Carrying out surveys to ascertain the level of customer satisfaction

We will cover some of these activities in more depth when we look at the incident and request processes.

Service Desk Organizational Structures

The best structure for the service desk is dependent upon the size and structure of the organization. A global organization will have different needs from one with all its employees based in the same location. Here we look at the most common structures; the best option may be a combination of them.

Local Service Desk

This option provides a service desk co-located with the users it serves; an organization with three offices would have three local service desks. There are advantages with this approach, in that the service desk is local, so it understands the local business priorities. Where the offices are spread across different countries, local service desks provide support in the language of the local users, work in the same time zone, have the same public holidays, and so on. This structure can also be useful when different locations have specialized support needs. The basic principle of a single point of contact is retained, because, from the user perspective, they have only one number to call and are unaware of any other desks that may exist.

This is an expensive option, because each new office location would require a new service desk too. At quiet times, there would be several service desk staff members spread across the various desks waiting for calls. There are potential issues with incidents and requests being logged in different languages, possibly in different systems; this makes incident analysis and problem identification difficult. Sharing knowledge is also more difficult: an incident that could be resolved by one service desk might be escalated by another, because the resolution has not been shared between the desks.

To overcome these issues, IT management must ensure that information is shared effectively. Procedures need to be put in place to ensure that issues affecting more than one location are managed effectively, without duplication of effort, or each service desk assuming that another desk is responsible. Figure 10.4 shows the local structure.

FIGURE 10.4 Local service desk structure

Based on Cabinet Office ITIL® material. Reproduced under license from the Cabinet Office.

Centralized Service Desk

A more common structure for service desks is that of a centralized service desk. In this model, all users contact the same service desk. This has the benefit of providing economies of scale, because there is no duplication of provision. Specialist technology, such as intelligent call distribution or an integrated service management tool, may be justified for a centralized service desk, but not when implementing this technology across many sites. There are no issues with confusion regarding ownership of major incidents, and knowledge-sharing becomes much more straightforward. Offering a service at times of low demand is more cost effective when only one service desk needs to be staffed.

Staff members on a centralized desk will gain more experience of particular incidents, which a local service desk may encounter only occasionally, leading to an increased ability to resolve these issues immediately. Where the centralized desk is supporting users in many countries, the language issue may be resolved by either of the following:

- Employing staff members with language skills and using technology to allocate calls requiring support in a particular language to staff members who have that language ability. Staff members would then log the call in the main language.

- Standardizing on one language; callers would need to report incidents in that language, and support would be provided in it. This option depends on the type of organization and whether its users may reasonably be expected to be able to converse in the language. Local superusers may be required to support users without the necessary language ability and to log calls on their behalf.

To provide support to a global organization, a 24/7 service may be required. Where the resolution requires a physical intervention (unjamming a printer, for example), the service desk would require local staff members to provide that support, answerable to the service desk.

Consideration should also be given to maintaining service continuity, because an event that affects a centralized service desk would impact support across the entire organization. A plan to provide the service from another location, possibly using different staff members, in the event of a disaster must be developed and tested, in conjunction with IT service continuity management. There should also be plans in place to ensure the service desk’s resilience in the event of disruption to the network or a power failure.

Figure 10.5 shows the centralized structure.

FIGURE 10.5 Centralized service desk structure

Based on Cabinet Office ITIL® material. Reproduced under license from the Cabinet Office.

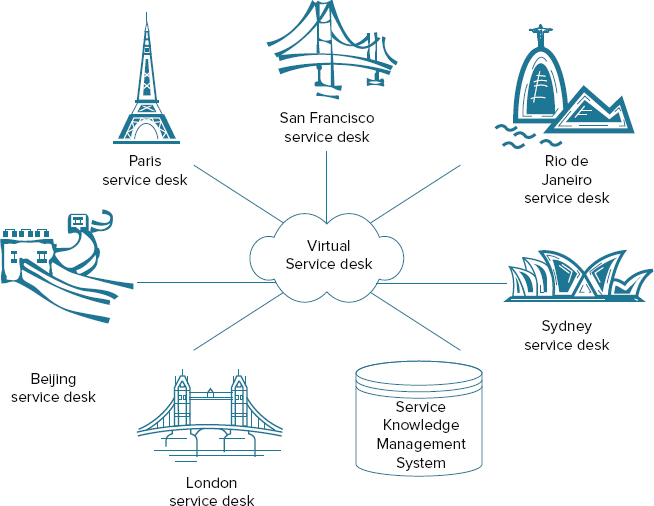

Virtual Service Desk

The third organizational option described by ITIL is that of a virtual service desk. This option consists of two or more service desk locations that operate as one desk. Calls and emails are distributed across the staff members as if they were in one centralized location. This ensures that the workload is balanced across all the desks. To the user, the virtual service desk appears as a single entity; the users may be completely unaware that this is not the case in reality. The virtual service desk retains the single point of contact principle.

The considerations we discussed earlier regarding knowledge sharing and clear ownership apply even more in this scenario, as does the need for all calls to be logged immediately. Users will become very frustrated if they call the service desk and explain an issue in detail, only to find when they call for a second time that the service desk analyst can find no record of their first call.

The ability to route calls to analysts with particular language knowledge or to adopt one language for all users can be considered, as with a centralized desk. Calls must be logged on one common system, using one language, because the next analyst to handle the incident may be in another location.

The virtual service desk structure allows for a variety of ways of working. Many call centers use home-based staff members, who log on to the service desk telephone system and are allocated calls. Extra staff members from other teams can supplement the core service desk staff members at busy times, without the users being aware. Many of us have had the experience of calling a local company, only to have the call answered offshore outside of normal hours or during bust times.

Offshoring support (providing support from another geographical location where staff members’ costs may be lower) can be cost-effective but requires careful management to ensure consistency of service. Managers need to be culturally sensitive, because users may become irritated by staff members behaving in a way in which they find unfamiliar.

One benefit of a virtual structure is that it has built-in resilience; should one location go offline because of a major disruption affecting that location, the service would continue with little or no impact.

Figure 10.6 shows the virtual service desk structure.

FIGURE 10.6 Virtual service desk structure

Based on Cabinet Office ITIL® material. Reproduced under license from the Cabinet Office.

Follow the Sun

The fourth structure described within ITIL is known as follow the sun. This is a form of virtual service desk, but with this structure, the allocation of calls across the various desks is based on time of day, rather than workload.

“Follow the sun” enables a global organization to provide support around the clock, without needing to employ staff members at night to work on the service desk. A number of service desks will each work standard office hours. The calls will be allocated to whichever desk or desks are open at that time. Typically, this might mean a European service desk will handle calls until the end of the European working day, when calls will then be allocated to a desk or desks in North America. When the working day in North America finishes, calls are directed at another desk or desks in the Asia-Pacific region, before being directed back to the European desk at the start of the next European working day.

This option is an attractive one for many global organizations, providing 24-hour coverage without the need for shift or on-call payments. The requirements for effective call logging, a centralized database, and a common language for data entry referred to earlier for the virtual structure apply equally here. Procedures for handoff between desks are also required to ensure that the desk that is taking over knows the status of any major incidents, and so on.

To the user, the single point of contact still applies; they have one number to call, no matter who answers it or where the service desk analyst may be located.

Specialized Service Desk Groups

Another possible variant on the previous structures is to provide specialist support for particular services. In this structure, a user may call the usual service desk number and then choose an option depending on the issue they have. Typically, the message would say, “Press 1 if the call is regarding system X, press 2 if it is regarding system Y, or hold for a service desk analyst if your call is in regard to anything else.”

Although this approach can be useful, especially where in-depth knowledge is required to resolve a call, it is not popular with users when it expands to numerous options to choose from, followed by another message saying “Thank you. You now have a further n options.”

There is a danger that the user does not always know what support they need and may choose the wrong option, leading to delay and frustration. For example, a printer that will not print may be because of a hardware fault, a network issue, an application malfunction, or a user error. The user will not know which option to choose.

This specialist support option works best for a small number of complex services that require a level of both business and technical knowledge beyond what can reasonably be expected of a service desk analyst. Another possible reason to use this option is when the service contains confidential data. In this situation, the organization may wish to limit access to a small number of specialist support staff.