p.316

COMPETING AND COMPLEMENTARY NARRATIVES IN THE EBOLA CRISIS

Morgan Getchel, Deborah Sellnow-Richmond, Chelsea Woods, Greg Williams, Erin Hester, Matthew Seeger, and Timothy Sellnow

The surprise, threat, and uncertainty of crises create a momentary void of understanding. For at least a moment, those observing the onset of a crisis are not fully able to comprehend the nature of the crisis—the cause, the extent of the impact, and what can be done immediately. This “communication vacuum and meaning deficit of a crisis create a discursive space that is filled by narratives, often multiple and conflicting” (Seeger & Sellnow, 2016, p. 8). Narratives, the stories we tell that both help us comprehend the crisis personally and explain its origin and impact to others, structure the reality surrounding the crisis. Naturally, those whose reputations are at stake create stories where they and the organizations they lead are portrayed in the most positive light that is reasonable, based on the context of the crisis. Other stakeholders and observers tell stories from their perspectives. Often, the stories of external observers portray the organizations at the center of the crisis with a competing and less favorable tone. Over time, these competing stories coalesce or converge in the eyes of the publics that observe them, leading to less competition and divergence. As more evidence is known, some competing stories are discredited and others are verified. If, however, the crisis under consideration is fraught with ongoing controversy, the narrative process becomes increasingly complex before it resolves into a dominant or broadly accepted narrative.

Health-related narratives are particularly prone to such ongoing controversy. Unlike crises where a specific, contained incident leads to momentary calamity that is quickly resolved, health crises such as epidemics and pandemics linger on, punctuated by volatile points where a disease passes borders or surpasses expectations in its mortality as treatment options falter. In a health setting, the crisis narratives can divide repeatedly and unexpectedly as consequences and perceptions of severity shift and intensify. Such was the case with the West Africa Ebola outbreak beginning in 2013. Previous Ebola outbreaks, though devastating and frightening, had been contained to rural areas relatively soon after the initial diagnosis. In 2013, however, the outbreak took root in highly populated areas and began to spread at unprecedented levels. As the disease spanned across borders and continents, the West Africa Ebola narrative evolved in a fractured and contentious manner for nearly a year. Thus, the West Africa Ebola narrative is an exemplar of health-related crises and their narrative complexity.

p.317

In this chapter, we begin with an overview of how the narrative space created by crises moves through divergence to convergence. We then further explain how lengthy crises with high levels of visibility and hazard continually expand the narrative space to allow for exceptional clash in the narratives that are generated to explain the situation. We then provide a description of the controversial narrative that wove through the West Africa Ebola crisis. We conclude with theoretical explanations of the narrative convergence process in complex health crises and offer practical explanations for responding to such protracted crisis narratives.

The Natural Cycle of Crisis Narratives

Narrative explanations are inherent to the evolutions of crises. Crises typically move through three stages: pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis (Ulmer, Sellnow, & Seeger, 2014). During pre-crisis, warning signs, subtle or obvious, are present. If these warning signs are missed, ignored, or reach beyond human control, crises occur. In the aftermath of the crisis, investigations occur, corrective actions are taken, and retrospective learning takes place. The crisis ends with a return to pre-crisis where risks are monitored and the lessons learned from the crisis are applied (Seeger & Sellnow, 2016). Similarly, the natural cycle of crisis narratives begins with the onset of the crisis, divergence gives way to the convergence process during the post-crisis discussion, and converges into consistent lessons learned and steps toward future resilience in the new pre-crisis stage. During the crisis stage, multiple narratives are generated to explain what is happening, why it is happening, and who is to blame. The quantity of narratives and the magnitude of their impact are intensified when the crisis period is long.

The fact that multiple narratives emerge in response to crises is essentially positive. By their nature, crises create shock and surprise. Thus, multiple interpretations are naturally and spontaneously created by individuals witnessing the crisis based on their distinct observational points. Stifling this interpretive process through attempts to force a single consistent narrative interpretation onto the crisis process would be, at best, inaccurate and, at worst, a violation of free speech. Perelman (1969) explains that such pluralism in interpretation is essential in the public discussion of any contestable issue. He explains that allowing multiple voices to be heard in the comprehension process “refrains from granting to any individual or group, no matter who they are, the exorbitant privilege of setting up a single criterion for what is valid and what is appropriate” (p. 71). Without narrative plurality, for example, an organization or agency could impose a narrative that overlooks its transgressions, assigns blame to innocent or irrelevant parties, and dodges the need for change. Narrative plurality ensures that multiple voices are heard so that all those impacted by the crisis are represented in the narrative discussion. Problematically, narrative plurality can be a means for manipulation. Hidden agendas can be introduced into competing narratives, seeking to discredit opponents or as a ploy to distract or divert the discussion from meaningful debate to hostile and unproductive prattle. Over time, however, attempts at distraction are often exposed in a maturing and converging narrative (Seeger & Sellnow, 2016).

p.318

Narrative Plurality as Divergence

Multiple narratives appearing early in the crisis often provide distinct and even competing views of crisis (Heath, 2004). These narratives seek to answer consistent questions focusing on intent, responsibility, and evidence (Ulmer & Sellnow, 2000). Questions of intent focus on pre-crisis activities. Simply put, the narrative seeks to answer the question of whether those with some power to prevent or contain the crisis have the best interest of their stakeholders in mind. For example, were warning signals intentionally ignored? If so, what was the potential benefit to those who ignored the warnings? Questions of responsibility ask who is to blame. Did the disease spread at a rate that, given existing knowledge and capacity, could not have been avoided? If so, efforts to assign responsibility are futile. If, however, the response to the disease outbreak included dimensions of incompetence, apathy, or greed, then assigning responsibility is a natural step in resolving the crisis. Finally, answering questions of intent and responsibility involve the constant discovery and interpretation of evidence. Simply locating and sharing evidence is unlikely to resolve narrative divergence. Instead, evidence typically has some ambiguity in how it can be interpreted. Thus, narrative divergence is likely to continue until some degree of consistency is reached on the meaning of the evidence surrounding the crisis.

Moving From Plurality to Convergence

Narrative convergence is based on consistent interpretations, either partial or complete, from multiple sources (Perleman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969; Sellnow, Ulmer, Seeger, & Littlefield, 2009). Those impacted by crises seek information based on intent, responsibility, and evidence from multiple sources. This confirmation of information among sources is a natural process, particularly when individuals are directly impacted by or keenly interested in the crisis (Anthony, Sellnow, & Millner, 2013). As time passes and more is known about the crisis, some diverging interpretations are widely discounted. Elements of other interpretations appear consistently among a variety of sources. Some degree of disagreement may continue, but agreement is often seen on many aspects of the crisis as the narrative evolves. Accordingly, convergence is distinct from dominance or congruence. Dominance is narrative consistency that is based on information deprivation or coercion. A single narrative is dominant because that is all that the storyteller knows or because telling an alternative story results in punishment or a lack of reward. Congruence, which is seldom achieved, exists when agreement is undisputed and the storytellers believe there is no other story to tell. Congruent narratives would likely be so superficial or obvious that they are of limited interest to storytellers.

p.319

Narratives achieve congruence incrementally. As convergence begins, previously divergent narratives begin to align on particular assumptions and characterizations. Observers and storytellers see partial agreement among the differing representations of the intent, responsibility, and evidence surrounding the crisis. Complete agreement is unlikely and, based on Perelman’s (1969) notion of plurality, undesirable. Converging narratives have enough consistency to achieve probability and fidelity among storytellers and their audiences (Fisher, 1987). Narratives satisfy the criteria of probability when audiences generally believe the narrative is an accurate representation of the crisis. Narrative fidelity is more precise, focusing on the details shared in the narrative. As Table 16.1 indicates, narratives are convergent in the pre-crisis stage, become divergent in the crisis stage, and begin to converge as probability and fidelity are agreed upon by audiences in the post-crisis stages. Plurality should be present in all three stages of the crisis cycle, being most pronounced in the crisis stage, narrowing in the post-crisis stage, and largely focused on dimensions of fidelity in the pre-crisis stage.

Table 16.1 Convergence in Crisis Narratives

p.320

The West Africa Ebola Narrative

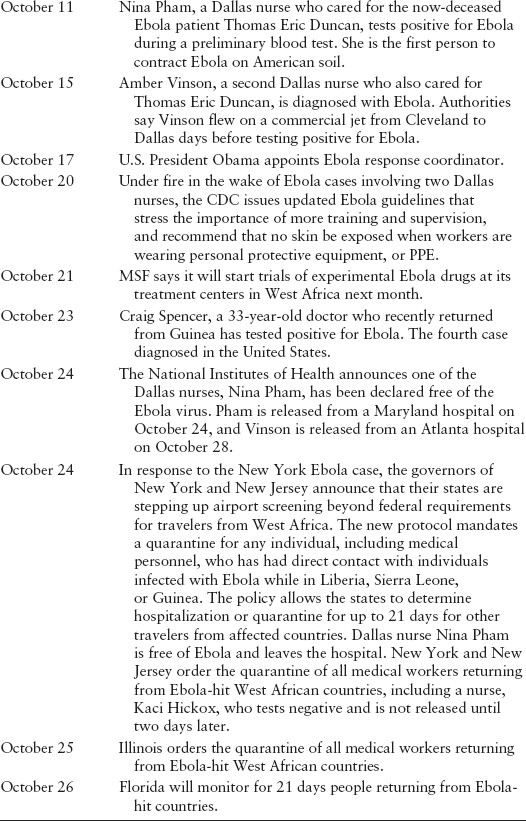

As mentioned above, prolonged crises, such as those created in response to health crises like epidemics, are slower in achieving narrative convergence. As the morbidity and mortality rise, crossing borders and continents, divergent narratives from multiple sources speculate about the peak of the disease and about the best ways to respond to it circulate (see Table 16.2).

Table 16.2 Ebola Outbreak Timeline March 2014 – November 2014

p.321

p.322

p.323

Compiled from CNN: http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/11/health/ebola-fast-facts/Reuters: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/10/28/health-ebola-idUSL2N0SG2FH20141028

p.324

Mapping the Ebola Narrative

Crises are surprising and uncertain events that require interpretation (Sellnow & Seeger, 2013). Meaning is created as more information becomes available and that information is shared in stories, most typically through news accounts, and increasingly through social media. Narratives from multiple sources help explain the threat and risk of the Ebola narrative. In this section, we explain how narrative explanations of the event differed based on many factors, ranging from who was speaking, their standpoint, who was being addressed, and how the risk was framed.

Initially, the Ebola virus became known to science in 1976, following an outbreak in Zaire. Ebola was identified as the source of severe viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) resulting in an intense albeit rapidly contained outbreak. Ebola is a member of the filoviridae family along with the Marburg virus, identified in German commercial laboratory workers in 1967. That outbreak was associated with African green monkeys imported for research (Peters & Peters, 1999).

Although sporadic outbreaks of Ebola have occurred in rural Africa, the disease has largely been a regional concern until the December 2013 outbreak in Guinea, which quickly spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone. Unlike previous outbreaks, the disease spread rapidly in urban centers. The lack of adequate medical infrastructure, cultural practices for burial, and a slow international response have been identified as factors related to the spread of the disease.

p.325

The 2014 Ebola Narrative

As the Ebola outbreak expanded in West Africa, it became the focus of media attention in the US. Two underlying questions framed US media coverage. First, questions were asked about how bad the outbreak was in Africa and what could be done to contain it. Second, questions were asked about the possibility of the disease coming to the US. This second question became particularly prominent after the death of Thomas Duncan in March.

Media coverage became much more prominent and included ongoing reports by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to address the heightened concern and interest in Ebola as well as commentaries and opinions from a variety of members of the medical community.

Public narratives about crises and risks tend, over time, to either converge or diverge (Seeger & Sellnow, 2016). Competing crisis narratives evolve toward unity as more information about the crisis is revealed. Technical information can provide understanding of how or why the crisis happened. First-hand accounts of loss and discomfort contribute to the narrative by humanizing the impact of the crisis. Emotional expression helps to reconcile divisions in preliminary and competing crisis narratives. As time goes on and more is known, evidence is validated or invalidated, the intent of those involved in the crisis begins to crystalize, and blame or responsibility is assigned. Through this process, narratives that were initially divided begin to homogenize as they move toward a common understanding of the crisis.

At their best, competing narratives create space for broader understanding and to test assumptions. The ensuing dialogue allows the expression of alternative views as well as functional understanding of the crisis and what steps could, should, or must be taken to manage the threat. At their worst, competing crisis narratives create space for manipulation, promote misunderstanding, and accelerate the harm. Competing narratives may interact with other issues or trends. Understanding the competing and converging narratives is central to understanding the larger narrative space of an event.

The Ebola Narratives

The goal of this project was to understand the public Ebola narrative(s) within the technical sphere and their relationship to one another. By technical sphere we mean those narratives offered by or referencing subject matter experts and grounded in scientific information about the disease, its treatment, risk, and development (Goodnight, 1999).

p.326

Narratives were tracked and coded as they were reported in the New York Times and the Washington Post beginning with September 30, 2014, the day the first US Ebola patient, Thomas Duncan, was diagnosed, and running through November. Those tracking the media were provided with a narrative mapping guide specifying the type of information to be gleaned from each article. Coders recorded the media outlet, date of publication, technical sources quoted, the narrative expressed by those sources, and if that narrative converged or diverged with the official narrative expressed by the CDC. An Excel spreadsheet was used to compile the data for further analysis. The specific narrative story line was recorded and the narratives were then assessed as convergent with the official narrative, divergent or both.

A wide variety of narrative sources were reported in the New York Times and The Washington Post. These included subject matter experts affiliated with government and universities, health care professionals, and organizations, including aid groups such as Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). Other narrative sources included business spokespersons, survivors, and politicians.

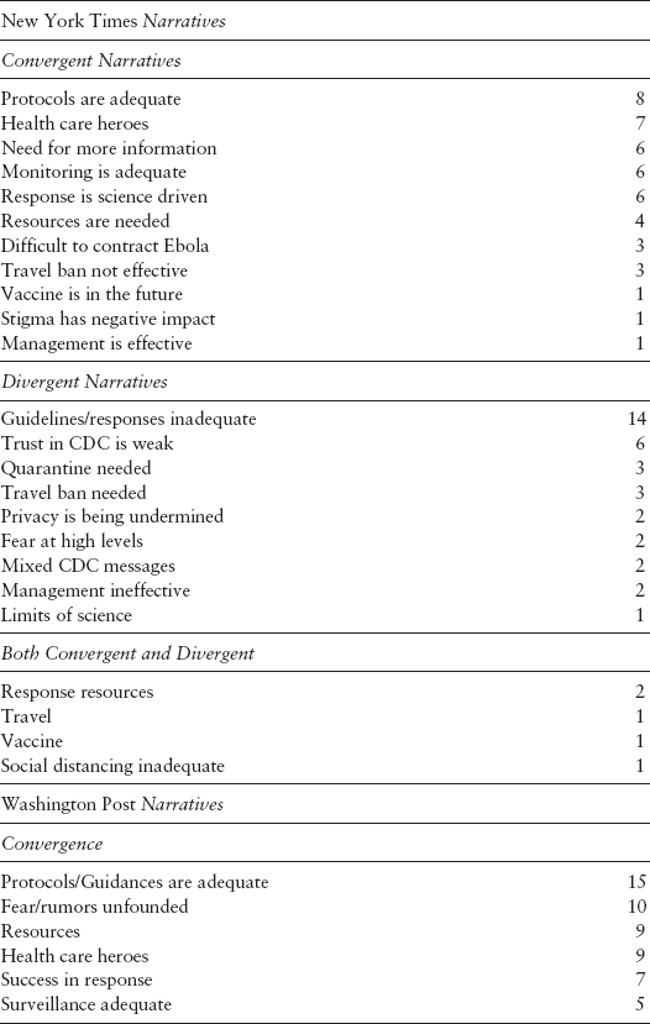

Of the 187 narratives reported in the NYT and WPO, 119 were convergent with the official narrative that Ebola represented a minimal threat (see Tables 16.3 and 16.4).

Official Narratives

The official narrative regarding the Ebola outbreak was offered by the CDC as the agency designated by federal law for leading infectious disease outbreaks. The CDC’s formal message and associated narrative was relatively consistent throughout the outbreak and focused primarily on the limited risk. These narratives came primarily from a science and public health perspective. According to this narrative, the risk to the average American of contracting Ebola was very small, in fact almost nonexistent. Because the disease can only be spread through direct contact with bodily fluids (urine, blood, saliva, feces) it is hard to contact Ebola through what would be considered casual contact. Moreover, people are not contagious unless they are showing symptoms of the disease (CDC, 2016).

In addition, the CDC noted that Ebola could be controlled in the US through established infectious disease management techniques and protocols. Travel bans, quarantines, and containment are not necessary and may be counterproductive by making any surveillance and reporting more difficult. Fear was unfounded and irrational. Established public health monitoring procedures are adequate. Finally, the Ebola outbreak was in West Africa, far removed from the US

Table 16.3 Ebola Narratives in the NYT and WPO

p.327

Table 16.4 New York Times and Washington Post Ebola Narratives

p.328

Supporting narratives include the science-based nature of the response, and claims that scientific support for protocols and guidance was adequate. A set of narratives about sufficient resources, robust surveillance, sound science, and success in responses complements the protocols and guidance are adequate narrative. Other converging narratives emerged that fears and rumors about Ebola were simply unfounded, that health care workers were heroes, and that stigmatization of people from Africa was dangerous and unfounded.

The official narrative was reiterated in public statements to officials including President Obama and Dr. Thomas Frieden, head of the CDC. On September 16, 2014, President Obama visited the CDC campus in Atlanta and gave a joint statement with Dr. Frieden. He emphasized the low risk:

First and foremost, I want the American people to know that our experts, here at the CDC and across our government, agree that the chances of an Ebola outbreak here in the United States are extremely low. We’ve been taking the necessary precautions, including working with countries in West Africa to increase screening at airports so that someone with the virus doesn’t get on a plane for the United States. In the unlikely event that someone with Ebola does reach our shores, we’ve taken new measures so that we’re prepared here at home.

p.329

(Obama, 2014, para. 4)

President Obama went on to praise the health care workers who were working to manage the threat in a professional manner.

This narrative that Ebola was not a threat and could be managed effectively was repeated in many media channels. Various accounts picked up the dominant Ebola narrative. This included a variety of subject matter experts (SME), surrogates, researchers, and public health officials. Exceptions to the dominant narrative by the SME community include a small number of researchers and some health workers, especially nurses.

The Divergent Narratives

Despite a dominant narrative supported by official sources, a counter and divergent narrative emerged. The dominant divergent narrative of the 2014 Ebola outbreak centered around statements by other subject matter experts including independent researchers and medical professionals. Political figures also expressed counter narratives based largely on a general distrust of the federal government as well as specific distrust of the Obama administration. In general, this counter narrative was grounded in three views.

First, the questions were raised about what was not known about Ebola. Most of these related to the possibility that Ebola could be transmitted without physical contact. Some suggestions were made that Ebola could be airborne through the aerosolized spread of mucus from sneezed droplets, although this route of transmission was considered very remote. Well-known epidemiologist Michael Osterholm published an opinion article on September 11, 2014, raising the possibility or airborne Ebola through viral mutations:

You can now get Ebola only through direct contact with bodily fluids. But viruses like Ebola are notoriously sloppy in replicating, meaning the virus entering one person may be genetically different from the virus entering the next [sic]. If certain mutations occurred, it would mean that just breathing would put one at risk of contracting Ebola.

(Osterholm, 2014, para. 5)

A second divergent narrative was grounded in claims that the CDC was simply wrong, or that the CDC was intentionally misleading the public or was simply incompetent. The Washington Post noted, for example, in an October 15, 2014, article that the CDC had been hedging its statements. The same article quoted a candidate for congress, Eric Williams, who openly asked, “Are we getting the truth?” The Post article pointed out that the chances of contracting Ebola in the US were exceedingly low, but went on to reference high levels of public concern.

p.330

Still, all over the country, Americans expressed deep anxiety about the threat of Ebola. According to a new Washington Post-ABC News poll, two-thirds of Americans were worried about an Ebola epidemic in the United States, and more than 4 in 10 were “very” or “somewhat worried” that they or a close family member might catch the virus (Harlan, 2014). Similar media reports quoted skeptical politicians, primarily Republicans, who suggested that the federal government was underreacting and that travel bans and quarantines were warranted (Barrett & Walsh, 2014). A number of commentators noted that the Ebola threat had become an influential issue for the midterm elections.

A third interpretation was based in a larger critique of science and included the limits of science, the uncertainty associated with emerging science, and the inadequacy of the government’s response. Specifically, the National Nurses United (NNU) was vocal in questioning the idea that medical protocols were sufficient. The NNU began to voice concern regarding a lack of preparedness following Duncan's diagnosis. What followed were public challenges to the CDC's recommendations. Following Dr. Frieden's statements about Nina Pham's protocol violation, the narrative shifted and become more critical of the CDC. The evolving narrative included claims that the CDC's original protocols were both insufficient and inconsistent for health care personnel treating Ebola patients.

Once the CDC introduced new guidelines, however, the NNU began to curb its criticism, stating that the CDC's revised actions were an improvement over previous recommendations, though not as strong as they should be to ensure adequate protection for health care workers. The NNU also acknowledged the CDC has no regulatory power and petitioned hospitals, the White House, and Congress to take action.

These narratives essentially critique and counter the CDC’s official narrative based on general distrust and fears. They primarily raised questions about the official, dominant narrative and suggested ways in which it was incomplete or did not fit the existing facts, such as the cases that had occurred in the US.

Discussion

The dominant narrative was predictable and familiar. Science can control the disease. Protocols are adequate. The risks are limited, almost nonexistent. This narrative was grounded largely in the credibility of the source—the Obama administration and the CDC. Overall, the divergent narrative emphasized the uncertainty and what remained unknown. Ebola is an exotic disease and the outbreak forced experts to deal with uncharted waters and numerous unknowns, including how the disease could spread. Overly broad assurances early on and changing guidelines—what protective gear to wear, how to wear it, how to dispose of waste, flight restrictions, and isolation measures—fueled the criticism of the CDC. Rather than being seen as responsive to concerns, they implied that the initial response was flawed. These changes in the response were portrayed as evidence that the CDC simply did not have all the answers.

p.331

Three additional factors supported the emergence of a divergent narrative. First, risk communication is always difficult with a novel threat where the science is emerging. Because the public did not understand Ebola, there was more room for diverse interpretations and explanations. Modes of transmission were not familiar. As the risks became manifest in ways that were not seen as consistent with the dominant narrative, the uncertainty became an increasingly central theme in the divergent narrative. Mistrust of the CDC came from skepticism about science and a view that expert opinion is elitist and condescending. Second, the journalistic norm of balance in news reports gave the counter narrative more substance than it might otherwise have warranted. Journalistic accounts often turn to alternative views as a way of telling both or multiple sides of the story and achieving objectivity in reporting. Fairness is sometimes achieved by covering multiple sides of any new story. Balance in a journalistic account can also add context and perspective. In some cases, the search for balance can support alternative storylines and competing narratives that otherwise would not have received attention. Balance may even encourage the development of those narratives by creating an outlet. Finally, as with all risks, the threat of Ebola had significant political implications. In this case, Ebola created an opportunity for the opposition to critique the Obama administration’s competence. Issues that create questions about public safety and security can be powerful political forces. The Ebola outbreak, occurring within a context so close to the election, enhanced the likelihood that the issue would be politicized.

This analysis provides several practical applications for risk and crisis communicators facing health-related crises. First, the uncertainty in health-related crises is unavoidable. Even the best science available leaves room for speculation regarding the potential for viruses to mutate, for treatments to fail in some individuals, and the potential for diseases to spread despite actions such as vaccination, protective protocols, and quarantines. Spokespersons should acknowledge this inherent uncertainty and take care to avoid over-reassuring the public. Indeed, acknowledging uncertainty is a tenet of effective crisis communication (Seeger, 2006). Had President Obama and Dr. Frieden been less definitive in their establishment of the primary narrative, they would likely have faced considerably less criticism when the first case of Ebola spreading from one person to another on American soil occurred. Second, recognizing plurality in the crisis narrative, in this case, advanced from a right to a necessity. The National Nurses United spoke on behalf of nurses who were genuinely fearful that the existing protocols were not sufficient. This example points to the vital importance of hearing all voices in the evolution of a crisis narrative. Conversely, divergence in crisis narratives can originate from less genuine or sincere concerns. Some argued that much of the controversy emerging about the trustworthiness of the CDC and President Obama to manage the Ebola risk was little more than political manipulation. The challenge for crisis communicators is to acknowledge such criticism during health-related crises, but to do so in a manner that prioritizes the well-being of those at risk. Quarreling publicly without such emphasis on those who are or feel they are at risk is likely to promote rather than resolve narrative divergence.

p.332

The surprise, threat, and uncertainty of Ebola created a void of understanding and meaning. This communication vacuum and meaning deficit was filled with narratives about the risk. In June of 2016, the WHO officially declared the West Africa Ebola outbreak over. A total of eight cases were confirmed in the US and six of those contracted the disease in West Africa. Only two cases of infection occurred in the US. These were a consequence of ineffective protection in the treatment of the first case, Thomas Eric Duncan. While the official narrative proved most accurate, the divergent narrative created a great deal of concern, confusion, and uncertainty, and diverted resources and attention. Crisis managers, however, should always anticipate and prepare for divergent narratives, as these appear to be an inevitable part of the crisis story.

Organizations and agencies can take several practical steps to prepare for diverging and highly critical narratives. An initial step in preparing for divergent narratives is to understand in advance of a crisis how to track the emerging narrative accurately and determine how the organization can best assert itself into the evolving narrative. Organizations and agencies might ask the following questions: Who are our critics? Where do these critics typically voice their opposition? What access does my organization or agency have to this forum? Second, organizations can prepare for divergent narratives by following the standard best practice of working with media reporters well before any crisis occurs (Seeger, 2006). Having a network in place that includes reporters, from both legacy and new media sources, who cover the issues relevant to the organization or agency is essential for making a timely response to crises and having a presence in the crisis narrative from the outset. Third, organizations should be prepared to determine when and if a diverging narrative is significant. Not all divergent narratives warrant a response (Coombs & Holladay, 2012). If a critical narrative is emerging, but the audience is limited or the source is highly questionable, responding to the criticism may only draw attention to a nonissue. These manageable steps can help organizations plan for crises. As is so often the case in crisis communication, failing to develop a comprehensive crisis communication plan can cause devastating delays and diminish the ultimate effectiveness of a response.

p.333

Competing narratives are an inherent element of the sense-making process that occurs during and after crises. The Ebola crisis simultaneously created public alarm and uncertainty. Combined, these conditions created an atmosphere where diverging narratives could thrive. Additionally, the Ebola crisis dramatically revealed that planning and resources did not account for many risks with the disease. When cases moved from Africa to the United States, this lack of preparation was distressingly clear. The hope is that this dramatic crisis will inspire organizations and agencies to collaborate and coordinate their efforts and to dedicate sufficient resources in their preparations for such fear-provoking disease outbreaks in the future.

References

Anthony, K. E., Sellnow, T. L., & Millner, A. G. (2013). Message convergence as a message-centered approach to analyzing and improving risk communication. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41(4), 346–364.

Barrett, T., & Walsh, D. (2014, October 3). Ebola becomes an election issue. CNN.com. Retrieved from www.cnn.com/2014/10/03/politics/ebola-midterms/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015, December 10). What you need to know about Ebola. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/what-need-to-know-ebola.pdf.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, J. S. (2012). The paracrisis: The challenges created by publicly managing crisis prevention. Public Relations Review, 38, 408–415.

Fisher, W. R. (1987). Human communication as narration: Toward a philosophy of reason, value, and action. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Goodnight, G. T. (1999). The personal, technical, and public spheres of argument. In Contemporary Rhetorical Theory: A reader, 251–264. New York: The Guilford Press.

Harlan, C. (2014, October 15), An epidemic of fear and anxiety hits Americans amid Ebola outbreak. The Washington Post. Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/an- epidemic-of-fear-and-anxiety-hits-americans-amid-ebola-outbreak/2014/10/15/0760fb96-54a8-11e4-ba4b-f6333e2c0453_story.html?utm_term=.7f954f9c6b80.

Heath, R. L. (2004). Telling a story: A narrative approach to communication during crisis. In D. Miller & R. Heath (Eds.), Responding to crisis: A rhetorical approach to crisis communication, 167–188. Mahwah, NJ: LEA.

Obama, B. (2014). Remarks by the President on the Ebola outbreak. The White House. Retrieved from www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/16/remarks-president-ebola-outbreak.

Osterholm, M. (2014). What we are afraid to say about Ebola. The New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2014/09/12/opinion/what-were-afraid-to-say-about-ebola.html.

p.334

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The new rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation. Trans. John Wilkinson and Purcell Weaver. London: University of Notre Dame Press, 31, 33.

Peters, C. J., & Peters, J. W. (1999). An introduction to Ebola: the virus and the disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 179(Supplement 1), ix–xvi.

Seeger, M. W. (2006). Best practices in crisis communication: An expert panel process. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 34, 232–244.

Seeger, M., & Sellnow, T. (2016). Narratives of crisis: Telling stories of ruin and renewal (Vol. 19). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Sellnow, T. L., & Seeger, M. W. (2013). Theorizing crisis communication (Vol. 4). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sellnow, T. L., Ulmer, R. R., Seeger, M. W., & Littlefield, R. S. (2009). Effective risk communication: A message-centered approach, 19–31. New York: Springer.

Ulmer, R. R., & Sellnow, T. L. (2000). Consistent questions of ambiguity in organizational crisis communication: Jack in the Box as a case study. Journal of Business Ethics, 25, 143–155.

Ulmer, R. R., Sellnow, T. L., & Seeger, M. W. (2013). Effective crisis communication: Moving from crisis to opportunity. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Venette, S. J., Sellnow, T. L., & Lang, P. A. (2003). Metanarration's role in restructuring perceptions of crisis: NHTSA's failure in the Ford-Firestone crisis. The Journal of Business Communication, 40(3), 219–236.