FUNERAL SERVICE AND STRESS: CARING FOR THE CAREGIVER

“Without work all life goes rotten. But when work is soulless, life stifles and dies.”

Author Unknown

THE FUNERAL DIRECTOR AND STRESS

A growing awareness is occurring within funeral services of the enormous cost of employees’ dissatisfaction both for the individual and the funeral home. For the good of the profession the time has come to focus some efforts on “how to care for the funeral director as caregiver” (Wolfelt, 1989a; 1989b).

Without a doubt, few vocations are more challenging, or more rewarding, than the opportunity to work in funeral service. However, few funeral directors can avoid the special stress that comes with entering into this important field of service.

Assisting people before, during, and after the funeral is a demanding interpersonal process that requires energy, focus, and desire to understand. Working with people in grief forces you to confront your own losses, fears, hopes, and dreams surrounding both life and death.

Whenever you attempt to respond to the needs of people in grief, the chances are slim that you can, or should, avoid the stress of emotional involvement. The key is what you choose to do with the stress and the art of learning how to not only care for others, but yourself.

As you work with people in grief, you open yourself to care about them and their personal journey of mourning. Genuinely caring about the mourner and sharing with him or her some of the most difficult of times in life touches the depths of your own heart and soul.

Specific causes of stress can originate from a variety of sources. Funeral service continues to change rapidly, and change by its nature means stress. Other stresses include intermittent interruption of schedules, the discovery of churned-up feelings related to personal loss of friends and family, time spent away from family and friends, and unrealistic expectations about people always appreciating the value of the service you have to offer.

The result of these influences is potentially what we might term FUNERAL SERVICE BURNOUT. Symptoms of this burnout syndrome often include the following:

1. exhaustion and loss of energy,

2. irritability and impatience,

3. cynicism and detachment,

4. physical complaints and depression,

5. disorientation and confusion,

6. omnipotence and feeling indispensable, and

7. minimization and denial of feelings.

The purpose of this chapter is to outline these stress-related signs and symptoms. In addition we will address how funeral directors can strive to take care of themselves and avoid becoming “wounded healers.”

Feelings of exhaustion and loss of energy are usually among the first signals of funeral director stress. Low energy and fatigue for the funeral director is often difficult to acknowledge because this is the opposite of the high energy level required to meet demands that are both self-imposed and experienced from the outside.

Our bodies are powerful instruments and frequently much wiser than our minds. Exhaustion and lack of physical and psychic energy are often unconscious “self cries for help.” Now, if we could only slow down and listen to the temple within.

As stress builds from within, irritability and impatience become inherent components of the experience of “funeral service burnout.” As an effective helper, you have typically experienced a sense of accomplishment and reward for your efforts. As stress increases, the ability to feel reward diminishes while your irritability and impatience become heightened.

Disagreements and tendencies to blame others for any interpersonal difficulties may occur as stress takes its toll on your sense of emotional and physical well-being. A real sign to watch for is that you have more care to give the families you serve than you have compassion and sensitivity to the needs of your own family.

As funeral directors experiencing emotional burn-out, you may begin to respond to stress in a manner that saves something of yourself. You may begin to question the value of funeral service, of your family life, of friendships, even of life itself. You may work to create distance between yourself and the families you are serving.

You may work to convince yourself, “There is no point in getting involved” as you rationalize your need to distance yourself from the stress of interpersonal encounter. Detachment serves to help distance yourself from feelings of pain, helplessness, and hurt.

PHYSICAL COMPLAINTS AND DEPRESSION

Physical complaints, real or imagined, are often experienced in funeral directors suffering from burnout. Sometimes, physical complaints are easier to talk about than emotional concerns. The process of consciously or unconsciously converting emotional conflicts may result in a variety of somatic symptoms like headaches, stomachaches, backaches, and long-lasting colds. These symptoms are direct cues related to the potential of stress overload.

Generalized feelings of depression also are common to the phenomenon of “funeral service burnout.” Loss of appetite, difficulty sleeping, sudden changes in mood, and lethargy suggest that depression has become a part of the overall stress syndrome. Depression is a constellation of symptoms that tell you something is wrong to which you need to pay attention and work to understand.

Feelings of disorientation and confusion are often experienced as a component of this syndrome. Your mind may shift from one topic to another, and focusing on current tasks often becomes difficult. You may experience “polyphasic behavior,” whereby you feel busy, yet do not accomplish much at all. Since difficulty focusing results in a lack of personal sense of competence, confusion only results in more heightened feelings of disorientation.

Thus, a cycle of confusion resulting in more disorientation evolves and becomes difficult to break. The ability to think clearly suffers, and concentration and memory are impaired. In addition, the ability to make decisions and sound judgements becomes limited. Obviously your system is overloaded and in need of a break from the continuing cycle of stress.

OMNIPOTENCE AND FEELING INDISPENSABLE

Another common symptom of what this author has termed “funeral service burnout” is a sense of omnipotence and feeling indispensable. Statements like, “No one else can make arrangements like I can,” or, “I have got to be the one to help all those people in grief’ are not simply the expressions of a normal ego.

Other funeral directors can be helpful to families and may do it very well. This author acknowledges that in a small firm you may be the only one available.

However, if you as a funeral director begin to feel indispensable, you typically block your own, as well as others’, growth. Thinking that no one else can provide adequate help to families but oneself is, among other things, often an indication of stress overload.

MINIMIZATION AND DENIAL OF FEELINGS

Some funeral directors when stressed to their limits continue to minimize, if not deny, feelings of burnout. The person who minimizes is aware of feeling stressed, but when felt, works to minimize the feelings by diluting them through a variety of rationalizations. From a self perspective, minimizing stress seems to work, particularly because it is commensurate with the self-imposed helping principle of “being all things to all people.” However, internally repressed feelings of stress build within and emotional strain results.

Perhaps the most dangerous characteristic of the “funeral service burnout syndrome” is the total denial of feelings of stress. As denial takes over, the funeral director’s symptoms of stress become enemies to be fought instead of friends to be understood. Regardless of how loud the mind and body cry out for relief, no one is listening.

The specific reasons funeral directors adopt denial of feelings of stress are often multiple and complex. For the purposes of this article we will note that when you care deeply for people in grief, you open yourself to your own vulnerabilities related to loss issues. Perhaps another person’s grief stimulates memories of some old griefs of your own. Perhaps those you wish to help through the experience of the funeral frustrate your efforts to be supportive.

Whatever the reason, the natural way to prevent yourself from being hurt or disappointed is to deny feelings in general. This denial of feelings is often accompanied by an internal sense of a lack of purpose in what you are doing. After all, the willingness and ability to feel are ultimately what gives meaning to life.

This outline of potential symptoms is not intended to be all-inclusive or mutually exclusive. The majority of overstressed funeral directors will experience a combination of symptoms. The specific combination of symptoms will vary dependent on such influences as basic personality and outside influences.

Of all the stresses inherent in funeral directors, emotional involvements appear central to the potential of suffering from burnout. Perhaps we should ask ourselves what we lose when we decide to minimize or ignore the significant level of emotional involvement that occurs when working in funeral service.

We probably will discover that in the process of minimizing or ignoring we are, in fact, depleting our potential to help of this most important component: the all powerful reality that caring about people in grief while at the same time caring for oneself is vital to helping people during these difficult times. While the admirable goal of helping others may seem to justify emotional sacrifices, ultimately we are not helping others effectively when we ignore what we are experiencing within ourselves.

If you acknowledge that effective interpersonal helping is always tied to the relationship you establish with families served, then you also must focus on yourself as you are involved with the people you are assisting. This relates to the demanding dual focus that is essential to being an effective funeral director to the bereaved. As the saying goes, “If you want to help others, the place to start is with yourself.”

Experience suggests that practice is needed to work toward an understanding of what is taking place inside yourself while trying to grasp what is taking place inside others. After all, these thoughts and feelings occur simultaneously and are significantly interrelated.

Obviously, you cannot draw close to others without beginning to affect and be affected by them. This is the nature of helping relationships with bereaved families. We cannot help others from a protective position. Helping occurs openly where you are defenseless, if you allow yourself to be. Again, this double focus on the mourner and on oneself is essential to the art of being an effective funeral director.

As caregivers to the living and the dead, an important recognition is that on occasion you too may need a supportive relationship where you can be listened to and accepted—to recharge your emotional battery. Few people who have ever tried to respond to the needs of others in a helping relationship have escaped the stress that comes from emotional involvement.

Involving yourself with others, particularly at a time of death and grief, requires taking care of oneself as well as others. Emotional overload, intermittent interruption of schedules, circumstances surrounding deaths, and caring about people will ultimately result in times of “funeral service burnout.” When this occurs, you should feel no sense of inadequacy or stigma if you also need the support and understanding of a caring relationship. As a matter of fact, you should be proud of yourself if you care enough about “caring for the funeral director as a caregiver” that you seek out just such a relationship!

AM I EXPERIENCING FUNERAL SERVICE BURNOUT?

Very little documented research is available that compares levels of stress and potential burnout across different professions. However, the general concensus is that funeral directors experience burnout on a routine basis.

A funeral director recently inquired, “How is burnout different from stress?” We might overhear someone comment, “I’m really feeling burned-out today.” All of us may have occasional days when our motivation and energy levels vary. While this fluctuation in energy states is normal, burnout is an end stage that typically develops over time. Once a person is “burned-out,” dramatic changes become vital to reversing the process.

Psychologist Christina Maslach (1982), a leading authority on burnout, has outlined three major qualities of burnout.

Emotional Exhaustion—feeling drained, not having anything to give even before the day begins.

Depersonalization—feeling disconnected from other people, feeling resentful and seeing them negatively.

Reduced Sense of Personal Accomplishment—feeling ineffective, that the results achieved are not meaningful.

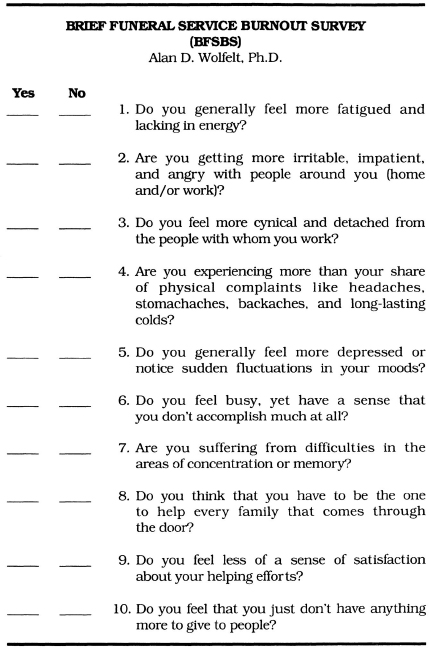

Step back for a moment and complete what we will term the “Brief Funeral Service Burnout Survey” (BFSBS) provided in Figure 22.1. As you review your life over the past 12 months answer the survey questions.

To monitor your potential for burnout, ask yourself to how many of these questions you answered “yes.” In general, if you answered “yes” to two to four of these questions, you are standing too close to the fire. If you answered “yes” to five to seven of these questions, call the fire department because you’re burned-out. If you answered “yes” to eight to ten of these questions, your feet are in the flame.

Figure 22.1. Brief Funeral Service Burnout Survey (BFSBS).

GUIDELINES FOR CARING FOR THE FUNERAL DIRECTOR

The following practical guidelines are not intended to be all-inclusive. Pick and choose those tips that you believe will be of help to you in your efforts to stay physically and emotionally healthy.

Remember, our attitudes in general about stress and burnout sometimes make it difficult to make changes. However, one important point to remember is that with support and encouragement from others, most of us can learn to make positive changes in our attitudes and behaviors.

You might find that having a discussion among coworkers about this topic of funeral service burnout is helpful. Identify your own signs and symptoms of burnout. Discuss individual and group approaches to self-care that will help you enjoy both work and play!

The following guidelines can be meaningful in assisting you to prevent burnout. Reread these guidelines frequently to help yourself reassess development and performance:

1. Recognize that you are working in an area of care where the risk of burnout is high. While working in funeral service has its rewards, it also has its dangers. Keeping yourself aware that you are “at risk” for burnout will help keep you from denying the existence of stress-related signs and symptoms.

2. Create periods of rest and renewal. The quickest way to burnout is spreading yourself too thin—trying to help too many people or taking on too many tasks. Learn to respect both your mind and body’s needs for periods of rest after helping other people.

3. Be compassionate with yourself about not being perfect. After all, none of us are! As people who like to help others, we may think our helping efforts should always be successful. Some people will reject your help while others will be invested in minimizing the significance of your help. This is particularly true in people who do not perceive value in having a funeral service. Also remind yourself that mistakes are an integral part of learning and growth, but are not reflections of your self-worth.

4. Practice setting limits and alleviate stresses you can do something about. Work to achieve a clear sense of expectations and set realistic deadlines. Enjoy what you do accomplish in helping others, and do not berate yourself for what is beyond you.

5. Learn effective time-management skills. Set practical goals for how you spend your time. Don’t allow time to become an enemy. When working on projects remember Pareto’s principle: 20 percent of what you do nets 80 percent of your results.

6. Work to cultivate a personal support system. A close personal friend can be a real lifesaver when it comes to managing stress and preventing burnout. If you have already reached the crisis state of burnout, realize that you may well need the help of others in making life-style changes. Many funeral directors have trouble asking for help. If this is the case for you, practice giving yourself permission to seek outside support. Remember, recent research has demonstrated that human companionship and connectedness helps you live longer.

7. Express the personal you in both your work and play. Don’t be afraid to demonstrate your unique talents and abilities. Make time each day to remind yourself of what is important to you. Act on what you believe is important. If you only had three months to live, what would you do? Use this question to help determine what is really important in the big picture of life and living.

8. Work to understand your motivation to work in funeral service. Does your need to help others with grief relate in any way to your own unreconciled losses? If so, be certain not to use your helping relationships to work on your own grief. Find trusted resources to help you work with any old and new losses.

9. Develop healthy eating, sleeping, and exercise patterns. We are often aware of the importance of these areas for those we help; however, as caregivers we sometimes neglect them ourselves. A well-balanced diet, adequate sleep, and regular exercise allows for our own physical, mental, and emotional well-being.

10. Strive to identify the unique ways in which your body informs you that you are stressed. Do you get tightness in the shoulders, backaches, headaches? Becoming conscious of how your body communicates stress signals to you allows for awareness of stressful situations before they overwhelm you. A constant state of physical tension often results in deterioration, which results in physical breakdown.

Again, be aware that the above practical guidelines are not intended to be all-inclusive. This author suggests that you and your colleagues develop your own list of how to prevent and work with “funeral service burnout.”

Each one of us has our own unique style of relating to the stresses of living. Sometimes we manage those stresses well, while at other times we need people who care about us to help us to acknowledge the potential of burnout. Hopefully, this chapter will assist you in assessing your own stress level and, if appropriate, help you begin to make some changes.

No doubt exists in this author’s mind and heart that to work in funeral service is a true privilege. Perhaps we can be proud that we want to help make a difference in people’s lives, while at the same time remembering the importance of taking care of ourselves as caregivers.

Caring about our life’s work, even enjoying it, will probably seem strange if we only see it as a way to make a living. However, if we can see our work as a way to enrich each moment of our living, we may well discover a deep caring within our souls that teaches us to learn and grow each and every day.

PERSONAL SIGNS OF STRESS AND SELF-CARE STRATEGIES

Directions

Form small groups of three to five people. Each person can express three personal symptoms that they know they experience when stressed. Each person will then list three self-care strategies that he or she uses to manage stress.

Expectations

By sharing personal symptoms and management strategies group members will gain new insights into stress producers and means to prevent burnout.

After reading and participating in the activities related to this chapter you should be able to (1) outline several specific causes of stress in funeral service, (2) identify seven stress-related signs and symptoms, (3) acknowledge if you are personally experiencing “funeral service burnout,” and (4) discuss practical self-care guidelines for surviving stress and enjoying life!

Maslach, C. (1982). Understanding burn-out: Definitional issues in analyzing a complex phenomenon, in W.S. Paine (Ed.). Job stress and burn-out. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Wolfelt, A.D. (1989a). Funeral service burn-out: Signs and symptoms. The Director, November.

Wolfelt, A. (1989b). Survival techniques. The Director, December.

To receive a descriptive brochure of Dr. Wolfelt’s annual “Caring for the Caregiver” Seminar that is held in May of each year in the Virgin Islands, write the Center for Loss and Life Transition, 3735 Broken Bow Road, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 (Telephone 303/226-6050).