To deliver effective data visualizations, we need to understand our audience: human beings.

There are some rules that we need to know when dealing with humans. These are based on sound psychological studies, and therefore, aren't always true! They are good guidelines that apply to the majority of the population, but we really need to know that you can't please all of the people all of the time.

One of the things that humans really excel at is recognizing things that they have seen before or look similar to things that they have seen before and associating those things with other similar things that they have experienced before. As we tend to share a lot of cultural experiences, many of us will share the same generalizations. For example, you might have seen this in your Facebook or e-mail in the recent past:

"Olny srmat poelpe can raed tihs.

I cdnuolt blveiee taht I cluod aulaclty uesdnatnrd waht I was rdanieg. The phaonmneal pweor of the hmuan mnid, aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, t he olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be in the rgh it pclae. The rset can be a taotl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit a porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe. Amzanig huh? yaeh and I awlyas tghuhot slpeling was ipmorantt!"

Of course, this isn't true! Consider this sentence:

udinsnantderg lugagane sdolem egurecaons ciosonfun

In the first paragraph, the letters aren't really completely scrambled. They are close enough to the originals for us to easily read the paragraph as we scan across them and match the patterns to the words. In the second sentence, the letters are truly scrambled, and we need to try and employ our anagram-solving skills to try and understand the sentence: understanding language seldom encourages confusion.

The process of seeing patterns in things that might otherwise be considered random is called apophenia. It is something that we do a lot because we are very good at it. Imagine driving down the freeway and seeing a cloud ahead of you.

What do you see? Is it merely a collection of water droplets, floating on air currents? Or is it a dragon, flying through the sky? It could be anything. To each of us, it is whatever our brains make of it, whatever pattern we match.

We are fantastic at seeing these pictures. We have a large proportion of our brain devoted to the whole area of visuals and matching patterns against our memory, far bigger than for any other sense.

We, as humans, don't have a very long history with numbers. This is because for very long stretches of our evolution, we just didn't need number systems. As hunter-gatherers, it was not necessary for us to count accurately. All we needed to do was make estimations.

We can still see this today in surviving hunter-gatherer tribes such as the Warlpiri in Australia and the Munduruku in the Amazon. Both tribes have words in their languages for small numbers such as one, two, or three, but after that they either have no words at all or have some words but are inconsistent in their use.

About 10,000 years ago, things started to change. Although there is evidence of limited agriculture in surrounding areas, the real changes happened in and around an area known as Fertile Crescent (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fertile_Crescent), an area sitting between the Nile Delta in the southwest, the Caspian Sea in the northeast, the Black Sea in the northwest, and the Persian Gulf in the southeast. The main rivers of this area, Tigris, Euphrates, and Nile, created a large area of fertile land and agriculture and husbandry of animals exploded. Man started changing from hunter-gatherer to farmer and shepherd.

As we settled down, we started trading with each other. Suddenly, we came up with a reason to count things! When we went to bed with one hundred sheep in the field, it was important to know that there were one hundred sheep still there in the morning.

Given that we have had up to a million years of evolution, it might not be too far a stretch to say that most humans are not as comfortable with numbers as they think.

How many dots are in the upper circle?

How many dots are in the lower circle?

Now, consider how you answered both those questions. I would suggest that most people will look at the upper circle and immediately see two dots. However, when most people look at the second circle, they will not immediately see eight dots. Instead, they will often switch to breaking the number down, perhaps see three + two + three (vertically), three + three + two (horizontally), or some other breakdown, and then add those back up to get the number eight. Even for such a relatively small number such as eight, we still tend to break it down into smaller groups. So, how can we count this number of dots?

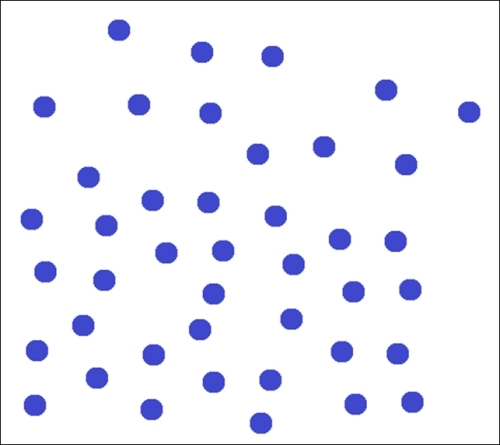

Of course, we can't count these in one go. We could spend a minute counting them one by one, although we still might not get the correct answer as the random arrangement could lead to mistakes. Alternatively, we could just have a guess and estimate the correct answer. Wouldn't that be good enough for most situations? It would be especially good enough if our goal is just to answer the question of which side has more dots:

If we have to answer the question with any sort of immediacy, we need to quickly estimate and decide. Quite often though, we will get the right answer! Our brains are actually very good at this estimation, and it comes from a time a long way before numbers existed.

When deciding where to spend valuable energy to chase down or gather food, early man would have had to make the calculations on return on investment. All of these would have been done by estimations: how many wildebeests are there in the herd, how far it was to get to them, or how many people are needed to hunt them down. We still do this today! If we walk into a fast-food restaurant at lunchtime, and you see eight long queues of people waiting to be served, we immediately start making evaluations and estimations about which queue should be the one for us to spend our valuable time in to get the reward; otherwise, we estimate that it is not worth spending time for that reward and we leave.

So, knowing that we are naturally good at estimation, how does this help when we are working with numbers—something that we have, relatively, spent a lot less time with?

It would appear that when it comes to numbers, we still perform estimations. When we see two numbers beside each other, especially large numbers, our brains will make estimates of the size of the numbers and create a ratio, though not always accurately. Let's consider this famous set of numbers:

Anscombe's Quartet, created in 1973 by the statistician, Francis Anscombe

Just spend a minute perusing the numbers and see whether you can see anything interesting in them.

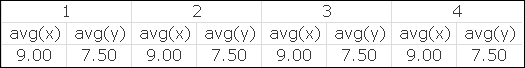

They look reasonably similar. We might think about doing some analysis of the data to see whether there is a major difference. Perhaps, we should average them:

Quite interestingly, it appears that each set of columns has the same average for the X and Y values. Perhaps, we should look at the standard deviation:

Again, it appears that we have a very similar dataset indeed. Perhaps, we should calculate the slope of the regression line for these numbers:

Statistically speaking, this is a remarkably similar dataset. I wonder how this dataset would look if we actually graphed it:

Incredible! We have a dataset that looks quite similar on casual inspection, and even more so when we apply common statistical functions, but when we graph it we can see that it is completely different!

There have been many studies into the picture superiority effect, where it is shown that we understand and learn far better using pictures than words. For example, a study by Georg Stenberg of Kristianstad University, Sweden, in 2006, entitled, Conceptual and perceptual factors in the picture superiority effect, looked at memory superiority of pictures over words.

Every study will show that we remember pictures better and that we can associate pictures with other memory items better; we just process visual images faster than spoken words or sentences written on a page.

A larger portion of our brain's cortex is devoted to visuals as opposed to every other sense. This shouldn't be a surprise as we are a relatively slow and weak animal with an inferior sense of smell and hearing compared with other animals. Our vision and our ability to process visuals is one of the things that has made us the dominant species on this planet.

So, we know that humans are excellent pattern matchers. We can see patterns in shapes and create stories from those patterns that match our experiences. However, we are not really that great with numbers. We like to think that we are, but we often fail to see patterns in sets of numbers.

We are quite comfortable with very small numbers, but even with slightly bigger numbers, we will adopt a strategy of breaking them down to smaller parts to help us understand.

We don't really get exact numbers unless we can directly experience them. For example, for many of us, the phrase, "20 minutes", has no real meaning whereas the phrase, "about 20 minutes", is immediately understood! This is because we have no natural reference point for exactly how long a second or a minute is, let alone 20 minutes, but we can reference our experience and understand exactly how long about 20 minutes is.

So, if humans are not very good at dealing with exact numbers, what is the most effective way of communicating with numbers? We cannot rely on people gaining insight from a column of numbers in a spreadsheet. The only way to help us understand numbers is to present them graphically and in context.

We really need to show people the numbers.