Designing Together:

The Power of ‘We Think’,

‘We Design’, ‘We Make’

‘The purpose of (co-)design is the creation of new societal values to balance human happiness with ecological truths. In doing so design contests the notion of material and economic progress, and its inherent ecological untruths.’

Alastair Fuad-Luke

The phenomenon of globalization1 has produced a profound shift in societal perceptions and behaviour, especially in the current 1.4 billon internet users. Since the 1970s, a redrawing of the distribution of industrial, post-industrial and recently industrialized societies has occurred. The past ten years have seen even more radical shifts in this distribution. European politicians gradually acknowledged that the centre of gravity of the industrialized world had moved from Europe to East Asia, towards China in particular. This shift in the global industrial axis is permissible because of cheap labour in certain parts of the world and the ability for rapid flows of people, money, raw materials, finished products, information and ideas. Technology, especially ICT, has added new facets to the Postmodern space–time compression articulated by Charles Jencks.2 Simultaneous conferencing, chatting, trading, gambling, blogging and sex are 365/24/7 everyday internet pastimes. Telephony networks intensify their geographic reach worldwide enabling a leapfrogging from ‘no landline phone’ to ‘mobile phone’. Under these circumstances there should be little wonder that the notions of designing and manufacturing established in the 19th century, honed in the 20th century and taken as the norm a mere decade ago, are facing a period of ‘massive change’, a phrase coined by Bruce Mau.3 The speed of the transition is remarkable and hardly permits time to catch breath. There’s no time to experience the phenomenon that Alvin Toffler observed in 1965, called ‘future shock’ – ‘the shattering stress and disorientation that we induce in individuals by subjecting them to too much change in too short a time’.4 We become desensitized to change as a new manifestation of globalization is joined, hybridized or is superseded by yet another manifestation. Change has been normalized and so has the rapid tempo of daily life. The reaction to this real and perceived speed of contemporary life is the ebullient rise of a ‘slow’ counter-movement,5 the aforementioned flows of the real and intangible are also generating fresh opportunities, exchanges, alliances, social phenomena and genuine philanthropic positive change. People and ideas are blending, and clashing, in unpredictable ways. The flows are fast, furious and diverse. Design has a pivotal role in controlling the metabolism of these flows, as noted by John Wood (Figure 5.1).6 Design mediates the flows of natural, financial, manufactured, man-made, symbolic and cultural capitals. Intervening to rechannel the amount and direction of these flows provides fertile ground for any design activist.

Figure 5.1

Design, the wise regulation of dynamic elements

Dealing with ‘Wicked Problems’

Sustainability could be defined as a ‘wicked problem’, a problem first characterized by Horst Rittel in the 1960s as ‘a class of social system problems which are ill-formulated, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values, and where the ramifications of the whole system are thoroughly confusing’.7 Rittel’s thinking has recently, and deservedly, been re-examined.8 Problem definition is itself subjective as it originates from a point of view, therefore all stakeholders’ points of view are equally knowledgeable (or unknowledgeable) whether they are experts, designers or other actors.9 Rittel is an advocate of designing together because people have to dialogue, agree on how to frame the problem, agree goals and actions, and this argumentative process is inherently political, in fact design is political,10 a view supported by Guy Bonsiepe, who defines political in the sense of a societal way of living rather than narrow party politics.11 If sustainability is the most challenging wicked problem of the current era, then participation in design, as a means to effect deep, transformative, socio-political change, seems essential. This suggests a significant new direction for design to seize.

The Rise of Co-creation, Co-innovation and Co-design

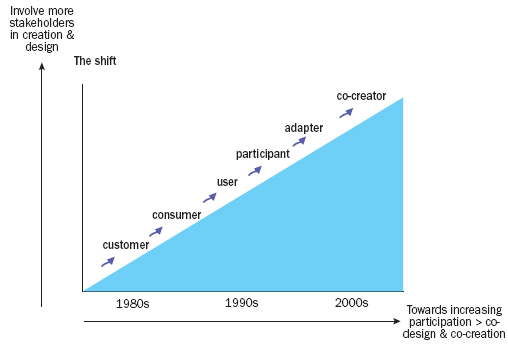

Since the 1980s there has been a shift in attitude of certain business sectors towards its customers. The realization that the creative potential of these very same customers can help business create better services and products has encouraged the development of a range of methodologies to tap this potential. The language has shifted, as noted by Liz Sanders of US design agency SonicRim, who was an early pioneer in revitalizing participatory design approaches12 from designing for users to designing with users, from customer to user to co-creator (Figure 5.2). This shift has been paralleled with a resurgent debate about the social dimensions of design,13 the role of the internet in opening up new opportunities for design/designing,14 a widening of ecological reform to embrace technocratic to strong democratic approaches,15 and the shifting canvas of design praxis.16 Now that the participatory genie is out of the bottle, designers need to get a firm grip on what it means for the design profession and how it can be engaged effectively for design activism. One particularly important dimension is how intellectual property (IP) is protected in this participatory culture. A balance needs to be struck between commercial appropriation and the creation of a genuine commons of knowledge and know-how.

Figure 5.2

The shift from customers to co-creators

The open source and open design movements

Academics, science and technology specialists have long held the principles of openness, peer review and co-operation as essential to advancing a particular canon(s) of philosophy, thought and action. It was this desire that originated ARPANET, the first ICT network to enable communication between University College Los Angeles (UCLA) and Stanford Research Institute International in California in 1969.17 ARPANET is a key ancestor of the internet as we know it today. The arrival of personal computers (PCs) on the office desktop in the 1980s gave significant impetus to improving connectivity and communication between PC users, locally and globally to facilitate collaboration and exchange of information. The development of appropriate communication protocols enabling computers to ‘talk’ to each other more easily moved rapidly and, by the late 1980s, the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) was firmly established. This encouraged the joining together of more networks. By the early 1990s these networks had gained a new public interface, the World Wide Web, based on web browsers and hypertext mark-up language (html) developed by Tim Berners-Lee.18 The possibilities for the dissemination of information and collaboration made a step-change. More recent emergence of internet technologies such as chat rooms, blogs and wikis has provided further opportunities for collaboration.

Parallel to the development of the internet in the 1980s was the development and sharing of free software. This software is frequently developed by collaboration within a group or groups of people, freely committing their time, knowledge and skills to build and test the software then offer it for free usage (usually with specific or general conditions attached). A general definition of ‘open source’ refers to a ‘product’ comprising source code, design documents and/or content that users have permission to use.19 Open source has a variety of expressions being applied to ‘products’ such as software (e.g. operating systems such as Linux; internet browsers such as Mozilla Firefox; content management systems such as Moodle for educational uses), hardware, games and, more recently, music, but it is also extended to embrace particular expressions of democracy – open source content (e.g. Wikipedia the online encyclopedia), governance, government and politics.20 Where there is an open source ‘product’, various licences may specify the exact terms of use, but the overriding principle is that some or all of the knowledge within the ‘product’ is made available for the common good and is not retained as closed source, proprietary intellectual property which is controlled by the owners. Two of the most successful examples of open source collaboration comprise the worldwide communities that have developed, and continue to develop, and support Linux – an operating system software whose development started with Linus Torvalds in Helsinki in 199121 – and Wikipedia founded by Larry Sanger and Jimmy Wales in 2001.22

The World Wide Web is a socio-cultural project whose ramifications are still unfolding, but advocates of its ability to democratize the sharing of knowledge and creativity, indeed to significantly alter the way we collaborate, make and shape the world,23 see nascent opportunities for mass collaboration, innovation and production. The term ‘open design’ has recently joined the internet lexicon as ‘the investigation and potential of open source and the collaborative nature of the internet to create physical objects’.24 The success of open source is now stimulating not-for-profit ‘.orgs’ and commercial companies to foster collaboration to tackle global problems. Diverse organizations from the global design diaspora are seeing the potential of web-led technologies for donative, altruistic design work (see Chapter 6, pp169–175). The internet facilitates interdisciplinary ways of working. For example, Designbreak is an advocacy group for open design bringing together scientists and engineers to tackle environmental degradation and raise standards of living and access to medicines for the poor in developing countries.25

The intellectual commons

Earning a living as a designer, especially for the typical European design practice which aptly fits the descriptor of ‘micro-enterprise’ (one or two people) or ‘small and medium-sized enterprise’ (SME), which for the average European company comprises eight to ten people, is difficult if the IP of a design cannot be given some protection in a competitive global marketplace. However, there are advantages in not protecting all of one’s creative work. Computer scientists, hardware engineers and software writers have long enjoyed gainful employment, working under strict IP environments, while enjoying parallel working with more altruistic goals and more open IP environments. The latter provide collaboration in open source projects and help build essential skills that enhance the professional in his/her ‘employed’ positions. The emergence of Linux as a commercially viable operating system for computers is a successful example of how open IP environments can actually challenge and win business from the closed IP environments of transnationals. Charles Leadbeater notes that Linux and Wikipedia, which are challenging the established copyright paradigms, rely on a core or kernel of active experts, a large interested cohort of active participants, and an even larger audience of passive recipients.26

There is a fundamentally more important reason as to why we should look after and improve the health of the open source IP environments – sustainability is such a complex mix of connected problématiques that it can only succeed with extensive local, regional, national and international co-operation using the knowledge and know-how embedded in different geographies and cultures. This requires an openness and willingness to share knowledge, experience and wisdom. This condition is recognized by a number of organizations that have invested much effort and attention to modernize the debate on IP in the ‘information age’.

Contestation of modern IP law goes back to the 1970s cultural Zeitgeist of sharing, openness and collaboration. In October 1976, Li-Chen Wang and Roger Rauskolb issued a software program in BASIC computer language for the Palo Alto Tiny BASIC with an Intel 8080 microprocessor (‘chip’) with the following copyright statement, ‘@Copyleft. All Wrongs Reserved’, a complete reversal of the legally enshrined, ‘©Copyright. All Rights Reserved’.27 Today there are a number of copyleft licences, some with stronger copyleft tendencies than others. GNU General Public License is a popular free software licence28 and the Design Science License is suitable for non-software works including art, music, photography and video.29 Copyleft licences require that all subsequent and derived works are copyleft too, and in doing so there is a concern to prevent the re-appropriation of copyleft work by private interests that wish to gain proprietary control over the IP. The copyleft movement has been joined by a sophisticated operator in recent years: Creative Commons, a not-for-profit organization founded in 2001 by Molly van Houweling, the then president, and a board of directors including Lawrence Lessig, published its first set of Creative Commons licenses in December 2002.30 Since then Creative Commons has developed and published a wide variety of licences some of which recognize the different needs of the scientific, educational and other communities.

Creative Commons ‘defines the spectrum of possibilities between full copyright– all rights reserved – and the public domain – no rights reserved. Our licenses help you keep your copyright while inviting certain uses of your work – a “some rights reserved” copyright.’

Creative Commons, September 2008

The debate around Creative Commons is fast and furious, with some critics arguing that it facilitates corporate co-option of creativity31 and others noting that the licensed Creative Commons is not an autonomous, productive commons owned by the people for the people.32 Pasquinelli also includes his and others’ observations about Copyfarleft, a system that only allows commercial use of public domain works by other workers and small co-operatives that do not exploit wage labour.33

The message is clear, any designer considering a work of design altruism needs to think carefully about the target beneficiaries and how they may have access to use (or be denied use of or have restricted access to) the designer’s IP. It is advisable to inform oneself of the appropriate IP framework and licences prior to proceeding to design using a participatory approach, although the final decision on IP protection (by individuals, groups, organizations or the commons) may need to be made during the design process by the participants.

Design Approaches that Encourage Participation

The inherent nature of design as a human activity is that it is, in general, deeply socially orientated,34 involving a variety of actors in the chain of events from contextualization of the problématique, ideation, conceptualization, detailed design, making or construction, operation or use, and after-life or reuse. Moreover, participation emancipates people by making them active contributors rather than passive recipients. It is therefore a form of design humanism aimed at reducing domination.35 Participation in design meets the human ideal of mutual support or altruism, a collective instinct of humanity.36 There is an upsurge of interest in participatory design approaches, perhaps in part due to the increasing complexity of problems that all organizations face. While Nigel Whiteley37 noted over a decade ago that participation in design decision-making in consumer culture is token and effectively reduced to participation by affirmative purchasing only, there is evidence that the way the consumer/user is now being involved in the design process is subtly changing.38 There are some well-developed and emerging approaches to design that place particular emphasis on participation by diverse stakeholders and actors. The term ‘approach’ is used here to denote a combination of elements of an underlying design philosophy, processes, methodologies and tools. The level to which these elements are developed does vary.

Co-design

‘Co-design’ is a catch-all term to embrace participatory design, metadesign, social design and other design approaches that encourage participation.39 The prefix ‘co-’ is the short form of ‘com’ meaning ‘with’, and is applied to verbs, e.g. co-operate, nouns, e.g. co-operation and adjectives, e.g. co-operative. The term ‘co-design’ is used to denote ‘designing with (others)’. The underlying premise of co-design is that it is an approach ‘predicated on the concept that people who ultimately use a designed artefact are entitled to have a voice in determining how that artefact is designed’.40 Another fundamental premise is that co-design offers an opportunity for multi-stakeholders and actors to collectively define the context and problem and in doing so improve the chances of a design outcome being effective. Co-design is a commitment regarding inclusion and power, as it contests dominant hierarchically orientated top-down power structures; it requires mutual learning between the stakeholders/actors; and invokes many of the soft system methodologies described by Broadbent:41

• being an iterative, non-linear, interactive process

• being ‘action-based’ research

• involving ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches

• simulating the real world

• being useful for complex systems or problems

• being situation driven, especially by common human situations

• satisfying pluralistic outcomes

• being internalized by the system.

Co-design is at the core of a more democratic, open and porous design process and is finding expression in the business and not-for-profit sectors.42 As a design approach it can potentially generate new affordances and new values but demands a new skill set and underlying philosophical approach from designers.

Early formative steps in the co-design process led to the mutual agreement of the design context, boundaries and problem definition, and collective definition of the required design brief (Figure 5.3). Once the brief is agreed then stakeholders and actors can be central to or more peripheral to the design process – they can deliver ideation, conceptualization, prototyping or proposals, prototype or proposal selection, design specification and, finally, the detailing, implementing, construction or making of the design outcome/solution. The final phases of the co-design process involve using and experiencing the design outcome/solution, learning from the experience, and noting and giving feedback to the stakeholders and actors to enable continuous learning and redesigning.

Co-design can be initiated and led by those with professional design experience, such as architects, planners, design managers and designers, but may also be organized and facilitated by other consultants or experts, and by businesses, governmental or non-governmental organizations.43 Presently, the practice of co-design among design professionals is more advanced in architecture, especially community architecture44 and urban design planning,45 than in other design fields, although new design initiatives are emerging such as Dott 07 and System Reload.46

Co-design is imbued with political ambitions regarding power and inclusion because it invokes notions of direct, anticipatory and deep democracy,47 whereby the participants have a voice and that voice informs the design process. Co-design embraces a number of historical and emerging design approaches.

Participatory design

The early history of participatory design (PD) is shaped by its application by co-determination laws in Scandinavia and US labour laws in the 1950s aimed at empowering workers to participate in decision-making in the workplace.48 PD fitted the Zeitgeist of the 1970s when openness and collaboration were welcomed. PD was a central tenet of the writings of Ivan Illich:

‘People need not only to obtain things, they need above all the freedom to make things among which they can live, to give shape to them according to their own tastes, and to put them to use in caring for and about others.’49

PD contests top-down only decision-making and attempts to democratize it by ensuring, ‘people destined to use the system play a critical role in designing it’.50 The emphasis here is on a systemic view of design to redesign or design systems, and a means to use the design process to mediate conflicting interests arising from different perspectives (of actors or stakeholders). The PD approach specifically facilitates the design of systems, which perhaps explains its consistent use in collaboration between scientists and computer software and hardware developers and human computer interaction,51 but it has also been applied to artefacts and built environments generated by architectural and other design practice.52 PD is not a single and integral design method but according to Carroll53 involves the following dimensions:

• domains of human activity

• roles of stakeholders in a design

• types of shared design representations

• the scope and duration of participatory interactions

• the relationship of users to design activity with respect to changes in their knowledge and skill.

Figure 5.3

An idealized schematic for the co-design process

The latter dimension indicates that participation in PD leads to transformation of the participants (see below).

Modified versions of PD, such as user-centred design (see below), have been co-opted by product designers to minimize risk by maximizing ‘user fit’ and hence the market reach of new manufactured goods. However, PD is not simply about the application of methodologies to achieve a design result, it is about ‘a mindset and attitude about people’ and a belief that everyone has something to offer the design process.54 As Sanders notes, ‘Today it is not “business as usual” anymore. The rules have changed and continue to change. The new rules are the rules of networks, not hierarchies.’ This attitude mirrors a shift from the product to beyond the product, and to designing meaningful product–user relationships and experiences.55

A variant of PD is ‘transformation design’, a term coined by the now defunct RED group at the UK’s Design Council56 to describe a nascent but growing community of practice that is applying user-centred design principles to large-scale systems and services to invoke new patterns of understanding context, new methods to deal with complex problems, teams involving the core skills of product, communication, interaction and spatial designers, and an emergent philosophy. Projects where transformation design was applied demonstrate six characteristics and signal a real challenge to the notion of the designer as auteur:

• defining and redefining the brief – by understanding the scope of the issue and defining the right problem to tackle upstream of the brief

• collaborating between disciplines – by creating a neutral interdisciplinary space

• employing participatory design techniques – by making the design process more accessible to ‘non-designers’

• building capacity, not dependency – by not only shaping a solution but leaving behind the tools, skills and capacity for ongoing change

• designing beyond traditional solutions – by applying design skills in non-traditional territories giving rise to the creation of new roles, new organizations, new systems and new policies, i.e. requiring a high level of ‘systems thinking’

• creating fundamental change – by aiming high and at transforming a national system or company’s culture.

Transformation design shares certain characteristics with PD and with metadesign (see below) in that it is about encouraging, shaping and catalysing rather than directing and controlling. It is open-ended, welcomes diversity and encourages a pro-am (professional-amateur) community of designers.

Metadesign

In the 1980s, the concept of metadesign, or meta-design, emerged with the use of information technologies in the practices of art, cultural theories and design. The expansion of networking information technologies, particularly the internet, led to a revival of interest in metadesign in the late 1990s and it is now an emergent design approach beyond that of user-centred and participatory design.57 According to Fischer, ‘Meta-design characterizes objective techniques and processes for creating new media and environments that allow the owners of problems to act as designers.’ The aim is to empower users to engage in ‘informed participation’58 –where participants from lay and professional backgrounds transcend beyond the acquisition of information to acquire ownership in problems and contribute to their solutions. Metadesign is particularly suited to dealing with complex problems and enabling knowledge sharing to encourage social creativity.59 Metadesign actually offers a process model for designing that sets up a conceptual framework of seeding followed by evolutionary growth and reseeding of the process model (SER Process Model).60 In this sense the designed environment for metadesign to take place is under-designed to create spaces for others to add their creativity and design, and to permit the system to evolve. This process contrasts with PD processes where there tends to be an end-point when the design outcome/solution is designed and can no longer be evolved by users.61 Metadesign is seen as co-creative and co-evolutionary, encouraging an ‘unselfconscious (or spontaneous) culture of design’.62

John Wood sees metadesign as a way to create beneficial affordances by offering a more holarchic, consensual and transdisciplinary approach – i.e. a superset of design.63 Metadesign teams would include entredonneurs (innovative altruists who broker new connections) and entrepreneurs (similar, but motivated by personal gain). Offering ten characteristics of metadesign, Wood believes this approach to be one of the few ways that (meta)designers might change the paradigm.64 In a colloquium on metadesign hosted by Attainable Utopias at Goldsmiths, University of London in June 2007, a wide range of contributors from the culture of design voiced their thoughts.65 Metadesign could:

• be a vision of ‘creative democracy’ (John Chris Jones)

• encourage autopoiesis (any organism – whether it be a social institution or a cellular life form – maintains its survival by self-balancing its self-identity with its external identity) and self-regulation (Otto van Nieuwenhuijze)

• facilitate an increase in virtually inexhaustible resources – ideas and happiness (Richard Douthwaite)

• encourage more self-reflexive, co-creative tasks and teams that regulate themselves (Rachel Cooper and Daniela Sangiorgi)

• raise the expectations of the ultimate potential of organizations and hence society (Ken Fairclough)

• inspire a new design approach in which participants work together in a social, cultural and ecological interdependence (Batel Dinur)

• create a society with a focus on the human-centred experience and new ‘qualities of life’ (Ian Grout)

• generate increased levels of synergy, i.e. better accord between different parts of the whole, where synergy is defined as the sharing of data, the sharing of information, integration of experience and skill in knowledge-sharing synergies, and the complex idea of wisdom-sharing synergies (John Wood)

• redefine designers to include not only the professionals, but also all participants in the extended designing network (Ezio Manzini).

A handbook of 21 metadesign tools to be published in 201066 will show real-world examples and offer a conceptual framework. In the meantime an outline of 21 metadesign tools is given in Appendix 3. It appears that metadesign offers an adaptive space for redirective practice to encourage designers to find innovative ways of addressing situations for the over-consumers and under-consumers.

Social design

All design is social, as design is the enactment of human instinct and a construct that facilitates the materialization of our world.67 The idea that design is instinctive is supported by Alexander’s notion of an unselfconscious culture of design where it is natural to fix or redesign something that results from a failure or inadequacy of form68 and given further credence by Herbert Simon’s observation that we all tend to design by changing existing situations into preferred ones.69 The term ‘social design’ has diverse meanings,70 but here it refers to the development of a social model of design,71 and a design process intended to contribute to improving human well-being and livelihood.72 While ‘the primary purpose of design for the market is creating products for sale … the foremost intent of social design is the satisfaction of human needs’.73 Social work theory (and practice) examines the interaction between client systems and environmental domains (Figure 5.4). Improvements in any of the environmental domains would generate an improved satisfaction of human needs. Social workers bring in additional professional support for the client system, as required, to the collaborative social worker–client space. Clients are then taken through a step-by-step process of problem solving involving engagement, assessment, planning, implementation, evaluation and termination (Figure 5.5). There are some obvious parallels between the social worker’s and designer’s roles in PD and the skill set required by a designer applying social design requires a deepened ability to listen and holistically explore the environment domains.

Figure 5.4

Interactions examined in social theory

The broad objective of social design is to improve ‘social quality’, defined by De Leonardis as ‘the measure of citizens’ capability of participating in the social and economic life of their community in conditions that improve both their individual wealth and the conditions of their community’.74 Morelli suggests that the identification of actors and their motivations, and the use of mapping tools used in social construction studies, is an essential step in realizing innovation at the local level.75 This also establishes how the existing context provides products and services that are intended to improve our well-being. In the project Sustainable Everyday, organized and coordinated by Milan Polytechnic, access to result-orientated networks in a particular context offer people a series of potential functionings (a set of solutions people have access to) and capability is defined as the possibility of a person achieving a satisfying result from these functionings.76 Here, designing new functionings to elevate individual and community capability, focuses the designer on the social dimensions of the outcomes but encourages the provision of enabling solutions, solutions that genuinely empower and extend the capability of the user. This strategy contrasts with the provision of yet more products and services, which can produce passive rather than active citizens. As the transition towards sustainability is seen as a social learning process,77 then the further development of a theory of social design seems an imperative. This is being recognized under new programmes such as the Utrecht Manifest,78 the emergence of a number of organizations collating and disseminating efforts in social design79 and educational programmes, such as The Good Life Project at Parsons School of Design, New York.80

Figure 5.5

Social workers’ generalist practice of problem solving

Co-design is expressed to varying degrees in other design approaches – some with an extensive history and well-developed methodologies (user-centred design, inclusive/universal design) and others that are emergent (user-innovation, mass collaboration, slow design).

User-centred design

The involvement of users, i.e. the end-users, of the design artefact, service or outcome, in the (professionally guided) design process presents a continuum from no involvement to some expression of co-design. User-centred design (UCD) can be applied at any stage in the design process and aims to interrogate the needs, wants and limitations of users in the design context. UCD emerged in the 1980s as a tool to assist in new product development (NPD) where particular user groups would be invited or selected to participate in focus groups commenting on certain stages in the design process, especially the testing of early concepts and prototypes.81 Gathering user-based intelligence through lead-user innovators and user-innovation was later introduced as a new UCD approach to assist NPD.82 This was in addition to information on users supplied by market research (again, often relying on focus groups) and was a means to get feedback on the emergent designs prior to committing further financial investment. UCD in the context of the design of software systems is a well-prescribed methodology and even has its own ISO standard for human-centred design processes for interactive systems.83 UCD often requires particular adaptations to fit the particular design discipline or is dovetailed to another design approach.84 Other user-research methods can extend UCD intelligence, such as ethnographic research and cultural probes.85 Today, the use of distributed networking technologies, especially the internet, is enabling a new evolution of UCD with more participatory methods involving user-innovation and even mass collaboration (see below).

Inclusive/universal design

The terms ‘inclusive’ and ‘universal’ are often interchangeable but imply that the intention of this kind of design approach is that no one is excluded from access or use of a design product, service or outcome.86 Inclusive design invites inclusion of all members of society, while universal design is readily accessible and usable by all members of society. Other terms are invoked, such as ‘design for all’, ‘transgenerational design’ and ‘barrier-free design’.87 Designing to be inclusive or universal aligns with contemporary political thought about an inclusive society, adopted by government, commercial and not-for-profit sectors.

As the proportion of elderly increases in many societies in the North, their exclusion from access to products, services and public places by poor design remains a problem. Making design more inclusive is part of being a responsible socially orientated designer. There are a wide range of techniques and methodologies to support inclusive design practice, some recently developed by the Helen Hamlyn Research Institute.88 The degree of participation required of the users, stakeholders and actors is under the direction of the designers relevant to the context in hand.

Mass collaboration and user-innovation design

A diverse and fluxing group of participatory design approaches, many poorly defined as yet, are associated with the emergence of Web 2.0 technologies, such as wikis, blogs, etc.89 which facilitate communication, discussion and collective working on distributed networks. The main thrust of these emergent mass collaboration and user-innovation approaches is that they tend to be driven from the internet community at large rather than from specific commercial or government organizations. The term ‘mass collaboration’ is defined as ‘a form of collective action that occurs when large numbers of people work independently on a single project, often modular in its nature’.90 The emergent phenomenon is seen as heralding a paradigm shift in how existing and future business will be conducted.91 Charles Leadbeater coined the term ‘we-think’, suggesting that current experiments in we-think are creating new possibilities for ‘we-make’,92 and suggests these new trends may also spread to the provision of public services. Mass collaboration is closely linked with other internet phenomena such as ‘smart mobs’ –a form of intelligent self-structuring social organization and coordination through technology-mediated networks and communication – a term coined by Rheingold,93 and ‘crowdsourcing’ – a form of PD enabled through distributed networks that is predominantly being tested by businesses to outsource certain services and skills.94

The societal and economic value of these forms of PD is yet to be fully realized, but the success of building content-based text resources, such as Wikipedia, or software, such as the Linux operating system and OS software, suggests these approaches will be tested further for their application to design projects. As one of the founders of Wikipedia, Jimmy Wales, has noted, its success is down to a mix of five constituents held in the kind of productive tension that traditional organizations may find difficult to adopt:

• one part anarchy (anything goes)

• one part democracy (people can vote on a disagreement)

• one part aristocracy (people who have been around for a long time get listened to)

• one part meritocracy (the best ideas win out), and

• one part monarchy (on rare occasions the buck has to stop somewhere).

This suggests that any designer entering such a process has to simultaneously respect the inherent design abilities of other participants while bringing their special design skills to bear.

Another emergent design approach is slow design, a term initially coined as a rhetorical query of the default ‘fast design’ paradigm with its uncontested and unsustainable flows of resources, and as a means of reframing eco- and sustainable design.95 Slow design requires stepping outside the existing mental construct of capitalism, where metabolism is driven entirely by economic imperatives, to consider other metabolisms and in doing so generate fresh awareness, possibilities and subsequently help create new societal values. Initial areas of focus posited for slow design included ritual, tradition, experiential, evolved, slowness, eco-efficiency, open-source knowledge and (slow) technology,96 and proposed some guiding principles, processes and outcomes (Appendix 4).

Slow design contributes to an emergent slow movement, inspired originally by the Italian organization, Slow Food, founded by Carlo Petrini in 1989,97 encompassing a diverse range of slow activists (Table 5.1). This reveals an increasing public consciousness about the positive impacts of slowness98 and a potential role for design in eliciting transition towards slower societal metabolisms.99 In 2006, SlowLab posited six principles of slow design100 as follows:

• Principle 1: Reveal: Slow design reveals experiences in everyday life that are often missed or forgotten, including the materials and processes that can be easily overlooked in an artefact’s existence or creation.

• Principle 2: Expand: Slow design considers the real and potential ‘expressions’ of artefacts and environments beyond their perceived functionalities, physical attributes and lifespans.

• Principle 3: Reflect: Slow design artefacts/environments/experiences induce contemplation and what SlowLab has coined ‘reflective consumption’.

Expressions of activism in a diverse ‘slow movement’

Type | Subtype | Examples |

| ‘Anti’-activists | Anti-globalization Anti-car culture Anti-consumerist | A diverse coalition of groups Reclaim the streets, critical mass Buy nothing day –Adbusters |

| Slow positivism | Slow localism Slow environmentalism Slow design | Slow Food, slow cities, Transition Towns The Sloth Club Slow, SlowLab |

| Green or eco-lifestyle | Organic food Consumerism Transportation Tourist | Soil Association Green Map, Global Eco-label Network (GEN) Sustrans, Human Powered Vehicle Association (HPVA) The International Ecotourism Society |

Source: Fuad-Luke (2007)101 | ||

Figure 5.6

Ideation of new concepts in a workshop by using the ‘slow design’ principles

• Principle 4: Engage: Slow design processes are ‘open source’ and collaborative, relying on sharing, co-operation and transparency of information so that designs may continue to evolve into the future.

• Principle 5: Participate: Slow design encourages users to become active participants in the design process, embracing ideas of conviviality and exchange to foster social accountability and enhance communities.

• Principle 6: Evolve: Slow design recognizes that richer experiences can emerge from the dynamic maturation of artefacts, environments and systems over time. Looking beyond the needs and circumstances of the present day, slow designs are (behavioural) change agents.

These principles can be used by individual designers as a guide to developing their practice and for collaborative, participatory workshops. The principles are useful for interrogating the sustainability prism and have potential to generate new products, product-services and business models as revealed in the Milkota local, organic, milk sales system, generated during a participatory slow design workshop (Figures 5.6 to 5.8). SlowLab reveals an eclectic output of work from ‘slow designers’ that indicates transformation in the way designers work and how they come together and participate with others to encourage social cohesion.102 Slow design’s full potential remains to be explored.

Figure 5.7

Concept design for a local, organic, cyclic milk system –‘Milkota’

Figure 5.8

‘Milkota’ – concept renders for a milk bottle and cooler system

1 Globalization is defined here as ‘the connecting of individuals, communities, companies, non-profits and governments within networks of economic, technical, socio-cultural and political functionality’.

2 Jencks, C. (1996) What is Post-Modernism?, Academy Editions, London.

3 Mau, B. with Leonard, J. and the Institute without Boundaries (2004) Massive Change, Phaidon, London.

4 Toffler, A. (1971) Future Shock, Pan Books, London, p12.

5 See Honoré C. (2004) In Praise of Slow, Orion Books, London; Petrini, C. (2007) Slow Food Nation: Why Our Food Should Be Good, Clean and Fair, Rizzoli, New York.

6 Wood, J. (2003) ‘The wisdom of nature = the nature of wisdom. Could design bring human society closer to an attainable form of utopia?’, paper presented at 5th European Design Academy conference, April, Barcelona.

7 Buchanan, R. (1995) ‘Wicked problems in design thinking’, in V. Margolin and R. Buchanan (eds) The Idea of Design, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, p14.

8 See several articles in Design Issues, vol 23.

9 Rith, C. and Dubberly, H. (2007) ‘Why Horst W. J. Rittel matters’, Design Issues, vol 23, no 2, p73.

10 Ibid.

11 Bonsiepe, G. (1997) ‘Design – the blind spot of theory, or, theory – the blind spot of design’, conference paper for a semi-public event at the Jan van Eyk Academy, Maastricht, April 1997.

12 Liz Sanders and G. K. van Patter in conversation, ‘Science in the making: Understanding generative research now!’, NextDesign Leadership Institute (NextD), 2004, http://practicalaction.org/?, accessed September 2008.

13 Margolin, V. and Margolin, S. (2002) ‘A “social model” of design: Issues of practice and research’, Design Issues, vol 18, no 4, pp24–30; Morelli, N. (2007) ‘Social innovation and new industrial contexts: Can designers “Industrialize” socially responsible solutions?’, Design Issues, vol 23, no 4, pp3–21.

14 Leadbeater, C. (2008) We Think: Mass Innovation, Not Mass Production, Profile Books, London.

15 Howard, J. (2004) ‘Toward participatory ecological design of technological systems’, Design Issues, vol 20, no 3, pp40–53.

16 Thackara, J. (2005) In the Bubble: Designing in a Complex World, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

17 Wikipedia (2008) ‘ARPANET’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARPANET

18 Wikipedia (2008) ‘World Wide Web’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_wide_web; Wikipedia (2008) ‘Tim Berners-Lee’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tim_Berners-Lee

19 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Open source definition’ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_source_definition

20 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Open source’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_source_content

21 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Linux’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LINUX

22 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Wikipedia’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia

23 Leadbeater (2008), op. cit. Note 14; Tapscott, D. and Williams, A. D. (2007) Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything, Atlantic Books, London.

24 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Open design’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_design

25 Designbreak, www.designbreak.org

26 Leadbeater (2008), op. cit. Note 14.

27 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Copyleft’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyleft

28 Wikipedia (2008) ‘GNU General Public License’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNU_General_Public_License; and the GNU Project, www.gnu.org

29 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Design Science License’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Design_Science_License

30 Creative Commons, www.creativecommons.org; Wikipedia (2008) ‘Creative Commons’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_Commons

31 Hardie, M. (2007) ‘Creative License Fetishism’, available at http://summit.keiin.org/node/308

32 Pasquinelli, M. (2008) ‘The ideology of free culture and the grammar of sabotage’, available at http://rekombinant.org/docs/Ideology-of-Free-Culture.pdf, NAi Publishers, Rotterdam.

33 See also Wikipedia (2008) ‘Copyfarleft’, http://p2pfoundation.net/Copyfarleft

34 Woodhouse, E. and Patton, J. W. (2004) ‘Design by society: Science and technology studies and the social shaping of design’, Design Issues, vol 20, no 3, pp1–12.

35 Bonsiepe, G. (2006) ‘Design and democracy’, Design Issues, vol 22, no 2, pp27–34.

36 Stairs, D. (2005) ‘Altruism as design methodology’, Design Issues, vol 21, no 2, pp3–12.

37 Whiteley, N. (2003) Design for Society, Reaktion Books, London.

38 See for example, Rocchi, S. (2005) ‘Enhancing sustainable innovation by design: An approach to the co-creation of economic, social and environmental value’, PhD thesis for Erasmus University, Centre for Environmental Studies, Rotterdam; Morelli (2007), op. cit. Note 13; Thackara (2005), op. cit. Note 16; Howard (2004), op. cit. Note 15.

39 Fuad-Luke, A. (2007) ‘Re-defining the purpose of (sustainable) design: Enter the design enablers, catalysts in co-design’, in J. Chapman and N. Gant (eds) Designers, Visionaries + Other Stories, Earthscan, London, pp18–52.

40 Carroll, J. M. (2006) ‘Dimensions of participation in Simon’s design’, Design Issues, vol 22, no 2, pp3–18.

41 Broadbent, J. (2003) ‘Generations in design methodology’, The Design Journal, vol 6, no 1, pp2–13.

42 Fuad-Luke (2007), op. cit. Note 39, pp37–47.

43 See for example, Transition Towns, www.transitiontowns.org/, described in Hopkins R (2008) The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience, Green Books, Totnes.

44 See for example, Bell, B. (2004) Good Deeds, Good Design: Community Service through Architecture, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

45 See for example, Wates, N. (ed) (2008) The Community Planning Event Manual, Earthscan, London.

46 See for example, Designs of the Time 07, Dott 07, www.dott07.com/, and described in Thackara, J. (2007) ‘Wouldn’t it be great if … we could live sustainably – by design?’, Dott 07 Manual, Dott 07 and Design Council, London; System Reload, www.systemreload.org/

47 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Direct democracy’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Direct_democracy; ‘anticipatory democracy’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anticipatory_democracy; and ‘deep democracy’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_democracy

48 Nieusma, D. (2004) ‘Alternative design scholarship: Working towards appropriate design’, Design Issues, vol 20, no 3, p16.

49 Illich, I. (1973) Tools for Conviviality, Harper & Row Publishers, New York.

50 Schuler, D. and Naimioka, A. (1993) Participatory Design: Principles and Practices, Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, New Jersey, pXI, quoted in Nieusma (2004), op. cit. Note 48, p16.

51 Faiola, A. (2007) ‘The design enterprise: Rethinking the HCI education paradigm’, Design Issues, vol 23, no 3, pp30–45.

52 Bell (2004), op. cit. Note 44; Wates (2008), op. cit. Note 45.

53 Carroll (2006), op. cit. Note 40.

54 Sanders (2002), op. cit. Note 12.

55 See for example the Italian design agency Experientia, and its blog, ‘Putting people first’, www.experientia.com/blog/

56 Burns, C, Cottam, H., Vanstone, C. and Winhall, J. (2006) RED Paper 02 Transformation Design, Design Council, London.

57 Fischer, G. (2003) ‘Meta-design: Beyond user-centered and participatory design’, available at http://13d.cs.colorado.edu/~gerhard/papes/hci2003-meta-design.pdf

58 Brown, J. S. and Duguid, P. (2000) The Social Life of Information, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, cited in Fischer (2003), op. cit. Note 57.

59 Arias, E. G., Eden, H., Fischer, G., Gorman, A. and Scharff, E. (2000) ‘Transcending the individual human mind – creating shared understanding through collaborative design’, ACM Transactions on Computer Human Interaction, vol 7, no 1, pp84–113, cited in Fischer (2003), op. cit. Note 57.

60 Fischer, G. and Oswald, J. (2002) ‘Seeding, evolutionary growth, and reseeding: Enriching participatory design with informed participation’, Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference (PDC’02), Malmö University, Sweden, pp135–143, cited in Fischer (2003), op. cit. Note 57.

61 Giaccardi, E. and Fischer, G. (2005) ‘Creativity and evolution: A metadesign perspective’, in Sixth International Conference of the European Academy of Design (EAD06) on Design>System>Evolution, Bremen, University of the Arts, March.

62 Alexander, C. (1964) The Synthesis of Form, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, cited in Giaccardi and Fischer (2005), op. cit. Note 61.

63 See John Wood in the June 2007 colloquium, ‘The Idea of Metadesign, Attainable Utopias’, http://attainable-utopias.org/tiki/tiki-index.php?page=MetadesignColloquiumOverview

64 Wood, J. (2008) ‘Changing the change: A fractal framework for metadesign’, a paper presented at Changing the Change conference, Turin, July, available at www.allemandi.com/cp/ctc/book.php?id=129

65 See the various contributors in the June 2007 colloquium, ‘The Idea of Metadesign, Attainable Utopias’, http://attainable-utopias.org/tiki/tiki-index.php?page=MetadesignColloquiumOverview

66 Wood, J. (forthcoming) 21 Metadesign Tools for the 21st Century.

67 See forexample, Papanek, V. (1971) Design for the Real World, Paladin, St Albans; Papanek, V. (1995) The Green Imperative, Thames & Hudson, London; Neutra, R. (1954) Survival through Design, Oxford University Press, Oxford, p314.

68 Alexander (1964), op. cit. Note 62.

69 Simon, H. (1996) Sciences of the Artificial, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, originally published 1969.

70 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Social design’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_design

71 Margolin and Margolin (2002), op. cit. Note 13.

72 Holm, I. (2006) Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial Design: How Attitudes, Orientations and Underlying Assumptions Shape the Built Environment, Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Oslo.

73 Margolin and Margolin (2002), op. cit. Note 13, p25.

74 De Leonardis cited in Morelli (2007), op. cit. Note 13.

75 Morelli (2007), op. cit. Note 13, p11.

76 Manzini, E. and F. Jégou (2003) Sustainable Everyday: Scenarios of Urban Life, Edizioni Ambiente, Milan; Sustainable Everyday website 2003–2008, www.sustainable-everyday.net/SEPhome/home.html#scenarios

77 Manzini and Jégou (2003), op. cit. Note 76, p45.

78 Utrecht Manifest, www.utrechtmanifest.nl/en/

79 For example, Social Design Site, www.socialdesignsite.com/ and Design 21, the Social Design Network in partnership with UNESCO, www.design21sdn.com/

80 Kirkbride, R. (2008) ‘Proposals for a good life: Senior thesis projects from Parsons Product Design 2003–2008’, a paper presented at Changing the Change conference, Turin, July, www.changingthechange.org, paper available at www.allemandi.com/cp/ctc/book.php?id=59

81 See for example, Norman, D. A. (1988) The Design of Everyday Things, Basic Books, New York.

82 von Hippel, E. (2005) Democratising Innovation, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

83 International Organization for Standardization (1999) ISO 13407 model.

84 For example, inclusive design through ‘critical user forums’, Dong, H., Clarkson, P. J., Cassim, J. and Keates, S. (2005) ‘Critical user forums – An effective user research method for inclusive design’, The Design Journal, vol 8, no 2 pp49–59.

85 Gaver, W., Dunne, A., and Pascenti, E. (1999) ‘Cultural probes’, Interactions, vol vi, no 1, pp21–29; Gaver, W., Boucher, A., Pennington, S. and Walker, B. (2004) ‘Cultural probes and the value of uncertainty’, Interactions, vol XL5, pp53–56.

86 See for example, inclusive design – Clarkson, P.J., Coleman, R., Keates, S. and Lebbon, C. (eds) (2003) Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole Population, Springer-Verlag, London; universal design – Preiser, W. E. F. and Ostroff, E. (eds) (2001) Universal Design Handbook, McGraw-Hill, New York.

87 Dong et al (2005), op. cit. Note 84.

88 See for example, Helen Hamlyn Research Institute, www.hhc.rca.ac.uk/archive/hhrc/resources/index.html; Clarkson et al (2003), op. cit. Note 86; Keates, S. and Clarkson, P. J. (2003) Countering Design Exclusion: An Introduction to Inclusive Design, Springer, London.

89 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Web 2.0’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0

90 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Mass collaboration’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_collaboration

91 Tapscott and Williams (2007), op. cit. Note 23; Leadbeater (2008), op. cit. Note 14.

92 Ibid. Leadbeater (2008), pp133–141.

93 Rheingold, H. (2002) Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution, Perseus Books, New York.

94 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Crowdsourcing’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crowdsourcing

95 Fuad-Luke, A. (2002) ‘“Slow design” – a paradigm shift in design philosophy?’, a paper presented at Development by Design, Bangalore, India, November 2002.

96 Fuad-Luke, A. (2004) ‘Slow design: A paradigm for living sustainably’, available at Slow, www.slowdesign.org

97 Slow Food, www.slowfood.com/

98 Honoré, C. (2004) In Praise of Slow, Orion Books, London; also see SlowPlanet, www.slowplanet.com

99 ‘Slow + design: Slow approach to distributed economy and sustainable sensoriality’, international seminar, Milan, 6 October 2006, www.agranelli.net/DIR_rassegna/convegno_Slow+Design.pdf, accessed 17 January 2008.

100 Fuad-Luke, A. (2008) ‘Slow design’, in Erlhoff, M. and Marshall, T. (eds) Design Dictionary: Perspectives on Design Terminology, Birkhäuser-Verlag, Basel/Boston/Berlin, pp361–363; Strauss, C. and Fuad-Luke, A. (2008) ‘The slow design principles: A new interrogative and reflexive tool for design research and practice’, a paper presented at Changing the Change conference, Turin, July, www.changingthechange.org, available at www.allemandi.com/cp/ctc/book .php?id=109

101 Fuad-Luke, A. (2007) ‘Reflection, consciousness, progress: Creatively slow designing the present’, http://imaging.dundee.ac.uk/reflections/pdfs/AlastairFuad-Luke.pdf, accessed September 2008. A keynote presentation made at the conference Reflections on Creativity: Exploring the Role of Theory in Creative Practice, University of Dundee, April 2006, published 2007.

102 SlowLab, www.slowlab.net