Scoping the Territory:

Design, Activism and

Sustainability

‘Sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul.’

Edward Abbey, environmental author

‘Design, never a harmless play with forms and colors, changes outer life as well as our inner balances.’

Richard Neutra1

‘Design activism’ has a delicious tension. We carry an understanding of ‘design’ and of ‘activism’ but joining the words together imbues a certain ambiguity. To say ‘design activism’ is to imply that it already exists and has an established philosophy, pedagogy and ontology, i.e. it circumscribes a system of principles, elicits a wisdom and knowledge, has a way of teaching and has its own way of being. This may be an ambitious claim. Defining design activism and its effects has the potential to result in a pluralist, messy and contestable result. However, this book hopefully gives some credence to the existence of an emergent design activism and its healthy potential to help us deal with important contemporaneous societal issues.

Defining ‘Design’ Today

‘Design’ and ‘activism’ are words carrying a similar burden. They are conjured in the mind and transport our thinking in diverse ways; they are malleable, easily borrowed and corruptible. A recent discourse about design terminology2 provides an insight into the complex world of design today by citing a wide variety of adjectives or nouns as a prefix or suffix to ‘design’ (Table 1.1). This terminology refers variously to the type of design author, the design context or discipline, the design approach, historical design precedents, and an arena for practising design. Moreover, the editors find it ‘impossible to offer a single and authoritative definition of … design’.3 Flexible verbal accounts of ‘design’ reveal that design is tied to cultural perceptions that are contemporary and yet very personal.4 It seems that design is difficult to pin down and is everywhere. Indeed, a glance at the long list of design disciplines reveals that design has penetrated every facet of our materialized and virtual worlds (Figure 1.1). Design also embodies diverse historical and contemporary styles, invokes a wide range of disciplines, has legal protection (registered designs and intellectual property, IP) and is practised by professionals (of varying public status from unknown to known, but not yet famous), iconic or avant-garde designers (famous, auteur or signature designers) or by anonymous or non-intentional designers.

Prefixes and suffixes associated with the word ‘design’

Prefixes – anonymous, architectural, audiovisual, auteur, automobile, Bel, broadcast, character (films, comics, games), collaborative, conceptual, corporate, critical, cross-cultural, digital, eco, engineering, environmental, event, exhibition, fashion, food, furniture, futuristic (futurism, streamline design), game, gender, good, graphic, green, industrial, information, interaction, interface, interior, jewellery, landscape, lighting, mechatronic, media, non-intentional, olfactory (scent), packaging, participatory, photographic, poster, product, protest, public, radical, re-, registered, retail, retro, safety, screen, service, set, shop, signature, slow, sound, stage, strategic, streamline, textile, time-based (animation, performance), title (film credits), transportation, TV, universal, urban, web

Suffixes – criticism, education, history, management, planning, research, theory

Source: Erlhoff and Marshall (2008)5

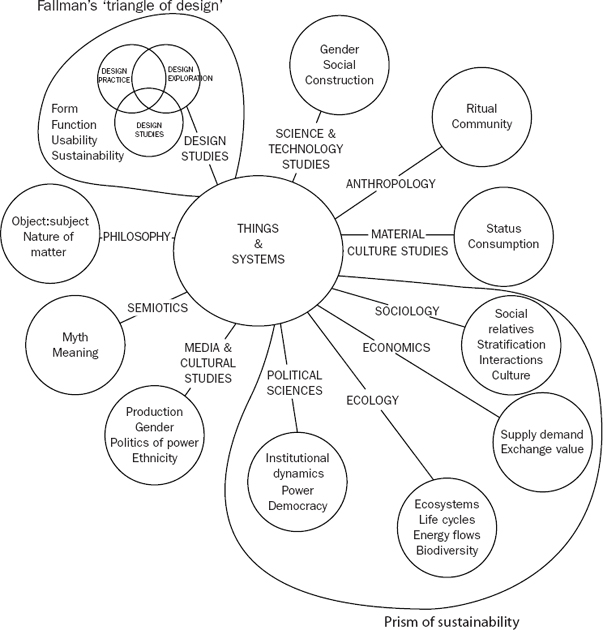

Design crosses a diverse range of subject fields and disciplinary borders (Figure 1.2) giving design a unique reach among the creative disciplines, while simultaneously adding more complexity and blurring the discursive space. Figure 1.2 combines the work of Prasad Boradkar, who suggests that design operates on things and systems,6 and D. Fallman, who sees design in dynamic tension between design practice, design studies and design explorations.7 A further layer of complexity is added to the designing of ‘things and systems’ by considering the four sustainability dimensions – economic, ecological, social and institutional – proposed by Joachim Spangenberg.8 Design also embraces myths and meaning, philosophy, science, teaching/education, anthropology, sociology, material culture studies, media and cultural studies, economics, political sciences, economics and ecology. It is design’s ability to operate through ‘things’ and ‘systems’ that makes it particularly suitable for dealing with contemporary societal, economic and environmental issues.

Design, therefore, is manifest in all facets of contemporary life. Design is executed by designers that are trained, professional and offer expertise. Yet it is also engaged by designers that are unknown (anonymous, non-intentional) and who gain their expertise from outside the design professionals’ world. This dualism would seem to be equally apt for ‘activism’. There are well-known activists who have a public profile and earn their living as professional activists9 and there are also many unknown activists beavering away out of the public gaze. The nature of contemporary ‘activism’ is elaborated on below, but a definition of design that embraces this professional/non-professional dualism can be found in two seminal works published in the late 1960s/early 1970s. In 1969, Herbert Simon10 noted:

Design descriptors

Design in relation to other disciplinary studies focusing on ‘things and systems’

‘Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations, into preferred ones.’

And in his polemical book, Design for the Real World, Victor Papanek11 opened with the words:

‘All men are designers. All that we do, almost all the time, is design, for design is basic to all human activity.’

Papanek’s views still receive considerable debate, both positive and negative,12 as some designers draw very clear boundary lines between the work they do as professionals and the kind of design executed by other professionals or laypeople. Those who practice design activism tend to blur these boundaries considerably.

Both Simon and Papanek are frequently cited by those keen to stress the important contribution that design does and can make to contemporary issues affecting societal development and environmental stability.13 Simon’s all-encompassing definition of design seems most fitting to the territory of design activism because activists can originate from a spectrum of status, from activist professionals to unknown activists. A working definition of design is therefore proposed:

Design is the act of deliberately moving from an existing situation to a preferred one by professional designers or others applying design knowingly or unknowingly.

Defining ‘Activism’ Today

‘Activism’ is a broad church. As our industrial economies and concurrent societies have metamorphosed into ‘post-industrial’, ‘consumer’ and ‘knowledge’ economies, expressions of activism have taken on more pluralistic forms, aided and abetted by information communication and technology (ICT) platforms, especially the internet.14 Activists, that is those carrying out the activism, can belong to social, environmental or political movements that are localized or distributed, and that are based upon collective and/or individual actions. They are often allied to, or are, the founders of social movements, defined by Tarrow15 as:

‘Collective challenges [to elites, authorities, other groups or cultural codes] by people with common purposes and solidarity in sustained interactions with elites, opponents and authorities.’

Other activists orientate around special interest groups gathered around specific issues with an anthropocentric focus (e.g. AIDS, pro-life anti-abortionists, anti-war, fathers’ rights, feminism, anti-poverty) whereas others take a more biocentric focus (e.g. animal rights, environmentalists, anti-nuclear power).16 The professional activism industry is dominated by not-for-profit, charitable and non-governmental organizations working across the political, social, environmental, institutional and economic agendas. Lobbyists working on behalf of corporations and political parties also have an activist role in influencing these agendas.

All activists are involved in inculcating change that favours their ‘world-view’, i.e. how they see the current paradigm(s) and the associated issues. Change implies moving from ‘state A’ of a system to ‘state B’. This may involve a transformation of the system and its target audiences or social groups, but often also involves the transformation of the individual activists too. Both these notions of transformation can be embedded in a working definition of activism:

Activism is about … taking actions to catalyse, encourage or bring about change, in order to elicit social, cultural and/or political transformations. It can also involve transformation of the individual activists.

As such, activism operates on social, cultural and political capital to elicit a change to the stock by catalysing new flows of stock. This construct of ‘capital’, ‘stock’ and ‘flow’ offers a potentially useful way of viewing the potential and real effectiveness of activism.

Activism and the Five Capitals Framework

Activism operates on a variety of forms of capital that contribute in different ways, and by different means, to the globally shared notion of ‘capitalism’ which has come to dominate economic and political thinking. The Forum for the Future’s Five Capitals Framework17 is posited here as a means of examining where activism aims to exert an effect on different capitals. The five capitals are natural, human, social, manufactured and financial (Table 1.2). Natural capital is the capital that underwrites every other form of capital since it is the capital from which all life springs. Human capital is held in each individual human and is therefore another primary capital. Social, manufactured and financial capitals are derived from the two primary forms of capital – natural and human. There are three other forms of capital – man-made (material) goods, cultural and symbolic capitals – which are also important to consider beyond the Five Capitals Framework as design plays a particularly important role in regulating their flow (see Figure 1.3). Design mediates, to some extent, the flow of all these capitals. So it is important to understand the diversity and complexity of contemporary activism, so the designer can locate areas for activist work in a larger landscape.

Activism affects the perception and quality of stock of these capitals, especially those capitals that are socially orientated – social, cultural, human, institutional – around which societal and ‘political’ change pivots. Political in this sense is not a narrow view of political parties and their respective philosophies and beliefs, but is a wider view of the citizen contributing to a broad political dialogue within society, where the question being asked is ‘in what sort of society do we want to live?’.18 Design is implicitly embedded in this question and so all design can be considered political.

The Five Capitals model and other capitals

Capital |

Description |

The Five Capitals | |

| Natural (environmental, ecological) | ‘Any stock or flow of energy and matter [from the natural world] that yields valuable goods and services.’ Resources – renewable, e.g. timber, grain, fish, and non-renewable, e.g. fossil fuel; sinks – absorb, neutralize or recycle waste; services, e.g. climate regulation by air, cloud, wind.19 Resources are the main measured stock and it is our difficulty or unwillingness to measure and/or value other natural capital stocks that makes the capital in the larger ‘environment’ at risk from over-exploitation. |

| Human | Adam Smith defined human capital in his 1776 economic treatise, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, as ‘the acquired and useful abilities of all the inhabitants or members of the society’.20 He indicated that each person acquired this human capital during his/her education, study or apprenticeship; that acquisition had a real cost; and that human capital resides within the person. Physical, intellectual and psychological skills and dexterity, and judgement, are all forms of human capital. Forum for the Future expands this list to embrace spiritual and emotional capacities.21 While Smith was largely thinking about how human capital contributed to improvements in financial, manufactured and natural capital held in land, more modern definitions see human capital as something each one of us brings to any work, play, nurturing or loving situation, i.e. today we have a much more holistic view. |

| Social | Social capital holds a wide variety of meanings (Wikipedia, social capital)22 but most agree that it concerns connections between and within social networks that encourage civic engagement, engender trust, create mutual support, establish norms, contribute to communal health, cement shared interests, facilitate individual or collective action, and generate reciprocity between individuals and between individuals and a community. Bridging social capital is inclusive23 as it is outward looking and tries to join people from different social units or groups, e.g. the civil rights movement. In contrast, bonding social capital is exclusive as it looks within the social unit or group to reinforce an identity, e.g. a church group, social club or urban gang. Not all social capital is therefore positive as some forms of social capital divide societies while other forms strengthen societies. Social capital is represented by two important subsets – institutional capital and cultural capital – that have considerable influence on whether social capital is used to deliver positive growth or negative impacts on the whole or parts of societies. |

| Financial | Financial, or economic, capital is represented by money and other financial instruments which in themselves are merely a representation of other forms of wealth (capital) equating to one or all of the following: a medium of exchange; a standard of deferred payment; a unit of account; or a ‘symbolic’ store of value.24 Porritt argues that financial capital is governed by markets and institutions that are, in effect, social networks with stocks of specialist information and expertise, and that transactions take place based on norms and trust.25 |

| Manufactured | Manufactured capital is man–made material artefacts that ‘contribute to the production process, but do not become embodied in the output of that process’.26 This includes buildings, infrastructure and technologies. Buildings include the built environment of villages, towns and cities; infrastructure is the physical fabric that society depends upon including systems for transportation, education, health, energy, water and waste disposal; technologies include tools, machines, information technology (IT), biotechnology and engineering that enable the production of goods and services. Infrastructure is sometimes referred to as infrastructural capital, and is held in public, public/private or private ownership for the purpose of the common good. |

‘Other’ capitals | |

| Man–made (material) goods | Man–made goods originate because natural capital is converted by manufactured capital using social, financial and human capital. This form of capital is at the heart of the ‘consumer economy’ that emerged in the 1930s in the US and found momentum worldwide in the 1950s, and finally evolved into the ‘global economy’ in the 1990s. This type of capital is introduced here because it is the primary capital with which design works and is implicit in the debate around sustainable consumption and production (SCP), a concept that tries to balance stock and flow of natural capital with other capitals and with an increasing world population that continues to put yet more demand on depleting stocks. SCP is really asking how many man-made goods natural capital can support, now and in the long term. |

| Cultural | Cultural capital first emerged as a sociological concept in the early 1970s27 and was later developed by Bourdieu28 to indicate three manifestations: An embodied state where cultural capital is held in the individual as a culturally inherited and acquired set of properties that confers a certain social relation within a system of (social) exchange – this is part of human capital but requires social capital for its verification. An objectified state where individuals that possess more cultural capital have acquired material and symbolic goods that are deemed rare or worthy by society – these goods have both financial and symbolic capital and are derived from man-made goods capital. An institutionalized state recognizing the cultural capital conferred by institutions on individuals, such as an academic qualification, that enables the individual to achieve certain financial value in the marketplace – so this form of cultural capital is bound up in particular forms of social capital. As individuals move around society and are exposed to different forms of social capital, the currency of their cultural capital shifts. Certain states of cultural capital will have high value in certain social units or networks, whereas other forms of cultural capital will be perceived as having little or no value. Such value decisions are qualitative. |

| Capital | Capital is symbolically represented in all forms of anthropocentric capital – financial, manufactured, man-made goods, social, cultural and human capitals – because it forms the basis by which we recognize the sociological or anthropological status of individuals in society or within social units or groups. Symbols confer meaning and value, and therefore status. Those meanings and values are both collectively and personally held and negotiated, so will shift within and between different societies and cultures, and over time. |

Anthropocentric views of ten key ‘capitals’

All the above capitals can be affected in either a positive or negative way, depending on the aim or objective of the activism. So capital can be grown or diminished and/or redistributed differently. Figure 1.3 shows how the various capitals relate to each other, in particular how financial (economic) capital works across all the other forms of capital because money and other financial instruments are merely a representation of other forms of wealth (capital) equating to a medium of exchange, standard of deferred payment, unit of account or a ‘symbolic’ store of value.29 Physical capital embraces manufactured, infrastructure and material goods. In the Five Capitals model, ‘manufactured capital’ is man-made material artefacts that ‘contribute to the production process, but do not become embodied in the output of that process’.30 This includes buildings, infrastructure and technologies. Social capital embraces both human capital and the capital of humans gathered in institutions, and interfaces with ideas of cultural capital and symbolic capital.

Recent interpretations of human capital have included physical, intellectual, emotional and spiritual capacities.31 Danah Zohar indicates that the notion of ‘spiritual capital’ goes beyond any religious or institutionalized vision of ‘spirituality’, rather it addresses fundamental searches for ‘shared meanings, value and ultimate purpose’ and that this is critical if we are to achieve ‘sustainable capitalism and a sustainable society’.32 Forms of activism are also an attempt to disrupt existing paradigms of shared meaning, values and purpose to replace them with new ones, and so activism perhaps embodies a sense of developing the spiritual capacity of individual human capital, that is collectivized in social capital.

The activism landscape

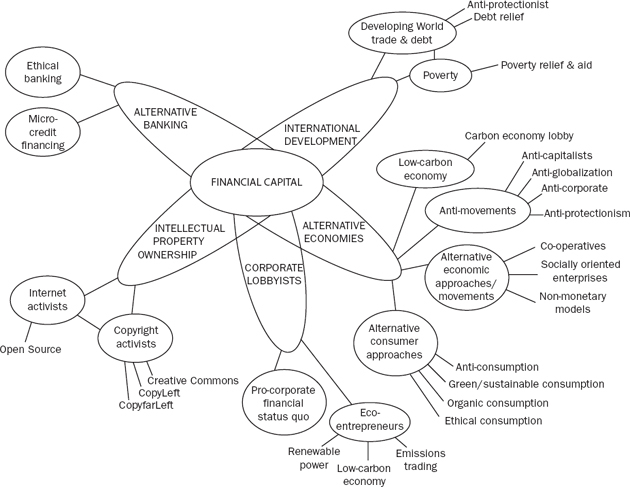

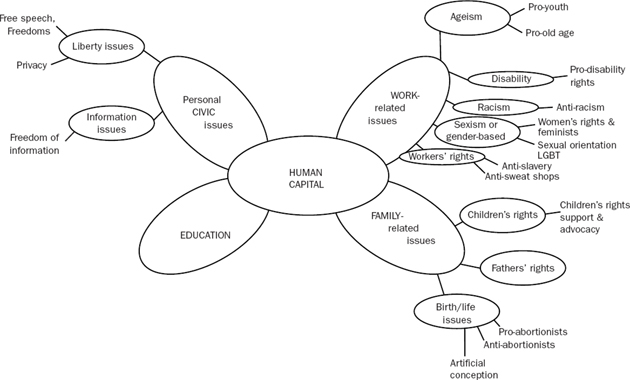

It is possible to construct a map of contemporary activism focal points and issues by referring to the Five Capitals Framework (Figures 1.4 to 1.8) and by also considering the capital of man-made (material) goods (Figure 1.9). These ‘mind-maps’ are conceived as a starting point for the reader to extend or modify this activist landscape, rather than a definitive mapping. Certain focal points or issues are common to the maps for several capitals. For example, alternative economic approaches such as co-operatives, social enterprises and non-monetary models feature in financial capital and man-made (material) goods capital. The concept of ‘low-carbon economy’ features in financial capital and in natural capital.

There are five key areas of activism centred around financial (economic) capital (Figure 1.4):

• international development

• alternative economies

• corporate lobbyists

• intellectual property ownership

• alternative banking.

Activism around financial capital

Activism around natural capital

Activism around human capital

Activism around manufactured capital

Activism around social capital

Activism around man-made goods capital

Natural capital distinguishes between the approaches of the ‘deep’ and ‘shallow’ ecologists, environmentalists, alternative consumption movements and those concerned with the security of natural resources in national territories (Figure 1.5). The foci of activism around human capital are based around rights and issues concerned with work, family, education and personal civic rights and issues (Figure 1.6). Manufactured capital is centred around buildings, infrastructure and technologies (Figure 1.7). The focal points and issues around social capital are the most numerous and complex but orientate around three main areas – social/civic, political and religious domains (Figure 1.8). Lastly, the activism associated with man-made (material) goods capital is orientated around the life cycle of production, consumption and end-of-life, and how these material goods are communicated through diverse media channels (Figure 1.9).

Reference to this schematic model reveals an activism landscape that is varied and far ranging. While many of the focal areas of activists are clearly anthropocentric, and gather around changing social, cultural and/or political thinking, structures and activities, other activists address biocentric causes including representation to support ‘endangered species’ and biodiversity, animals and their rights, and the conservation or restoration of specific habitats. The scope for the design activist to contribute to this activism landscape is huge. The areas where design activists are already contributing is discussed in later chapters.

Activism in architecture, design and art

In a broader design context there is a strong emergent interest in how design is engaging with issues both locally and globally.33 This is explored further in Chapter 4. However, there is a paucity of literature addressing the notion of activism in many of the design disciplines (which this book sets out to address), with the exception of architecture and graphic design which have received more attention regarding the nature of their activism. The literature ranges from examining the thoughts and outputs of individual architects or graphic designers to looking at broad trends and approaches. For example, Whyte examines in minute detail the work of the German architect Bruno Taut and the ‘Activists’, emerging out of Expressionism into Functionalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.34 In reality the Activists, informed by ‘social idealism’, had little effect on inculcating real social change as its proponents remained aloof architectural visionaries rather than grassroots political revolutionaries. Dovey explored the nature of power structures mediating the built environment and the architecture activism deployed in this mediation process.35 Farmer examined the green/ecological timeline through architectural design history.36 More recently, several works have examined architectural practice in the improvement of lives for the poor and displaced in the US, the developed North and the developing South.37,38 There is a rich seam of texts that look at all facets of the ecological, bioclimatic and environmental dimensions of architecture39 – all relevant topics for the architect activist wishing to tread more lightly on the planet’s resources.

Graphic design, firmly rooted in the arena of design communication, has long been associated with social and political discourse and propaganda. Recent studies indicate a rude health for graphic design activism from the early struggles of the suffragette movement in the 1860s to the present day.40 The voices of graphic designers regularly bubble up during times of social and political change, both in the service of clients’ needs and with concerns raised by the designers themselves, the latter being good examples of design-led activism.41 Showing a continued thirst for responsible graphic design, the First Things First manifesto launched by Ken Garland in 1964 was recently republished by self-proclaimed ‘culture jammers’ Adbusters in 1999,42 who have their own particular brand of graphic design activism particularly targeting transnational corporations.43 This is an indication that graphic design still has a very central role to play in activism’s wider purpose.

While the subject of this book is design, a brief consideration of art’s relationship with activism is helpful at this juncture. Although art would seem to occupy a prime position to influence social and political discourse, Felshin queries the uneasy relationship that ‘art activism’ has with ‘art’.44 The notion that art activism is challenging the culture of art and a wider socio-cultural platform is realized in the conceptual art of the late 1960s and early 1970s45 with its temporal, often performance-based interventions or activities, and its interventions in mainstream media. The approach of many of the artists in this era involved collaborative participation between other artists and a wider public, making the outputs only achievable with a dialogic exchange. In doing so they contested the notion of the art object and its ‘commodity-driven delivery system’ and led to new meaning for the art work being located in its contextual framework not in an autonomous object.46 This meant that new physical, institutional, social or other contexts could become the focus of an art work and, arguably, led to the emergence of the early environmental and land art from the likes of Robert Smithson and George Trakas. Lessons from this earlier art activism offer some insights into where commodity-driven design may care to set its ambitions (see Chapters 5, 6 and 7) including new arenas for participation.

Motivation and Intention

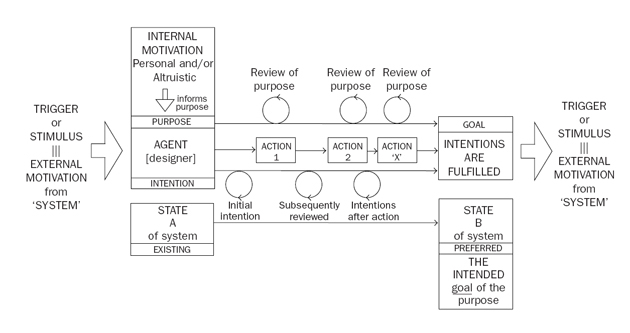

What motivates the activist? Personal motivation may embrace needs, desires, goals, a certain philosophical approach, or other intrinsic factors. Activists can mot also be driven by a strong sense of altruism or morality, aimed at delivering benefits for the greater societal good (although there may not be a consensus on what this ‘good’ constitutes). Aside from these intrinsic factors, external circumstances can provide strong motivational forces. A trigger or stimulus from the existing system can motivate. Activists tend to gather around social movements, interest groups around specific causes, a set of beliefs or perceptions that something is unjust, dangerous or of concern to future generations. Of great importance is how the activists frame their beliefs/perceptions as this contributes to defining their purpose or goal-orientation and hence their intention achieved through specific actions to reach the goal (Figure 1.10). Intention informs a series of iterative actions that continually allow interrogation of the purpose in order to reach the goal. The achievement of the goal is attainment of the original purpose. However, the effectiveness of the intention and purpose needs to be measured against the change in system from ‘state A’, the original state, to ‘state B’, the altered state.

A schematic of intention and motivation

While activists take on the role of ‘change agents’, trying to influence and change the behaviour of others, they may also experience what is known as ‘transformational activism’, a concept where the activists and the subject(s) of their activism undergo a personal internal transformation as well as expressing it outwardly. This suggests that being an activist is part of a personal developmental and life journey to realize a state of being, as well as a desire to contribute to a greater societal good.

As will be seen in later chapters, those who apply design in an activist cause need to have a clear idea of their purpose or intention and its potential effectiveness. This is particularly important when considering the targets of the activism and the intended beneficiaries.

Issue-Led Design and the Sustainability Challenge

The list of adjectives used as descriptors for design (Table 1.1) have been rearranged to reveal certain orientations (Figure 1.1): two major orientations emerge. It is clear that ‘design’ can be orientated towards a specific discipline and that certain approaches/frameworks can be applied. Particular considerations will be associated with specific design disciplines. So, for example, automobile design frequently deals with safety, ergonomics, aesthetics and fuel efficiency; fashion design has to consider drapability and durability of fabrics, colour trends, etc. Certain considerations apply across all disciplines, such as cost, availability of materials, clients’ needs and so on. What is interesting is that the design approaches/frameworks can, in general, be applied to any discipline. Furthermore, each design approach/framework embeds its own characteristics related to particular contemporary issues (Table 1.3). In other words, many design approaches/frameworks are already ‘issue-led’. In that sense design is already ‘activated’ in trying to address contemporary issues. Is there a meta-challenge, an overarching challenge, tying this seemingly disparate lexicon of design approaches/frameworks together? ‘Sustainability’ may be conceived as that meta-challenge – a concept that had its first tentative expressions more than 60 years ago, although it was then referred to in terms of man and his total environment.47

Characteristics and contemporary issues associated with particular design approaches/frameworks

Sustainability is grounded in ecological praxis and systems thinking. It challenges the capitalist system of production and consumption that assumes unlimited growth.

The concept of sustainability gathered renewed interest in 1980 when the term ‘sustainable development’ was first articulated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources48 with the most cited definition being quoted from Gro Harlem Brundtland’s 1987 report, Our Common Future:49

Sustainable development is ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs’.

Since then, substantive efforts have been made to agree on what sustainable development actually means, but it remains a ‘contestable concept like liberty or justice’.50 Sustainability has many flexible definitions, depending on the context and the field of study. Deeply rooted in the concept of sustainability is the question of equity, between and within generations51 and, the deep ecologists would argue, for an equity between humans and other life forms. Environmental economists, who by definition are engaged with improving ecological efficiency (improved economic viability with reduced negative environmental impact) tend to address sustainability by the maintenance or non-depletion of the Earth’s ‘natural capital’, i.e. all that nature’s biotic (living) and abiotic systems provide to man-made systems of capital. Yet this ignores the social and institutional dimensions of sustainability that strive to deliver equal shares of these capitals. Simon Dresner notes that ‘sustainability is an idea with a certain amount in common with socialism’.52 This socialist orientation ensures that many activists, of diverse persuasions well beyond the environmentalists, are attracted to the concept of sustainability.

There are dozens of definitions of sustainability, the most apt from a design point of view being the one adopted by Domenski et al in 1992 to reference the idea of the ‘sustainable city’, which is a complex design outcome:

‘Sustainability may be defined as a dynamic balance among three mutually interdependent elements: (1) protection and enhancement of natural ecosystems and resources; (2) economic productivity; and (3) provision of social infrastructure such as jobs, housing, education, medical care and cultural opportunities.’53

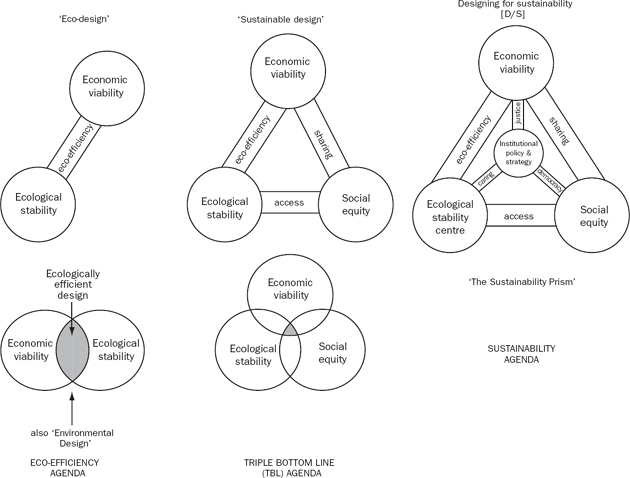

Designers of all persuasions may recognize the daily balancing act that they already carry out which acknowledges the mutual interdependence of the three elements. This definition recognizes the services that nature provides and the duty of care man has to nature, invokes productivity rather than economic growth, and links sustainability to our overall social condition and health. In fact these three elements, the ecological, the economic and the social are often used in Venn diagrams to represent eco-design and sustainable design with their eco-efficiency and triple bottom line (TBL) agendas – people, planet and profit (Figure 1.11). In 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development organized the Earth Summit bringing together nearly 200 nations to discuss the (perilous) state of the world’s environment.54 The Agenda 21 framework of action, emerging from the Earth Summit, added important considerations to the sustainability debate – the idea about participation, open government and institutional roles. The institutional element adds a level of complexity and gave rise to the sustainability prism (Figure 1.11) which links the ecological, economic, social and institutional dimensions.55 Moving from the bilateral agenda of eco-efficiency to the tripartite agenda of TBL shifts the number of possible relationships from one to three. Inclusion of the fourth institutional dimension suddenly generates six possible relationships, and so a level of complexity. Nonetheless, the sustainability prism becomes a more holistic framework for balancing considerations of the different dimensions and revealing opportunities and threats.

Sustainability is seen as the pre-eminent challenge of the 21st century, although it remains a quixotic and contentious concept. As a result, Janis Birkeland now prefers to talk about ‘positive’ rather than ‘sustainable’ development in the context of urban planning and design:56

‘Positive development refers to physical development that achieves net positive impacts during its life cycle over pre-development conditions by increasing economic, social and ecological capital.’

This definition specifies the direction of the development and how it should affect economic, social and ecological capital. Design can have a positive impact on these capitals and has already evolved over the past three decades to rise to the sustainability challenge. The question is how much of this design response can be considered as ‘design activism’?

Defining the Design Activism Space

An understanding of the wider activism landscape, as illustrated in Figures 1.4–1.9, reveals a broad territory for designers to consider where, when and how they can contribute to socio-cultural and political change, and in doing so help build positive capital in each of the capitals identified. There are many actors, agents and stakeholders in this activist landscape that intentionally or unintentionally use design, design thinking and other design processes to deliver their activism. Intentional use of design may involve the commissioning of professional designers by organizations or individuals with an activism orientation. It may also involve the use of design thinking and processes by those that are not professional designers in these same organizations. Both these applications of design may be considered as ‘design-orientated activism’ emanating from ‘traditional’ activist organizations. When designers themselves intentionally use design to address an activist issue or cause, whether working alone or within a not-for-profit design agency specifically set up with altruistic objectives, it can be considered as ‘design-led activism’. This distinction is confirmed by the preliminary results of a survey of the design press initiated by Ann Thorpe, a researcher at the Open Unversity in the UK.57 This book predominantly focuses on expressions of activism by designers, i.e. design-led activism, and the spaces that this occupies, in order to investigate the current state of the art.

Eco-design, sustainable design, designing for sustainability

Drawing lines between ‘avant-garde’ and ‘activism’

Isn’t all ‘avant-garde’ design a form of activism, as it represents the vanguard, the leading edge? The answer partly depends upon the purpose, intention and motivation of the designers and the scope of ambition to address the culture of design and/or the wider societal culture. Definitions of the avant-garde have remained remarkably consistent over the past 50 years, ranging from the ‘pioneers or innovators in any art in a particular period’58 to ‘any group of people who invent or promote new techniques or concepts, especially in the arts’,59 although others would widen the scope of avant-garde activities to experimental work in art, music, culture or politics.60 The avant-garde offers an alternative world-view, a counter-narrative to the dominant narrative. Poggioli observed that the avant-garde is solitary, loves its ivory tower, while courting an aristocratic body of the initiated, and that the ‘tragic position’ of the avant-garde art is that it must fight on two fronts simultaneously against the bourgeois culture of which it is an offspring and against popular culture.61 If this general characterization of the avant-garde is true, then the focus appears to be on changing an elite culture first before that group can then in turn extend influence over a wider socio-cultural or political group. Of great importance is whether the avant-garde is intent on serving him/herself and/or is indeed looking to benefit others. Knowing the intention of the avant-garde is again of primary importance in determining the extent of their activist ambitions.

Social movements embody activism by group action – a collective aspiration to maintain or change the existing situation. Those that seek change may be at the leading edge of societal or political change and so would seem to share some similarities with the more maverick character of the avant-garde. Yet, in the blurring of boundaries between one social class and another that occurred throughout the 20th century, and with the further democratization of channels of influence through the social networking phenomenon of the internet, the primacy of an elitist avant-garde to exert influence has perhaps been eroded. Does the avant-garde still exist in a design activist sense? And if it does, what causes and forms of activism does it favour?

A preliminary definition of ‘design activism’

Having scoped the broad territory of ‘design’ and ‘activism’, acknowledging that activism is focused around contemporary social, environmental and political issues, and seeing how current design theory and practice sit within the sustainability debate, it is possible to offer a tentative preliminary definition of design activism.

Design activism is ‘design thinking, imagination and practice applied knowingly or unknowingly to create a counter-narrative aimed at generating and balancing positive social, institutional, environmental and/or economic change’.

The emphasis on ‘counter-narrative’ is important as it suggests that it is somehow different from the main narrative, either that which is explicitly and collectively agreed upon by society as being ‘mainstream’ or being implicit in accepted behaviour (the underlying paradigm). The implication is that design activism voices other possibilities than those that already exist with a view to eliciting societal change and transformation. While those who unknowingly apply design thinking, imagination or practice in the cause of design activism are important – the unknown, non-intentional designers – it is those who knowingly use design, i.e. the design-led activists, who are the subject of investigation below.

Notes

1 Neutra, R. (1954) Survival through Design, OUP, Oxford, p314.

2 Erlhoff, M. and Marshall, T. (eds) (2008) Design Dictionary: Perspectives on Design Terminology, Birkhäuser-Verlag, Basel/Boston/Berlin.

3 Ibid. p104.

4 For example, see Julier, G. (2000, 2008) The Culture of Design, Sage Publications, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, 1st and 2nd edns, for historical and emerging perceptions of design and design culture; and a blog, Designfeast, www.designfeast.com/ for how the design conversation is changing.

5 Erlhoff and Marshall (2008), op. cit. Note 2.

6 Boradkar, P. (2007) ‘Theorizing things: Status, problems and benefits of the critical interpretation of objects’, The Design Journal, vol 9, no 2, pp3–15.

7 Fallman, D. (2008) ‘The interaction design research triangle of design practice, design studies, and design explorations’, Design Issues, vol 24, no 3, MIT Press Journals, Cambridge, MA, pp4–18.

8 Spangenberg, J. H. (2002) ‘Environmental space and the prism of sustainability: frameworks for indicators measuring sustainable development’, Ecological Indicators, vol 57, pp1–14.

9 For example, Al Gore, author, climate change lobbyist and ex-presidential candidate, US; Tony Juniper of Friends of the Earth, UK; Jonathon Porritt, author, chair of the Sustainable Development Commission, UK; Alex Steffen, Worldchanging, US.

10 Simon, H. (1996) The Sciences of the Artificial, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA; a republication of the original 1969 version.

11 Papanek, V. (1974) Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change, Paladin, St Albans, UK, p17.

12 See for example, Lewis, H. and Gertsakis, J. with Grant, T., Morelli, N. and Sweatman, A. (2001) Design + Environment: A Global Guide to Designing Greener Goods, Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield, p19; and Morelli, N. (2007) ‘Social innovation and new industrial context: Can designers “industrialize socially responsible solutions?”’, Design Issues, vol 23, no 4, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, pp3–21.

13 Thackara, J. (2005) In the Bubble: Designing in a Complex World, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, p2; Whiteley, N. (1993) Design for Society, Reaktion Books, London; Morelli, N. (2007), ibid.

14 Tarrow, S. (2005) The New Transnational Activism, Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

15 Tarrow, S. (1994) Power in Movement: Collective Action, Social Movements and Politics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

16 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Activism’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Activists; Google Directory (2008) ‘Society>Activism’, www.google.co.uk/Top/Society/Activism/

17 Porritt, J. (2007) Capitalism as if the World Matters, revised paperback edition, Earthscan, London.

18 Bonsiepe, G. (1997) ‘Design – the blind spot of theory, or, Theory – the blind spot of design’, conference text for a semi-public event of the Jan van Eyk Academy, Maastrict, April 1997.

19 Porritt (2007), op. cit. Note 17.

20 Smith, A. (1776) ‘Of the Nature, Accumulation, and Employment of Stock’, book 2, chapter 1, paragraph 18, available at www.adamsmith.org/smith/won-b2-c1.htm, accessed September 2008.

21 Porritt (2007), op. cit. Note 17.

22 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Social capital’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_capital, accessed September 2008.

23 According to Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Simon and Schuster, New York, cited in Porritt (2007), op. cit. Note 17.

24 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Financial capital’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_capital

25 Porritt (2007), op. cit. Note 17, p197.

26 Ibid. p183.

27 Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J-C. (1977) Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, Sage Publications, London; translated by Richard Nice from the French (1970) La Reproduction, Paris, Éditions de Minuit.

28 Bourdieu, P. (1986) ‘The Forms of Capital’, from J. E. Richardson (ed) Handbook of Theory of Research for the Sociology of Education, Greenwood Press, available at http://econ.tau.ac.il/papers/publicf/Zeltzer1.pdf, accessed September 2008.

29 Wikipedia (2008), op. cit. Note 24.

30 Porritt (2007), op. cit. Note 17, p183.

31 Ibid. p8.

32 Ibid. p169.

33 See, for example, Steffen, A. (ed) (2006) Worldchanging: A User’s Guide for the 21st Century, Abrams, New York; Mau, B. with Leonard, J. and the Institute without Boundaries (2004) Massive Change, Phaidon, London; Thackara, J. (2005) In the Bubble: Designing in a Complex World, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

34 Whyte, I. B. (1982) Bruno Taut and the Architecture of Activism, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

35 Dovey, K. (1999) Framing Places: Mediating Power in Built Form, Routledge, London and New York.

36 Farmer, J. (1996) Green Shift: Towards a Sensibility in Architecture, edited by K. Richardson, Architectural Press, Oxford.

37 Bell, B. (ed) (2004) Good Deeds, Good Design: Community Service through Architecture, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

38 Sinclair, C. and Stor, K. with Architecture for Humanity (2006) Design Like You Give a Damn: Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises, Thames & Hudson, London.

39 Some popular sources include: Wines, J. (2000) Green Architecture, edited by P. Jodidio, Taschen, Köln; Behling, S. and Behling, S. (2000) Solar Power: The Evolution of Sustainable Architecture, Prestel, Munich/London/New York; Lloyd Jones, D. (1998) Architecture and the Environment: Bioclimatic Building Design, Lawrence King Publishing, London; Vale, B. and Vale, R. (1991) Green Architecture: Design for a Sustainable Future, Thames & Hudson, London; Slessor, C. (1997) Eco-Tech: Sustainable Architecture and High Technology, Thames & Hudson, London; McHarg, I. (1992) Design with Nature, John Wiley & Sons, New York, first published by the Natural History Press in 1969; van der Ryn, S. and Cowan, S. (1996) Ecological Design, Island Press, Washington, DC.

40 Cranmer, J. and Zappaterra, Y. (2004) Conscientious Objectives: Designing for an Ethical Message, RotoVision, Mies, Switzerland, pp10–29.

41 Heller, S. and Vienne, V. (eds) (2003) Citizen Designer: Perspectives on Design Responsibility, Allworth Press, New York; Heller, S. and Kushner, T. (2005) The Design of Dissent: Socially and Politically Driven Graphics, Rockport Publishers Inc, MA, with cover design by Milton Glaser and M. Ilic.

42 See the orginal Ken Garland’s original manifesto, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Things_First_1964_manifesto; Adbusters, www.adbusters.org; Wikipedia, 2008, ‘First_Things_First_2000_manifesto’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_things_first_2000_Manifesto

43 Lasn, K. (2006) Design Anarchy, Adbusters Media Foundation, Vancouver, British Columbia.

44 Felshin, N. (1995) But is it Art?: The Spirit of Art Activism, Bay Press, Seattle, WA.

45 Ibid. p10.

46 Ibid. p19.

47 Vogt, W. (1949) Road to Survival, Victor Gollancz, London, quoted in Bell, S. and Morse, S. (1999) Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable, Earthscan, London, p7.

48 Dresner, S. (2008) The Principles of Sustainability, 2nd edn, Earthscan, London, p1.

49 World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) Our Common Future, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

50 Dresner, S. (2008), op. cit. Note 48, p2.

51 Ibid. p2.

52 Ibid. p4.

53 Dominski, A., Clark, J. and Fox, J. (1992) Building the Sustainable City, Community Environment Council, Santa Barbara, US, quoted in Bell, S. and Morse, S. (1999) Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable, Earthscan, London.

54 Rio de Janeiro ‘Earth Summit’ was organized by the United Nations in 1992 and was reported in a wide range of publications including Bell and Morse (1999), op. cit. Note 53 and Dresner (2008), op. cit. Note 48.

55 Spangenberg, J. H. and Bonniot, O. (1998) Sustainability Indicators – A Compass on the Road towards Sustainability, Wuppertal Paper 81, Wuppertal Institute, Wuppertal (was reprinted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and thus spread rather widely); Spangenberg, J. H. (2002) ‘Environmental space and the prism of sustainability: frameworks for indicators measuring sustainable development’, Ecological Indicators, vol 57, pp1–14.

56 Birkeland, J. (2008) Positive Development: From Vicious Circles to Virtuous Cycles Through Built Environment Design, Earthscan, London, pXV.

57 Thorpe, A. (2008) ‘Design as activism: A conceptual tool’, in Changing the Change: Design Visions, Proposals and Tools, Changing the Change conference, Turin, Italy, June 2008, Umberto Allemandi & Co, pp13, www.allemandi.com/cp/ctc/book.php?id=115=1, p11.

58 Fowler, H. W. and Fowler, F. G. (eds) (1964) The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English, 5th edn, Oxford University Press, London.

59 Wiktionary (2008) ‘Avant garde’, http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/avant_garde

60 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Avant garde’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/avant_garde

61 Poggioli, R. (1968) The Theory of the Avant Garde, translated by G. Fitzgerald, Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA, p37, p216, cited in Whyte (1982), op. cit. Note 34.