Contemporary Expressions:

Design Activism,

2000 Onwards

‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.’

Margaret Mead

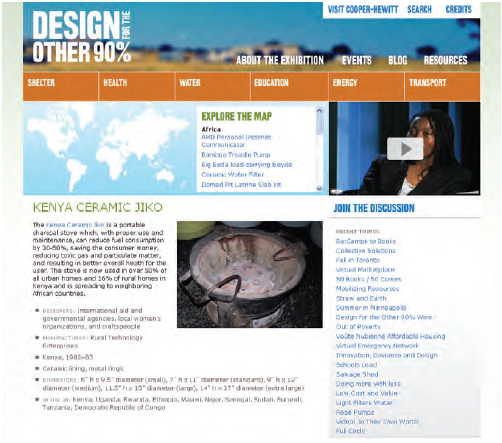

It seems that the interest of the professional design community (practitioners, academics, researchers, theorists, critics and writers) in design activism is gathering fresh momentum. A number of new organizations were established between 1999 and 2008 with an activist agenda focusing on architecture, social design, slow design and/or interdisciplinary design (see Figure 6.2, p170). Authors have explicitly named and explored ‘design activism’,1 while others have suggested new social dimensions for design practice2 or for increased societal participation in the design process.3 In 2005, a new biennale for social design was launched in the Netherlands – the Utrecht Manifest.4 In 2008, there was a gathering of more than 300 design researchers, teachers and practitioners examining diverse sustainability issues at the Changing the Change conference in Turin, Italy.5 Over the past few years, several design approaches are emerging to challenge the sustainability agenda and look beyond eco-efficiency. These include co-design, social design, slow design and metadesign (see Chapter 5, pp151–152). There are a number of new published works examining particular areas of design activism – in particular, architecture for humanitarian purposes,6 graphic and communication design,7 critical design,8 design and feminism,9 and the wider contemporary design and development agenda.10 In 2007, the Cooper Hewitt National Design museum, New York, focused on design for the world’s poor with an exhibition and publication entitled ‘Design for the other 90%’.11 So the design activism agenda appears to be in rude health, but how do we make sense of it?

The first part of this chapter looks at these activities and addresses a number of issues:

• How is theory informing action, and action informing theory?

• What are the contemporary expressions of design activism?

• Is there an emergent typology of design activism?

• What is the relationship between design practice, studies and explorations in design activism?

• What is the role of artefacts in design activism?

Sustainable Everyday – ‘quick’, ‘slow’ and ‘co-operative’ solutions

The second part of this chapter seeks to explore the range of expressions of contemporary design activism for two distinct audiences, the over-consumers (p86) and the under-consumers (p123). Why the distinction? The over-consumers must reduce their overall consumption by adopting new eco-efficient and positive behavioural strategies. To do this, designers need to educate by raising awareness of the real impacts of the over-consumers directly and indirectly on the global commons and on the under-consumers. Designers need to invoke new ideas about how to live a better life with reduced consumption. In contrast, the under-consumers are often struggling to meet basic physiological requirements for life. Yet they too need education and design solutions to gain access to appropriate levels of consumption that improve their quality of life.

The chapter predominantly addresses activism led by designers. This is design-led activism, although a few examples of designers collaborating with activist not-for-profit and other organizations are also given.

Thinking about Design Activism

‘Socially active design’: some emergent studies

There is a stream of consciousness and activity around what could be termed ‘socially active design’, where the focus of the design is society and its transition and/or transformation to a more sustainable way of living, working and producing. Ezio Manzini has long declared that sustainability is a societal journey, brought about by acquiring new awareness and perceptions, by generating new solutions, activating new behavioural patterns and, hence, cultural change.12 This approach guided his work with Francois Jégou and their colleagues at the Faculty of Design at Milan Polytechnic, Italy, who linked 15 design schools from around the world to determine how design could help to enable everyday design solutions to help in the physical and social transition to sustainability in the project entitled Sustainable Everyday.13 Each design school developed a range of scenarios for everyday living, looking at daily tasks and routines.14 These were developed into an enabling series of platforms based on whether the user required ‘quick’, ‘slow’ or ‘co-op’ (co-operative) solutions (Figure 4.1).15 Another study coordinated by Milan Polytechnic – Emerging User Demands for Sustainable Solutions (EMUDE) – involved the collation of data on how creative communities in Europe use existing resources and social innovation to enable positive system change.16 Each case study was subject to a qualitative social, economic and environmental evaluation in an attempt to define potential design research areas for products and PSSs that could be more efficient, widely accessible and easily diffused to other communities/ situations. In the UK, Guy Julier at Leeds Metropolitan University examined activism in the context of the social actors, stakeholders and structure of Leeds, a metropolitan UK city.17 Julier makes a case that design activism builds on what already exists, on ‘real-life processes from greening neighbourhoods to transforming communities through participatory design action’,18 rather than by advocating grandiose schemes which is the tendency of the urban planning process.

An emergent typology of contemporary design activism?

Mapping contemporary notions of design activism, Ann Thorpe of the Open University, UK, applies social sciences theory to examine the design literature in order to develop a conceptual framework.19 She defines activism as ‘taking intentional action to instigate change on behalf of a neglected group’, indicating a strong focus on the social dimension of the sustainability prism, but adds a caveat that the Earth’s ecosystems could also be regarded as a wronged group – so ecological design (and eco-design?) was a default representation of that group. She differentiated between designers as individual activists and designers as ‘activists for hire’, working for not-for-profit or public groups that espoused an environmental or social cause, but did not include cases of ‘corporate design activism’ such as greening of buildings or products. This perhaps creates an a priori judgement as to the efficacy of business versus the social and public sectors to deliver environmental or social positives. Nonetheless, the survey results were interesting.

An initial typology of action for design activism

Action | % of total | Explanation | ||

| Demonstration artefacts | 28 | Demonstrating positive alternatives that are superior to the status quo | ||

| Info/ Communication | 27 | Making information visual/tactile, devising rating systems, creating symbols, making physical links, etc. | ||

| Conventional actions | 13 | Proposing legislation, testifying at political meetings, writing polemics, conducting research, etc. | ||

| Competitions | 10 | |||

| Service artefacts | 10 | Humanitarian aid | ||

| Events | 9 | Conferences, talks, installations or exhibitions | ||

| Protest artifacts | 3 | Confrontational, even offensive, prompting reflection on the morality of the status quo | ||

| Source: Thorpe (2008)20 | ||||

Surveying the design press, using ‘protest event analysis’, a research methodology used by sociologists, Thorpe was looking for a typical ‘repertoire of actions’ (a term used by sociologists to talk about the activism of social movements) or what she calls a set of ‘jazz standards’ that design activists do/could adopt and modify. She coded about 15 per cent of 2000 identified cases in the design press and published some preliminary results detailing a typology of action (Table 4.1) and frequency of causes or focal issues (Table 4.2). A significant 41 per cent of actions were orientated around artefacts (subdivided as ‘demonstration’, ‘protest’ or ‘service’ artefacts) and 27 per cent around information/communication. The majority of design activist causes were of a human-centred orientation (63 per cent) rather than orientated to the cause of nature (38 per cent). In this survey, design activism tended to focus on the social and institutional dimensions of the sustainability prism, perhaps reflecting the bias in orientation of organizations in these recorded actions. However, this is a positive and welcome observation as it is the social–institutional axis of the prism that receives much less attention than the ecological–economic (eco-efficiency) axis.

Thorpe also noted that less than half of the cases studied (43 per cent) were instigated directly by designers themselves or by design-orientated non-profit organizations as opposed to other non-profits (schools, universities), public (government) and other organizations or partner-groups. Only about 15 per cent of the underlying activism strategies qualified as ‘visionary’, imagining or inventing new visions and actor/institution frameworks for the future (the remainder were reformist, i.e. building on what exists, or reactionary, i.e. taking past exemplars), although more than 65 per cent of these visionary strategies emanated from designers or design non-profits. This finding is perhaps not surprising given that design is fundamentally about creating and giving new visions form. What this emergent typology does not reveal, and nor do the equivalent repertoire of actions typically cited by sociologists (marches, demonstrations, boycotts, strikes, bearing witness, pamphleteering, vigils, etc.), is anything about the intentions and motivations of the designers, the intended target audience(s), the intended scale or reach of the action, the relational fit of the particular activism to the wider activism and sustainability landscape, and, most importantly, its effectiveness. The typology of action in Table 4.1 lists ‘competitions’, ‘events’ and ‘conventional actions’. These can potentially involve one or all of the other actions (artefacts and/or information/communication), so it is possible that the ‘design action’ and ‘design outcome’ are being blurred. Nonetheless, this is an interesting preliminary study and reveals that designers are definitely operating in activist mode.

Frequency of design activism causes

Cause | % of total | Explanation | ||

| Nature | 38 | Reducing impact, preserving wilderness, regenerative | ||

| Community enabling | 23 | Education, user involvement, sense of place, relationships | ||

| Human rights | 13 | Justice, affordability, accessibility and democracy | ||

| Cultural diversity | 11 | Immigration, religious diversity, ethnic/racial diversity, time (memorial) | ||

| Disaster relief | 9 | |||

| Range of causes | 4 | |||

| Health | 3 | |||

| Source: Thorpe (2008)21 | ||||

| Note: Biocentric or nature focus is 38 per cent of total, anthropocentric or social focus is 63 per cent of total. | ||||

Another approach to contextualizing design activism

There are a number of characteristics that could help define, orientate and contextualize the real focus and effectiveness of design activism (Tables 4.3, 4.4). The framework enables locating:

• the area of activism in the sustainability prism (Figure 1.11, p25)

• the area of activism from the maps of specific issues centred on the Five Capitals (Figures 1.1 to 1.8, pp3–15) plus 'man-made goods' capital model (see Figure 1.9, p16)

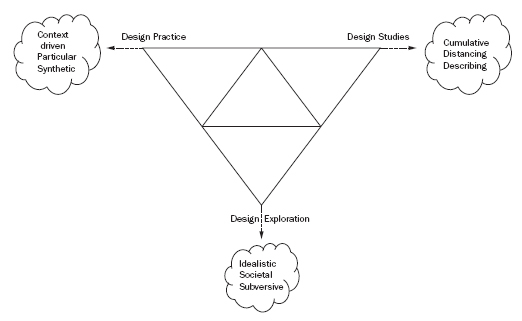

• the design project within a triangulation of design practice, studies and exploration domains – the latter is based upon the interaction design research triangle proposed by Fallman,22 which is given schematically in Figure 4.2 and Table 4.5

• the specific design context and design project detail.

Fallman’s triangle of design practice, studies and explorations

A checklist for characterizing design activism

Orientation |

Parameter |

Characteristics |

||

| Sustainability | Sustainability prism (see Figure 1.11, p25) Key sustainability issues |

Economic, ecological, social and/or institutional dimensions Climate change, resource depletion, food, water, ecological capacity, biodiversity, consumption and production, social injustice, poverty, new enterprise, technology and/or ‘other’ (specify) |

||

| Activist | Activist domains – based on the Five Capitals plus ‘man- made goods’ capital (see Figures 1.4–1.9) Activist subdomains |

Economics, technology, natural environment, institutions, individual (human perception, activity and behaviour) See Figures 1.4–1.9 to determine the relevant subdomains |

||

| Design context | Boundaries to context | Define boundaries, e.g. physical location, timeframe, cultural conditions, any constraints, etc. |

||

| Design project detail |

Design mode Design actions and/or output(s) Intention and dynamic of the artefact* |

Practice, studies and/or exploration (see Figure 4.2, Fallman’s triangle, and Table 4.5) Information/communication, concept, artefact*, built artefact/environment*, process, action, other – please specify Intention of artefact: Propositional artefacts explore or embody theory or practice expressing something that actually demonstrates its sustainability,23 suggesting visions for changing the status quo. Demonstration artefacts ‘demonstrate positive alternatives that are superior to the status quo’24 – perhaps only prototypes or small batch production. Service artefacts provided for ‘humanitarian purposes’.25 Protest artefacts ‘are confrontational, even offensive, prompting reflection on the morality of the status quo’.26 Entrepreneurial artefacts are designed and produced to challenge the status quo of the marketplace and are produced in small batches or are mass manufactured. Dynamic of a design artefact: The dynamic of a design artefact refers to whether it is closed, open or hybrid design. ‘Closed’ is complete, static, finished. ‘Open’ means it is intended that the user complete the design or is invited to modify |

||

| it (a halfway design or artefact, see p95). ‘Hybrid’ is a design artefact with ‘closed’ and ‘open’ elements or characteristics. |

||||

| Intention of project Target beneficiary(-ies) Target audience(s) |

Define purpose and goal(s) Define primary, secondary and/or other Define primary, secondary and/or other |

|||

| Note: * Artefacts – construed here as a man-made 2D or 3D physical object ranging from hand-held objects to buildings or landscapes. There are two dimensions to artefacts, their intention and their dynamic in relation to the end-users. | ||||

Parameters for interrogating the effectiveness, or reaching the goals/aims of the design activism

Score: Level 0 = ineffective, Level 10 = highly effective

Parameter |

Effectiveness assessment |

| Reaching the beneficiary or beneficiaries |

|

| Reaching the target audience(s) | |

| Achievement of goals/aims | |

| Effectiveness (impact on positive change) |

Fallman’s typical characteristics showing the differences of tradition and perspective between design practice, studies and explorations

Design practice |

Design exploration |

Design studies |

| Real | The possible | True |

| Judgement intuitive and taste |

Show alternatives | Logic |

| Competence | Ideals | Knowledge |

| Particular and contextual | Transcend | Universal |

| Client | Provoke | Peers |

| Create | Experiment | Explain |

| Change | Aesthetics | Understand |

| Involving and synthetic | Productive Societal, ‘now’ orientated Critique Political |

Distancing and analytical |

This framework provides a means of understanding the circumstances of any case study in design activism.

The natural candidate in Fallman’s triangle for design activism seems to be the category ‘design exploration’, which is referred to as design critique, art and humanities driven by the ‘idealistic, societal and subversive’. Fallman refers to Ehn’s ideas of ‘transcendence‘, the exploration of possibilities outside of the current paradigms of style, use, technology or economics – which seems to fit the notion of a counter-narrative. Furthermore, design explorations are seen as imagined futures, or scenarios, to show alternatives, to critique the existing, or to provoke, such as the ‘critical design’ of Dunne and Raby.27 However, the characteristics assigned by Fallman to design exploration (Table 4.5) can be extended to areas of design practice and design studies. Stuart Walker has recently proposed that pure design research should have the licence to create provocative experiments that step outside the boundary constraints of real-world economics (and current trends in higher education design research) by actively seeking to extend the role of design studies in examining the transition towards sustainability,28 aiming somewhere to the right of Fallman’s triangle. A coming together of the global design research community focused on sustainability in Turin in July 2008 at the Changing the Change conference indicates that design explorations can be central to encouraging the social learning journey required to move towards more sustainable ways of living and working, but that advances in design practice and design studies are equally important.29 The evidence of a growing practical canon of work for design for sustainability (DfS)30 indicates that there are many proactive designers already addressing the eco-efficiency axis of the sustainability prism through practice, i.e. they are effectively engaged in giving form to new practical outputs that are exploratory, since they contest market norms, and could be denoted as eco- or socio-preneurial. It seems reasonable to create a fifth category of artefacts (to accompany protest, service, propositional, demonstration, as proposed by Thorpe and Walker) that is overtly activist – the entrepreneurial artefact.

Design activism can be considered as something that can be an outcome of practice or explorations in real-life situations and/or academia. However, there is an implicit difference in the intended target audience and beneficiaries between practice and academia. The implication of the ‘practice’ context is that the outcomes are aimed at positive change in a real-life situation involving the wider culture and fabric of society. The implication of the academic-orientated ‘design studies’ context is that the target is predominantly, although not exclusively, the design culture of academia.

A critical facet of any activism is to have an understanding of the beneficiaries of the activist act(s) and its effectiveness in terms of scale and degree of impact on positive change (Table 4.4). Whether qualitative or quantitative, this feedback or assessment will help determine if this kind of activism is worth continuing, or if a change of strategy and tactics is needed.

The critical role of artefacts in design activism

As has already been noted above, artefacts can assume an activist role. ‘Activism’ artefacts can be for demonstration, service or protest31 or to present a proposition.32 Thorpe sees a protest artefact as being deliberately confrontational in order to prompt reflection on the morality of the status quo. Frequently these are one-offs and meet the criteria cited by Fallman’s ‘design explorations’. A demonstration artefact reveals positive alternatives that are superior to the status quo. These can occupy any part of Fallman’s triangle, design practice, research or explorations. A service artefact is one intended to provide humanitarian aid or aid for a needy group or population, for example in the event of a natural or man-made disaster. The service artefact clearly operates in design practice. Walker’s propositional artefact is a vehicle for the exploration of theoretical ideas (design research/studies), an embodiment of the ideas (design exploration) and an important element in advancing ‘sustainable design’ thinking and thus extending design practice. The idea of entrepreneurial artefacts as vehicles for activism in the market has also been suggested above.

Artefacts also embed ideas of inclusion or exclusion of individuals or particular social groups. So it is possible to talk about an ‘including artefact’ and an ‘excluding artefact’. Universal or inclusive design aims to minimize exclusion by ensuring the design can be used by most people most of the time. Left-handed people, on average about 15 per cent of the population, will certainly experience exclusion almost every day as most manufacturers minimize market risk by specifying right-handed options if a ‘universal’ orientation isn’t possible. A potential design activist strategy could involve positive discrimination by favouring the original excluded social group with a design intended only for them.

It seems that the typology of artefacts for activism needs further study. Many purposes can be ascribed to, and communicated by, an artefact. Knowing your purpose or intention will help determine what kind of artefact will achieve the specified goal. Reaching that goal depends upon communicating the correct message through the desired form and aesthetics. A good starting point is Susann Vilma’s Products as Representations and having a good understanding of the ‘aesthetic sign function’ which addresses cognitive and emotive messaging simultaneously.33

Activism Targeting the Over-consumers

If there is a critical mass population that can minimize future risk around the big global issues then it is the rich 20 per cent of the global population whose total mass and flow of consumption is causing most of the problems (see Chapter 3, p56). The need for change is clear, it is often a question of how to change.34 The arrangement in the following sections is an attempt to reveal some interesting projects, cross-cutting themes and approaches in the contemporary design activism landscape. It is to be hoped that the examples below show some fruitful areas for exploring potential actions and directions for change; here are some ‘designerly ways’ of being an activist. This should be seen as a curatorial collection of design activism expressions rather than an attempt to define a classification or typology. Some of the selected examples appear in one subsection, but could equally well illustrate principles in other subsections too.

Raising awareness, changing perceptions, changing behaviour

Sustainability is learning about living well but consuming (much) less; it is a social learning process and will involve moving from a ‘product-based well-being’ to thinking about products, dematerialized products, services and enabling solutions to satisfy our needs.35 A personal and collective realization of the importance of adopting cyclic rather than linear consumption and production is also implicit in achieving long-term sustainability. Frederich Schmidt-Bleek and his colleagues at the Wuppertal Institute and Factor 10 club suggest that a 90 per cent increase in efficiencies of resource use is required to ensure that an increasing global human population can be maintained within stable environmental and social systems.36 Heinberg suggests that the rate at which resources are being consumed makes resource use efficiency and avoidance of resource depletion the key challenges of the early 21st century.37 An intertwined strategy is required: the strategy to directly improve the eco-efficiencies of the product or service throughout its life cycle; and the strategy to deliver ecoefficiencies indirectly by changing behaviours. To make this strategy effective also means engaging with academic, social, political and commercial agendas.

Redirective theory and practice

The first group of people that urgently need to change their behaviour are the designers themselves. Various design theorists and critics have been touching on the sustainability theme since Richard Neutra’s 1954 book, Survival through Design,38 but it was not until the early 1990s that the discourse on the environmental impacts of design came of age (see pp47–48) and only in the past five years or so that attention refocused on design in the social arena (see pp152–153). Concurrently, there have been a number of emergent new design approaches that have gathered within the sustainability canon. These receive more attention below (Chapter 5) but include critical design,39 slow design,40 co-design41 and metadesign.42 Such approaches are an attempt to reframe design theory and practice. Anne-Marie Willis talks about ‘redirective practice’ which requires a deep understanding of what we currently design that is unsustainable, in order that design as ‘preconfiguration and directionality’ can move towards more sustainable solutions.43 Design’s preconfiguration and directionality echoes the sentiments of Tony Fry who noted that ‘design designs’.44 The objective of redirective practice is ‘sustainment’, a complex concept that eludes one explicit meaning but gathers around the idea of ‘sustaining that which sustains’.45 Transforming thoughts and perceptions of the culture of design about sustainability seems a crucial undertaking for the design activist that is now gathering significant attention in design research, studies and practice in Europe and worldwide.46

Communication by information

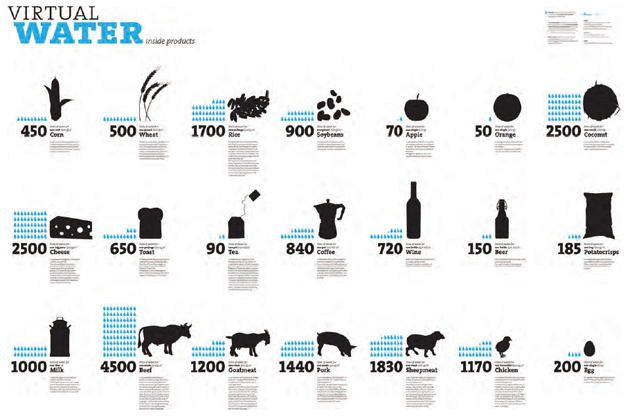

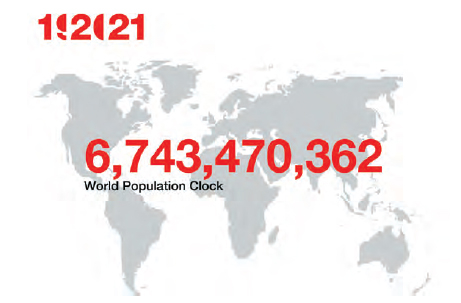

Organizations such as Adbusters have long raised the spectre of over-consumption and its promulgation by the multinational corporations and the media, although Janet Wolff is cautionary about how effective this kind of culture jamming is compared with genuine critical political debate.47 Others are now finding ways of engaging people to question their own responsibilities in the way they consume. Giraffe Innovation’s Changing Habbits project with the Royal Society of Arts, UK, enables individuals to enter specific consumption criteria about their use of energy, water, food, electrical goods and waste generation in the home, plus transport patterns, in order to calculate their consumer ‘habit’.48 The data from this habit are converted into a 3D rendered image of an androgynous human being whose head, body and limbs are distorted from the ‘ideal habit’ to graphically show where the consumer’s maximum environmental impacts, in terms of tonnes of carbon dioxide per annum, are being made (Figure 4.3). Another project that utilizes familiar images in new configurations is Worldmapper comprising several hundred cartograms, where land mass from a standard world projection is distorted for each country according to the metric being measured (Figure 4.4). These maps transmit strong visual messages that are more easily assimilated than the mass of statistical data that creates them. Simplifying the message seems an important challenge. Timm Kerkeritz’s Virtual Water poster graphically illustrates the consumption of water associated with everyday food and drink, and on the flip side reveals the water footprint of consumers in countries around the world (Figure 4.5). A recently initiated project called 192021 focuses on the challenges that are facing the world’s global cities in a looped slide show (Figure 4.6). One slide shows a real-time counter of world population growth – the world population clock – which illustrates the net increase of newborns minus deaths each second, adding to future consumption demands. The Story of Stuff by Annie Leonard also uses the web to deliver a 20-minute video, using clever graphics and a riveting storyline.49

Changing Habbits, Giraffe Innovation/Royal Society of Arts

Finding new ways to communicate requires imaginative use of design to penetrate beyond the ‘white noise’ (many random signals of equal intensity) of contemporary life.

Communication by concept, prototype or artefact

Concept designs are frequently deployed to challenge an existing canon or imagine future possibilities. They often emerge as the result of design competitions, as explorations for clients, from research projects, and/or from the development of a personal design ethos, portfolio or body of work. The MIT Smart Cities project is a concept generation laboratory, imagining everything from growing your own house (Fab Tree Hab) to stackable electric cars for dense urban areas (CityCar).50 The strength of these designs is to ask ‘what if’, a central question to any design exploration.51 It is most important to ask ‘what is the intention of the designer of these concepts and to which audience is he/she reaching?’

Worldmapper cartograms: Standard projection (top) and ‘absolute poverty’ (bottom)

Danish designer, Mads Hagstroem, created the brand FLOWmarket to generate ‘thought awakening’ by taking ubiquitous products, such as bottled water, and interrogating their existence in our lives (Figure 4.7). FLOWmarket is a global brand crossing cultural boundaries. Hagstroem’s nonchalant arrangement of facts and texts in his ‘scarcity goods collection’ reveals the relationship between flows of the individual, the collective and the environment. Arranged in a shop, his products reveal the vacuity of their supermarket cousins and contest their right to exist.

Virtual Water poster by Timm Kerkeritz

Project 192021 world population clock

Clean tap water by Mads Hagstroem, FLOWmarket

Lunchbox Laboratory by Futurefarmers and National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Since 1995, Futurefarmers in San Francisco have consistently promoted public projects to raise awareness around issues of growing local food, permaculture systems and biofuel production (Figure 4.8). Their quirky prototypes and experimental artefacts drive home consistent messages of autonomy, self-help, DIY culture and downshifting. Their DIY Algae/Hydrogen Bioreactor, 2004, explored the feasibility of making hydrogen from algae at home, using easily obtainable components. A follow-up project called Lunchbox Laboratory, 2008, in collaboration with the National Renewable Energy Lab, was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. It is a portable laboratory that enables schoolchildren to collect local algae strains, culture them and test how much hydrogen each strain can produce. It creates the potentiality of finding more efficient strains faster and is analogous to distributed computing networks, where the power of many individual networked computers is brought together, for example, for climate modeling.52

Communication by event, story or scenario

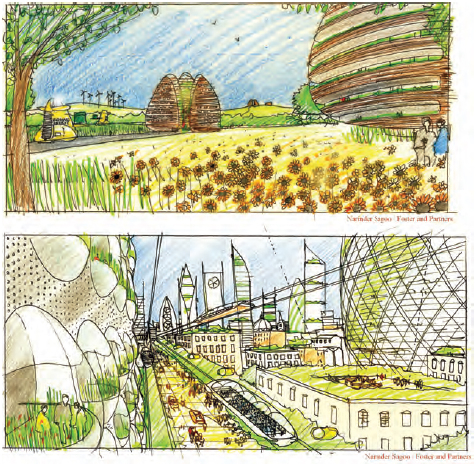

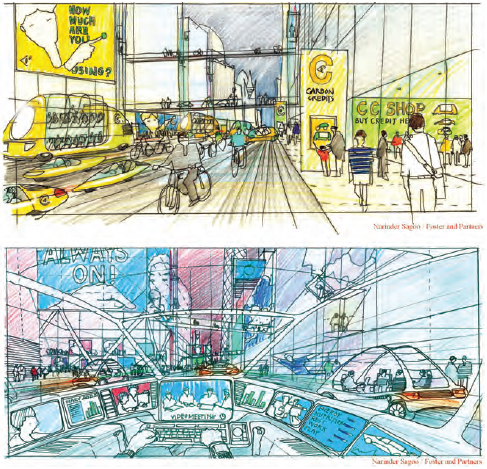

An event by a professional activist group provides a challenge for the commissioned designers. Thomas Matthews highlighted International Buy Nothing Day for its client, Friends of the Earth, UK, by creating ‘No Shop’ in central London. It sold nothing but was a repository for information about the campaign (Figure 4.9). In another example, the UK government commissioned an illustrator to show four possible scenarios for sustainable travel in 2020 (Figure 4.10). Powerful visual communications not only tell stories but elicit strong cognitive and emotive responses, engaging the viewer.

No Shop by Thomas Matthews

Sustainable Everyday – an international design project, led by Milan Polytechnic – deployed scenarios and storytelling to reveal possibilities for quick, slow and co-operative enabling solutions for urban dwellers to meet their needs (see Figure 4.1). Scenarios, built by using a participatory approach in design workshops around the world, focused on aspects of everyday life in the city from moving around, getting and cooking food/water/energy, leisure activities and work/family life. The objective was to create a range of solutions that were enabled or facilitated individually or collectively using existing resources as much as possible. Central to the project was the idea of elevating the well-being and capability of the people involved. Some common principles and features emerged from the scenarios (Table 4.6). These reflect many of the characteristics defined earlier by the Postmodern ecologists (see p42) but also introduce a transformational shift from individually owned products to collectively organized products and PSS coordinated by increasing system/social connections and networks.

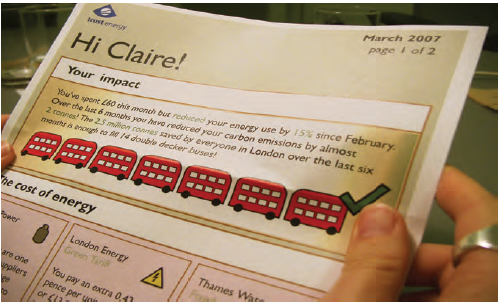

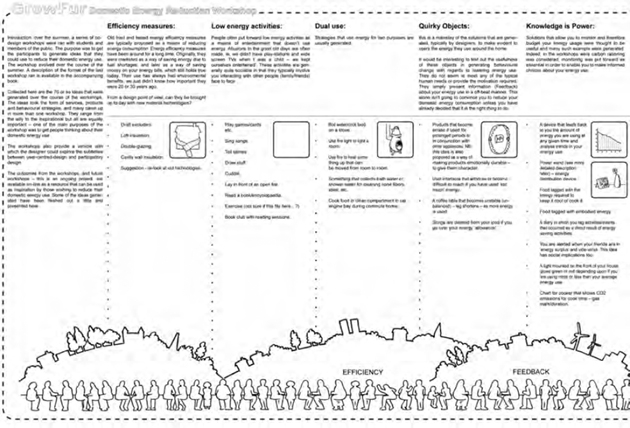

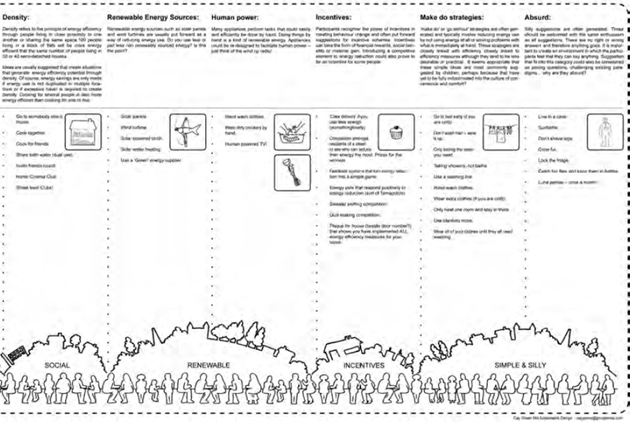

Communication by project

RED, a design group with the Design Council, UK, ran a number of projects aimed at involving the public in design-led projects by an approach called ‘transformation design’.53 One project, called Future Currents, examined how households could be made aware of their impact on global warming and be encouraged to reduce their carbon footprints. Four top-level behavioural strategies emerged from the series of workshops: home monitoring, rank and reward, peer power and hot products (Figure 4.11). The diversity of the strategy outcomes testified to the importance of the participatory design approach (see Chapter 5) and revealed the limitations of products and services alone to promulgate a significant change in behaviour. Cay Green came to a similar conclusion in a postgraduate study focusing on changing energy consumption in domestic households. She designed a tool for consumers in the form of a booklet called Grow Fur that showed how households could run their own ‘workshops’ to co-create and co-design their own solutions to fit their lives (Figure 4.12).

Ways of making and producing

The global economy enables transnational corporations to manufacture their brands anywhere that competitive labour prices and raw or manufactured materials can be readily brought together. This ‘distributed’ manufacturing relies entirely on fossil fuels to move raw materials, components and finished products around the globe. Peak oil will challenge this model of manufacturing as the proportional cost of oil rises in each part of the supply and distribution chains. The growth of the green, ethical and ‘organic’ consumer markets since the mid-1980s54 and more recent attention to ‘localization’55 is also affecting what, where and when products are made. This trend appears set to continue.

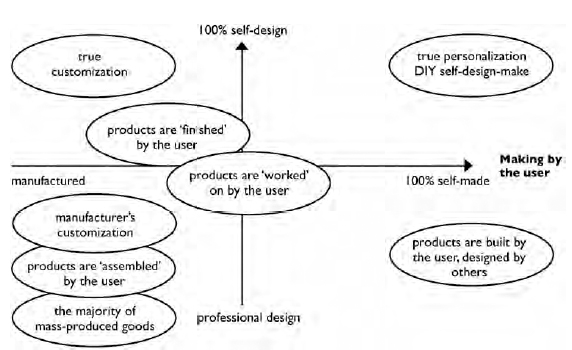

Other more fuzzy trends are contesting the way things are made. Demands for products that are more easily personalized or customizable, tend to offer the promise of more durable emotional relationships.56 The inextricable rise of the internet in everyday life is leading to much experimentation in ways of making and the emergence of co-created, co-designed and replicable designs is a plausible reality (see Chapter 5, ‘Designing Together’). In the search for more meaning there may be a shift in the balance between what is made by manufacturers, designed by professionals, and what is self-made, designed by non(professional)-designers57 (Figure 4.13).

Halfway products

In a ‘halfway’ product, the designer/maker/manufacturer only takes the product so far, leaving a space for the user to complete the making.58 The user embeds their own creativity, stories and mistakes in the process of finishing the product, thereby cementing a personal narrative, memory and associations that differentiate this product from others manufactured at the same time. Halfway products differ from examples of car customization where the user has taken a standard production car, removed elements and added their own ‘customized’ element. They also differ from ‘mass customization’ or ‘mass personalization’, i.e. manufacturers offering a range of colours or model types, or offering a standard model with variable elements, e.g.the mobile phone with clip-on external casing.

UK government’s future transport scenarios

The orientations and guidelines for the Sustainable Everyday project

General principles |

| Think before doing. Weigh up objectives and ethical considerations Promote variety. Biological, socio-cultural and technical diversity Use what already exists. Reduce the need for the new. Minimize intervention. Enhance what is there |

Quality of context |

| Give space to nature. Protect natural environments and promote ‘symbiotic nature’ |

| Re-naturalize food. Cultivate naturally |

| Bring people and things together. Reduce demand for transport |

| Share tools and equipment. Reduce the demand for products. Foster new forms of Socialization |

System intelligence |

| Empower people. Increase participation |

| Develop networks. Promote decentralized, flexible forms of organization. Develop learning systems with feedback that can be reorientated |

| Use the sun, wind and biomass. Reduce dependence on oil. Alternative energy systems minimizing CO2 emissions |

| Produce at zero waste. Promote forms of industrial ecology. Closed loops of materials and cascade energy |

| Source: Manzini and Jégou (2003)59 |

Future Currents project, RED, the Design Council, UK

Tache Naturelle by Martin Ruiz de Azúa builds on commercial ideas of pottery painting in cafés by encouraging the user to take a biscuit-fired vase and complete its decoration, but de Azúa suggests that the user secrets it in the urban or rural landscape and lets nature provide the final serendipitous markings (Figure 4.14). This involves the user imagining stories, trying out different locations and retrieving it after varying time periods elapsing; in short, each user creates a different set of circumstances for ‘finishing’ the vase. In a more direct and obvious challenge, Natalie Schaap confronts the user with a real and symbolic chair, An Affair with a Chair. She offers a chair frame which the user must complete to obtain the final use-value and full functionality of a chair (Figure 4.15). As the name of her product suggests this product ‘elopes’ with its user and a relationship begins. Both these approaches attempt to create added layers of meaning for the user by involving them tangibly in completion of the form giving. In doing so, the aesthetic is made personal.

Grow Fur by Cay Green

Ways of designing and making

Tache Naturelle by Martin Ruiz de Azúa

A fictional new brand, ‘do’ was created by Kesselskramer, a Dutch publicity agency which engaged the Droog Design collective to interpret the brand. Ten designers exhibited in Milan in 2000 under the banner ‘do Create’, demonstrating new possibilities for creating new objects in our lives, objects embedded with new meaning by the user finishing the product.60 Examples include Marijn van der Poll’s ‘do Hit’ metal cube that the user shapes into an armchair by using a sledge hammer (Figure 4.16); Martí Guixé’s ‘do Scratch’ a transparent box coated in black paint that the user scratches to permit the light rays to escape. An emotional mortar with the brand is forged by the user becoming an active participant in the final creation.

An Affair with a Chair by Natalie Schaap

Modular evolved products

Traditional ways of organizing and managing mass industrial production have largely been uncontested since the mid-19th century, because they support a well- understood and risk-limited business model. This model also generates huge quantities of stuff, much of it on a rather short-lived journey to a landfill site. A study by the Dutch Eternally Yours Foundation revealed that 20–90 per cent of discarded domestic electrical products were still working and offered the original functionality.61 If functionality had not broken, then the relationship between user and product clearly had. In this super-saturated world of stuff, the ‘real world’ for the over-consumers, Walker62 suggested that a radical new design and manufacturing approach is required. His design of a digital clock separates the functional components from a ‘chassis’, the latter being a white armature or canvas (Figure 4.17). Over time, the functional components can be replaced, repaired and upgraded as required. In Three White Canvas Clocks, the user has control over the final form, through modification of a number of variables. Function and utility can literally be mixed in a visual palette chosen by the user. The symbolic meanings are therefore at the control of the user. The user even has to ‘tend’ his/her clock by supplanting fresh fruit to provide the living battery. Such a system confers some psychological advantages to the user, allowing them to evolve and extend the relationship with the product. This type of product may require new business models and manufacturing systems to deliver commercial viability.

do Hit chair for Droog by Marijn van der Poll

Three White Canvas Clocks by Stuart Walker

Ethical products

The history of ethical product manufacturing for the consumer economy commences in the 1970s with the Body Shop cosmetics chain and Ben & Jerry ice cream that pioneered brands with strong ethical values as a means to differentiate these companies from their competitors. Wider consumer market demand did not emerge until the late 1980s in Britain, when magazines such as Ethical Consumer examined the credentials and products of companies espousing to be ethical.63 Since then new labels and certification schemes have emerged to give the consumer information on a wide variety of ethical concerns. The Fairtrade label that ensures a fairer percentage of profits goes to the primary grower, is perhaps the best known. Industries have adopted their own methods of communicating their ethical standards. For example, in the fashion and clothing industry there is a number of campaign groups that have highlighted sweat shop labour issues, such as Labour Behind the Label and the Clean Clothes Campaign, and even large commercial companies promote their ethical stance, for example, American Apparel lists its credentials with a label that notes ‘Made in Downtown LA, Sweatshop Free’.64 Are these initiatives activist? Yes, as they look after the interests of neglected and minority groups and prevent their exploitation. Yet, most of the above examples are generally not led by designers. For design-led activism around ethical products we have to turn to the likes of Adbuster, with its campaign around Blackspot sneakers and boots made from organic hemp in a Portuguese union shop,65 or to individual designer-makers determined to forge new models of production. In 2000, Natalie Chanin set up a cottage industry making bespoke garments under an initiative called Alabama Chanin.66 She revived many crafts skills beginning to dwindle in the local community and encouraged the women to come together in circles to stitch, quilt and embroider, often using reused materials.

Replicating machines, brokered manufacturing, downloadable designs

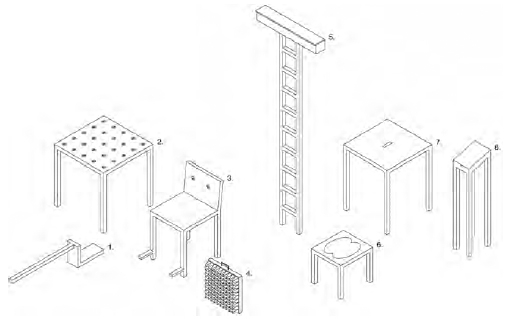

The ‘information age’, facilitated by the inextricable rise of the internet, is generating new visions of manufacturing. RepRap (Replicating Rapid Prototyper), designed by Adrian Bowyer and Vik Oliver at Bath University, is a self-copying 3D printer that builds components by building up layers of plastic (Figure 4.18). Once one RepRap has been built, it can then replicate itself, as indeed happened in the laboratory at Bath on 29 May 2008. As the designs for the machine are available under the GNU General Public License, anyone can build and upgrade one. This potentially opens up radical new ways of organizing manufacturing, servicing and maintenance for elements, components or whole products (see more in Chapter 6, pp174–175). An alternative system is being offered by Ponoko, New Zealand. The company will receive designers’ flatpack designs, find the buyers and get specific manufacturers to cut and deliver them. Ponoko also offers an online space for co-creation. This personalized manufacturing platform permits make-on-demand. Taking it one stage further there are a number of platforms offering downloadable designs via the internet. Kith-Kin has a shop of downloadable designs for chairs, paper objects and diverse creative ‘inventions’.67 Paper Critters offers a web platform and software tools for creating paper toys.68 The cutting plans can be downloaded by the users. To date, more than 5000 contributors have unleashed their creativity using this facility.

RepRap by Adrian Bowyer and Vik Oliver

Bonding with the workers – meaningful production

While the workers are largely forgotten in the manufacturing process, some designers have taken an interest in these unsung labourers. Connecting Lines by Judith van den Boom is an ongoing collaboration, commenced in 2007, with workers in a bone china factory in Jingdezhen, China (Figure 4.19). She is a catalyst, facilitator and designer running workshops and poetry readings with the workers. The intention is to humanize processes and encourage collective intelligence to create a ‘smart factory’ where designers and employees co-create, co-design and co-make. How workers are engaged with the act of making seems of paramount importance in a society focused on the good life (at work and at home). Proto Gardening Bench by Jurgen Bey for Droog was the output from a larger project, Couleur Locale, examining the revitalization of the communities of the town of Oranienbaum, Germany (Figure 4.20). This ephemeral seating is a conceptual design made from garden waste harvested at different times of the year by the local community. Waste is compressed and bonded in a resin matrix. As the seating weathers, it is slowly returned to nature and the cycle begins again.

Connecting Lines, a project with factory workers in Jingdezhen, China, by Judith van den Boom

Proto Gardening Bench by Jurgen Bey for the Oranienbaum project for Droog

Experiments in bio- and techno-cyclicity

Closing the loop by seeing waste as food is an important principle in realizing eco-efficiency improvements. McDonough and Braungart refer to biological and technological materials as nutrients that can nourish new generations of products.69 The possibilities of growing furniture in-situ are being investigated by everyone from arboriculturalists to designers. Yael Stav of Innivo Design works with Plantware in Israel to create living plants that are functional household and office objects (Figure 4.21). Christopher Cattle of the UK’s Grown-Furniture promotes the skills and simple technology of training and grafting plants to grow your own stool, taking about five years for a three-legged stool of sycamore.70

Plantware, living functional plant structures, by Yael Stav of Innivo Design

Recycling synthetic plastics is fraught with difficulties because of a recalcitrant plastic industry protecting its virgin markets, supply–demand and perceived issues of the quality of recyclates and because the plastic waste is highly distributed once it enters the retail chain. However, recycling can make good business sense and has attracted attention from designer-makers to international manufacturers. Richard Liddle of Codha Design is experimenting with ways of using recycled high density polyethylene (HDPE) to create new domestic seating (Figure 4.22). A continuous ribbon of re-pigmented HDPE extrusion is applied manually to a mould creating one-offs. This celebratory use of plastic recyclate contrasts with other examples, such as the REEE chair by Sprout Design (Figure 4.23) where the recyclable (in this case Sony PlayStation cases) is invisible, invoking a ‘sustainability by stealth’ approach. Since Herman Miller, the international office furniture manufacturer, launched its classic Aeron chair in 1991 using components from recyclate, the company has continued to refine its designs. Its latest design, the Celle chair is 99 per cent recyclable at end-of-life and includes 33 per cent of its components from recyclate.71 These approaches position the cultural acceptability of their design outcomes in different ways. Codha Design make a significant aesthetic statement about ‘closing the loop’ by creating a practical yet ‘propositional or demonstration’ artefact (see pp83, 85) deliberately trying to go beyond what the great US industrial designer Raymond Loewy called ‘most advanced yet acceptable’ (MAYA),72 while Sprout Design and Herman Miller demonstrate recycling as a sensible business proposition, and so tacitly acknowledge MAYA’s boundaries, which are determined by reducing capital risk while maximizing potential profit per unit production.

Codha chair by Richard Liddle, Codha Design

REEE chair by Sprout Design for Pli Design

Eco-efficiency improvements

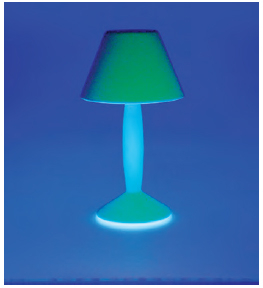

Improving the eco-efficiency of any design artefact or service is an act of activism to reduce impacts on the world’s ecosystems (and humankind). While this is clearly different from an activist who takes action to protect a habitat, ecosystem or specific species, reducing the impacts of our production and consumption is of great importance. Since the turn of the millennium, a significant body of work has been published on design that aims for improved eco-efficiencies in order to lighten our impact on the Earth’s resources, habitats and ecosystems (see pp47–48). There are legion examples showing that designers of all persuasions, and some enlightened clients and manufacturers too, are striving to turn rhetoric into new eco-design or ecological design practice.73 While these examples are many, and growing, many have not achieved critical mass in the markets. A good analogy is to walk around a typical Western supermarket and see the proportion of organic food in relation to all the rest of the food being sold. Organic food is present but the vast bulk of food produced, bought and consumed, originates from inorganic systems requiring high oil energy inputs and oil-dependent derivatives (oil-based fertilizers, pesticides). This same picture emerges scanning across other consumables (cleaning products, cosmetics and paints) to durables (from houses to cars to electrical/electronic goods and fashion). With housing, transportation and food governing almost 70 per cent of total environmental impacts in the 2006 in the (then) 25 countries comprising the European Union,74 the eco-efficiency challenge remains daunting. Recalcitrant industries, housing developers and governments (what we may call the ‘business-as- usual’ majority) need to be shown that there is a strong business case for ecoefficient designs. The evidence is just starting to show in the latest trends predicting that eco-products will be an emergent area for many manufacturing sectors in the next few years.75 Any designer prepared to take on this role, and enlist the silent client of the environment – nature – is a default activist. There is a growing cadre of e-zines dedicated to celebrating these eco-design activists, including Treehugger, Inhabitat and Worldchanging.76 Many eco-efficient products utilize materials with an inherently lower impact (recycled, biological origin materials) and reduce energy during the manufacturing and/or during the use phase of the product. The thinking behind these products uses existing technological approaches, for example, Trevor Baylis’s MP3 player (Figure 4.24), utilizing proven wind-up energy technology to more tangential solutions, such as Martí Guixé’s Flamp, a wooden table lamp coated in phosphorescent paint that absorbs UV light and re-emits it when darkness falls (Figure 4.25). While the innovations are many, few products are designed to be taken back by the manufacturers at end-of-life, so there is still significant progress required in this area to ‘close the loop’ and ensure eco-efficient recycling of valuable materials. That these manufacturers and designers are actively striving to make their products more efficient is laudable, but measuring their true eco-effectiveness remains problematic, especially since studies show that eco-efficient products can generate a negative rebound effect – that is when the users spend the money or energy saved from these products in other areas in their lives.77 In a worst case scenario, the successful sale of millions of eco-efficient products into new markets has the potential to actually increase overall energy consumption.

MP3 eco-player by Trevor Baylis

Flamp by Martí Guixé

Design concepts

Smart Cities is a range of diverse mini-projects at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), US, united under a research focus on ‘intelligent, sustainable buildings, mobility systems and cities’ that is not constrained by traditional boundaries.78 While techno-centric thinking dominates most of the Smart Cities concepts, other MIT-initiated projects show plausible biocentric tendencies, such as the Fab Tree Hab, a growing house of living trees grafted onto on computer numeric controlled (CNC) reusable structures (Figure 4.26) designed by the Human Ecology Design team (now Terreform 1). This is blue sky thinking about using existing and new technologies with networked intelligence, as illustrated in the CityCar, a stackable two-seater electric vehicle for one-way journeys from Vehicle Stacks at suitable nodes in the city (Figure 4.27). The analogy is the stackable supermarket or airport trolley – to be used when needed. Given the international profile of MIT, the primary intention of these exploratory Smart Cities projects may be to encourage further R&D funding to convert the concepts into reality, but the huge media attention also ensures elevating general awareness among research communities and the general public.

Fab Tree Hab by Terreform 1

Prototypes

At the Amsterdam AutoRAI show in January 2007, yet another prototype car was launched. However, this one was remarkably different. It did not emerge from the R&D department of the global car manufacturing industry, it was the outcome of a collaborative open source design project involving the Netherlands Society for Nature and the Environment, the Technical Universities at Delft, Eindhoven and Enschede. The technical drawings and other design details for ‘c,mm,n’, the zero-emission hydrogen engine car (Figure 4.28), are available for download on the internet allowing others to participate in refining the design.79 While the merits and eco-efficacy of hydrogen fuel is still open to debate, the process of open source design is to be lauded.

CityCar by MIT Smart Cities

c,mm,n open source car, the Netherlands

Boase housing development, Copenhagen, by Force4 and KHRAS

A young Danish architecture practice, Force4, teamed up with KHRAS to win the Home of the Future Competition organized by the Danish Building Research Institute and RealDania in 2001 (Figure 4.29). Their first-prize concept, Boase,80 provided affordable housing on stilts over a contaminated post-industrial site planted with trees for phyto-remediation of the toxins in the soil. With more than 150 of these brownfield sites identified in Copenhagen, the land area is substantial, yet housing development is not normally approved on these types of sites by the authorities. Phase two of the project ensued in 2005 with a 1:1 scale mock-up examining the basic technologies required for site decontamination, development of solar membranes and the energy-gathering potential of the facade, plus optimization of the spatial organization of each dwelling. In early 2009, Boase is scheduled to be applied to the first site in Copenhagen, demonstrating just how much persistence is required to activate more radical ideas. This project steps beyond eco-efficiency and aims to build new communities while regenerating the biological capacity of the site, something advocated by Janis Birkeland in her call for ‘positive development’ not ‘sustainable development’.81

Contesting meaning and consumption

‘Green’, ‘ethical’ and ‘sustainable’ consumption received consistent attention from the late 1980s onwards but these approaches gather around abstract notions of causing less damage to the environment. In the design debate, the human, and hence social, imperatives of consumption received less attention. The real question rests on how we can consume to improve well-being and quality of life and simultaneously reduce our environmental footprint. Understanding what motivates us to consume differently seems to be important. Researchers turned towards needs theory to understand the physiological, psychological and social functionings that contribute to well-being.82 Others examined how design can offer substantive improvements to deepening our relationship with products in order to extend the lives of products while enriching the users’ lives;83 how a new model of well-being posited on balancing the individual against economic, environmental and social factors could refocus designers and manufacturers;84 and the role that design can play in cementing powerful emotional and experiential relationships with objects.85

Ways of deepening and extending relationships throughout the lifetime of a product, the introduction of new rhythms and experiences, and shifting consumers from products to dematerialized services form the bedrock of designers searching to deliver new meanings to artefacts and hence to the act of consumption.

One-Night Wonder, The Lifetimes Project and No Wash Top, 5 Ways Project

Improving human–product relationships

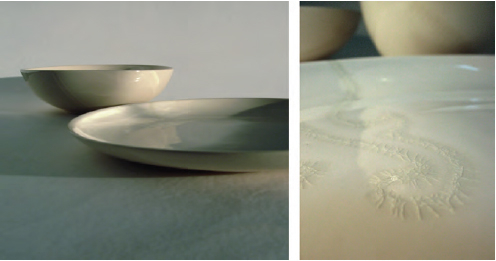

Two design research projects examining our relationship with textiles and clothing reveal the nuances of design detail and their considerable ramifications for environmental impacts throughout the life cycle of the clothing. The Lifetimes Project86 and the 5 Ways Project87 think about how ecological values are embedded in the various components/elements of a fashion design and how they enable new notions of washability, locally made, multi-life designs and offer options for updatability (Figure 4.30). Other strategies to make the consumer look afresh at the products that surround them include a direct approach by Dick van Hoff whose ambition, via his project Tyranny of the Plug (Figure 4.31), is to liberate us from having to plug into the domestic electricity supply by creating high-specification engineered kitchen products that reinstate the joy of manual methods of food preparation. Simon Heijdens aims for a slow dawning and realization by the user that the product is evolving, growing. The minute cracks in the glaze of Broken White reveal themselves more and ‘grow’ as the plate is used more (Figure 4.32). Monika Hoinkis finds ways of reintroducing us to objects we no longer see by removing vital components that force us to become intimate with the object in a new way, to find new poetry in the mutual existence of person–object, to renew the vigour of the relationship (Figure 4.33).

Focusing on experiences not objects

Life’s experiences and the social relationships we develop tend to be a forceful arbiter of what we make of life. Lawrence and Nohria88 observed that we are ‘hardwired’ with four innate, universal, independent yet inter-connected drives:

• to acquire objects and experiences that improve our status relative to others

• to establish long-term bonds with others based on reciprocity, of mutual caring commitment

• to learn about and makes sense of our world, which is largely our own social creation, and of ourselves

• to defend ourselves, our families and friends, our beliefs, and our resources from harm.

The acquisition of objects is an important drive that the design of artefacts can help satiate, but the other drives are orientated around experiential, social, existential and survival factors. Moving beyond form and function, some designers use the object as a conduit to an experience ‘beyond the object’. Swedish design agency Front, created a wallpaper that absorbs ultraviolet light, emitting mood altering glows as darkness falls. Front also initiated Tensta Konsthall, an interior design project where change is deliberately built into the design elements (Figure 4.34). As time progresses the elements fade, providing a slowly evolving time marker to change we tend not to see. Playing with the emotions of time was a key aim of Thorunn Arnadottir’s Clock, comprising an electric cogwheel on which a string of coloured beads sits (Figure 4.35). As the clock turns, the beads change position. Blue beads represent five minutes, orange and red the hour points, gold for midday and silver for midnight. In a powerful emotional and symbolic moment, removing the beads from the clockface and using them as a necklace liberates the wearer from the ‘clock time’ to your own ‘free time’. Arnadottir’s invocation of a different sense of time is a central theme to many designers working within the ‘slow design’ approach (see Chapter 5, p157).

Tyranny of the Plug by Dick van Hoff

Broken White by Simon Heijdens

Living with Things by Monika Hoinkis

Tensta Konsthall by Front

Clock by Thorunn Arnadottir

The Hug Shirt™ by CuteCircuit

Another time-enabled experience is initiated by CuteCircuit’s The Hug Shirt™, where electronic circuitry includes sensors that measure touch, skin warmth and the heartbeat of the sender and actuators that recreate those sensations in the recipient’s shirt (Figure 4.36). All this is achieved by the shirt having Bluetooth technology embedded in it, the signal being transmitted from a Java-enabled mobile phone. Sending a ‘hug’, actually a bit of HugMe™ Java-enabled software script, is just as easy as sending an SMS message. The shirt is washable and complies with latest Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) regulations for electronic equipment. Remote sensory experiences may seem rather an indulgence but given that contemporary work patterns often entail time away from loved ones, The Hug Shirt™ potentially offers some solace.

The Placebo Project by Antony Dunne and Fiona Raby

Invisible forces

Inextricably linked to our very visible world of electronics and ICT are the invisible electromagnetic fields created by these gadgets and systems. Design researchers and theorists, Antony Dunne and Fiona Raby at the Royal College of Art, London, refer to the radiating electromagnetic fields as a physical environment and call it ‘hertzian’ space.89 Their work, under the rubric of ‘critical design’, design that does not affirm the industrial agendas but challenges and questions it, focuses on the ‘interaction between devices, hertzian space and the imagination’.90 Their design is the opposite of the Hollywood blockbuster, it is Design Noir, fusing complex narratives in the context of everyday life. Critical design’s purpose is to ‘stimulate discussion and debate among designers, industry and the public about the aesthetic quality of our electronically mediated existence’91; it is not for the purpose of commercialization or exploitation by industry. In this sense it is not research and development but research and exploration, more closely allied to Walker’s propositional artefact (p83). It is concerned with the ‘lived experience not the medium’ which was aptly demonstrated in their experiment called the Placebo Project (Figure 4.37). Eight prototypes of semi-familiar domestic objects made of medium-density fibreboard (MDF) were given to individuals to introduce into their domestic environments who were later interviewed about their experiences with these objects. Electronic circuitry was embedded in some of the objects enabling specific functions as the electromagnetic fields from other electronic products in the home were encountered. Some objects did not have this capability. Each prototype was effectively a cultural probe92 providing an interface for learning about the lives of the individuals, the lives of the objects and their rich interactions. One of the more revealing facets of this study was the power of the ambiguity of the ‘placebo’ designs to stimulate the imagination of the users while simultaneously raising their awareness as to the invisible landscape and territories of electromagnetic radiation, a topic rarely touched upon in social discourse.

The Urban Farming Project by Dott 07

The purpose of Dunne and Raby’s experimental work was clear. Less easy to establish, as is common with much research-focused ‘design activism’, is how effective it was in communicating with and influencing its key audiences and its effectiveness in our transition to sustainable ways of living. The debate requires much wider currency to elicit positive transformative actions or for products to emerge in the marketplace or public domain.

Social cohesion and community building

‘Sustainable communities’ became a catchphrase for the New Labour government in the UK in the early 2000s,93 although defining a sustainable community remains problematic. Manfred Max-Neef’s framework for Universal Human-Scale Development94 attests to our genuine need for participatory, social and collective experiences, so the idea of using design to help generate improvements in social cohesion, to repair existing communities, or build new ones, seems to offer some promise. The ability for green interventions in the urban landscape to reconfigure and reorientate communities was positively demonstrated by the Home Zones project in 1996 in the Methleys neighbourhood of inner-city Leeds, in the north of England.95 A total of 800m2 of turf were laid for a weekend to given pedestrian priority to a busy urban street and host the Methleys Olympics. This story is embedded in the urban mythology of the area but even more importantly the event led to the official recognition of Methleys as a Home Zone by the local authority in 2002 – reward indeed to the champions in the local community, Heads Together, a creative agency, and architect Eddy Walker.

Catalysing positive social and environmental change is the founding premise of the Designs of the time 2007 (Dott 07) Project, an initiative funded by the UK’s Design Council and One NorthEast, in the north-east of England in 2007.96 Dott 07 was an exploration of how design could help society explore ‘what life in a sustainable region could be like’, through a year of community projects, events and exhibitions. The project focused on five aspects of daily life: movement, energy, school, health and food. One project that encouraged significant participation through design was Urban Farming (Figure 4.38). Consumer concerns over food miles, the carbon footprint or emissions, and contaminations with toxins coupled with the separation of food production from the city, has led UK planners and architects to ask how the urban landscape can be more ecologically productive and socially cohesive. Dott 07 enlisted a range of local partners in the project location, the town of Middlesbrough, with national partners with an interest in bio-regional systems of food production, and artist/blogger Debra Solomon who promotes food culture through Culiblog.97 In May 2007, containers of varying sizes (1m2 to 4m2) were delivered to locations across the town and more than 1000 people began producing fruit and vegetables culminating in a banquet for 1500 people in the town square in September 2007. The next phase of the project involves scaling up the operation by identifying new locations for urban farming. This task was completed by designers Andre Viljoen and Katrina Bohn, who have both investigated how urban landscapes can be more biologically productive and socially inclusive.98 The map generated represents a blueprint for a more sustainable local food economy. Other approaches to reexamining the ecological productivity of the urban or suburban landscape can be found in projects like Edible Estates,99 Edible Campus100 and the High Line Project in New York to utilize an abandoned elevated railway line for various landscape uses.101 Dott 07’s Urban Farming Project and other projects with ambitions to change our urban landscapes, clearly illustrate the catalytic potential of design to encourage communities to take action.

Activism finds expressions around a multitude of causes and issues (see Chapter 1, Figures 1.4–1.9) and activists will mobilize around emergent issues as they arise. The focus is on the present with a view to changing the near future. However, there are a handful of design activists who demand that we pause to examine rather more different timeframes. Long-term horizons are invoked by the sustainability debate but rarely given form or substance.

Time and design

These activists are mavericks by the very nature of their philosophical real-life manifestations. Here, the use of the word philosophical is applied in the old Greek sense of a way of living a life through practical realizations. They use profound design principles built on the disciplines of architecture, science and engineering, although they may not describe themselves as designers. Louis Le Roy’s Ecocathedral near Mildam in the Netherlands contests our very notion of man-made works and their explicit man-defined design lives102 (Figure 4.39). Le Roy’s hand-built monument of recycled brick and stone, constructed over 30 years, is just the beginning of a 1000-year project where time and space interweave in a mutually evolving, synergistic design.

Stewart Brand proposes a corrective project to deal with civilization’s dangerously short attention span.103 Brand’s Clock of the Long Now encourages long-term thinking; his clock is very big, very slow and is a strictly notional ‘instrument for thinking about time in a different way’.104 Founded in 1998, The Long Now Foundation is working on the practicalities of the clock and what it may mean to maintain something for 10,000 years. Lastly, we have the slow-burn project Roden Crater, the work of artist James Turrell, to turn an extinct crater in the Painted Desert, northern Arizona, US, into a place where the human spirit can seek a deeper relationship with the Earth and the universe through sensory synaesthesia and by being exposed to experiences whose depth is magnified by the manipulation of natural light.105 Famous for his ‘skyspaces’, Turrell has excavated inside the crater and created apertures through which the light of the sun, moon, distant planets, galaxies and even light beyond our galaxy (light that is 3.5 billion years old) can be experienced. In this place, examination of the word ‘sustainability’ takes an entirely new trajectory.

Activism Targeting the Under-consumers

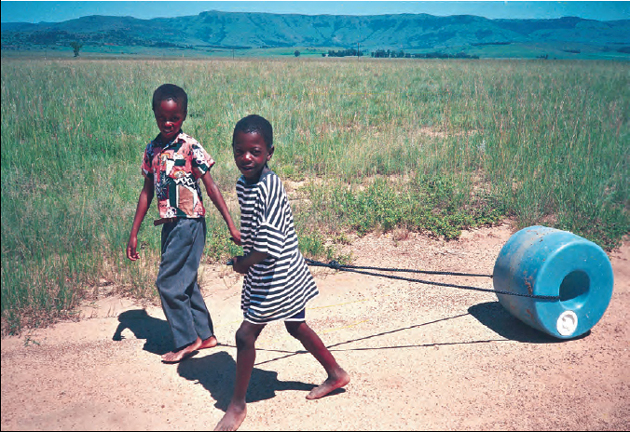

The ‘under-consumers’ may seem a strange term in a world where current levels of consumption seem unsustainable, the more so with the population due to increase to somewhere between 7.3 billion and 10.5 billion by 2050.106 The reality is that significant numbers of people go hungry every day, many do not have access to potable water, earn less than US$2 per day and/or live in temporary shelter (see Chapter 3, p55). These under-consumers exist in the affluent societies of the North as well as the societies of the South. Under these conditions, quality of life remains an abstract expression; these people are focused on survival, striving to meet basic physiological needs, permanently stuck on the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.107 These people actually need to have access to appropriate technologies and resources; they need to consume more resources. Resources may be available locally or regionally but unequal distribution and/or consumption of these resources by distant others able to pay a higher price, compounds local problems. A recent WWF report detailed the consumption of real and ‘virtual’ water for UK consumers.108 While the average UK consumer takes 150 litres a day from the water supply system, their ‘virtual’ water footprint (in food, textiles for clothing and other goods) is 30 times this amount, a total of 4645 litres per day per capita. This includes the water essential to food and other crop growth, plus water used in the manufacturing and processing industries. The latter is extensive as supermarket vegetables tend to be washed using very high volumes of water.109 One litre of water, sold in a PET plastic bottle can take up to nine litres of water in its production. A New Economics Foundation study in 2006 revealed the tentacles of the ‘UK plc’ supply chain feeding the UK’s high ecological footprint110 (see Figure 3.5). For the UK, this is about 5.8 global ha equivalent per capita (if shared around the world equably, the average footprint would be 1.8 global ha equivalent).111

Eco-cathedral by Louis Le Roy

Siyathemba by Swee Hong Ng, Architecture for Humanity

Depending on the various statistics that can be invoked, the ‘under-consumers’ represent between a sixth and a third of the global human population. Most of the design outputs addressing the under-consumers are predominantly ‘service artefacts’ (p85), services, and information and communication projects to raise awareness/education and/or provide new skills. Designs primarily focus on affordability, practicality, functionality and utility; other qualities, such as aesthetics, cultural fit and the generation of pleasure, are of secondary consideration and are often inadequately addressed. The drivers for this are diverse but may hint at a continuing underlying paternalism from the North, a lower order of priorities for this type of design, and lack of funds for designers keen to work with the underconsumers. Might there also be a lack of ambition by many designers to work in this arena? Papanek112 called upon designers to give just 10 per cent of their time to design for real needs. His clarion call seems worth reiterating today.

There are some positive signs that more designers are taking up the task of addressing their more global, as opposed to just commercial, responsibilities. In 1999, Architecture for Humanity (AfH) was established,113 out of which emerged the Open Architecture Network giving an opportunity for architects to donate design days to ongoing projects. In 2005, Denmark’s not-for-profit organization INDEX launched its Index: Design to Improve Life awards. Today INDEX is now operated and owned by the Danish Design Centre, Copenhagen, an original founding partner. These awards have undoubtedly helped call attention to and encouraged greater involvement of the global design community in targeting the over-consumers and the under-consumers.114 In 2007, a total of 337 design institutions nominated specific designs for the awards. Unfortunately, only a relatively small proportion of the designs of the nominated winners in 2007 would be affordable to those earning a few US dollars a day, and the cultural acceptability of some of the designs remains a moot point. A recent exhibition held at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, entitled ‘Design for the other 90%’, reveals varying standards of aesthetics, technology and production.115 In fact, some designs seem stuck in a time-warp, progressing little beyond the achievements illustrated in Papanek’s book 37 years ago. The conundrum expressed then is still valid today – how can we create useful, affordable, life-enhancing and beautiful design for the under-consumers? Nonetheless, all designers working to improve the lives of the under-consumers rightly deserve the moniker ‘design activists’, as they are genuinely intent on lifting people’s lives beyond a litany of daily tasks just to survive.

Shelter, water, food

Shelter

The provision of shelter for the needy reflects the stresses and strains evident on populations affected by economies that magnify the rich–poor divide, by global geopolitics and economics, by political regimes that result in inequality and persecution, and by disruptive man-made and natural disasters. AfH categorizes housing shelter driven by reasons of emergency, transition, permanence and homelessness, and addresses issues of community under ‘gathering spaces’ and ‘women specific places’.116 Tens of examples reveal inputs from international and local designers actively striving to meet the shelter needs of diverse populations. There always seems to be a delicate balance between imposed solutions from nonlocals and the enablement of local creativity, skills and desires. A project called Siyathemba provides an excellent example of getting the correct balance. Siyathemba, meaning ‘we hope’ in Zulu, originated as a community-driven project in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, to address the very high incidence of HIV/AIDS in young people. It is both a community shelter and point of healthcare (Figure 4.40). A competition was hosted by AfH in 2004, the brief being to design a youth care centre located and integral to a football/soccer field, the latter acting as a focal attraction to youth. Hundreds of designs were submitted by the international design community, were whittled down to a shortlist of nine and the winner chosen by young people in KwaZulu-Natal schools. The winner, designer Swee Hong Ng then travelled to the project collaborator’s Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies in rural Somkhele to refine the designs with local people. The resultant design provides Somkhele with a FIFA grade football pitch, a facility that combines healthcare services and football facilities and the first girls’ soccer league.

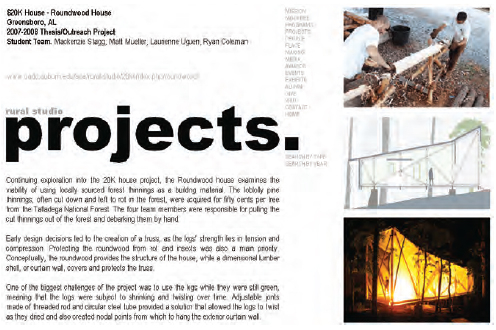

The US$20,000 house by Rural Studio graduates

The under-consumers in the US have received consistent attention from a variety of sources. Since its inception in 1993, Auburn University’s Rural Studio founded by Samuel Mockbee and D. K. Ruth has encouraged generations of students to work in collaboration with Alabama’s rural poor to improve housing stock and the wellbeing of its occupants.117 A recent project by graduates is the $20,000 house (Figure 4.41) offering a variety of configurations and aesthetics to meet real needs.

The diversity of needs of specific communities is being recognized by designers who create interventions, resources and concepts as a response. ParaSITE by Michael Rakowitz appropriates the waste heat/cooling from buildings’ heating/ventilation/air-conditioning (HVAC) systems by attaching inflatable structures that provide temporary accommodation for the homeless (Figure 4.42). One Small Project118 has multi-contributors that collate diverse solutions and creativity by slum dwellers to provide their own shelter. The Day Labor Station by Public Architecture examines the needs of the estimated 120,000 labourers that seek temporary day-by-day work119 and suggests a conceptual multi-functional space where labourers can up-skill and share peer-to-peer experiences.

Water and food