Activist Frameworks and

Tools: Nodes, Networks

and Technology

‘Imagine a better future. Find your allies. Share tools. Build it. Start now.’

Alex Steffan, Worldchanging1

People, People, People

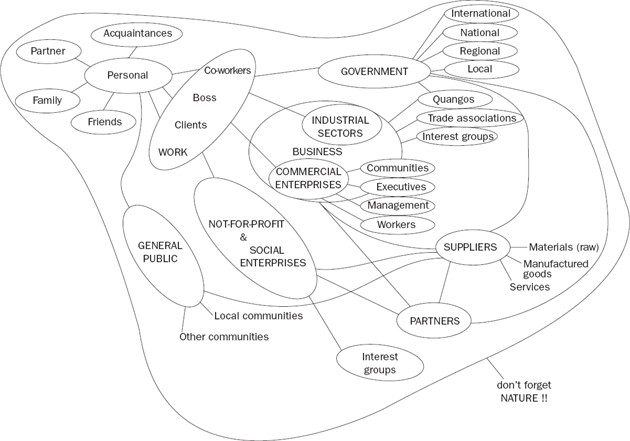

Activism is about motivating, activating and transforming people. This means connecting with people, using networks and organizing face-to-face meetings. It is also about the activists themselves, their motivations and intentions. A clear vision of the intention, purpose, strategies and goal of the activism, and the sustainability issues involved, will help identify the people that could contribute to the design process. One way to do this is to identify the primary, secondary and key actors and stakeholders (Figure 6.1). Here an actor is defined as a person or organization that will remain centre stage and is essential to the main storyline of the design project. A stakeholder is any person or organization that will have an effect on, and/or be affected by the design project. A stakeholder may or may not be an actor, depending upon their interests in the design project. An initial mapping of actors and stakeholders may evolve over the lifetime of the design project. Typically, stakeholder mapping in the business or commercial world is defined on an adversarial basis, i.e. those for and those against, and those who are neutral. This can be an additional layer of information added to the stakeholder map. Co-design processes are underlaid with strong participatory democratic principles encouraging equal representation, so positive and negative voices are seen as equally valuable because they help interrogate the problématique(s) more thoroughly.

Once the people are identified there is a broad array of techniques and technologies to bring them together and create a productive environment. The rise of the internet and Web 2.0 technologies, with the rapid expansion of hosted web services including social networking, video sharing, wikis, blogs and folksonomies,2 have enhanced our ability to communicate and coordinate with distributed networks. The rapid expansion of what is collectively called social software3 over the past few years offers a bewildering choice. Making an appropriate choice depends upon the intention and purpose of the (design) activist(s), the target audience and intended beneficiaries. The tools for connecting potential design collaborators may, or may not, be different from those used to help action the work and/or publicize it.

Figure 6.1

Identifying key actors and stakeholders

Whether old media or ‘new media’ are deployed to engage people, at some point people will need to get together. When this happens, how is this process facilitated to create maximum synergy and the best design outcomes/solutions? This section illustrates existing nodes, networks, technology and tools that help the design activist to be more strategically and practically focused. There is an a priori assumption that involving a wider range of people in the early appraisal of the problématique and early concept generation will tend to generate a more enabling design solution.

Toolbox for Online World

Existing design activism networks

The networks featured here are founded by and organized by designers. The complex demands of dealing with sustainability issues means that many design networks are multidisciplinary and/or experiment with emergent design approaches (Figure 6.2, Appendix 6). There are a significant number that gather around architecture for the poor (in the South and the North) and for disaster relief or general humanitarian work. A number of networks that have been around since the 1980s –Adbusters, Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility, Architects for Peace, and the O2 network4 – but many more have emerged over the past decade and some, such as The Designers Accord and Design Can Change, are very recently established.5 This indicates a resurgent interest from the design profession in local and global issues, and confirms a belief in the potential contribution that designers can make, and are already making, towards positive change.6

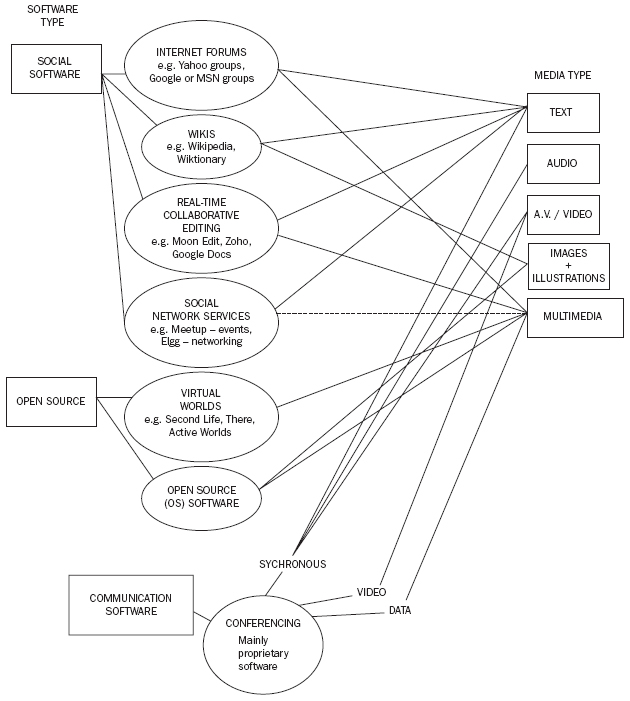

Distributed collaboration

Today the range of online collaboration options, beyond the ubiquitous email and telephone, is extensive and involves choices around the use of particular social, communications, and open source (OS) software (Figure 6.3). The ‘best fit’ choice depends on the task(s) in hand, the access to ICT and physical resources by the people involved, and their ability to use them. Although some of the dominant proprietary software brands are often the easiest option to use for a project, there is a diverse platform of OS software to help with setting up and running servers (e.g. Apache), operating systems (e.g. Linux) and applications (e.g. OpenOffice). These require some technical skill to set up but there are services to help with this task (e.g. Redhat, a commercial company, or Ubantu, a not-for-profit, for setting up Linux operating systems). Conferencing between multi-actors requires synchronous, video and/or data communications software. Most tends to be proprietary, although there are a few open source options.

Figure 6.2

Contemporary design activist networks

Figure 6.3

Tools for online collaboration for multi-actors

In terms of social software, internet forums, wikis and collaborative real-time text editors offer useful options for iterative discourse and text documentation. An internet forum, such as Yahoo, Google or MSN group, is an easy way of setting up an ‘interest’ group around a particular design project, while organizing social events can be carried out by notifying these groups, by regular email distribution lists or by using special social events organizing software like Meetup. Elgg is becoming a popular OS social networking software.

Collaboration in virtual worlds, such as Second Life, ActiveWorlds and There, is enabling new possibilities. In these worlds, users create a digital avatar by selecting various personal identity options (gender, clothing, hair style and so on). This avatar can wander around the virtual world landscape to meet and discourse with other avatars. Users create the virtual landscape themselves. Second Life, founded in 2003 by Linden Research,7 is perhaps the most interesting example because it is providing a vehicle for exchange of ideas and real money making (the currency in Second Life is the Linden dollar, having an exchange value in the order of 260–270 Linden dollars to US$1, at 2007 rates). Today there are more than 15 million registered ‘resident’ accounts with one avatar per resident, although the appearance of the avatar can change according to the whims of the account holder. Account holders who generate digital content in Second Life retain copyright and there is a permissions and digital rights management service for those who wish to copy content. Commercial companies are experimenting with collaborative design in Second Life, with staff from Philips and Fiat reputedly having engaged in ‘crowdsourcing’ (see below) and other collaborations to imagine new products and services. This is a form of open innovation tapping into widely distributed knowledge, potentially useful for commercial and educational possibilities. A recent survey revealed that 80 per cent of UK universities have used Second Life for teaching purposes.8

Other companies have set up their own platforms for extending collaboration beyond traditional research and development (e.g. IBM set up its Eclipse platform), although the boundary between open innovation, where IP is licensed or shared under agreement, and open source, and the potential to beneficiaries, is the subject of ongoing debate.

Various mass collaboration experiments are occurring through the distributed networks and communities of the internet using social, communications and open source software.9 Crowdsourcing involves the engagement of large numbers of people in a task traditionally performed within a company or its supply chain.10 It is invoked and controlled by commercial interests, but nonetheless represents an emergent approach to co-creation and co-design. Organizations can now also use Amazon Mechanical Turk to coordinate crowdsourcing tasks. Successful crowdsourcing initiatives range from internet-based retailing of t-shirts (Threadless) to compilation of data for buildings/builders (Emporis) and even predictive prospecting for a gold mine company (Goldcorp).

Recognizing the power of the crowd, a number of proprietary services have emerged to join together inventors, designers and other partners. These include companies such as CrowdSpirit and Kluster which function as ideas banks within which members can participate in core product development teams and explore the commercial potentiality of ideas. Alternatively, it is possible to take a problem to an open innovation service, like Innocentive, to engage brainpower beyond the normal reach of an R & D department or design agency.11 Japanese designer Kohei Nishiyama, of Elephant Design, Tokyo, is targeting design agencies to submit their prototypes to his web interface and consumers can get involved in finalizing the design process with what he calls, Design to Order.12 Once enough ‘votes’ are received, then a prototype product moves towards being manufactured. Nishiyama is currently testing a trial site for retailer Muji to help develop products for its stores.

Potentially more anarchistic methods of online collaboration involve the act of ‘flash mobbing’, the coordination of a group of people through internet and mobile telephony systems to quickly assemble in a public place for an event or happening and equally quickly to disperse. Flash mobs are a particular kind of ‘smart mob’, a term coined by Howard Rheingold in 200213 to describe a self-structuring social organization displaying intelligent emergent behaviour that communicates through technology-mediated channels (internet and various wireless devices – laptops, mobile phones, PDAs). The potency of smart mobs is being utilized by everyone from anti-global and anti-capitalist protestors to consumers organizing mass shopping events to level discounts from retailers. Its potential to engage people in designing for positive change remains largely unexplored, although well-known brands such as eBay and Amazon, and phenomena such as internet social tagging, all utilize smart mob thinking in their modus operandi.

Ways of sharing visualizations

Most designers communicate through a wide range of visualization tools using proprietary software to explore concepts, develop scenarios and specify detailed design. In today’s networked world, the sharing of multimedia files is a necessity for the modern design agency and involves a considerable skill set. This represents quite a challenge when working with non-designers, the general public and clients. Aside from the proprietary multimedia file formats and software applications there are some straightforward ‘entry level’ visualization tools, although professional designers may not find them to be very sophisticated. Google introduced SketchUp to make it easier for everyone to create and share 3D models.14 While this is basic 3D modelling software, it has some potentiality for people to digitally visualize the built environment and has even recently been adopted by an architect, Michelle Kaufmann, promoting eco-housing.15 There are various open source applications that offer simple 3D visualizations for objects and illustrations (e.g. Wings 3D), very basic sketching (e.g. RateMyDrawings, ImaginationEmbed) and for synchronous whiteboard sessions (e.g. Groupboard). More sophisticated yet easy-to-use visualization tools seem to be needed, so there is a potential gap in the market here.

Certain networks are encouraging the sharing of designers’ visualizations. For example, by September 2008 the Open Architecture Network (OAN)16 had attracted more than 12,500 members in just 18 months and displayed plans, drawings and renderings for 1149 projects ranging from disaster housing to shelter for the poor and marginalized. Subject to certain terms, these designs can be used and adapted for other projects.

Ways of making

The entrepreneurial spirit of the internet is challenging how we make things. This is happening in both mass and niche markets. Various permutations of electronic mass customization are offered by manufacturers. In this context, mass customization means being able to manufacture a product or service to meet a customer’s needs with the concurrent efficiencies and gains expected of mass production. Many personal computer manufacturers offer a service that enables customers to tailor the specification of the computer to their personal or business needs – this is what Pine termed ‘collaborative customization’17 as distinct from adaptive customization, when the end-user later alters or changes the product themselves. At the other end of the scale, from a consumer-led perspective, it is now possible for end-users to design their own t-shirts and have a one-off or short print run made.

Designers are also testing emergent ways of designing and making. An outreach programme called FabLabs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, led by Neil Gershenfeld at the Center for Bits and Atoms, is investigating the application of 2D and 3D tools in integrated manufacturing centres, to fabricate components using designs delivered digitally to a bank of local machines.18 The machines include a suite of software applications linked to routers, laser cutters, 3D printers, moulding and casting and circuit-making machines. FabLabs can be adapted to specific prototyping or small batch manufacturing tasks.

The possibilities of distributed manufacturing are being investigated by other designers and engineers. Adrian Bowyer and Vik Oliver of Bath University, UK, have, since the inception of the concept in 2004, successfully developed a rapid prototyping machine that can replicate itself, called RepRap – Replicating Rapid-Prototyper (see Figure 4.18, page 104).19 Material costs for the RepRap are a modest £400 and the open source designs are available under a GNU General Public License. Freedom of Creation in Helsinki, Finland, use a process of laser sintering to create rapid manufactured textiles that can be downloaded to be locally manufactured, preferably at a local CNC router shop. These developments potentially herald a new dawn for distributed manufacturing of certain types of products. Downloading digital designs and making them locally remains a potential revenue stream waiting to be further explored.

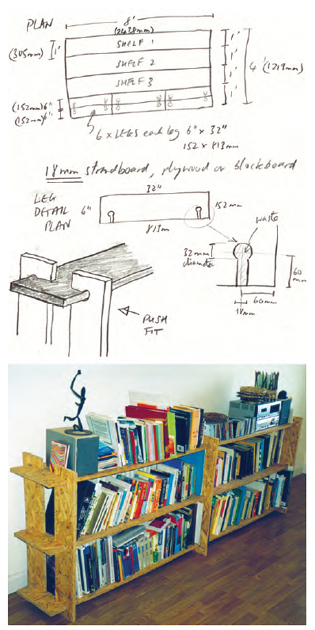

In a more prosaic but very effective approach, designers are offering simple cutting plans to enable people to make their own artefacts. In 2003 Tempo, a student-led sustainable design network in Cornwall, UK, led a project called ‘8 × 4’, to create furniture with minimal wastage from standard 8 × 4ft OSB board or ply sheets using only basic tools (Figure 6.4). Cutting patterns for furniture, toys and games are emerging, and no doubt many more will follow as designers (professional and amateur) sell and/or donate designs enabling people to ‘make-it-yourself.20

Ambitious open source design-and-make projects, often involving large numbers of designers, include the world’s first OS hydrogen car, the c,mm,n,21 launched at Amsterdam’s AutoRAI show in February 2007 (see Figure 4.28, page 111). This joint project between the Netherlands Society for Nature and the Environment, the Technical University of Delft, (TUDelft), University of Eindhoven and University of Enschede, is a zero-emissions vehicle whose technical drawings and blueprints are available online. Other open source car designers include the Society for Sustainable Mobility which is looking to develop a very economical SUV that is designed collaboratively but certain rights are retained to attract potential manufacturing investment.22

Open source mapping of cities’ green consumer outlets, facilities and spaces has been encouraged by a not-for-profit organization called Green Maps, in New York.23 Green Maps provides a basic set of universal icons to represent the different ‘green’ elements within a city, town or location, and a toolbox to help users set up their own map. These can be adopted, modified and new icons added to build up a local and cultural flavour to each map. There are now hundreds of maps in more than 50 countries.

Toolbox for Real World

The main sources of inspiration for collaborative, participatory design come from on-the-ground community-based or community-inspired projects. There is a healthy history of participation through community architecture,24 action/collaborative planning25 and more grassroots activities such as the lived experiences of communities creating their own eco-villages26 and the Slow Food movement.27 New fields of endeavour are emerging in response to a growing sense of environmental and social crisis. For example, the local activist movements Transition Towns are dealing with a post-peak oil future and ‘powering-down’ off oil dependence.28 The community, or at least the idea of a community and it being rooted in a real place, provides a focus. This is more problematic when considering consumer products or services, which tend to be more highly distributed and commercially orientated.

8 × 4 Tempo project

Typically, products and services are considered in smaller groups in a more design-led environment. This section examines the range of real-world options for designers wishing to pursue a more co-design or participatory design approach.

Selecting the right kind of co-design event

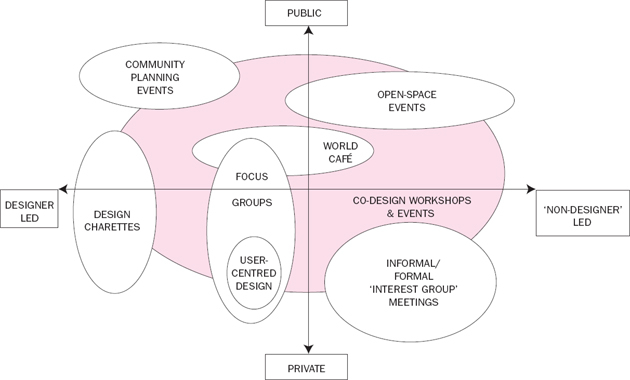

The right choice of co-design event depends upon the purpose and goal of the design activism, and the intended target audience and beneficiaries. Considerations need to be given to whether the event is designer-led or led by ‘non-designers’, whether it is public or private, and the size of the event (Figure 6.5, Table 6.1). Community planning and open space events are fine for large numbers of people including a mix of experts, professionals and lay people. These events are well suited to planning or built environment projects. Moderate numbers are suitable for events such as World Café, co-design workshops or design charettes. Small groups or numbers are better for informal/formal ‘interest’ and ‘focus’ group work.

Deciding the ‘best fit’ event for your particular kind of design activism means matching your purpose against the ‘designed’ purpose of the event. Do you want a formal or informal event? Some events require that the design context is set in some detail prior to the event, others are more open questions intended to help define the design context by means of collective intelligence. A key question is whether an existing design context needs refining or whether there needs to be a full dialogic discourse about the very nature of the design context.

Informal meetings of interest groups do not have a particular format or plan. A successful example of this type of group is Green Drinks, initiated by Edwin Datchefski of Biothinking in 1999.29 There are more than 350 chapters of Green Drinks worldwide who meet to discuss and network around topical and local environmental issues.

Whatever event is chosen it is likely that its success will depend upon good planning, communication, facilitation, application of appropriate tools and techniques, information capture, dissemination of results, and some form of measurement of action on the ground.

Planning, inspiring, leading and facilitating

Planning is the foundation to all co-design events. Typically, it is important to give consideration to the questions listed in Table 6.2. An appropriate structure for the event including designated people to help control the schedule, flow and communication, will lead to a more successful event. This may include all or one of the following people: a chair, a facilitator(s), an organizing team and a panel of specialists or experts. Small-scale events may only need a facilitator. There is a huge array of techniques that can be deployed by these designated people.30 The work of a facilitator is most important and usually revolves around some basic principles:

- inclusion – getting everyone to voice their opinions

- listening – getting everyone to listen ‘deeply’, i.e. to the surface and underlying messages

- communicating, capturing and disseminating information during the event

- allowing adequate time for tasks

- applying the most appropriate tools for the tasks and

- summing up and pointing to the next steps.

Co-design events, designer-led to non-designer-led

Selecting the right co-design event

Ideal number | Type of co-design | Purpose of event | How is design context |

| Large | Community planning events and design charettes Open space events | Exploring the views of a wide range of actors and stakeholders by encouraging them to participate in the planning process Engaging large groups in discussions to explore key questions or issues | Around a proposed development Around a topical question or issue framed by the title of the event |

| Moderate | World Café Co-design workshops or small-group design charettes | Exploring specific questions with invited actors and stakeholders Explore the problématique around a particular design context with a view to generating a design brief, process and/or outcomes | Around a specific topic framed by the organizers of the event Around a specific design context framed by the organizers of the event |

| Small | Informal/formal ‘interest’ groups Focus groups | Exploring particular issues and resolving strategies, actions and ways forward Exploring the opinions and views of specific actors and/or stakeholders and/or users invited by the organizers | Around the specific issues defined by the ‘interest group’ Around an existing/ proposed development, or prototype product or service |

Planning for a co-design event

The coordinators |

| Coordinating individual and/or organization? |

| Any associated individuals or organizations/organizers? e.g. administration, technical, professional or expert inputs? |

| Need for a chair, facilitator and/or panel? |

The nature of the event |

| Reason and purpose of the event? |

| Goal(s) for the event? |

| Which participants? Actors? Stakeholders? Experts? Professionals? Others? |

| Type of event? |

The practicalities |

| Location and venue? Where? |

| Timing? When, why? Lead time for planning? |

| Costs? Prior to, at and after the event? |

| Funding sources? |

| Other considerations? |

The Multi-Stakeholder Processes Resource Portal, the Netherlands, has a diverse range of tools, methodologies and facilitation resources to enable more effective participation for multi-stakeholder situations.31

With the appropriate structure in place it is often useful for a keynote speaker, expert, chair or facilitator to frame the context, give some detail and engage the audience in the task ahead, before commencing participatory work. Audiovisual inspiration is critical at this juncture to get the participants involved. Grassroots organizations, such as Transition Towns, give particular advice on running Open Space and World Café type events.32 Where groups are moderate or smaller it is useful to form the audience in a circle or gather them around tables and for the facilitator to encourage people to briefly introduce themselves in a ‘go round’. The more that the event locale and schedule can be configured to maximize an equal input from different voices, the better the outputs will be.

Event techniques (methods, tools, games)

It is important to choose the correct technique for the appropriate part of the cycle of a co-design event. There may be several phases to the event after preliminary introductions and context setting – these can involve exploring, analysing and deciding (Figure 6.6). Exploring is a key part of the early stages of the co-design process and should involve text- and visual-based tools and outputs where possible.

The author finds the application of the ‘word circle’ technique useful in the early stages of a workshop, but it can be appropriate at any time to help participants establish the key concerns or focal points. It is best utilized for smaller groups, between 5 and 15–20 people, but larger groups can be subdivided. Each member of the group is allowed to articulate one word, or phrase of two/three words, about a defined subject area during the workshop (this can be an issue, about understandings or framings of the design context, about a particular development, or artefact, and so on). Each participant’s word is captured by the facilitator in a large circle on a flipchart or white/blackboard. Then each participant is asked to join up any two of the circles containing words, using a marker pen/chalk, with a straight line. One participant has one line. When all the participants have marked their line, the facilitator then highlights the words with the most lines, the words that frequently couple and the words that are not as popular. A ‘go round’ is used for everyone to articulate their thoughts about the word circle (see Figure 5.6 for an example of a word circle from a ‘slow design’ workshop). Word circles encourage participation, give everyone a ‘voice’, help delineate synergetic and divergent views and, most importantly, create a sense of collective and individual ‘ownership’ of the ideas expressed. This tends to elicit better collaboration and co-operation.

Methods and tools to help facilitate a co-design workshop

Mind-mapping, card techniques (Delphi techniques, metaplanning – use of cards or Post-it notes to group or cluster information, questions and/or issues) and so on, help with the task of gathering and communicating diverse points of view from the participants. Once the key issues have been articulated, summarized and absorbed, then the design context can be given more definition and the participants can move on to further explorations using more visually stimulating tools which help develop stories and scenarios. Typical techniques may involve brainstorming by drawing, using games to stimulate ideas and drawings (e.g. Play ReThink), story-boarding and scenario sketching, the use of proprietary cards that assist with scenario development and understanding actor/user/stakeholder needs (e.g. IDEO cards; Flowmaker cards).

On the ground and active

Towards the end of a co-design event, the chair, facilitator and/or organizers should summarize what happened at the event, what was expressed, what was learnt, what agreements and disagreements exist, and what actions should be taken next (and by whom). This is the most difficult phase of any co-design event as it is easy to gather participants around a topic/issue/design context, feasible to get them to generate ideas and work on concept solutions, but hard to turn words into action. Most of the advice seems to centre around:

- keeping the actions simple, focused on the vision or big idea (and checking that everyone gets the big idea)

- making sure that the relevant people know what is expected of them next

- ensuring adequate communication and networking systems exist to get it all going on the ground and

- setting a follow-on event to track progress and receive feedback to check if it is all heading in the required direction to reach the visionary goal.

At some point, the design activists should try and assess the effectiveness of the strategies, tools and methods applied to reach their goal (refer to Table 4.3). Feedback is essential to readjust the evolving participatory design process or to simply congratulate the participants on having achieved what they (and the design activists) set out to do.

Notes

1 Steffan, A. (ed) (2006) Worldchanging: A User’s Guide for the 21st Century, Abrams, New York, p536.

2 ‘Folksonomies’ denote ways for collaborative tagging, social classification, social indexing and social tagging in order to mark something as being popular or as having received confirmation of popular validity.

3 ‘Social software’ enables the sharing of data and interactions using a range of software applications.

4 Adbusters, www.adbusters.org/; Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility, www.adpsr.org/Home; Architects for Peace, www.architectsforpeace.org/index.php; and the O2 network, www.o2nyc.org/, New York, US.

5 Designers Accord, www.designersaccord.org/; and Design Can Change, www.designcanchange.org/#home

6 See more examples of design in the cause of activism, Steffan (2006), op. cit. Note 1; Sinclair, C, Stohr, K. and Architecture for Humanity (2006) Design Like You Give a Damn: Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises, Thames & Hudson, London.

7 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Second Life’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Life

8 Ibid.

9 Tapscott, D. and Williams, A. D. (2007) Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything, Atlantic Books, London; Leadbeater, C. (2008) We Think: Mass Innovation, Not Mass Production, Profile Books, London.

10 Wikipedia (2008) ‘Crowdsourcing’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crowdsourcing

11 Innocentive, www.innocentive.com/

12 Sample, I. (2007) ‘The future of design? Voters pick the next must-have on the net’, The Guardian, 24 November 2007, p11.

13 Rheingold, H. (2002) Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution, Perseus Books, New York.

14 Google SketchUp, http://sketchup.google.com/

15 Michelle Kaufmann Designs, http://sketchup.google.com/green/mkd.html

16 Open Architecture Network, www.openarchitecturenetwork.org/

17 Pine, J. (1999) Mass Customization: The New Frontier in Business Competition, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA; originally published 1992.

18 MIT FabLabs, http://fab.cba.mit.edu/

19 RepRap, http://reprap.org/bin/view/Main/WebHome

20 See for example, Kith-Kin, www.kith-kin.co.uk/home.asp; Instructables, www.instructables.com/

21 c,mm,n open source car design, www.cmmn.org

22 Leadbeater (2008), op. cit. Note 9, p135.

23 Green Maps, www.greenmap.org/

24 Bell, B. (2004) Good Deeds, Good Design: Community Service through Architecture, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

25 Wates, N. (ed) (2008) The Community Planning Event Manual, Earthscan, London.

26 Global Ecovillage Network, http://gen.ecovillage.org/

27 Petrini, C. (2007) Slow Food Nation: Why Our Food Should Be Good, Clean and Fair, Rizzoli, New York.

28 Hopkins, R. (2008) The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience, Green Books, Totnes; Transition Towns, www.transitiontowns.org

29 Biothinking, www.biothinking.com; Wikipedia (2008) ‘Green drinks’, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Drinks

30 See for example, Chambers, R. (2002) Participatory Workshops: A Source Book of 21 Sets of Ideas and Activities, Earthscan, London.

31 MSP Resource Portal, http://portals.wi.wur.nl/MSP/?page=1180

32 Hopkins (2008), op. cit. Note 28, refer to ‘Open Space’, pp168–169 and ‘World Café’, pp184–186.