Up to this point, this book has focused on the individual elements that make up a well-lit shot. We have discussed character lighting and point lights and compositing and RGB mattes as separate elements. In reality, these elements do not work in isolation but instead in coordination with one another to create an overall look. In this chapter, the goal is to focus on successful shots in animated films and how each utilized the techniques discussed in previous chapters to create beautiful images.

Figure 8.1 Still from the animated short Premier Automne. Property of Carlos DeCarvalho.

Figure 8.2 Still from the animated short Little Freak. Property of Edwin Schaap.

Figure 8.3 Still from the animated short Shave It. Property of 3DAR.

Figure 8.4 Still from the animated short The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore. Property of Moonbot Studios.

Figure 8.5 Still from the animated short Edmond était un âne (Edmond was a Donkey). Property of Papy3d/ONF NFB/ARTE.

Figure 8.6 Images from Cicada Princess used by permission courtesy of Mauricio Baiocchi ©2014 Mauricio Baiocchi. Portions © Steven Ferrara. Lighting Artist Yun Shin.

Figure 8.7 Still from the animated short L3.0. Property of Pierre Jury, Vincent Defour, Cyril Declercq, Alexis Decelle, and ISART DIGITAL (school).

Figure 8.8 Still from the animated short Mac and Cheese. Property of Colorbleed Animation Studio.

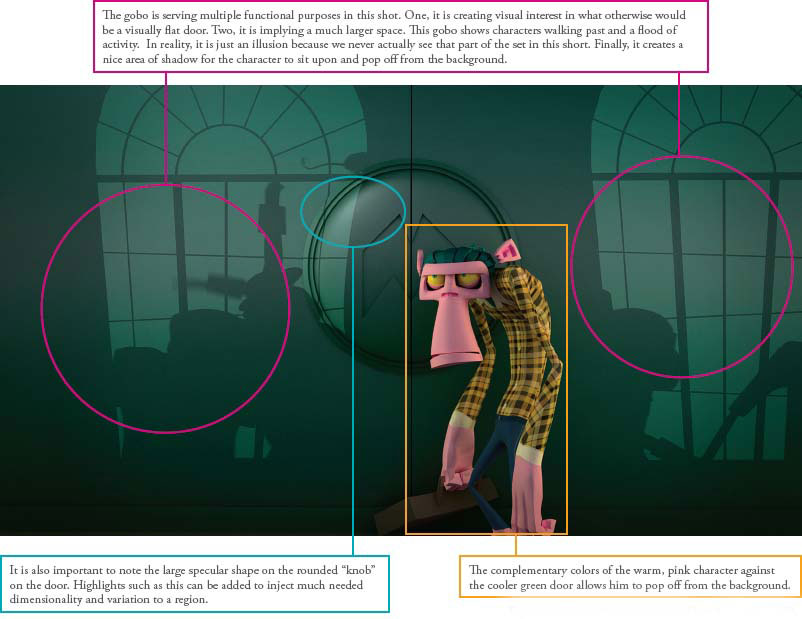

Figure 8.9 © 2010 Ubisoft Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Raving Rabbids Travel In Time, Ubisoft and the Ubisoft logo are trademarks of Ubisoft Entertainment in the U.S. and/or other countries. Trailer produced by Akama. All other rights are reserved by Ubisoft Entertainment.

|

Q. What is your current job/role at your company?

A. I am currently a CG Supervisor at DreamWorks Animation. I am responsible for delivering full film sequences through surfacing, lighting, compositing, paint fix, and finally to luster. I manage mid-to large-size teams of lighting artists and technical directors. I show these movie sequences to the VFX supervisor, production designer, art director, director, and finally the executive studio management before it goes to film.

Q. What inspired you to become an artist on CG films?

A. I have always been a fan of animation and VFX from childhood. Since I could hold a pencil, I have also always been a painter and very much involved in the arts. I have worked in all mediums from chalk, oil paints, to spray paint while doing graffiti murals … I grew up in NYC so it was very much a part of my culture. But after college I needed to work and find a way to make steady money. Painting murals and selling my work really didn’t appeal to me as I wanted to keep all of it to myself and not sell anything. I started on my current path in magazine graphics learning image manipulation using programs like Photoshop and After Effects on old Macintosh clones. That became a bit boring and repetitive technically and it failed to really challenge me. I eventually decided to get a Masters of Fine Art from SVA in NYC to really learn 3D/motion graphics/film making. After that I worked in advertising and video game cinematics for a few years at various places like R/GA and Blur. But really, what I wanted to do was the high-end feature films because of how large-scale and polished they are. Eventually my reel became good enough for DreamWorks and they moved me to San Francisco to light for Shrek 2.

Q. What non-CG artwork inspires you?

A. I grew up blocks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the MOMA so there are literally thousands of paintings, photos, and sculptures that move me. I was a huge fan of Red Groomes after seeing his piece Ruckus Manhattan … which was a large-scale paper maché version of Manhattan in the 70s. I also love Rembrandt and any artist who really tries to capture light. Basically, all of the artists in the Hudson Valley School, and most Impressionists. My paintings and artwork always were a study in lighting of some kind or another. It made sense that my professional life focused on this too. I could go on for hours about art and lighting. It’s what motivates all the decisions I have made to get to this job and the images I make doing this job.

Q. Can you talk us through your process of critiquing an image for its positives and negatives?

A. Generally it’s always a case-by-case basis. Ask yourself, “What’s the point of the shot or sequence or frame?” If it’s a specific mood then you can go with the usual color choices. Cool tones for calmness, depression, sadness, seriousness. Warm tones for anger, conflict, or even comfort if the warmth is not too red. General rule of thumb for feature film lighting is to be sure you are helping the story out. Are you putting emphasis to the action or character? Are you de-emphasizing areas that aren’t important? You also have to make sure you aren’t being too complex or distracting. Most of the time the director wants the film to be pretty but his/her real interest is the story they are trying to tell. Really good lighting is the kind of lighting you don’t notice.

Q. Visually, what is the most important element in a successful image for an animated film?

A. The story is the most important element. The lighting has to tell the story, it has to help the moment get conveyed to the audience. A successfully lit frame shouldn’t scream “Look at the pretty lighting!!!” It should of course be pretty, but it shouldn’t have a presence so the audience stops to look at it instead of following the story of the film. It should fit perfectly into the moment so as to almost go unnoticed. Remember that most directors are storytellers and not artists. Their job is to tell the story without too much distraction. Audiences are also not usually so tuned into the nuances of light and color as their emotions are. They also want to like or hate the characters, they want to understand the action. All too often lighting and action can hinder this in that they try too hard to make everything beautiful. If you light and color an element in the background so dramatically and beautifully, you can actually harm the film when the audience ends up looking in the wrong part of the frame and missing the acting or the action. But don’t get me wrong, light all those elements as well as you can, but when compositing use depth of field and make sure the attention and focus of the image will always be where it needs to be. These images fly by at 1/24th or 1/48th of a second and people need to be told where and what to look at without hesitation.

Q. What do you think is lighting’s largest contribution to an animated film?

A. I think it’s one of the most important parts of a film that people are unaware of. Most people won’t even think about it, especially if it’s done right. But … when they are in the moment, looking at beautiful colorful and sometimes photo-realistic images, and they really feel it’s real … and they are in the moment … that’s when lighting is truly contributing to the film. Fans will speak of their favorite characters, and their favorite plot twists, but what they see in their minds is actually the lighting. What they remember most vividly is the rich images that the movie takes place within. Lighting doesn’t get the fame and the glory, there isn’t even an award for lighting at the Annie Awards … but imagine if these movies weren’t lit? Have you ever watched a film pre-lighting? Shaded simply by OpenGL shaders? It’s hard to know what to look at. Nothing looks real, and it doesn’t have any shape to it that makes physical sense. It’s hard to know how to feel. It is very much missing the flavor of the final lighting images. What lighting adds to the film is immeasurable and is hard to quantify. A film without lighting is like corn flakes without the milk.

Q. Where do you think the future of lighting is headed?

A. Lighting has always been headed to photo-realism in both animation and VFX. Every software innovation since the beginning has been to harness the ever growing power of the processor to fake what happens to light in real life. When I started we had to fake bounce lighting with point lights, and soft shadows of any kind were super expensive. Now we have global illumination, radiosity, gathering, and occlusion as normal tools, even for the single computer user at home on a PC. MCRT renderers like Arnold are bringing physically based rendering to small shops and taking a lot of the labor out of lighting and allowing artists to spend their newfound time to polish and make real artistic decisions. I think like all things it’s slowly taking the labor out of the task … but that being said, lighting will never be fully automated for storytelling. Just because it is getting easier to make things look pretty and real doesn’t mean an artist isn’t needed to manipulate that real lighting to fit the composition or story or mood of the film. Even though MCRT makes soft ray-traced shadows and bounce lighting out of the box doesn’t mean directors want what’s accurate. They will want artistic manipulation and choices to be made to further the story they are telling. They will want stylized looks and maybe even intentionally not realistic-looking images. Lighting is an art and a necessity to filmmaking.

Q. If you could tell yourself one piece of advice when you were first starting out in this industry, what would it be?

A. Try a little bit of everything before making big decisions. I was a generalist at first and I think it was a good move since I know how to do everything from modeling, animation, FX, lighting, surfacing, and compositing … even editing and storyboarding. I would tell myself not to make a hard decision about narrowing it down to join a big studio too soon. I made a thesis in school but I should have done more on my own. I feel that once you join the workforce, you lose that ability to make something totally your own. That’s the sweet spot of animation. Doing it for yourself.

Q. In your opinion, what makes a good lighting artist?

A. I used to think it was talent and ability combined. There are people who are just amazing at making images and lighting, and there are people who are amazingly good at the software. Then there are sometimes people who can do both. Those who are good at both were considered the best to me. But, now that I manage and direct a team of them, I can say it’s more nuanced than that. Really good lighting artists often know it. They can be hard to work with due to ego and sometimes they take a lot of managing because they refuse to work with a team, or to light appropriately to the story or point of the shot/sequence they are working on. A truly good lighting artist has ability and knowhow, but also sees the bigger picture of the animation. They are a storyteller and their lighting works to the greater good of the story instead of showing off their lighting skills individually.