CHAPTER 1

Understanding Channels

Channels Don’t Exist in Isolation

Channels Reflect Interactions, Information, and Context

Changing the Channel-Centric Mindset

The concept of channels pervades the modern business organization—for example, channel team, channel strategies, cross-channel, multichannel, omnichannel, channel preference, channel ownership, and on and on. Ideally, channels create connections to communicate and interact among people. However, they can also become silos that separate and create barriers between people, teams, and priorities.

From Theory to Reality

In the classic sense, a channel is a construct through which information is conveyed, similar to a waterway. Just as the Panama Canal delivers ships and cargo from one ocean to another, a communication channel connects the information sender with the information receiver.

In the world of designing services, a channel is a medium of interaction with customers or users (see Figure 1.1). Common channels include physical stores, call centers (phone), email, direct mail, web, and mobile (see Table 1.1). Behind these channels sit people, processes, and technologies. Channel owners count on these resources to reach their customers, deliver value, and differentiate them from their competition.

In addition, these channel owners are often evaluated and rewarded on the success of their individual channel metrics, which can be a detriment to connecting channels across an organization.

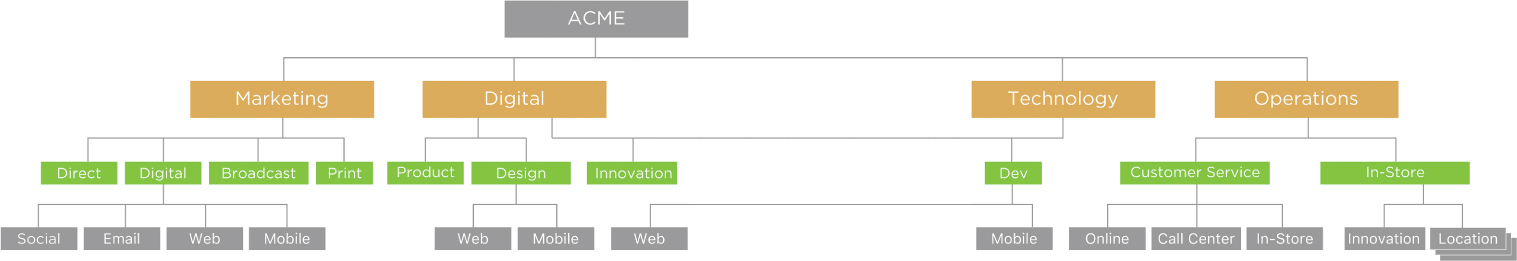

FIGURE 1.1

Understanding and aligning with others on your channels is a foundational step toward orchestrating experiences.

TABLE 1.1 COMMON CHANNELS

Physical Store |

Digital |

Customer Service |

Marketing |

Signage |

Web |

Call Center |

Broadcast |

Kiosk |

Mobile |

IVR |

|

In-Store Screens |

Mobile Web |

Live Chat |

|

Environmental Displays |

Native App Live Chat SMS/Messaging |

Chat Bots |

Direct Mail Digital Marketing Social Media SMS/Messaging |

Designing end-to-end experiences necessitates stepping into these channel-org dynamics. As an orchestrator, you need to understand how deeply engrained channel thinking (vertical ownership) can deter innovation and value creation. Your objective is to reframe channels as coordinated role players in the greater story of serving customers’ journeys (horizontal servitude). The following four concepts will arm you to take on this challenge:

• Organizations are structured by channels.

• Channels don’t exist in isolation.

• Channels are defined by interaction, information, and context.

• Channels should support the moment.

Structured by Channels

All companies start somewhere to market, deliver, and support their products and services to customers. For example, Lowe’s Home Improvement started as a small storefront in a small town. Sears sold watches by mail order catalogs. UPS distributed paper forms filled out in triplicate to pick up, transfer, and deliver packages accurately. Netflix sent discs by mail. Amazon sold books on the web.

Over time, companies adapt and expand to engage with customers in new ways and new channels. Take Lowe’s Home Improvement, a U.S. retailer, as an example. For decades, Lowe’s primarily interacted with its customers through hundreds of retail stores and thousands of associates supported by television, radio, newspaper, outdoor and direct mail marketing, and advertising. In the 1990s, Lowe’s (and its competitors) began moving into the digital realm both online and in the store. Now, two decades later, Lowe’s has an expansive digital footprint including websites, apps, kiosks, associate tablets, and even a wayfinding robot (see Figure 1.2) that exists alongside the same channels that Lowe’s has operated in from the first day it opened its doors. Lowe’s answers customer questions through online chat, Twitter, in store aisles, and on the phone. It promotes sales on radio, via Google AdWords, in direct mail, and on physical and digital receipts. It teaches how to do home improvement projects in workshops, on YouTube, and in iPad magazines. That’s a lot of channels.

PRESS RELEASE PHOTO FROM: HTTPS://NEWSROOM.LOWES.COM/NEWS-RELEASES/LOWESINTRODUCESLOWEBOT-THENEXTGENERATIONROBOTTOENHANCETHEHOMEIMPROVEMENTSHOPPINGEXPERIENCEINTHEBAYAREA-2/

FIGURE 1.2

LoweBot, developed by Lowe’s Innovation Labs, opens a new channel to help customers find products in the store while also tracking and managing inventory.

Lowe’s went online. Sears opened retail stores. UPS put digital tablets in its associates’ hands and self-service websites in its customers’ browsers. Netflix shifted to streaming. Amazon now sends their own delivery drivers (and drones!) to bring items to your door. Over time, organizations determine which channels to invest more or less in to meet their business objectives and connect with the evolving needs and behaviors of their target customers.

A good example of this evolutionary pattern can be seen in marketing. As the number of communication channels expanded in the last century, marketing groups (and their external agencies) formed teams to own newer channels, such as web, email, search engines, social media, and mobile. A typical marketing campaign, as a result, requires a lot of coordination. Multiple channel experts must align around a common strategy, the channel mix for tactics, and a plan on how to get all the right messages to all the right people at exactly the right time. Then they must coordinate with internal and external partners to define, design, and develop customer touchpoints for their channel.

That’s a lot of people and a lot of coordination, and marketing is only one group among many looking to leverage the same channels to deliver value to customers.

These dynamics have only accelerated over the past 30 years as new digital channels—web, email, mobile, virtual reality, and so forth—have emerged as new ways to communicate, interact, and deliver products and services. The bright and shiny digital world often overshadows older media and channels. Yet, companies still invest in physical retail, direct mail, call centers, outdoor advertising, television, radio, and the like. (Just look at Amazon’s 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods.) A greater focus on digital doesn’t mean that the other channels go away—rather, it means that companies have more ground to cover than ever before.

Regardless of which channels it began operating in originally, a company’s organizational chart often reflects this type of channel or business expansion (see Figure 1.3). With each emerging channel, companies typically follow a pattern of leaning on outside experts and then building those capabilities and skills internally as it becomes clear that they are core to the business’ long-term success. New groups get built and slotted next to existing channel teams, each with its own strategies, visions, plans, and incentives for creating customer experiences. This redundancy leads to fragmented channel experiences, as well as more complexity in connecting touchpoints across functions and channels.

Channel proliferation (and its resulting effect on organizational structure) has made life complicated for even relatively small companies. How much should be invested in each channel? How can traditional channels be maintained while shifting into emerging channels? How do you manage all these channels? Who owns which channel and how do you get on their priority lists?

FIGURE 1.3

A representative organizational chart reflecting the separation of functions combined with channel proliferation.

When taking this all into consideration, remember this one fact: customers don’t really care about channels.

Channels Don’t Exist in Isolation

What do customers care about? They want products and services that deliver for their explicit goals and implicit needs. Customers care about how organizations treat them, how their time is spent, and when and where they interact with products and services. In this landscape, channels are a means to an end.

Historically, organizations have viewed customer interactions and the channels that support those interactions—phone, store, and web—through a one-to-one lens. Each channel’s team delivers solutions to support customer tasks with their channel. But this doesn’t reflect the reality of how customers move across channels and connect with products and services.

People interact with many channels every day. They also switch among them—sometimes by choice, sometimes not. A commuter hears an advertisement on a podcast for ordering glasses online, checks out the website, and orders a sample kit, receives the kit a few days later, tries to chat online with customer service, and then finally calls a toll-free number to get her questions answered (see Figure 1.4). This type of scenario plays out millions of times every day with all sorts of products and services.

FIGURE 1.4

Companies organize by channel, but customers move across channels in predictable and unpredictable ways.

Yet, customers don’t think about channels. They navigate the options available to them based on knowledge, preference, or context. Pathways can be designed to try to nudge customers to stay or move to a specific channel, but humans envision their own pathways where it is more attractive, useful, or expedient.

The general wisdom is that customers have these preferences, but organizations still spend a lot of time and energy to optimize channel investments and move customers to low-cost channels. Digital transformation efforts (common to most companies the last two decades) have moved jobs performed by employees to customers themselves (i.e., self-service).

Customers also do not care about what groups own the channels that support their experiences. An IKEA customer having an issue with the online store can easily walk into their local store to complain because, to the customer, it’s all IKEA. The physical store team likely had little to no role in the online experience, yet consistency and continuity of experience is the customer’s expectation.

Over the last 20 years, organizations have been told by analysts and consultants to strive to be omnichannel—available to customers in multiple, coordinated channels. Brand teams push to have a consistent look, voice, and tone in all their channels. Marketers attempt to create continuity in messaging while optimizing for high-impact channels. Technologists define architectures to share data and track customer actions across channels. As a result, much talk and effort goes into determining not only what channels to invest in, but also how to coordinate people, processes, and technologies to support and connect them.

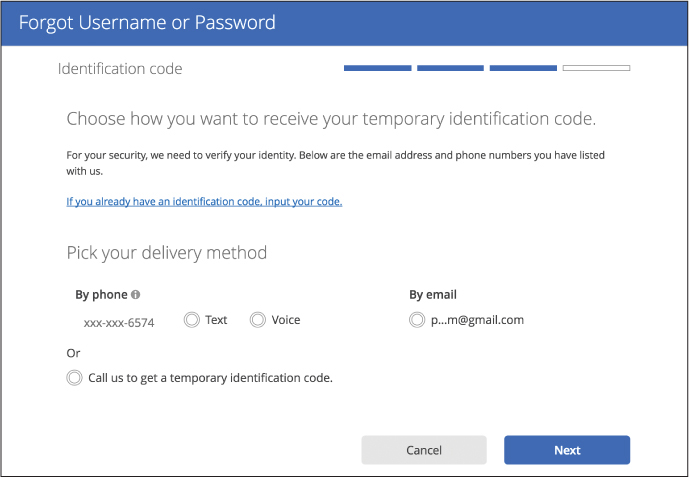

This gets even more interesting when you look at the opportunities to mix and combine channels. A simple example is reflected in secure authentication experiences. In Figure 1.5, a user forgot her password to an online bank account. A typical pattern would be to ask her to fill in some information, such as the last four digits of a Social Security number and a bank account number. If she gets that right, then she is presented with the option to receive a passcode by email, text, voice, or (in unfortunate situations) by mail. This security requires the user to interact with two channels: web and text, web and email, mobile app and text, mobile app and email, or web and mail. The end-user here is trying to get one thing done—recover a password—but multiple channels are leveraged for security while offering the option of which channels to support user preferences.

FIGURE 1.5

Most online banks offer customers the option to combine the web channel with text message, voice, email, or IVR to complete the password retrieval process.

As much as companies try to organize and optimize investments, people, and processes by channel, they don’t exist in isolation. Customers maneuver among them, and smartly combining them can lead to innovation and delight. Yet, to be able to orchestrate experiences across channels, you must understand each channel’s unique material.

Channels Reflect Interactions, Information, and Context

To design for good product and service experiences, you must know the capabilities and constraints of the different channels at your disposal. Designing a form delivered via a mobile channel is very different than designing one delivered in print. Creating advertisements for web, outdoor, and television requires different skills and expertise. This means that organizations need specialists for each form to be defined, designed, and executed. These specialists are typically organized by channel (i.e., digital) and then by a specialty in that channel (i.e., web, mobile, etc.). A hierarchical taxonomy of channels based on technology, however, gets muddy fast in the context of defining and executing end-to-end experiences.

As an exercise, list common channels in your business by media, and you will find overlap, redundancy, and conflict. Some of these channels are defined by their context of use (mobile), some by the means of interaction (tablet), others by their technological means of distribution (web), and still others by the content or information they distribute (social media).

A better approach is to define channels by three qualitative facets—interaction, information, and context.

• Interaction: What means does the customer use to interact with you? Examples include touch devices, mouse and keyboard, keypad, or voice (see Figure 1.6).

• Information: What is the nature of the content being provided to, or exchanged with, the customer? For example, social media.

• Context: What is the context—from environment to emotion—in which the interaction is happening. For example, physical stores.

FIGURE 1.6

The materiality of a channel creates opportunities and constraints.

A channel may be defined by one or more of these facets. Thinking explicitly about each channel through this lens ensures that you are not overlooking the unique material of a channel and how best to leverage it to support customer needs.

Channels Support the Moment

The concept of channels is just that—a concept. Channels help functions and support reaching a company’s objectives—from marketing to operations to products.

This is where the challenge rears its ugly head again. Channel specialists, working in isolation, lack an overarching view of what customers will experience in other channels. They see their channel as the primary (if not only) point of customer interaction, not as one of many possible enablers for meeting customers’ needs.

Put another way, defining channels as destinations obfuscates their supporting role of enabling and facilitating customer moments in different contexts. A customer shopping in a physical store while using her mobile phone to talk with her spouse and comparison price-check via an app does not represent three separate users in three different channels. She is a single person in a decision moment in which each channel can help or hinder her experience.

When a passenger books a ride with a ride-sharing service, she receives a confirmation message. This message can be delivered by text, push notification, within the application, or via a phone call from the driver. Each option, delivered via a channel, supports what really matters—the passenger knows the car is on its way (see Figure 1.7).

FIGURE 1.7

Multiple channels can deliver a confirmation message. Which channels are used by a customer depends upon their needs, context, and the capabilities of their mobile device.

Viewing channels as serving customer moments can empower you and your team to work backward from customer needs to which channel(s) will best facilitate meeting those needs. Instead of starting with one channel—digital—start with your customers’ needs, context, and journey. What role could print, mobile, web, environment, voice, or people play to support those needs? Can you combine channels in interesting ways? Can you build bridges between channels that help customers move forward easily?

And, most importantly, how do these channels support great customer moments?

Changing the Channel-Centric Mindset

Evaluating your channels in this way creates the opportunity to rethink the relationship of the individual channels and how they may work together. You can readdress how they are defined or what each channel’s role could be in a customer’s end-to-end experience. At a minimum, you will shift your vantage point from channels as destinations to channels as moment enablers. This conceptual foundation is an important first step in changing the channel-centric mindset.

As discussed, this mindset creates barriers—both conceptual and organizational—that make defining and designing good end-to-end experiences difficult. Changing how your institution organizes people around channels and functions (rather than customers and journeys) is a long game. However, as shown in Figure 1.8, you can begin engaging your colleagues immediately by turning your world 90 degrees and looking at it from a customer’s perspective.

FIGURE 1.8

The framework on the bottom positions channels as enablers of an end-to-end experience, not parallel worlds.

Customers do not contain their actions to one single channel. Stating this to your colleagues will not set off fireworks, but showing it will flip on light bulbs. The next chapter will go into greater depth about how to use a simple framework—a touchpoint inventory—to inventory and visualize how customers interact with your product or service over time. To get ready to create your inventory, you will need to define your channels first.

Codify Your Channels

Your organization likely has some recognizable customer channels, such as websites, mobile apps, call centers, physical stores, and so on. A specific product or service may leverage all or only some of these channels. You also may have a greater or lesser presence in different channels. Here are some approaches to get you started. In general, remember to keep in mind the three facets discussed previously: interaction, information, and context.

1. Start with the obvious. What are the major channels you support or where you interact with customers? For example, a customer setting up, placing, picking up, and refilling prescriptions at a CVS Pharmacy at Target may interact with multiple channels owned by the two companies (see Table 1.2).

TABLE 1.2 COMPARISON OF CHANNELS

Target |

CVS |

Target.com: Pharmacy |

CVS.com: Target |

Store—Main Line |

Pharmacy—Direct Line |

Physical Environment (Parking, Signage, Displays, etc). |

Physical Environment (Signage, Displays, etc). SMS/Messaging |

Target Mobile App |

CVS Mobile App Direct Mail |

2. Choose the right granularity. As you identify channels, go beyond broad categories such as “web” or “print.” A finer granularity will help you think more strategically about how to use specific channels and to identify where new channels are needed. If you have State Farm insurance, for example, the mobile channel has multiple native applications (see Figure 1.9). Differentiating each of these as separate channels helps clarify the current and future roles of each application in supporting different customer needs and contexts.

FIGURE 1.9

In larger, more fragmented product and service ecosystems, a more granular definition of your channels can help reframe what each subchannel really offers customers and how they relate to other subchannels.

3. Be specific. In some cases, you may be delivering different experiences based on the technological affordances of different devices. If your website has different features or touchpoints on larger screens than smaller screens that are assumed to be mobile, define those separately. For example, “Standard main website” and “Mobile main website.” This will help you parse and reimagine how to design for varying intersections of technological affordances and customer context.

4. Note who owns each channel. As you take stock of relevant channels, you should note which groups and accountable executives own them. In some cases—as in the CVS pharmacy at Target example—you also want to determine what external vendors or partners make decisions related to specific channels. As later chapters will reveal, you will need to reach out and actively collaborate with these people in the future.

5. Be ready to adapt. You will probably discover new channels as you and your team go beyond the obvious. Over time, you will also see your channel mix change—either through your efforts or others. Just get a good foundation, start your digging, and adjust as needed.

Build the Orchestra

A helpful analogy for understanding and explaining to others this shift from channels as destinations to enablers of end-to-end experiences is an orchestra (unsurprising, given the title of this book).

What About Research?

In an orchestra, you have many instruments playing in concert with one another. The conductor determines (working from sheet music) which kinds of instruments will help bring the piece to life. What does each instrument need to play? When do they play solo? Where do they harmonize with other instruments?

Orchestrating experiences means approaching channels with this thoughtfulness and intent. Within each broad category—web, mobile, email, environments, call center, and so on—determine what channels exist. What is each channel’s role? Where are your channels out of tune? Where are they creating dissonance? When you widen your lens beyond individual channels to customer moments enabled by channels, you will open new opportunities to orchestrate and reimagine the end-to-end experience.

We’ll now move on to the notes your instruments play—touchpoints.