CHAPTER 7

Identifying Opportunities

Opportunities Are Not Solutions

Opportunities, Intent, and Timing

CHAPTER 7 WORKSHOP: Opportunity Identification and Prioritization

When you look across the range of experiences that people have in their journeys, patterns will emerge. You will see commonalities in what people need and how they want to interact. You will also discover many gaps and inconsistencies in how your organization supports those needs, behaves in different channels, and provides clear pathways. In short, you will see missed opportunities to provide value and a lack of coherence in experience across time and space.

Understanding merely sets the stage for action. How do you and your colleagues determine where to focus and when? You begin with identifying opportunities rigorously and collaboratively.

Opportunities Are Not Solutions

Let’s get this out of the way: opportunities are not solutions. Humans are natural problem solvers, and this instinct makes it easy in corporate environments to jump quickly to how to do something while skipping over what you are trying to solve. Stop us if you have heard this one before:

You learn in your research that customers feel the onboarding experience takes too long. It’s one of many insights, but it sticks out as a problem ripe for addressing. Immediately your colleagues start discussing how to reduce the number of screens. The logic: fewer screens equal less time; less time equals happy customers. Discussions turn into whiteboard sketches and requirements, and before you know it, a solution is on the fast track to execution.

This scenario plays out over and over in product and service teams: one business metric or a perceived customer pain point leading to hasty decisions while obfuscating better opportunities to improve or innovate an experience. In our example, the opportunity is defined cursorily as “How might we reduce the number of screens?” This narrow frame ignores other insights into customer needs and closes off the possibility of exploring other solutions.

It may seem obvious, but the road to bad product and service experiences is littered with solutions delivered without first asking: “What’s the real opportunity here?”

What Is an Opportunity?

An opportunity is a set of circumstances ripe for creating positive change. Change can mean soothing customer pain points, extending your product or service to address unmet needs, or radically rethinking how those needs are met. Opportunities provide the fertile ground to create new value for an organization, its customers, and other stakeholders.

Identifying and prioritizing these opportunities should be done collaboratively and with rigor. The various sensemaking techniques from previous chapters can inform your understanding of organizational capabilities, customer needs, and the greater context that your product or service exists within. Based on these insights, opportunities can be framed properly to generate multiple ideas and potential solutions. This process ensures that you and your team frame the problem space accurately before imagining, much less making, possible solutions.

Orchestrating experiences means breaking away from business-as-usual, jump-to-a-solution approaches. It’s about embracing collaboration and creating true alignment to focus on the needs of customers and the most important opportunities that will serve the entire organization.

Take Airbnb as an example. The genesis for the popular home-sharing service wasn’t a reaction to business or technology trends but out of necessity. In 2007, founders Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia found themselves short on money to pay for their rising San Francisco rent.1 They knew hundreds of people were coming to the city for a conference in a city where hotel rooms were scarce and expensive. They recognized a real opportunity that they could potentially solve: supplementing their income by helping others stay for cheap. Chesky and Gebbia’s initial solution was a marketing website, three airbeds, and a home-cooked breakfast. Since then, Airbnb has evolved from a small experiment to a sophisticated set of services around the travel journey, but the company’s success initially occurred because it identified the opportunity of aligning host and guest needs.

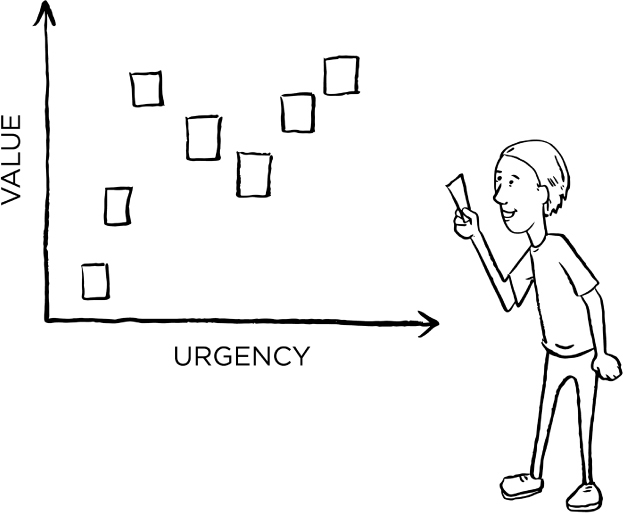

Every context has its own unique forces that could influence what separates true opportunities from red herrings. In the case of Airbnb, geography, economics, and the founders’ skills proved to be the right conditions to identify and solve for a real opportunity to create value. In general, there are three key requirements to check off when defining opportunities: value alignment, multiple possible futures, and the ability and resolve to change (see Figure 7.1).

FIGURE 7.1

The three facets of opportunities.

Value Alignment

Value creation is a cornerstone of many ideologies making their way into large organizations. Value stream mapping, for example, is a lean approach for identifying and eliminating activities that result in operational waste in the delivery of products and services. In the context of orchestrating experiences, designers similarly put an emphasis on ensuring that activities—which are instantiated as touchpoints—provide a clear value.

In business-centric organizations, the answers to these types of questions can be shallow or one-dimensional. Customers will be happy because the application will take less time. Call center employees will be happy to deal with fewer unhappy customers. And, of course, the company will be happier if the Net Promoter Score increases. It’s necessary to help your colleagues dig deeper.

It is important to clearly define and measure the business value of solutions, but a focus on experience means shifting the discussion from business value to co-value. Co-value means evaluating opportunities and solutions by how they will benefit all relevant stakeholders, not just the business. Overhauling an online application may increase conversions and decrease acquisition costs, but what value should be delivered to the applicant or to the employees who support acquiring and serving new customers? How would you define the opportunity differently from each stakeholder’s perspective, not just the interests of “the business” (see Figure 7.2)?

FIGURE 7.2

Look beyond business value to evaluate potential opportunities.

Applying a co-value lens to the process of identifying and prioritizing opportunities is a critical practice to shift to a human-centered mindset in an organization. Also important is an iterative approach—from research to opportunities and from solution definition through execution. The concepts and methods outlined in previous chapters will help you and your team change the conversation about value. Here’s a quick review:

• Touchpoints and touchpoint inventories: Evaluate current touchpoints or define new touchpoints by how they create value for the business, customers, and other stakeholders.

• Ecosystems and ecosystem mapping: Understand how different actors view, seek, and create value.

• Journeys and experience mapping: Identify gaps in the value that customers seek and what current solutions deliver at different stages and moments of the end-to-end experiences.

• Experience principles: Write guidelines for defining and making solutions attuned to customer needs and value while aligning with brand values.

Multiple Possible Futures

An opportunity should lend itself to many possible solutions. Let’s return to our onboarding example, but this time with a better framing and outcome:

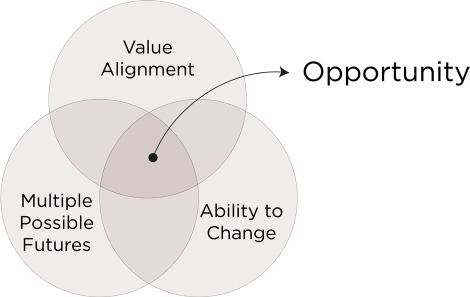

You learn in your research that customers feel the onboarding experience takes too long. This feeling applies to customers whose time to onboard varies from hours to days. Other insights from research reveal a lack of communication at key points that increase customer frustration, as well as a general confusion regarding the steps and information required to onboard. It’s clear there is a more systemic problem at play. As a result, you and your team frame the opportunity as “How might we help get customers up and running easily and confidently?”

As shown by this example, the framing of opportunities is critical to focus creativity and problem solving. The opportunity should be defined and worded to serve as a springboard to multiple possibilities, not an anchor to a specific solution (see Figure 7.3). Later sections of this chapter will walk you through how to frame opportunities properly with your colleagues.

FIGURE 7.3

Well-framed opportunities should inspire multiple possible solutions.

Ability and Resolve to Change

Even when there’s an opportunity to create co-value in multiple ways, you must always do a gut check of whether your organization can affect change and has the resolve to do so. This can be tricky.

When orchestrating experiences, challenging business as usual is part of the game. You will identify potential opportunities that often require people to partner in new ways across organizational silos. You will need your colleagues to be open to reframing success from opportunities that they alone can own within their respective silos to ones that call for collaboration and shared ownership. Building rapport and partnerships with key stakeholders will help create the conditions to be able to affect change when you see an opportunity.

Breaking down silos helps open new possibilities, but you and your colleagues will need to be clear-eyed and recognize that conditions will never be ideal. Thus, you will need to identify any true constraints within your problem space. If you can take action, there’s an opportunity. If you cannot take action—that is, if you cannot change something—it is a constraint. Seize your opportunities; embrace your constraints.2

In the context of orchestrating experiences, some examples of constraints might include:

• Your business strategy

• Regulatory rules that govern your activities and offerings

• Entities and events outside of your control, such as third-party services

• Risk tolerance

• Organizational structures, where stakeholders may be risk averse in co-owning outputs

You may have opportunities to work within or around constraints, but it helps to understand the difference when it comes time to create a plan of action for how to improve the end-to-end experience. For example, your insights may tell you that your customers don’t like giving their Social Security number during the application process because it makes them suspicious. However, for regulatory reasons, you cannot process the application without that information. You may then identify an opportunity to reframe or otherwise reposition the collection of this information. In this instance, you’ve done something important in identifying the constraint—and, instead of dismissing the insight as something you cannot change, you’ve created an opportunity.

Opportunities, Intent, and Timing

Value alignment, multiple possible futures, and the ability to change ultimately reflect the unique context of an organization and its ecosystem. When shifting an organization’s mindset from individual touchpoints to customer journeys, it’s critical to be clear on your overall intent and when you will take action.

There are three useful categories for defining and connecting opportunities to orchestrate end-to-end experiences better. They are the following:

• Optimize the end-to-end experience: Connect disparate moments into a connected system of channels and touchpoints.

• Reimagine the end-to-end experience: Extend the product or service experience to address unmet customer needs while emphasizing consistency and cohesion.

• Innovate from the ground up: Create new product and services designed as orchestrated end-to-end experiences.3

Optimize the End-to-End Experience

Any existing product or service experience typically has many opportunities for improvement. This should not be a surprise. Left to their own devices, different functional teams—marketing, product, design, technology, and operations—will have their own vision and priorities for optimizing within their area of responsibility. The interdependency of these silos means well-intentioned point solutions likely will cause issues elsewhere in the customer’s overall experience.

One common example: the lack of coordination between marketing and product or service teams. As a consumer, you have probably experienced a phenomenon that Brandon Schauer has labeled the service anticipation gap.4 Marketing’s traditional role is to create desire and anticipation for what a product or service will provide. Far too often, however, the delivered solution reflects a separation of vision, coordination, and execution among internal teams who support the same customer journey. For instance, imagine an airline that pours money into advertising a friendly flying experience but delivers poor experiences across checking in, boarding, and in-flight experience. How much revenue and customer happiness could be realized by connecting these dots, even incrementally?

Orchestrating experiences means changing this paradigm. It shines a light on numerous customer pain points hiding in plain sight once you frame customer engagement as an end-to-end experience to be designed collaboratively. The methods of this book—touchpoint inventories, experience mapping, and so on—support an important piece of work for modern organizations: optimizing the end-to-end experience.

Beyond Pain Points

Optimization in this context means systematically overhauling an existing product or service journey to be more consistent, cohesive, and complete. These changes often don’t mean major new investments, but rather smarter use of existing or planned investments by orchestrating activities across teams. A few common examples:

• Removing customer touchpoints that add no value

• Changing existing touchpoints to work better as a system

• Creating new touchpoints that support core customer needs better

• Extending touchpoints into more appropriate channels

• Building better bridges between channels and contexts

• Applying common experience principles to all parts of the end-to-end experience

• Creating stronger starts and ends to a customer journey

• Attacking a low point and amplifying a high point

• Cooperating across silos to have different channels work together to serve a touchpoint

• Creating a smoother transition between journey stages

Many of these opportunities represent low-hanging fruit—many bumps in a customer’s journey that can be corrected with small investments yet cumulatively produce a positive uplift in experience. Others may require more rigor to balance trade-offs across functional areas in support of the overall customer journey. And some opportunities may lead to new product or service touchpoints that meet existing customer needs more effectively.

For example, Rail Europe International found that customers greatly valued the current ability to build travel plans across different rail travel providers without having to go to multiple sites (see Figure 7.4). However, customers still found difficulty in creating itineraries because they could not visualize the physical locations of stations and other places they wanted to visit. Instead of jumping from booking site to booking site, they were juggling one booking site with maps, guidebooks, and other resources. This represented an immediate opportunity—they asked, “How might we help travelers visualize space and time more clearly when planning itineraries?” Overall, optimizing an end-to-end experience means shifting from improving touchpoints in isolation to designing the whole customer journey as a coordinated team.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

FIGURE 7.4

Optimization opportunities identified for Rail Europe.

Reimagine the Experience

Beyond optimization, there are opportunities for expanding or reimagining experiences to address a wider set of unmet customer needs. Here, the focus is not on which current customer touchpoints need to be improved or better connected, but on identifying opportunities to deliver new value. Opportunities that lead to reimagining parts or all of the end-to-end experience often result in new investments in people, processes, and technology. For this reason, an organization must do its homework to feel confident that acting upon these opportunities individually or in concert will likely create appropriate returns on investment for relevant stakeholders.

As noted in previous chapters, both ecosystem and experience mapping can reveal valuable insights into opportunities to solve for unmet needs. There are a few common patterns.

• Ignored or underserved journey stages. Many products and services are designed to support only use cases divorced from a greater context. For example, visiting a museum includes more than just experiencing the exhibits. The journey stages before and after offer great opportunities to provide new value and extend the museum experience.

• Not serving the greater journey. Instead of optimizing a current end-to-end experience, new opportunities may exist in a higher level of journey. Airbnb started with a focus on guests staying with hosts. Today, they focus on the overarching travel journey to provide more extensive value and differentiated experiences.

• Unaddressed actors. Ecosystem mapping often brings greater focus on other people that matter in a problem space. A common example is people—partners, family or friends, or third parties—who are part of the decision-making process. For example, in home buying, realtors may represent a new opportunity for engagement.

Reimagining goes well beyond the surface layer of an experience. The objective is to determine systematically how to redefine a portion or all of the why, what, and how of a product’s service. This includes:

• The strategic rationale and intent (why)

• The value that will be created for stakeholders (why)

• A vision for the end-to-end customer experience (what)

• The role of different people, touchpoints, channels, processes, and technologies (what)

• A plan for how to evolve to the vision over time (how)

• The design and implementation of touchpoints and operations (how)

Innovate from the Ground Up

One of the tougher areas to identify involves opportunities to create innovative experiences while innovating with new business models. By default, this is where start-ups usually take advantage of an approach of orchestrating experiences. They don’t have a mature offering to optimize or extend. Instead, they are hoping to innovate or disrupt an existing system.

A good example of new product and service innovation is UberEats (see Figure 7.5). Uber’s core service—transporting people from A to B—was built upon a sophisticated infrastructure that orchestrated the just-in-time movement of vehicles across geographies. Much of Uber’s value is this platform, and the company has been looking for new ways to leverage it. In 2015, Uber began experimenting with food delivery. While delivering food instead of people involves pick-up and arrival common in their core service, new challenges needed to be solved from orchestrating restaurant and food selection, to meal preparation, to partner management, and to drivers leaving their cars to complete the process.

FIGURE 7.5

The end-to-end UberEats experience was prototyped and piloted in three months.

To get a pilot in place quickly, an Uber team held a service design innovation workshop with colleagues to dig deeper into opportunities for providing a complete food delivery end-to-end experience.5 These workshops then led to ethnographic research to understand the food delivery ecosystem: customers, restaurant employees, and drivers. With better insights in hand, the team was able to concept, design, and launch a service pilot (bootstrapped to the existing Uber ride app) in three months. Several iterations later, UberEats has evolved to a full service operating in dozens of cities with a stand-alone app.

Unlike startups, more established companies spend a great deal of time and energy on optimizing what currently exists. While these incremental improvements keep the train running, we have observed innovation teams center their efforts on new technologies or external competitive threats, not the needs of people and their experiences over time and space. Getting a cross-functional team aligned around a better understanding of both the ecosystem and journeys of customers primes the pump for rethinking how things are done.

The HomePlus case study from Chapter 3, “Exploring Ecosystems,” is a good example of this. HomePlus did not simply try to improve the existing experience of going to the supermarket. They looked at their ecosystem with fresh eyes and found alignment with a common journey with which they could align—the daily commute. The resulting solution leveraged many of the operations needed for home grocery delivery wrapped in a unique shopping experience that required minimum behavioral change from customers.

In the end, organizations need to balance efforts and investments in experience across all three categories of opportunities. If you own or contribute to the end-to-end experience within a specific problem space, you should always ask these questions:

• What opportunities do we have to optimize the end-to-end experience to meet the needs of all stakeholders better?

• What opportunities are there to reimagine parts of the customer journey to create new value?

• What opportunities exist to disrupt how we and our customers could frame our relationships and the values we exchange?

AMAZON AND THE NEXT HORIZON

Amazon may be the paragon of identifying opportunities across all three categories. Amazon is known for optimizing every part of their experience. They also reimagine how their customers engage with that shopping experience, from introducing Amazon 1-Click, to extending the ecosystem beyond their digital channels, such as creating dash buttons for buying products as needed and in the context of when that need occurs (for example, buying detergent when your machine runs out). With AWS (Amazon Web Services), they identified the opportunity to take existing technical and data infrastructure investment and turn it into a whole new business—turning a cost center into a profit center. They rethought the actors in the journey, and they are constantly owning more parts of the shipping experience. Kindle, Prime, Echo, drone delivery, and so on—they are on a constant, obsessive mission to identify opportunities to optimize, reimagine, and reinvent.

Many approaches exist to identify and compare opportunities. The next section outlines a common design strategy approach for codifying opportunities as “How Might We?” questions. Techniques for prioritizing opportunities are also provided.

Identifying Opportunities

For identifying opportunities for end-to-end experiences, the overarching philosophies of the book apply to this step of the process:

• Look holistically across customer types, channels, touchpoints, and the context beyond your product or service.

• Perform qualitative research to make sense of your customers’ needs, personal ecosystems, and experiences.

• Leverage touchpoint inventories, ecosystem maps, and experience maps to synthesize and communicate your growing understanding of your customers’ broader journeys and discrete interactions with your product or service.

• Work collaboratively across functions throughout your sensemaking to create alignment and collective understanding.

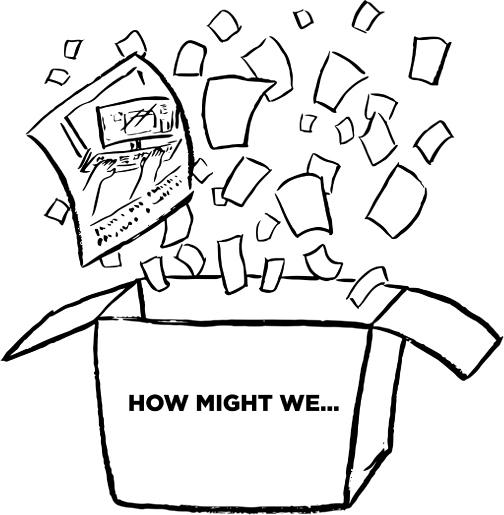

Labeling Opportunities

Invitation stems—commonly called, “How Might We?” prompts—are an effective technique for framing opportunities. Pioneered in the 1960s by Dr. Sydney J. Parnes,6 “How Might We?” prompts encourage lateral thinking and increase the quantity of possible ideas by posing questions. For example, if you have observed a pain point during customer onboarding, you could pose: “How might we make the onboarding process more efficient or steps clearer for customers?”

The key to crafting “How Might We?” prompts is to avoid going too broad or too narrow. Specifically, you should pull out any language that steers toward a narrower set of solutions. Table 7.1 shows some poor examples and how to reframe them.

As shown in these examples, you should avoid embedding solutions—such as specifying the channel, medium, touchpoint, or means (e.g., training)—in your prompts. They should inspire open brainstorming and idea generation well beyond the obvious.

TABLE 7.1 CREATING GOOD HOW MIGHT WE? STATEMENTS

Poor |

Better |

How might we create better aisle signage to help customers find products more easily? |

How might we help customers find products more easily while in the aisles? |

How might we use a mobile app to help customers keep doing product research when they leave the store? |

How might we help customers continue their product research when they leave the store? |

How might employees be trained to be more welcoming? |

How might we provide a better sense of welcome when entering? |

How might we educate customers in a graphical way on why it takes so long to do a return? |

How might we set and manage customer expectations better when returning merchandise? |

Prioritizing Opportunities

Numerous prioritization methods exist in design, business, product, and innovation literature. You can use simple methods—such as dot voting or the MoSCoW method7—to get a rough feel, but when possible, use an approach that uses at least two criteria to assess your opportunities. The criteria you use should be based on your strategic focus—optimization, reimagining, or innovation—and be clear to all participants. Here are two prioritization methods to consider for different contexts (optimization, imagination, or innovation). A third prioritization method—impact vs. complexity—that can also be used to prioritize opportunities is covered at the end of Chapter 8, “Generating and Evaluating Ideas.”

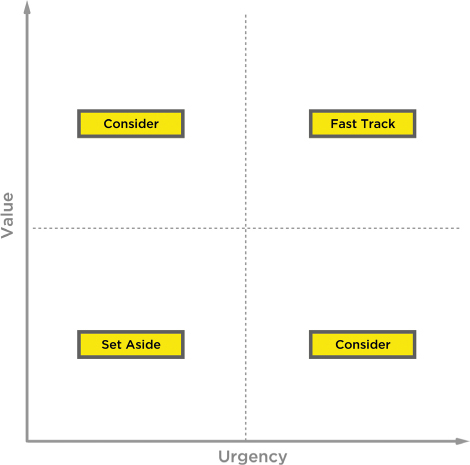

Value vs. Urgency (Optimization or Reimagination)

Optimization efforts typically focus on immediate to near-term actions that you can take to address specific metrics related to your product’s or service’s end-to-end experience. Your objective in this exercise is to assess each opportunity against the co-value it could produce and how urgent it is to solve for sooner rather than later.

Optimization efforts typically focus on immediate to near-term actions that you can take to address specific metrics related to your product’s or service’s end-to-end experience. This technique assesses each opportunity against the co-value it could produce and how urgent it is to solve for sooner rather than later. Figure 7.6 illustrates a simple model you can use to visualize and plot your analysis. The workshop following this chapter provides an example of how to use this method with your colleagues.

FIGURE 7.6

Prioritizing against value and urgency.

Satisfaction vs. Importance (Reimagining and Innovation)

This approach works best when part or all of your focus is smoothing out the rough edges of the end-to-end experience. In this case, timing or effort is less important than identifying opportunities to provide value outside of your current product or service paradigm. Uber’s extension into food delivery and Airbnb’s push into the broader travel experience are two good examples of this situation.

In this exercise, you will use a modified version of Opportunity Scoring from Anthony Ulwick’s Outcome-Driven Innovation methodology.8 Using a scale of 1 to 10 for both satisfaction and importance, discuss and rate each opportunity from the perspective of your customers. How ripe is the opportunity for a new solution? Did you learn in your research that other products and solutions already meet customers’ needs? As you discuss, plot your items visually against the model illustrated in Figure 7.7.

FIGURE 7.7

Opportunity scoring assesses opportunities against importance and satisfaction.9

For this method to work, you will need to have your insights from research handy to represent your customers’ needs and perceptions of how well existing products and services meet those needs. This means it’s critical to design your research to surface undermet and unmet needs within your customer base (or in new customer segments that you want to serve). Of the frameworks covered in Chapters 1–4, ecosystem maps are especially useful for this type of opportunity identification and prioritization. Ecosystem maps include products, services, and other people and things that customers may already turn to. For example, potential UberEats customers may already use food delivery services, so research into that space may reveal opportunities in portions of the journey that are more underserved than others.

Communicating Opportunities

At some point, you and your colleagues will be ready to share more broadly the opportunities that you have discovered and prioritized. Here are a few approaches that you can use to get buy-in on priorities and to prepare your organization to jump smartly and confidently into solution mode.

• Opportunity cards: Making each opportunity, or recommendation, into discreet items helps break down some of the high-level critical details for the opportunity, such as channel or LOB ownership and key dependencies (see Figure 7.8). Just as important, it allows you to tie it specifically to the things that lead to the opportunity: the business value or customer need that was identified. This can provide traceability for people who become aware of the opportunity who weren’t a part of the past work. Other stakeholders can see the justification for prioritizing this opportunity.

COURTESY OF ADAPTIVE PATH

FIGURE 7.8

Opportunity cards are often half sheet (A5) or quarter sheet (A6) that provide some detail on dependencies or traceability for how you arrived at this opportunity.

• Opportunities by stage: Organize your opportunities by stage of customer journey or across two or more stages. (See Figure 7.12 in the workshop at the end of this chapter.)

• Experience map annotation: An alternate approach to show opportunities by stage involves taking your experience map and annotating it with your opportunities. You can call out the opportunities in a separate section of your map. Or you can create a version of your map fading back to the current state and overlaying your opportunities.

• Opportunities by channel and stage: You may have many opportunities that, regardless of how they are solved, apply to specific channels. In this situation, using a framework like a touchpoint inventory—channels as rows and journey stages as columns—will highlight the recommended focus in different channels across the end-to-end experience.

• Opportunity map: An opportunity map categorizes opportunities by theme and often includes other insights or information, such as experience principles (see Figure 7.9). This type of artifact provides stakeholders with an at-a-glance view of where design intervention can create better experiences and new value. The opportunity map can then support determining which opportunities to pursue, when to go after them, and which aspects of the customer journey would be impacted.

FIGURE 7.9

An opportunity map Chris and his team created at Adaptive Path for an energy sector client.

• Ecosystem opportunities: Similarly, an ecosystem map can be annotated with opportunities to show how new or reimagined products, services, other entities, or relationships can create new value.

One approach to visualizing your opportunities usually does not communicate the full story that you need to tell. Look to combine vantage points, such as by journey and by ecosystems, to help people see what you and your colleagues see—the best opportunities to create more value and better end-to-end customer experiences.

CHAPTER 7 WORKSHOP OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION AND PRIORITIZATION