CHAPTER 4

Orienting Around Journeys

There Are Many Types of Journeys

Journeys Are Valuable to Everyone

Journey: The Hub of Empathy and Understanding

Unpacking End-to-End Experiences

Up to this point, we have unfolded a conceptual canvas of channels, touchpoints, people, places, things, and relationships upon which an infinite number of customer stories and interactions can play out. Now, let’s explore one last framework integral to understanding experiences that occur over time and space—the customer journey.

With many proponents across customer experience, user experience, service design, marketing, and other tribes, the customer journey has become a ubiquitous term in academia and industry. The core concept is simple: a customer journey represents the current state of an end-to-end customer experience. Customer journeys, in general, help an organization better understand the pathways that customers follow when buying a product or using a service. As we will cover in more detail, customer journeys come in many shapes and sizes, from long and broad (e.g., buying a home) to short and compact (e.g., checking in for a flight).

Many methodologies exist for defining customer journeys and using journey frameworks to set strategy, inform design decisions, and measure the performance of touchpoints. The growing popularity of modeling customer journeys has also led to some backlash challenging whether they deliver upon their intended value. In many ways, customer journey maps have followed a similar pattern as personas: they are widely used but often misunderstood, created in silos without rigor, and shelved without being used properly in the design process.

Customer journeys can be an invaluable concept when framed appropriately and tied to a methodology that connects strategy to planning and execution. Later chapters will arm you with the mindset and methods to do just that. But first, what is a journey?

What Is a Journey?

In the context of orchestrating experiences, think of a journey as the conceptual trip a person embarks upon to achieve a goal or satisfy one or more needs. This may be a customer shopping for a product, a patient seeking treatment for an illness, an employee going through his first 90 days at work, or a citizen participating in an election. In all these cases, a person navigates the world around them, interacting with various people, places, and things across time and space. These journeys likely have highs and lows, differ from what was expected, and lead to other journeys, planned or unplanned. This book focuses on the journeys of customers, but the concepts and approaches outlined are applicable to other types of people and contexts.

JOURNEYS ARE CONSTRUCTS

Journeys are constructs, not mental models. I once had a client who was concerned about calling a specific experience a journey because a marketing research team had shown in their findings that customers did not “think of their experience as a journey.” It’s important to remember that journeys are a construct to aid in the design of better experiences, not a customer mental model. A customer may not think of their experience as beginning before or ending after a major interaction with your product or service (that’s a finding!), but a journey framework can help put that key moment in a more useful context.

Journeys Are Made of Moments

A journey unfolds one moment at a time. These moments occur in many contexts and with different intensities of emotion. Booking a ticket online. Checking in at the airport. Having lunch in the premium lounge. Boarding the plane. Using the entertainment system. Collecting bags. Checking loyalty points. And on and on.

Each moment constitutes an opportunity for an organization to clarify its relevance and provide value through information and interactions. Information can be communicated in different ways—via a person, a recorded message, in print, static text on-screen, in video. Interactions can be simple or complex, one-sided or responsive, and with people or things. The basic equation, however, is simple: interactions with a product or service invoke both emotions and thoughts. These can be positive, negative, mixed, or neutral. These interactions can create a lasting memory or disappear into the ether.

An interaction does not happen in isolation. One moment can impact the next moment and others that follow. An eye-catching ad may inspire someone to try a new service. However, if signing up for the service is overly complicated or calling customer service creates more confusion than clarity, the value promised in the advertisement becomes a broken promise.

New experiences can color our memories of previous interactions with a company and its offerings. A handwritten apology for poor service can lessen the intensity of one’s recollection of the events that generated the apology. An automated “how was our service” call that wakes you up in the early morning can obfuscate positive memories of your service experience.1

In the end, the accumulation of these moments, the value they deliver, and the memories they create constitute a customer’s journey.

There Are Many Types of Journeys

Customer journeys come in many shapes and sizes. Journeys that teams have mapped and designed for include the following:

• Taking a day trip to a museum

• Obtaining and using a customer loyalty card

• Applying for a credit card

• Shopping for insurance

• Becoming a first-time investor

• Traveling by train in Europe

• Taking on a large home improvement project

• Buying a home

• Hiring and firing in the employee lifecycle

• Discovering and dealing with mental illness

• Surviving cancer

As you can see from this sample, a customer journey is a flexible concept. A journey can frame a relatively short and simple experience (e.g., a day at the museum), a long and complex one (e.g., buying a home), or the entire arch of a relationship over potentially many years (e.g., the employee lifecycle). You can use a journey model to define the pathways you want to create for customers, such as onboarding, switching services, or canceling a service. Or you can study relevant customer journeys to your service. For example, mapping the journeys of parenthood to identify unmet needs and pain points.

Figure 4.1 illustrates one example. Imagine that you were hired to recommend opportunities for providing more value in the customer experience for a major airline. Where does the journey begin? Where does it end? Is it even one journey? It depends on what you want to explore. Consider the following information:

• The travel experience: how does air travel fit within the overall journey of taking a trip?

• The overall airline service: from the trigger when the customer begins shopping for air travel through receiving a loyalty miles credit two days after returning home.

• The core air travel experience: from arriving at the airport through leaving the airport at your destination.

• A smaller service journey: getting a refund for a cancelled flight, using your loyalty miles to book a trip, or what happens when your bag goes missing.

FIGURE 4.1

Journeys within journeys.

Each of these journeys involves an experience that unfolds over time and across multiple touchpoints and channels. The broadest journey (e.g., the travel experience) approaches air travel as one service with a larger experience; the journey of using loyalty miles to book a trip is a service within the overarching service an airline provides. Conceptually, each of these levels provides insight into different (but likely related) customer needs and pain points, experiential context, and service opportunities. Where you focus is a strategic decision based on what you need to learn and what journeys you can directly impact.

Journeys Are Valuable to Everyone

Many disciplines have gravitated toward the concept of customer journeys to define strategies, design for experience over time, and modernize operations. Why? A convergence of several new best practices is underway, including:

• Staging experiences, not selling products and services

• Using data to build and manage customer relationships

• Measuring each touch

• Adapting to the mobile customer

• Meeting expectations for experience continuity

• Embracing emotions

Staging Experiences, Not Selling Products and Services

While many organizations preach “putting customers first,” the C-suite has dramatically increased its focus and investments in moving employees from thinking inside-out to outside-in. This evolution has been largely driven by consultancies of all stripes—management consulting, service design, marketing, and even technology—influencing their executive customers to shift their mindset from feature-laden products and services to creating differentiating experiences. Whether it’s the Voice of the Customer (VoC), design thinking, user experience, or customer-centric marketing, organizations are swimming in competing philosophies and frameworks for attracting and retaining customers over time. Against this backdrop, customer journeys have emerged as a valuable framework to understand how to stage experiences better.

Using Data to Build and Manage Customer Relationships

Marketing, once viewed with advertising as an art form of persuasion, has increasingly embraced more sophisticated data and modeling approaches to underpin where, how, when, and why a brand interacts with current and prospective customers. Conceptually, relationship management depends upon understanding who the customer is, measuring the quantity and quality of interactions with that customer, and determining what the next offer or interaction should be. Most medium-to-large organizations employ a customer relationship management (CRM) platform to manage customer models and track interactions with customers in every channel. Journey frameworks fit nicely with the intent of relationship management: it’s not about one touch—rather, it’s about how many touches build a relationship with a customer over time.

Measuring Each Touch

As interactions with products and services become increasingly digitized, organizations have greater insight into how each touchpoint impacts the customer experience. Did the customer open the marketing email? Did she read the product description? Was the product abandoned in her shopping cart? What search term did she use to find a better product? The collection and analysis of this data help reveal the pathways that customers take, stay with, and abandon. Journey models are useful for analyzing these pathways and identifying patterns to meet customer needs at and across touchpoints more predictably.

Adapting to the Mobile Customer

More widespread mobile computing has challenged organizations to rethink how they interact with digital customers. Overly simplified customer pathways, such as starting online and then coming into a store, neither reflect the fluidity of customer actions nor the reality of digital and physical channels merging in real time. Customer journeys capture the range of customer actions and help organizations identify where to optimize paths and design for channel pairing, not conflict.

Meeting Expectations for Experience Continuity

In a world of digital data and tracking, customers expect organizations to provide more continuity across channels and touchpoints. Have a problem with the flight you booked online? You expect the call center agent to have that information at his fingertips. Searched for a vinyl record on a mobile app? You want to pick up your search on your laptop. Framing customer experiences as journeys can help identify how customers move or want to move across and within channels, as well as where inconsistencies in utility, interactions, or language lead to confusion or frustration.

Embracing Emotions

The growing science around how emotions impact decision-making and brand perception have found their way to organizational leaders through books such as How We Decide, Nudge, and The Art of Choosing. The popularity of these concepts has aided marketers, designers, and others to lean confidently into new techniques for better understanding of customer emotions. Customer journey mapping meets this need, helping researchers identify and report upon the variety and intensity of customer emotions in product and service experiences.

Journey: The Hub of Empathy and Understanding

Hopefully, you see the value that customer journeys can bring to organizations grappling with the complexity of orchestrating experiences across many touchpoints and channels. Before we go further, we do want to be explicit: articulating your customers’ experiences as journeys does not replace other research approaches and models. It’s not always appropriate to gear your research toward understanding an end-to-end journey. You still need other frameworks and models, such as personas, to communicate critical insights into the needs, behaviors, and goals of customers. As with all concepts, customer journeys have their place; like all tools, experience mapping should not become the proverbial hammer searching for a nail.

To orchestrate experiences, however, a customer journey model effectively provides insights and context to stakeholders responsible for a range of decisions related to the strategy, design, and implementation of products and services. Other traditional user experience tools for connecting different parts of the experience, such as concept models, lack the elements of time and context. Scenarios communicate experiences over time, but their strength lies in individual customer stories, not a view of the broader range of actions, emotions, and needs among many customers. User stories tactically break down touchpoints into functionality, but they focus on minute tasks, not larger outcomes.

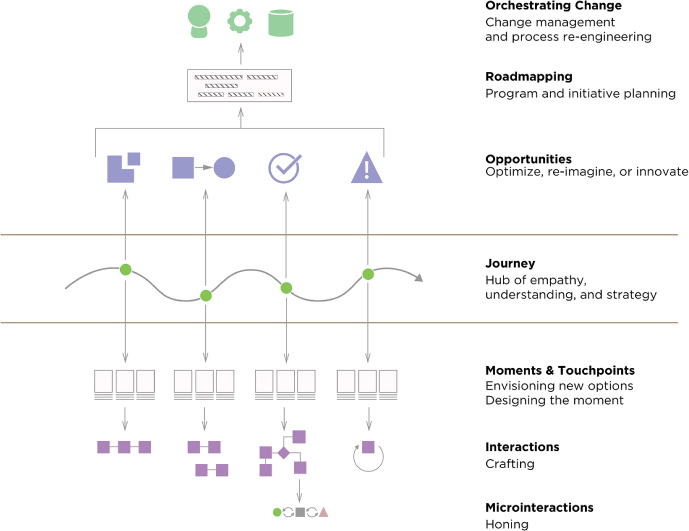

A customer journey provides insights into customer needs while also clarifying how different touchpoints and channels work or don’t work well as a system. For this reason, we call the customer journey the hub of empathy and understanding. Why a hub? As illustrated in Figure 4.2, the customer journey sits at the center of a continuum from the smallest customer interactions to the most critical organizational strategies and frameworks. Let’s explore the model in both directions.

FIGURE 4.2

The customer journey provides a hub of empathy, connecting the needs of customers from microinteractions to organizational strategy.

From Journey to Microinteraction

Any meaningful moment a customer has with a product or service exists within a greater context. The customer journey is a bird’s-eye view of the moments that matter and how they relate to existing or missing touchpoints. Customer journeys are invaluable for understanding where specific product or service touchpoints can better meet a need in the moment while bridging one moment to the next.

For example, most airlines include the ability for travelers to obtain a digital boarding pass. This pass is needed to check luggage, go through security, and eventually to board the plane. The question for airlines to answer in their end-to-end experience is: How do touchpoints that support “getting a boarding pass” bridge the traveler to the later moments in which “showing the boarding pass” is required? Your check-in experience can be smooth and delightful, but if the traveler struggles to produce their boarding pass later in the journey, the “getting a boarding pass” moment likely has room for improvement.

If you are responsible for experience strategy, viewing the experience as a journey can help identify the greater flow that a product or service should create. As a hub, the customer journey informs the design of each touchpoint to shine in concert with other touchpoints to make great moments. This also provides scaffolding—what we call the DNA of the journey—to guide more detailed interaction and microinteraction design decisions that are critical to create continuity and consistency across the end-to-end experience.

From Journey to Enterprise Strategy

In addition to guiding more detailed design and implementation decisions, a customer journey should be used as a strategic tool to inform strategic planning. As a hub, the customer journey can help a product or service team do the following:

• Identify pain points and opportunities. By providing an appropriate customer-centered context, opportunities for improving or creating touchpoints become clearer. These insights help drive what to do next and how to prioritize what will align business and customer value across the end-to-end experience.

• Make a plan. Customer journeys provide a good framework for roadmaps or evolution maps to communicate and organize efforts over time. These plans can clarify how typically disparate projects connect and result in an improved end-to-end customer experience.

• Organize across silos. The customer journey also clarifies what touchpoints are critical to the end-to-end experience and, as a result, what parts of the organization should be collaborating more closely. When a customer journey is embraced as the hub, aligning people and making trade-offs across silos become easier.

Moving further up in strategic importance, a customer journey is typically one of many your organization must create or support to reach its strategic objectives. Smart organizations holistically codify existing and emerging journeys that matter to their customers and business. They look across these journeys to identify patterns of needs to drive enterprise strategy for evolving their offers. They streamline and organize operational capabilities to support the prioritized journeys and moments.

Unpacking End-to-End Experiences

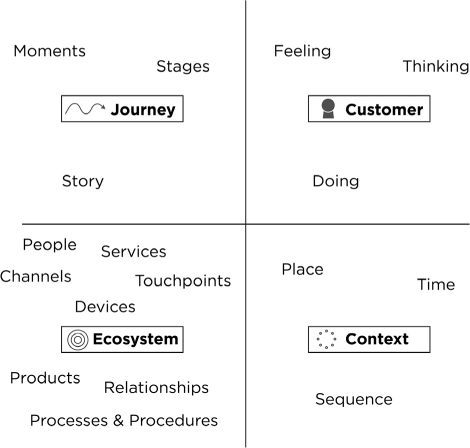

Understanding the end-to-end experiences of multiple customers with often dozens of touchpoints over time may seem like a fool’s errand. Fortunately, you can gain valuable insights into the customer journey by focusing on manageable sets of what we call building blocks of end-to-end experiences. As Figure 4.3 illustrates, these building blocks fall into four distinct categories: the journey, the customer, the ecosystem, and the context.

FIGURE 4.3

The building blocks of experience mapping.

The Journey

An experience map synthesizes the experiences of multiple customers. Approach each customer’s individual journey as a story with the following elements:

• The overarching story: What is the journey’s raison d’être? Why do customers embark upon the journey, what value is created, and what are their lasting impressions at the end?

• Moments: What events take place in the journey? Which moments do your products and services produce or play a role in? Which moments are more important to your customer? Or to your product or service?

• Stages: Do these moments occur in clusters that reveal a useful narrative structure? For example, the stages of an airline journey might be researching options, booking a flight, making other preparations, checking in, and so on.

When researching people’s end-to-end experiences, you need to stay open to letting the answers to these questions emerge from your data. What you find may differ from your organization’s current frameworks (e.g., conversion funnels or business-centric journeys) or your hypothesis greatly.

The Customer

Since customers are the protagonists of their own journeys, a key objective is to nail down how their behaviors, perceptions, and emotions change moment by moment and interaction by interaction over time. You also want to identify other underlying factors of their journey. The following three customer building blocks are important to understand: feeling (emotions), thinking (perceptions), and doing (behaviors).

Feeling (Emotions)

To design better products and services, you need to get closer to the messiness of customers’ lives and the feelings they bring to their interactions across your entire product or service (see Figure 4.4).

FIGURE 4.4

Emotions in specific moments should be placed within the context of the entire emotional journey.

You may be told that you have these insights already thanks to Voice of the Customer reports and Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys.2 These qualitative approaches are not designed to understand the context and nuances of interaction. Therefore, you must conduct qualitative research that answer questions such as:

• What emotions do customers experience throughout the journey?

• What moments or interactions dramatically impact how customers feel?

• How do emotions affect decision-making?

• To what extent do emotions reveal deeper motivations behind people’s actions?

• How well does the product or service identify, accept, and adapt to a customer’s emotional state?

Thinking (Perceptions)

Thinking concerns a customer’s mental model and how it is met or challenged and changes over time. For example, if you have purchased a home in the past, you have specific assumptions, expectations, and preferences that you take to your next home-buying journey. Each interaction with a product or service intended to help you find, finance, and move into your new home either matches or differs from that previous mental model.

The questions related to thinking that you need to answer include the following:

• What do different customers expect will happen at each key moment of their journey?

• When a part of the experience fails to meet the customer’s expectations, how does this impact their actions, emotions, and needs?

• What other products, people, or information help shape a customer’s mental model?

• How well does the product or service experience anticipate, address, or acknowledge existing mental models?

Doing (Behaviors)

Doing is about actions and behaviors. Some of these actions involve interactions with your product or service touchpoints; others reveal the broader ecosystem of people, things, and places (see Chapter 3, “Exploring Ecosystems”). Learning what customers actually do is typically an eye-opening moment for stakeholders who are used to looking at a limited set of data related to customer interactions.

Valuable insights related to behaviors include the following:

• What range of customer behaviors exists in the end-to-end experience?

• What do customers do to address specific needs during their journeys?

• How do customers’ actions deviate from their preferred or your organization’s desired behaviors?

• How do touchpoints, people, or places impact customers’ behavior?

The Ecosystem

A customer’s personal ecosystem greatly shapes their experience when intersecting with an organization’s product or service ecosystem (see Chapter 3). Think of a customer’s end-to-end experience as a distinct pathway through these colliding ecosystems (see Figure 4.5).

FIGURE 4.5

Different customers, different pathways.

Ecosystem entities that often appear in customers’ journeys include:

• Channels: What channels do your customers gravitate toward in certain moments or to meet specific needs? How well can they switch channels?

• Touchpoints: Which touchpoints do customers interact with and to what degree? What is the quality of those interactions? What touchpoints are missing from specific channels or missing completely?

• People: What role do agents of the product or service play in the customer journey? Are there other people—friends, family, and so on—who impact experiences, decisions, and behaviors?

• Other products and services: What other products and services make up the customer journey? Where do people turn to for information? What competitors are being considered, chosen, or rejected?

• Devices: What types of devices—laptops, kiosks, mobile phones, and so on—do people interact with and why?

• Relationships: How do different parts of the ecosystem relate to one another? Can you identify cause-and-effect relationships below surface behaviors and emotions?

• Processes and procedures: How do regulations, processes, and procedures dictate pathways, behaviors, and barriers for customers, as well as the employees who serve them?

The Context

Experiences do not happen in a vacuum. Experience mapping involves understanding and embracing how context impacts behavior, emotions, and mental models. When you are attempting to understand and codify context, consider elements such as:

• Place: Where are customers during their journeys? How do geographic locations impact their experiences?

• Time: What is the range of durations for different customers’ journeys? How long do they spend in each stage or moment? How do your customers think and feel about how they spend their time?

• Sequence: What patterns exist in customer behaviors from one moment to the next across the journey? How does one moment impact the next or future moments later in the journey?

Getting Started with Journeys

A journey paradigm can create strategic clarity, improved cross-functional collaboration, and more successful products or services. When journey frameworks are embraced to drive strategy, transformational change can result in new customer value propositions and the reorganization of people and processes to better support the end-to-end experiences of customers.

Big organizational changes start with small efforts that demonstrate better ways of learning, making decisions, and having an impact together. To gain support for making customers and their journeys the centerpiece of your product or service strategy, start with one journey. Step away from intent statements, product backlogs, sprints, and NPS scorecards. Step into the lives and stories of your customers to understand their experiences.