6. Sandvik Coromant Recycling Concept

This case was prepared by Associate Professor Gal Raz and Batten Institute Fellow Michel Schlosser. It was written as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright © 2010 by the University of Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rights reserved.

To order copies, send an e-mail to [email protected]. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of the Darden School Foundation.

It was August 2009, and Lars Hallberg was in his office in Sandviken, Sweden, preparing for a meeting the following week with the executive management of Sandvik Tooling. The purpose of the meeting was to review the Coromant Recycling Concept (CRC), a global recycling program for Coromant, the leading brand of Sandvik Tooling, a world leader in metal cutting tools with sales of (U.S. dollars) USD3.8 billion in 2008. Sandvik Tooling was one of the three business areas of Sandvik Group, the global high-technology engineering firm.

The CRC had been launched in 1996, but it was only recently that it had really gained momentum within the firm and quite a few challenges remained. Hallberg wanted the comprehensive plan he was preparing for the CRC to demonstrate its value for Sandvik.

Industry Overview

The world market for metal cutting tools was estimated to be (Swedish krona) SEK140 billion (USD20.5 billion) with 3% to 4% annual growth.1 Of this market, more than 75% comprised cemented carbide inserts and tools. Inserts were the small blade tips secured by a clamp to a steel tool2 (Figure 6-1) that provided the tool with its cutting characteristics.3 Each insert weighed only a few grams and cost approximately USD10.

1 From “The Sandvik World 08/09” (brochure), available at http://www.sandvik.com/sandvikworld.

2 Some tools were made entirely of cemented carbide and were thus called solid carbide tools.

3 Some cutting tools were equipped with up to 300 inserts.

Figure 6.1 Cemented carbide insert and related tools.

Sandvik Tooling helped pioneer the manufacture of cemented carbide for metal cutting, which could be traced to the early 1920s, when Osram developed the first cemented carbide cutting tool as a replacement for diamond-tipped tools.4 Cemented carbide offered a unique combination of hardness and toughness: harder materials existed, such as diamond, cubic boron nitride, and ceramics, but cemented carbide, a composite of tungsten and cobalt,5 was tougher (i.e., more resistant to sudden fracture). Cemented carbide was extremely durable and could withstand deformation, impact, heavy load, high pressure, corrosion, and high temperature. Finally, cemented carbide was a high-tech material6 that could be tailored to fit extremely precise application requirements.7

4 Other pioneers were Kennametal, which patented a tungsten titanium carbide composition in 1938, and Carboloy, which was the first company to introduce cemented carbide inserts for commercial use, in 1920. In 2009, Carboloy was part of Seco Tools, a metal cutting tool company owned by Sandvik but operated autonomously.

5 Cemented carbides were often made of some 10 to 15 different components, including titanium, tantalum, niobium, and nickel, but were typically 75% to 85% tungsten and 5% to 10% cobalt.

6 Material typically represented 7% of the total cost of an insert.

7 The process used for producing cemented carbide—powder metallurgy—allowed the inserts to be tailored very precisely through composition of the powder, shape of the press, parameters of the high temperature furnace, grinding, and coating. Coromant offered some 25,000 different standard products. Powder metallurgy was a resource- and energy-effective technology.

Cemented carbide first revolutionized mining tools, then gradually gained a dominant share of the industrial cutting tools market, particularly after the introduction of indexable inserts in the 1950s and coating in the 1970s. Sandvik Tooling launched the Coromant brand in 1942. After the consolidation that took place in the early 2000s, there were three major players in the world—Sandvik; Kennametal, a U.S.-based company; and Iscar, based in Israel—and several specialized niche companies. Sandvik Tooling controlled more than 25% of the market.

Tungsten and Cobalt

In nature, tungsten was found as an ore, mostly as scheelite or wolframite.8 The ores were concentrated and then processed chemically to produce ammonium paratungstate (APT), which, when heated in a hydrogen furnace, released very pure tungsten powder. In 2008, the world production of tungsten was 62,200 tons.9 Tungsten was used primarily in the production of cemented carbide (58% of world consumption)10 and steel (17%) but also in lighting, weapons, and chemicals. In 2008, China was the largest consumer (33%) and the largest producer (79%). World reserves were estimated at more than 6 million tons, with two-thirds of it in China.

8 Scheelite, also called white ore was calcium tungstate (CaW04); wolframite or black ore was iron tungstate (FEWO4) or manganese tungstate (MnWO4).

9 China: 50,000 tons, Russia: 3,000 tons, Canada: 2,277 tons, Bolivia: 1,148 tons and Austria: 1,122 tons.

10 In 2008, roughly 50,000 tons of cemented carbide were produced in the world. 22% of the volume (and 65% of the value) of cemented carbide were used for cutting tools (and for inserts in particular) applications.

Approximately half of the world’s cobalt was produced as a byproduct of nickel from sulfide and laterite deposits; an additional third was produced as a byproduct of copper operations, mainly in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia; the remaining cobalt mining came from primary producers. The world production of cobalt in 2008 was 71,800 tons.11 Cobalt was used in chemicals such as pigments and dyes (26% of total use); in batteries for cell phones, computers, and hybrid vehicles (25%); in superalloys for jet engine turbine blades (22%); in wear-resistant alloys including cemented carbide (12%); and as catalysts and magnets.

11 Congo: 32,000 tons, Canada: 8,300 tons, Zambia: 7,800 tons, and the United States: 6,300 tons.

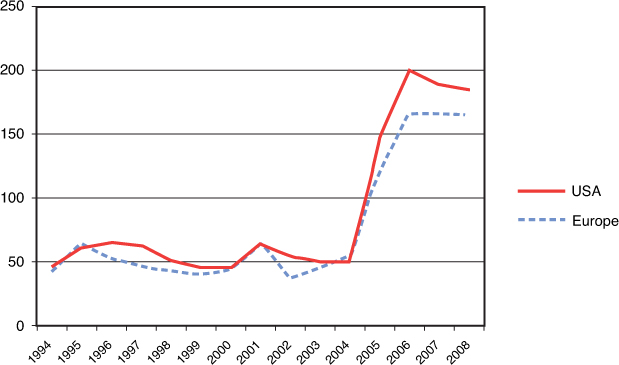

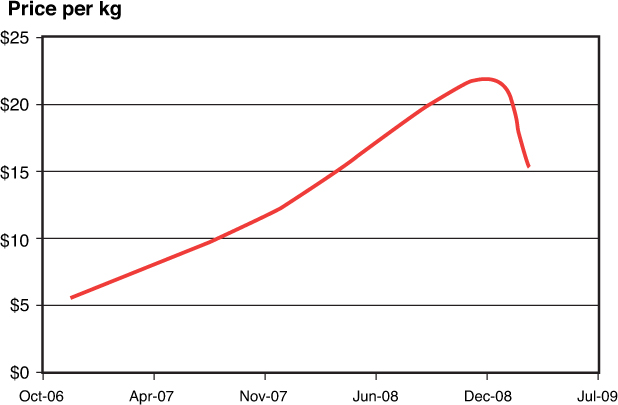

Prices for tungsten were quite stable from the mid-1990s to 2004; from 2004 to 2008, prices increased fourfold. During the same period, cobalt prices varied substantially, going from $30 in 1995 to $7 in 2002, then to $40 in 2008 (Exhibit 1).

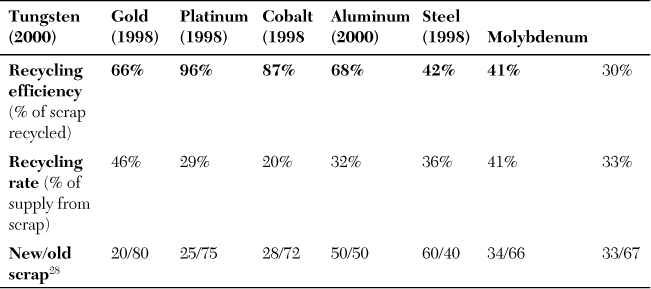

In the United States, tungsten and cobalt had end-of-life recycling efficiencies (the percentage of postconsumer metal recycled) of 66% and 68%, respectively, and it was estimated that 46% of the total supply of tungsten and 36% of cobalt came from scrap. Worldwide, 27% of postconsumer tungsten was recycled and 34% of tungsten was produced from scrap (Exhibit 2). Tungsten and most of its compounds had traditionally been considered substances of limited environmental liability but now came under more scrutiny.12 In 2008, toxicological information on tungsten and its compounds was limited.13

12 A study reported that metallic tungsten in soil had some adverse environmental effects at above the threshold level of 1% mass basis. See Nikolay Strigul et al., “Effects of Tungsten on Environmental Systems,” Chemosphere 61 (2005): 248-58.

13 A. Koutsospyros et al., “A Review of Tungsten: From Environmental Obscurity to Scrutiny,” Journal of Hazardous Materials 136 (2006): 1-19.

Company Overview

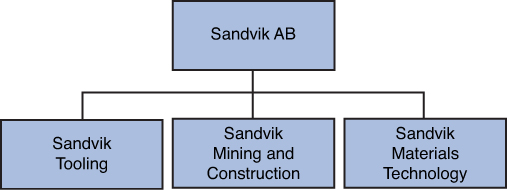

The Sandvik Group, founded in 1862, was a global high-technology engineering firm headquartered in Sandviken, Sweden. In 2008, Sandvik Group had 50,000 employees, SEK93 billion (USD13.6 billion) in sales, and a net profit of SEK10.6 billion (USD1.6 billion). Operating in 130 countries, the group was organized into the following three business areas, each a global leader in its market (Exhibit 3):

• Sandvik Tooling: Cemented carbide inserts,14 tools, and tooling systems for metal cutting, as well as blanks and components in cemented carbide.15

14 Sandvik Tooling was selling some 200 million inserts a year.

15 Sandvik Tooling also had a very strong position in tools made from high-speed steel, which was steel with certain additives that included tungsten carbide. In 1992, Sandvik Tooling acquired CTT, the world leader in high-speed steel cutting tools, a market more fragmented than cemented carbide.

• Sandvik Mining and Construction: Equipment, tools, and service for the mining and construction industries.

• Sandvik Materials Technology: Products in advanced stainless materials, special alloys, metallic and ceramic resistance materials, and process systems.

Between 1998 and 2008, Sandvik Tooling’s sales grew at an average annual rate of 8%, with an average operating margin of 20% (including some decline in 2002–03). The global economic crisis that started at the end of 2008 was very challenging for Sandvik Tooling: Sales in the first six months of 2009 were 39% lower than the same period the year before, and the company faced an operating loss of SEK196 million (USD25.1 million).16 Over the years, the business area developed a model of high consistency across the entire supply chain, from raw material to application techniques. It was convinced that applying its unique skills to all stages was the most effective way to provide its customers with continuous increases in productivity.

16 From September 2008 to June 2009, Sandvik Tooling embarked on a major cost-cutting program and reduced its work force by about 1,800.

Sandvik Tooling’s Supply Chain

Manufacturing

Production operations were based on a common raw material base, common processes, standardized equipment, and uniform standards of quality, which allowed all manufacturing units to be linked to the central warehouses through a joint control system. Beginning in the mid-1980s, all tool holder factories were progressively retooled for production as cells or miniplants. It was also decided that each major plant could supply all the products of all the different brands.

Logistics

In 2009, Sandvik Tooling served its customers from three central warehouse locations: in the Netherlands for Europe, in Kentucky for the Americas, and in Singapore for Asia. From these three warehouses the company provided 24-hour delivery of standard products to its customers all over the world. This system had been developed progressively and improved continuously since the first two central warehouses had been created to serve the European markets in the early 1980s. The low weight and high value of the products—the inserts in particular—led to extensive use of air and road transport (vans and cars).

R&D and New Product Development

Sandvik Tooling had more than 3,000 patents, and about 70% of the products sold were patent-protected. Sandvik Tooling had about 700 specialists working with research and development in metal cutting. Over the years, product development time had been significantly reduced, and 50% of the products sold had been available less than five years.

Multibranding

For many years, the company had a main brand, Coromant, and a few other brands from acquired companies. In 1992, when it acquired CTT, the world leader in high-speed steel tools, Sandvik Tooling decided to keep the different brands of CTT and expand its multibrand strategy. Two new brands were added with the acquisitions of Walter in Germany and Valenite in the United States. In 2003, multibranding became the rule, and all the different brands could use the portfolio of patents held by the business area.

Cooperation with Customers

The main customers were global automotive, aerospace, steel, energy, and general engineering firms. The strategy of Sandvik Tooling was to establish and nurture partnerships in productivity and value with its customers.17 The company had also created more than 20 training centers all over the world where customers and employees learned how to increase productivity. Moreover, the company had developed a full range of services for its customers, from data provision to the complete undertaking of selected processes. Sandvik Tooling also used to guarantee the performance of its products, typically through a reimbursement clause.

17 In the 20th century, productivity in the engineering industry had increased by a factor of about 100 on the strength of development in cemented carbide tools and machine tools. Cutting tools accounted for only 2% to 4% of total costs for finished components, but, utilized correctly, they often provided customers with savings of 10% to 30%. Market research confirmed that, when selecting a tool, customers were very concerned with productivity improvement. See for example the 2007 MAN Cutting Tools Survey (http://www.modernapplicationsnews.com/mediakit/MAN_cutting_tool_survey_2008.pdf). Important reasons for choosing a certain brand of cutting tool (as expressed by customers) were performance (59%), past experience with company (10%), customer service (7%), quality (7%), and price (6%).

Quality

All employees were responsible for the quality of their own work, and quality was defined as satisfied customers and zero defects, achieved through preventive action and continuous improvement. In 2009, all the units had obtained ISO 14001 and OHAS 18001 certification.

Organization and Culture

Organization

With the multibrand strategy, the organization was managed as a matrix: brands in one dimension, functions (R&D, product management, manufacturing, finance and business development, HR, and IT) in the other. In Sandvik, 4.4% of the people were working in R&D, 26.7% in marketing and sales, 60.0% in manufacturing, and 11.1% in IT, finance, and HR. Sandvik was paying a lot of attention to people and skills development. There was a global internal labor market with the stated goal of recruiting 90% internally (70% from within the business area and 20% from other business areas).

Culture

Sandvik was often described as the quintessential Swedish company: strong work ethic, understated, and reasonable effectiveness. In 2002, a program was instituted to strengthen the corporate culture by emphasizing Sandvik Group’s three core values: Open Mind (constant renewal, positive attitude toward change, encouragement of new ideas, freedom of action, and Sandvik’s interest always a priority), Fair Play (high ethical standards, fair trade, accuracy of records, equal opportunities, environmental responsibility), and Team Spirit (mutual trust, enthusiasm and cooperation across borders, a climate of respect, partnership with customers, and leadership).18 According to Sandvik Group’s executive management, sustainability issues were part of Sandvik’s operations. As Hallberg characterized it, “If a company wants to be aggressive in the market, it should also be proactive in sustainability issues” (Exhibit 4).

18 Values, business principles, and code of conduct were part of The Power of Sandvik, a manual describing Sandvik Tooling’s way of doing business.

Sandvik Tooling’s position as industry leader resulted directly from its process of continuous improvement. In the 2000s, the company had to deal with several issues: consolidation of the cemented carbide tools industry, integration of acquired companies, transition from high-speed tools to solid carbide tools,19 the need to increase the cemented carbide capacity, and temporary market downturns. During that period, Sandvik Tooling carried out several programs of rationalization and investment, the most notable (2001–03) resulting in the closure of 20 out of more than 40 supply units.

19 High-speed steel maintained its position in several niches.

The CRC at Sandvik Tooling

Cemented Carbide Recycling

A recycling industry existed with a well-established infrastructure of brokers and processors of tungsten scrap. Typically, one of two recycling processes was used.

Zinc process: The scrap would be sorted and cleaned under stringent quality control, then combined with zinc in a high-temperature vacuum furnace to break down the metal structure for pulverization. Yield losses were low and could be recovered.

Chemical process: In this process, tungsten, cobalt, and other components could be extracted one at a time from scrap using chemicals. This process consumed more energy than the zinc process but less than the treatment of virgin material. Because the chemical process separated all the minerals, 100% could be recovered and reused. The use of chemicals had a greater environmental impact than the zinc process, and the cost was higher (although less than the treatment of ore). Plus, building a chemical process facility required twice the initial investment needed for a zinc facility.

History

The CRC started in 1996 as a project completed by a team of managers who attended a leadership development program. Despite its sponsorship by executive management, the project met resistance, and its impact remained limited until the project was relaunched within Sandvik Tooling years later. A new working group was assembled, and Lars Hallberg was put in charge of the global organization, which was to set goals for each individual market (based on sales weight), to set prices (prices paid to the customer, prices at the consolidation point, and prices at the recycling factory), to organize promotion and market communication, and to address a few legal issues. The working group was also responsible for organizing reverse logistics outside the individual local markets, setting the environmental standards, deciding about the packaging, motivating the organization, following up, and serving as the global point of contact. For Hallberg, this was a part-time job.

In 2005, Sandvik Tooling decided to create a new zinc process recycling facility in Chiplun, India; it began operations in 2007. There were many reasons for having this plant in India: size and expected growth of the Indian and Asian markets, technical capability of Sandvik’s Indian workforce, quality consistent with the firm’s high standards, and relatively low investment cost.

External competitors offered recycling services at a national or regional level; in 2009, Sandvik Coromant was the only brand offering its customers recycling service on a global scale.

The Reverse Supply Chain

The CRC sought to collect from customers stand-alone cemented carbide inserts of any brand—even those made by competitors.20 A customer could call the local Coromant service center and request a free recycling kit, which included instructions, a recycling return form, a collection container, and a transportation container labeled for shipping. Containers came in three sizes: a 4.5 kg (10 lb.) plastic container, a 20 kg (44 lb.) wooden box, and a 230 kg (500 lb.) barrel (Figure 6-2). Once a container was full, the customer called Coromant to get a price per kilo and an authorization number for shipment.21 Two to three weeks after receipt of the material, the customer received a check.

20 Solid carbide drills and end mills shipped in separate boxes were also accepted.

21 Transport costs were generally paid by the customer.

Figure 6.2 Collection containers for carbide inserts.

To collect the inserts, Coromant had to develop a completely new reverse supply chain independent of its forward supply chain; according to Hallberg, people in the forward supply chain centers did not want to hear about reverse logistics. The recycling factory in India received material from five global consolidation points—the United States, Singapore, Germany, Brazil, and Sweden—each of which received material from concentration points or, sometimes, directly from the customer. Forward and reverse supply chains are shown in Exhibit 5. For each type of transport, minimum weights were defined: to a consolidation point, 500 kg; to the factory itself, 20 tons (a whole container). Material was transported by road and sea. Particularly in Europe, used inserts were generally considered waste, and environmental regulations required documentation of any waste transported across borders, so transporters had to be accustomed to compliance with such laws.

Different rates of accumulation resulted in many stocks located at different points in the chain.22 To catch stray tool holders or steel bars, products had to be visually inspected on intake; screening for ceramics required more thorough checks.

22 For example, a small customer might take two to three months to fill a box; a large customer might fill a barrel in six. A small concentration point might require an additional six months to accumulate the minimum quantity for transport to a consolidation point.

In-house or Outsource?

Sandvik Tooling had been using several processors—Osram in particular—to recycle new scrap for years, but Sandvik decided to build its own in-house recycling facility for several reasons. According to some, tungsten was a strategic material supply for the company, so it was important to have control over it. Others saw recycling as an important part of the Group’s sustainability approach that was going to stay: Tomorrow, everything is going to be recycled. In addition, recycling was an integral part of the development of new materials, and although the use of recycled materials made no difference in the quality of the products, it helped Sandvik learn more about the material development process. A final argument was that recycling could be run as a profitable activity. On the other hand, opponents of the in-house approach were arguing that, especially for the sales organization, the recycling process was a resource-demanding activity, not a core competency that would result in increased stocks and investment.

Environmental Impact

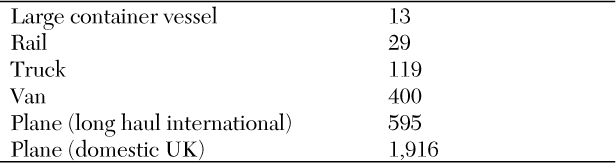

Production using recycled material consumed 75% less energy (gas, gasoil, and electricity) and reduced CO2 emissions by 40% (the latter partly due to the type of electricity available at the India plant). Transport was not taken into account, although it was clear that recycling required less of it. Exhibit 6 shows the very different CO2 emissions caused by different modes of transport. No impact assessment had yet been made for water and chemicals. Environmental impact data for Sandvik as a whole are in Exhibit 7.

Pricing of Scrap

There was no official market price for secondary tungsten products, so Coromant established a process for setting the price paid to customers. Once a quarter, headquarters in Sweden set price lists in 10 market areas.23 These price lists were set in consultation with local selling companies and factored in prices of virgin tungsten and quotes by local scrap brokers. Headquarters also fixed the price paid by the Indian recycling factory. As a result, local companies tended to break even on their recycling activities.

23 In 2008, when the prices of virgin tungsten fell rapidly, headquarters had to readjust its prices faster.

Local Sales Organizations: The U.S. Example

CRC leadership asked all local sales companies to appoint a part-time champion to promote the program, set goals, assist in price setting, and organize transport, first to the local collection point and then to a consolidation point and administration. The U.S. champion was devoting 10% to 15% of his time to the CRC. As in most markets, the recycling activity was run as a break-even business. Evolution of volumes and prices is in Exhibit 8. In the United States, postconsumer insert recycling started slowly in the late 1990s; by 2008, Coromant USA recovered about 30% of its products sold (in weight), slightly below the global target.24 When the price peaked in 2008, brokers offered scrap to Coromant USA, whose policy was to buy only from customers.

24 One of the issues in the United States was the way in which the target and the performance were calculated: The recovered amounts were compared to the current sales and not to sales corresponding to the period when the returning products were delivered (one year earlier on average).

One of the problems with the recycling business was how different it was from Coromant’s highly effective business.25 In the United States, factories used what were usually cash proceeds from selling scrap to finance Christmas parties and other social activities. Although Coromant USA mandated that payments go to a corporate account, that account was not yet integrated into its electronic routines; checks still had to be written manually. Initially, sales people and sales managers were concerned with the time this new activity required and the possibility that customers might perceive products from recycled material to be of lower quality.26 Also, the U.S. champion was having difficulties with the small box given to customers to send their inserts back: “It is not fully adapted to the U.S. market, and it results in high shipping costs.”27

25 At that time more than 85% of the order entries were electronic.

26 In the United States, people in sales were not getting any commissions from the recycling business.

27 At the end of 2008, Kennametal—Sandvik’s main U.S. competitor—seemed to be less active on the scrap market: Its website for scrap was down for several weeks.

Preparing for his meeting, Lars Hallberg had several issues on his mind. Was it wise to decouple the forward and reverse supply chains? How could the latter be improved? Was the target of 50% reclamation—including those of the competition—reasonable? How should it be measured? Hallberg knew that some competitors considered recycling a waste of time and resources and wondered if it made sense to continue with the program at all. Should recycling remain a core activity for Sandvik Tooling? Why not take advantage of a well-organized infrastructure of brokers and processors and outsource it?

Exhibit 1A. Sandvik Coromant Recycling Concept

Market Prices for Tungsten and Cobalt

Tungsten Prices (USD), 1994–2008

Note: Prices are for concentrate in U.S. dollars per ton of WO3 (tungsten oxide powder), each ton containing 7.93 kg. of tungsten. Data source: U.S. Geological Survey website, http://minerals.er.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/tungsten/ (accessed July 27, 2011).

Note: Prices are average annual U.S. spot prices for cathode (minimum of 99.8% of cobalt) and are expressed in U.S. dollars per pound. Data source: U.S. Geological Survey website, http://minerals.er.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/cobalt/ (accessed July 27, 2011).

Exhibit 2A. Sandvik Coromant Recycling Concept

Recyclability of Tungsten and Cobalt in the United States28

Data source: U.S. Geological Survey website, http://minerals.er.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity (accessed July 27, 2011).

28 New scrap was defined as scrap produced during the manufacture of metals and articles for both intermediate and ultimate consumption, including all defective finished or semifinished articles that must be reworked. Old scrap was postconsumer scrap.

Data source: International Tungsten Industry Association. This view does not include changes in strategic stocks.

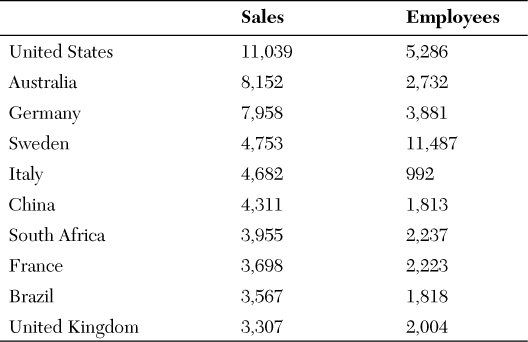

Sales, Operating Profit and Numbers of Employees by Business Area, 2008 (sales in millions of Swedish kronor)

Sandvik Group Sales and Number of Employees in 10 Largest Markets, 2008 (sales in millions of Swedish kronor)

Data source: Sandvik 2008 annual report.

Exhibit 4 Sandvik Coromant Recycling Concept

Sandvik Group’s Sustainability Policy

In 2002, the Group Executive Management established the target that all major (more than 20 people) units shall be certified in accordance with ISO 14001 international standards for environmental management systems before the end of 2004. At year-end 2008, 82% of the units were certified, and most of the units not yet certified were recent acquisitions. In 2006, the Group Executive Management decided that all units should be certified in accordance with the OHAS 18001 international standard for health and safety management systems or the equivalent. At year-end 2008, 89% of the units were certified. New environmental and social goals were set in 2006 and then revised in 2008:

Vision

Sandvik’s vision is to be recognized by its stakeholders as a company with excellent environment, health and safety performance. To achieve this Sandvik must ensure that:

• Its sites minimize any potential environmental impacts such as energy use and input materials in the most efficient way.

• Its sites minimize any risks to health, safety, and well-being of employees.

• Its products and technical solutions provide long service lifetimes and better resource utilization.

• Its products and technical solutions have minimal environmental impact when used by a customer.

• Its products and technical solutions are fully recyclable.

Policy

In December 2008, Group Executive Management established a new environment, health and safety policy for all business areas:

• Environmental, health and safety issues are integral parts of Sandvik’s total operations, and the company achieves continual improvement in these areas through management by objectives. Sandvik believes that the greatest effect is achieved through preventive actions.

• The company follows an approach that results in long-term sustainable development in its operations. Consequently, Sandvik strives for high efficiency in the use of energy and natural resources, promotes systems for recycling and recovery of materials, and works to prevent pollution and any work-related illness and injury.

• Sandvik strives to provide a healthy and safe work environment that stimulates employees to perform effectively, to assume responsibility, and to continue to develop towards their personal and professional goals.

• Sandvik complies with or exceeds applicable environmental, health and safety, legal, and other requirements. The company believes that common and effective environmental, health and safety requirements and standards should be established at an international level.

Goals for Sustainability Programs

Sandvik’s Group Executive Management set new sustainability objectives and targets in November 2008 (see Exhibit 7 for environmental impact data). Here are the environmental objectives and targets that were set:

Group’s environmental objectives:

• More efficient use of energy and input materials

• Reduced emissions to air and water

• Increased recovery of materials and by-products29

29 Sandvik Tooling recycled 40% of all sold and worn-out cemented carbide cutting tools in a factory opened in Chiplun, India in 2006. The goal was 50%.

• Reduced environmental impact from the use of hazardous chemicals30

30 Hazardous chemicals were used only to a limited extent and were subsequently handled in accordance with environmentally safe methods.

• Increased number of products that support sustainability principles

Group’s environmental targets:

• Reduce the use of energy in relation to sales volume by 10% before year-end 2012 (base 2008)

• Reduce consumption of fresh water in relation to sales volume by 10% before year-end 2012 (base 2008)

• Commence reporting of waster discharged from sites before year-end 2009

• Replace all chlorinated solvents such as dichloromethane, tetrachloroethene, tetrachloromethane, trichloroethane and trichloroethene with other solvents or techniques by the end of 2010

• Reduce CO2 emissions from internal use of fossil fuels and electricity by 10% in relation to sales volume before year-end 2012 (base 2008)

• Commence reporting of carbon dioxide emission arising from transportation before year-end 2009

• All major production, service, and distribution units shall be certified in accordance with ISO 14001 within two years of acquisition or establishment

Source: Company documents.

Data source: Company documents, case writers’ estimates.

Exhibit 6 Sandvik Coromant Recycling Concept

CO2 Emissions by Mode of Transport (in grams per kilometer)

Note: In its 2009 sustainability report, UPS (UPS Airlines global operations) reported emissions of 340 g of CO2 per ton transported, to be reduced to 302 in 2020.

Data source: UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), http://www.defra.gov.uk/environment/business/reporting/pdf/20090928-guidelines-ghg-conversion-factors.pdf; UPS 2009 Sustainability Report, http://www.responsibility.ups.com/community/Static%20Files/sustainability/UPS_V27_0718_300dpi_rgb.pdf. Additional data can be obtained from the site of the Swedish-based Network for Transport and Environment (NTM), http://www.ntmcalc.se/index.html.

Data source: Company documents.

31 Sandvik’s sales growth in 2007, 2008, and 2009 was 14.1%, 19.4%, and 7.3%, respectively.

32 For tungsten, Sandvik used 60% of recycled material (2009 Sustainability Report).

33 In relation to sales volume and from a base of 100 in 2004, energy consumption was 86 in 2008.

34 Impact of transport was not reported.

35 In relation to sales volume and from a base of 100 in 2004, CO2 emissions were 96 in 2008.

Exhibit 8 Sandvik Coromant Recycling Concept

Cemented Carbide Prices and Quantity Collected in the United States

Price per Kilogram of Cemented Carbide, 2006–09 (in U.S. dollars)

Tons of Cemented Carbide Collected, 2005–08

Data source: Company documents.